Assessment of Network Integrity in Right-Hemispheric Glioma Patients Using Function-Based Tractography and Domain-Specific Cognitive Testing

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Enrollment

2.2. Cognitive Testing

2.2.1. Task Overview

2.2.2. Interpretation of Cognitive Results

2.3. Function-Based Analysis of Structural Imaging

2.4. Analysis of Imaging and Functional Status

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Data

3.2. Neurocognitive Testing

3.3. Tumor Location

3.4. Tumor Grading

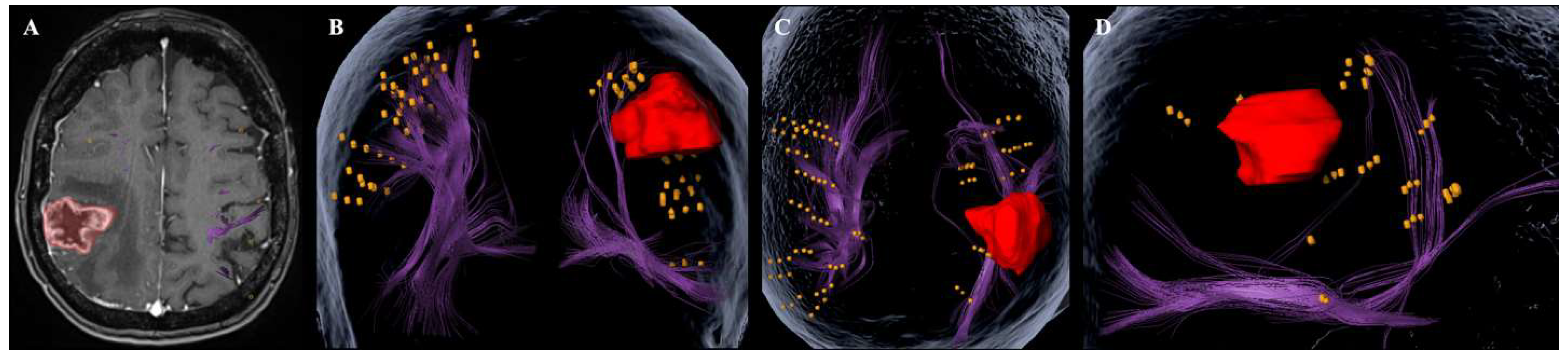

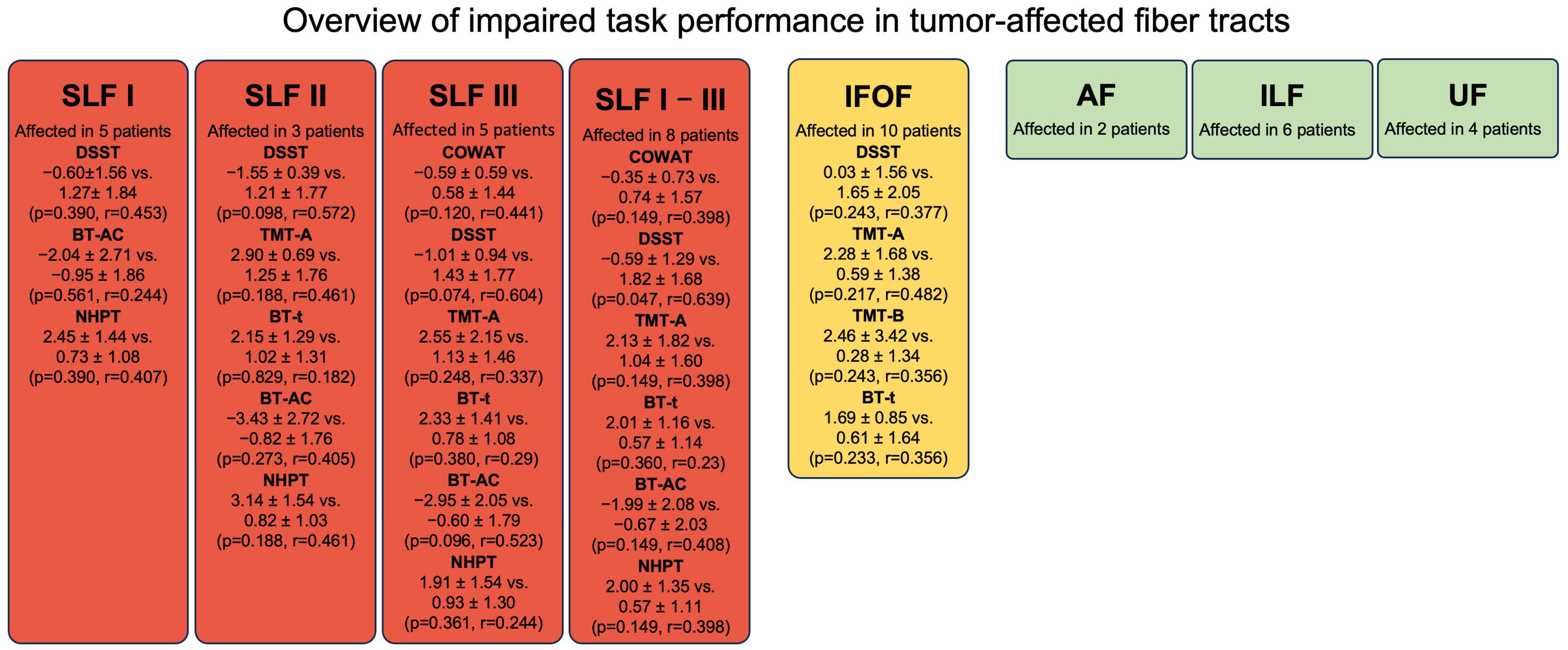

3.5. Preoperative Mapping and Function-Based Fiber Tracking

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Results

4.2. Task Selection

4.3. Structure-Function Correlation

4.4. Clinical Implications

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AF | Arcuate fasciculus |

| BT-AC | Bells Test accuracy score |

| BT-AS | Bells Test asymmetry score |

| BT-t | Bells Tes task completion time |

| COWAT | Controlled oral word association test |

| DSST | Digit symbol substitution test |

| FU | Follow-up |

| HGG | High-grade glioma |

| HVLTR | Hopkins verbal learning test revised |

| IFOF | Inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus |

| ILF | Inferior longitudinal fasciculus |

| LGG | Low-grade glioma |

| MoCA | Montreal cognitive assessment |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| NHPT | Nine-hole peg test |

| nTMS | Navigated transcranial magnetic stimulation |

| SLF I | Superior longitudinal fasciculus I |

| SLF II | Superior longitudinal fasciculus II |

| SLF III | Superior longitudinal fasciculus III |

| TMT-A | Trail making test part A |

| TMT-B | Trail making test part B |

| UF | Uncinate fasciculus |

| WHO CNS | Tumor grades according to the World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System |

References

- Ramirez-Ferrer, E.; Aguilera-Pena, M.P.; Duffau, H. Functional and oncological outcomes after right hemisphere glioma resection in awake versus asleep patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurg. Rev. 2024, 47, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehring, K.; Taphoorn, M.J.; Sitskoorn, M.M.; Aaronson, N.K.; Dirven, L.; Armstrong, T.S. Predictors of subjective versus objective cognitive functioning in patients with stable grades II and III glioma. Neuro-Oncol. Pract. 2015, 2, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pertz, M.; Kowalski, T.; Jetschke, K.; Schmieder, K.; Schlegel, U.; Miller, D. Pre- and postoperative self-reported and objectively assessed neurocognitive functioning in lower grade glioma patients. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2022, 106, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuster, J.M. The cognit: A network model of cortical representation. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2006, 60, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanai, R.; Rees, G. The structural basis of inter-individual differences in human behaviour and cognition. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2011, 12, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habets, E.J.J.; Kloet, A.; Walchenbach, R.; Vecht, C.J.; Klein, M.; Taphoorn, M.J.B. Tumour and surgery effects on cognitive functioning in high-grade glioma patients. Acta Neurochir. 2014, 156, 1451–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucha, O.; Smely, C.; Preier, M.; Lange, K.W. Cognitive deficits before treatment among patients with brain tumors. Neurosurgery 2000, 47, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, F.; Lemee, J.M.; Ter Minassian, A.; Menei, P. Right Hemisphere Cognitive Functions: From Clinical and Anatomic Bases to Brain Mapping During Awake Craniotomy Part I: Clinical and Functional Anatomy. World Neurosurg. 2018, 118, 348–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, A.; Britt, C.; Woods, R.L.; Orchard, S.G.; Murray, A.M.; Shah, R.C.; Rajan, R.; McNeil, J.J.; Chong, T.T.-J.; Storey, E.; et al. Normative Data for Single-Letter Controlled Oral Word Association Test in Older White Australians and Americans, African-Americans, and Hispanic/Latinos. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Rep. 2023, 7, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalobos, D.; Torres-Simón, L.; Pacios, J.; Paúl, N.; del Río, D. A Systematic Review of Normative Data for Verbal Fluency Test in Different Languages. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2023, 33, 733–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, Z.S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bédirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Cummings, J.L.; Chertkow, H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomann, A.E.; Goettel, N.; Monsch, R.J.; Berres, M.; Jahn, T.; Steiner, L.A.; Monsch, A.U. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment: Normative Data from a German-Speaking Cohort and Comparison with International Normative Samples. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 64, 643–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duff, K. Demographically corrected normative data for the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised and Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised in an elderly sample. Appl. Neuropsychol. Adult 2015, 23, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J.; Woods, R.L.; Murray, A.M.; Shah, R.C.; Britt, C.J.; Reid, C.M.; Wolfe, R.; Nelson, M.R.; Lockery, J.E.; Orchard, S.G.; et al. Normative performance of older individuals on the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised (HVLT-R) according to ethno-racial group, gender, age and education level. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2021, 35, 1174–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, J.J.; Woods, R.L.; Britt, C.J.; Murray, A.M.; Shah, R.C.; Reid, C.M.; Wolfe, R.; Nelson, M.R.; Orchard, S.G.; Lockery, J.E.; et al. Normative Data for the Symbol Digit Modalities Test in Older White Australians and Americans, African-Americans, and Hispanic/Latinos. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Rep. 2020, 4, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaeger, J. Digit Symbol Substitution Test: The Case for Sensitivity Over Specificity in Neuropsychological Testing. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2018, 38, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wechsler, D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Fourth Edition (WAIS-IV); APA PsycTests; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombaugh, T. Trail Making Test A and B: Normative data stratified by age and education. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2004, 19, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitan, R.M. The relation of the trail making test to organic brain damage. J. Consult. Psychol. 1955, 19, 393–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, M.; Damora, A.; Abbruzzese, L.; Navarrete, E.; Basagni, B.; Galardi, G.; Caputo, M.; Bartalini, B.; Bartolo, M.; Zucchella, C.; et al. A New Standardization of the Bells Test: An Italian Multi-Center Normative Study. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, L.; Dehaut, F.; Joanette, Y. The Bells Test: A quantitative and qualitative test for visual neglect. Int. J. Clin. Neuropsychol. 1989, 11, 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Grice, K.O.; Vogel, K.A.; Le, V.; Mitchell, A.; Muniz, S.; Vollmer, M.A. Adult norms for a commercially available Nine Hole Peg Test for finger dexterity. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2003, 57, 570–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.; Rigau, V.; Moritz-Gasser, S.; Gozé, C.; Darlix, A.; Herbet, G.; Duffau, H. Long-term autonomy, professional activities, cognition, and overall survival after awake functional-based surgery in patients with IDH-mutant grade 2 gliomas: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2024, 46, 101078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, D.; Patterson, K.E. The Pyramids and Palm Trees Test; Thames Valley Test Company: Bury St. Edmunds, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Corina, D.P.; Gibson, E.K.; Martin, R.; Poliakov, A.; Brinkley, J.; Ojemann, G.A. Dissociation of action and object naming: Evidence from cortical stimulation mapping. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2005, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sollmann, N.; Meyer, B.; Krieg, S.M. Implementing Functional Preoperative Mapping in the Clinical Routine of a Neurosurgical Department: Technical Note. World Neurosurg. 2017, 103, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Wesseling, P.; Brat, D.J.; Cree, I.A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Hawkins, C.; Ng, H.K.; Pfister, S.M.; Reifenberger, G.; et al. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: A summary. Neuro Oncol. 2021, 23, 1231–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwan, T.M.; Ownsworth, T.; Chambers, S.; Walker, D.G.; Shum, D.H.K. Neuropsychological assessment of individuals with brain tumor: Comparison of approaches used in the classification of impairment. Front. Oncol. 2015, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.; Herbet, G.; Lemaitre, A.-L.; Cochereau, J.; Moritz-Gasser, S.; Duffau, H. Neuropsychological assessments before and after awake surgery for incidental low-grade gliomas. J. Neurosurg. 2020, 135, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwigsen, G.; Bengio, Y.; Bzdok, D. How does hemispheric specialization contribute to human-defining cognition? Neuron. 2021, 109, 2075–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartikainen, K.M. Emotion-Attention Interaction in the Right Hemisphere. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamali, A.; Flanders, A.E.; Brody, J.; Hunter, J.V.; Hasan, K.M. Tracing superior longitudinal fasciculus connectivity in the human brain using high resolution diffusion tensor tractography. Brain Struct. Funct. 2014, 219, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janelle, F.; Iorio-Morin, C.; D’Amour, S.; Fortin, D. Superior Longitudinal Fasciculus: A Review of the Anatomical Descriptions With Functional Correlates. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 794618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giampiccolo, D.; Herbet, G.; Duffau, H. The inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus: Bridging phylogeny, ontogeny and functional anatomy. Brain 2025, 148, 1507–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, T.R.J.G.; Arias, J.C.; Jefferies, E.; Smallwood, J.; Leemans, A.; Davolos, J.M. Ventral and dorsal aspects of the inferior frontal-occipital fasciculus support verbal semantic access and visually-guided behavioural control. Brain Struct. Funct. 2024, 229, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbet, G.; Moritz-Gasser, S.; Duffau, H. Direct evidence for the contributive role of the right inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus in non-verbal semantic cognition. Brain Struct. Funct. 2017, 222, 1597–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbet, G.; Zemmoura, I.; Duffau, H. Functional Anatomy of the Inferior Longitudinal Fasciculus: From Historical Reports to Current Hypotheses. Front. Neuroanat. 2018, 12, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralph, M.A.L.; Cipolotti, L.; Manes, F.; Patterson, K. Taking both sides: Do unilateral anterior temporal lobe lesions disrupt semantic memory? Brain. 2010, 133, 3243–3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, G.E.; Hoffman, P.; Ralph, M.A.L. Graded specialization within and between the anterior temporal lobes. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2015, 1359, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandonnet, E.; Nouet, A.; Gatignol, P.; Capelle, L.; Duffau, H. Does the left inferior longitudinal fasciculus play a role in language? A brain stimulation study. Brain 2007, 130, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavassori, L.; Venturini, M.; Zigiotto, L.; Annicchiarico, L.; Corsini, F.; Avesani, P.; Petit, L.; De Benedictis, A.; Sarubbo, S. The arcuate fasciculus: Combining structure and function into surgical considerations. Brain Behav. 2023, 13, e3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamadaliev, D.M.; Saito, R.; Motomura, K.; Ohka, F.; Scalia, G.; Umana, G.E.; Conti, A.; Chaurasia, B. Awake Craniotomy for Gliomas in the Non-Dominant Right Hemisphere: A Comprehensive Review. Cancers 2024, 16, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvaniti, C.K.; Karagianni, M.D.; Papageorgakopoulou, M.A.; Brotis, A.G.; Tasiou, A.; Fountas, K.N. The role of lobectomy in glioblastoma management: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Spine 2024, 4, 102823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieberlein, L.; Rampp, S.; Gussew, A.; Prell, J.; Hartwigsen, G. Reorganization and Plasticity of the Language Network in Patients with Cerebral Gliomas. Neuroimage Clin. 2023, 37, 103326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, M.; Rössler, K.; Kaltenhäuser, M.; Grummich, P.; Yang, B.; Buchfelder, M.; Doerfler, A.; Kölble, K.; Stadlbauer, A. Refined Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Magnetoencephalography Mapping Reveals Reorganization in Language-Relevant Areas of Lesioned Brains. World Neurosurg. 2020, 136, e41–e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieg, S.M.; Sollmann, N.; Hauck, T.; Ille, S.; Foerschler, A.; Meyer, B.; Ringel, F. Functional language shift to the right hemisphere in patients with language-eloquent brain tumors. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e75403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ille, S.; Engel, L.; Albers, L.; Schroeder, A.; Kelm, A.; Meyer, B.; Krieg, S.M. Functional Reorganization of Cortical Language Function in Glioma Patients-A Preliminary Study. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajardo-Vidal, A.; Lorca-Puls, D.L.; Hope, T.M.H.; Jones, O.P.; Seghier, M.L.; Prejawa, S.; Crinion, J.T.; Leff, A.P.; Green, D.W.; Price, C.J. How right hemisphere damage after stroke can impair speech comprehension. Brain 2018, 141, 3389–3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, A.K. In your right mind: Right hemisphere contributions to language processing and production. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2006, 16, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fava, A.; Lisi, S.V.; Mauro, L.; Morace, R.; Ciavarro, M.; Gorgoglione, N.; Petrella, G.; Quarato, P.P.; Di Gennaro, G.; di Russo, P.; et al. The anterior sylvian point as a reliable landmark for the anterior temporal lobectomy in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy: Technical note, case series, and cadaveric dissection. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1352321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morshed, R.A.; Young, J.S.; Kroliczek, A.A.; Berger, M.S.; Brang, D.; Hervey-Jumper, S.L. A Neurosurgeon’s Guide to Cognitive Dysfunction in Adult Glioma. Neurosurgery 2021, 89, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, C.; Wegrzyn, M.; Wiedl, A.; Ackermann, V.; Ehrenreich, H. Practice effects in healthy adults: A longitudinal study on frequent repetitive cognitive testing. BMC Neurosci. 2010, 11, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number of Patients (n) | 18 |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 10 (56%) |

| Female | 8 (44%) |

| Age (Mean ± SD) | 52.7 ± 18.3 years |

| Hemisphere (n (%)) | |

| Left | 0 (0%) |

| Right | 18 (100%) |

| Localization (n (%)) | |

| Frontal | 5 (28%) |

| Parietal | 2 (11%) |

| Temporal | 7 (39%) |

| Temporoinsular | 1 (6%) |

| Frontoinsular | 1 (6%) |

| Occipital | 1 (6%) |

| Basal ganglia | 1 (6%) |

| WHO CNS degree (n (%)) | |

| °1 | 1 (6%) |

| °2 | 4 (22%) |

| °3 | 2 (11%) |

| °4 | 11 (61%) |

| Tumor volume (Mean ± SD) | 33.0 ± 20.5 cm3 |

| Fiber volume (Mean ± SD) | 41.8 ± 22.7 cm3 |

| Domain | Neuro-Cognitive Test | Preoperative z-Scores Mean (SD) | Postoperative z-Scores Mean (SD) | p-Value Pre-Post | Follow-Up z-Scores Mean (SD) | p-Value Pre-FU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language | COWAT | 0.26 ± 1.35 | 0.04 ± 0.91 | 0.871 | 0.35 ± 1.66 | 0.772 |

| Episodic memory | HVLTR | 0.01 ± 0.80 | −0.16 ± 0.82 | 0.339 | 0.27 ± 0.61 | 0.744 |

| Processing speed | DSST | 0.75 ± 1.92 | 0.32 ± 1.87 | 0.339 | 0.59 ± 2.14 | 0.744 |

| TMT-A | 1.53 ± 1.74 | 2.13 ± 2.47 | 0.339 | 1.14 ± 1.94 | 0.744 | |

| BT-t | 1.21 ± 1.34 | 1.39 ± 1.24 | 0.405 | 0.45 ± 1.25 | 0.333 | |

| Attention and executive function | TMT-B | 1.49 ± 2.86 | 1.95 ± 2.82 | 0.339 | 0.62 ± 2.87 | 0.333 |

| Visuospatial function | BT-AC | −1.25 ± 2.10 | −1.18 ± 2.99 | 0.904 | −1.04 ± 2.30 | 0.744 |

| BT-AS | 0.01 ± 1.63 | 0.79 ± 2.23 | 0.339 | −0.24 ± 1.47 | 0.744 | |

| Coordination | NHPT | 1.21 ± 1.40 | 2.37 ± 2.24 | 0.123 | 1.27 ± 2.01 | 0.744 |

| Screening | MoCA | 0.54 ± 1.06 | 0.48 ± 1.26 | 0.947 | 0.46 ± 1.15 | 0.744 |

| Patients (n) | COWAT | MOCA | DSST | HVLT | TMT-A | TMT-B | BT-t | BT-AC | BT-AS | NHPT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| temporal | 7 | 0.82 ± 1.96 | 0.88 ± 1.15 | 1.42 ± 2.06 | −0.07 ± 1.05 | 1.21 ± 2.08 | 0.68 ± 1.50 | 0.89 ± 1.26 | −0.97 ± 2.06 | −1.08 ± 1.78 | 0.44 ± 0.91 |

| frontal | 5 | −0.24 ± 0.41 | 0.97 ± 0.92 | 0.13 ± 1.34 | −0.06 ± 0.60 | 1.38 ± 0.81 | 0.84 ± 1.42 | 1.29 ± 0.57 | −0.60 ± 1.31 | 0.66 ± 0.59 | 1.60 ± 0.36 |

| parietal | 2 | −0.89 ± 0.31 | −0.44 ± 0.52 | −1.25 ± 1.05 | −0.11 ± 0.40 | 3.98 ± 0.42 | 4.37 ± 1.97 | 2.28 ± 1.91 | −5.18 ± 1.85 | 0.55 ± 0.76 | 3.08 ± 1.85 |

| insular | 2 | 0.09 ± 0.77 | −0.26 ± 0.79 | 1.99 ± 2.28 | 0.30 ± 1.38 | −0.38 ± 1.00 | −0.58 ± 1.12 | 1.09 ± 3.60 | −0.93 ± 1.39 | 1.10 ± 3.08 | −0.40 ± 1.03 |

| occipital | 1 | 0.85 ± 0.00 | 1.04 ± 0.00 | −1.25 ± 0.00 | 0.72 ± 0.00 | 2.63 ± 0.00 | −0.01 ± 0.00 | 1.28 ± 0.00 | −1.25 ± 0.00 | 1.09 ± 0.00 | 3.61 ± 0.00 |

| basal ganglia | 1 | 0.85 ± 0.00 | −0.81 ± 0.00 | 2.72 ± 0.00 | −0.11 ± 0.00 | 2.21 ± 0.00 | 10.30 ± 0.00 | 1.15 ± 0.00 | 0.71 ± 0.00 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 1.70 ± 0.00 |

| Patients (n) | COWAT | MOCA | DSST | HVLT | TMT-A | TMT-B | BT-t | BT-AC | BT-AS | NHPT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LGG | 5 | −0.108 ± 0.664 | 1.04 ± 0.906 | 1.57 ± 1.25 | −0.17 ± 1.2 | 0.446 ± 0.433 | 0.45 ± 1.47 | 1.48 ± 0.622 | 0.446 ± 0.361 | 0.442 ± 0.592 | 0.59 ± 1.02 |

| HGG | 13 | 0.397 ± 1.54 | 0.356 ± 1.09 | 0.436 ± 2.08 | 0.08 ± 0.636 | 1.94 ± 1.88 | 1.89 ± 3.2 | 1.11 ± 1.54 | −1.91 ± 2.13 | −0.162 ± 1.88 | 1.44 ± 1.48 |

| p-value | 0.706 | 0.434 | 0.434 | 0.853 | 0.434 | 0.537 | 0.537 | 0.189 | 0.706 | 0.434 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schwendner, M.; Kram, L.; Lackner, J.; Zhang, H.; Krieg, S.M.; Ille, S. Assessment of Network Integrity in Right-Hemispheric Glioma Patients Using Function-Based Tractography and Domain-Specific Cognitive Testing. Cancers 2025, 17, 4007. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17244007

Schwendner M, Kram L, Lackner J, Zhang H, Krieg SM, Ille S. Assessment of Network Integrity in Right-Hemispheric Glioma Patients Using Function-Based Tractography and Domain-Specific Cognitive Testing. Cancers. 2025; 17(24):4007. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17244007

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchwendner, Maximilian, Leonie Kram, Johanna Lackner, Haosu Zhang, Sandro M. Krieg, and Sebastian Ille. 2025. "Assessment of Network Integrity in Right-Hemispheric Glioma Patients Using Function-Based Tractography and Domain-Specific Cognitive Testing" Cancers 17, no. 24: 4007. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17244007

APA StyleSchwendner, M., Kram, L., Lackner, J., Zhang, H., Krieg, S. M., & Ille, S. (2025). Assessment of Network Integrity in Right-Hemispheric Glioma Patients Using Function-Based Tractography and Domain-Specific Cognitive Testing. Cancers, 17(24), 4007. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17244007