ADA1-Driven Metabolic Refueling Enhances CAR T Cell Therapy for Solid Tumors

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Current Perspectives and Recent Advances in CAR T Cell Therapy for Solid Tumors

2.1. Multi-Targeted CAR Designs

2.2. Overcoming Immune Suppression

2.3. Strategies to Address T Cell Exhaustion and Senescence

2.4. Metabolic Reprogramming Approaches

3. The Tumor Microenvironment, Metabolic Barriers, and T Cell States

3.1. Hostile Features of the Solid Tumor Microenvironment

3.2. Metabolic Competition and Suppression by Tumor Cells

3.3. Adenosine (ADO) as a Dominant Immunosuppressive Metabolite

3.4. T Cell Metabolic States and Vulnerabilities in the TME (Table 1)

- •

- •

- •

- Memory T cells, including central (T_CM) and effector (T_EM) subsets, possess enhanced mitochondrial mass and metabolic plasticity, allowing more effective adaptation in hostile environments. Nevertheless, they remain susceptible to inhibition by adenosine, lactic acid, and nutrient deprivation [55,56,57].

- •

- Exhausted T cells, which accumulate in tumors after chronic antigen exposure and ongoing metabolic stress, are characterized by impaired mitochondrial function, low energy reserves, diminished glycolytic and oxidative capacity, and sustained expression of inhibitory receptors such as PD-1, LAG-3, and TIM-3. They show reduced proliferation, cytokine secretion, and cytolytic activity, further reinforced by high adenosine via the CD39/CD73 axis [58,59,60]. This ultimately promotes apoptosis and loss of potentially tumor-reactive clones.

| T Cell Subset | Dominant Metabolic Program | Metabolic Features | Functional Role in Immunity | Key Surface Receptors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naïve T Cell [15,54] | OXPHOS, fatty acid oxidation (FAO) | Low nutrient uptake, energy-efficient, quiescent, high AMPK and low mTOR activity | Long-term surveillance, maintenance of diversity | CD45RA, CD62L, CCR7, TCR (low activation) |

| Activated Effector T Cell [15,54] | Aerobic glycolysis, increased glutaminolysis | High nutrient (glucose, glutamine) uptake, strong anabolic drive, high mTOR activity, rapid biosynthesis | Proliferation, cytokine secretion, cancer cell killing | CD25 (IL-2Rα), CD28, GLUT1, CD98, CD69, TCR (high activation) |

| Central Memory T Cell [55,56,57] | OXPHOS, FAO, preserved glycolytic capacity | Mitochondrial remodeling, increased spare respiratory capacity, energy flexibility | Long-term survival, rapid reactivation, migration | CD45RO, CD62L, CCR7, IL-7Rα (CD127), TCR |

| Effector Memory T Cell [55,56,57] | Mixed OXPHOS and glycolysis | Intermediate metabolic activity, poised for effector function | Immediate protection at peripheral tissues | CD45RO, lower CD62L, CXCR3, TCR |

| Exhausted/Dysfunctional T Cell [58,59,60] | Impaired glycolysis and OXPHOS, ADO accumulation, disrupted mTOR signaling | Mitochondrial fragmentation, low ATP production, bioenergetic crisis, upregulation of inhibitory pathways | Dysfunction, poor proliferation, loss of cytotoxicity | PD-1, TIM-3, LAG-3, CTLA-4, A2A adenosine receptor |

4. Extracellular Adenosine: Production, Accumulation, and Immunosuppressive Functions

4.1. Mechanisms of Adenosine Generation: The CD39/CD73 Axis

4.2. Immunosuppressive Signaling via A2A and A2B Receptors on T Cells

- •

- Inhibits proximal TCR signaling (by interference with protein kinase C, Zap70/Zeta-chain (TCR)-associated protein kinase 70, and downstream NFAT and NF-κB activation);

- •

- Suppresses cell proliferation and blockades cell cycle progression of T cells;

- •

- Reduces cytotoxic function by lowering the expression of perforin and granzymes and weakening immune synapse formation;

- •

- Blocks cytokine gene expression and secretion (notably IFN-γ/interferon gamma, IL-2, TNF-α/tumor necrosis factor alpha) even in already activated cells, thereby blunting further immune recruitment and amplification;

- •

- Promotes T cell exhaustion by enhancing the expression of co-inhibitory receptors (PD-1, TIM-3, LAG-3) and reducing metabolic fitness, ultimately predisposing cells to apoptosis.

4.3. Adenosine as a Metabolic Modulator Supporting Cancer Cell Survival and Progression

- •

- •

- Induction of angiogenesis: A2B receptor signaling upregulates the expression of VEGF and other pro-angiogenic factors, enhancing the blood supply to the tumor [78].

- •

- •

- Resistance to therapy: Adenosine-rich environments have been linked to resistance to immune checkpoint blockade, chemotherapy, and radiation, largely due to protected “immune-privileged” metabolic niches that shield cancer cells from immune elimination [83].

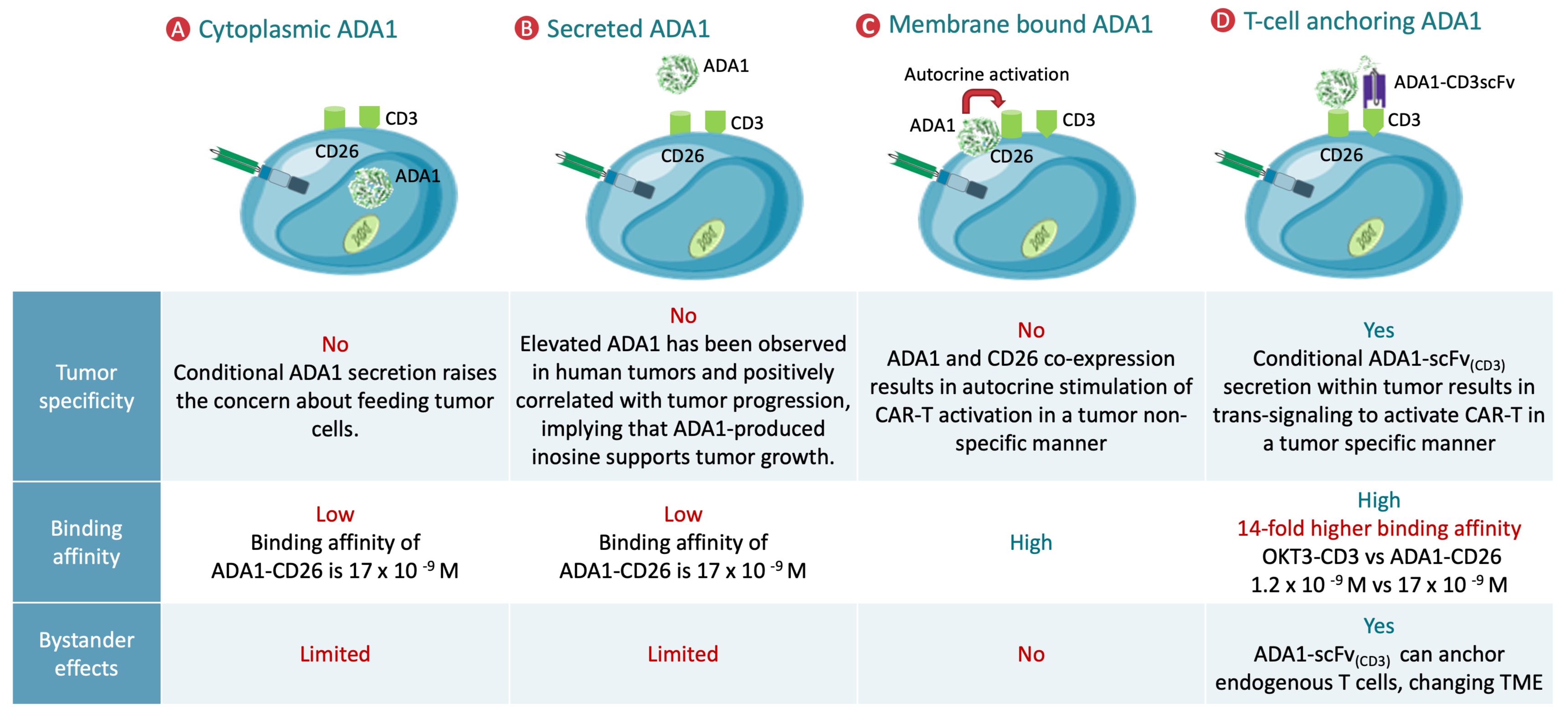

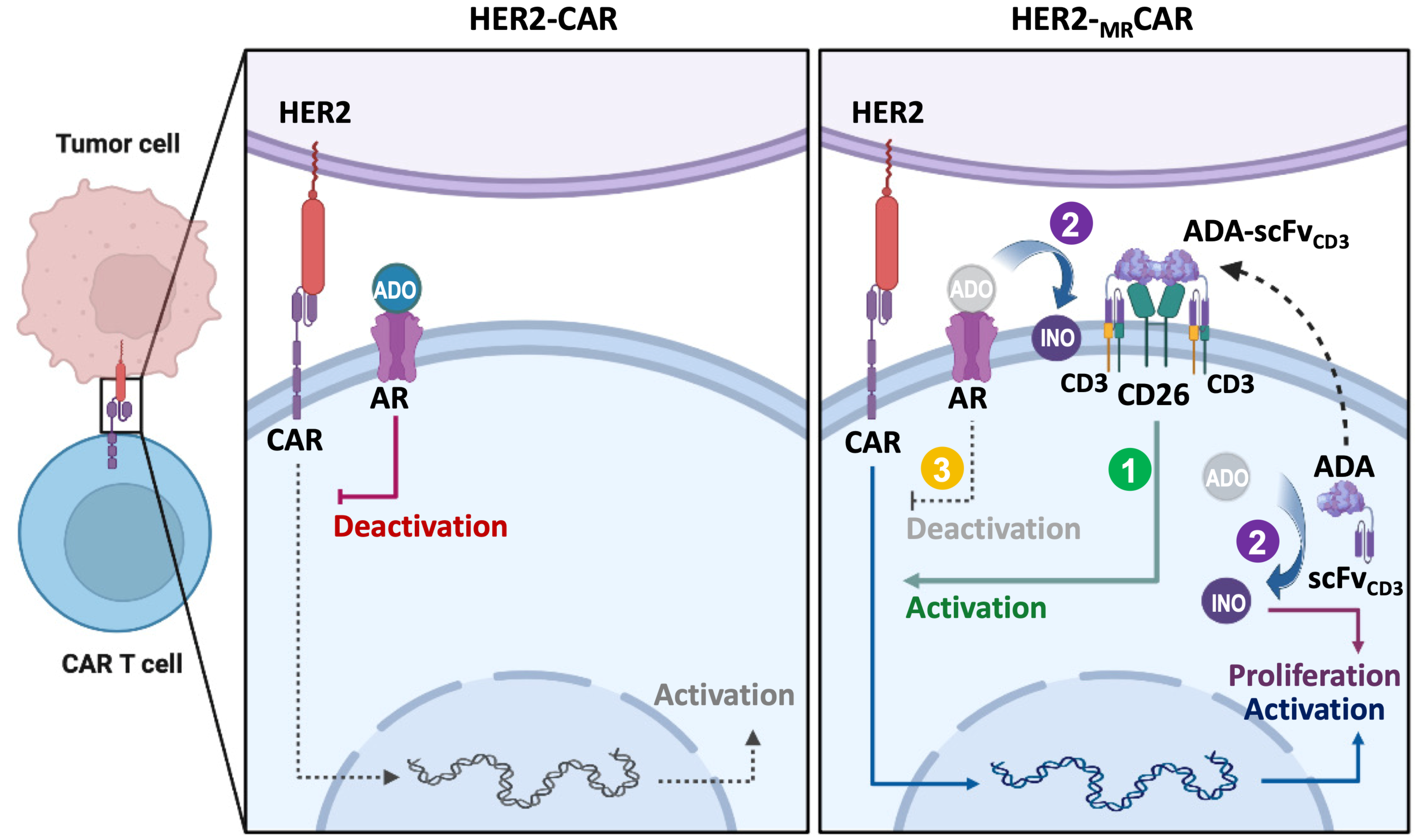

5. ADA1-Mediated Metabolic Refueling in CAR T Cells

5.1. Mechanistic Basis of ADA1 Function in T Cells

5.2. Synergistic Role of CD26 and ADA1 in Metabolic Reprogramming

5.3. Impact of ADA1-Mediated Refueling on CAR T Cell Phenotype and Function

5.4. Preclinical Models and Translational Relevance

6. Challenges, Controversies, and Future Directions in ADA1-Mediated CAR T Cell Metabolic Reprogramming

6.1. Technical, Biological, and Translational Challenges

6.2. Controversies and Knowledge Gaps in Metabolite Manipulation

6.3. Comparative Perspectives and Need for Integrated Strategies

6.4. Clinical Translation and Regulatory Considerations

6.5. Directions for Future Research and Reconceptualization

- •

- Mechanistic Elucidation: How does ADA1 activity reshape metabolic pathways, signaling networks, and epigenetic landscapes within CAR T cells? What are the regulatory circuits that link inosine utilization to memory formation and exhaustion resistance?

- •

- Tumor Heterogeneity and Resistance: How do distinct tumor types, metabolic niches, and adaptive responses influence ADA1/CAR T cell efficacy and long-term durability? Can signatures of TME composition be harnessed for personalized therapy?

- •

- Safety Optimization: What are the risks of inadvertent tumor support, autoimmune responses, or metabolic imbalances arising from ADA1 activity? How can spatially and temporally controlled expression systems, such as inducible or tissue-specific promoters, mitigate these risks?

- •

- Clinical Integration: What are the best practices for combining ADA1-engineered CAR T cells with other immunotherapies, metabolic inhibitors, or emerging CART platforms? How can clinical trials be designed to capture the full impact of these multifaceted interventions?

- •

- Broader Applicability: Can ADA1-mediated refueling be extended to other cell therapies, such as TCR-T cells, NK cells, or macrophage engineering? What are the implications for other metabolite-mediated immunosuppressive axes in cancer and beyond?

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maude, S.L.; Frey, N.; Shaw, P.A.; Aplenc, R.; Barrett, D.M.; Bunin, N.J.; Chew, A.; Gonzalez, V.E.; Zheng, Z.; Lacey, S.F.; et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 1507–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maude, S.L.; Laetsch, T.W.; Buechner, J.; Rives, S.; Boyer, M.; Bittencourt, H.; Bader, P.; Verneris, M.R.; Stefanski, H.E.; Myers, G.D.; et al. Tisagenlecleucel in Children and Young Adults with B-Cell Lymphoblastic Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintás-Cardama, A. Anti-BCMA CAR T-Cell Therapy in Multiple Myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raje, N.; Berdeja, J.; Lin, Y.; Siegel, D.; Jagannath, S.; Madduri, D.; Liedtke, M.; Rosenblatt, J.; Maus, M.V.; Turka, A.; et al. Anti-BCMA CAR T-Cell Therapy bb2121 in Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1726–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davila, M.L.; Riviere, I.; Wang, X.; Bartido, S.; Park, J.; Curran, K.; Chung, S.S.; Stefanski, J.; Borquez-Ojeda, O.; Olszewska, M.; et al. Efficacy and toxicity management of 19-28z CAR T cell therapy in B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 224ra225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.W.; Kochenderfer, J.N.; Stetler-Stevenson, M.; Cui, Y.K.; Delbrook, C.; Feldman, S.A.; Fry, T.J.; Orentas, R.; Sabatino, M.; Shah, N.N.; et al. T cells expressing CD19 chimeric antigen receptors for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children and young adults: A phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet 2015, 385, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turtle, C.J.; Hanafi, L.A.; Berger, C.; Gooley, T.A.; Cherian, S.; Hudecek, M.; Sommermeyer, D.; Melville, K.; Pender, B.; Budiarto, T.M.; et al. CD19 CAR-T cells of defined CD4+:CD8+ composition in adult B cell ALL patients. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 2123–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turtle, C.J.; Hanafi, L.A.; Berger, C.; Hudecek, M.; Pender, B.; Robinson, E.; Hawkins, R.; Chaney, C.; Cherian, S.; Chen, X.; et al. Immunotherapy of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma with a defined ratio of CD8+ and CD4+ CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8, 355ra116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, C.U.; Savoldo, B.; Dotti, G.; Pule, M.; Yvon, E.; Myers, G.D.; Rossig, C.; Russell, H.V.; Diouf, O.; Liu, E.; et al. Antitumor activity and long-term fate of chimeric antigen receptor-positive T cells in patients with neuroblastoma. Blood 2011, 118, 6050–6056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.R.; Digiusto, D.L.; Slovak, M.; Wright, C.; Naranjo, A.; Wagner, J.; Meechoovet, H.B.; Bautista, C.; Chang, W.C.; Ostberg, J.R.; et al. Adoptive transfer of chimeric antigen receptor re-directed cytolytic T lymphocyte clones in patients with neuroblastoma. Mol. Ther. 2007, 15, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, B.; Shi, D.; Gao, H.; Qi, X.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chi, J.; Ruan, H.; Wang, H.; Ru, Q.C.; et al. A phase I study of anti-GPC3 chimeric antigen receptor modified T cells (GPC3 CAR-T) in Chinese patients with refractory or relapsed GPC3+ hepatocellular carcinoma (r/r GPC3+ HCC). J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhang, H.; Miao, C. Metabolic reprogram and T cell differentiation in inflammation: Current evidence and future perspectives. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renauer, P.; Park, J.J.; Bai, M.; Acosta, A.; Lee, W.H.; Lin, G.H.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, X.; Wang, G.; Errami, Y.; et al. Immunogenetic Metabolomics Reveals Key Enzymes That Modulate CAR T-cell Metabolism and Function. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2023, 11, 1068–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Gnanaprakasam, J.N.R.; Sherman, J.; Wang, R. A Metabolism Toolbox for CAR T Therapy. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Liu, G.; Wang, R. The Intercellular Metabolic Interplay between Tumor and Immune Cells. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Zhao, Y.; Han, Y.; Li, M.; Wang, G. Targeting glutamine metabolism crosstalk with tumor immune response. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2025, 1880, 189257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petiti, J.; Arpinati, L.; Menga, A.; Carra, G. The influence of fatty acid metabolism on T cell function in lung cancer. FEBS J. 2025, 292, 3596–3615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Sarkar, A.; Song, K.; Michael, S.; Hook, M.; Wang, R.; Heczey, A.; Song, X. Selective refueling of CAR T cells using ADA1 and CD26 boosts antitumor immunity. Cell Rep. Med. 2024, 5, 101530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klysz, D.D.; Fowler, C.; Malipatlolla, M.; Stuani, L.; Freitas, K.A.; Chen, Y.; Meier, S.; Daniel, B.; Sandor, K.; Xu, P.; et al. Inosine induces stemness features in CAR-T cells and enhances potency. Cancer Cell 2024, 42, 266–282.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Sarkar, A.; Song, X. Protocol for preparing metabolically reprogrammed human CAR T cells and evaluating their in vitro effects. STAR Protoc. 2024, 5, 103333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suarez, V.J.; Martin-Rodriguez, A.; Redondo-Florez, L.; Ruisoto, P.; Navarro-Jimenez, E.; Ramos-Campo, D.J.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Metabolic Health, Mitochondrial Fitness, Physical Activity, and Cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katopodi, T.; Petanidis, S.; Anestakis, D.; Charalampidis, C.; Chatziprodromidou, I.; Floros, G.; Eskitzis, P.; Zarogoulidis, P.; Koulouris, C.; Sevva, C.; et al. Tumor cell metabolic reprogramming and hypoxic immunosuppression: Driving carcinogenesis to metastatic colonization. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1325360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanjireddy, P.M.; Olejniczak, S.H.; Buxbaum, N.P. Targeting of chimeric antigen receptor T cell metabolism to improve therapeutic outcomes. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1121565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Gnanaprakasam, J.N.R.; Chen, X.; Kang, S.; Xu, X.; Sun, H.; Liu, L.; Rodgers, H.; Miller, E.; Cassel, T.A.; et al. Inosine is an alternative carbon source for CD8+-T-cell function under glucose restriction. Nat. Metab. 2020, 2, 635–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shifrut, E.; Carnevale, J.; Tobin, V.; Roth, T.L.; Woo, J.M.; Bui, C.T.; Li, P.J.; Diolaiti, M.E.; Ashworth, A.; Marson, A. Genome-wide CRISPR Screens in Primary Human T Cells Reveal Key Regulators of Immune Function. Cell 2018, 175, 1958–1971.e1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, Y.; Dunn, Z.S.; Chen, X.; MacMullan, M.; Cinay, G.; Wang, H.Y.; Liu, J.; Hu, F.; Wang, P. Adenosine Deaminase 1 Overexpression Enhances the Antitumor Efficacy of Chimeric Antigen Receptor-Engineered T Cells. Hum. Gene Ther. 2022, 33, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, E.F.; Felip, E.; Uprety, D.; Nagasaka, M.; Nakagawa, K.; Paz-Ares Rodriguez, L.; Pacheco, J.M.; Li, B.T.; Planchard, D.; Baik, C.; et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (DESTINY-Lung01): Primary results of the HER2-overexpressing cohorts from a single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2024, 25, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Liu, H.; Zhang, D.; Ma, Y.; Zhu, B. Metabolic plasticity and regulation of T cell exhaustion. Immunology 2022, 167, 482–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majzner, R.G.; Mackall, C.L. Tumor Antigen Escape from CAR T-cell Therapy. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 1219–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Benito, D.; Birocchi, F.; Park, S.; Ho, C.E.; Armstrong, A.; Parker, A.L.; Bouffard, A.A.; Frank, J.A.; Kim, E.; Kienka, T.; et al. Tandem CAR-T cells targeting mesothelin and MUC16 overcome tumor heterogeneity by targeting one antigen at a time. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e012822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, F.; Zheng, M.; Ding, Y.; Xiong, F.; Liu, X.; Zhou, X.; Yan, Z.; Luo, J. Tandem Dual CAR-T Cells Targeting HER2 and Mesothelin Enhance anti-Tumor Effects in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Investig. 2025, 43, 594–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Jin, X.; Wang, L. Universal CAR cell therapy: Challenges and expanding applications. Transl. Oncol. 2025, 51, 102147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Ni, Z.; Zhang, R. Universal CAR-T Cell Therapy for Cancer Treatment: Advances and Challenges. Oncol. Res. 2025, 33, 3347–3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wu, H.; Sun, Z.; Cui, Y.; Liu, N.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shi, J.; Zhang, T. shRNA-based PD-1 suppression preserves memory phenotype and function of CD19-targeted CAR-T cell. Transl. Cancer Res. 2025, 14, 6454–6468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Fu, Y.X. Inactivation of TGF-beta signaling in CAR-T cells. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2024, 21, 309–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaniya, A.; Khuisangeam, N.; Tawinwung, S.; Suppipat, K.; Hirankarn, N. A Bidirectional EF1 Promoter System for Armoring CD19 CAR-T Cells with Secreted Anti-PD1 Antibodies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tulsian, K.; Thakker, D.; Vyas, V.K. Overcoming chimeric antigen receptor-T (CAR-T) resistance with checkpoint inhibitors: Existing methods, challenges, clinical success, and future prospects: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 306, 141364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffin, D.; Ghatwai, N.; Montalbano, A.; Rathi, P.; Courtney, A.N.; Arnett, A.B.; Fleurence, J.; Sweidan, R.; Wang, T.; Zhang, H.; et al. Interleukin-15-armoured GPC3 CAR T cells for patients with solid cancers. Nature 2025, 637, 940–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- June, C.H.; Sadelain, M. Chimeric Antigen Receptor Therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, C.R.F.; Corveloni, A.C.; Caruso, S.R.; Macêdo, N.A.; Brussolo, N.M.; Haddad, F.; Fernandes, T.R.; de Andrade, P.V.; Orellana, M.D.; Guerino-Cunha, R.L. Cytokines as an important player in the context of CAR-T cell therapy for cancer: Their role in tumor immunomodulation, manufacture, and clinical implications. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 947648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinkove, R.; George, P.; Dasyam, N.; McLellan, A.D. Selecting costimulatory domains for chimeric antigen receptors: Functional and clinical considerations. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 2019, 8, e1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.; Chen, J.; Gonzalez-Avalos, E.; Samaniego-Castruita, D.; Das, A.; Wang, Y.H.; Lopez-Moyado, I.F.; Georges, R.O.; Zhang, W.; Onodera, A.; et al. TOX and TOX2 transcription factors cooperate with NR4A transcription factors to impose CD8(+) T cell exhaustion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 12410–12415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.; Gonzalez-Avalos, E.; Zhang, W.; Ramchandani, P.; Yang, C.; Lio, C.J.; Rao, A.; Hogan, P.G. BATF and IRF4 cooperate to counter exhaustion in tumor-infiltrating CAR T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2021, 22, 983–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Heiden, M.G.; Cantley, L.C.; Thompson, C.B. Understanding the Warburg effect: The metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science 2009, 324, 1029–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotgia, F.; Martinez-Outschoorn, U.E.; Pavlides, S.; Howell, A.; Pestell, R.G.; Lisanti, M.P. Understanding the Warburg effect and the prognostic value of stromal caveolin-1 as a marker of a lethal tumor microenvironment. Breast Cancer Res. 2011, 13, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mediavilla-Varela, M.; Luddy, K.; Noyes, D.; Khalil, F.K.; Neuger, A.M.; Soliman, H.; Antonia, S.J. Antagonism of adenosine A2A receptor expressed by lung adenocarcinoma tumor cells and cancer associated fibroblasts inhibits their growth. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2013, 14, 860–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Chao, M.; Wu, H. Central role of lactate and proton in cancer cell resistance to glucose deprivation and its clinical translation. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2017, 2, 16047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghashghaeinia, M.; Köberle, M.; Mrowietz, U.; Bernhardt, I. Proliferating tumor cells mimick glucose metabolism of mature human erythrocytes. Cell Cycle 2019, 18, 1316–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolff, M.; Rauschner, M.; Reime, S.; Riemann, A.; Thews, O. Role of the mTOR Signalling Pathway During Extracellular Acidosis in Tumour Cells. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2022, 1395, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, H. Extracellular metabolism of ATP and other nucleotides. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2000, 362, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deussen, A.; Stappert, M.; Schäfer, S.; Kelm, M. Quantification of extracellular and intracellular adenosine production: Understanding the transmembranous concentration gradient. Circulation 1999, 99, 2041–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrei, C.; Dazzi, C.; Lotti, L.; Torrisi, M.R.; Chimini, G.; Rubartelli, A. The secretory route of the leaderless protein interleukin 1beta involves exocytosis of endolysosome-related vesicles. Mol. Biol. Cell 1999, 10, 1463–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, J.L. PD-1 signaling in primary T cells. Immunol. Rev. 2009, 229, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buck, M.D.; O’Sullivan, D.; Klein Geltink, R.I.; Curtis, J.D.; Chang, C.H.; Sanin, D.E.; Qiu, J.; Kretz, O.; Braas, D.; van der Windt, G.J.; et al. Mitochondrial Dynamics Controls T Cell Fate through Metabolic Programming. Cell 2016, 166, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macallan, D.C.; Borghans, J.A.; Asquith, B. Human T Cell Memory: A Dynamic View. Vaccines 2017, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattinoni, L.; Speiser, D.E.; Lichterfeld, M.; Bonini, C. T memory stem cells in health and disease. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.R.; Imrichova, H.; Wang, H.; Chao, T.; Xiao, Z.; Gao, M.; Rincon-Restrepo, M.; Franco, F.; Genolet, R.; Cheng, W.C.; et al. Disturbed mitochondrial dynamics in CD8. Nat. Immunol. 2020, 21, 1540–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardhana, S.A.; Hwee, M.A.; Berisa, M.; Wells, D.K.; Yost, K.E.; King, B.; Smith, M.; Herrera, P.S.; Chang, H.Y.; Satpathy, A.T.; et al. Impaired mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation limits the self-renewal of T cells exposed to persistent antigen. Nat. Immunol. 2020, 21, 1022–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, M.; Kondo, T.; Tomisato, W.; Ito, M.; Shichino, S.; Srirat, T.; Mise-Omata, S.; Nakagawara, K.; Yoshimura, A. Rejuvenating Effector/Exhausted CAR T Cells to Stem Cell Memory-Like CAR T Cells By Resting Them in the Presence of CXCL12 and the NOTCH Ligand. Cancer Res. Commun. 2021, 1, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhulai, G.; Oleinik, E.; Shibaev, M.; Ignatev, K. Adenosine-Metabolizing Enzymes, Adenosine Kinase and Adenosine Deaminase, in Cancer. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Alabdullah, M.; Mahnke, K. Adenosine, bridging chronic inflammation and tumor growth. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1258637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandapathil, M.; Hilldorfer, B.; Szczepanski, M.J.; Czystowska, M.; Szajnik, M.; Ren, J.; Lang, S.; Jackson, E.K.; Gorelik, E.; Whiteside, T.L. Generation and accumulation of immunosuppressive adenosine by human CD4+CD25highFOXP3+ regulatory T cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 7176–7186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horenstein, A.L.; Chillemi, A.; Zaccarello, G.; Bruzzone, S.; Quarona, V.; Zito, A.; Serra, S.; Malavasi, F. A CD38/CD203a/CD73 ectoenzymatic pathway independent of CD39 drives a novel adenosinergic loop in human T lymphocytes. Oncoimmunology 2013, 2, e26246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morello, S.; Pinto, A.; Blandizzi, C.; Antonioli, L. Myeloid cells in the tumor microenvironment: Role of adenosine. Oncoimmunology 2016, 5, e1108515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, S.; Mondal, A.; Sarkar, I.; Akram Ddoza Hazari, M.W.; Banerjee, I.; Ghosh, S.; Roy, H.; Banerjee, A.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Aich, S.; et al. The hypoxia-induced chromatin reader ZMYND8 drives HIF-dependent metabolic rewiring in breast cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 2025, 301, 110680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Gong, S.; Liao, B.; Liu, J.; Zhao, L.; Wu, N. HIF-1alpha and HIF-2alpha: Synergistic regulation of glioblastoma malignant progression during hypoxia and apparent chemosensitization in response to hyperbaric oxygen. Cancer Cell Int. 2025, 25, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McColl, S.R.; St-Onge, M.; Dussault, A.A.; Laflamme, C.; Bouchard, L.; Boulanger, J.; Pouliot, M. Immunomodulatory impact of the A2A adenosine receptor on the profile of chemokines produced by neutrophils. FASEB J. 2006, 20, 187–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cekic, C.; Day, Y.J.; Sag, D.; Linden, J. Myeloid expression of adenosine A2A receptor suppresses T and NK cell responses in the solid tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 7250–7259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Yoshimura, K.; Kurabe, N.; Kahyo, T.; Kawase, A.; Tanahashi, M.; Ogawa, H.; Inui, N.; Funai, K.; Shinmura, K.; et al. Prognostic impact of CD73 and A2A adenosine receptor expression in non-small-cell lung cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 8738–8751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.; Ngiow, S.F.; Gao, Y.; Patch, A.M.; Barkauskas, D.S.; Messaoudene, M.; Lin, G.; Coudert, J.D.; Stannard, K.A.; Zitvogel, L.; et al. A2AR Adenosine Signaling Suppresses Natural Killer Cell Maturation in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 1003–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah-Mehrjardi, K.; Mirzaei, H.R.; Masoumi, E.; Jafarzadeh, L.; Rostamian, H.; Khakpoor-Koosheh, M.; Alishah, K.; Noorbakhsh, F.; Hadjati, J. Pharmacological targeting of immune checkpoint A2aR improves function of anti-CD19 CAR T cells in vitro. Immunol. Lett. 2020, 223, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Akdemir, I.; Fan, J.; Linden, J.; Zhang, B.; Cekic, C. The Expression of Adenosine A2B Receptor on Antigen-Presenting Cells Suppresses CD8. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2020, 8, 1064–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, H.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, D.C.; Ko, Y.S.; Lee, G.W.; Kim, H.J. Increased Extracellular Adenosine in Radiotherapy-Resistant Breast Cancer Cells Enhances Tumor Progression through A2AR-Akt-beta-Catenin Signaling. Cancers 2021, 13, 2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohair, B.; Chraa, D.; Rezouki, I.; Benthami, H.; Razzouki, I.; Elkarroumi, M.; Olive, D.; Karkouri, M.; Badou, A. The immune checkpoint adenosine 2A receptor is associated with aggressive clinical outcomes and reflects an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in human breast cancer. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1201632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morello, S.; Miele, L. Targeting the adenosine A2b receptor in the tumor microenvironment overcomes local immunosuppression by myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Oncoimmunology 2014, 3, e27989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, J.; Wei, G.; Liu, J.; Yang, F.; Sun, R.; Lu, H. Chemotherapy-induced adenosine A2B receptor expression mediates epigenetic regulation of pluripotency factors and promotes breast cancer stemness. Theranostics 2022, 12, 2598–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrentino, C.; Miele, L.; Porta, A.; Pinto, A.; Morello, S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells contribute to A2B adenosine receptor-induced VEGF production and angiogenesis in a mouse melanoma model. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 27478–27489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasiukov, G.; Menshikh, A.; Owens, P.; Novitskaya, T.; Hurley, P.; Blackwell, T.; Feoktistov, I.; Novitskiy, S.V. Adenosine/TGFβ axis in regulation of mammary fibroblast functions. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, J.V.; Suman, S.; Goruganthu, M.U.L.; Tchekneva, E.E.; Guan, S.; Arasada, R.R.; Antonucci, A.; Piao, L.; Ilgisonis, I.; Bobko, A.A.; et al. Improving combination therapies: Targeting A2B adenosine receptor to modulate metabolic tumor microenvironment and immunosuppression. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2023, 115, 1404–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Navio, J.M.; Casanova, V.; Pacheco, R.; Naval-Macabuhay, I.; Climent, N.; Garcia, F.; Gatell, J.M.; Mallol, J.; Gallart, T.; Lluis, C.; et al. Adenosine deaminase potentiates the generation of effector, memory, and regulatory CD4+ T cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2011, 89, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, N.; Guan, L.; Shao, C.; Lin, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, Y. High Expression of TGF-β1 Contributes to Hepatocellular Carcinoma Prognosis. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 861601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigano, S.; Alatzoglou, D.; Irving, M.; Ménétrier-Caux, C.; Caux, C.; Romero, P.; Coukos, G. Targeting Adenosine in Cancer Immunotherapy to Enhance T-Cell Function. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, M.; Huguet, J.; Centelles, J.J.; Franco, R. Expression of ecto-adenosine deaminase and CD26 in human T cells triggered by the TCR-CD3 complex. Possible role of adenosine deaminase as costimulatory molecule. J. Immunol. 1995, 155, 4630–4643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaei, M.; Karami-Tehrani, F.; Salami, S.; Atri, M. Adenosine deaminase activity in the serum and malignant tumors of breast cancer: The assessment of isoenzyme ADA1 and ADA2 activities. Clin. Biochem. 2005, 38, 887–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, G.W.; Lee, D.D.; Ross, W.G.; DiVietro, J.A.; Lappas, C.M.; Lawrence, M.B.; Linden, J. Activation of A2A adenosine receptors inhibits expression of alpha 4/beta 1 integrin (very late antigen-4) on stimulated human neutrophils. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2004, 75, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, H.J.; Liu, Z.C.; Wang, D.S.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Y.L.; Dou, K.F. Adenosine A(2b) receptor is highly expressed in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol. Res. 2006, 36, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehuda, S.; Stemmer, S.; Castel, D. A3 adenosine receptor is highly expressed in hepatocellular carcinoma: A new therapeutic target. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 13164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, M.; Benmebarek, M.R.; Briukhovetska, D.; Markl, F.; Dorr, J.; Cadilha, B.L.; Jobst, J.; Stock, S.; Andreu-Sanz, D.; Lorenzini, T.; et al. Impact of the selective A2(A)R and A2(B)R dual antagonist AB928/etrumadenant on CAR T cell function. Br. J. Cancer 2022, 127, 2175–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaljas, Y.; Liu, C.; Skaldin, M.; Wu, C.; Zhou, Q.; Lu, Y.; Aksentijevich, I.; Zavialov, A.V. Human adenosine deaminases ADA1 and ADA2 bind to different subsets of immune cells. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2017, 74, 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Phoon, Y.P.; Karlinsey, K.; Tian, Y.F.; Thapaliya, S.; Thongkum, A.; Qu, L.; Matz, A.J.; Cameron, M.; Cameron, C.; et al. A high OXPHOS CD8 T cell subset is predictive of immunotherapy resistance in melanoma patients. J. Exp. Med. 2022, 219, e20202084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Lan, Z.; Zou, K.L.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Yu, G.T. STAT3 promotes differentiation of monocytes to MDSCs via CD39/CD73-adenosine signal pathway in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2022, 72, 1315–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mager, L.F.; Burkhard, R.; Pett, N.; Cooke, N.C.A.; Brown, K.; Ramay, H.; Paik, S.; Stagg, J.; Groves, R.A.; Gallo, M.; et al. Microbiome-derived inosine modulates response to checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy. Science 2020, 369, 1481–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatano, R.; Ohnuma, K.; Yamamoto, J.; Dang, N.H.; Morimoto, C. CD26-mediated co-stimulation in human CD8(+) T cells provokes effector function via pro-inflammatory cytokine production. Immunology 2013, 138, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komiya, E.; Ohnuma, K.; Yamazaki, H.; Hatano, R.; Iwata, S.; Okamoto, T.; Dang, N.H.; Yamada, T.; Morimoto, C. CD26-mediated regulation of periostin expression contributes to migration and invasion of malignant pleural mesothelioma cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 447, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezawa, Y.; Daigo, Y.; Takano, A.; Miyagi, Y.; Yokose, T.; Yamashita, T.; Morimoto, C.; Hino, O.; Orimo, A. CD26 expression is attenuated by TGF-β and SDF-1 autocrine signaling on stromal myofibroblasts in human breast cancers. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 3936–3948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, M.H.; Knochelmann, H.M.; Bailey, S.R.; Huff, L.W.; Bowers, J.S.; Majchrzak-Kuligowska, K.; Wyatt, M.M.; Rubinstein, M.P.; Mehrotra, S.; Nishimura, M.I.; et al. Identification of human CD4(+) T cell populations with distinct antitumor activity. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaba7443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Min, P.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y. CD26 upregulates proliferation and invasion in keloid fibroblasts through an IGF-1-induced PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Burns Trauma. 2020, 8, tkaa025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordero, O.J.; Rafael-Vidal, C.; Varela-Calvino, R.; Calvino-Sampedro, C.; Malvar-Fernandez, B.; Garcia, S.; Vinuela, J.E.; Pego-Reigosa, J.M. Distinctive CD26 Expression on CD4 T-Cell Subsets. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R.P.; Tachibana, K.; Hegen, M.; Munakata, Y.; Cho, D.; Schlossman, S.F.; Morimoto, C. Determination of adenosine deaminase binding domain on CD26 and its immunoregulatory effect on T cell activation. J. Immunol. 1997, 159, 6070–6076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, E.; Alam, S.M.; Arredondo-Vega, F.X.; Patel, D.D.; Hershfield, M.S. Clustered charged amino acids of human adenosine deaminase comprise a functional epitope for binding the adenosine deaminase complexing protein CD26/dipeptidyl peptidase IV. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 19720–19726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, H.; Yan, S.; Stehling, S.; Marguet, D.; Schuppaw, D.; Reutter, W. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV/CD26 in T cell activation, cytokine secretion and immunoglobulin production. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2003, 524, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Gronow, M.; Hershfield, M.S.; Arredondo-Vega, F.X.; Pizzo, S.V. Cell surface adenosine deaminase binds and stimulates plasminogen activation on 1-LN human prostate cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 20993–20998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Gronow, M.; Grenett, H.E.; Gawdi, G.; Pizzo, S.V. Angiostatin directly inhibits human prostate tumor cell invasion by blocking plasminogen binding to its cellular receptor, CD26. Exp. Cell Res. 2005, 303, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preller, V.; Gerber, A.; Wrenger, S.; Togni, M.; Marguet, D.; Tadje, J.; Lendeckel, U.; Röcken, C.; Faust, J.; Neubert, K.; et al. TGF-beta1-mediated control of central nervous system inflammation and autoimmunity through the inhibitory receptor CD26. J. Immunol. 2007, 178, 4632–4640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havre, P.A.; Abe, M.; Urasaki, Y.; Ohnuma, K.; Morimoto, C.; Dang, N.H. CD26 expression on T cell lines increases SDF-1-alpha-mediated invasion. Br. J. Cancer 2009, 101, 983–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, S.; Sun, X.; Wang, Y.; Ye, J.; Wang, X.; Gu, Z.; Chen, Z. Tumor organoid and tumor-on-a-chip equipped next generation precision medicine. Biofabrication 2025, 17, 042006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Noguera-Ortega, E.; Dong, X.; Lee, W.D.; Chang, J.; Aydin, S.A.; Li, Y.; Shin, Y.; Shi, X.; Liousia, M.; et al. A tumor-on-a-chip for in vitro study of CAR-T cell immunotherapy in solid tumors. Nat. Biotechnol. 2025. epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bains, R.S.; Raju, T.G.; Semaan, L.C.; Block, A.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Priceman, S.J.; George, S.C.; Shirure, V.S. Vascularized tumor-on-a-chip to investigate immunosuppression of CAR-T cells. Lab. Chip 2025, 25, 2390–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, J.; Gust, J.A.; Vitanza, N.A.; Scott, B.; Monje, M.; Ronsley, R. Neurotoxicity in central nervous system tumors treated with CAR T cell therapy: A review. J. Neurooncol 2025, 176, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modoni, A.; Vollono, C.; Galli, E.; Capriati, L.; Sora, F.; Hohaus, S.; Servidei, S.; Piccirillo, N.; Calabresi, P.; Sica, S. Predictors of Neurotoxicity in a Large Cohort of Italian Patients Undergoing Anti-CD19 Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T-Cell Therapy. Brain Behav. 2025, 15, e70891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, P.; Agrawal, D.K. CAR T-Cell Therapy in Cancer: Balancing Efficacy with Cardiac Toxicity Concerns. J. Cancer Sci. Clin. Ther. 2025, 9, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, S.; Zhang, T.Y.; Wu, Z.L.; Xie, W.; Liu, L.; Du, M.Y. Novel Prognostic Scoring Systems for Severe CRS after Anti-CD19 CAR-T-Cells in Acute B-Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Curr. Med. Sci. 2025, 45, 1046–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ow, K.V. CAR T-Cell Therapy Unveiled: Navigating Beyond CRS and ICANS to Address Delayed Complications and Optimize Management Strategies. J. Adv. Pract. Oncol. 2025, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, S.R.; Nelson, M.H.; Majchrzak, K.; Bowers, J.S.; Wyatt, M.M.; Smith, A.S.; Neal, L.R.; Shirai, K.; Carpenito, C.; June, C.H.; et al. Human CD26high T cells elicit tumor immunity against multiple malignancies via enhanced migration and persistence. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Moreno, M.A.; Ciudad-Gutierrez, P.; Jaramillo-Ruiz, D.; Reguera-Ortega, J.L.; Abdel-Kader Martin, L.; Flores-Moreno, S. Combined or Sequential Treatment with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and Car-T Cell Therapies for the Management of Haematological Malignancies: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pondrelli, F.; Muccioli, L.; Mason, F.; Zenesini, C.; Ferri, L.; Asioli, G.M.; Rossi, S.; Rinaldi, R.; Rondelli, F.; Nicodemo, M.; et al. EEG as a predictive biomarker of neurotoxicity in anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy. J. Neurol. 2025, 272, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Song, Y. Serum ferritin as a prognostic biomarker in CAR-T therapy for multiple myeloma: A meta-analysis. Biomol. Biomed. 2025, 25, 2416–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, S.S.; Fei, T.; Fried, S.; Ip, A.; Fein, J.A.; Leslie, L.A.; Alarcon Tomas, A.; Leithner, D.; Peled, J.U.; Corona, M.; et al. An inflammatory biomarker signature of response to CAR-T cell therapy in non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 1183–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcuello, C.; Lim, K.; Nisini, G.; Pokrovsky, V.S.; Conde, J.; Ruggeri, F.S. Nanoscale Analysis beyond Imaging by Atomic Force Microscopy: Molecular Perspectives on Oncology and Neurodegeneration. Small Sci. 2025, 5, 2500351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocabey, S.; Cattin, S.; Gray, I.; Ruegg, C. Ultrasensitive detection of cancer-associated nucleic acids and mutations by primer exchange reaction-based signal amplification and flow cytometry. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2025, 267, 116839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Song, A.W.; Song, X. ADA1-Driven Metabolic Refueling Enhances CAR T Cell Therapy for Solid Tumors. Cancers 2026, 18, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010034

Song AW, Song X. ADA1-Driven Metabolic Refueling Enhances CAR T Cell Therapy for Solid Tumors. Cancers. 2026; 18(1):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010034

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Alex Wade, and Xiaotong Song. 2026. "ADA1-Driven Metabolic Refueling Enhances CAR T Cell Therapy for Solid Tumors" Cancers 18, no. 1: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010034

APA StyleSong, A. W., & Song, X. (2026). ADA1-Driven Metabolic Refueling Enhances CAR T Cell Therapy for Solid Tumors. Cancers, 18(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010034