The Role of Intraoperative Flow Cytometry in Surgical Oncology: A Systematic Review

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

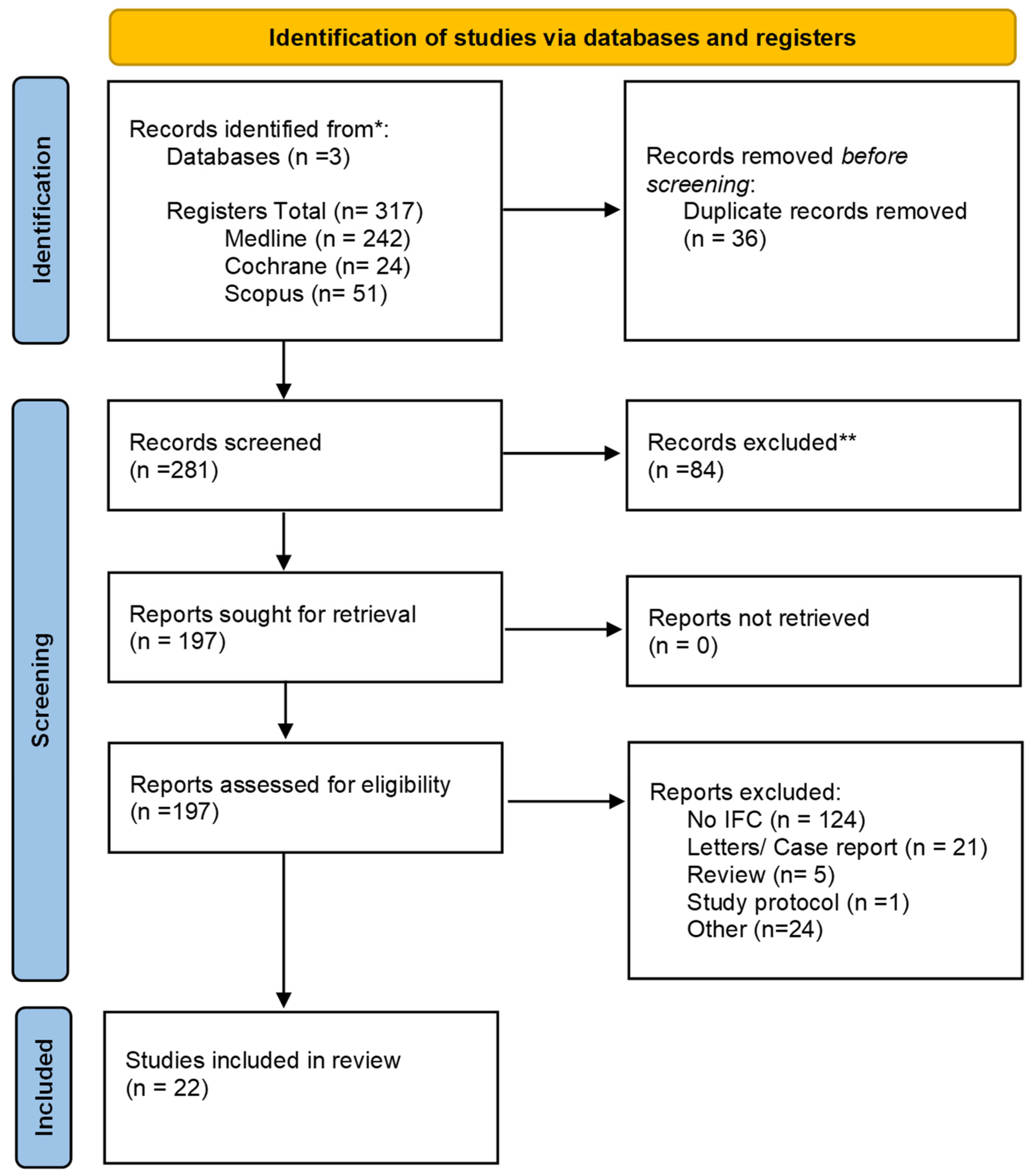

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Risk of Bias and Applicability Assessment

2.6. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Search Findings

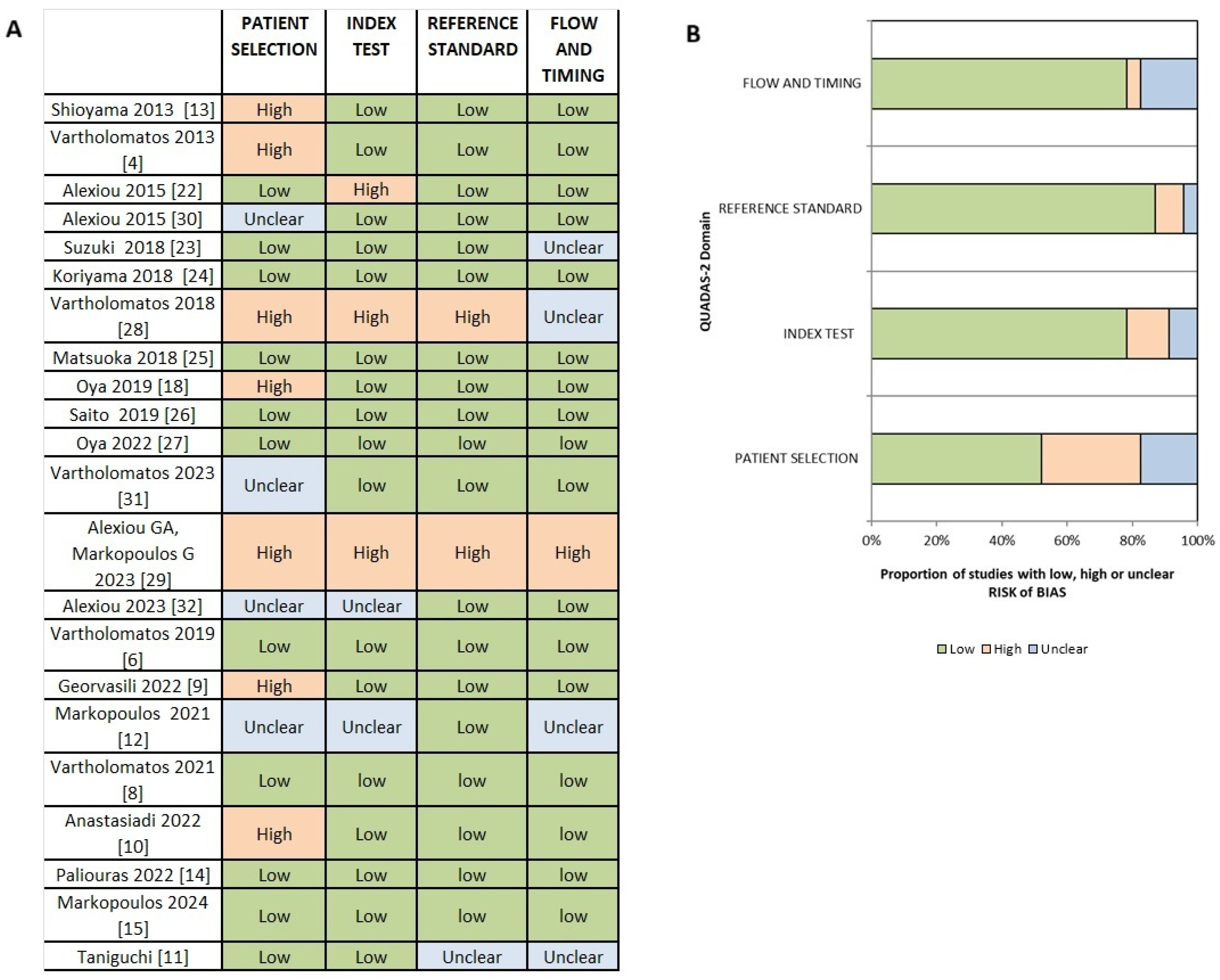

3.2. Risk of Bias and Applicability Assessment

3.3. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.4. Qualitative Synthesis

3.4.1. Intracranial Tumors

3.4.2. Head and Neck Cancer

3.4.3. Gastrointestinal and Liver Cancer

3.4.4. Breast Cancer and Gynecological Cancer

3.4.5. Bladder Cancer

3.4.6. Skin Cancer

3.5. Sensitivity Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Risk of Bias and Certainty of Evidence

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 5-ALA | 5-Aminolevulinic acid |

| AGR | Annual growth rate |

| AUC | Area under the ROC curve |

| CD | Cluster of differentiation |

| CD3-FITC | CD3 antigen labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| DA | DNA aneuploidy |

| DI | DNA index |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| FC | Flow cytometry |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| FGR | Fluorescence-guided resection |

| G0/G1 | Gap 0/Gap 1 phases of the cell cycle |

| G2/M | Gap 2/Mitosis phases of the cell cycle |

| GBM | Glioblastoma |

| GFP | Green fluorescent protein |

| GIST | Gastrointestinal stromal tumor |

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HGG | High-grade glioma |

| IDH1 | Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 |

| IFC | Intraoperative flow cytometry (preferred form used throughout) |

| iMRI | Intraoperative magnetic resonance imaging |

| Ki-67/MIB-1 | Proliferation marker (MIB-1 antibody against Ki-67) |

| LGG | Low-grade glioma |

| MI | Malignancy or mitotic index |

| n/a | not available/applicable |

| NPV | Negative predictive value |

| PBMC | Peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

| PCNSL | Primary central nervous system lymphoma |

| PI | Proliferation index |

| PPV | Positive predictive value |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| QUADAS-2 | Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies 2 |

| S-phase | DNA synthesis phase of the cell cycle |

| SPF | S-phase fraction |

| TI | Tumor index (combined S-phase + G2/M fractions) |

| imPI/cPI | Intrameatal PI to cisternal PI ratio |

References

- McKinnon, K.M. Flow Cytometry: An Overview. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. 2018, 120, 5.1.1–5.1.11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liaropoulos, I.; Liaropoulos, A.; Liaropoulos, K. Critical Assessment of Cancer Characterization and Margin Evaluation Techniques in Brain Malignancies: From Fast Biopsy to Intraoperative Flow Cytometry. Cancers 2023, 15, 4843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Global Burden of Disease 2019 Cancer Collaboration; Kocarnik, J.M.; Compton, K.; Dean, F.E.; Fu, W.; Gaw, B.L.; Harvey, J.D.; Henrikson, H.J.; Lu, D.; Pennini, A.; et al. Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of Life Lost, Years Lived with Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life Years for 29 Cancer Groups From 2010 to 2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. JAMA Oncol. 2022, 8, 420–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartholomatos, G.; Alexiou, G.A.; Batistatou, A.; Kyritsis, A.P.; Voulgaris, S. Intraoperative diagnosis. J. Neurosurg. 2013, 119, 528–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shioyama, T.; Muragaki, Y.; Maruyama, T.; Komori, T.; Iseki, H. Intraoperative flow cytometry analysis of glioma tissue for rapid determination of tumor presence and its histopathological grade: Clinical article. J. Neurosurg. 2013, 118, 1232–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartholomatos, G.; Basiari, L.; Exarchakos, G.; Kastanioudakis, I.; Komnos, I.; Michali, M.; Markopoulos, G.S.; Batistatou, A.; Papoudou-Bai, A.; Alexiou, G.A. Intraoperative flow cytometry for head and neck lesions. Assessment of malignancy and tumour-free resection margins. Oral Oncol. 2019, 99, 104344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastanioudakis, I.; Basiari, L. Intraoperative Flow Cytometry in Head and Neck Malignancies; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartholomatos, G.; Harissis, H.; Andreou, M.; Tatsi, V.; Pappa, L.; Kamina, S.; Batistatou, A.; Markopoulos, G.S.; Alexiou, G.A. Rapid Assessment of Resection Margins During Breast Conserving Surgery Using Intraoperative Flow Cytometry. Clin. Breast Cancer 2021, 21, e602–e610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiadi, Z.; Mantziou, S.; Akrivis, C.; Paschopoulos, M.; Balasi, E.; Lianos, G.D.; Alexiou, G.A.; Mitsis, M.; Vartholomatos, G.; Markopoulos, G.S. Intraoperative Flow Cytometry for the Characterization of Gynecological Malignancies. Biology 2022, 11, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georvasili, V.K.; Markopoulos, G.S.; Batistatou, A.; Mitsis, M.; Messinis, T.; Lianos, G.D.; Alexiou, G.; Vartholomatos, G.; Bali, C.D. Detection of cancer cells and tumor margins during colorectal cancer surgery by intraoperative flow cytometry. Int. J. Surg. 2022, 104, 106717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, K.; Suzuki, A.; Serizawa, A.; Kotake, S.; Ito, S.; Suzuki, K.; Yamada, T.; Noguchi, T.; Amano, K.; Ota, M.; et al. Rapid Flow Cytometry of Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumours Closely Matches the Modified Fletcher Classification. Anticancer Res. 2021, 41, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markopoulos, G.S.; Glantzounis, G.K.; Goussia, A.C.; Lianos, G.D.; Karampa, A.; Alexiou, G.A.; Vartholomatos, G. Touch Imprint Intraoperative Flow Cytometry as a Complementary Tool for Detailed Assessment of Resection Margins and Tumor Biology in Liver Surgery for Primary and Metastatic Liver Neoplasms. Methods Protoc. 2021, 4, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman, E. Utilizing Intraoperative Flow Cytometry to Accurately Characterize Bladder Cancer Cells. Surg. Curr. Res. 2022, 12, 001–002. [Google Scholar]

- Paliouras, A.; Markopoulos, G.S.; Tsampalas, S.; Mantziou, S.; Giannakis, I.; Baltogiannis, D.; Glantzounis, G.K.; Alexiou, G.A.; Lampri, E.; Sofikitis, N.; et al. Accurate Characterization of Bladder Cancer Cells with Intraoperative Flow Cytometry. Cancers 2022, 14, 5440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markopoulos, G.; Lampri, E.; Tragani, I.; Kourkoumelis, N.; Vartholomatos, G.; Seretis, K. Intraoperative Flow Cytometry for the Rapid Diagnosis and Validation of Surgical Clearance of Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer: A Prospective Clinical Feasibility Study. Cancers 2024, 16, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexiou, G.A.; Vartholomatos, G.; Kobayashi, T.; Voulgaris, S.; Kyritsis, A.P. The emerging role of intraoperative flow cytometry in intracranial tumor surgery. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2020, 192, 105742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirós-Caso, C.; Arias Fernández, T.; Fonseca-Mourelle, A.; Torres, H.; Fernández, L.; Moreno-Rodríguez, M.; Ariza-Prota, M.Á.; López-González, F.J.; Carvajal-Álvarez, M.; Alonso-Álvarez, S.; et al. Routine flow cytometry approach for the evaluation of solid tumor neoplasms and immune cells in minimally invasive samples. Cytometry B Clin. Cytom. 2022, 102, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oya, S.; Yoshida, S.; Tsuchiya, T.; Fujisawa, N.; Mukasa, A.; Nakatomi, H.; Saito, N.; Matsui, T. Intraoperative quantification of meningioma cell proliferation potential using rapid flow cytometry reveals intratumoral heterogeneity. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 2793–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitsma, J.B.; Rutjes, A.W.; Whiting, P.; Yang, B.; Leeflang, M.M.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Deeks, J.J. Assessing Risk of Bias and Applicability. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Diagnostic Test Accuracy, 1st ed.; Deeks, J.J., Bossuyt, P.M., Leeflang, M.M., Takwoingi, Y., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 169–201. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9781119756194.ch8 (accessed on 19 March 2024).

- Whiting, P.F.; Rutjes, A.W.S.; Westwood, M.E.; Mallett, S.; Deeks, J.J.; Reitsma, J.B.; QUADAS-2 Group. QUADAS-2: A revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexiou, G.A.; Vartholomatos, G.; Stefanaki, K.; Lykoudis, E.G.; Patereli, A.; Tseka, G.; Tzoufi, M.; Sfakianos, G.; Prodromou, N. The Role of Fast Cell Cycle Analysis in Pediatric Brain Tumors. Pediatr. Neurosurg. 2015, 50, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, A.; Maruyama, T.; Nitta, M.; Komori, T.; Ikuta, S.; Chernov, M.; Tamura, M.; Kawamata, T.; Muragaki, Y. Evaluation of DNA ploidy with intraoperative flow cytometry may predict long-term survival of patients with supratentorial low-grade gliomas: Analysis of 102 cases. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2018, 168, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koriyama, S.; Nitta, M.; Shioyama, T.; Komori, T.; Maruyama, T.; Kawamata, T.; Muragaki, Y. Intraoperative Flow Cytometry Enables the Differentiation of Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma from Glioblastoma. World Neurosurg. 2018, 112, e261–e268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, G.; Eguchi, S.; Anami, H.; Ishikawa, T.; Yamaguchi, K.; Nitta, M.; Muragaki, Y.; Kawamata, T. Ultrarapid Evaluation of Meningioma Malignancy by Intraoperative Flow Cytometry. World Neurosurg. 2018, 120, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, T.; Muragaki, Y.; Shioyama, T.; Komori, T.; Maruyama, T.; Nitta, M.; Yasuda, T.; Hosono, J.; Okamoto, S.; Kawamata, T. Malignancy Index Using Intraoperative Flow Cytometry is a Valuable Prognostic Factor for Glioblastoma Treated With Radiotherapy and Concomitant Temozolomide. Neurosurgery 2019, 84, 662–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oya, S.; Yoshida, S.; Hanakita, S.; Inoue, M. Quantitative Evaluation of Proliferative Potential Using Flow Cytometry Reveals Intratumoral Heterogeneity and Its Relevance to Tumor Characteristics in Vestibular Schwannomas. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 1594–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartholomatos, G.; Alexiou, G.A.; Voulgaris, S.; Kyritsis, A.P. Intraoperative Immunophenotypic Analysis for Diagnosis and Classification of Primary Central Nervous System Lymphomas. World Neurosurg. 2018, 117, 464–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexiou, G.A.; Markopoulos, G.; Voulgaris, S.; Vartholomatos, G. Usefulness of intraoperative rapid flow cytometry in the surgical treatment of brain tumors. Neuropathology 2023, 43, 273–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexiou, G.A.; Vartholomatos, G.; Goussia, A.; Batistatou, A.; Tsamis, K.; Voulgaris, S.; Kyritsis, A.P. Fast cell cycle analysis for intraoperative characterization of brain tumor margins and malignancy. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2015, 22, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartholomatos, G.; Markopoulos, G.S.; Vartholomatos, E.; Goussia, A.C.; Dova, L.; Dimitriadis, S.; Mantziou, S.; Zoi, V.; Nasios, A.; Sioka, C.; et al. Assessment of Gliomas’ Grade of Malignancy and Extent of Resection Using Intraoperative Flow Cytometry. Cancers 2023, 15, 2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexiou, G.A.; Markopoulos, G.S.; Vartholomatos, E.; Goussia, A.C.; Dova, L.; Dimitriadis, S.; Mantziou, S.; Zoi, V.; Nasios, A.; Sioka, C.; et al. Intraoperative Flow Cytometry for the Evaluation of Meningioma Grade. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 832–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, H. Intra-operative frozen section consultation: Concepts, applications and limitations. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2006, 13, 4–12. [Google Scholar]

- Amit, S.; Khan, L.; Chakraborty, S.; Pai, M.R.; Naik, R. Diagnostic Utility, Errors and Limitations of Frozen Section in Surgical Pathology. Int. J. Acad. Med. Pharm. 2024, 6, 742–747. [Google Scholar]

- Hadjipanayis, C.G.; Stummer, W. 5-ALA and FDA approval for glioma surgery. J. Neurooncol. 2019, 141, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rybaczek, M.; Chaurasia, B. Advantage and challenges in the use of 5-Aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) in neurosurgery. Neurosurg. Rev. 2024, 47, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madani, D.; Fonseka, R.D.; Kim, S.J.; Tang, P.; Muralidharan, K.; Chang, N.; Wong, J. Comparing the Rates of Further Resection After Intraoperative MRI Visualisation of Residual Tumour Between Brain Tumour Subtypes: A 17-Year Single-Centre Experience. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Roder, C.; Haas, P.; Tatagiba, M.; Ernemann, U.; Bender, B. Technical limitations and pitfalls of diffusion-weighted imaging in intraoperative high-field MRI. Neurosurg. Rev. 2021, 44, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.R. Rituximab (monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody): Mechanisms of action and resistance. Oncogene 2003, 22, 7359–7368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koriyama, S.; Matsui, Y.; Shioyama, T.; Onodera, M.; Tamura, M.; Kobayashi, T.; Ro, B.; Masui, K.; Komori, T.; Muragaki, Y.; et al. High-precision intraoperative diagnosis of gliomas: Integrating imaging and intraoperative flow cytometry with machine learning. Front. Neurol. 2025, 16, 1647009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref. | Study | Year | Type of Study | Object | No of Patients | IFC Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [5] | Shioyama et al. | 2013 | Prospective | Brain Tumors | 81 | Malignant Index (MI) |

| [4] | Vartholomatos et al. | 2013 | n/a | Brain Tumors | 63 | Cell Cycle Fractions |

| [22] | Alexiou et al. | 2015 | Retrospective | Pediatric Brain Tumors | 68 | Cell Cycle fractions |

| [30] | Alexiou et al. | 2015 | Prospective | Brain Tumors | 31 | Cell Cycle Fractions |

| [23] | Suzuki et al. | 2018 | Retrospective | Brain Tumors | 102 | Aneuploidy |

| [24] | Koriyama et al. | 2018 | Retrospective | Brain Tumors | 250 | MI |

| [25] | Matsuoka et al. | 2018 | Prospective | Brain Tumors | 117 | MI |

| [28] | Vartholomatos et al. | 2018 | n/a | Brain Tumors | 5 | CD Markers |

| [18] | Oya et al. | 2019 | Prospective | Brain Tumors | 50 | Proliferation Index (PI) |

| [26] | Saito et al. | 2019 | Retrospective | Brain Tumors | 102 | MI |

| [27] | Oya et al. | 2022 | Prospective | Brain Tumors | 34 | PI |

| [31] | Vartholomatos et al. | 2023 | Retrospective | Brain Tumors | 81 | Tumor Index (ΤΙ) |

| [32] | Alexiou et al. | 2023 | Retrospective | Brain Tumors | 59 | ΤΙ |

| [29] | Alexiou, Markopoulos et al. | 2023 | n/a | Brain Tumors | n/a | CD Markers |

| [6] | Vartholomatos et al. | 2019 | Prospective | Head and Neck Cancer | 70 | Cell Cycle Fractions TI |

| [10] | Georvasili et al. | 2022 | Prospective | Colorectal Cancer | 106 | ΤΙ Cell Cycle Fraction |

| [12] | Markopoulos et al. | 2021 | n/a | Primary and Metastatic Liver Neoplasms | 9 | TI DNA Index (DI) |

| [11] | Taniguchi et al. | 2021 | Retrospective | Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors (GIST) | 18 | DNA Aneuploidy (DA) DI S-phase fraction (SPF) |

| [8] | Vartholomatos et al. | 2021 | Prospective | Breast Cancer | 99 | MI Cell Cycle Fractions |

| [9] | Anastasiadi et al. | 2022 | Retrospective | Gynecological Cancer | 42 (50 but 8 samples have been excluded) | Cell Cycle Fractions TI |

| [14] | Paliouras et al. | 2022 | Prospective | Bladder Cancer Normal | 52 | Cell Cycle Fractions TI |

| [15] | Markopoulos et al. | 2024 | Prospective | Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer | 30 | Cell Cycle Fractions TI |

| Study | Year | Object | No of Patients | IFC Parameter | Sensitivity | Specificity | Cut-Off | Outcome | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shioyama et al. [5] | 2013 | Glioma grade | 81 | Malignant Index (MI) | n/a | n/a | MI: 6.9% | Lower MI in LGG | - |

| Vartholomatos et al. [4] | 2013 | LGG vs. HGG | 63 | Cell Cycle Fractions | 82.2% 94.1% | 100% 100% | G0/G1: 78% S phase: 4.3% | High accuracy | Letter to Editor |

| Meningiomas | n/a | n/a | n/a | Grade indication based on cell cycle | |||||

| Brain metastasis | n/a | n/a | Low G0/G1, High S phase and high G2/M | Primary vs. metastasis | |||||

| Alexiou et al. [22] | 2015 | Grade I/II vs. III/IV | 68 | Cell Cycle Fractions | 80% | 88.9% | G0/G1: 81% | Grading | Pediatric population |

| Alexiou et al. [30] | 2015 | LGG vs. HGG | 31 | Cell Cycle Fractions | 92.3% 84.6% 92.3% | 91.7% 91.7% 91.7% | G0/G1: 75% S: 6% Mitosis: 9.7% | Grading | Optimal cut-off G0/G1 75% |

| Koriyama et al. [24] | 2018 | GBM vs. PCNSL | 250 | MI | 89.3%/ | 93.7% | S1: 6.24% and S2: 1.42% | Strong separation of PCNSL vs. GBM | |

| Matsuoka et al. [25] | 2018 | Meningiomas Grade | 117 | MI | 64.7% | 85% | MI: 8% | Grading | Asian patients |

| Vartholomatos et al. [28] | 2018 | PCNSL vs. GBM | 5 | CD | n/a | n/a | CD45/CD29/CD 20 in PCNSL | Immunotyping | Letter to Editor |

| Vartholomatos et al. [31] | 2023 | LGG vs. HGG Glioma Margins | 81 | Tumor Index | 61.4% | 100% | 17% | All aneuploid tumors = HGG | Useful for assessing tumor grade and extent of infiltration |

| Alexiou et al. [32] | 2023 | Meningiomas Low vs. High Grade | 59 | Tumor Index | 90.2% | 72.2% | TI: 11.4% | High-grade → higher S phase and Mitosis and lower G0/G1 phase fraction | Good correlation |

| Alexiou, Markopoulos et al. [29] | 2023 | PCNSL | n/a | CD markers | n/a | n/a | CD 3/CD 45/CD 20 detection | PCNSL diagnosis | Letter to Editor |

| Vartholomatos et al. [6] | 2019 | Head and Neck Cancer Benign vs. neoplastic | 70 | Cell cycle fractions | 97.4% 97.4% 80% 97.4% | 90% 73.3% 86.7% 90% | G0/G1: 88% S phase: 6% G2/M: 5% TI > 10% | Characterization of head and neck lesions | All aneuploid lesions were neoplastic |

| Markopoulos et al. [12] | 2021 | Primary and Metastatic Liver Neoplasms | 9 | Tumor Index (TI) DNA Index | n/a | n/a | HCC → DNA index of 1 and tumor index of 10–35% In metastatic disease → DNA index ≥1.5, indicative aneuploidy | Cell characterization and margin detection during the excision Primary vs. Metastatic lesion | Study protocol—preliminary study |

| Study | Year | Object | No of Patients | IFC Parameter | Sensitivity | Specificity | Cut-Off | Outcome | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shioyama et al. [5] | 2013 | Gliomas margins | 81 | Malignant Index (MI) | 88% | 88% | MI: 6.9% | Good discrimination between tumor and normal tissue | MI higher in neoplastic tissue |

| Alexiou et al. [22] | 2015 | Neoplastic vs. normal | 68 | Cell Cycle fractions | 100% 100% 98.4% | 100% 100% 100% | G0/G1: 98% Mitosis ≤ 2% S phase: 2.2% | Excellent accuracy | Pediatric population |

| Alexiou et al. [30] | 2015 | GBM margins | 31 | Cell Cycle Fractions | n/a | n/a | Lower G0/G1 and higher S phase fractions | Margins | - |

| Georvasili et al. [10] | 2022 | Colorectal cancer Normal vs. cancer tissue | 106 | Tumor Index (TI) | 82.2% | 99.96% | TI cut-off 10.5% | Accuracy of TI > 90% | TI is linked with the tumor stage (lower in advanced stages) |

| Rectal cancer margins | Cell Cycle Fraction | n/a | n/a | G0/G1 for normal, cancer without neoadjuvant therapy and cancer samples with neoadjuvant therapy were 93.51%, 73.75%, and 87.08% | Accuracy of IFC was 79%, 88% and 85%, respectively; G0/G1 showed significant difference between normal and cancer samples | Neoadjuvant therapy reduced cancer cell replication | |||

| Vartholomatos et al. [8] | 2021 | Breast cancer margins | 99 | Malignancy Index (MI) Cell Cycle Fractions | 93.3% | 92.4 | In diploid MI cutoff >5% Mean tumor fractions: G0/G1 77.3%, S 7.3%, G2/M 15.3%, MI 22.6%. Diploid tumors: ↓ G0/G1, ↑ G2/M, ↑ MI | Accuracy of IFC: 92.5% IFC identified 54/506 positive margins vs. 14 by pathology and 48 cytology Aneuploid detection limit: 0.4–0.8% | IFC offer a rapid evaluation of the margins in breast cancer surgery |

| Anastasiadi et al. [9] | 2022 | Gynecological cancer Normal vs. cancer tissue | 42 (50 but 8 samples have been excluded) | Cell Cycle Fractions TI | 100% | 90.5% | G0/G1 < 94.5% or TI > 6.5% | 100% accuracy | - |

| Paliouras et al. [14] | 2022 | Bladder cancer Normal vs. cancer tissue | 52 | Cell Cycle Fractions TI | 100% | 96.2% | G0/G1 < 93.5% or TI > 6.5% | 98.2% accuracy PPV 96.2% NPV 100% | DNA index and proliferation analysis support tumor margin assessment |

| Markopoulos et al. [15] | 2024 | Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer | 30 | Cell Cycle Fractions TI | 95.2% | 87.1% | G0/G1 < 94.25% or TI > 5.75% | 91.1% accuracy | Higher G0/G1 fraction and lower TI in tumor margins |

| Study | Year | Object | No of Patients | IFC Parameter | Sensitivity | Specificity | Cut-Off | Outcome | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vartholomatos et al. [4] | 2013 | GBM prognosis | n/a (number of GBM patients not specified) | Cell Cycle Fractions | n/a | n/a | Lower survival with G0/G1 ≤ 69% S phase > 6% | Predicts poor survival | Letter to Editor |

| Suzuki et al. [23] | 2018 | LGG | 102 | Aneuploidy | n/a | n/a | Aneuploidy tumors have more aggressive behavior | Aneuploidy = poor prognosis | DNA ploidy as prognostic factor in LGG and especially in DA |

| Oya et al. [18] | 2019 | Meningiomas | 50 | PI | n/a | n/a | PI correlated with MIB-1. Higher PI → higher AGR and more pial feeders | Proliferation Heterogeneity | PI location varied with AGR. High ACR → peaked in center or periphery. Low ACR → PI peaked in dural attachment |

| Saito et al. [19] | 2019 | GBM prognosis | 102 | MI | 70% | 70% | 2 years survival cut-off vs. no 2 years survival MI 26.3% | Better survival with MI ≥ 26.3% | Linked to IDH1 status. MI greater impact on patient with IDH1 wild type |

| Oya et al. [27] | 2022 | Vestibular Schwannoma | 34 | Proliferation Index (PI) | n/a | n/a | imPI/cPI ratio | Heterogeneity Analysis High imPI/cPI linked to larger size, recurrence | Procedure ~10 min, MIB-1 correlated (R = 0.57) Not significant |

| Taniguchi [11] | 2021 | GIST metastatic risk | 18 | DNA aneuploidy (DA) DNA index (DI) S-phase fraction (SPF) | Low risk → 100% Intermediate risk GIST→ 71.4%, High-risk GIST → 100% | Low risk → 87.5% Intermediate risk GIST→ 100%, High-risk GIST → 94.1% | Calculate the metastatic risk of GIST with DA, DI SPF | Low risk size ≤ 5 cm, absence of DA and DI < 1.5 and SPF < 2 Intermediate risk size ≤ 5 cm, presence of DA or DI ≥ 1.5 or SPF ≥ 2 or size between 5.1 and 10 cm, absence of DA and DI < 1.5 and SPF < 2 | Accuracy from 88.9 to 94.4% IFC and Tumor Size → Correlation with the modified Fletcher risk classification. |

| Tumor Type | Study/Year | IFC Parameter(s) | Cut-Off/Threshold Value(s) | Interpretation/Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low- vs. High-Grade Gliomas (LGG/HGG) | Shioyama 2013 [5] | Malignancy Index (MI) | MI 6.9% | Higher MI distinguishes tumor from normal tissue |

| Vartholomatos 2013 [4] | Cell cycle fractions | G0/G1 78% S phase 4.3% | Distinguishes LGG vs. HGG | |

| Alexiou 2015 [30] | Cell cycle fractions | G0/G1 75% S phase 6% MITOSIS 9.7% | Grading accuracy > 90% | |

| Vartholomatos 2023 [31] | Tumor Index (TI) | TI 17% | All aneuploid tumors = HGG; useful for grade and infiltration | |

| Glioblastoma (GBM) | Saito 2019 [26] | MI | 26.3% | MI ≥ 26.3% associated with better 2-year survival (IDH1-dependent) |

| Koriyama 2018 [24] | S1, S2 cell cycle fractions | S1 6.24% S2 1.42% | Distinguishes GBM vs. PCNSL | |

| Vartholomatos 2013 [4] | Cell cycle fractions Lower survival | G0/G1 ≤ 69% S phase > 6% | Predicts poor survival lower survival | |

| Meningiomas | Matsuoka 2018 [25] | MI | MI 8% | Differentiates low- vs. high-grade tumors |

| Alexiou 2023 [32] | TI | TI 11.4% | High-grade → higher S and M phases, lower G0/G1 | |

| Primary CNS Lymphoma (PCNSL) | Vartholomatos 2018 [28] Alexiou 2023 [32] | CD markers | — | Diagnostic immunophenotyping (CD45, CD20, CD29) |

| Vestibular Schwannoma | Oya 2022 [27] | imPI/cPI ratio | — | High ratio → larger size, recurrence risk |

| Head and Neck Tumors | Vartholomatos 2019 [6] | Cell cycle fractions TI | G0/G1 88% S phase 6% G2/M 5% TI > 10% | Distinguishes benign vs. malignant lesions |

| Colorectal Cancer | Georvasili 2022 [10] | TI Cell cycle fractions | TI 10.5%; G0/G1 ≈ 74–93% | Differentiates normal, cancer, and neoadjuvant-treated tissue |

| Liver Tumors (HCC/Metastases) | Markopoulos 2021 [12] | TI DNA Index (DI) | HCC TI 10–35%; DI = 1 (normal)/≥ 1.5 (metastatic) | Differentiates primary vs. metastatic lesions |

| Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor (GIST) | Taniguchi 2021 [11] | DA, DI, SPF | DI < 1.5 and SPF < 2 → low risk DI ≥ 1.5 or SPF ≥ 2 → higher risk | Correlates with modified Fletcher risk classification |

| Breast Cancer | Vartholomatos 2021 [8] | MI Cell cycle fractions | MI > 5% G0/G1 77% S phase 7% G2/M 15% | Rapid margin assessment; detects aneuploidy ≥ 0.4% |

| Gynecologic Tumors | Anastasiadi 2022 [9] | G0/G1 TI | G0/G1 < 94.5% or TI > 6.5% | Differentiates normal vs. malignant tissue |

| Bladder Cancer | Paliouras 2022 [14] | G0/G1 TI | G0/G1 < 93.5% or TI > 6.5% | 98% accuracy for tumor margin assessment |

| Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer | Markopoulos 2024 [15] | G0/G1 TI | G0/G1 < 94.25% or TI > 5.75% | 91% accuracy higher G0/G1 fraction in tumor margins |

| Technique | Diagnostic Principle | Average Time to Result | Main Advantages | Limitations | Approximate Cost/Accessibility | Applicable Tumor Types |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intraoperative Flow Cytometry (IFC) | Quantitative cell analysis using DNA content, ploidy, and cell cycle distribution | 5–10 min | Rapid analysis Quantitative results Small sample required Detects ploidy and proliferative Indices Reproducible and easily integrated into workflow | Requires flow cytometer and trained operator Limited reference standards for non-brain tumors No available protocols and standards cut-off values | Low (uses existing cytometry equipment in most centers) | Brain, head and neck, colorectal, breast, liver, gynecologic, bladder, skin, pancreatic |

| Frozen Section Analysis | Histological evaluation of cryosectioned tissue under light microscopy | 20–60 min | Established “gold standard” for intraoperative diagnosis Provides morphological detail | Time-consuming Sampling errors Requires experienced pathologist Artifacts from cautery or freezing | Moderate (requires pathology lab and expertise) | Most tumor types |

| Fluorescence-Guided Resection (FGR, 5-ALA) | Tumor visualization via selective accumulation of 5-ALA metabolite (PpIX) under blue light | Require administration 3 h before the surgery | Real-time visualization of tumor margins Improve resection in GBM and HGG surgery | Limited to specific CNS tumor types Costly (EUR 1000 every dose in Europe) Variable fluorescence intensity | High (cost of 5-ALA and optical systems) | High-grade gliomas Other types of CNS tumors without FDA approval and mixed results |

| Intraoperative MRI (iMRI) | Real-time MRI imaging of residual tumor during surgery | >30–90 min | Real-time volumetric assessment; improves gross total resection | Very high cost Requires specialized equipment Prolongs surgery time Limited availability | Very High (infrastructure-intensive) | Brain, spine Can be used in all types of tumors |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Romeo, E.; Markopoulos, G.S.; Vartholomatos, G.; Voulgaris, S.; Alexiou, G.A. The Role of Intraoperative Flow Cytometry in Surgical Oncology: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2025, 17, 3898. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243898

Romeo E, Markopoulos GS, Vartholomatos G, Voulgaris S, Alexiou GA. The Role of Intraoperative Flow Cytometry in Surgical Oncology: A Systematic Review. Cancers. 2025; 17(24):3898. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243898

Chicago/Turabian StyleRomeo, Eleni, Georgios S. Markopoulos, George Vartholomatos, Spyridon Voulgaris, and George A. Alexiou. 2025. "The Role of Intraoperative Flow Cytometry in Surgical Oncology: A Systematic Review" Cancers 17, no. 24: 3898. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243898

APA StyleRomeo, E., Markopoulos, G. S., Vartholomatos, G., Voulgaris, S., & Alexiou, G. A. (2025). The Role of Intraoperative Flow Cytometry in Surgical Oncology: A Systematic Review. Cancers, 17(24), 3898. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243898