Early Detection and Prevention of Ovarian Cancer

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Molecular Features, Pre-Cursor Lesions and Carcinogenesis

3. Traditional and Novel Detection Methods

3.1. Circulating Biomarkers and Cytology

3.1.1. Protein Biomarkers

3.1.2. Autoantibodies

3.1.3. MicroRNAs

3.1.4. Urine Testing

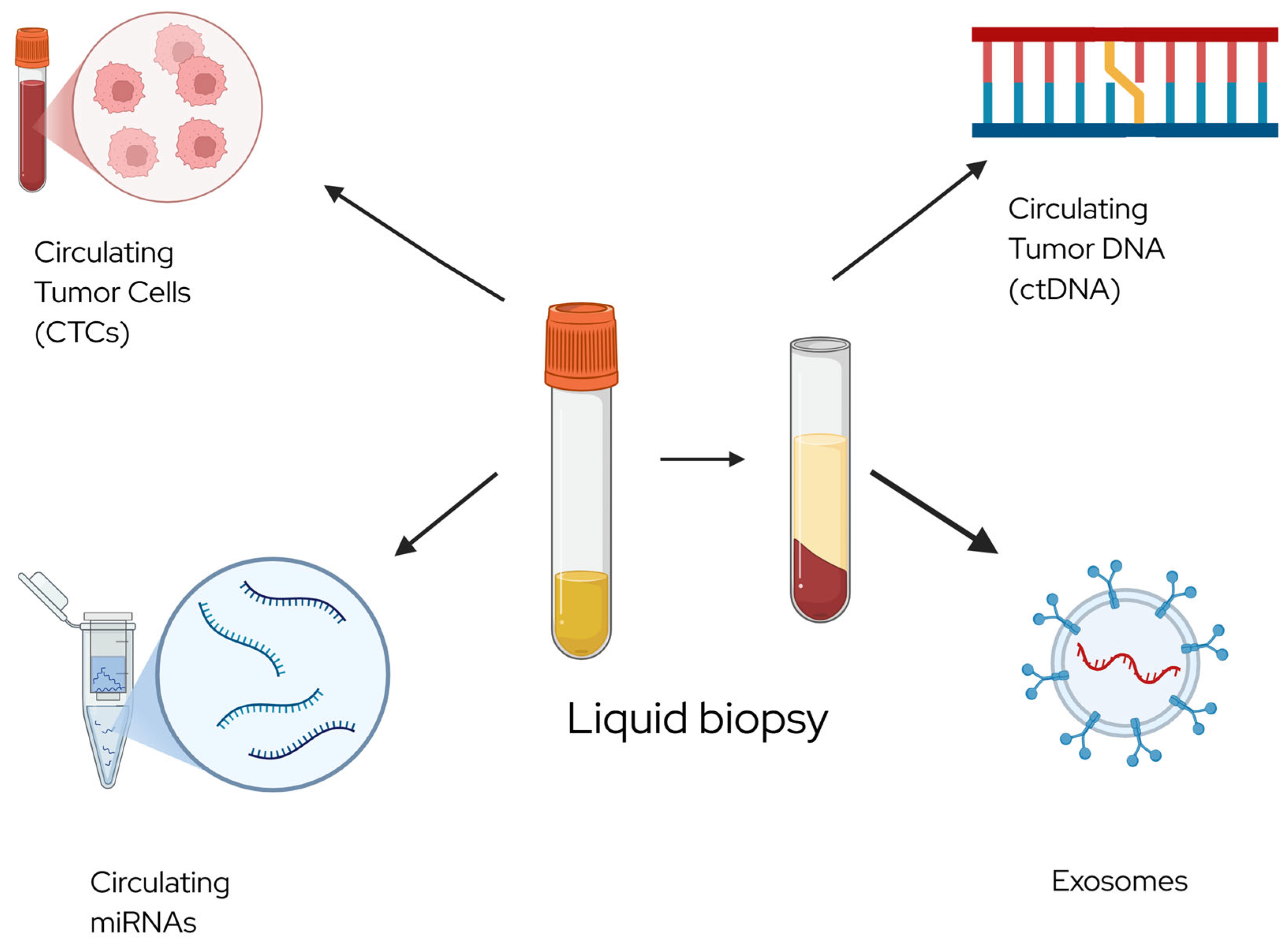

3.1.5. Circulating Tumor DNA

3.1.6. DNA Methylation

3.1.7. Microbiome

3.1.8. Fallopian Tube Cytology and Tumor DNA Detection in Pap Smears

3.2. Imaging

3.2.1. Ultrasound with Contrast

3.2.2. Magnetic Resonance Imaging

4. Novel Prevention Methods

4.1. Salpingectomy

4.2. Chemoprevention

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CA-125 | Carbohydrate Antigen 125 |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| EOC | Epithelial ovarian cancer |

| HE4 | Human epididymis protein 4 |

| HGSOC | High-grade serous ovarian cancer |

| HMGA | High mobility group A |

| IUD | Intrauterine device |

| MRA | Magnetic relaxometry |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| NSAID | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| STIC | Serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma |

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Fuchs, H.E.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goff, B.A.; Mandel, L.; Muntz, H.G.; Melancon, C.H. Ovarian carcinoma diagnosis. Cancer 2000, 89, 2068–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berek, J.S.; Renz, M.; Kehoe, S.; Kumar, L.; Friedlander, M. Cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum: 2021 update. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2021, 155, 61–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torre, L.A.; Trabert, B.; DeSantis, C.E.; Miller, K.D.; Samimi, G.; Runowicz, C.D.; Gaudet, M.M.; Jemal, A.; Siegel, R.L. Ovarian cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsopoulos, J.; Hathaway, C.A.; Narod, S.A.; Teras, L.R.; Patel, A.V.; Hu, C.; Yadav, S.; Couch, F.J.; Tworoger, S.S. Germline Mutations in 12 Genes and Risk of Ovarian Cancer in Three Population-Based Cohorts. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2023, 32, 1402–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinopoulos, P.A.; Norquist, B.; Lacchetti, C.; Armstrong, D.; Grisham, R.N.; Goodfellow, P.J.; Kohn, E.C.; Levine, D.A.; Liu, J.F.; Lu, K.H.; et al. Germline and Somatic Tumor Testing in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer: ASCO Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 1222–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, P.M.; Jordan, S.J. Epidemiology of epithelial ovarian cancer. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2017, 41, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roh, M.H.; Kindelberger, D.; Crum, C.P. Serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma and the dominant ovarian mass: Clues to serous tumor origin? Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2009, 33, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crum, C.P.; Drapkin, R.; Miron, A.; Ince, T.A.; Muto, M.; Kindelberger, D.W.; Lee, Y. The distal fallopian tube: A new model for pelvic serous carcinogenesis. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 19, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gockley, A.A.; Elias, K.M. Fallopian tube tumorigenesis and clinical implications for ovarian cancer risk-reduction. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2018, 69, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, W.C.; Weinberg, R.A. Rules for making human tumor cells. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347, 1593–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bast, R.C., Jr.; Xu, F.J.; Yu, Y.H.; Barnhill, S.; Zhang, Z.; Mills, G.B. CA 125: The past and the future. Int. J. Biol. Markers 1998, 13, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, E.L.; Hollingworth, J.; Reynolds, T.M. The role of CA125 in clinical practice. J. Clin. Pathol. 2005, 58, 308–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dochez, V.; Caillon, H.; Vaucel, E.; Dimet, J.; Winer, N.; Ducarme, G. Biomarkers and algorithms for diagnosis of ovarian cancer: CA125, HE4, RMI and ROMA, a review. J. Ovarian Res. 2019, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, G.; Weroha, S.J.; Cliby, W. Ovarian Cancer: A Review. JAMA 2025, 334, 1278–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.G.; Brown, A.K.; Miller, M.C.; Skates, S.; Allard, W.J.; Verch, T.; Steinhoff, M.; Messerlian, G.; DiSilvestro, P.; Granai, C.O.; et al. The use of multiple novel tumor biomarkers for the detection of ovarian carcinoma in patients with a pelvic mass. Gynecol. Oncol. 2008, 108, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, D.W.; Bast, R.C., Jr.; Berg, C.D.; Diamandis, E.P.; Godwin, A.K.; Hartge, P.; Lokshin, A.E.; Lu, K.H.; McIntosh, M.W.; Mor, G.; et al. Ovarian cancer biomarker performance in prostate, lung, colorectal, and ovarian cancer screening trial specimens. Cancer Prev. Res. 2011, 4, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, K.L.; Schock, H.; Fortner, R.T.; Hüsing, A.; Fichorova, R.N.; Yamamoto, H.S.; Vitonis, A.F.; Johnson, T.; Overvad, K.; Tjønneland, A.; et al. A Prospective Evaluation of Early Detection Biomarkers for Ovarian Cancer in the European EPIC Cohort. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 4664–4675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macdonald, I.K.; Parsy-Kowalska, C.B.; Chapman, C.J. Autoantibodies: Opportunities for Early Cancer Detection. Trends Cancer 2017, 3, 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erickson, B.K.; Kinde, I.; Dobbin, Z.C.; Wang, Y.; Martin, J.Y.; Alvarez, R.D.; Conner, M.G.; Huh, W.K.; Roden, R.B.S.; Kinzler, K.W.; et al. Detection of somatic TP53 mutations in tampons of patients with high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 124, 881–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.L.; Gentry-Maharaj, A.; Simmons, A.; Ryan, A.; Fourkala, E.O.; Lu, Z.; Baggerly, K.A.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, K.H.; Bowtell, D.; et al. Elevation of TP53 Autoantibody Before CA125 in Preclinical Invasive Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 5912–5922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurley, L.C.; Levin, N.K.; Chatterjee, M.; Coles, J.; Muszkat, S.; Howarth, Z.; Dyson, G.; Tainsky, M.A. Evaluation of paraneoplastic antigens reveals TRIM21 autoantibodies as biomarker for early detection of ovarian cancer in combination with autoantibodies to NY-ESO-1 and TP53. Cancer Biomark. 2020, 27, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortner, R.T.; Damms-Machado, A.; Kaaks, R. Systematic review: Tumor-associated antigen autoantibodies and ovarian cancer early detection. Gynecol. Oncol. 2017, 147, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokshin, A.E.; Winans, M.; Landsittel, D.; Marrangoni, A.M.; Velikokhatnaya, L.; Modugno, F.; Nolen, B.M.; Gorelik, E. Circulating IL-8 and anti-IL-8 autoantibody in patients with ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2006, 102, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliminejad, K.; Khorram Khorshid, H.R.; Soleymani Fard, S.; Ghaffari, S.H. An overview of microRNAs: Biology, functions, therapeutics, and analysis methods. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 5451–5465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, C.W.; Hahn, M.A.; Gard, G.B.; Maidens, J.; Huh, J.Y.; Marsh, D.J.; Howell, V.M. Elevated levels of circulating microRNA-200 family members correlate with serous epithelial ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer 2012, 12, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafouri-Fard, S.; Shoorei, H.; Taheri, M. miRNA profile in ovarian cancer. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2020, 113, 104381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoi, A.; Yoshioka, Y.; Hirakawa, A.; Yamamoto, Y.; Ishikawa, M.; Ikeda, S.I.; Kato, T.; Niimi, K.; Kajiyama, H.; Kikkawa, F.; et al. A combination of circulating miRNAs for the early detection of ovarian cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 89811–89823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, D.; Song, F.; Wen, Y.; Hao, Q.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Chen, K. Plasma miRNAs as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for ovarian cancer. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e77853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Pan, W.; Jin, Y.; Zheng, J. MiR-25 promotes ovarian cancer proliferation and motility by targeting LATS2. Tumour Biol. 2014, 35, 12339–12344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Wu, W.; Claret, F.X. Mutual regulation of microRNAs and DNA methylation in human cancers. Epigenetics 2017, 12, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambers, A.F.; Vanderhyden, B.C. Ovarian cancer biomarkers in urine. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rani, S.; Sehgal, A.; Kaur, J.; Pandher, D.K.; Punia, R.S. Osteopontin as a Tumor Marker in Ovarian Cancer. J. Midlife Health 2022, 13, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, M.M.; Deng, J.; Cheng, X.L.; Yan, Z.; Li, Q.C.; Xing, Y.Y.; Fan, D.M.; Tian, X.Y. Diagnostic accuracy of urine HE4 in patients with ovarian cancer: A meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 9660–9671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Xie, M.; He, H.; Shi, Y.; Luo, B.; Gong, G.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Wu, X.; Wen, J. Increases urinary HMGA1 in serous epithelial ovarian cancer patients. Cancer Biomark. 2015, 15, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Su, L.; Qian, C. Circulating tumor DNA: A promising biomarker in the liquid biopsy of cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 48832–48841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantel, K.; Alix-Panabières, C. Liquid biopsy and minimal residual disease—Latest advances and implications for cure. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 16, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettegowda, C.; Sausen, M.; Leary, R.J.; Kinde, I.; Wang, Y.; Agrawal, N.; Bartlett, B.R.; Wang, H.; Luber, B.; Alani, R.M.; et al. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 224ra24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forshew, T.; Murtaza, M.; Parkinson, C.; Gale, D.; Tsui, D.W.; Kaper, F.; Dawson, S.J.; Piskorz, A.M.; Jimenez-Linan, M.; Bentley, D.; et al. Noninvasive identification and monitoring of cancer mutations by targeted deep sequencing of plasma DNA. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 136ra68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.D.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Thoburn, C.; Afsari, B.; Danilova, L.; Douville, C.; Javed, A.A.; Wong, F.; Mattox, A.; et al. Detection and localization of surgically resectable cancers with a multi-analyte blood test. Science 2018, 359, 926–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhou, N.; Liu, J. Ovarian Cancer Diagnosis and Prognosis Based on Cell-Free DNA Methylation. Cancer Control 2024, 31, 10732748241255548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widschwendter, M.; Zikan, M.; Wahl, B.; Lempiäinen, H.; Paprotka, T.; Evans, I.; Jones, A.; Ghazali, S.; Reisel, D.; Eichner, J.; et al. The potential of circulating tumor DNA methylation analysis for the early detection and management of ovarian cancer. Genome Med. 2017, 9, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papakonstantinou, E.; Androutsopoulos, G.; Logotheti, S.; Adonakis, G.; Maroulis, I.; Tzelepi, V. DNA Methylation in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer: Current Data and Future Perspectives. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 2021, 14, 1013–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łaniewski, P.; Ilhan, Z.E.; Herbst-Kralovetz, M.M. The microbiome and gynaecological cancer development, prevention and therapy. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2020, 17, 232–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, R.; Makhlouf, Z.; Alharbi, A.M.; Alfahemi, H.; Khan, N.A. The Gut Microbiome and Female Health. Biology 2022, 11, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipos, A.; Ujlaki, G.; Mikó, E.; Maka, E.; Szabó, J.; Uray, K.; Krasznai, Z.; Bai, P. The role of the microbiome in ovarian cancer: Mechanistic insights into oncobiosis and to bacterial metabolite signaling. Mol. Med. 2021, 27, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lum, D.; Guido, R.; Rodriguez, E.; Lee, T.; Mansuria, S.; D’Ambrosio, L.; Austin, R.M. Brush cytology of the fallopian tube and implications in ovarian cancer screening. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2014, 21, 851–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maritschnegg, E.; Wang, Y.; Pecha, N.; Horvat, R.; Van Nieuwenhuysen, E.; Vergote, I.; Heitz, F.; Sehouli, J.; Kinde, I.; Diaz, L.A., Jr.; et al. Lavage of the Uterine Cavity for Molecular Detection of Müllerian Duct Carcinomas: A Proof-of-Concept Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 4293–4300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Klein, R.; Arnold, S.; Chambers, S.; Zheng, W. Cytologic studies of the fallopian tube in patients undergoing salpingo-oophorectomy. Cancer Cell Int. 2016, 16, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, I.; Kameda, S.; Hoshi, K. Early detection of ovarian and fallopian tube cancer by examination of cytological samples from the endometrial cavity. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 109, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, E.F.; Lum, D.; Guido, R.; Austin, R.M. Cytologic findings in experimental in vivo fallopian tube brush specimens. Acta Cytol. 2013, 57, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Douville, C.; Cohen, J.D.; Yen, T.T.; Kinde, I.; Sundfelt, K.; Kjær, S.K.; Hruban, R.H.; Shih, I.M.; et al. Evaluation of liquid from the Papanicolaou test and other liquid biopsies for the detection of endometrial and ovarian cancers. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018, 10, eaap8793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinde, I.; Bettegowda, C.; Wang, Y.; Wu, J.; Agrawal, N.; Shih Ie, M.; Kurman, R.; Dao, F.; Levine, D.A.; Giuntoli, R.; et al. Evaluation of DNA from the Papanicolaou test to detect ovarian and endometrial cancers. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013, 5, 167ra4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba, S.; Yu, M. Ultrasound-stimulated microbubbles enhances radiosensitivity of ovarian cancer. Acta Radiol. 2022, 63, 1433–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmann, J.K.; Bonomo, L.; Testa, A.C.; Rinaldi, P.; Rindi, G.; Valluru, K.S.; Petrone, G.; Martini, M.; Lutz, A.M.; Gambhir, S.S. Ultrasound Molecular Imaging with BR55 in Patients with Breast and Ovarian Lesions: First-in-Human Results. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 2133–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; Sun, J.; Zhu, S.; He, J.; Hao, L.; Xiao, L.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Pan, X.; Wang, Z.; et al. Ultrasound-mediated destruction of oxygen and paclitaxel loaded dual-targeting microbubbles for intraperitoneal treatment of ovarian cancer xenografts. Cancer Lett. 2017, 391, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nebgen, D.R.; Lu, K.H.; Bast, R.C., Jr. Novel Approaches to Ovarian Cancer Screening. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 21, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandsburger, M.H.; Radoul, M.; Addadi, Y.; Mpofu, S.; Cohen, B.; Eilam, R.; Neeman, M. Ovarian carcinoma: Quantitative biexponential MR imaging relaxometry reveals the dynamic recruitment of ferritin-expressing fibroblasts to the angiogenic rim of tumors. Radiology 2013, 268, 790–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsubara, S.; Kawahara, N.; Horie, A.; Murakami, R.; Horikawa, N.; Sumida, D.; Wada, T.; Maehana, T.; Yamawaki, A.; Ichikawa, M.; et al. Magnetic resonance relaxometry improves the accuracy of conventional MRI in the diagnosis of endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer: A case report. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 11, 296–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawahara, N.; Kobayashi, H.; Maehana, T.; Iwai, K.; Yamada, Y.; Kawaguchi, R.; Takahama, J.; Marugami, N.; Nishi, H.; Sakai, Y.; et al. MR Relaxometry for Discriminating Malignant Ovarian Cystic Tumors: A Prospective Multicenter Cohort Study. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, F.G.; Pavlik, E.J. Perspectives on Ovarian Cancer 1809 to 2022 and Beyond. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufin, K.G.A.; do Valle, H.A.; McAlpine, J.N.; Elwood, C.; Hanley, G.E. Complications after opportunistic salpingectomy compared with tubal ligation at cesarean section: A retrospective cohort study. Fertil. Steril. 2024, 121, 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagar, M.K.; Forlines, G.L.; Moellman, N.; Carlson, A.; Matthews, M.; Williams, M. Postpartum Opportunistic Salpingectomy Compared with Bilateral Tubal Ligation After Vaginal Delivery for Ovarian Cancer Risk Reduction: A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 141, 819–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagar, M.K.; Godecker, A.; Landeros, M.V.; Williams, M. Postpartum Salpingectomy Compared with Standard Tubal Ligation After Vaginal Delivery. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 137, 514–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, E.; Strandell, A.; Granåsen, G.; Idahl, A. Menopausal symptoms and surgical complications after opportunistic bilateral salpingectomy, a register-based cohort study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 220, 85.e1–85.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, C.; Chenoy, R.; Chandrasekaran, D.; Brockbank, E.; Hollingworth, A.; Vimplis, S.; Lawrence, A.C.; Jeyarajah, A.R.; Oram, D.; Deo, N.; et al. Persistence of fimbrial tissue on the ovarian surface after salpingectomy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 217, 425.e416–425.e421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenbeek, M.P.; van Bommel, M.H.D.; intHout, J.; Peterson, C.B.; Simons, M.; Roes, K.C.B.; Kets, M.; Norquist, B.M.; Swisher, E.M.; Hermens, R.; et al. TUBectomy with delayed oophorectomy as an alternative to risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in high-risk women to assess the safety of prevention: The TUBA-WISP II study protocol. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2023, 33, 982–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, W.K.; Pugh, S.L.; Walker, J.L.; Pennington, K.; Jewell, E.L.; Havrilesky, L.J.; Carter, J.; Muller, C.; Drapkin, R.; Lankes, H.A. NRG-CC008: A nonrandomized prospective clinical trial comparing the non-inferiority of salpingectomy to salpingo-oophorectomy to reduce the risk of ovarian cancer among BRCA1 carriers [SOROCk]. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaba, F.; Robbani, S.; Singh, N.; McCluggage, W.G.; Wilkinson, N.; Ganesan, R.; Bryson, G.; Rowlands, G.; Tyson, C.; Arora, R.; et al. Preventing Ovarian Cancer through early Excision of Tubes and late Ovarian Removal (PROTECTOR): Protocol for a prospective non-randomised multi-center trial. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2021, 31, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falconer, H.; Yin, L.; Grönberg, H.; Altman, D. Ovarian cancer risk after salpingectomy: A nationwide population-based study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2015, 107, dju410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guldberg, R.; Wehberg, S.; Skovlund, C.W.; Mogensen, O.; Lidegaard, O. Salpingectomy as standard at hysterectomy? A Danish cohort study, 1977–2010. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e002845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idahl, A.; Darelius, A.; Sundfeldt, K.; Pålsson, M.; Strandell, A. Hysterectomy and opportunistic salpingectomy (HOPPSA): Study protocol for a register-based randomized controlled trial. Trials 2019, 20, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimdal, K.; Skovlund, E.; Møller, P. Oral contraceptives and risk of familial breast cancer. Cancer Detect. Prev. 2002, 26, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahanfar, S.; Mortazavi, J.; Lapidow, A.; Cu, C.; Al Abosy, J.; Morris, K.; Becerra-Mateus, J.C.; Steinfeldt, M.; Maurer, O.; Bohang, J.; et al. Assessing the impact of contraceptive use on reproductive cancer risk among women of reproductive age-a systematic review. Front. Glob. Womens Health 2024, 5, 1487820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beral, V.; Doll, R.; Hermon, C.; Peto, R.; Reeves, G. Ovarian cancer and oral contraceptives: Collaborative reanalysis of data from 45 epidemiological studies including 23,257 women with ovarian cancer and 87,303 controls. Lancet 2008, 371, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, L.J.; Desanto, K.; Teal, S.B.; Sheeder, J.; Guntupalli, S.R. Intrauterine Device Use and Ovarian Cancer Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 134, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Bai, B.; Xi, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhao, Y. Is aspirin use associated with a decreased risk of ovarian cancer? A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies with dose-response analysis. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 142, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trabert, B.; Poole, E.M.; White, E.; Visvanathan, K.; Adami, H.O.; Anderson, G.L.; Brasky, T.M.; Brinton, L.A.; Fortner, R.T.; Gaudet, M.; et al. Analgesic Use and Ovarian Cancer Risk: An Analysis in the Ovarian Cancer Cohort Consortium. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2019, 111, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurwitz, L.M.; Webb, P.M.; Jordan, S.J.; Doherty, J.A.; Harris, H.R.; Goodman, M.T.; Shvetsov, Y.B.; Modugno, F.; Moysich, K.B.; Schildkraut, J.M.; et al. Association of Frequent Aspirin Use with Ovarian Cancer Risk According to Genetic Susceptibility. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e230666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabert, B.; Ness, R.B.; Lo-Ciganic, W.H.; Murphy, M.A.; Goode, E.L.; Poole, E.M.; Brinton, L.A.; Webb, P.M.; Nagle, C.M.; Jordan, S.J.; et al. Aspirin, nonaspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, and acetaminophen use and risk of invasive epithelial ovarian cancer: A pooled analysis in the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014, 106, djt431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burn, J.; Sheth, H.; Elliott, F.; Reed, L.; Macrae, F.; Mecklin, J.P.; Möslein, G.; McRonald, F.E.; Bertario, L.; Evans, D.G.; et al. Cancer prevention with aspirin in hereditary colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome), 10-year follow-up and registry-based 20-year data in the CAPP2 study: A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2020, 395, 1855–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moysich, K.B.; Mettlin, C.; Piver, M.S.; Natarajan, N.; Menezes, R.J.; Swede, H. Regular use of analgesic drugs and ovarian cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2001, 10, 903–906. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, C.R.; Schmitz, S.; Jick, H. Association between acetaminophen or nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and risk of developing ovarian, breast, or colon cancer. Pharmacotherapy 2002, 22, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasamoto, N.; Babic, A.; Vitonis, A.F.; Titus, L.; Cramer, D.W.; Trabert, B.; Tworoger, S.S.; Terry, K.L. Common Analgesic Use for Menstrual Pain and Ovarian Cancer Risk. Cancer Prev. Res. 2021, 14, 795–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gor, R.; Ramachandran, I.; Ramalingam, S. Targeting the Cancer Stem Cells in Endocrine Cancers with Phytochemicals. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2022, 22, 2589–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, S.C.; Amedei, A.; Aquilano, K.; Azmi, A.S.; Benencia, F.; Bhakta, D.; Bilsland, A.E.; Boosani, C.S.; Chen, S.; Ciriolo, M.R.; et al. Cancer prevention and therapy through the modulation of the tumor microenvironment. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2015, 35, S199–S223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milani, A.; Basirnejad, M.; Shahbazi, S.; Bolhassani, A. Carotenoids: Biochemistry, pharmacology and treatment. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 1290–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.L.; Deng, S.L.; Lian, Z.X.; Yu, K. Resveratrol Targets a Variety of Oncogenic and Oncosuppressive Signaling for Ovarian Cancer Prevention and Treatment. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, H.J.; Suh, D.S.; Moon, S.H.; Song, Y.J.; Yoon, M.S.; Park, D.Y.; Choi, K.U.; Kim, Y.K.; Kim, K.H. Silibinin inhibits tumor growth through downregulation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase and Akt in vitro and in vivo in human ovarian cancer cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 4089–4096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronesi, U.; Decensi, A. Retinoids for ovarian cancer prevention: Laboratory data set the stage for thoughtful clinical trials. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2001, 93, 486–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapur, A.; Mehta, P.; Simmons, A.D.; Ericksen, S.S.; Mehta, G.; Palecek, S.P.; Felder, M.; Stenerson, Z.; Nayak, A.; Dominguez, J.M.A.; et al. Atovaquone: An Inhibitor of Oxidative Phosphorylation as Studied in Gynecologic Cancers. Cancers 2022, 14, 2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Montemorano, L.; Huffman, L.; Barroilhet, L. Early Detection and Prevention of Ovarian Cancer. Cancers 2025, 17, 4006. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17244006

Montemorano L, Huffman L, Barroilhet L. Early Detection and Prevention of Ovarian Cancer. Cancers. 2025; 17(24):4006. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17244006

Chicago/Turabian StyleMontemorano, Lauren, Laura Huffman, and Lisa Barroilhet. 2025. "Early Detection and Prevention of Ovarian Cancer" Cancers 17, no. 24: 4006. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17244006

APA StyleMontemorano, L., Huffman, L., & Barroilhet, L. (2025). Early Detection and Prevention of Ovarian Cancer. Cancers, 17(24), 4006. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17244006