The Prognostic Role of Different Blood Cell Count-to-Lymphocyte Ratios in Patients with Lung Cancer at Diagnosis

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Study Design and Patient Selection

2.2. Outcome Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

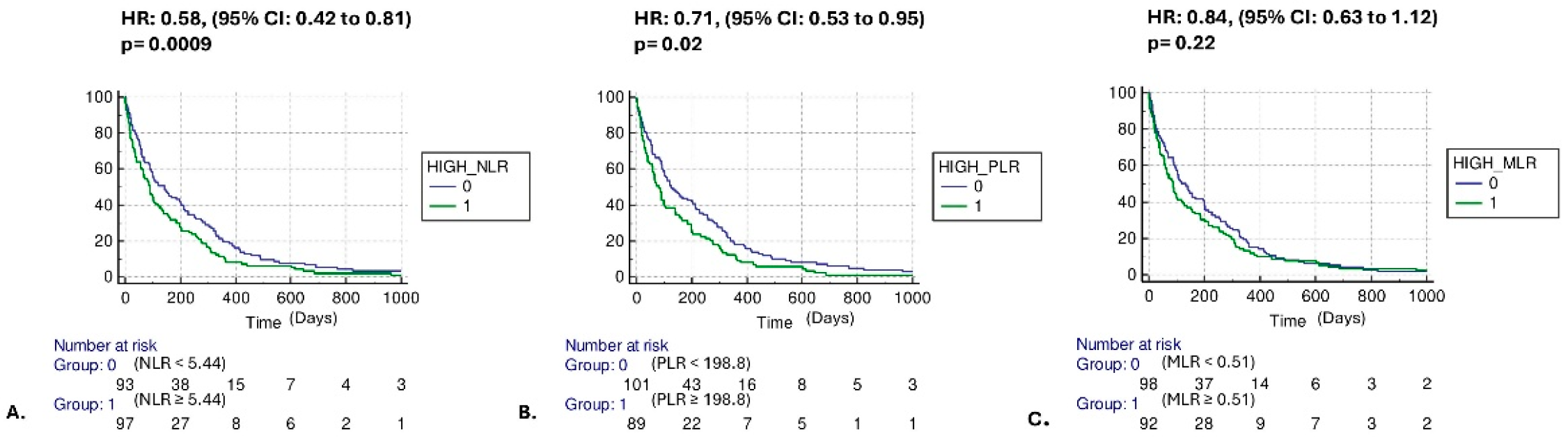

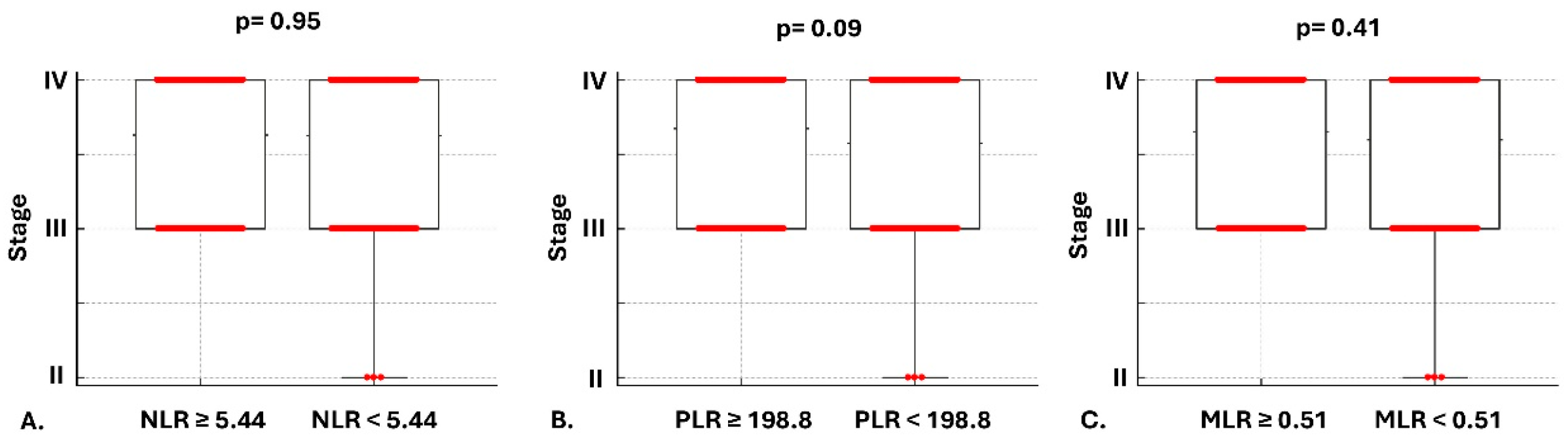

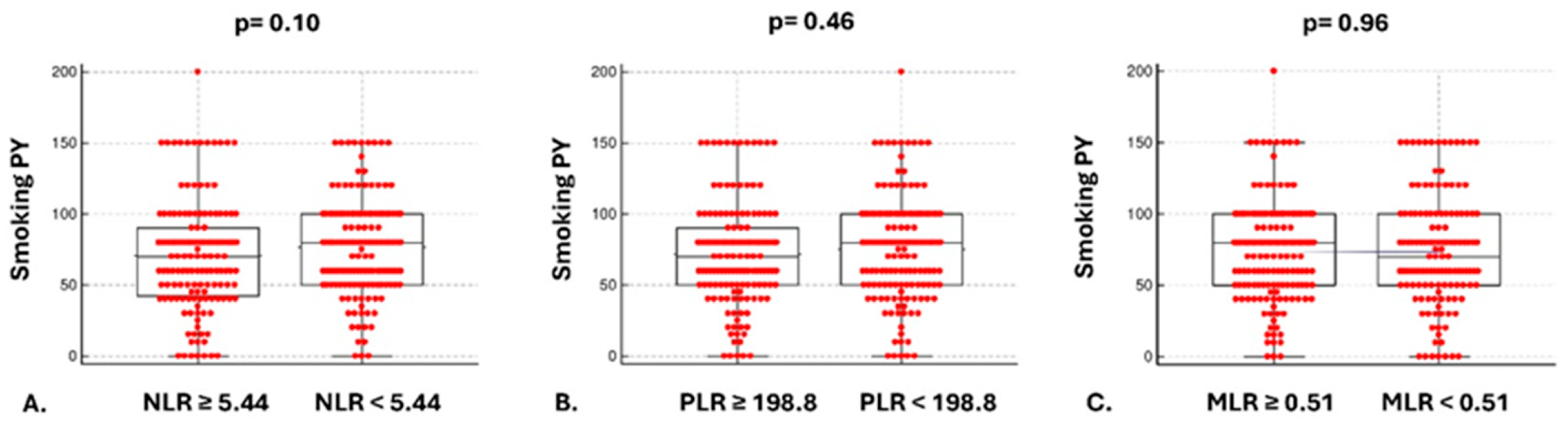

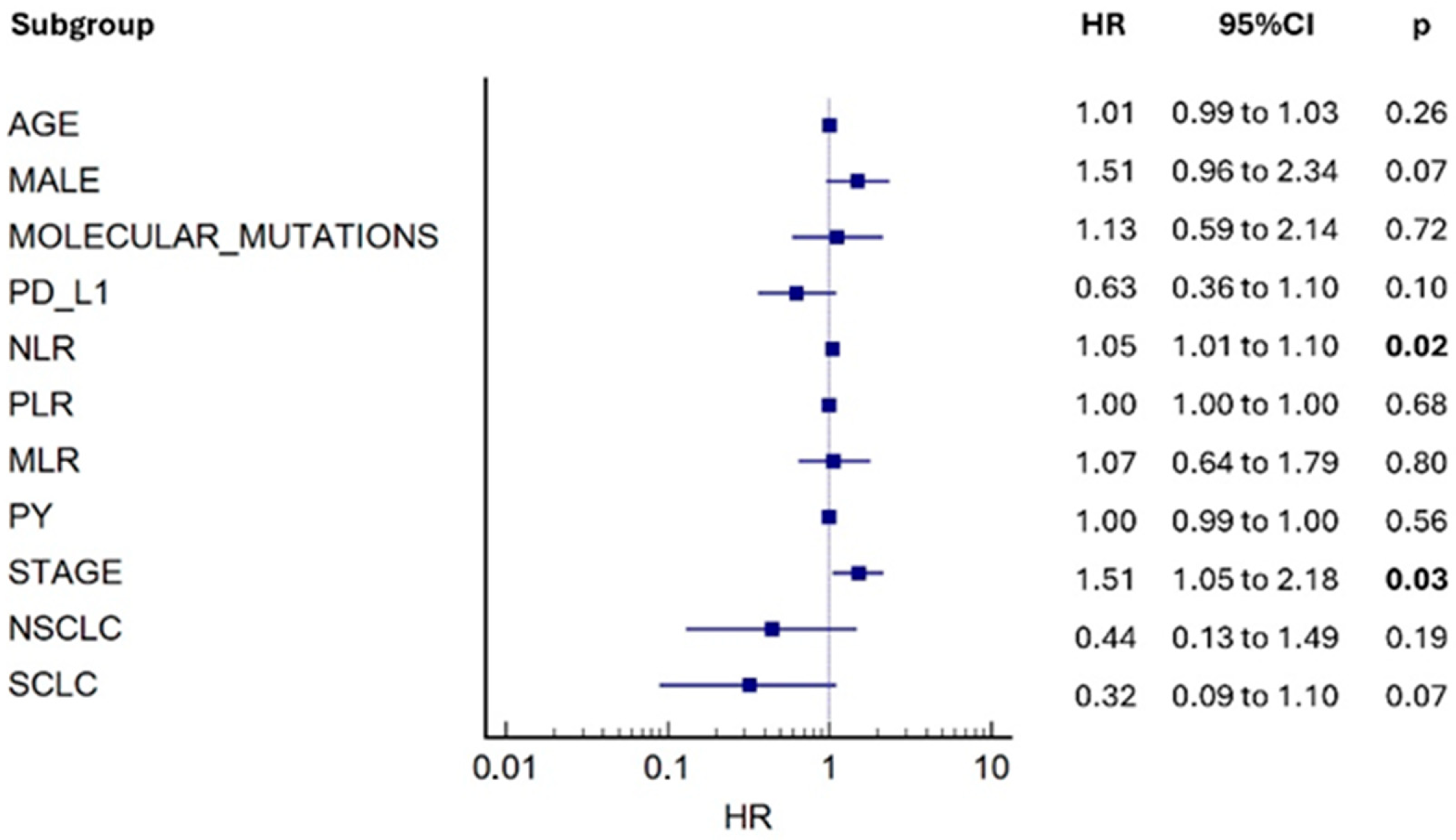

3.2. Mortality Risk and Secondary Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travis, W.D.; Brambilla, E.; Burke, A.P.; Marx, A.; Nicholson, A.G. Introduction to The 2015 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus, and Heart. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2015, 10, 1240–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlader, N.; Forjaz, G.; Mooradian, M.J.; Meza, R.; Kong, C.Y.; Cronin, K.A.; Mariotto, A.B.; Lowy, D.R.; Feuer, E.J. The Effect of Advances in Lung-Cancer Treatment on Population Mortality. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 640–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiste, O.; Gkiozos, I.; Charpidou, A.; Syrigos, N.K. Artificial Intelligence-Based Treatment Decisions: A New Era for NSCLC. Cancers 2024, 16, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampsonas, F.; Bosgana, P.; Psarros, E.; Papaioannou, O.; Tryfona, F.; Mantzouranis, K.; Katsaras, M.; Christopoulos, I.; Tsirikos, G.; Tsiri, P.; et al. Geographical Inequalities and Comorbidities in the Timely Diagnosis of NSCLC: A Real-Life Retrospective Study from a Tertiary Hospital in Western Greece. Cancers 2025, 17, 2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akcam, T.I.; Tekneci, A.K.; Turhan, K.; Duman, S.; Cuhatutar, S.; Ozkan, B.; Kaba, E.; Metin, M.; Cansever, L.; Sezen, C.B.; et al. Prognostic value of systemic inflammation markers in early stage non-small cell lung cancer. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 33886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grivennikov, S.I.; Greten, F.R.; Karin, M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 2010, 140, 883–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elinav, E.; Nowarski, R.; Thaiss, C.A.; Hu, B.; Jin, C.; Flavell, R.A. Inflammation-induced cancer: Crosstalk between tumours, immune cells and microorganisms. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2013, 13, 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tekneci, A.K.; Akcam, T.I.; Kavurmaci, O.; Ergonul, A.G.; Ozdil, A.; Turhan, K.; Çakan, A.; Çağırıcı, U. Relationship between survival and erythrocyte sedimentation rate in patients operated for lung cancer. Turk Gogus Kalp Damar Cerrahisi Derg. 2022, 30, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ethier, J.L.; Desautels, D.; Templeton, A.; Shah, P.S.; Amir, E. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res. 2017, 19, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.; Mu, X.; He, K.; Wang, P.; Wang, D.; Liu, C.; Yu, J. Prognostic value of lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio and systemic immune-inflammation index in non-small-cell lung cancer patients with brain metastases. Future Oncol. 2020, 16, 2433–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winther-Larsen, A.; Aggerholm-Pedersen, N.; Sandfeld-Paulsen, B. Inflammation scores as prognostic biomarkers in small cell lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.; Sun, H.; Lu, H.; Wu, J.; Wu, J.; Wu, Z.; Xi, J.; Liao, W.; Wang, Y. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio-based prognostic score can predict outcomes in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer treated with immunotherapy plus chemotherapy. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Liu, Y.; Qin, H.; Teng, Y.; Sun, R.; Ma, Z.; Wang, A.; Liu, J. Peripheral inflammatory factors as prognostic predictors for first-line PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M.K.D.; Quinn, K.; Li, Q.; Carroll, R.; Warsinske, H.; Vallania, F.; Chen, S.; Carns, M.A.; Aren, K.; Sun, J.; et al. Increased monocyte count as a cellular biomarker for poor outcomes in fibrotic diseases: A retrospective, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2019, 7, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, M.I.; Osadnik, C.R.; Bulfin, L.; Hamza, K.; Leong, P.; Wong, A.; King, P.T.; Bardin, P.G. Low and High Blood Eosinophil Counts as Biomarkers in Hospitalized Acute Exacerbations of COPD. Chest 2019, 156, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, L.M.; Beghe, B.; Papi, A. Blood eosinophils for the management of COPD patients? Lancet Respir. Med. 2018, 6, 807–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balkwill, F.; Mantovani, A. Inflammation and cancer: Back to Virchow? Lancet 2001, 357, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coussens, L.M.; Werb, Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature 2002, 420, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandaliya, H.; Jones, M.; Oldmeadow, C.; Nordman, I.I. Prognostic biomarkers in stage IV non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR), lymphocyte to monocyte ratio (LMR), platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and advanced lung cancer inflammation index (ALI). Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2019, 8, 886–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Ad, V.; Palmer, J.; Li, L.; Lai, Y.; Lu, B.; Myers, R.E.; Ye, Z.; Axelrod, R.; Johnson, J.M.; Werner-Wasik, M. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio associated with prognosis of lung cancer. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2017, 19, 711–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platini, H.; Ferdinand, E.; Kohar, K.; Prayogo, S.A.; Amirah, S.; Komariah, M.; Maulana, S. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio as Prognostic Markers for Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Treated with Immunotherapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicina 2022, 58, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco-Morales, M.; Soca-Chafre, G.; Barrios-Bernal, P.; Hernandez-Pedro, N.; Arrieta, O. Interplay between Cellular and Molecular Inflammatory Mediators in Lung Cancer. Mediat. Inflamm. 2016, 2016, 3494608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhou, B.P. Inflammation: A driving force speeds cancer metastasis. Cell Cycle 2009, 8, 3267–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condeelis, J.; Pollard, J.W. Macrophages: Obligate partners for tumor cell migration, invasion, and metastasis. Cell 2006, 124, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, J.W. Tumour-educated macrophages promote tumour progression and metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2004, 4, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, J.A.; Pollard, J.W. Microenvironmental regulation of metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahorec, R. Ratio of neutrophil to lymphocyte counts--rapid and simple parameter of systemic inflammation and stress in critically ill. Bratisl. Lekárske Listy 2001, 102, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, H.Y.; Chen, J.S.; Yeh, C.Y.; Changchien, C.R.; Tang, R.; Hsieh, P.S.; Tasi, W.-S.; You, J.-F.; You, Y.-T.; Fan, C.-W.; et al. Effect of preoperative neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio on the surgical outcomes of stage II colon cancer patients who do not receive adjuvant chemotherapy. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2011, 26, 1059–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Templeton, A.J.; McNamara, M.G.; Seruga, B.; Vera-Badillo, F.E.; Aneja, P.; Ocana, A.; Leibowitz-Amit, R.; Sonpavde, G.; Knox, J.J.; Tran, B.; et al. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014, 106, dju124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Yang, H.; Cai, D.; Xiang, L.; Fang, W.; Wang, R. Preoperative peripheral blood neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios (NLR) and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) related nomograms predict the survival of patients with limited-stage small-cell lung cancer. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2021, 10, 866–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.B.; Wang, Y.; Shan, B.J.; Lin, L.; Hao, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, W.; Pan, Y.Y. Prognostic Significance Of Platelet-To-Lymphocyte Ratio (PLR) And Mean Platelet Volume (MPV) During Etoposide-Based First-Line Treatment In Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 8965–8975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, R.; Wei, X.; Allen, P.K.; Cox, J.D.; Komaki, R.; Lin, S.H. Prognostic Significance of Total Lymphocyte Count, Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte Ratio, and Platelet-to-lymphocyte Ratio in Limited-stage Small-cell Lung Cancer. Clin. Lung Cancer 2019, 20, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Y.; Ye, S. Platelet-lymphocyte ratio is a prognostic marker in small cell lung cancer-A systemic review and meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1086742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Xiong, A.; Wang, S.; Xu, J.; Shen, Y.; Zhong, R.; Lu, J.; Chu, T.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y.; et al. Decreased monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio was associated with satisfied outcomes of first-line PD-1 inhibitors plus chemotherapy in stage IIIB-IV non-small cell lung cancer. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1094378. [Google Scholar]

- Ugel, S.; Cane, S.; De Sanctis, F.; Bronte, V. Monocytes in the Tumor Microenvironment. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2021, 16, 93–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grisaru-Tal, S.; Rothenberg, M.E.; Munitz, A. Eosinophil-lymphocyte interactions in the tumor microenvironment and cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Immunol. 2022, 23, 1309–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, S.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Ma, L.; Zhu, J.; Xin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, C.; Cheng, Y. Systemic immune-inflammation index, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio can predict clinical outcomes in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer treated with nivolumab. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2019, 33, e22964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, S.H.; Han, J.Y.; Kim, H.T.; Yun, T.; Lee, J.S. Early neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio reduction as a surrogate marker of prognosis in never smokers with advanced lung adenocarcinoma receiving gefitinib or standard chemotherapy as first-line therapy. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 138, 2009–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedres, S.; Torrejon, D.; Martinez, A.; Martinez, P.; Navarro, A.; Zamora, E.; Mulet-Margalef, N.; Felip, E. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) as an indicator of poor prognosis in stage IV non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2012, 14, 864–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarraf, K.M.; Belcher, E.; Raevsky, E.; Nicholson, A.G.; Goldstraw, P.; Lim, E. Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio and its association with survival after complete resection in non-small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2009, 137, 425–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teramukai, S.; Kitano, T.; Kishida, Y.; Kawahara, M.; Kubota, K.; Komuta, K.; Minato, K.; Mio, T.; Fujita, Y.; Yonei, T. Pretreatment neutrophil count as an independent prognostic factor in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: An analysis of Japan Multinational Trial Organisation LC00-03. Eur. J. Cancer 2009, 45, 1950–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomita, M.; Shimizu, T.; Ayabe, T.; Nakamura, K.; Onitsuka, T. Elevated preoperative inflammatory markers based on neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and C-reactive protein predict poor survival in resected non-small cell lung cancer. Anticancer Res. 2012, 32, 3535–3538. [Google Scholar]

- Jafri, S.H.; Shi, R.; Mills, G. Advance lung cancer inflammation index (ALI) at diagnosis is a prognostic marker in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): A retrospective review. BMC Cancer 2013, 13, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diem, S.; Schmid, S.; Krapf, M.; Flatz, L.; Born, D.; Jochum, W.; Templeton, A.J.; Früh, M. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte ratio (PLR) as prognostic markers in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with nivolumab. Lung Cancer 2017, 111, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinjab, A.; Rahal, Z.; Kadara, H. Cell-by-Cell: Unlocking Lung Cancer Pathogenesis. Cancers 2022, 14, 3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Zhao, Y.; Arkenau, H.T.; Lao, T.; Chu, L.; Xu, Q. Signal pathways and precision therapy of small-cell lung cancer. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Zheng, Z.; Liu, F.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Berardi, R.; Mohindra, P.; Zhu, Z.; Lin, J.; Chu, Q. A nomogram to predict the overall survival of patients with symptomatic extensive-stage small cell lung cancer treated with thoracic radiotherapy. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2021, 10, 2163–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.X.; Xiang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Chen, J. Assessment of systematic inflammatory and nutritional indexes in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer treated with first-line chemotherapy and atezolizumab. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2021, 70, 3199–3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Huang, Y.; Li, L.; Song, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, W. High neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios confer poor prognoses in patients with small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Shi, X.; Xiao, D.; He, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, W.; Zhao, Z.; Guo, Z.; Zou, X.; Zhang, J.; et al. Nomogram prediction for the survival of the patients with small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Dis. 2017, 9, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieshober, L.; Graw, S.; Barnett, M.J.; Goodman, G.E.; Chen, C.; Koestler, D.C.; Marsit, C.J.; Doherty, J.A. Pre-diagnosis neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and mortality in individuals who develop lung cancer. Cancer Causes Control 2021, 32, 1227–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tulgar, Y.K.; Cakar, S.; Tulgar, S.; Dalkilic, O.; Cakiroglu, B.; Uyanik, B.S. The effect of smoking on neutrophil/lymphocyte and platelet/lymphocyte ratio and platelet indices: A retrospective study. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2016, 20, 3112–3118. [Google Scholar]

- Gumus, F.; Solak, I.; Eryilmaz, M.A. The effects of smoking on neutrophil/lymphocyte, platelet//lymphocyte ratios. Bratisl. Lekárske Listy 2018, 119, 116–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, S.I.; Kim, R.B.; Song, H.N.; Kang, M.H.; Lee, U.S.; Choi, H.J.; Lee, S.J.; Cho, Y.J.; Jeong, Y.Y.; Kim, H.C.; et al. Prognostic significance of the lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio in patients with small cell lung cancer. Med. Oncol. 2014, 31, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, C.; Egger, F.; Alireza Hoda, M.; Saeed Querner, A.; Ferencz, B.; Lungu, V.; Szegedi, R.; Bogyo, L.; Torok, K.; Oberndorfer, F. Lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio is an independent prognostic factor in surgically treated small cell lung cancer: An international multicenter analysis. Lung Cancer 2022, 169, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A.; Allavena, P.; Sica, A.; Balkwill, F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature 2008, 454, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Visser, K.E.; Eichten, A.; Coussens, L.M. Paradoxical roles of the immune system during cancer development. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diakos, C.I.; Charles, K.A.; McMillan, D.C.; Clarke, S.J. Cancer-related inflammation and treatment effectiveness. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, e493–e503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nost, T.H.; Alcala, K.; Urbarova, I.; Byrne, K.S.; Guida, F.; Sandanger, T.M.; Johansson, M. Systemic inflammation markers and cancer incidence in the UK Biobank. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 36, 841–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sylman, J.L.; Mitrugno, A.; Atallah, M.; Tormoen, G.W.; Shatzel, J.J.; Tassi Yunga, S.; Wagner, T.H.; Leppert, J.T.; Mallick, P.; McCarty, O.J.T. The Predictive Value of Inflammation-Related Peripheral Blood Measurements in Cancer Staging and Prognosis. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolan, R.D.; McSorley, S.T.; Horgan, P.G.; Laird, B.; McMillan, D.C. The role of the systemic inflammatory response in predicting outcomes in patients with advanced inoperable cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2017, 116, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, B.; Yang, X.R.; Xu, Y.; Sun, Y.F.; Sun, C.; Guo, W.; Zhang, X.; Wang, W.M.; Qiu, S.J.; Zhou, J.; et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts prognosis of patients after curative resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 6212–6222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | (N, %) |

|---|---|

| Total number of patients | 353 |

| Age ± SD | 68.1 ± 9.1 |

| Male/Female | 275 (77.9%)/78 (22.1%) |

| Current smokers/Ex-smokers/ | 205 (58.1%)/138 (39.1%)/ |

| Never smokers | 10 (2.8%) |

| NSCLC/SCLC/NOS | 237 (67.1%)/105 (29.8%)/11 (3.1%) |

| adNSCLC/sqNSCLC | 142 (40.2%)/90 (25.5%) |

| EGFR/KRAS/ALK/BRAF mutations | 9 (2.5%)/31 (8.8%)/3 (0.8%)/3 (0.8%) |

| PD-L1 expression TPS: <1%/1–49%/≥50% | 47 (13.3%)/32 (9.1%)/41 (11.6%) |

| Stage IIA/IIB/IIIA/IIIB/IIIC/IVA/IVB | 1 (0.3%)/2 (0.6%)/31 (8.7%)/94 (26.6%)/2 (0.6%)/80 (22.7%)/143 (40.5%) |

| NLR (%95CI) | PLR (95%CI) | MLR (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NSCLC | 5.84 (5.16 to 6.48) | 205.5 (189.4 to 244.1) | 0.52 (0.48 to 0.57) |

| SCLC | 5.05 (4.40 to 5.56) | 182.3 (157.5 to 213.2) | 0.49 (0.42 to 0.53) |

| adNSCLC | 5.80 (4.85 to 6.54) | 207.8 (176.6 to 244.8) | 0.53 (0.47 to 0.58) |

| sqNSCLC | 5.69 (4.96 to 6.66) | 201.7 (184.4 to 252.2) | 0.52 (0.48 to 0.61) |

| Stage IIIA/IIIB/IIIC | 5.56 (4.88 to 6.21) | 187.2 (174.9 to 235.5) | 0.50 (0.46 to 0.57) |

| Stage IVA/IVB | 5.30 (4.98 to 6.14) | 205.5 (188.6 to 229.2) | 0.51 (0.48 to 0.56) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Papaioannou, O.; Fiste, O.; Theohari, E.; Sampsonas, F.; Dimitrakopoulos, F.-I.; Koutras, A.; Gkiozos, I.; Vathiotis, I.; Kotteas, E.; Tzouvelekis, A. The Prognostic Role of Different Blood Cell Count-to-Lymphocyte Ratios in Patients with Lung Cancer at Diagnosis. Cancers 2025, 17, 3879. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233879

Papaioannou O, Fiste O, Theohari E, Sampsonas F, Dimitrakopoulos F-I, Koutras A, Gkiozos I, Vathiotis I, Kotteas E, Tzouvelekis A. The Prognostic Role of Different Blood Cell Count-to-Lymphocyte Ratios in Patients with Lung Cancer at Diagnosis. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3879. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233879

Chicago/Turabian StylePapaioannou, Ourania, Oraianthi Fiste, Eva Theohari, Fotios Sampsonas, Foteinos-Ioannis Dimitrakopoulos, Angelos Koutras, Ioannis Gkiozos, Ioannis Vathiotis, Elias Kotteas, and Argyrios Tzouvelekis. 2025. "The Prognostic Role of Different Blood Cell Count-to-Lymphocyte Ratios in Patients with Lung Cancer at Diagnosis" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3879. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233879

APA StylePapaioannou, O., Fiste, O., Theohari, E., Sampsonas, F., Dimitrakopoulos, F.-I., Koutras, A., Gkiozos, I., Vathiotis, I., Kotteas, E., & Tzouvelekis, A. (2025). The Prognostic Role of Different Blood Cell Count-to-Lymphocyte Ratios in Patients with Lung Cancer at Diagnosis. Cancers, 17(23), 3879. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233879