Rapid Hematological and Molecular Response to Pegylated Interferon in WHO-Defined Pre-Fibrotic Myelofibrosis

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Methods

2.3. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Patient and Disease Characteristics at Diagnosis

3.2. Patient and Disease Characteristics at the Interferon Treatment Starting Time

3.3. Treatment Duration

3.4. Hematological Response

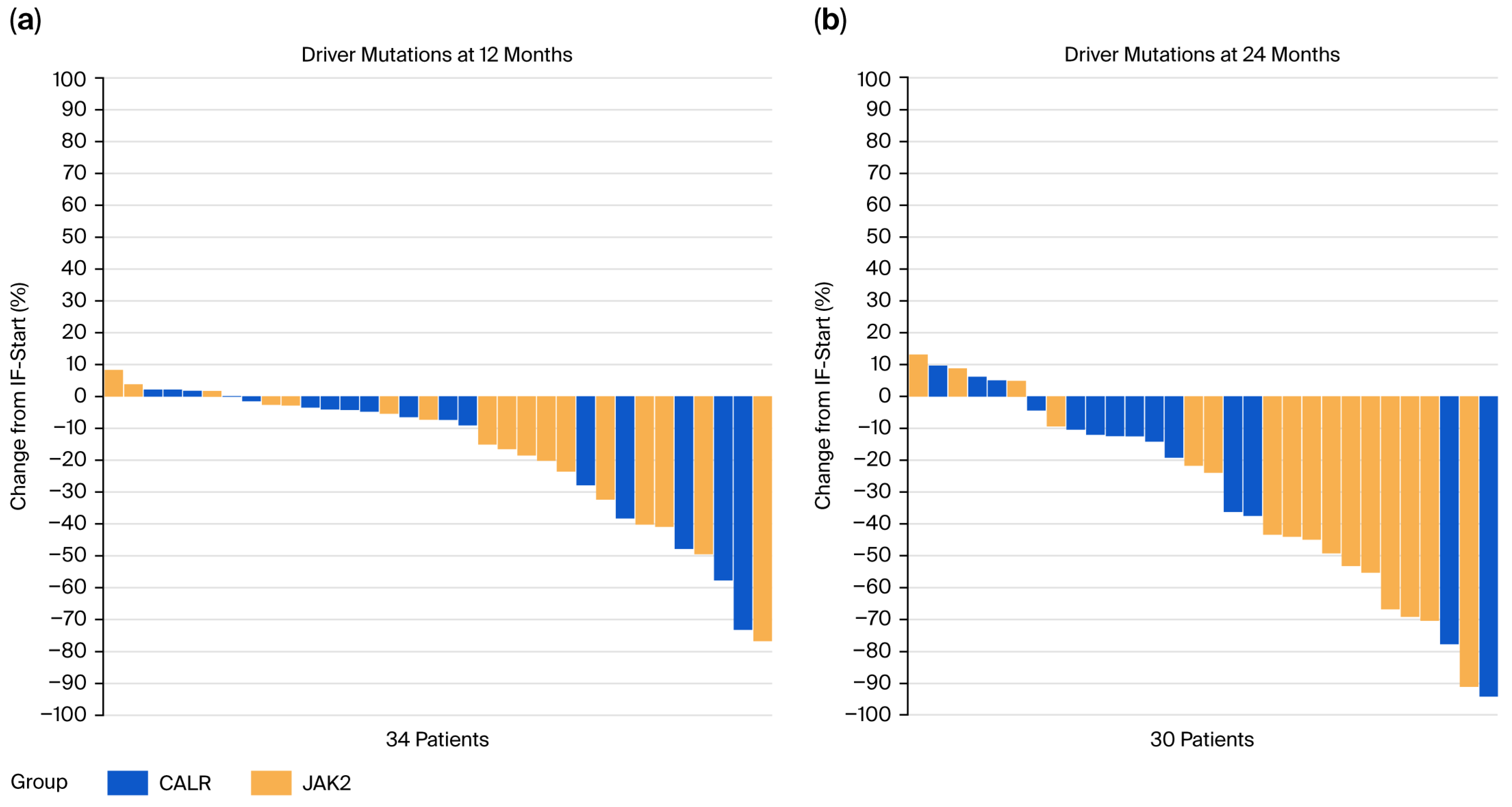

3.5. Molecular Response

3.6. Spleen Response

3.7. Follow-Up Bone Marrow Investigations

3.8. Univariate and Multivariate Analyses with Respect to Hematological Response

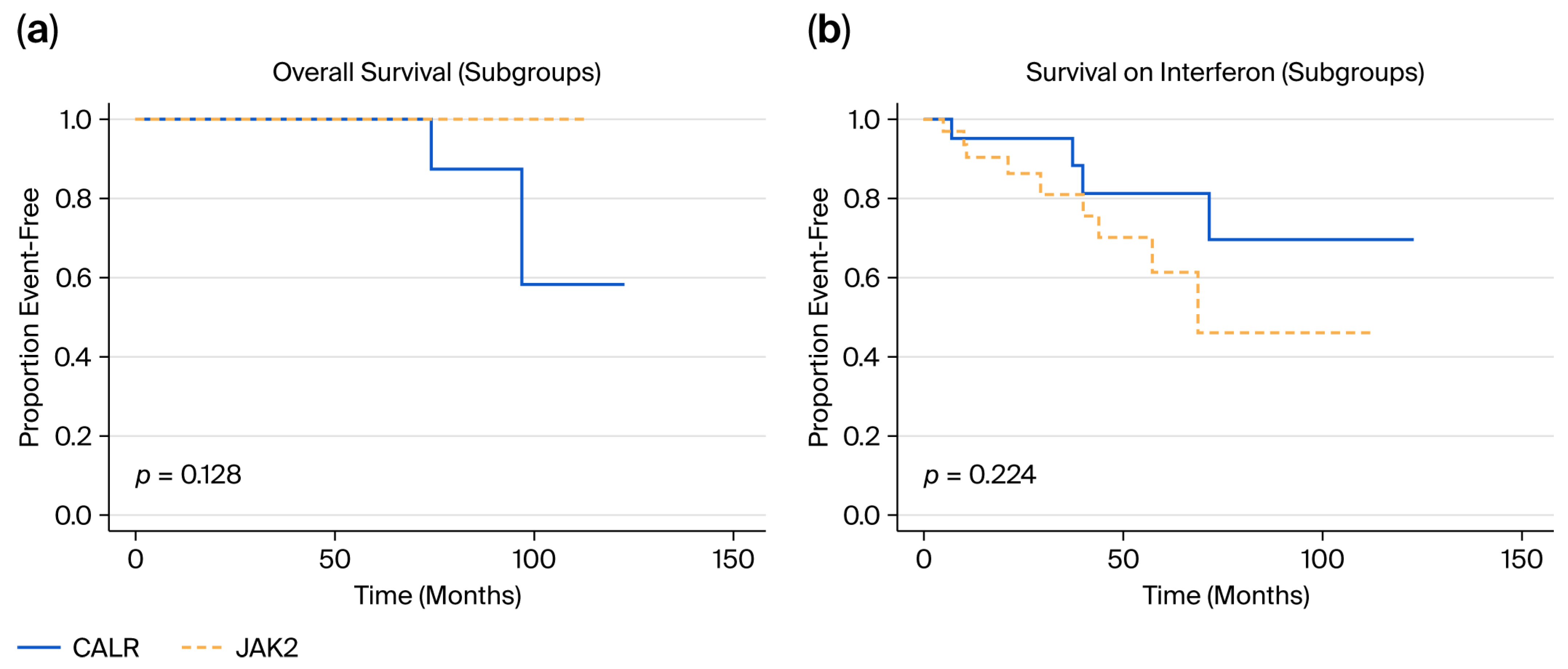

3.9. Event Rates and Survival Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vainchenker, W.; Kralovics, R. Genetic basis and molecular pathophysiology of classical myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood 2017, 129, 667–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, J.; Kvasnicka, H.M. Chronic myeloproliferative disorders. The new WHO classification. Pathologe 2001, 22, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arber, D.A.; Orazi, A.; Hasserjian, R.; Thiele, J.; Borowitz, M.J.; Le Beau, M.M.; Bloomfield, C.D.; Cazzola, M.; Vardiman, J.W. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood 2016, 127, 2391–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoury, J.D.; Solary, E.; Abla, O.; Akkari, Y.; Alaggio, R.; Apperley, J.F.; Bejar, R.; Berti, E.; Busque, L.; Chan, J.K.C.; et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Myeloid and Histiocytic/Dendritic Neoplasms. Leukemia 2022, 36, 1703–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guglielmelli, P.; Pacilli, A.; Rotunno, G.; Rumi, E.; Rosti, V.; Delaini, F.; Maffioli, M.; Fanelli, T.; Pancrazzi, A.; Pietra, D.; et al. Presentation and outcome of patients with 2016 WHO diagnosis of prefibrotic and overt primary myelofibrosis. Blood 2017, 129, 3227–3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buxhofer-Ausch, V.; Gisslinger, B.; Schalling, M.; Gleiss, A.; Schiefer, A.; Müllauer, L.; Thiele, J.; Kralovics, R.; Gisslinger, H. Impact of white blood cell counts at diagnosis and during follow-up in patients with essential thrombocythaemia and prefibrotic primary myelofibrosis. Br. J. Haematol. 2016, 179, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissler, K.; Jäger, E.; Gisslinger, B.; Thiele, J.; Schwarzinger, I.; Gisslinger, H. Circulating hematopoietic progenitor cells in essential thrombocythemia versus prefibrotic/early primary myelofibrosis. Am. J. Hematol. 2014, 89, 1157–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, J.; Kvasnicka, H.M.; Müllauer, L.; Buxhofer-Ausch, V.; Gisslinger, B.; Gisslinger, H. Essential thrombocythemia versus early primary myelofibrosis: A multicenter study to validate the WHO classification. Blood 2011, 117, 5710–5718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalling, M.; Gleiss, A.; Gisslinger, B.; Wölfler, A.; Buxhofer-Ausch, V.; Jeryczynski, G.; Krauth, M.-T.; Simonitsch-Klupp, I.; Beham-Schmid, C.; Thiele, J.; et al. Essential thrombocythemia vs. pre-fibrotic/early primary myelofibrosis: Discrimination by laboratory and clinical data. Blood Cancer J. 2017, 7, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbui, T.; Thiele, J.; Gisslinger, H.; Kvasnicka, H.M.; Vannucchi, A.M.; Guglielmelli, P.; Orazi, A.; Tefferi, A. The 2016 WHO classification and diagnostic criteria for myeloproliferative neoplasms: Document summary and in-depth discussion. Blood Cancer J. 2018, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbui, T.; Thiele, J.; Carobbio, A.; Passamonti, F.; Rumi, E.; Randi, M.L.; Bertozzi, I.; Vannucchi, A.M.; Gisslinger, H.; Gisslinger, B.; et al. Disease characteristics and clinical outcome in young adults with essential thrombocythemia versus early/prefibrotic primary myelofibrosis. Blood 2012, 120, 569–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gisslinger, H.; Jeryczynski, G.; Gisslinger, B.; Wölfler, A.; Burgstaller, S.; Buxhofer-Ausch, V.; Schalling, M.; Krauth, M.-T.; Schiefer, A.-I.; Kornauth, C.; et al. Clinical impact of bone marrow morphology for the diagnosis of essential thrombocythemia: Comparison between the BCSH and the WHO criteria. Leukemia 2015, 30, 1126–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbui, T.; Thiele, J.; Gisslinger, H.; Finazzi, G.; Vannucchi, A.; Tefferi, A. The 2016 revision of WHO classification of myeloproliferative neoplasms: Clinical and molecular advances. Blood Rev. 2016, 30, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiele, J.; Orazi, A.; Kvasnicka, H.M.; Franco, V.; Boveri, E.; Gianelli, U.; Gisslinger, H.; Passamonti, F.; Tefferi, A.; Barbui, T. European Bone Marrow Working Group trial on reproducibility of World Health Organization criteria to discriminate essential thrombocythemia from prefibrotic primary myelofibrosis. Haematologica 2012, 97, 360–365—Comment. Haematologica 2012, 97, e5–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbui, T.; Thiele, J.; Passamonti, F.; Rumi, E.; Boveri, E.; Ruggeri, M.; Rodeghiero, F.; D'Amore, E.S.; Randi, M.L.; Bertozzi, I.; et al. Survival and Disease Progression in Essential Thrombocythemia Are Significantly Influenced by Accurate Morphologic Diagnosis: An International Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 3179–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasselbalch, H.C.; Silver, R.T. New Perspectives of Interferon-alpha2 and Inflammation in Treating Philadelphia-negative Chronic Myeloproliferative Neoplasms. HemaSphere 2021, 5, e645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasselbalch, H.C.; Bjørn, M.E. MPNs as Inflammatory Diseases: The Evidence, Consequences, and Perspectives. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 102476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koschmieder, S.; Chatain, N. Role of inflammation in the biology of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood Rev. 2020, 42, 100711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasselbalch, H.C. Chronic inflammation as a promotor of mutagenesis in essential thrombocythemia, polycythemia vera and myelofibrosis. A human inflammation model for cancer development? Leuk. Res. 2013, 37, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buxhofer-Ausch, V.; Gisslinger, H.; Thiele, J.; Gisslinger, B.; Kvasnicka, H.; Müllauer, L.; Frantal, S.; Carobbio, A.; Passamonti, F.; Rumi, E.; et al. Leukocytosis as an important risk factor for arterial thrombosis in WHO-defined early/prefibrotic myelofibrosis: An international study of 264 patients. Am. J. Hematol. 2012, 87, 669–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finazzi, G.; Carobbio, A.; Thiele, J.; Passamonti, F.; Rumi, E.; Ruggeri, M.; Rodeghiero, F.; Randi, M.L.; Bertozzi, I.; Vannucchi, A.M.; et al. Incidence and risk factors for bleeding in 1104 patients with essential thrombocythemia or prefibrotic myelofibrosis diagnosed according to the 2008 WHO criteria. Leukemia 2011, 26, 716–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbui, T.; Thiele, J.; Gisslinger, H.; Orazi, A.; Vannucchi, A.M.; Gianelli, U.; Beham-Schmid, C.; Tefferi, A. Comments on pre-fibrotic myelofibrosis and how should it be managed. Br. J. Haematol. 2019, 186, 358–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griesshammer, M.; Al-Ali, H.K.; Eckardt, J.-N.; Fiegl, M.; Göthert, J.; Jentsch-Ullrich, K.; Koschmieder, S.; Kvasnicka, H.M.; Reiter, A.; Schmidt, B.; et al. How I diagnose and treat patients in the pre-fibrotic phase of primary myelofibrosis (pre-PMF)—Practical approaches of a German expert panel discussion in 2024. Ann. Hematol. 2025, 104, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koschmieder, S. Novel approaches in myelofibrosis. HemaSphere 2024, 8, e70056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tefferi, A. Primary myelofibrosis: 2023 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am. J. Hematol. 2023, 98, 801–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finazzi, G.; Vannucchi, A.M.; Barbui, T. Prefibrotic myelofibrosis: Treatment algorithm 2018. Blood Cancer J. 2018, 8, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewersdorf, J.P.; Giri, S.; Wang, R.; Podoltsev, N.; Williams, R.T.; Rampal, R.K.; Tallman, M.S.; Zeidan, A.M.; Stahl, M. Interferon Therapy in Myelofibrosis: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020, 20, e712–e723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koschmieder, S.; I Mughal, T.; Hasselbalch, H.C.; Barosi, G.; Valent, P.; Kiladjian, J.-J.; Jeryczynski, G.; Gisslinger, H.; Jutzi, J.S.; Pahl, H.L.; et al. Myeloproliferative neoplasms and inflammation: Whether to target the malignant clone or the inflammatory process or both. Leukemia 2016, 30, 1018–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massarenti, L.; Knudsen, T.A.; Enevold, C.; Skov, V.; Kjær, L.; Larsen, M.K.; Larsen, T.S.; Hansen, D.L.; Hasselbalch, H.C.; Nielsen, C.H. Interferon alpha-2 treatment reduces circulating neutrophil extracellular trap levels in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Br. J. Haematol. 2023, 202, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, R.K.; Andersen, M.; Knudsen, T.A.; Sajid, Z.; Gudmand-Hoeyer, J.; Dam, M.J.B.; Skov, V.; Kjær, L.; Ellervik, C.; Larsen, T.S.; et al. Data-driven analysis of JAK2V617F kinetics during interferon-alpha2 treatment of patients with polycythemia vera and related neoplasms. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 2039–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skov, V.; Riley, C.H.; Thomassen, M.; Kjær, L.; Larsen, T.S.; Bjerrum, O.W.; A Kruse, T.; Hasselbalch, H.C. The impact of interferon-alpha2 on HLA genes in patients with polycythemia vera and related neoplasms. Leuk. Lymphoma 2016, 58, 1914–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rank, C.U.; Bjerrum, O.W.; Larsen, T.S.; Kjær, L.; de Stricker, K.; Riley, C.H.; Hasselbalch, H.C. Minimal residual disease after long-term interferon-alpha2 treatment: A report on hematological, molecular and histomorphological response patterns in 10 patients with essential thrombocythemia and polycythemia vera. Leuk. Lymphoma 2015, 57, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, C.H.; Hansen, M.; Brimnes, M.K.; Hasselbalch, H.C.; Bjerrum, O.W.; Straten, P.T.; Svane, I.M.; Jensen, M.K. Expansion of circulating CD56bright natural killer cells in patients with JAK2-positive chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms during treatment with interferon-α. Eur. J. Haematol. 2015, 94, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, T.S.; Iversen, K.F.; Hansen, E.; Mathiasen, A.B.; Marcher, C.; Frederiksen, M.; Larsen, H.; Helleberg, I.; Riley, C.H.; Bjerrum, O.W.; et al. Long term molecular responses in a cohort of Danish patients with essential thrombocythemia, polycythemia vera and myelofibrosis treated with recombinant interferon alpha. Leuk. Res. 2013, 37, 1041–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, R.T.; Kiladjian, J.-J.; Hasselbalch, H.C. Interferon and the treatment of polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia and myelofibrosis. Expert Rev. Hematol. 2013, 6, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skov, V.; Thomassen, M.; Kjær, L.; Ellervik, C.; Larsen, M.K.; Knudsen, T.A.; Kruse, T.A.; Hasselbalch, H.C. Interferon-alpha2 treatment of patients with polycythemia vera and related neoplasms favorably impacts deregulation of oxidative stress genes and antioxidative defense mechanisms. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquier, F.; Pegliasco, J.; Martin, J.-E.; Marti, S.; Plo, I. New approaches to standard of care in early-phase myeloproliferative neoplasms: Can interferon-α alter the natural history of the disease? Haematologica 2024, 110, 850–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’nEill, C.; Siddiqi, I.; Brynes, R.K.; Vergara-Lluri, M.; Moschiano, E.; O’cOnnell, C. Pegylated interferon for the treatment of early myelofibrosis: Correlation of serial laboratory studies with response to therapy. Ann. Hematol. 2016, 95, 733–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, R.T.; Barel, A.; Lascu, E.; Ritchie, E.K.; Roboz, G.J.; Christos, P.; Orazi, A.; Hassane, D.C.; Tam, W.; Cross, N.C. The Effect of Initial Molecular Profile on Response to Recombinant Interferon Alpha (rIFNα) Treatment in Early Myelofibrosis. Cancer 2017, 123, 2680–2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, R.T.; Vandris, K.; Goldman, J.J. Recombinant interferon-α may retard progression of early primary myelofibrosis: A preliminary report. Blood 2011, 117, 6669–6672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, T.A.; Skov, V.; Stevenson, K.E.; Werner, L.; Duke, W.; Laurore, C.; Gibson, C.J.; Nag, A.; Thorner, A.R.; Wollison, B.; et al. Genomic profiling of a randomized trial of interferon-α vs hydroxyurea in MPN reveals mutation-specific responses. Blood Adv. 2022, 6, 2107–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, H.; Au, L.; Yim, R.; Lee, P.; Li, V.; Chin, L.; Zhang, Q.; Chan, P.-Y.; Au, C.-K.; Wu, T.; et al. Ropeginterferon alfa-2b for pre-fibrotic primary myelofibrosis and DIPSS low/intermediate-risk myelofibrosis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 6573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianotto, J.-C.; Chauveau, A.; Boyer-Perrard, F.; Gyan, E.; Laribi, K.; Cony-Makhoul, P.; Demory, J.-L.; de Renzis, B.; Dosquet, C.; Rey, J.; et al. Benefits and pitfalls of pegylated interferon-α2a therapy in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasm-associated myelofibrosis: A French Intergroup of Myeloproliferative neoplasms (FIM) study. Haematologica 2017, 103, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, H.; Au, L.; Leung, G.M.K.; Tsai, D.; Yim, R.; Chin, L.; Li, V.; Lee, P.; Sin, A.C.F.; Hou, H.A.; et al. Ropeginterferon Alfa-2b for Pre-Fibrotic Primary Myelofibrosis and DIPSS Low/Intermediate-1 Risk Myelofibrosis: Durable Responses and Evidence of Disease Modification. Blood 2023, 142, 4562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dam, M.J.B.; Pedersen, R.K.; Knudsen, T.A.; Andersen, M.; Ellervik, C.; Larsen, M.K.; Kjær, L.; Skov, V.; Hasselbalch, H.C.; Ottesen, J.T. A novel integrated biomarker index for the assessment of hematological responses in MPNs during treatment with hydroxyurea and interferon-alpha2. Cancer Med. 2022, 12, 4218–4226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasselbalch, H.C. Molecular profiling as a novel tool to predict response to interferon-α2 in MPNs: The proof of concept in early myelofibrosis. Cancer 2017, 123, 2600–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianotto, J.C.; Boyer-Perrard, F.; Gyan, E.; Laribi, K.; Cony-Makhoul, P.; Demory, J.L.; De Renzis, B.; Dosquet, C.; Rey, J.; Roy, L.; et al. Efficacy and safety of pegylat-ed-interferon alpha-2a in myelofibrosis: A study by the FIM and GEM French cooperative groups. Br. J. Haematol. 2013, 162, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbui, T.; Finazzi, G.; Carobbio, A.; Thiele, J.; Passamonti, F.; Rumi, E.; Ruggeri, M.; Rodeghiero, F.; Randi, M.L.; Bertozzi, I.; et al. Development and validation of an International Prognostic Score of thrombosis in World Health Organization–essential thrombocythemia (IPSET-thrombosis). Blood 2012, 120, 5128–5133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes, F.; Dupriez, B.; Pereira, A.; Passamonti, F.; Reilly, J.T.; Morra, E.; Vannucchi, A.M.; Mesa, R.A.; Demory, J.-L.; Barosi, G.; et al. New prognostic scoring system for primary myelofibrosis based on a study of the International Working Group for Myelofibrosis Research and Treatment. Blood 2009, 113, 2895–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passamonti, F.; Cervantes, F.; Vannucchi, A.M.; Morra, E.; Rumi, E.; Pereira, A.; Guglielmelli, P.; Pungolino, E.; Caramella, M.; Maffioli, M.; et al. A dynamic prognostic model to predict survival in primary myelofibrosis: A study by the IWG-MRT (International Working Group for Myeloproliferative Neoplasms Research and Treatment). Blood 2010, 115, 1703–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangat, N.; Caramazza, D.; Vaidya, R.; George, G.; Begna, K.; Schwager, S.; Van Dyke, D.; Hanson, C.; Wu, W.; Pardanani, A.; et al. DIPSS Plus: A Refined Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System for Primary Myelofibrosis That Incorporates Prognostic Information From Karyotype, Platelet Count, and Transfusion Status. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guglielmelli, P.; Carobbio, A.; Rumi, E.; De Stefano, V.; Mannelli, L.; Mannelli, F.; Rotunno, G.; Coltro, G.; Betti, S.; Cavalloni, C.; et al. Validation of the IPSET score for thrombosis in patients with prefibrotic myelofibrosis. Blood Cancer J. 2020, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guglielmelli, P.; Lasho, T.L.; Rotunno, G.; Mudireddy, M.; Mannarelli, C.; Nicolosi, M.; Pacilli, A.; Pardanani, A.; Rumi, E.; Rosti, V.; et al. MIPSS70: Mutation-Enhanced International Prognostic Score System for Transplantation-Age Patients With Primary Myelofibrosis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tefferi, A.; Guglielmelli, P.; Lasho, T.L.; Gangat, N.; Ketterling, R.P.; Pardanani, A.; Vannucchi, A.M. MIPSS70+ Version 2.0: Mutation and Karyotype-Enhanced International Prognostic Scoring System for Primary Myelofibrosis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 1769–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tefferi, A.; Vannucchi, A.M. Risk models in myelofibrosis—the past, present, and future. Am. J. Hematol. 2024, 99, 519–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, T.S.; Christensen, J.H.; Hasselbalch, H.C.; Pallisgaard, N. The JAK2 V617F mutation involves B- and T-lymphocyte lineages in a subgroup of patients with Philadelphia-chromosome negative chronic myeloproliferative disorders. Br. J. Haematol. 2007, 136, 745–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klampfl, T.; Gisslinger, H.; Harutyunyan, A.S.; Nivarthi, H.; Rumi, E.; Milosevic, J.D.; Them, N.C.C.; Berg, T.; Gisslinger, B.; Pietra, D.; et al. Somatic Mutations of Calreticulin in Myeloproliferative Neoplasms. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 2379–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa, R.; Yacoub, A.; Tashi, T.; Chai-Ho, W.; Yoon, C.H.; Mascarenhas, J. Navigating the peginterferon Alfa-2a shortage: Practical guidance on transitioning patients to ropeginterferon alfa-2b. Ann. Hematol. 2025, 104, 2571–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeryczynski, G.; Thiele, J.; Gisslinger, B.; Wölfler, A.; Schalling, M.; Gleiß, A.; Burgstaller, S.; Buxhofer-Ausch, V.; Sliwa, T.; Schlögl, E.; et al. Pre-fibrotic/early primary myelofibrosis vs. WHO-defined essential thrombocythemia: The impact of minor clinical diagnostic criteria on the outcome of the disease. Am. J. Hematol. 2017, 92, 885–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumi, E.; Pietra, D.; Pascutto, C.; Guglielmelli, P.; Martínez-Trillos, A.; Casetti, I.; Colomer, D.; Pieri, L.; Pratcorona, M.; Rotunno, G.; et al. Clinical effect of driver mutations of JAK2, CALR, or MPL in primary myelofibrosis. Blood 2014, 124, 1062–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guglielmelli, P.; Maccari, C.; Sordi, B.; Balliu, M.; Atanasio, A.; Mannarelli, C.; Capecchi, G.; Sestini, I.; Coltro, G.; Loscocco, G.G.; et al. Phenotypic correlations of CALR mutation variant allele frequency in patients with myelofibrosis. Blood Cancer J. 2023, 13, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J. Prognostication in myeloproliferative neoplasms, including mutational abnormalities. Blood Res. 2023, 58, S37–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gisslinger, H.; Gisslinger, B.; Schalling, M.M.; Krejcy, K.; Widmann, R.S.; Kralovics, R.; Krauth, M.-T. Effect of Ropeginterferon Alfa-2b in Prefibrotic Primary Myelofibrosis. Blood 2018, 132, 3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, T.A.; Hansen, D.L.; Ocias, L.F.; Bjerrum, O.; Brabrand, M.; Christensen, S.F.; Eickhardt-Dalbøge, C.S.; Ellervik, C.; El Fassi, D.; Frederiksen, M.; et al. Final Analysis of the Daliah Trial: A Randomized Phase III Trial of Interferon-α Versus Hydroxyurea in Patients with MPN. Blood 2023, 142, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosca, M.; Hermange, G.; Tisserand, A.; Noble, R.; Marzac, C.; Marty, C.; Catelain, C.; Rameau, P.; Gella, C.; Lenglet, J.; et al. Inferring the dynamics of mutated hemato-poietic stem and progenitor cells induced by IFNα in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood 2021, 138, 2231–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjær, L.; Cordua, S.; Holmström, M.O.; Thomassen, M.; A Kruse, T.; Pallisgaard, N.; Larsen, T.S.; de Stricker, K.; Skov, V.; Hasselbalch, H.C. Differential Dynamics of CALR Mutant Allele Burden in Myeloproliferative Neoplasms during Interferon Alfa Treatment. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czech, J.; Cordua, S.; Weinbergerova, B.; Baumeister, J.; Crepcia, A.; Han, L.; Maié, T.; Costa, I.G.; Denecke, B.; Maurer, A.; et al. JAK2V617F but not CALR mutations confer increased molecular responses to interferon-α via JAK1/STAT1 activation. Leukemia 2018, 33, 995–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumi, E.; Trotti, C.; Vanni, D.; Casetti, I.C.; Pietra, D.; Sant’antonio, E. The Genetic Basis of Primary Myelofibrosis and Its Clinical Relevance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Bitar, S.; Arcasoy, M.O. Recombinant Interferon Alfa in BCR/ ABL-Negative Chronic Myeloproliferative Neoplasms. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2024, 22, 80–89. [Google Scholar]

- Gowin, K.; Jain, T.; Kosiorek, H.; Tibes, R.; Camoriano, J.; Palmer, J.; Mesa, R. Pegylated interferon alpha – 2a is clinically effective and tolerable in myeloproliferative neoplasm patients treated off clinical trial. Leuk. Res. 2017, 54, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumi, E.; Boveri, E.; Bellini, M.; Pietra, D.; Ferretti, V.V.; Sant’aNtonio, E.; Cavalloni, C.; Casetti, I.C.; Roncoroni, E.; Ciboddo, M.; et al. Clinical course and outcome of essential thrombocythemia and prefibrotic myelofibrosis according to the revised WHO 2016 diagnostic criteria. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 101735–101744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finazzi, M.C.; Carobbio, A.; Cervantes, F.; Isola, I.M.; Vannucchi, A.M.; Guglielmelli, P.; Rambaldi, A.; Finazzi, G.; Barosi, G.; Barbui, T. CALR mutation, MPL mutation and triple negativity identify patients with the lowest vascular risk in primary myelofibrosis. Leukemia 2014, 29, 1209–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carobbio, A.; Guglielmelli, P.; Rumi, E.; Cavalloni, C.; De Stefano, V.; Betti, S.; Rambaldi, A.; Finazzi, M.C.; Thiele, J.; Vannucchi, A.M.; et al. A multistate model of survival prediction and event monitoring in prefibrotic myelofibrosis. Blood Cancer J. 2020, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carobbio, A.; Vannucchi, A.M.; Rumi, E.; De Stefano, V.; Rambaldi, A.; Carli, G.; Randi, M.L.; Gisslinger, H.; Passamonti, F.; Thiele, J.; et al. Survival expectation after thrombosis and overt-myelofibrosis in essential thrombocythemia and prefibrotic myelofibrosis: A multistate model approach. Blood Cancer J. 2023, 13, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carobbio, A.; Finazzi, G.; Thiele, J.; Kvasnicka, H.; Passamonti, F.; Rumi, E.; Ruggeri, M.; Rodeghiero, F.; Randi, M.L.; Bertozzi, I.; et al. Blood tests may predict early primary myelofibrosis in patients presenting with essential thrombocythemia. Am. J. Hematol. 2011, 87, 203–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tefferi, A.; Guglielmelli, P.; Larson, D.R.; Finke, C.; Wassie, E.A.; Pieri, L.; Gangat, N.; Fjerza, R.; Belachew, A.A.; Lasho, T.L.; et al. Long-term survival and blast transformation in molecularly annotated essential thrombocythemia, polycythemia vera, and myelofibrosis. Blood 2014, 124, 2507–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisslinger, H.; Klade, C.; Georgiev, P.; Krochmalczyk, D.; Gercheva-Kyuchukova, L.; Egyed, M.; Dulicek, P.; Illes, A.; Pylypenko, H.; Sivcheva, L.; et al. Event-free survival in patients with polycythemia vera treated with ropeginterferon alfa-2b versus best available treatment. Leukemia 2023, 37, 2129–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiladjian, J.; Klade, C.; Georgiev, P.; Krochmalczyk, D.; Gercheva-Kyuchukova, L.; Egyed, M.; Dulicek, P.; Illes, A.; Pylypenko, H.; Sivcheva, L.; et al. Event-free survival in early polycythemia vera patients correlates with molecular response to ropeginterferon alfa-2b or hydroxyurea/best available therapy (PROUD-PV/CONTINUATION-PV). HemaSphere 2025, 9, e70137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowin, K.; Thapaliya, P.; Samuelson, J.; Harrison, C.; Radia, D.; Andreasson, B.; Mascarenhas, J.; Rambaldi, A.; Barbui, T.; Rea, C.J.; et al. Experience with pegylated interferon -2a in advanced myeloproliferative neoplasms in an international cohort of 118 patients. Haematologica 2012, 97, 1570–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Zeinah, G.; Qin, A.; Gill, H.; Komatsu, N.; Mascarenhas, J.; Shih, W.J.; Zagrijtschuk, O.; Sato, T.; Shimoda, K.; Silver, R.T.; et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study to assess efficacy and safety of ropeginterferon alfa-2b in patients with early/lower-risk primary myelofibrosis. Ann. Hematol. 2024, 103, 3573–3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barosi, G.; Tefferi, A.; Gangat, N.; Szuber, N.; Rambaldi, A.; Odenike, O.; Kröger, N.; Gagelmann, N.; Talpaz, M.; Kantarjian, H.; et al. Methodological challenges in the development of endpoints for myelofibrosis clinical trials. Lancet Haematol. 2024, 11, e383–e389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, A.L.; Bjørn, M.E.; Riley, C.H.; Holmstrøm, M.; Andersen, M.H.; Svane, I.M.; Mikkelsen, S.U.; Skov, V.; Kjær, L.; Hasselbalch, H.C.; et al. B-cell frequencies and immunoregulatory phenotypes in myeloproliferative neoplasms: Influence of ruxolitinib, interferon-α2, or combination treatment. Eur. J. Haematol. 2019, 103, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIlroy, G.; Gaskell, C.; Jackson, A.; Yafai, E.; Tasker, R.; Thomas, C.; Fox, S.; Boucher, R.; Ghebretinsea, F.; Harrison, C.; et al. Fedratinib combined with ropeginterferon alfa-2b in patients with myelofibrosis (FEDORA): Study protocol for a multicentre, open-label, Bayesian phase II trial. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasselbalch, H.C.; Holmström, M.O. Perspectives on interferon-alpha in the treatment of polycythemia vera and related myeloproliferative neoplasms: Minimal residual disease and cure? Semin. Immunopathol. 2018, 41, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasselbalch, H.C.; Skov, V.; Kjær, L.; Larsen, M.K. Proof of concept of triple COMBI therapy to prohibit MPN progression to AML. Br. J. Haematol. 2023, 204, 16–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro, F.A.; Mehdipour, P.; Chakravarthy, A.; Ettayebi, I.; Yau, H.L.; Medina, T.S.; Marhon, S.A.; de Almeida, F.C.; Bianco, T.M.; Arruda, A.G.F.; et al. Ratio of stemness to interferon signalling as a biomarker and therapeutic target of myeloproliferative neoplasm progression to acute myeloid leukaemia. Br. J. Haematol. 2023, 204, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Entire Cohort (n = 55) | JAK2V617F Mutation (n = 33) | CALR Mutation (n = 22) | p-Value # |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at start of interferon treatment, median (quartiles) | 56.43 (49.51; 68.04) | 59.72 (52.93; 68.04) | 54.10 (35.97; 67.71) | 0.12 |

| Time (days) from diagnosis to study entry, median (quartiles) | 74.0 (29.0; 403.0) | 74.0 (35.0; 403.0) | 78.50 (29.0; 336.0) | 0.84 |

| JAK2/CALR allele burden at study entry, %, median (quartiles) | 12.00 (5.30; 18.95) | 24.00 (18.00; 32.00) | 0.005 | |

| PLTs, ×109/L, median (quartiles) | 672.0 (565.0; 962.0) | 676.00 (565.00; 896.00) | 668.0 (568.0; 1138.0) | 0.56 |

| WBCs, ×109/L, median (quartiles) | 9.40 (9.40; 11.10) | 9.90 (8.60; 11.80) | 8.65 (6.40; 10.40) | 0.049 |

| Erythrocytes, ×1012/L, median (quartiles) | 4.64 (4.37; 5.09) | 4.79 (4.50; 5.31) | 4.52 (4.30; 4.73) | 0.006 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 138.0 (128.0; 147.0) | 139.0 (133.0; 151.0) | 134.0 (126.0; 139.0) | 0.080 |

| LDH, U/L | 229.0 (192.0; 281.0) | 213.0 (178.0; 251.0) | 263.0 (205.0; 289.0) | 0.028 |

| PLTs ≤ 400 × 109/L at study entry, n (%) | 6 (10.91) | 3 (9.09) | 3 (13.64) | >0.99 |

| WBCs ≤ 9 × 109/L at study entry, n (%) | 24 (43.64) | 11 (33.33) | 13 (59.09) | 0.27 |

| LDH ≤ 247 U/L at study entry, n (%) | 34 (61.82) | 24 (72.73) | 10 (45.45) | >0.99 |

| Left shift at study entry, n (%) | 10 (18.18) | 5 (15.15) | 5 (22.73) | 0.50 |

| Splenomegaly, n (%), n = 37 | 18 (48.65) | 7 (36.84) | 11 (61.11) | 0.19 |

| Fibrosis grade at study entry > 0, n (%) | 23 (41.82) | 12 (36.36) | 11 (50.0) | 0.41 |

| DIPSS-plus at interferon start, n (%), n = 55 | ||||

| Low | 31 (56.36) | 17 (51.52) | 14 (63.64) | 0.42 |

| Intermediate 1 | 24 (43.64) | 16 (48.48) | 8 (36.36) | |

| Intermediate 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| High | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| MIPSS70 at interferon start, n (%), n = 51 | ||||

| Low | 44 (86.27) | 23 (79.31) | 21 (95.45) | 0.12 |

| Intermediate | 7 (13.73) | 6 (20.69) | 1 (4.55) | |

| High | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| MIPSS70-plus at interferon start, n (%), n = 31 | ||||

| Very low | 5 (16.13) | 1 (5.00) | 4 (36.36) | 0.008 |

| Low | 20 (64.52) | 13 (65.00) | 7 (63.64) | |

| Intermediate | 6 (19.35) | 6 (30.00) | 0 | |

| High | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Very high | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 24 Months | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | JAK2 (n = 20) | CALR (n = 18) | p-Value # | |

| JAK2/CALR allele burden, n = 33 | %, median (quartiles) | 5.05 (2.92; 15.51) | 19.41 (13.40; 29.21) | 0.006 |

| Delta allele burden, n = 33 | %, median (95% KI) (IF Start = 100%) | −45.12 (−62.03; −12.75) | −14.61 (−18.80; −4.18) | 0.084 |

| Molecular response ≥ 25% *, n = 24 | n (%) | 8 (72.73) | 3 (23.08) | 0.038 |

| Molecular response ≥ 50% *, n = 24 | n (%) | 6 (54.55) | 1 (7.69) | 0.023 |

| PLTs, ×109/L | Median (quartiles) | 315.75 (284.31; 353.60) | 299.54 (244.48; 353.07) | 0.91 |

| Delta PLTs, ×109/L | Median (quartiles) | −404.95 (−673.46; −285.41) | −401.81 (−731.55; −247.86) | 0.58 |

| PLTs ≤ 400 × 109/L | n (%) | 18 (90.00) | 14 (77.78) | 0.40 |

| WBCs, × 109/L | Median (quartiles) | 5.25 (4.43; 6.86) | 3.87 (3.52; 4.53) | 0.004 |

| WBCs ≤ 9 × 109/L | n (%) | 19 (95.00) | 18 (100.00) | >0.99 |

| Delta WBCs, ×109/L | Median (quartiles) | −5.50 (−5.50; −2.40) | −4.21 (−6.58; −2.03) | 0.55 |

| Left shift | n (%) | 0 | 1 (5.56) | 0.47 |

| LDH, U/L | Median (quartiles) | 158.38 (128.56; 186.36) | 183.62 (152.56; 213.77) | 0.099 |

| Delta LDH, U/L | Median (quartiles) | −48.68 (−89.17; −13.54) | −55.88 (−95.06; −22.46) | 0.83 |

| LDH ≤ 247 U/L | n (%) | 20 (100.00) | 16 (88.89) | 0.22 |

| Splenomegaly, n = 28 | n (%) | 6 (40.00) | 6 (46.15) | >0.99 |

| Hematological responder | n (%) | 18 (90.00) | 13 (72.22) | 0.22 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Machherndl-Spandl, S.; Kiehberger, M.; Sygulla, V.; Kaynak, E.; Zach, O.; Webersinke, G.; Gruber-Rossipal, C.; Beham-Schmid, C.; Maier, E.; Strassl, I.; et al. Rapid Hematological and Molecular Response to Pegylated Interferon in WHO-Defined Pre-Fibrotic Myelofibrosis. Cancers 2025, 17, 3940. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243940

Machherndl-Spandl S, Kiehberger M, Sygulla V, Kaynak E, Zach O, Webersinke G, Gruber-Rossipal C, Beham-Schmid C, Maier E, Strassl I, et al. Rapid Hematological and Molecular Response to Pegylated Interferon in WHO-Defined Pre-Fibrotic Myelofibrosis. Cancers. 2025; 17(24):3940. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243940

Chicago/Turabian StyleMachherndl-Spandl, Sigrid, Marcel Kiehberger, Veronika Sygulla, Emine Kaynak, Otto Zach, Gerald Webersinke, Christine Gruber-Rossipal, Christine Beham-Schmid, Eva Maier, Irene Strassl, and et al. 2025. "Rapid Hematological and Molecular Response to Pegylated Interferon in WHO-Defined Pre-Fibrotic Myelofibrosis" Cancers 17, no. 24: 3940. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243940

APA StyleMachherndl-Spandl, S., Kiehberger, M., Sygulla, V., Kaynak, E., Zach, O., Webersinke, G., Gruber-Rossipal, C., Beham-Schmid, C., Maier, E., Strassl, I., Clausen, J., Nikoloudis, A., Schimetta, W., Rumpold, H., & Buxhofer-Ausch, V. (2025). Rapid Hematological and Molecular Response to Pegylated Interferon in WHO-Defined Pre-Fibrotic Myelofibrosis. Cancers, 17(24), 3940. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243940