Comparing Isocitrate Dehydrogenase Inhibitors with Procarbazine, Lomustine, and Vincristine Chemotherapy for Oligodendrogliomas

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

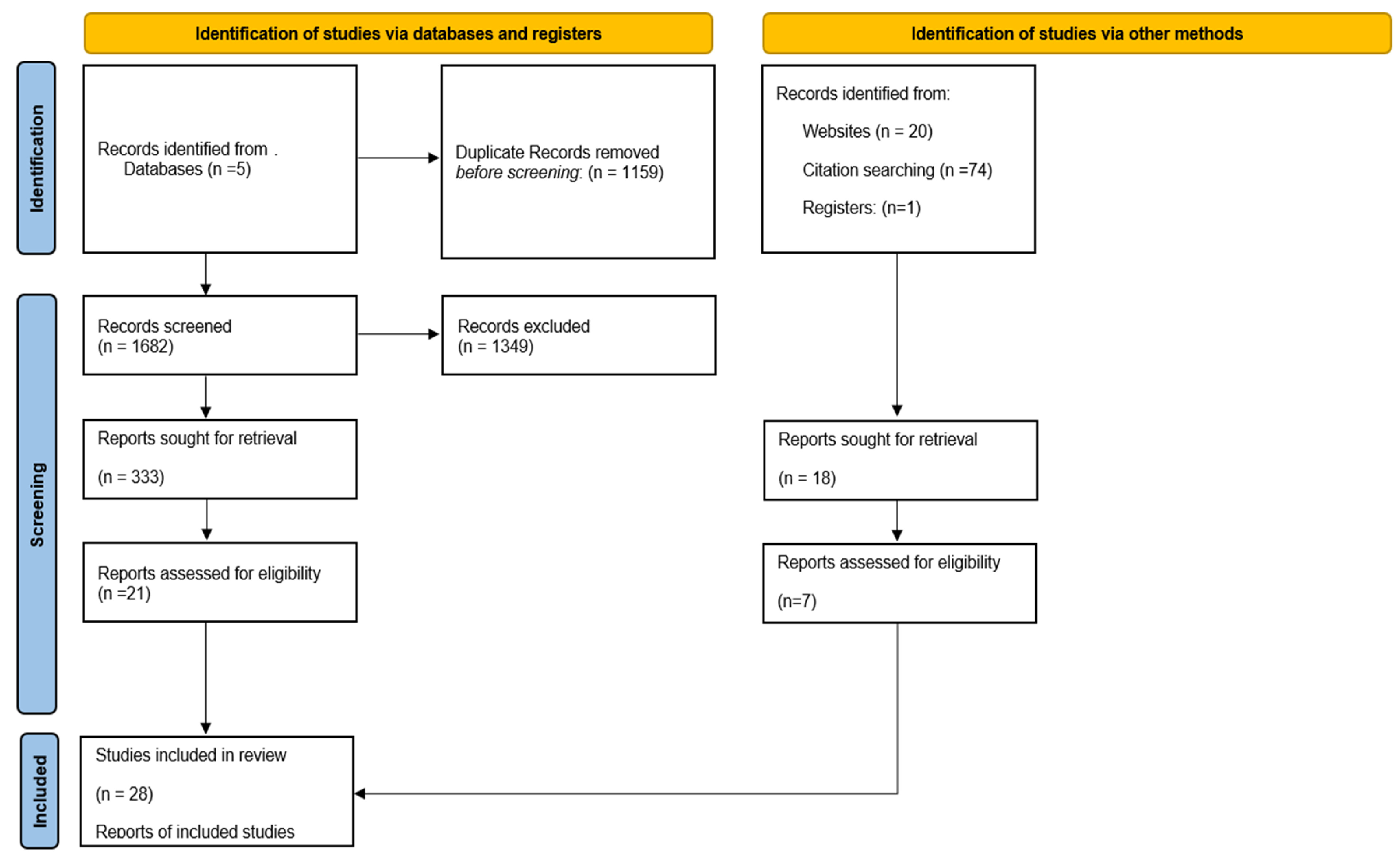

3.1. Study Selection

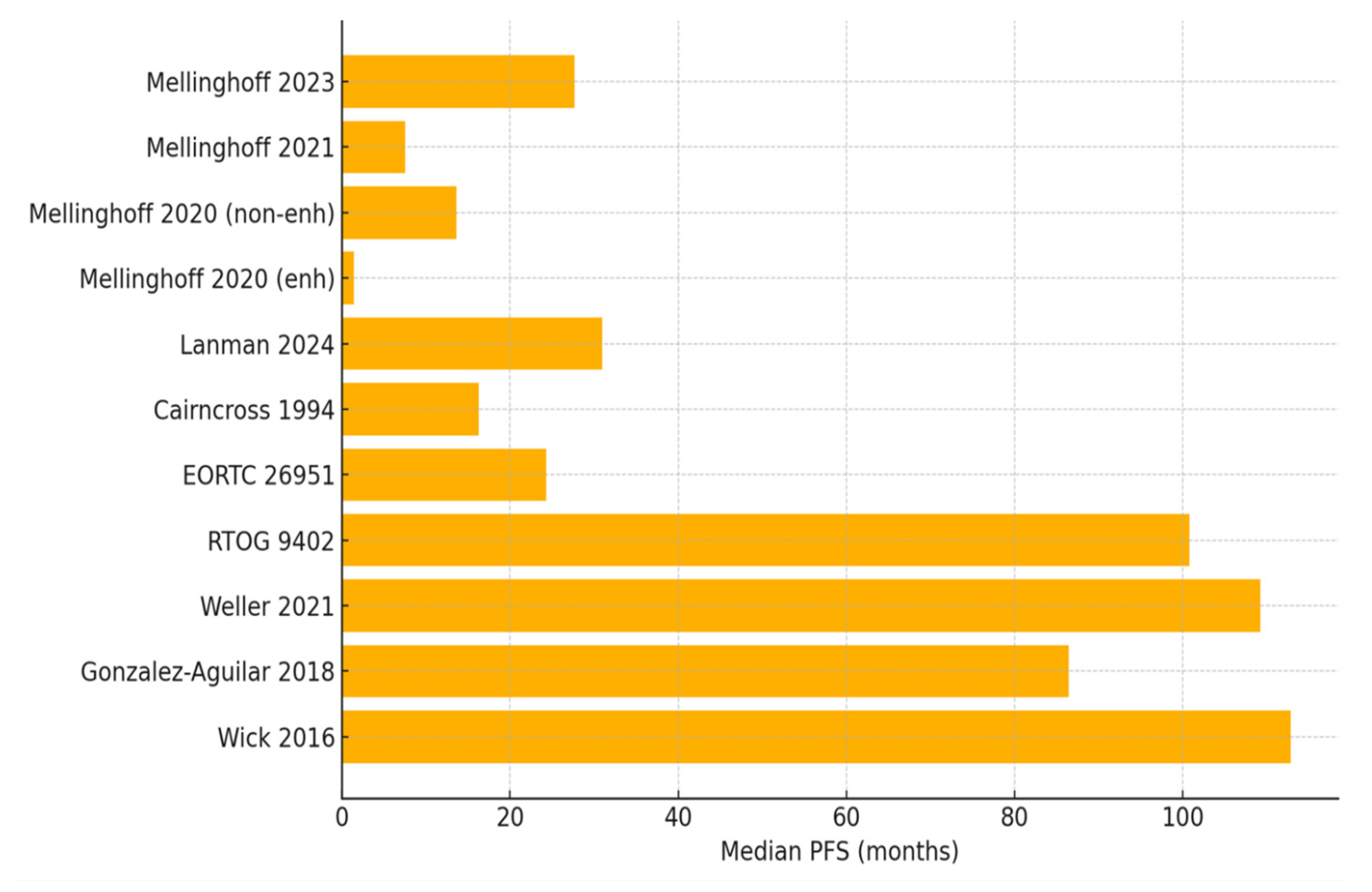

3.2. Treatment Efficacy Profiles

3.2.1. Evidence Profile of IDH Inhibitors

3.2.2. Evidence Profile of PCV Chemotherapy

3.3. Current Treatment Guidelines

3.4. Treatment Toxicity Profiles

3.4.1. Toxicity Profile of IDH Inhibitors

3.4.2. Toxicity Profile of PCV Chemotherapy

3.5. Quality of Life and Functional Outcomes

3.6. Resistance Mechanisms and Clinical Implementation

3.6.1. IDH Inhibitors

3.6.2. PCV Chemotherapy

3.7. Limitations of Current Evidence

4. Discussion

4.1. Efficacy Contextualization

4.2. Impact of Study Design Heterogeneity on Interpretation

4.3. Toxicity and Patient-Reported Outcome Gaps

4.4. Biomarker-Driven Selection

4.5. Our Clinical and Scientific Recommendations Based on Existing Data

4.5.1. Clinical Decision Framework

- For MGMT methylated tumors in patients with a good performance status: PCV plus radiation remains strongly recommended per the 2025 ASCO-SNO guidelines given the proven OS benefit.

- For patients where radiation/chemotherapy has been deferred and not indicated postoperatively: Vorasidenib may be offered (conditional recommendation 1.2.1) based on INDIGO trial.

- For MGMT unmethylated tumors or patients with poor PCV tolerance: Consider IDH inhibitor, acknowledging uncertain long-term benefits.

- For non-enhancing disease meeting the INDIGO criteria: Discuss both options, emphasizing PCV’s proven OS versus IDH inhibitor’s tolerability.

- For patients with enhancement or grade 3 disease: No vorasidenib recommendation; PCV plus radiation remains standard.

- For progression post-PCV: IDH inhibitor reasonable given different mechanism of action.

- For progression post-IDH inhibitor: Limited data; consider PCV if previously untreated.

4.5.2. Agenda for Future Research

- Head-to-head randomized trial comparing IDH inhibitors versus PCV (phase III, n = 500, primary endpoint OS, projected completion 2032).

- Standardized PRO collection using EORTC QLQ-C30/BN20 in all trials (implementation feasible immediately).

- Optimal sequencing trial: upfront IDH inhibitor→PCV versus PCV→IDH inhibitor (phase II, n = 200, projected completion 2030).

- Biomarker-driven patient selection beyond MGMT status (multi-institutional discovery cohort, n = 1000, validation n = 500).

- Long-term neurocognitive outcomes (longitudinal cohort with annual testing, n = 300, 10-year follow-up).

- Cost-effectiveness modeling incorporating quality-adjusted life year analyses (decision analysis study).

- Combination strategies (phase I/II dose-finding, multiple arms).

- Enhancement status validation as predictive biomarker (imaging-stratified trial, n = 150).

- Resistance mechanism characterization from clinical samples (translational study embedded in trials).

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Low, J.T.; Ostrom, Q.T.; Cioffi, G.; Neff, C.; A Waite, K.; Kruchko, C.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. Primary brain and other central nervous system tumors in the United States (2014–2018): A summary of the CBTRUS statistical report for clinicians. Neuro-Oncol. Pract. 2022, 9, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torp, S.H.; Solheim, O.; Skjulsvik, A.J. The WHO 2021 Classification of Central Nervous System tumours: A practical update on what neurosurgeons need to know—A minireview. Acta Neurochir. 2022, 164, 2453–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, K.; Zhang, S.-Y.; Li, L.-W.; Zou, Y.-F.; Wu, B.; Xia, L.; Sun, C.-X. Prognosis of Oligodendroglioma Patients Stratified by Age: A SEER Population-Based Analysis. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2021, 14, 9523–9536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Cote, D.J.; Ascha, M.; Kruchko, C.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. Adult Glioma Incidence and Survival by Race or Ethnicity in the United States from 2000 to 2014. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 1254–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.C.; Ma, C.; Yip, S. From Theory to Practice: Implementing the WHO 2021 Classification of Adult Diffuse Gliomas in Neuropathology Diagnosis. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oligodendroglioma and Other IDH-Mutated Tumors: Diagnosis and Treatment. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/rare-brain-spine-tumor/tumors/oligodendroglioma (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- van den Bent, M.J.; Dubbink, H.J.; Sanson, M.; Van Der Lee-Haarloo, C.R.; Hegi, M.; Jeuken, J.W.; Ibdaih, A.; Brandes, A.A.; Taphoorn, M.J.; Frenay, M.; et al. MGMT Promoter Methylation Is Prognostic but Not Predictive for Outcome to Adjuvant PCV Chemotherapy in Anaplastic Oligodendroglial Tumors: A Report From EORTC Brain Tumor Group Study 26951. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 5881–5886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassman, A.B.; Hoang-Xuan, K.; Polley, M.-Y.C.; Brandes, A.A.; Cairncross, J.G.; Kros, J.M.; Ashby, L.S.; Taphoorn, M.J.; Souhami, L.; Dinjens, W.N.; et al. Joint Final Report of EORTC 26951 and RTOG 9402: Phase III Trials with Procarbazine, Lomustine, and Vincristine Chemotherapy for Anaplastic Oligodendroglial Tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 2539–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, L.; White, D.W.; Gross, S.; Bennett, B.D.; Bittinger, M.A.; Driggers, E.M.; Fantin, V.R.; Jang, H.G.; Jin, S.; Keenan, M.C.; et al. Cancer-associated IDH1 mutations produce 2-hydroxyglutarate. Nature 2009, 462, 739–744, Erratum in Nature 2010, 465, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellinghoff, I.K.; Bent, M.J.v.D.; Blumenthal, D.T.; Touat, M.; Peters, K.B.; Clarke, J.; Mendez, J.; Yust-Katz, S.; Welsh, L.; Mason, W.P.; et al. Vorasidenib in IDH1- or IDH2-Mutant Low-Grade Glioma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellinghoff, I.K.; Penas-Prado, M.; Peters, K.B.; Burris, H.A.; Maher, E.A.; Janku, F.; Cote, G.M.; de la Fuente, M.I.; Clarke, J.L.; Ellingson, B.M.; et al. Vorasidenib, a Dual Inhibitor of Mutant IDH1/2, in Recurrent or Progressive Glioma; Results of a First-in-Human Phase I Trial. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 4491–4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellinghoff, I.K.; Ellingson, B.M.; Touat, M.; Maher, E.; De La Fuente, M.I.; Holdhoff, M.; Cote, G.M.; Burris, H.; Janku, F.; Young, R.J.; et al. Ivosidenib in Isocitrate Dehydrogenase 1–Mutated Advanced Glioma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 3398–3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanman, T.A.; Youssef, G.; Huang, R.; Rahman, R.; DeSalvo, M.; Flood, T.; Hassanzadeh, E.; Lang, M.; Lauer, J.; Potter, C.; et al. Ivosidenib for the treatment of IDH1-mutant glioma, grades 2–4: Tolerability, predictors of response, and outcomes. Neuro-Oncol. Adv. 2024, 7, vdae227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cairncross, G.; Macdonald, D.; Ludwin, S.; Lee, D.; Cascino, T.; Buckner, J.; Fulton, D.; Dropcho, E.; Stewart, D.; Schold, C. Chemotherapy for anaplastic oligodendroglioma. National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 1994, 12, 2013–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bent, M.J.v.D.; Brandes, A.A.; Taphoorn, M.J.; Kros, J.M.; Kouwenhoven, M.C.; Delattre, J.-Y.; Bernsen, H.J.; Frenay, M.; Tijssen, C.C.; Grisold, W.; et al. Adjuvant Procarbazine, Lomustine, and Vincristine Chemotherapy in Newly Diagnosed Anaplastic Oligodendroglioma: Long-Term Follow-Up of EORTC Brain Tumor Group Study 26951. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairncross, G.; Wang, M.; Shaw, E.; Jenkins, R.; Brachman, D.; Buckner, J.; Fink, K.; Souhami, L.; Laperriere, N.; Curran, W.; et al. Phase III Trial of Chemoradiotherapy for Anaplastic Oligodendroglioma: Long-Term Results of RTOG 9402. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, J.; Katzendobler, S.; Karschnia, P.; Lietke, S.; Egensperger, R.; Thon, N.; Weller, M.; Suchorska, B.; Tonn, J.-C. PCV chemotherapy alone for WHO grade 2 oligodendroglioma: Prolonged disease control with low risk of malignant progression. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2021, 153, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacimi, S.E.O.; Dehais, C.; Feuvret, L.; Chinot, O.; Carpentier, C.; Bronnimann, C.; Vauleon, E.; Djelad, A.; Moyal, E.C.-J.; Langlois, O.; et al. Survival Outcomes Associated with First-Line Procarbazine, CCNU, and Vincristine or Temozolomide in Combination with Radiotherapy in IDH-Mutant 1p/19q-Codeleted Grade 3 Oligodendroglioma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Aguilar, A.; Reyes-Moreno, I.; Peiro-Osuna, R.P.; Hernandez-Hernandez, A.; Gutierrez-Aceves, A.; Santos-Zambrano, J.; Guerrero-Juarez, V.; Lopez-Martinez, M.; Castro-Martinez, E. Radioterapia más temozolomida o PCV en pacientes con oligodendroglioma anaplásico con codeleción 1p19q. Rev. De Neurol. 2018, 67, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wick, W.; Roth, P.; Hartmann, C.; Hau, P.; Nakamura, M.; Stockhammer, F.; Sabel, M.C.; Wick, A.; Koeppen, S.; Ketter, R.; et al. Long-term analysis of the NOA-04 randomized phase III trial of sequential radiochemotherapy of anaplastic glioma with PCV or temozolomide. Neuro-Oncology 2016, 18, 1529–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakeley, J.; Mohile, N.A.; Messersmith, H.; Lassman, A.B.; Schiff, D.; Therapy for Diffuse Astrocytic and Oligodendroglial Tumors in Adults Guideline Expert Panel. Therapy for Diffuse Astrocytic and Oligodendroglial Tumors in Adults: ASCO-SNO Guideline Rapid Recommendation Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 2129–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Fuente, M.I.; Colman, H.; Rosenthal, M.; A Van Tine, B.; Levacic, D.; Walbert, T.; Gan, H.K.; Vieito, M.; Milhem, M.M.; Lipford, K.; et al. Olutasidenib (FT-2102) in patients with relapsed or refractory IDH1-mutant glioma: A multicenter, open-label, phase Ib/II trial. Neuro-Oncology 2022, 25, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natsume, A.; Arakawa, Y.; Narita, Y.; Sugiyama, K.; Hata, N.; Muragaki, Y.; Shinojima, N.; Kumabe, T.; Saito, R.; Motomura, K.; et al. The first-in-human phase I study of a brain-penetrant mutant IDH1 inhibitor DS-1001 in patients with recurrent or progressive IDH1-mutant gliomas. Neuro-Oncology 2022, 25, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincon-Torroella, J.; Rakovec, M.; Kalluri, A.L.; Jiang, K.; Weber-Levine, C.; Parker, M.; Raj, D.; Materi, J.; Sepehri, S.; Ferres, A.; et al. Impact of upfront adjuvant chemoradiation on survival in patients with molecularly defined oligodendroglioma: The benefits of PCV over TMZ. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2024, 171, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabouret, E.; Reyes-Botero, G.; Dehais, C.; Daros, M.; Barrie, M.; Matta, M.; Petrirena, G.; Autran, D.; Duran, A.; Bequet, C.; et al. Relationships Between Dose Intensity, Toxicity, and Outcome in Patients with Oligodendroglial Tumors Treated with the PCV Regimen. Anticancer Res. 2015, 35, 2901–2908. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, S.; Kim, Y.I.; Shin, J.Y.; Park, J.-S.; Yoo, C.; Lee, Y.S.; Hong, Y.-K.; Jeun, S.-S.; Yang, S.H. Clinical feasibility of modified procarbazine and lomustine chemotherapy without vincristine as a salvage treatment for recurrent adult glioma. Oncol. Lett. 2022, 23, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitzer, A.; Gritsch, S.; Nomura, M.; Jucht, A.; Fortin, J.; Raviram, R.; Weisman, H.R.; Castro, L.N.G.; Druck, N.; Chanoch-Myers, R.; et al. Mutant IDH inhibitors induce lineage differentiation in IDH-mutant oligodendroglioma. Cancer Cell 2024, 42, 904–914.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Bent, M.J.; Kros, J.M.; Heimans, J.J.; Pronk, L.C.; Van Groeningen, C.J.; Krouwer, H.G.; Taphoorn, M.J.; A Zonnenberg, B.; Tijssen, C.C.; Twijnstra, A.; et al. Response rate and prognostic factors of recurrent oligodendroglioma treated with procarbazine, CCNU, and vincristine chemotherapy. Neurology 1998, 51, 1140–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oltvai, Z.N.; Harley, S.E.; Koes, D.; Michel, S.; Warlick, E.D.; Nelson, A.C.; Yohe, S.; Mroz, P. Assessing acquired resistance to IDH1 inhibitor therapy by full-exon IDH1 sequencing and structural modeling. Mol. Case Stud. 2021, 7, a006007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahon, J.T.; Studer, M.; Ulrich, B.; Barbero, J.M.R.; Pradilla, I.; Palacios-Ariza, M.A.; Pradilla, G. Circulating Tumor DNA in Adults with Glioma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Biomarker Performance. Neurosurgery 2022, 91, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahebjam, S.; McNamara, M.G.; Mason, W.P. Emerging biomarkers in anaplastic oligodendroglioma: Implications for clinical investigation and patient management. CNS Oncol. 2013, 2, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, A. New Standard of Care for Anaplastic Oligodendroglial Tumors with 1p/19q Codeletions. Available online: https://ascopost.com/issues/july-1-2012/new-standard-of-care-for-anaplastic-oligodendroglial-tumors-with-1p19q-codeletions.aspx (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Szylberg, M.; Sokal, P.; Śledzińska, P.; Bebyn, M.; Krajewski, S.; Szylberg, Ł.; Szylberg, A.; Szylberg, T.; Krystkiewicz, K.; Birski, M.; et al. MGMT Promoter Methylation as a Prognostic Factor in Primary Glioblastoma: A Single-Institution Observational Study. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinslow, C.J.; Mercurio, A.; Kumar, P.; Rae, A.I.; Siegelin, M.D.; Grinband, J.; Taparra, K.; Upadhyayula, P.S.; McKhann, G.M.; Sisti, M.B.; et al. Association of MGMT Promoter Methylation with Survival in Low-grade and Anaplastic Gliomas After Alkylating Chemotherapy. JAMA Oncol. 2023, 9, 919–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, V.P.; Ichimura, K.; Di, Y.; Pearson, D.; Chan, R.; Thompson, L.C.; Gabe, R.; Brada, M.; Stenning, S.P. Prognostic and predictive markers in recurrent high grade glioma; results from the BR12 randomised trial. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2014, 2, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.; Ambrogi, F.; Gay, L.; Gallucci, M.; Nibali, M.C.; Leonetti, A.; Puglisi, G.; Sciortino, T.; Howells, H.; Riva, M.; et al. Is supratotal resection achievable in low-grade gliomas? Feasibility, putative factors, safety, and functional outcome. J. Neurosurg. 2020, 132, 1692–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, E.H.; Zhang, P.; Shaw, E.G.; Buckner, J.C.; Barger, G.R.; Bullard, D.E.; Mehta, M.P.; Gilbert, M.R.; Brown, P.D.; Stelzer, K.J.; et al. Comprehensive Genomic Analysis in NRG Oncology/RTOG 9802: A Phase III Trial of Radiation Versus Radiation Plus Procarbazine, Lomustine (CCNU), and Vincristine in High-Risk Low-Grade Glioma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 3407–3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verburg, N.; Koopman, T.; Yaqub, M.M.; Hoekstra, O.S.; A Lammertsma, A.; Barkhof, F.; Pouwels, P.J.W.; Reijneveld, J.C.; Heimans, J.J.; Rozemuller, A.J.M.; et al. Improved detection of diffuse glioma infiltration with imaging combinations: A diagnostic accuracy study. Neuro-Oncology 2019, 22, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, A.; Hachem, L.D.; Mansouri, S.; Nassiri, F.; Laperriere, N.J.; Xia, D.; I Lindeman, N.; Wen, P.Y.; Chakravarti, A.; Mehta, M.P.; et al. MGMT promoter methylation status testing to guide therapy for glioblastoma: Refining the approach based on emerging evidence and current challenges. Neuro-Oncology 2018, 21, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewersdorf, J.P.; Patel, K.K.; Goshua, G.; Shallis, R.M.; Podoltsev, N.A.; Stahl, M.; Stein, E.M.; Huntington, S.F.; Zeidan, A.M. Cost-effectiveness of azacitidine and ivosidenib in newly diagnosed older, intensive chemotherapy-ineligible patients with IDH1-mutant acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk. Lymphoma 2022, 64, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Treatment | Population (Gliomas) | Median PFS | Median OS | ORR | DCR | Study Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mellinghoff et al., 2023 [10] | Vorasidenib vs. Placebo | n = 331 (Oligo = 172) | 27.7 vs. 11.1 mo | NR | 10.7% vs. 2.5% | 94.0% vs. 91.4% | Phase III RCT (ongoing) | Included both oligodendroglioma and astrocytoma patients; efficacy consistent across histologies. |

| Mellinghoff et al., 2021 [11] | Vorasidenib | n = 52 (Oligo = 16) (22 non-enh; 30 enh) | 36.8 mo (non-enh); 3.6 mo (enh) | NR | ORR: 18.2% (non-enh); 0% (enh) | non-enh: 90.9%; enh: 56.7% | Phase I | Non-enhancing tumors had better outcomes. |

| Mellinghoff et al., 2020 [12] | Ivosidenib | n = 66 total (Oligo ≥ 3) (35 non-enh; 31 enh) | 13.6 mo (non-enh); 1.4 mo (enh) | NR | 2.9% (non-enh) 0% (enh) | 88.6% (non-enh) 45.2% (enh) | Phase I | Non-enhancing tumors had better outcomes. |

| Lanman et al., 2024 [13] | Ivosidenib | n = 74 total (Oligo = 39) | 31 mo | NR | 7.7% | 82% | Retrospective | Non-enhancing better outcomes. |

| Cairncross et al., 1994 [14] | PCV | n = 24 oligo | 16.3 mo | NR | 75% | 92% | Prospective phase II | High initial response rate. |

| EORTC 26951 [15] | RT vs. RT + PCV | Phase III; n = 368 anaplastic oligodendroglial tumors (1p/19q-codeleted = 80) | 13.2 vs. 24.3 | 30.6 vs. 42.3 | NR | NR | Phase III RCT | Long-term survival benefit. |

| RTOG 9402 [16] | RT vs. RT + PCV | n = 291 AO/AOA (known codeleted: 59) | 2.9 vs. 8.4 y (specifically codeleted) | 7.3 y vs. 14.7 y | NR | NR | Phase III RCT | Codeleted subgroup favored PCV. |

| Weller et al., 2021 [17] | PCV, TMZ, Surgery, or Wait and Scan | n = 142 Oligos (PCV n = 30) | PCV: 9.1 y | NR | NR | ~100% (PCV) | Retrospective cohort | PCV group showed the longest PFS. |

| Kacimi et al., 2025 [18] | RT + PCV vs. RT + TMZ | n = 305 Oligo | 10 yr PFS: 67% (PCV) vs. 35% (TMZ) | 10 yr OS: 72% (PCV) vs. 60% (TMZ) | NR | NR | Prospective observational | PCV/RT significantly improved OS and PFS. |

| Gonzalez-Aguilar et al., 2018 [19] | RT + PCV vs. RT + TMZ | n = 48 Oligo | PCV: 7.2 y; TMZ: 6.1 y | PCV: 10.6 y; TMZ: 9.2 y | PCV: 80.9%, TMZ: 70.3% | NR | Retrospective | PCV/RT significantly improved OS and PFS. |

| Wick et al., 2016 (NOA-04) [20] | Initial RT vs. initial PCV vs. initial TMZ | n = 274 anaplastic gliomas (Oligo = 68) | RT: 8.67 y; PCV: 9.4 y; TMZ: 4.46 y | RT: n/r (9.95–n/r); PCV: n/r (8.19–n/r) y; TMZ: 8.09 y | NR | NR | Phase III RCT | In IDH-mut/1p19q-codel tumors, PCV showed longer PFS than TMZ. |

| Study | Treatment | Population Gliomas | Grade ≥ 3 AE Rate | Common AEs | Discontinuation Rate | Evidence Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mellinghoff et al., 2023 [10] | Vorasidenib vs. Placebo | Oligo n = 172 | 22.8% vs. 13.5% | LT ↑, AST ↑, GGT ↑ | 31.5% (Vora) vs. 57.1% (Placebo) | Phase III RCT | Mostly liver enzyme elevations |

| Mellinghoff et al., 2020 [12] | Ivosidenib | n = 66 total (Oligo ≥ 3) (35 non-enh; 31 enh) | 19.7% overall | Headache, Nausea, Fatigue, Vomiting, etc. | 77.3% | Phase I | Most stopped due to progression |

| De La Fuente et al., 2022 [22] | Olutasidenib | n = 26 (Oligo = 6) | 42% | Nausea, Fatigue, Diarrhea, Vomiting, etc. | 77% | Phase Ib/II Prospective clinical trial | 50% dropped out of study due to death |

| Natsume et al., 2022 [23] | DS-100 | n = 47 (Oligo = 15) | 42.6% | Skin hyperpigmentation, diarrhea, pruritus, etc. | 83% | Phase I dose-escalation | Many discontinued due to progression |

| Lanman et al., 2024 [13] | Ivosidenib | n = 74 (Oligo = 39) | 8% | Elevated CK, QTc prolongation, diarrhea, transaminitis | 1% | Retrospective | Well tolerated |

| EORTC 26951 [15] | RT vs. RT + PCV | Phase III; n = 368 anaplastic oligodendroglial tumors (1p/19q-codeleted = 80) | Greater than or equal to 32% | Neutropenia, Thrombocytopenia, anemia, nausea, etc. | 52% PCV discontinued | Phase III RCT | Phase III RCT |

| RTOG 9402 [16] | RT vs. RT + PCV | n = 291 AO/AOA (known codeleted: 59) | 65% | Acute myelosuppression (neutropenia, thrombocytopenia), cognitive or mood change, peripheral/autonomic neuropathy, intractable vomiting, hepatic dysfunction, and severe allergic rash | 70% PCV discontinued | Phase III RCT | Phase III RCT |

| Rincon-Torroella et al., 2024 [24] | RT + PCV vs. RT + TMZ vs. RT | n = 277 oligodendroglioma | NR | Peripheral neuropathy, thrombocytopenia leukopenia, rash | 0% fully discontinued (PCV) | Retrospective cohort | Many modifications but no full discontinuations in PCV group. ~75% required PCV dose adjustment |

| Tabouret et al., 2015 [25] | PCV | n = 89 (Oligo = 64) | 46% | Anemia Thrombocytopenia Neutropenia | 61.8% | Retrospective | Toxicity-driven discontinuation negatively impacted survival (HR = 5.09) |

| Gonzalez-Aguilar et al., 2018 [19] | RT + PCV vs. RT + TMZ | n = 48 Oligo | PCV: 42.8% vs. TMZ: 11.1% | Leukopenia thrombocytopenia, etc. | PCV: 57.2%, TMZ: 19.8% | Retrospective | PCV group had higher hematologic toxicity, leading to lower completion rate |

| Ahn et al., 2022 [26] | PC vs. PCV | n = 59, Oligo = 9) | PCV: ≥70.4% vs. PC: ≥20% | Anemia, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, peripheral neuropathy (only in PCV group), etc. | PCV: 68.2% vs. PC: 26.7% | Single-institution retrospective | Lower toxicity with PC vs. PCV, but also potential efficacy differences |

| Study | Treatment | Population | Resistance Factor | Evidence Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mellinghoff et al., 2021 [11] | Vorasidenib | Phase I; n = 52 total (Oligo = 16) | Possible isoform switching or incomplete 2-HG suppression | Early-phase clinical data | PFS differed by tumor enhancement status |

| Mellinghoff et al., 2020 [12] | Ivosidenib | Phase I; n = 66 total (Oligo ≥ 3) | Co-mutations in cell-cycle genes shorten PFS in non-enhancing gliomas | Exploratory biomarker analysis | Non-enhancing tumors fared better |

| Natsume et al., 2022 [23] | DS-1001 | Phase I; n = 47 gliomas (15 Oligo) | Not clearly identified secondary mutation; drug retained 2-HG suppression | Phase I trial w/correlative data | Partial data on resistance |

| Spitzer et al., 2024 [27] | Ivosidenib/Vorasidenib | Preclinical and translational (n = 7 + in vivo) (3 oligos) | NOTCH1 mutation dampened differentiation response | Preclinical/translational | Astrocytic differentiation rescue overcame partial inhibitor resistance |

| EORTC 26951 [15] | RT vs. RT + PCV | Phase III; n = 368 anaplastic oligodendroglial tumors (1p/19q-codeleted = 80) | Oligodendrogliomas showed little OS/PFS gain→relative resistance to PCV | Phase III RCT | Benefit restricted to codeleted subset; PCV toxicity limited full 6-cycle completion |

| RTOG 9402 [16] | RT vs. RT + PCV | n = 291 AO/AOA (known codeleted: 59) | 1p/19q-intact oligodendrogliomas derived no OS benefit from PCV→RT (OS 2.6 y vs. 2.7 y) | Phase III RCT | Confirms codeletion as predictive; intact tumors relatively resistant |

| NOA-04 (Wick et al., 2016) [20] | PCV vs. TMZ vs. RT | n = 274 anaplastic gliomas (Oligo = 68) | Unmethylated MGMT promoter in IDH-wild-type/CIMP-negative tumors→limited benefit from alkylating chemotherapy | Phase III RCT w/subgroups | Better prognosis in IDH-mut/codel; resistance in IDH-wt/CIMP-neg |

| Van den Bent et al., 1998 [28] | PCV (Standard vs. Intensif.) | Recurrent Oligo/OA post-radiation (n = 52) | Early relapse (<1 yr after initial surgery ± RT)→low CR/PR rate (~25%) to PCV | Retrospective multicenter | Suggests chemo-resistance in early relapse |

| Study | Treatment | Identified Gap/Limitation |

|---|---|---|

| All IDH Inhibitor Trials | Vorasidenib, Ivosidenib, etc. | No direct PCV comparison; long-term OS data lacking; limited resistance data |

| RTOG 9402/EORTC 26951 [8] | RT + PCV | No IDH inhibitors studied; biomarker data limited; focused only on RT + PCV |

| Bell et al., 2020 [37] | RT ± PCV | Focused on high-risk LGG; post hoc IDH/codel analysis; side effect data limited |

| Lanman et al., 2024 [13] | Ivosidenib (retrospective) | Retrospective; possible selection bias; no OS data; inconsistent assessments |

| Tabouret et al., 2015 [25] | PCV (retrospective) | Multicenter; no comparison to TMZ/IDH inhibitors; retrospective toxicity reporting |

| Natsume et al., 2022 [23] | DS-1001 (phase I) | No biomarker analysis for resistance; small sample; early-phase design |

| NOA-04 (Wick et al., 2016) [20] | RT→chemo vs. chemo→RT (PCV/TMZ) | Randomization not specific to Oligo; subgroup lacked power |

| All PCV vs. TMZ Comparisons | PCV ± RT vs. TMZ ± RT | Retrospective; no RCTs in pure 1p/19q-codel, IDH-mut Oligos; toxicity underreported |

| Spitzer et al., 2024 [27] | Preclinical IDH inhibitors | Small tumor line sample |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duran, G.; Pichardo-Rojas, D.; Ali, A.H.; Passias, P.; Downes, A.; Ray, W.Z.; Zipfel, G.J.; Shakir, H.J.; Bauer, A.; Jea, A.; et al. Comparing Isocitrate Dehydrogenase Inhibitors with Procarbazine, Lomustine, and Vincristine Chemotherapy for Oligodendrogliomas. Cancers 2025, 17, 3880. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233880

Duran G, Pichardo-Rojas D, Ali AH, Passias P, Downes A, Ray WZ, Zipfel GJ, Shakir HJ, Bauer A, Jea A, et al. Comparing Isocitrate Dehydrogenase Inhibitors with Procarbazine, Lomustine, and Vincristine Chemotherapy for Oligodendrogliomas. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3880. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233880

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuran, Gerardo, Diego Pichardo-Rojas, Ahmed Hashim Ali, Peter Passias, Angela Downes, Wilson Z. Ray, Gregory J. Zipfel, Hakeem J. Shakir, Andrew Bauer, Andrew Jea, and et al. 2025. "Comparing Isocitrate Dehydrogenase Inhibitors with Procarbazine, Lomustine, and Vincristine Chemotherapy for Oligodendrogliomas" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3880. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233880

APA StyleDuran, G., Pichardo-Rojas, D., Ali, A. H., Passias, P., Downes, A., Ray, W. Z., Zipfel, G. J., Shakir, H. J., Bauer, A., Jea, A., Dunn, I. F., Zuccato, J. A., Graffeo, C. S., & Janjua, M. B. (2025). Comparing Isocitrate Dehydrogenase Inhibitors with Procarbazine, Lomustine, and Vincristine Chemotherapy for Oligodendrogliomas. Cancers, 17(23), 3880. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233880