Atezolizumab Plus Bevacizumab for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Macroscopic Vascular Invasion: An Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighted Analysis

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Eligibility

2.2. Atezo–Bev Treatment

2.3. TACE

2.4. External-Beam RT

2.5. Radiologic Response Assessment

2.6. Evaluation of Adverse Events

2.7. Definitions and Data Analysis

2.8. Propensity Score Weighting

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

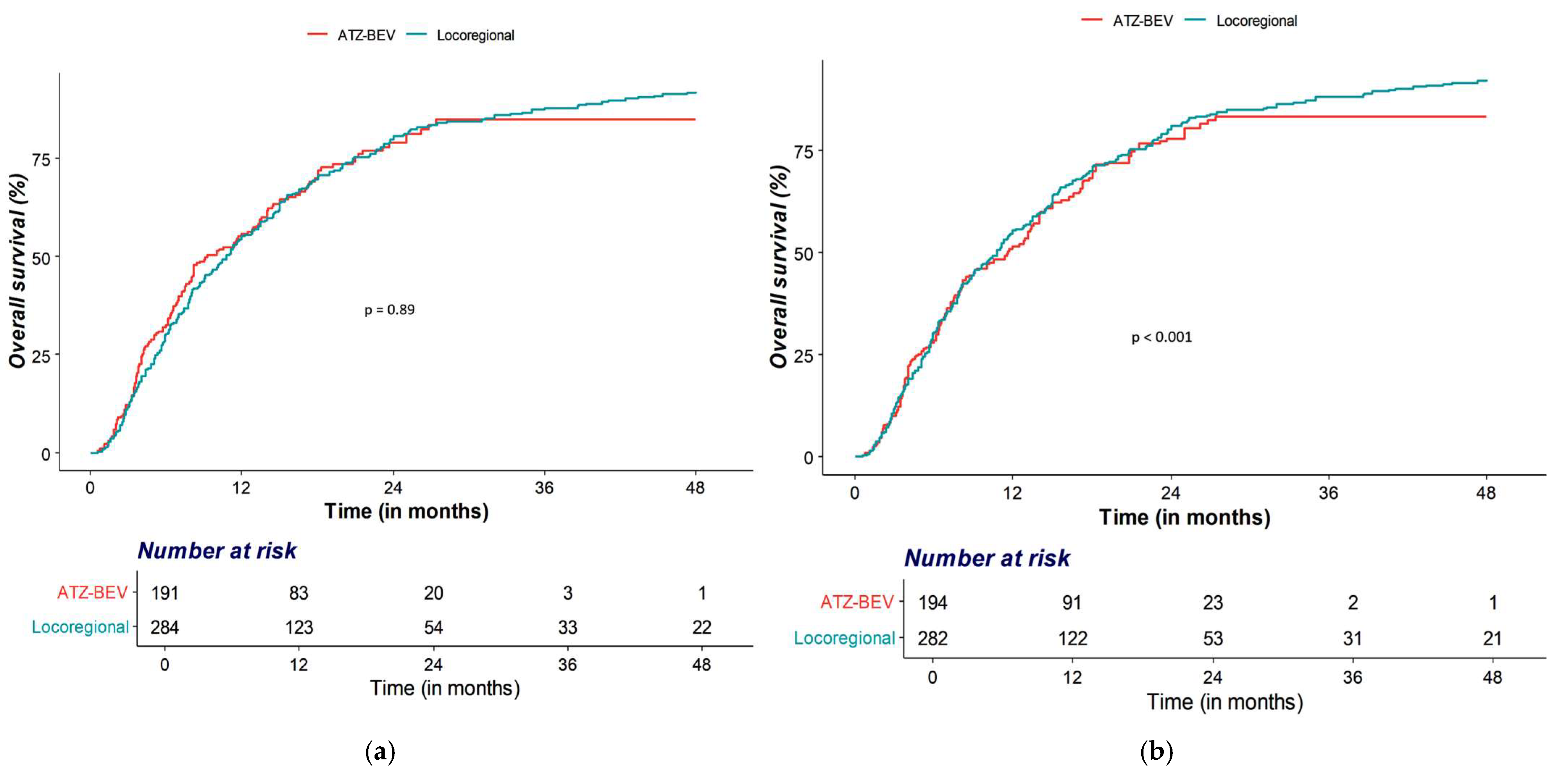

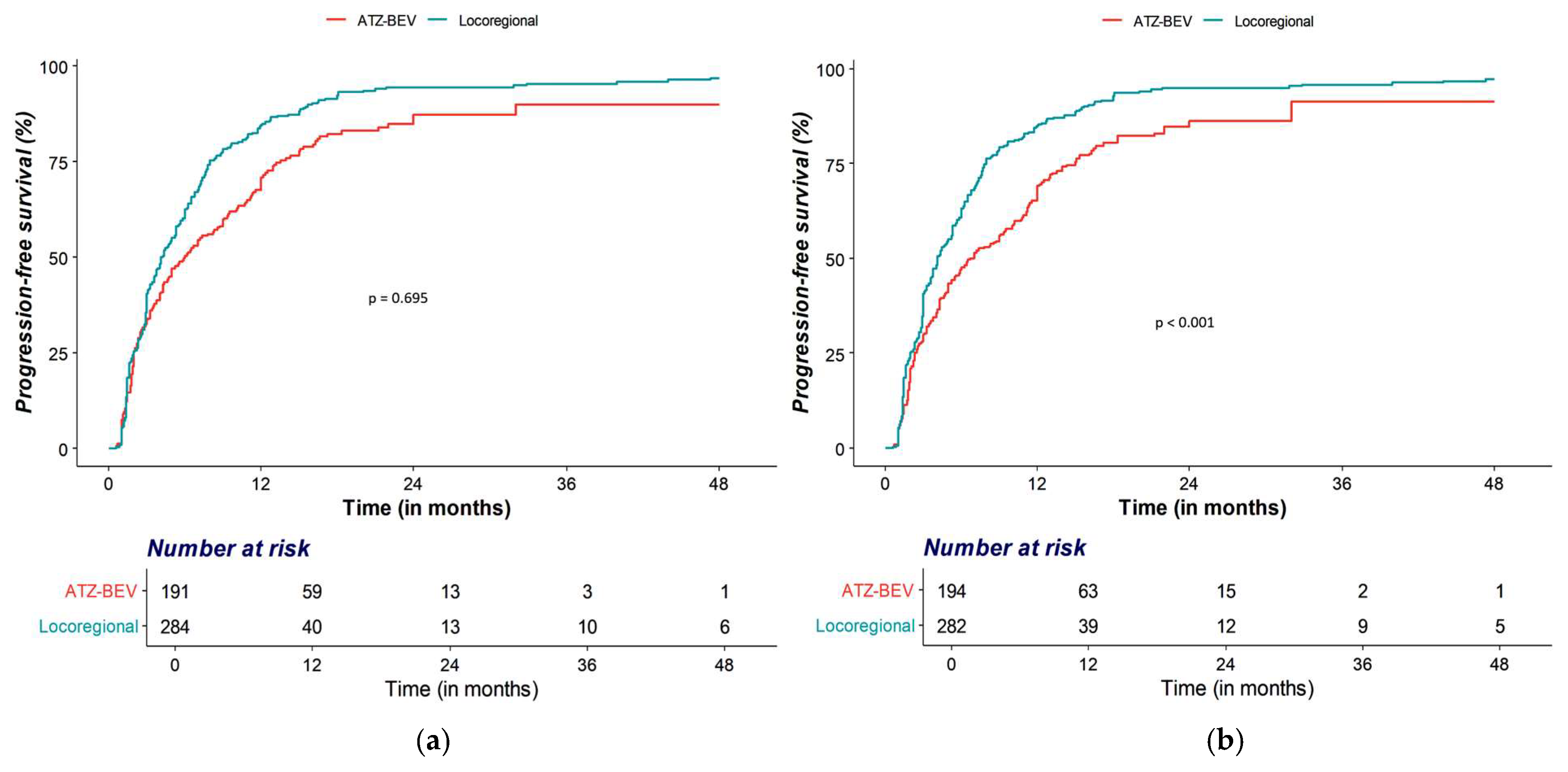

3.2. OS and PFS Analyses

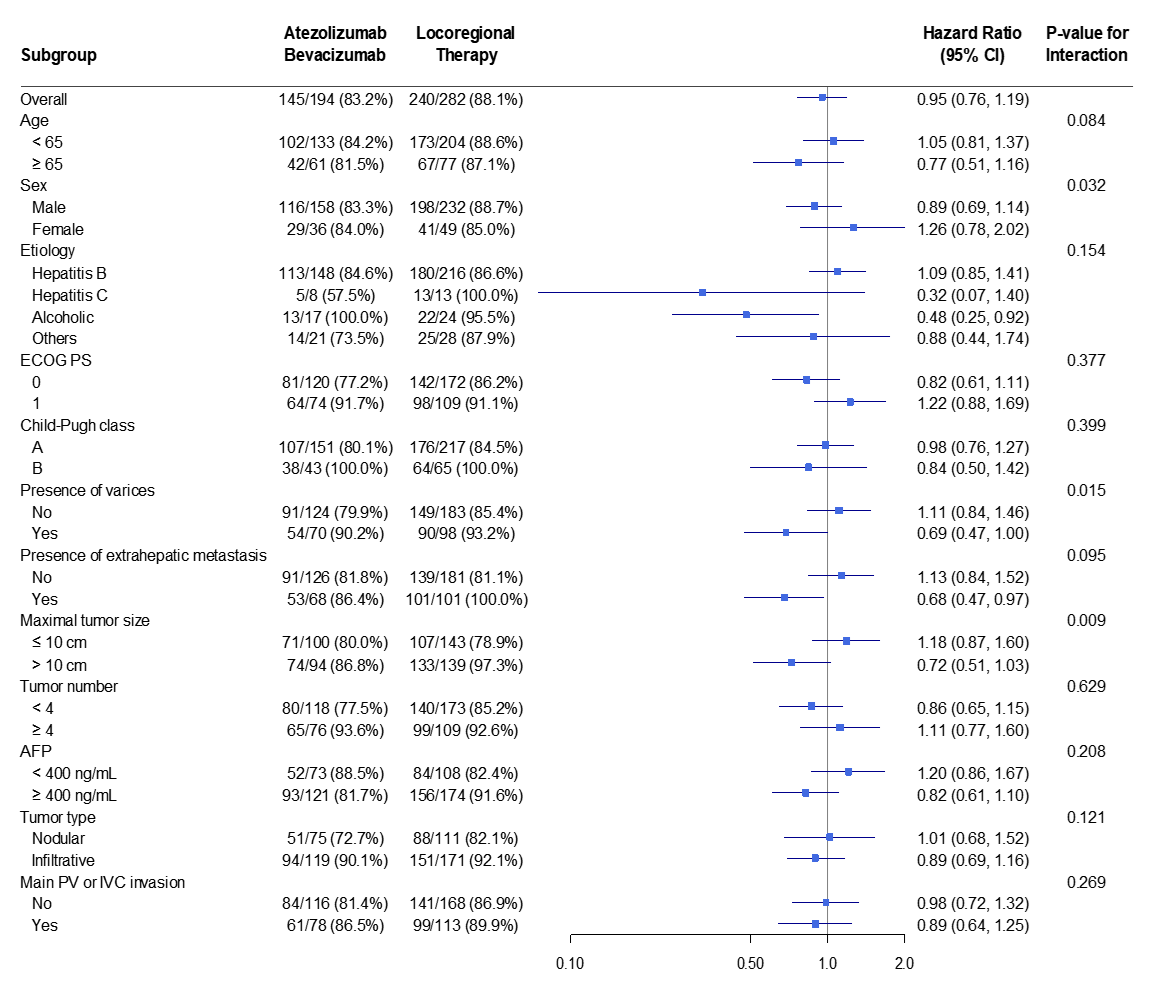

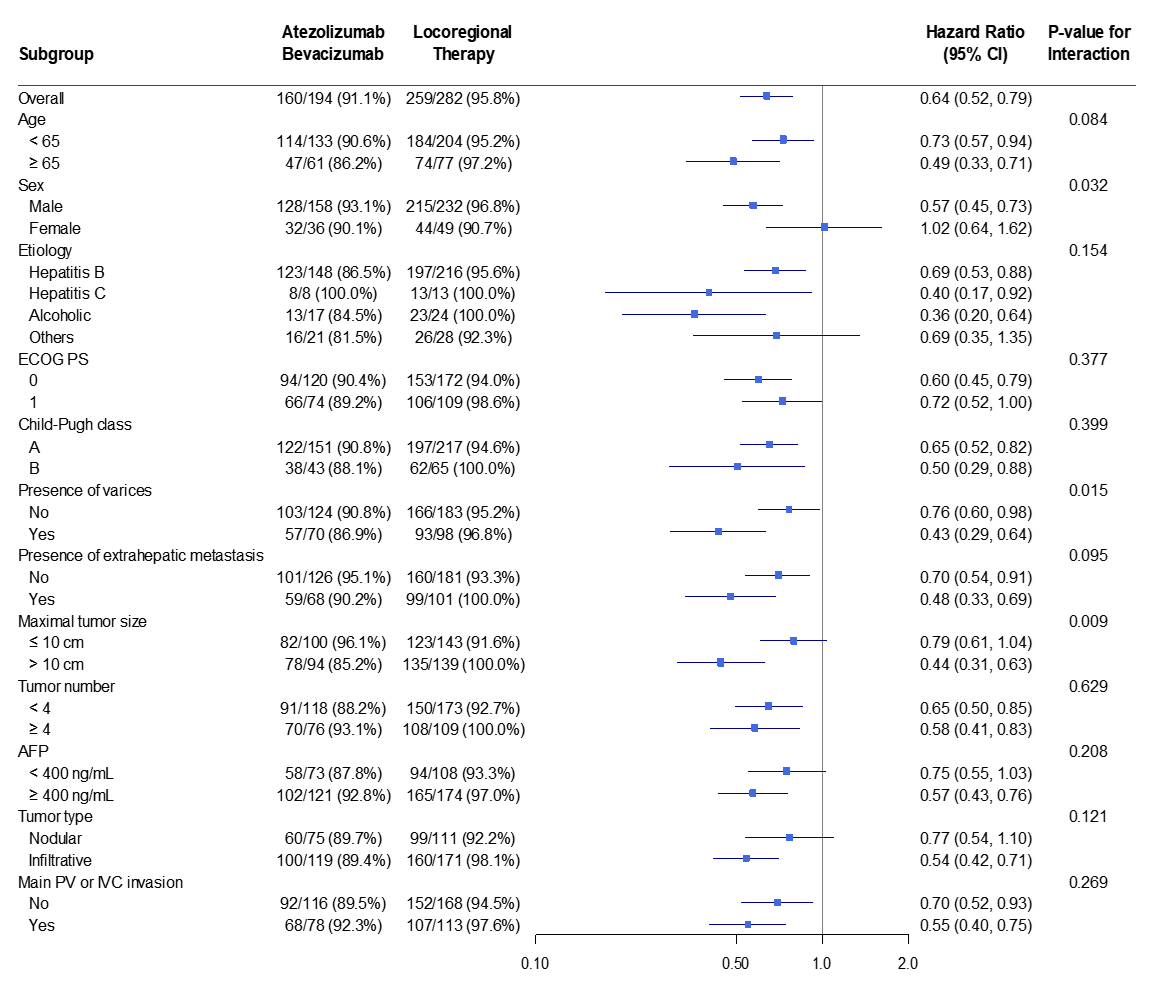

3.3. Subgroup Analyses

3.4. Radiologic Response After Treatment

3.5. Major Adverse Events

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| MVI | Macrovascular invasion |

| BCLC | Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer |

| Atezo–Bev | Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab |

| OS | Overall survival |

| PFS | Progression-free survival |

| TACE | Transarterial chemoembolization |

| RT | External-beam radiotherapy/Radiotherapy |

| PVTT | Portal vein tumor thrombosis |

| IPTW | Inverse probability of treatment weighting |

| ECOG | Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| mRECIST | Modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors |

| CR | Complete response |

| PR | Partial response |

| SD | Stable disease |

| PD | Progressive disease |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| AFP | Alpha-fetoprotein |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| GTV | Gross tumor volume |

| ITV | Internal target volume |

| PTV | Planning target volume |

| TARE | Transarterial radioembolization |

| TKI | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor |

| DNA-PK | DNA-dependent protein kinase |

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, A. Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1450–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, A.; Rimassa, L.; Sun, H.C.; Abou-Alfa, G.K.; El-Khoueiry, A.; Pinato, D.J.; Sanchez Alvarez, J.; Daigl, M.; Orfanos, P.; Leibfried, M.; et al. Comparative Efficacy of Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab and Other Treatment Options for Patients with Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Network Meta-Analysis. Liver Cancer 2021, 10, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reig, M.; Forner, A.; Rimola, J.; Ferrer-Fàbrega, J.; Burrel, M.; Garcia-Criado, Á.; Kelley, R.K.; Galle, P.R.; Mazzaferro, V.; Salem, R.; et al. BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: The 2022 update. J. Hepatol. 2022, 76, 681–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heimbach, J.K.; Kulik, L.M.; Finn, R.S.; Sirlin, C.B.; Abecassis, M.M.; Roberts, L.R.; Zhu, A.X.; Murad, M.H.; Marrero, J.A. AASLD guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2018, 67, 358–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.S.; Qin, S.; Ikeda, M.; Galle, P.R.; Ducreux, M.; Kim, T.Y.; Kudo, M.; Breder, V.; Merle, P.; Kaseb, A.O.; et al. Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1894–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, M.; Finn, R.S.; Galle, P.R.; Zhu, A.X.; Ducreux, M.; Cheng, A.L.; Ikeda, M.; Tsuchiya, K.; Aoki, K.I.; Jia, J.; et al. IMbrave150: Efficacy and Safety of Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab versus Sorafenib in Patients with Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer Stage B Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma: An Exploratory Analysis of the Phase III Study. Liver Cancer 2023, 12, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.L.; Qin, S.; Ikeda, M.; Galle, P.R.; Ducreux, M.; Kim, T.Y.; Lim, H.Y.; Kudo, M.; Breder, V.; Merle, P.; et al. Updated efficacy and safety data from IMbrave150: Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab vs. sorafenib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2022, 76, 862–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, A.V.; Tevethia, H.; Kumar, K.; Premkumar, M.; Muttaiah, M.D.; Hiraoka, A.; Hatanaka, T.; Tada, T.; Kumada, T.; Kakizaki, S.; et al. Effectiveness and safety of atezolizumab-bevacizumab in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 63, 102179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.G.; Goh, M.J.; Kang, W.; Sinn, D.H.; Gwak, G.-Y.; Choi, M.S.; Lee, J.H.; Paik, Y.-H. Analysis of Factors Predicting the Real-World Efficacy of Atezolizumab and Bevacizumab in Patients with Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gut Liver 2024, 18, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allaire, M.; Thiam, E.M.; Amaddeo, G.; Bouattour, M.; Edeline, J.; Brusset, B.; Ziol, M.; Merle, P.; Blanc, J.F.; Uguen, T.; et al. Real-World Outcomes of Atezolizumab-Bevacizumab in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: The Prospective French CHIEF Cohort. Liver Int. 2025, 45, e70337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheon, J.; Yoo, C.; Hong, J.Y.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, D.W.; Lee, M.A.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, I.; Oh, S.B.; Hwang, J.E.; et al. Efficacy and safety of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in Korean patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2022, 42, 674–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manfredi, G.F.; Fulgenzi, C.A.M.; Celsa, C.; Stefanini, B.; D’Alessio, A.; Pinter, M.; Scheiner, B.; Awosika, N.; Brunetti, L.; Lombardi, P.; et al. Efficacy of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab for unresectable HCC: Systematic review and meta-analysis of real-world evidence. JHEP Rep. 2025, 7, 101431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S.M.; Ryoo, B.Y.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, J.H.; Shin, J.H.; An, J.H.; Lee, H.C.; Lim, Y.S. Efficacy and Safety of Transarterial Chemoembolization Plus External Beam Radiotherapy vs Sorafenib in Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Macroscopic Vascular Invasion: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, M.J.; Sinn, D.H.; Kim, J.M.; Lee, M.W.; Hyun, D.H.; Yu, J.I.; Hong, J.Y.; Choi, M.S. Clinical practice guideline and real-life practice in hepatocellular carcinoma: A Korean perspective. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2023, 29, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.K.; Kwon, J.H.; Lee, S.W.; Lee, H.L.; Kim, H.Y.; Kim, C.W.; Song, D.S.; Chang, U.I.; Yang, J.M.; Nam, S.W.; et al. A Real-World Comparative Analysis of Atezolizumab Plus Bevacizumab and Transarterial Chemoembolization Plus Radiotherapy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients with Portal Vein Tumor Thrombosis. Cancers 2023, 15, 4423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrero, J.A.; Kulik, L.M.; Sirlin, C.B.; Zhu, A.X.; Finn, R.S.; Abecassis, M.M.; Roberts, L.R.; Heimbach, J.K. Diagnosis, Staging, and Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: 2018 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2018, 68, 723–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangro, B.; Argemi, J.; Ronot, M.; Paradis, V.; Meyer, T.; Mazzaferro, V.; Jepsen, P.; Golfieri, R.; Galle, P.; Dawson, L.; et al. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2025, 82, 315–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persano, M.; Rimini, M.; Tada, T.; Suda, G.; Shimose, S.; Kudo, M.; Rossari, F.; Yoo, C.; Cheon, J.; Finkelmeier, F.; et al. Adverse Events as Potential Predictive Factors of Activity in Patients with Advanced HCC Treated with Atezolizumab Plus Bevacizumab. Target. Oncol. 2024, 19, 645–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baerlocher, M.O.; Nikolic, B.; Sze, D.Y. Adverse Event Classification: Clarification and Validation of the Society of Interventional Radiology Specialty-Specific System. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2023, 34, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Shim, J.H.; Yoon, H.K.; Ko, H.K.; Kim, J.W.; Gwon, D.I. Chemoembolization related to good survival for selected patients with hepatocellular carcinoma invading segmental portal vein. Liver Int. 2018, 38, 1646–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Joo, J.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Choi, J.; Lee, D.; Shim, J.H.; Kim, K.M.; Lim, Y.S.; Lee, H.C.; et al. Radiologic Response as a Prognostic Factor in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Macroscopic Vascular Invasion after Transarterial Chemoembolization and Radiotherapy. Liver Cancer 2022, 11, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.J.; Jung, J.; Joo, J.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Lim, Y.S.; Lee, H.C.; Kim, J.H.; Yoon, S.M. Combined transarterial chemoembolization and radiotherapy as a first-line treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma with macroscopic vascular invasion: Necessity to subclassify Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage C. Radiother. Oncol. 2019, 141, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lencioni, R.; Llovet, J.M. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin. Liver Dis. 2010, 30, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lencioni, R.; Montal, R.; Torres, F.; Park, J.W.; Decaens, T.; Raoul, J.L.; Kudo, M.; Chang, C.; Ríos, J.; Boige, V.; et al. Objective response by mRECIST as a predictor and potential surrogate end-point of overall survival in advanced HCC. J. Hepatol. 2017, 66, 1166–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Chu, H.H.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Alrashidi, I.; Gwon, D.I.; Yoon, H.K.; Kim, N. Clinical Significance of the Initial and Best Responses after Chemoembolization in the Treatment of Intermediate-Stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Preserved Liver Function. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2020, 31, 1998–2006.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, N.; Wang, X.; Li, J.B.; Lai, J.F.; Chen, Q.F.; Li, S.L.; Deng, H.J.; He, M.; Mu, L.W.; Zhao, M. Arterial Chemotherapy of Oxaliplatin Plus Fluorouracil Versus Sorafenib in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Biomolecular Exploratory, Randomized, Phase III Trial (FOHAIC-1). J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 468–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Cho, Y.; Kim, S.U.; Kim, A.; Shin, H.; Kim, H.C.; Lee, I.J.; Kim, G.M.; Hyun, D.; Ko, Y.; et al. Transarterial radioembolization versus atezolizumab-bevacizumab for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombosis. Diagn. Interv. Imaging 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.H.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, P.H.; Chu, H.H.; Gwon, D.I.; Ko, H.-K. Emerging Trends in the Treatment of Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Radiological Perspective. Korean J. Radiol. 2021, 22, 1822–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, E.; Seruga, B.; Kwong, R.; Tannock, I.F.; Ocaña, A. Poor correlation between progression-free and overall survival in modern clinical trials: Are composite endpoints the answer? Eur. J. Cancer 2012, 48, 385–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.; Shim, J.H.; Kim, J.H. Hepatocellular carcinoma with macrovascular invasion: Need a personalized medicine for this complicated event. Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 2024, 13, 188–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.H.; Wang, K.; Zhang, X.P.; Feng, J.K.; Chai, Z.T.; Guo, W.X.; Shi, J.; Wu, M.C.; Lau, W.Y.; Cheng, S.Q. A new classification for hepatocellular carcinoma with hepatic vein tumor thrombus. Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 2020, 9, 717–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeckman, H.J.; Trego, K.S.; Turchi, J.J. Cisplatin sensitizes cancer cells to ionizing radiation via inhibition of nonhomologous end joining. Mol. Cancer Res. 2005, 3, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Zhao, M.; Arai, Y.; Zhong, B.Y.; Zhu, H.D.; Qi, X.L.; de Baere, T.; Pua, U.; Yoon, H.K.; Madoff, D.C.; et al. Clinical practice of transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: Consensus statement from an international expert panel of International Society of Multidisciplinary Interventional Oncology (ISMIO). Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 2021, 10, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, Y.; Kim, J.H.; Cheon, J.; Jeon, G.S.; Kim, C.; Chon, H.J. Risk of Variceal Bleeding in Patients with Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma Receiving Atezolizumab/Bevacizumab. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 21, 2421–2423.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thornton, L.M.; Abi-Jaoudeh, N.; Lim, H.J.; Malagari, K.; Spieler, B.O.; Kudo, M.; Finn, R.S.; Lencioni, R.; White, S.B.; Kokabi, N.; et al. Combination and Optimal Sequencing of Systemic and Locoregional Therapies in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Proceedings from the Society of Interventional Radiology Foundation Research Consensus Panel. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2024, 35, 818–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agirrezabal, I.; Bouattour, M.; Pinato, D.J.; D’Alessio, A.; Brennan, V.K.; Carion, P.L.; Shergill, S.; Amoury, N.; Vilgrain, V. Efficacy of transarterial radioembolization using Y-90 resin microspheres versus atezolizumab-bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A matching-adjusted indirect comparison. Eur. J. Cancer 2024, 196, 113427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Kim, G.H.; Gwon, D.I. Reappraisal of transarterial radioembolization for liver-confined hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombosis: Editorial on “Transarterial radioembolization versus tyrosine kinase inhibitor in hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein thrombosis”. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2024, 30, 659–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilgrain, V.; Pereira, H.; Assenat, E.; Guiu, B.; Ilonca, A.D.; Pageaux, G.P.; Sibert, A.; Bouattour, M.; Lebtahi, R.; Allaham, W.; et al. Efficacy and safety of selective internal radiotherapy with yttrium-90 resin microspheres compared with sorafenib in locally advanced and inoperable hepatocellular carcinoma (SARAH): An open-label randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 1624–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, P.K.H.; Gandhi, M.; Tan, S.B.; Khin, M.W.; Khasbazar, A.; Ong, J.; Choo, S.P.; Cheow, P.C.; Chotipanich, C.; Lim, K.; et al. SIRveNIB: Selective Internal Radiation Therapy Versus Sorafenib in Asia-Pacific Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 1913–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garin, E.; Tselikas, L.; Guiu, B.; Chalaye, J.; Edeline, J.; de Baere, T.; Assenat, E.; Tacher, V.; Robert, C.; Terroir-Cassou-Mounat, M.; et al. Personalised versus standard dosimetry approach of selective internal radiation therapy in patients with locally advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (DOSISPHERE-01): A randomised, multicentre, open-label phase 2 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 6, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casak, S.J.; Donoghue, M.; Fashoyin-Aje, L.; Jiang, X.; Rodriguez, L.; Shen, Y.L.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, X.; Liu, J.; Zhao, H.; et al. FDA Approval Summary: Atezolizumab Plus Bevacizumab for the Treatment of Patients with Advanced Unresectable or Metastatic Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 1836–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Unadjusted | IPTW-Weighted | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atezolizumab–Bevacizumab (n = 191) | Locoregional Therapy (n = 284) | ASD | p * | Atezolizumab–Bevacizumab (n = 194) | Locoregional Therapy (n = 282) | ASD | p * | |

| Age | 58.98 (10.89) | 57.96 (10.69) | 0.095 | 0.311 | 58.55 (10.72) | 58.20 (10.82) | 0.033 | 0.745 |

| Sex (%) | 0.033 | 0.722 | 0.028 | 0.784 | ||||

| Male | 157 (82.2) | 237 (83.5) | 158.0 (81.4) | 232.4 (82.5) | ||||

| Female | 34 (17.8) | 47 (16.5) | 36.1 (18.6) | 49.3 (17.5) | ||||

| Etiology | 0.231 | 0.108 | 0.028 | 0.994 | ||||

| HBV | 139 (72.8) | 223 (78.5) | 148.0 (76.3) | 216.3 (76.8) | ||||

| HCV | 6 (3.1) | 16 (5.6) | 8.4 (4.3) | 13.1 (4.7) | ||||

| Alcohol | 20 (10.5) | 20 (7.0) | 16.6 (8.5) | 23.7 (8.4) | ||||

| Others | 26 (13.6) | 25 (8.8) | 21.0 (10.8) | 28.5 (10.1) | ||||

| ECOG PS | 0.337 | <0.001 | 0.009 | 0.93 | ||||

| 0 | 98 (51.3) | 192 (67.6) | 119.6 (61.6) | 172.4 (61.2) | ||||

| 1 | 93 (48.7) | 92 (32.4) | 74.4 (38.4) | 109.2 (38.8) | ||||

| Child–Pugh class | 0.055 | 0.56 | 0.022 | 0.827 | ||||

| A | 149 (78.0) | 215 (75.7) | 150.9 (77.8) | 216.5 (76.9) | ||||

| B | 42 (22.0) | 69 (24.3) | 43.1 (22.2) | 65.2 (23.1) | ||||

| Presence of varices | 0.356 | <0.001 | 0.024 | 0.818 | ||||

| Present | 145 (75.9) | 169 (59.5) | 124.0 (63.9) | 183.3 (65.1) | ||||

| Absent | 46 (24.1) | 115 (40.5) | 70.0 (36.1) | 98.4 (34.9) | ||||

| Extrahepatic metastasis | 0.282 | 0.003 | 0.018 | 0.854 | ||||

| Present | 106 (55.5) | 196 (69.0) | 126.4 (65.2) | 181.1 (64.3) | ||||

| Absent | 85 (44.5) | 88 (31.0) | 67.6 (34.8) | 100.5 (35.7) | ||||

| Maximal tumor size | 0.047 | 0.613 | 0.015 | 0.881 | ||||

| ≤10 cm | 93 (48.7) | 145 (51.1) | 99.6 (51.4) | 142.5 (50.6) | ||||

| >10 cm | 98 (51.3) | 139 (48.9) | 94.4 (48.6) | 139.1 (49.4) | ||||

| Number of tumors | 0.018 | 0.843 | 0.013 | 0.897 | ||||

| <4 | 118 (61.8) | 178 (62.7) | 117.6 (60.6) | 172.6 (61.3) | ||||

| ≥4 | 73 (38.2) | 106 (37.3) | 76.4 (39.4) | 109.1 (38.7) | ||||

| AFP | 0.014 | 0.877 | 0.017 | 0.867 | ||||

| < 400 ng/mL | 76 (39.8) | 111 (39.1) | 72.8 (37.5) | 107.9 (38.3) | ||||

| ≥400 ng/mL | 115 (60.2) | 173 (60.9) | 121.3 (62.5) | 173.8 (61.7) | ||||

| Tumor type | 0.143 | 0.126 | 0.014 | 0.889 | ||||

| Nodular | 84 (44.0) | 105 (37.0) | 75.1 (38.7) | 111.0 (39.4) | ||||

| Infiltrative | 107 (56.0) | 179 (63.0) | 118.9 (61.3) | 170.7 (60.6) | ||||

| Main PV or IVC invasion | 0.129 | 0.17 | <0.001 | 0.998 | ||||

| Present | 107 (56.0) | 177 (62.3) | 115.9 (59.7) | 168.2 (59.7) | ||||

| Absent | 84 (44.0) | 107 (37.7) | 78.1 (40.3) | 113.5 (40.3) | ||||

| Unadjusted Sample | IPTW-Weighted Sample | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) * | p | |

| OS | Locoregional therapy | Ref | Ref | ||

| Atezolizumab–Bevacizumab | 1.03 (0.84–1.26) | 0.794 | 0.95 (0.76–1.19) | 0.635 | |

| PFS | Locoregional therapy | Ref | Ref | ||

| Atezolizumab–Bevacizumab | 0.70 (0.58–0.86) | <0.001 | 0.64 (0.52–0.79) | <0.001 | |

| Unadjusted Sample | IPTW-Weighted Sample | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atezolizumab–Bevacizumab (n = 191) | Locoregional Therapy (n = 284) | p | Atezolizumab–Bevacizumab (n = 194) | Locoregional Therapy (n = 282) | p | ||

| Objective response | Responder | 86 (45.0) | 137 (48.2) | 0.491 | 92.5 (47.7) | 135.1 (47.9) | 0.957 |

| Non-responder | 105 (55.0) | 147 (51.8) | 101.5 (52.3) | 146.6 (52.1) | |||

| Major adverse event | Present | 170 (89.0) | 252 (88.7) | 0.926 | 172.0 (88.6) | 249.6 (88.6) | 0.993 |

| Absent | 21 (11.0) | 32 (11.3) | 22.1 (11.4) | 32.1 (11.4) | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kim, J.; Kim, J.-H.; Im, B.S.; Kim, G.H.; Chu, H.H.; Gwon, D.I.; Shin, J.H.; Shim, J.H.; Yoon, S.M.; Kim, S. Atezolizumab Plus Bevacizumab for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Macroscopic Vascular Invasion: An Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighted Analysis. Cancers 2026, 18, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010033

Kim J, Kim J-H, Im BS, Kim GH, Chu HH, Gwon DI, Shin JH, Shim JH, Yoon SM, Kim S. Atezolizumab Plus Bevacizumab for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Macroscopic Vascular Invasion: An Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighted Analysis. Cancers. 2026; 18(1):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010033

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Jihoon, Jin-Hyoung Kim, Byung Soo Im, Gun Ha Kim, Hee Ho Chu, Dong Il Gwon, Ji Hoon Shin, Ju Hyun Shim, Sang Min Yoon, and Sehee Kim. 2026. "Atezolizumab Plus Bevacizumab for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Macroscopic Vascular Invasion: An Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighted Analysis" Cancers 18, no. 1: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010033

APA StyleKim, J., Kim, J.-H., Im, B. S., Kim, G. H., Chu, H. H., Gwon, D. I., Shin, J. H., Shim, J. H., Yoon, S. M., & Kim, S. (2026). Atezolizumab Plus Bevacizumab for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Macroscopic Vascular Invasion: An Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighted Analysis. Cancers, 18(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010033