Inhibition of PD-L1/PD-1 Checkpoint Increases NK Cell-Mediated Killing of Melanoma Cells in the Presence of Interferon-Beta

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines and Culture

2.2. Isolation of Primary Human NK Cells

2.3. Reagents

2.4. Flow Cytometry

2.5. Analysis of Apoptotic and Proliferative Markers (Active Caspase-3 and Ki-67)

2.6. Calcein Release Assay

2.7. Analysis of NK Cell Cytotoxicity

2.8. Transfection of siRNA

2.9. Immunoblot

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

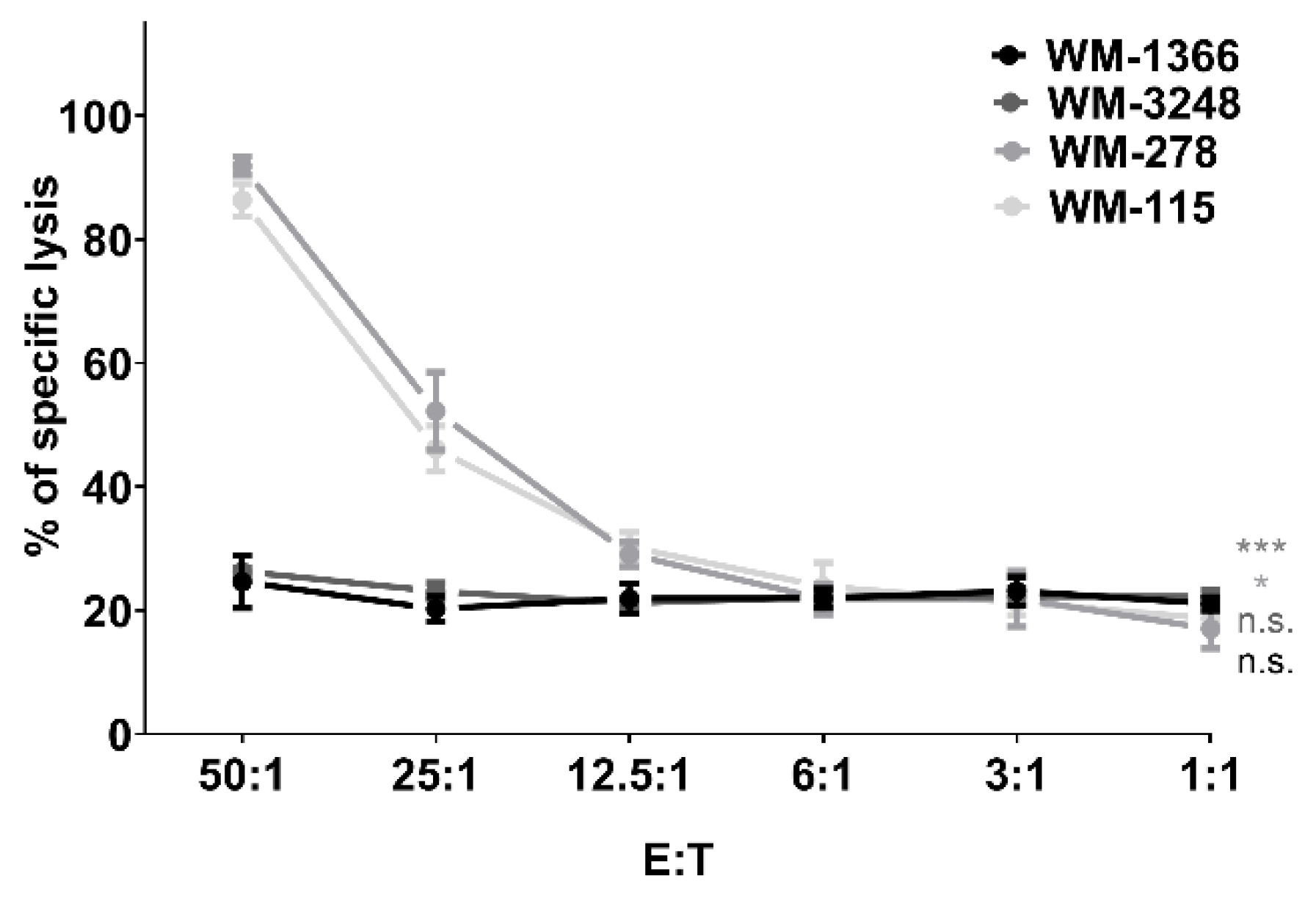

3.1. NK Cells Kill Melanoma Cells

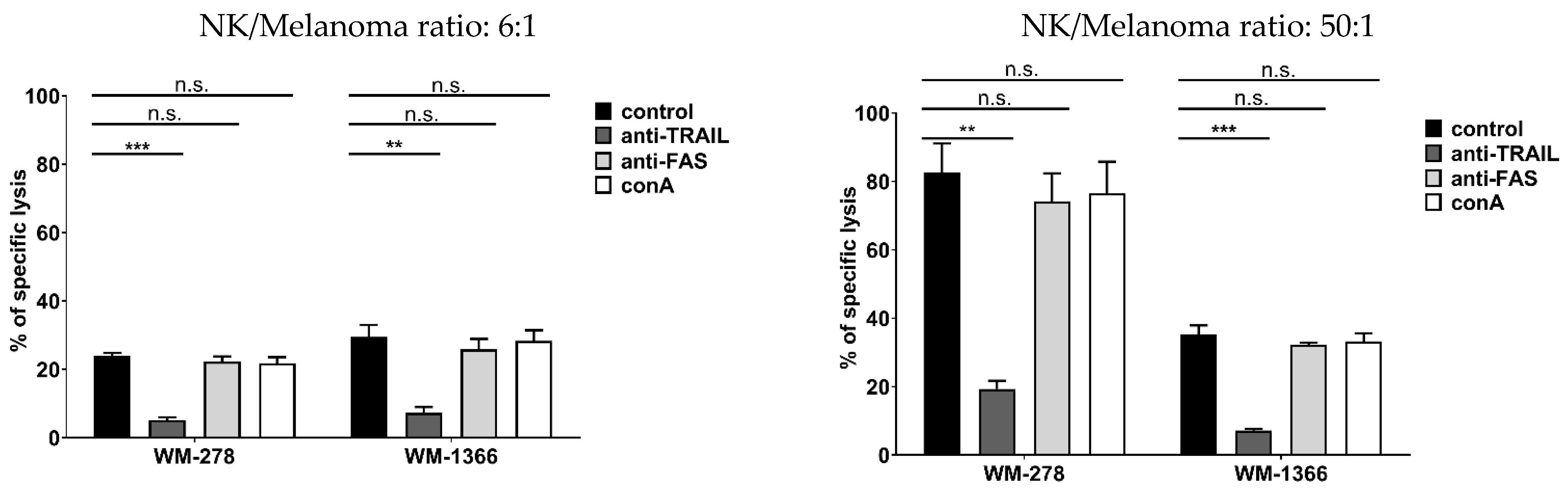

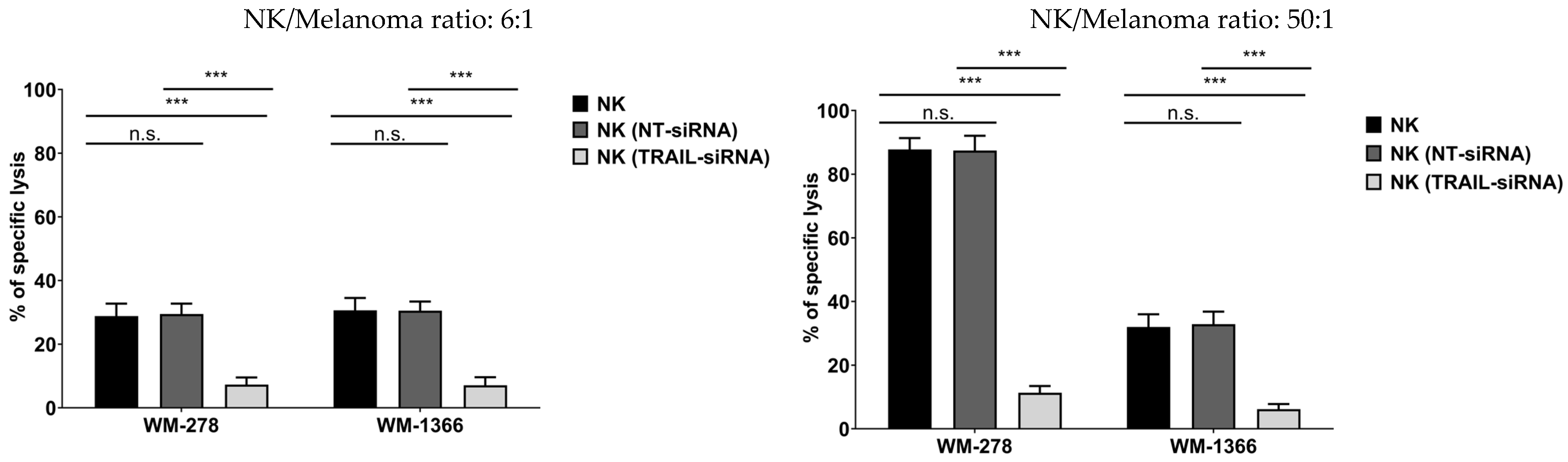

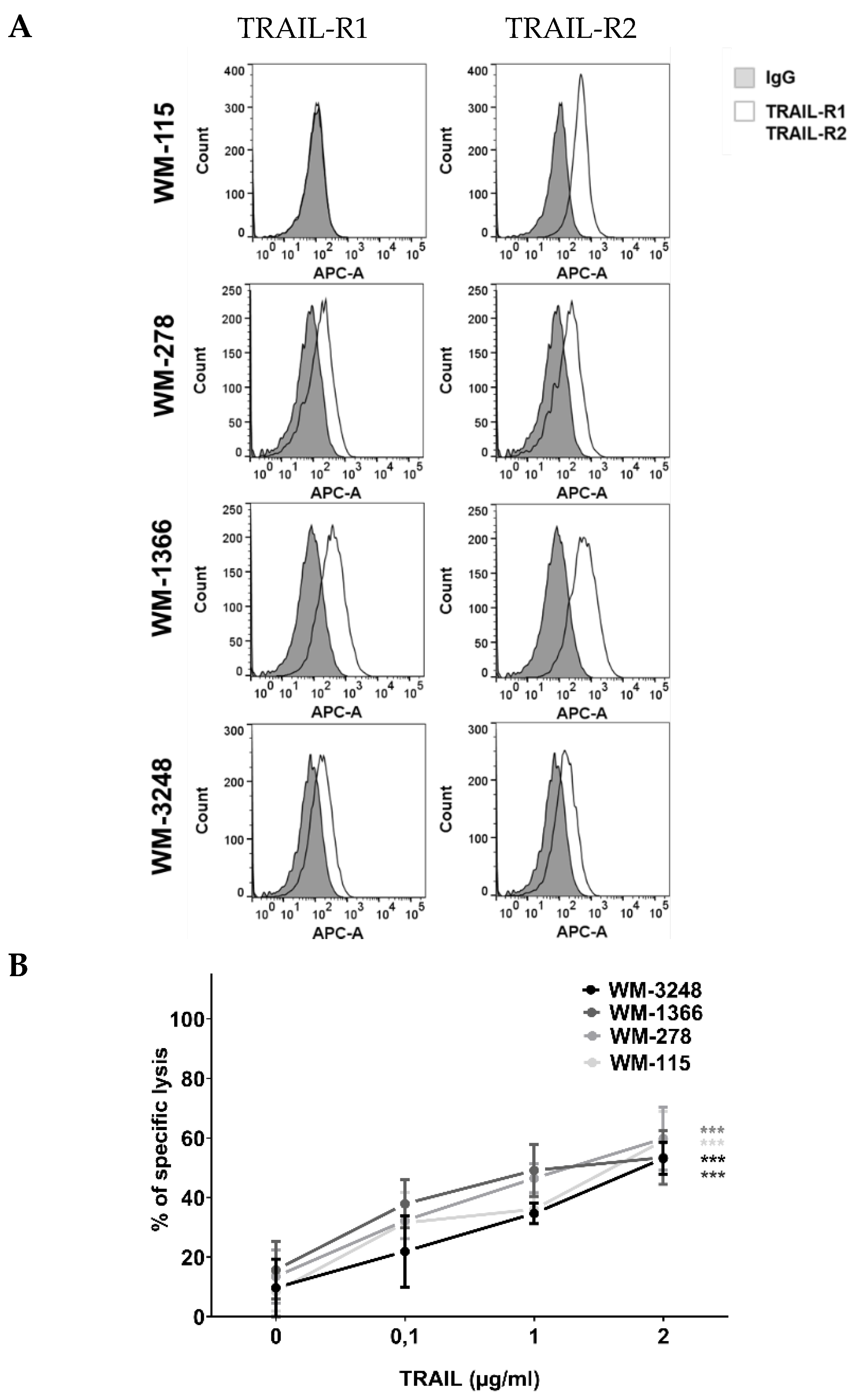

3.2. NK Cells Kill Melanoma Cells via TRAIL

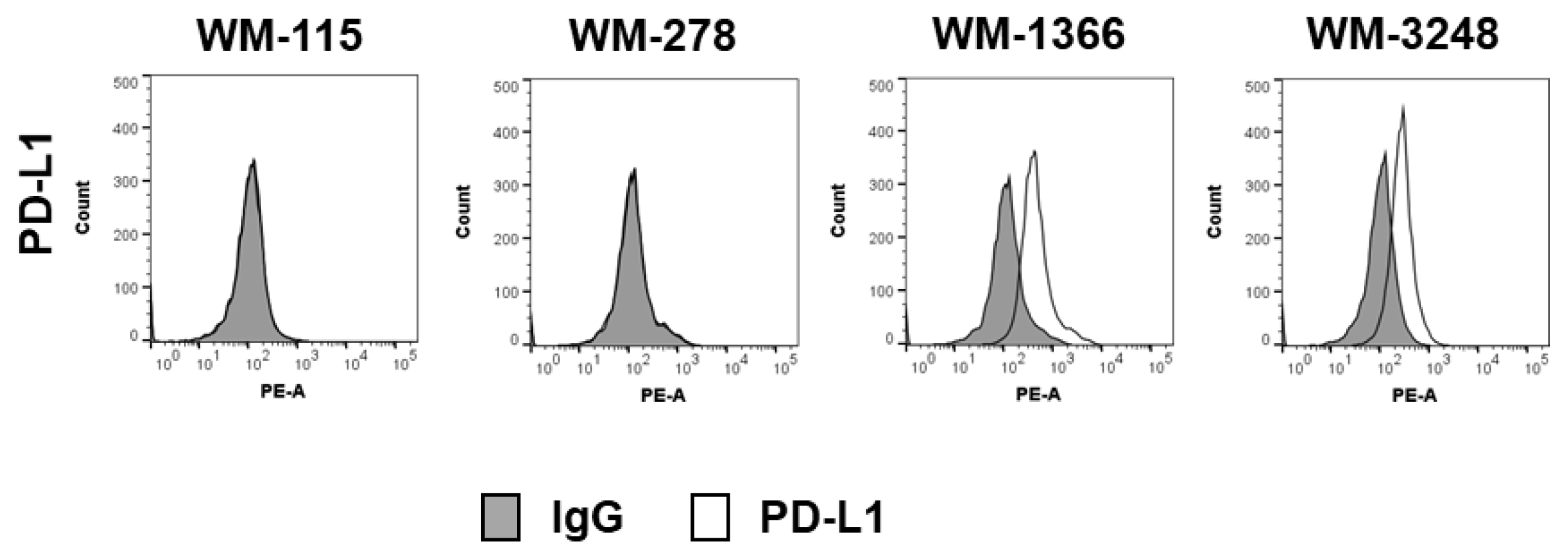

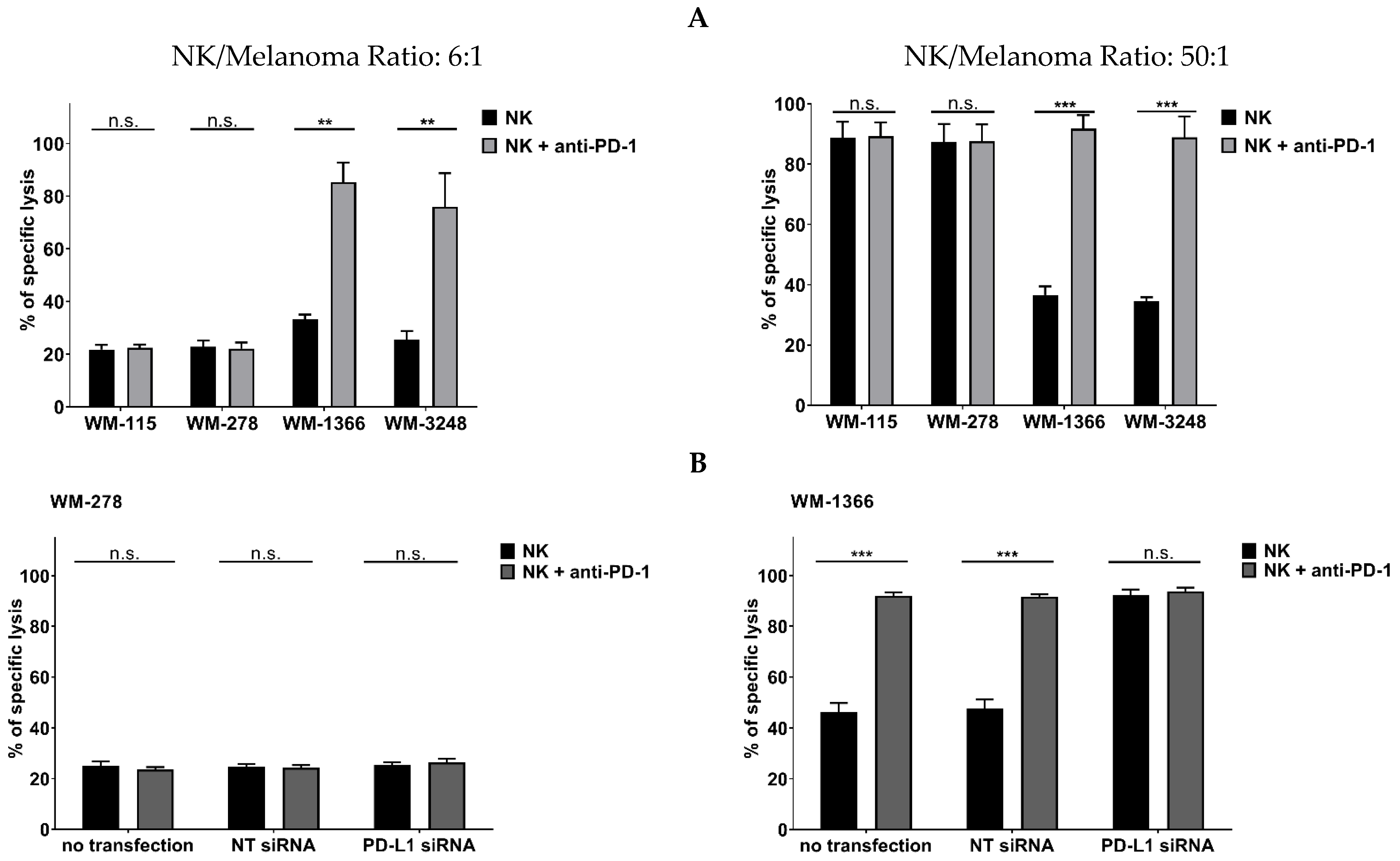

3.3. Role of Negative Checkpoint in NK Cell Killing Against Melanoma

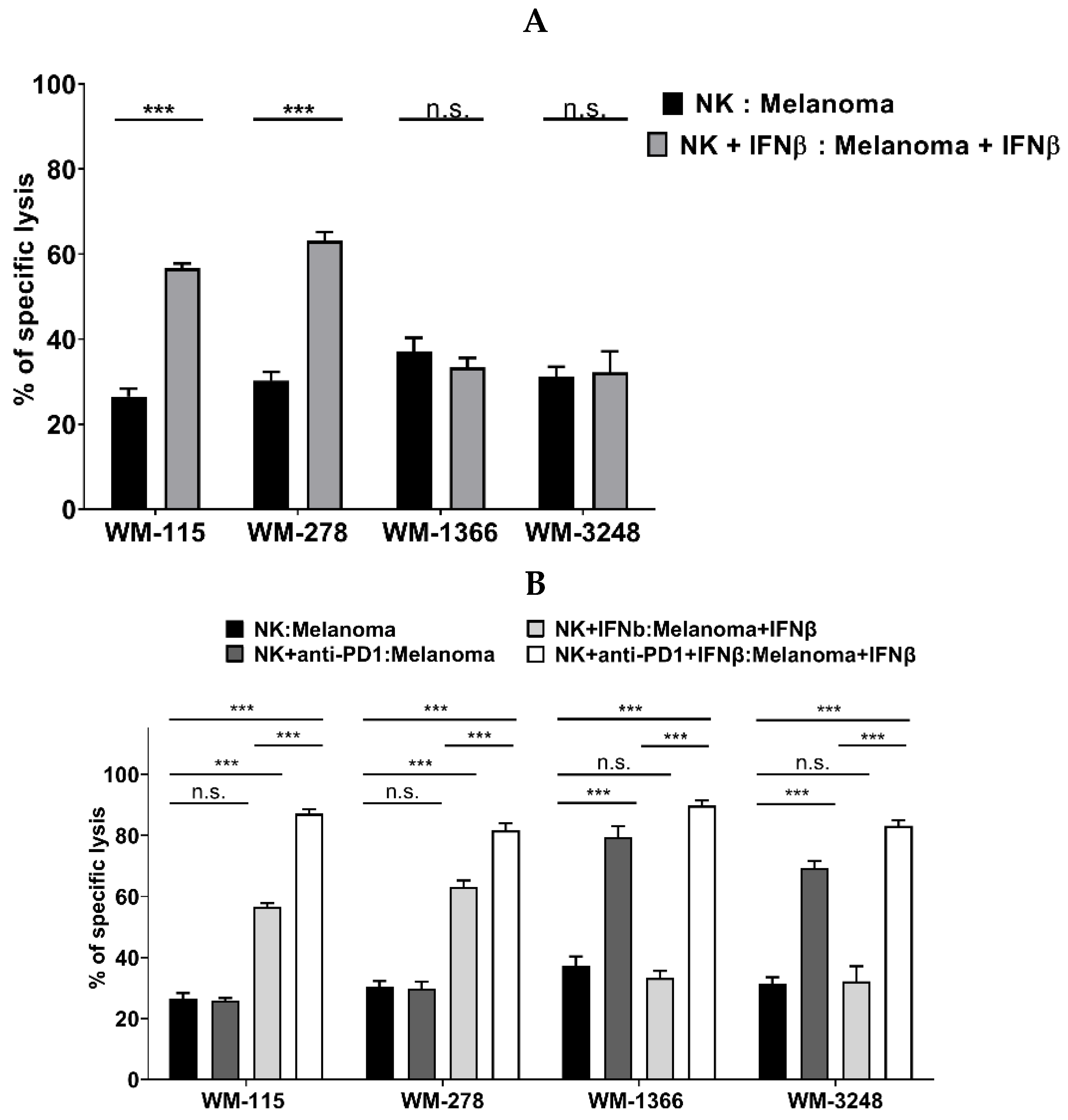

3.4. Role of IFNβ in NK Cell Killing of Melanoma

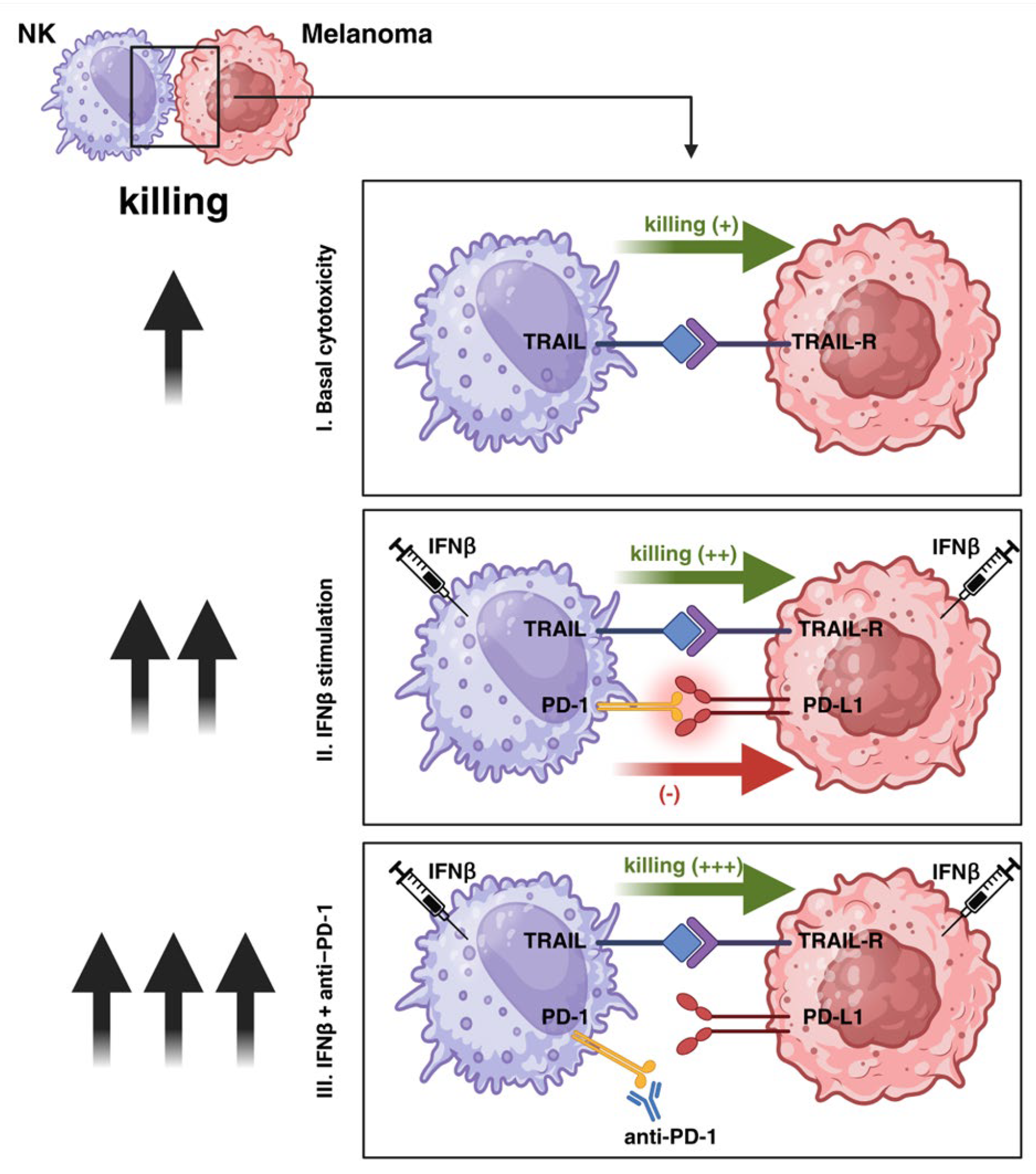

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferray, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, B.; Lopes, J.; Soares, P.; Populo, H. Melanoma treatment in review. Immunotargets Ther. 2018, 7, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, P.; Hauschild, A.; Robert, C.; Haanen, J.; Ascierto, P.; Larkin, J.; Dummer, R.; Garbe, C.; Testori, A.; Maio, M.; et al. Improved Survival with Vemurafenib in Melanoma with BRAF V600E Mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 2507–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsao, H.; Atkins, M.; Sober, A. Management of cutaneous melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 998–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdmann, F.; Lortet-Tieulent, J.; Schüz, J.; Zeeb, H.; Greinert, R.; Breitbart, E.; Bray, F. International trends in the incidence of malignant melanoma 1953–2008—Are recent generations at higher or lower risk? Int. J. Cancer 2013, 132, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coit, D.; Andtbacka, R.; Anker, C.; Bichakjian, C.; Carson, W.; Daud, A.; Dimaio, D.; Fleming, M.; Guild, V.; Halpern, A.; et al. Melanoma, version 2.2013: Featured updates to the NCCN guidelines. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2013, 11, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, L.; Garraway, L.; Fisher, D. Malignant melanoma: Genetics and therapeutics in the genomic era. Genes Dev. 2006, 20, 2149–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray-Schopfer, V.; Wellbrock, C.; Marais, R. Melanoma biology and new targeted therapy. Nature 2007, 445, 851–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, K.; Chen, S. Overcoming Immune Evasion in Melanoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdegaal, E. Adoptive cell therapy: A highly successful individualized therapy for melanoma with great potential for other malignancies. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2016, 39, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez, R.; Aptsiauri, R.; Del Campo, A.; Maleno, I.; Cabrera, T.; Ruiz-Cabello, F.; Garrido, F.; Garcia-Lora, A. HLA and melanoma: Multiple alterations in HLA class I and II expression in human melanoma cell lines from ESTDAB cell bank. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2009, 58, 1507–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakshmikanth, T.; Johansson, M. Current perspectives on immunomodulation of NK Cells in melanoma. In Melanoma in the Clinic—Diagnosis, Management and Complications of Malignancy; Mandi, M., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2011; pp. 133–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mirjacic Martinovic, K.; Babovic, N.; Dzodic, R.; Jurisic, V.; Tanic, N.; Konjevic, G. Decreased expression of NKG2D, NKp46, DNAM-1 receptors, and intracellular perforin and STAT-1 effector molecules in NK cells and their dim and bright subsets in metastatic melanoma patients. Melanoma Res. 2014, 24, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, I.; Gallois, A.; Jimenez-Baranda, S.; Khan, S.; Anderson, A.; Kuchroo, V.; Osman, I.; Bhardwaj, N. Reversal of NK-cell exhaustion in advanced melanoma by Tim-3 blockade. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2014, 2, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tam, Y.; Miyagawa, B.; Ho, V.; Klingemann, H. Immunotherapy of malignant melanoma in a SCID mouse model using the highly cytotoxic natural killer cell line NK-92. J. Hematother. 1999, 8, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vliet, A.; Georgoudaki, A.; Raimo, M.; Gruijl, T.; Spanholtz, J. Adoptive NK Cell Therapy: A Promising Treatment Prospect for Metastatic Melanoma. Cancers 2021, 13, 4722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wang, X.; Jin, T.; Tian, Y.; Dai, C.; Widarma, C.; Song, R.; Xu, F. Immune checkpoint molecules in natural killer cells as potential targets for cancer immunotherapy. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2020, 5, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckle, I.; Guillerey, C. Inhibitory Receptors and Immune Checkpoints Regulating Natural Killer Cell Responses to Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 4263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribas, A.; Hamid, O.; Daud, A.; Hodi, F.; Wolchok, J.; Kefford, R.; Joshua, A.; Patnaik, A.; Hwu, W.; Weber, J.; et al. Association of pembrolizumab with tumor response and survival among patients with advanced melanoma. JAMA 2016, 315, 1600–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, J.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Gonzalez, R.; Grob, J.; Rutkowski, P.; Lao, C.D.; Cowey, C.; Schadendorf, D.; Wagstaff, J.; Dummer, R.; et al. Five-Year Survival with Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1535–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoyagi, S.; Hata, H.; Homma, E.; Shimizu, H. Sequential local injection of low-dose interferon-beta for maintenance therapy in stage II and III melanoma: A single-institution matched case-control study. Oncology 2012, 82, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapprich, H.; Hagedorn, M. Intralesional therapy of metastatic spreading melanoma with beta-interferon. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2006, 4, 743–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimura, T.; Okuyama, R.; Ohtani, T.; Ito, Y.; Haga, T.; Hashimoto, A.; Aiba, S. Perilesional treatment of metastatic melanoma with interferon-beta. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2009, 34, 793–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makowska, A.; Braunschweig, T.; Denecke, B.; Shen, L.; Baloche, V.; Busson, P.; Kontny, U. Interferon β and anti-PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint blockade cooperate in NK cell-mediated killing of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Transl. Oncol. 2019, 12, 1237–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davar, D.; Wang, H.; Chauvin, J.; Pagliano, O.; Fourcade, J.; Ka, M.; Menna, C.; Rose, A.; Sander, C.; Borhani, A.; et al. Phase Ib/II Study of Pembrolizumab and Pegylated-Interferon Alfa-2b in Advanced Melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 3450–3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bairoch, A. The Cellosaurus, a cell line knowledge resource. J. Biomol. Tech. 2018, 29, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makowska, A.; Franzen, S.; Braunschweig, T.; Denecke, B.; Shen, L.; Baloche, V.; Busson, P.; Kontny, U. Interferon beta increases NK cell cytotoxicity against tumor cells in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma via tumor necrosis factor apoptosis-inducing ligand. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2019, 68, 1317–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanisenko, N.V.; König, C.; Hillert-Richter, L.K.; Feoktistova, M.A.; Pietkiewicz, S.; Richter, M.; Panayotova-Dimitrova, D.; Kaehne, T.; Lavrik, I.N. Oligomerised RIPK1 is the main core component of the CD95 necrosome. EMBO J. 2025, 44, 3231–3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivier, E.; Nunès, J.; Vély, F. Natural killer cell signaling pathways. Science 2004, 306, 1517–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla-Sarkar, M.; Leaman, D.; Jacobs, B.; Borden, E. IFN-β pretreatment sensitizes human melanoma cells to TRAIL/Apo2 ligand-induced apoptosis. J. Immunol. 2002, 169, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A.; Allavena, P.; Sica, A.; Balkwill, F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature 2008, 454, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorwald, V.; Davis, D.; Van Gulick, R.; Torphy, R.; Borgers, J.; Klarquist, J.; Couts, K.; Amato, C.; Cogswell, D.; Fujita, M.; et al. Circulating CD8(+) mucosal-associated invariant T cells correlate with improved treatment responses and overall survival in anti-PD-1-treated melanoma patients. Clin Transl Immunol. 2022, 11, e1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Galat, V.; Galat, Y.; Lee, Y.; Wainwright, D.; Wu, J. NK cell-based cancer immunotherapy: From basic biology to clinical development. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, D.R.; Cheng, J.Y.; Yan, W.Q.; Li, H.J. PD-L1/PD-1 blockage enhanced the cytotoxicity of natural killer cell on the non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) by granzyme B secretion. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2023, 25, 2373–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajor, M.; Graczyk-Jarzynka, A.; Marhelava, K.; Burdzinska, A.; Muchowicz, A.; Goral, A.; Zhylko, A.; Soroczynska, K.; Retecki, K.; Krawczyk, M.; et al. PD-L1 CAR effector cells induce self-amplifying cytotoxic effects against target cells. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e002500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, W.; Cao, X. The Involvement of TNF-α-Related Apoptosis-Inducing Ligand in the Enhanced Cytotoxicity of IFN-β-Stimulated Human Dendritic Cells to Tumor Cells. J. Immunol. 2001, 166, 5407–5415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, E.; Thomas, M.; Motoki, K.; Nakazawa, K.; Tahara, T.; Tomizuka, K.; Ishida, I.; Kataoka, S. Human normal hepatocytes are susceptible to apoptosis signal mediated by both TRAIL-R1 and TRAIL-R2. Cell Death Differ. 2004, 11, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walczak, H.; Degli-Esposti, M.; Johnson, R.; Smolak, P.; Waugh, J.; Boiani, N.; Timour, M.; Gerhart, M.; Schooley, K.; Smith, C.; et al. TRAIL-R2: A novel apoptosis-mediating receptor for TRAIL. EMBO J. 1997, 16, 5386–5397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, T.; Chin, W.; Jackson, G.; Lynch, D.; Kubin, M. Intracellular regulation of TRAIL-induced apoptosis in human melanoma cells. J. Immunol. 1998, 161, 2833–2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersey, P.; Zhang, X. How melanoma cells evade trail-induced apoptosis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2001, 1, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazaana, A.; Sano, E.; Yoshimura, S.; Makita, K.; Hara, H.; Yoshino, A.; Ueda, T. Promotion of TRAIL/Apo2L-induced apoptosis by low-dose interferon-β in human malignant melanoma cells. J. Cell Physiol. 2019, 234, 13510–13524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, L.; Aigner, P.; Stoiber, D. Type I Interferons and Natural Killer Cell Regulation in Cancer. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razaghi, A.; Durand-Dubief, M.; Brusselaers, N.; Björnstedt, M. Combining PD-1/PD-L1 blockade with type I interferon in cancer therapy. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1249330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J.; D’Angelo, S.; Minor, D.; Hodi, F.; Gutzmer, R.; Neyns, B.; Hoeller, C.; Khushalani, N.; Miller, W.; Lao, C.; et al. Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma who progressed after anti-CTLA-4 treatment (CheckMate 037): A randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bald, T.; Landsberg, J.; Lopez-Ramos, D.; Renn, M.; Glodde, N.; Jansen, P.; Gaffal, E.; Steitz, J.; Tolba, R.; Kalinke, U.; et al. Immune Cell–Poor Melanomas Benefit from PD-1 Blockade after Targeted Type I IFN Activation. Cancer Discov. 2014, 4, 674–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achkar, T.; Tarhini, A.A. The use of immunotherapy in the treatment of melanoma. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2017, 10, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Makowska, A.; Shen, L.; Nothbaum, C.; Panayotova-Dimitrova, D.; Feoktistova, M.; Yazdi, A.S.; Kontny, U. Inhibition of PD-L1/PD-1 Checkpoint Increases NK Cell-Mediated Killing of Melanoma Cells in the Presence of Interferon-Beta. Cancers 2025, 17, 3899. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243899

Makowska A, Shen L, Nothbaum C, Panayotova-Dimitrova D, Feoktistova M, Yazdi AS, Kontny U. Inhibition of PD-L1/PD-1 Checkpoint Increases NK Cell-Mediated Killing of Melanoma Cells in the Presence of Interferon-Beta. Cancers. 2025; 17(24):3899. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243899

Chicago/Turabian StyleMakowska, Anna, Lian Shen, Christina Nothbaum, Diana Panayotova-Dimitrova, Maria Feoktistova, Amir S. Yazdi, and Udo Kontny. 2025. "Inhibition of PD-L1/PD-1 Checkpoint Increases NK Cell-Mediated Killing of Melanoma Cells in the Presence of Interferon-Beta" Cancers 17, no. 24: 3899. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243899

APA StyleMakowska, A., Shen, L., Nothbaum, C., Panayotova-Dimitrova, D., Feoktistova, M., Yazdi, A. S., & Kontny, U. (2025). Inhibition of PD-L1/PD-1 Checkpoint Increases NK Cell-Mediated Killing of Melanoma Cells in the Presence of Interferon-Beta. Cancers, 17(24), 3899. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243899