CRISPR-Cas9 Genome and Double-Knockout Screening to Identify Novel Therapeutic Targets for Chemoresistance in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Triple Negative Breast Cancer Transcriptome Data Collection

2.2. Bioinformatics Data Analyses of Transcriptome Between TNBC Cell Lines and Tumor Samples

2.2.1. Pre-Processing of Data for Gene Expression Profiles

2.2.2. Bach Effect Removal

2.2.3. Different Gene Expression and Hierarchical Cluster Analysis

2.2.4. Correlation Analysis Between TNBC Cell Lines and TNBC Patient Samples Who Were Poor Responders to Chemotherapy

2.2.5. ssGSEA Pathway Similarity Analysis

2.2.6. Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG Pathway Analysis

2.3. Cell Culture

2.3.1. Cell Survival Assay Using siRNA-Mediated Gene Silencing

2.3.2. Cell Survival Assay Using Single Drug

2.3.3. Cell Survival Assay Using Drug Combination

2.4. Genome-Wide CRISPR-Cas9 Screening of Chemoresistance and Data Analysis

2.4.1. Construction of TKOv3 Library

2.4.2. Genome-Wide Pooled sgRNA Screens

2.4.3. Analysis of CRISPR Screening Data

2.5. Bulk RNA Sequencing

2.6. CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Combination Double-Knockout Screening

2.6.1. Selection of Candidate Genes

2.6.2. Library Construction

2.6.3. Pooled sgRNA Screening

2.6.4. CDKO CRISPR Sequencing Data Analysis

3. Results

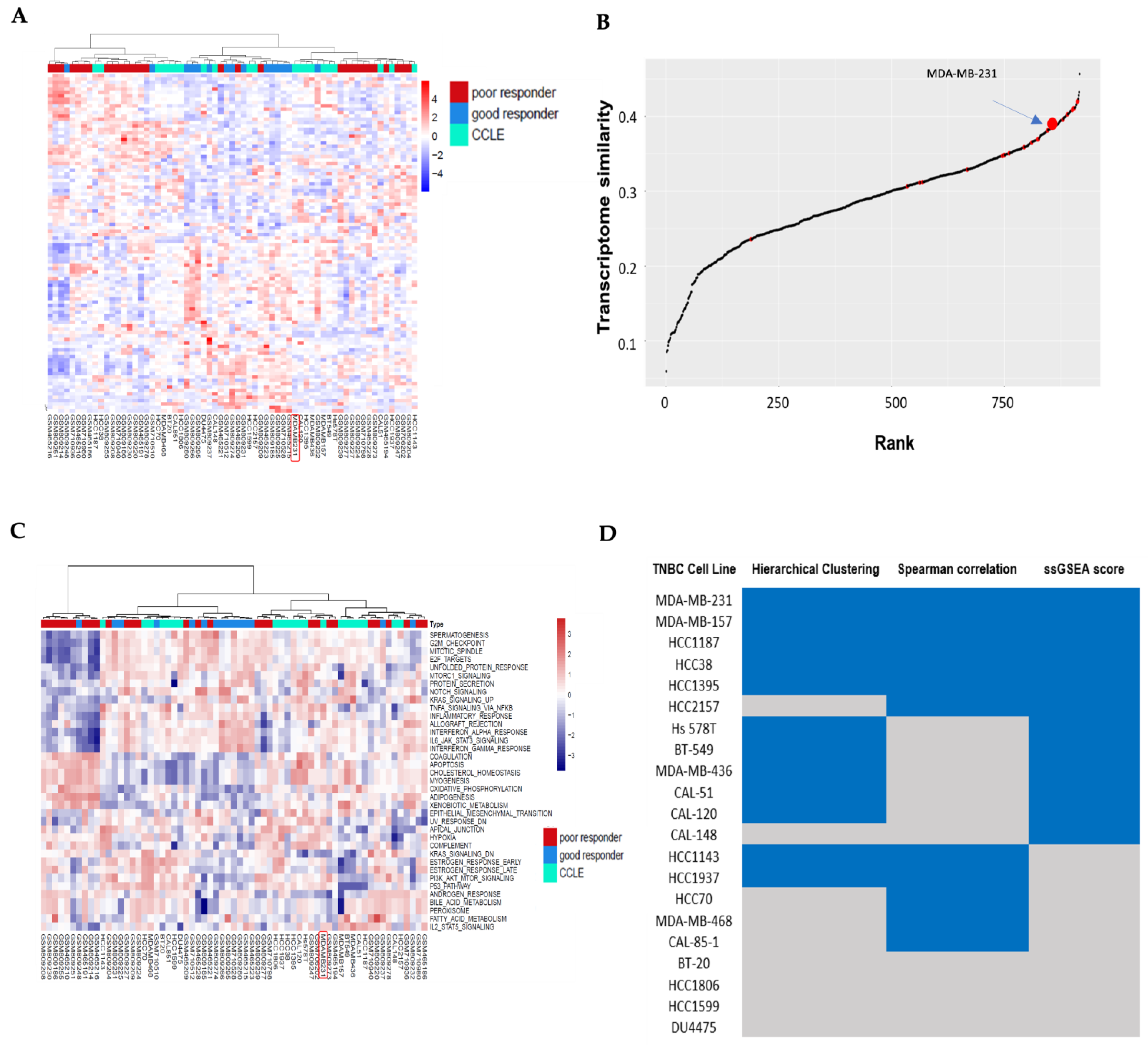

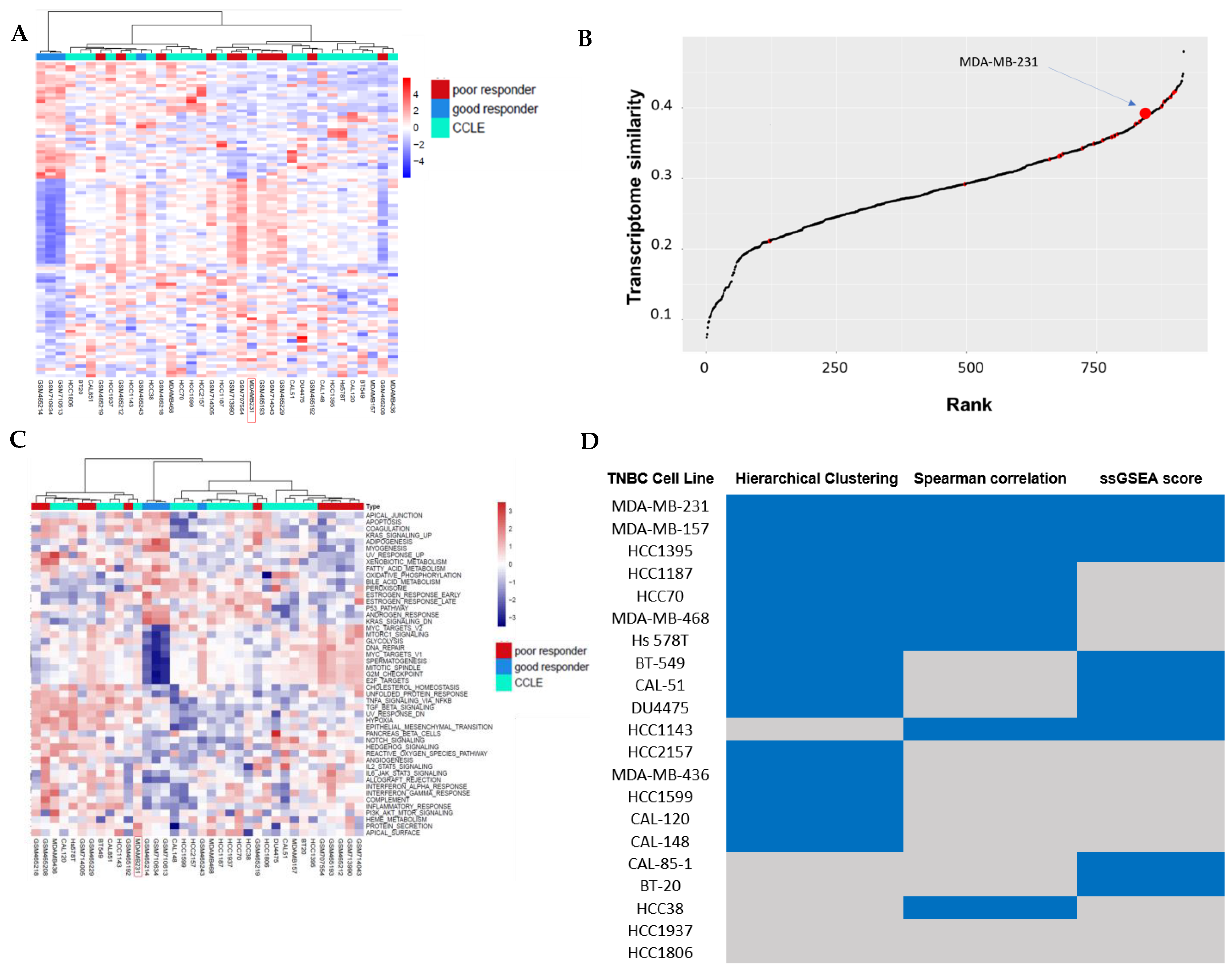

3.1. Hierarchical Clustering Analysis of TNBC Transcriptome Profiles Between Patients and Cell Lines

3.2. Correlation Analysis Between TNBC Cell Lines and TNBC Non-Responders of Chemotherapy

3.3. Pathway Similarity Analysis by Single-Sample Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (ssGSEA) Score and Overall Similarity Analysis Between TNBC Cell Lines and TNBC Chemotherapy Non-Responders

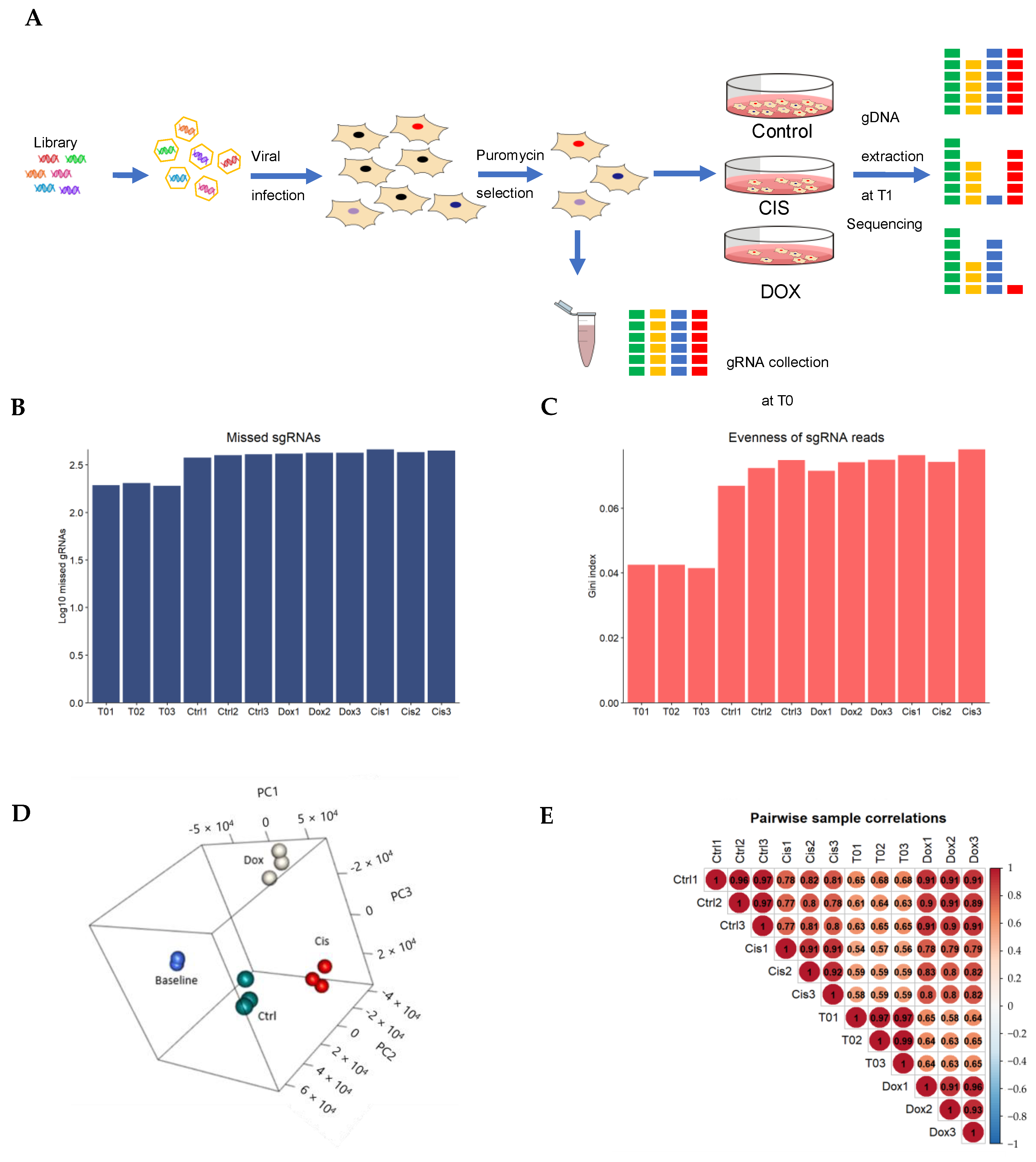

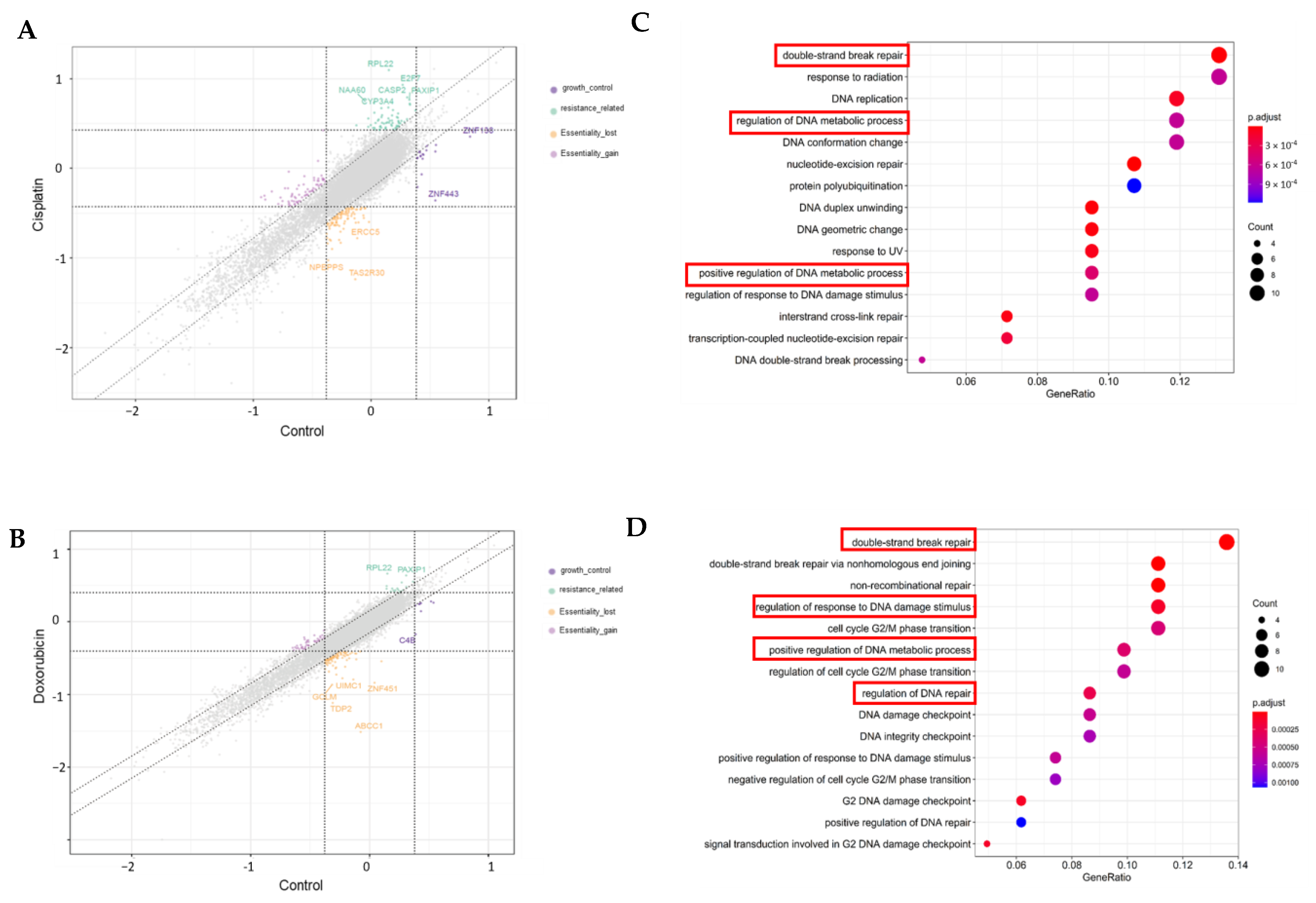

3.4. Genome-Wide CRISPR Screening on MDA-MB-231 Cell Lines

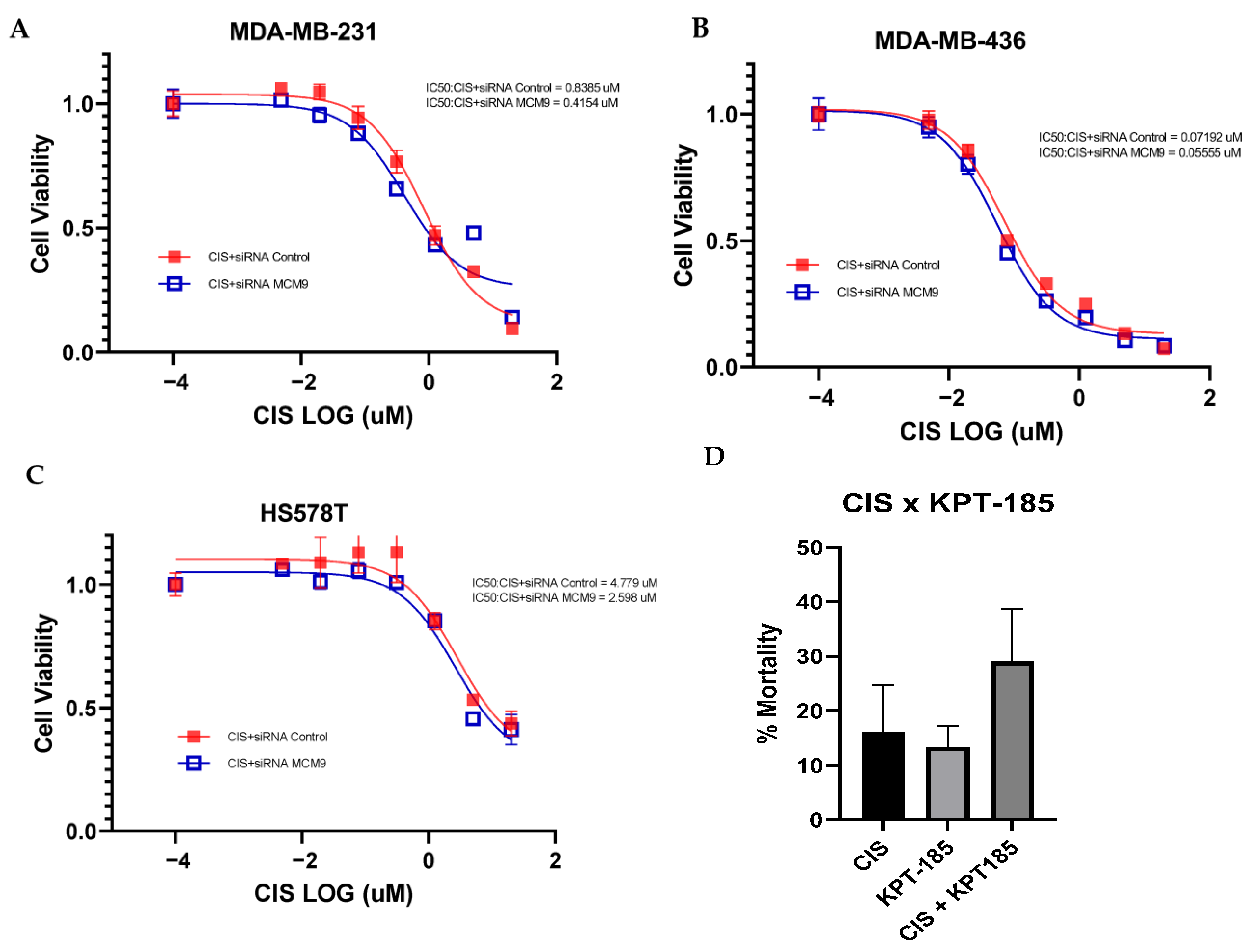

3.5. Validation of Targeted Gene Knockout for Increased Chemo-Sensitivity in TNBC

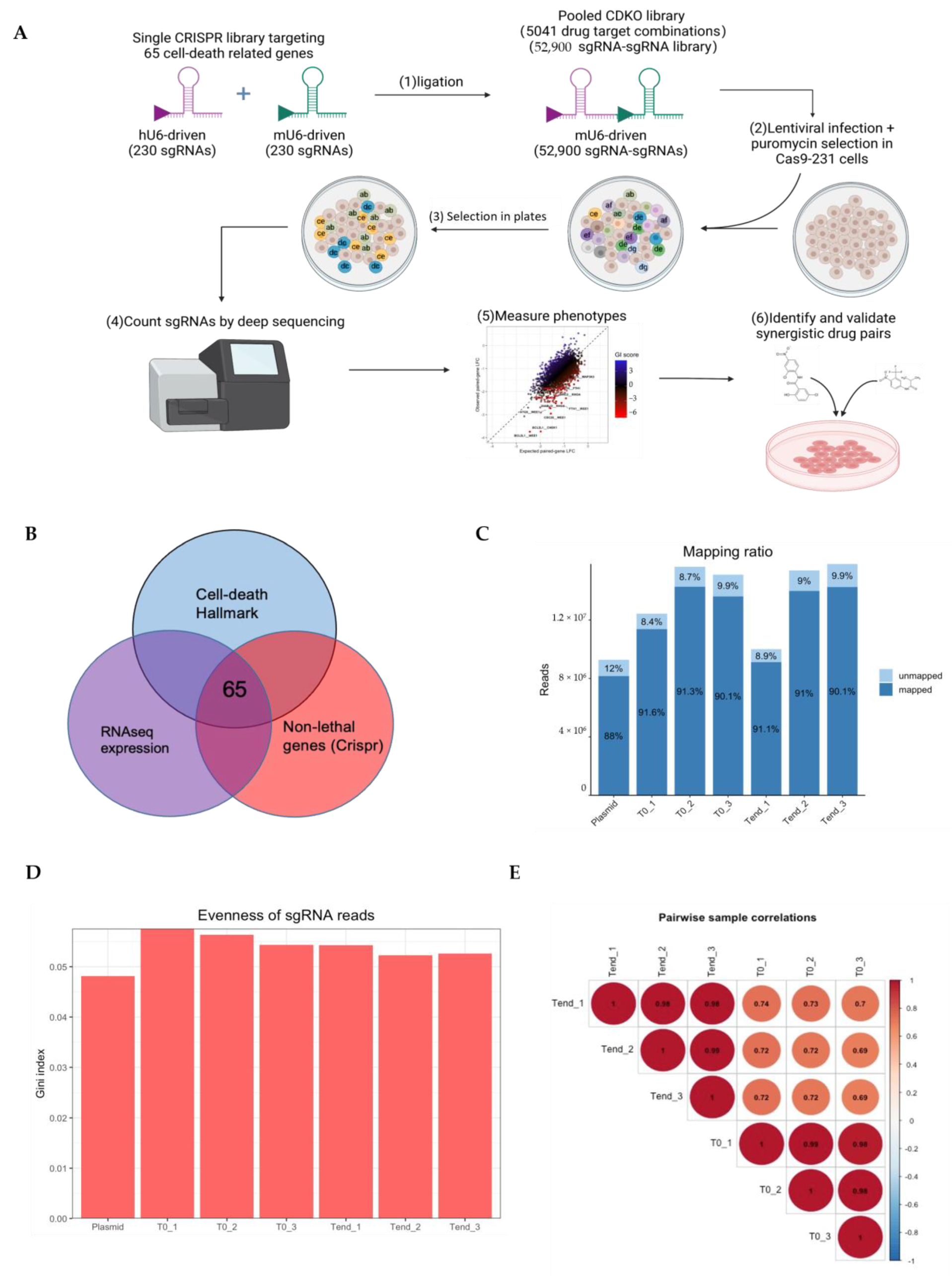

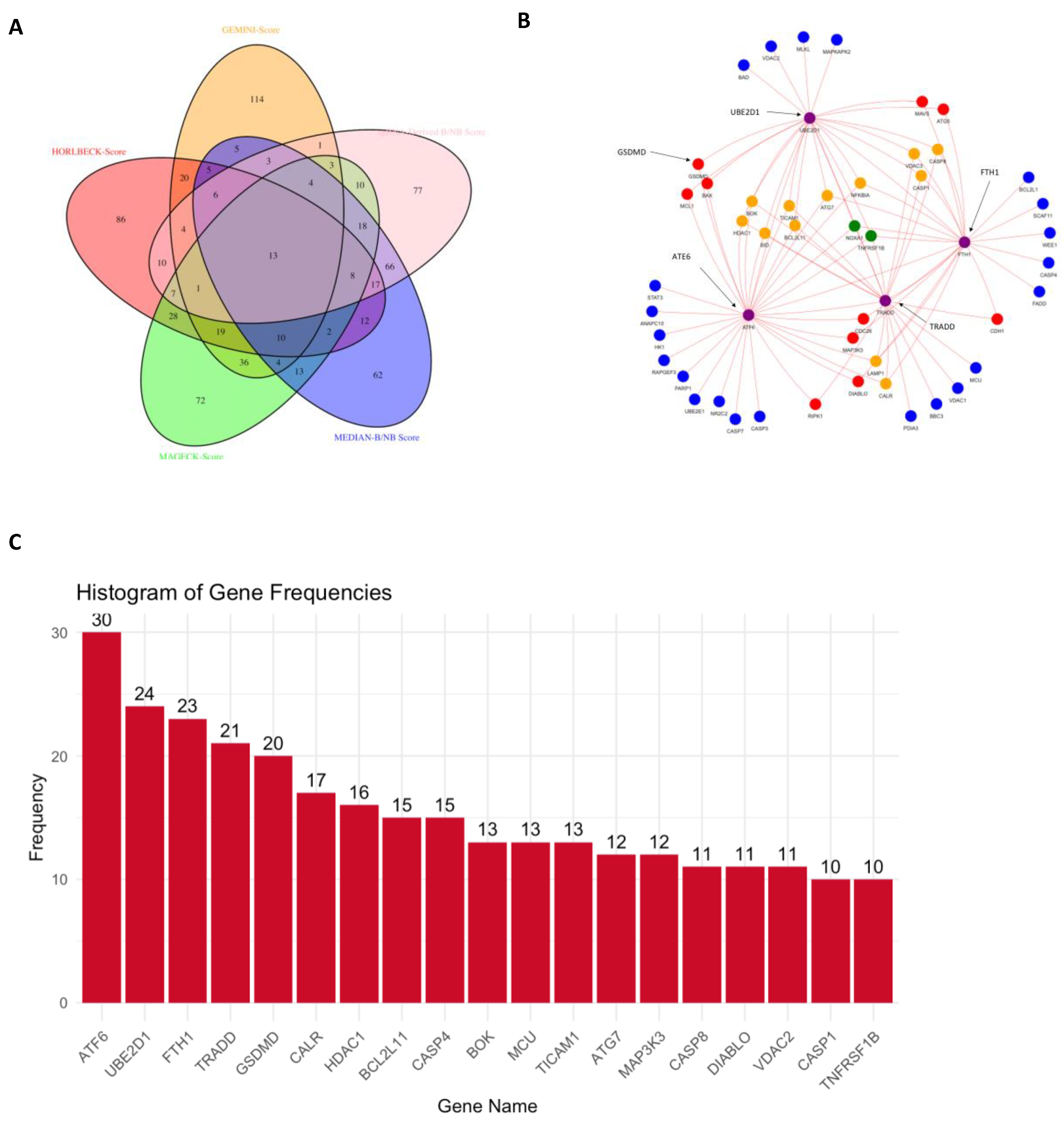

3.6. CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Combination Double-Knockout (CDKO) Experiment

4. Discussion

4.1. CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Combination Double-Knockout (CDKO) Experiment

4.2. TNBC Chemo-Resistant Target Discovery Through Genome-Wide CRISPR-Cas9 Screening and Validation Analyses

4.3. Discovery of Synthetic Lethal Gene Pairs in TNBC Cells

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADCs | Antibodydrug conjugates |

| AML | Acute myeloid leukemia |

| B/NB | Score with and without background normalization |

| CDKO | Combination double-knockout |

| EMT | Epithelialmesenchymal transition |

| ER | Estrogen receptor |

| GEO | Gene Expression Omnibus |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| GSVA | Gene set variation analysis |

| hGECKOv2 | Human genome CRISPR knockout version 2 |

| HDAC | Histone deacetylase |

| HER2 | Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 |

| HMAs | Hypomethylating agents |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| KinomeKO | Human kinome CRISPR knockout |

| MOI | Multiplicity of infection |

| MP | MillerPayne |

| MSigDB | Molecular Signatures Database |

| mTOR | Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| NACT | Neoadjuvant chemotherapy |

| NER | Nucleotide excision repair |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| PARP | Poly(ADPribose) polymerase |

| PARPis | Poly(ADPribose) polymerase inhibitors |

| PCRs | Polymerase chain reactions |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3kinase |

| PR | Progesterone receptor |

| RMA | Robust multiarray average |

| RRA | Robust rank aggregation |

| SL | Synthetic lethality |

| SLKB | Synthetic Lethality Knowledgebase |

| ssGSEA | Singlesample Gene Set Enrichment Analysis |

| STR | Short tandem repeat |

| TKOv3 | Toronto Knockout CRISPR library version 3 |

| VBC | Vienna Bioactivity CRISPR |

References

- Ades, F.; Zardavas, D.; Bozovic-Spasojevic, I.; Pugliano, L.; Fumagalli, D.; De Azambuja, E.; Viale, G.; Sotiriou, C.; Piccart, M. Luminal B breast cancer: Molecular characterization, clinical management, and future perspectives. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 2794–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedeljković, M.; Damjanović, A. Mechanisms of chemotherapy resistance in triple-negative breast cancer—How we can rise to the challenge. Cells 2019, 8, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yagata, H.; Kajiura, Y.; Yamauchi, H. Current strategy for triple-negative breast cancer: Appropriate combination of surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. Breast Cancer 2011, 18, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasari, S.; Tchounwou, P.B. Cisplatin in cancer therapy: Molecular mechanisms of action. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 740, 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivankar, S. An overview of doxorubicin formulations in cancer therapy. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2014, 10, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keam, B.; Im, S.-A.; Kim, H.-J.; Oh, D.-Y.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, S.-H.; Chie, E.K.; Han, W.; Kim, D.-W.; Moon, W.K. Prognostic impact of clinicopathologic parameters in stage II/III breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant docetaxel and doxorubicin chemotherapy: Paradoxical features of the triple negative breast cancer. BMC Cancer 2007, 7, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrski, T.; Huzarski, T.; Dent, R.; Gronwald, J.; Zuziak, D.; Cybulski, C.; Kladny, J.; Gorski, B.; Lubinski, J.; Narod, S. Response to neoadjuvant therapy with cisplatin in BRCA1-positive breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2009, 115, 359–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikov, W.M.; Berry, D.A.; Perou, C.M.; Singh, B.; Cirrincione, C.T.; Tolaney, S.M.; Kuzma, C.S.; Pluard, T.J.; Somlo, G.; Port, E.R. Impact of the addition of carboplatin and/or bevacizumab to neoadjuvant once-per-week paclitaxel followed by dose-dense doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide on pathologic complete response rates in stage II to III triple-negative breast cancer: CALGB 40603 (Alliance). J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Loibl, S.; O’Shaughnessy, J.; Untch, M.; Sikov, W.M.; Rugo, H.S.; McKee, M.D.; Huober, J.; Golshan, M.; von Minckwitz, G.; Maag, D. Addition of the PARP inhibitor veliparib plus carboplatin or carboplatin alone to standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer (BrighTNess): A randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, P.; Cortes, J.; Pusztai, L.; McArthur, H.; Kümmel, S.; Bergh, J.; Denkert, C.; Park, Y.H.; Hui, R.; Harbeck, N. Pembrolizumab for early triple-negative breast cancer. New Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 810–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, P.; Adams, S.; Rugo, H.S.; Schneeweiss, A.; Barrios, C.H.; Iwata, H.; Diéras, V.; Hegg, R.; Im, S.-A.; Shaw Wright, G. Atezolizumab and nab-paclitaxel in advanced triple-negative breast cancer. New Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2108–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, R.A.; Lindeman, G.J.; Clemons, M.; Wildiers, H.; Chan, A.; McCarthy, N.J.; Singer, C.F.; Lowe, E.S.; Watkins, C.L.; Carmichael, J. Phase I trial of the oral PARP inhibitor olaparib in combination with paclitaxel for first-or second-line treatment of patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2013, 15, R88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geenen, J.J.; Linn, S.C.; Beijnen, J.H.; Schellens, J.H. PARP inhibitors in the treatment of triple-negative breast cancer. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2018, 57, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagayama, A.; Vidula, N.; Ellisen, L.; Bardia, A. Novel antibody–drug conjugates for triple negative breast cancer. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2020, 12, 1758835920915980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Tsai, M.-H.; Lu, J.; Yu, T.; Jin, J.; Xiao, D.; Jiang, H.; Han, M.; Wang, M.; Wang, J. Site-specific and hydrophilic ADCs through disulfide-bridged linker and branched PEG. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 28, 1363–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, T.G. Targeted therapies for triple-negative breast cancer. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2019, 20, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradbury, A.; Hall, S.; Curtin, N.; Drew, Y. Targeting ATR as Cancer Therapy: A new era for synthetic lethality and synergistic combinations? Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 207, 107450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, C.; Castroviejo-Bermejo, M.; Gutiérrez-Enríquez, S.; Llop-Guevara, A.; Ibrahim, Y.; Gris-Oliver, A.; Bonache, S.; Morancho, B.; Bruna, A.; Rueda, O. RAD51 foci as a functional biomarker of homologous recombination repair and PARP inhibitor resistance in germline BRCA-mutated breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 1203–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortesi, L.; Rugo, H.S.; Jackisch, C. An overview of PARP inhibitors for the treatment of breast cancer. Target. Oncol. 2021, 16, 255–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, F.A.; Hsu, P.D.; Wright, J.; Agarwala, V.; Scott, D.A.; Zhang, F. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat. Protoc. 2013, 8, 2281–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjana, N.E.; Shalem, O.; Zhang, F. Improved vectors and genome-wide libraries for CRISPR screening. Nat. Methods 2014, 11, 783–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.; Yan, G.; Wang, N.; Daliah, G.; Edick, A.M.; Poulet, S.; Boudreault, J.; Ali, S.; Burgos, S.A.; Lebrun, J.-J. In vivo genome-wide CRISPR screen reveals breast cancer vulnerabilities and synergistic mTOR/Hippo targeted combination therapy. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadepalli, V.S.; Kim, H.; Liu, Y.; Han, T.; Cheng, L. XDeathDB: A visualization platform for cell death molecular interactions. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Gökbağ, B.; Fan, K.; Shao, S.; Huo, Y.; Wu, X.; Cheng, L.; Li, L. Synthetic lethal gene pairs: Experimental approaches and predictive models. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 961611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillet, J.-P.; Varma, S.; Gottesman, M.M. The Clinical Relevance of Cancer Cell Lines. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2013, 105, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilding, J.L.; Bodmer, W.F. Cancer Cell Lines for Drug Discovery and DevelopmentCancer Cell Lines for Drug Discovery and Development. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 2377–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Newbury, P.A.; Glicksberg, B.S.; Zeng, W.Z.; Paithankar, S.; Andrechek, E.R.; Chen, B. Evaluating cell lines as models for metastatic breast cancer through integrative analysis of genomic data. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domcke, S.; Sinha, R.; Levine, D.A.; Sander, C.; Schultz, N. Evaluating cell lines as tumour models by comparison of genomic profiles. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Y.; Shao, S.; Liu, E.; Li, J.; Tian, Z.; Wu, X.; Zhang, S.; Stover, D.; Wu, H.; Cheng, L.; et al. Subpathway Analysis of Transcriptome Profiles Reveals New Molecular Mechanisms of Acquired Chemotherapy Resistance in Breast Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 4878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barretina, J.; Caponigro, G.; Stransky, N.; Venkatesan, K.; Margolin, A.A.; Kim, S.; Wilson, C.J.; Lehár, J.; Kryukov, G.V.; Sonkin, D.; et al. The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature 2012, 483, 603–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Ramirez, L.; Sanchez-Rovira, P.; Ramirez-Tortosa, C.L.; Quiles, J.L.; Ramirez-Tortosa, M.; Lorente, J.A. Transcriptional Shift Identifies a Set of Genes Driving Breast Cancer Chemoresistance. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korde, L.A.; Lusa, L.; McShane, L.; Lebowitz, P.F.; Lukes, L.; Camphausen, K.; Parker, J.S.; Swain, S.M.; Hunter, K.; Zujewski, J.A. Gene expression pathway analysis to predict response to neoadjuvant docetaxel and capecitabine for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2010, 119, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, T.; Nakayama, T.; Naoi, Y.; Yamamoto, N.; Otani, Y.; Kim, S.J.; Shimazu, K.; Shimomura, A.; Maruyama, N.; Tamaki, Y.; et al. GSTP1 expression predicts poor pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in ER-negative breast cancer. Cancer Sci. 2012, 103, 913–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team R.C. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, M.E.; Phipson, B.; Wu, D.; Hu, Y.; Law, C.W.; Shi, W.; Smyth, G.K. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hänzelmann, S.; Castelo, R.; Guinney, J. GSVA: Gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-Seq data. BMC Bioinform. 2013, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberzon, A.; Birger, C.; Thorvaldsdóttir, H.; Ghandi, M.; Mesirov, J.P.; Tamayo, P. The Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) Hallmark Gene Set Collection. Cell Syst. 2015, 1, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashburner, M.; Ball, C.A.; Blake, J.A.; Botstein, D.; Butler, H.; Cherry, J.M.; Davis, A.P.; Dolinski, K.; Dwight, S.S.; Eppig, J.T.; et al. Gene ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet. 2000, 25, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.-G.; Han, Y.; He, Q.-Y. clusterProfiler: An R Package for Comparing Biological Themes Among Gene Clusters. OMICS J. Integr. Biol. 2012, 16, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, T.; Tong, A.H.Y.; Chan, K.; Van Leeuwen, J.; Seetharaman, A.; Aregger, M.; Chandrashekhar, M.; Hustedt, N.; Seth, S.; Noonan, A.; et al. Evaluation and Design of Genome-Wide CRISPR/SpCas9 Knockout Screens. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genet. 2017, 7, 2719–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xu, H.; Xiao, T.; Cong, L.; Love, M.I.; Zhang, F.; Irizarry, R.A.; Liu, J.S.; Brown, M.; Liu, X.S. MAGeCK enables robust identification of essential genes from genome-scale CRISPR/Cas9 knockout screens. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Köster, J.; Xu, H.; Chen, C.-H.; Xiao, T.; Liu, J.S.; Brown, M.; Liu, X.S. Quality control, modeling, and visualization of CRISPR screens with MAGeCK-VISPR. Genome Biol. 2015, 16, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringnér, M. What is principal component analysis? Nat. Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 303–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.; Wu, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Shao, S.; Gokbag, B.; Fan, K.; Liu, X.; Li, F.; et al. Generation of dual-gRNA library for combinatorial CRISPR screening of synthetic lethal gene pairs. STAR Protoc. 2022, 3, 101556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, B.; Tomic, J.; Masud, S.N.; Tonge, P.; Weiss, A.; Usaj, M.; Tong, A.H.Y.; Kwan, J.J.; Brown, K.R.; Titus, E.; et al. Essential Gene Profiles for Human Pluripotent Stem Cells Identify Uncharacterized Genes and Substrate Dependencies. Cell Rep. 2019, 27, 599–615.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michlits, G.; Jude, J.; Hinterndorfer, M.; de Almeida, M.; Vainorius, G.; Hubmann, M.; Neumann, T.; Schleiffer, A.; Burkard, T.R.; Fellner, M.; et al. Multilayered VBC score predicts sgRNAs that efficiently generate loss-of-function alleles. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 708–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Wu, D.; Fang, Y.; Wu, M.; Cai, R.; Li, X. Prediction of Synthetic Lethal Interactions in Human Cancers using Multi-view Graph Auto-Encoder. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2021, 25, 4041–4051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horlbeck, M.A.; Xu, A.; Wang, M.; Bennett, N.K.; Park, C.Y.; Bogdanoff, D.; Adamson, B.; Chow, E.D.; Kampmann, M.; Peterson, T.R.; et al. Mapping the Genetic Landscape of Human Cells. Cell 2018, 174, 953–967.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kweon, J.; Kim, D.-E.; Jang, A.-H.; Kim, Y. CRISPR/Cas-based customization of pooled CRISPR libraries. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökbağ, B.; Tang, S.; Fan, K.; Cheng, L.; Yu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Li, L. SLKB: Synthetic lethality knowledge base. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 52, D1418–D1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westhoff, G.L.; Chen, Y.; Teng, N.N.H. Targeting FOXM1 Improves Cytotoxicity of Paclitaxel and Cisplatinum in Platinum-Resistant Ovarian Cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2017, 27, 1602–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Liao, C.; Hu, X.; Fan, L.; Kang, Q.; Zeng, Y.; Wu, X.; et al. Inhibition of autophagosome-lysosome fusion by ginsenoside Ro via the ESR2-NCF1-ROS pathway sensitizes esophageal cancer cells to 5-fluorouracil-induced cell death via the CHEK1-mediated DNA damage checkpoint. Autophagy 2016, 12, 1593–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosinsky, R.L.; Helms, M.; Zerche, M.; Wohn, L.; Dyas, A.; Prokakis, E.; Kazerouni, Z.B.; Bedi, U.; Wegwitz, F.; Johnsen, S.A. USP22-dependent HSP90AB1 expression promotes resistance to HSP90 inhibition in mammary and colorectal cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Qin, B.; Moyer, A.M.; Nowsheen, S.; Liu, T.; Qin, S.; Zhuang, Y.; Liu, D.; Lu, S.W.; Kalari, K.R.; et al. DNA methyltransferase expression in triple-negative breast cancer predicts sensitivity to decitabine. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 2376–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, J.-Y.; Hsu, J.L.; Meric-Bernstam, F.; Chang, C.-J.; Wang, Q.; Bao, Y.; Yamaguchi, H.; Xie, X.; Woodward, W.A.; Yu, D.; et al. BikDD Eliminates Breast Cancer Initiating Cells and Synergizes with Lapatinib for Breast Cancer Treatment. Cancer Cell 2011, 20, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano-Oviedo, L.; Nuncia-Cantarero, M.; Morcillo-Garcia, S.; Nieto-Jimenez, C.; Burgos, M.; Corrales-Sanchez, V.; Perez-Peña, J.; Győrffy, B.; Ocaña, A.; Galán-Moya, E.M. Identification of a stemness-related gene panel associated with BET inhibition in triple negative breast cancer. Cell. Oncol. 2020, 43, 431–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Chang, J.T.; Geradts, J.; Neckers, L.M.; Haystead, T.; Spector, N.L.; Lyerly, H.K. Amplification and high-level expression of heat shock protein 90 marks aggressive phenotypes of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2012, 14, R62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; He, Y.; Lu, L.-L.; Zhou, Z.-Y.; Wan, N.-B.; Li, G.-P.; He, X.; Deng, H.-W. miRNA-192-5p impacts the sensitivity of breast cancer cells to doxorubicin via targeting peptidylprolyl isomerase A. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2019, 35, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Qiu, N.; Yin, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Guo, W.; Liu, M.; Liu, T.; Chen, D.; Luo, K.; et al. SRGN crosstalks with YAP to maintain chemoresistance and stemness in breast cancer cells by modulating HDAC2 expression. Theranostics 2020, 10, 4290–4307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herok, M.; Wawrzynow, B.; Maluszek, M.J.; Olszewski, M.B.; Zylicz, A.; Zylicz, M. Chemotherapy of HER2- and MDM2-Enriched Breast Cancer Subtypes Induces Homologous Recombination DNA Repair and Chemoresistance. Cancers 2021, 13, 4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayarre, J.; Kamieniak, M.M.; Cazorla-Jiménez, A.; Muñoz-Repeto, I.; Borrego, S.; García-Donas, J.; Hernando, S.; Robles-Díaz, L.; García-Bueno, J.M.; Ramón y Cajal, T.; et al. The NER-related gene GTF2H5 predicts survival in high-grade serous ovarian cancer patients. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 27, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.-H.; Li, J.; Chen, P.; Jiang, H.-G.; Wu, M.; Chen, Y.-C. RNA interferences targeting the Fanconi anemia/BRCA pathway upstream genes reverse cisplatin resistance in drug-resistant lung cancer cells. J. Biomed. Sci. 2015, 22, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Kothandapani, A.; Tillison, K.; Kalman-Maltese, V.; Patrick, S.M. Downregulation of XPF–ERCC1 enhances cisplatin efficacy in cancer cells. DNA Repair 2010, 9, 745–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, M.; Zhang, W.; Xiao, T.; Chen, C.-H.; Wu, A.; Wu, F.; Traugh, N.; Wang, X.; Li, Z.J.N.p. Integrative analysis of pooled CRISPR genetic screens using MAGeCKFlute. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Wang, J.; Li, M.; Wang, J.; Lv, J.; Zhang, L.; Sun, C.; Ji, J.; Yang, W.; Zhao, Z.; et al. Berberine attenuates XRCC1-mediated base excision repair and sensitizes breast cancer cells to the chemotherapeutic drugs. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 6797–6804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.-m.; Li, Z.; Han, X.-d.; Shi, J.-h.; Tu, D.-y.; Song, W.; Zhang, J.; Qiu, X.-l.; Ren, Y.; Zhen, L.-l. MiR-30e inhibits tumor growth and chemoresistance via targeting IRS1 in Breast Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, A.K.; Ajay, A.K.; Singh, S.; Bhat, M.K. Cell Cycle Regulatory Protein 5 (Cdk5) is a Novel Downstream Target of ERK in Carboplatin Induced Death of Breast Cancer Cells (Supplementary Data). Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2008, 8, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syu, J.-P.; Chi, J.-T.; Kung, H.-N. Nrf2 is the key to chemotherapy resistance in MCF7 breast cancer cells under hypoxia. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 14659–14672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Huang, J.; Feng, Y.; Li, Z.; Jiang, Y. Profiling of specific long non-coding RNA signatures identifies ST8SIA6-AS1 AS a novel target for breast cancer. J. Gene Med. 2021, 23, e3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Samanta, D.; Xiang, L.; Zhang, H.; Hu, H.; Chen, I.; Bullen, J.W.; Semenza, G.L. Chemotherapy triggers HIF-1–dependent glutathione synthesis and copper chelation that induces the breast cancer stem cell phenotype. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E4600–E4609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedeljković, M.; Tanić, N.; Prvanović, M.; Milovanović, Z.; Tanić, N. Friend or foe: ABCG2, ABCC1 and ABCB1 expression in triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer 2021, 28, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, A.; Mansoori, B.; Aghapour, M.; Shirjang, S.; Nami, S.; Baradaran, B. The Urtica dioica extract enhances sensitivity of paclitaxel drug to MDA-MB-468 breast cancer cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 83, 835–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Kohanfars, M.; Hsu, H.M.; Souda, P.; Capri, J.; Whitelegge, J.P.; Chang, H.R. Combined Phosphoproteomics and Bioinformatics Strategy in Deciphering Drug Resistant Related Pathways in Triple Negative Breast Cancer. Int. J. Proteom. 2014, 2014, 390781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, D.; Ren, X.; Han, M.; Xu, X.; Ge, X.; Gu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, S. CircUBE2D2 (hsa_circ_0005728) promotes cell proliferation, metastasis and chemoresistance in triple-negative breast cancer by regulating miR-512-3p/CDCA3 axis. Cancer Cell Int. 2020, 20, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jiang, C.; Li, H.; Lv, F.; Li, X.; Qian, X.; Fu, L.; Xu, B.; Guo, X. Elevated Aurora B expression contributes to chemoresistance and poor prognosis in breast cancer. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 751–757. [Google Scholar]

- Lemasters, J.J. Evolution of Voltage-Dependent Anion Channel Function: From Molecular Sieve to Governator to Actuator of Ferroptosis. Front. Oncol. 2017, 7, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Puerto, M.C.; Folkerts, H.; Wierenga, A.T.J.; Schepers, K.; Schuringa, J.J.; Coffer, P.J.; Vellenga, E. Autophagy Proteins ATG5 and ATG7 Are Essential for the Maintenance of Human CD34+ Hematopoietic Stem-Progenitor Cells. Stem Cells 2016, 34, 1651–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluzzi, L.; Vitale, I.; Aaronson, S.A.; Abrams, J.M.; Adam, D.; Agostinis, P.; Alnemri, E.S.; Altucci, L.; Amelio, I.; Andrews, D.W.; et al. Molecular mechanisms of cell death: Recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2018. Cell Death Differ. 2018, 25, 486–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Y.-J.; Kao, T.-Y.; Kuo, C.-L.; Fan, C.-C.; Cheng, A.N.; Fang, W.-C.; Chou, H.-Y.; Lo, Y.-K.; Chen, C.-H.; Jiang, S.S.; et al. Mitochondrial Lon sequesters and stabilizes p53 in the matrix to restrain apoptosis under oxidative stress via its chaperone activity. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inuzuka, H.; Shaik, S.; Onoyama, I.; Gao, D.; Tseng, A.; Maser, R.S.; Zhai, B.; Wan, L.; Gutierrez, A.; Lau, A.W.; et al. SCFFBW7 regulates cellular apoptosis by targeting MCL1 for ubiquitylation and destruction. Nature 2011, 471, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Z.; Zheng, J.; Xue, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, D.; Yang, C.; Ma, J.; Liu, L.; Ruan, X.; Wang, Z.; et al. NR2C2-uORF targeting UCA1-miR-627-5p-NR2C2 feedback loop to regulate the malignant behaviors of glioma cells. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.; Du, C.; Wu, J.-W.; Kyin, S.; Wang, X.; Shi, Y. Structural and biochemical basis of apoptotic activation by Smac/DIABLO. Nature 2000, 406, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Sun, B.; Gao, Y.; Niu, H.; Yuan, H.; Lou, H. STAT3 contributes to lysosomal-mediated cell death in a novel derivative of riccardin D-treated breast cancer cells in association with TFEB. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2018, 150, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.-w.; Flemington, C.; Houghton, A.B.; Gu, Z.; Zambetti, G.P.; Lutz, R.J.; Zhu, L.; Chittenden, T. Expression of bbc3, a pro-apoptotic BH3-only gene, is regulated by diverse cell death and survival signals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 11318–11323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamarin, D.; García-Sastre, A.; Xiao, X.; Wang, R.; Palese, P. Influenza Virus PB1-F2 Protein Induces Cell Death through Mitochondrial ANT3 and VDAC1. PLoS Pathog. 2005, 1, e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.-Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Xie, Z.; Zhao, X.-Y.; Sun, Y.; Kong, W.-J. The dual role of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 in modulating parthanatos and autophagy under oxidative stress in rat cochlear marginal cells of the stria vascularis. Redox Biol. 2018, 14, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubillos-Ruiz, J.R.; Bettigole, S.E.; Glimcher, L.H. Tumorigenic and Immunosuppressive Effects of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Cancer. Cell 2017, 168, 692–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.A.; So, E.Y.; Simons, A.L.; Spitz, D.R.; Ouchi, T. DNA damage induces reactive oxygen species generation through the H2AX-Nox1/Rac1 pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2012, 3, e249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, A.; Koliaraki, V.; Kollias, G. Mesenchymal MAPKAPK2/HSP27 drives intestinal carcinogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E5546–E5555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Ge, N.; Wang, X.; Sun, W.; Mao, R.; Bu, W.; Creighton, C.J.; Zheng, P.; Vasudevan, S.; An, L.; et al. Amplification and over-expression of MAP3K3 gene in human breast cancer promotes formation and survival of breast cancer cells. J. Pathol. 2014, 232, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufo, N.; Garg, A.D.; Agostinis, P. The Unfolded Protein Response in Immunogenic Cell Death and Cancer Immunotherapy. Trends Cancer 2017, 3, 643–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Man, S.M.; Karki, R.; Kanneganti, T.-D. Molecular mechanisms and functions of pyroptosis, inflammatory caspases and inflammasomes in infectious diseases. Immunol. Rev. 2017, 277, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, K. RIPK1 and RIPK3: Critical regulators of inflammation and cell death. Trends Cell Biol. 2015, 25, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghe, T.V.; Demon, D.; Bogaert, P.; Vandendriessche, B.; Goethals, A.; Depuydt, B.; Vuylsteke, M.; Roelandt, R.; Wonterghem, E.V.; Vandenbroecke, J.; et al. Simultaneous Targeting of IL-1 and IL-18 Is Required for Protection against Inflammatory and Septic Shock. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 189, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casson, C.N.; Yu, J.; Reyes, V.M.; Taschuk, F.O.; Yadav, A.; Copenhaver, A.M.; Nguyen, H.T.; Collman, R.G.; Shin, S. Human caspase-4 mediates noncanonical inflammasome activation against gram-negative bacterial pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 6688–6693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Bidere, N.; Staudt, D.; Cubre, A.; Orenstein, J.; Chan, F.K.; Lenardo, M. Competitive Control of Independent Programs of Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor-Induced Cell Death by TRADD and RIP1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006, 26, 3505–3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawlor, K.E.; Khan, N.; Mildenhall, A.; Gerlic, M.; Croker, B.A.; D’Cruz, A.A.; Hall, C.; Kaur Spall, S.; Anderton, H.; Masters, S.L.; et al. RIPK3 promotes cell death and NLRP3 inflammasome activation in the absence of MLKL. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzmán, E.A. Regulated Cell Death Signaling Pathways and Marine Natural Products That Target Them. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sanz, P.; Orgaz, L.; Fuentes, J.M.; Vicario, C.; Moratalla, R. Cholesterol and multilamellar bodies: Lysosomal dysfunction in GBA-Parkinson disease. Autophagy 2018, 14, 717–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnaiyan, A.M.; O’Rourke, K.; Tewari, M.; Dixit, V.M. FADD, a novel death domain-containing protein, interacts with the death domain of fas and initiates apoptosis. Cell 1995, 81, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-C.; Leclair, P.; Pedari, F.; Vieira, H.; Monajemi, M.; Sly, L.M.; Reid, G.S.; Lim, C.J. Integrins and ERp57 Coordinate to Regulate Cell Surface Calreticulin in Immunogenic Cell Death. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredel, M.; Scholtens, D.M.; Yadav, A.K.; Alvarez, A.A.; Renfrow, J.J.; Chandler, J.P.; Yu, I.L.Y.; Carro, M.S.; Dai, F.; Tagge, M.J.; et al. NFKBIA Deletion in Glioblastomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 364, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujikawa, K.; Nakahara, K.; Takasugi, N.; Nishiya, T.; Ito, A.; Uchida, K.; Uehara, T. S-Nitrosylation at the active site decreases the ubiquitin-conjugating activity of ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 D1 (UBE2D1), an ERAD-associated protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 524, 910–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Kang, R.; Berghe, T.V.; Vandenabeele, P.; Kroemer, G. The molecular machinery of regulated cell death. Cell Res. 2019, 29, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, K.; Shi, X.; Wang, Y.; Huang, H.; Zhuang, Y.; Cai, T.; Wang, F.; Shao, F. Cleavage of GSDMD by inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death. Nature 2015, 526, 660–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baines, C.P.; Kaiser, R.A.; Purcell, N.H.; Blair, N.S.; Osinska, H.; Hambleton, M.A.; Brunskill, E.W.; Sayen, M.R.; Gottlieb, R.A.; Dorn, G.W.; et al. Loss of cyclophilin D reveals a critical role for mitochondrial permeability transition in cell death. Nature 2005, 434, 658–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponder, K.G.; Boise, L.H. The prodomain of caspase-3 regulates its own removal and caspase activation. Cell Death Discov. 2019, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pimentel-Muiños, F.X.; Seed, B. Regulated Commitment of TNF Receptor Signaling: A Molecular Switch for Death or Activation. Immunity 1999, 11, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennelly, C.; Amaravadi, R.K. Lysosomal Biology in Cancer. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1594, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargeant, T.J.; Lloyd-Lewis, B.; Resemann, H.K.; Ramos-Montoya, A.; Skepper, J.; Watson, C.J. Stat3 controls cell death during mammary gland involution by regulating uptake of milk fat globules and lysosomal membrane permeabilization. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014, 16, 1057–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteleone, M.; Stanley, A.C.; Chen, K.W.; Brown, D.L.; Bezbradica, J.S.; von Pein, J.B.; Holley, C.L.; Boucher, D.; Shakespear, M.R.; Kapetanovic, R.; et al. Interleukin-1β; Maturation Triggers Its Relocation to the Plasma Membrane for Gasdermin-D-Dependent and -Independent Secretion. Cell Rep. 2018, 24, 1425–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gröschel, M.; Basta, D.; Ernst, A.; Mazurek, B.; Szczepek, A.J. Acute Noise Exposure Is Associated with Intrinsic Apoptosis in Murine Central Auditory Pathway. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, T.; Zhang, X. Identification of a Pyroptosis-Related Prognostic Signature Combined with Experiments in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 822503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rager, J.E. Chapter 8—The Role of Apoptosis-Associated Pathways as Responders to Contaminants and in Disease Progression. In Systems Biology in Toxicology and Environmental Health; Fry, R.C., Ed.; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 187–205. [Google Scholar]

- Kuriakose, T.; Man, S.M.; Subbarao Malireddi, R.K.; Karki, R.; Kesavardhana, S.; Place, D.E.; Neale, G.; Vogel, P.; Kanneganti, T.-D. ZBP1/DAI is an innate sensor of influenza virus triggering the NLRP3 inflammasome and programmed cell death pathways. Sci. Immunol. 2016, 1, aag2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano-del Valle, A.; Anel, A.; Naval, J.; Marzo, I. Immunogenic Cell Death and Immunotherapy of Multiple Myeloma. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulla, A.; Morelli, E.; Hideshima, T.; Samur, M.K.; Bianchi, G.; Fulciniti, M.; Munshi, N.; Anderson, K.C. Optimizing Mechanisms for Induction of Immunogenic Cell Death to Improve Patient Outcome in Multiple Myeloma. Blood 2018, 132, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, T.; Tröder, S.E.; Bakka, K.; Korwitz, A.; Richter-Dennerlein, R.; Lampe, P.A.; Patron, M.; Mühlmeister, M.; Guerrero-Castillo, S.; Brandt, U.; et al. The m-AAA Protease Associated with Neurodegeneration Limits MCU Activity in Mitochondria. Mol. Cell 2016, 64, 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mufti, A.R.; Burstein, E.; Duckett, C.S. XIAP: Cell death regulation meets copper homeostasis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2007, 463, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aichberger, K.J.; Mayerhofer, M.; Krauth, M.-T.; Vales, A.; Kondo, R.; Derdak, S.; Pickl, W.F.; Selzer, E.; Deininger, M.; Druker, B.J.; et al. Low-Level Expression of Proapoptotic Bcl-2–Interacting Mediator in Leukemic Cells in Patients with Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: Role of BCR/ABL, Characterization of Underlying Signaling Pathways, and Reexpression by Novel Pharmacologic Compounds. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 9436–9444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, M.C.; Maso, V.; Torello, C.O.; Ferro, K.P.; Saad, S.T.O. The polyphenol quercetin induces cell death in leukemia by targeting epigenetic regulators of pro-apoptotic genes. Clin. Epigenetics 2018, 10, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhshan, A.; Chen, Z.; Van Waes, C. Therapeutic Small Molecules Target Inhibitor of Apoptosis Proteins in Cancers with Deregulation of Extrinsic and Intrinsic Cell Death Pathways. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 1379–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Orsi, B.; Mateyka, J.; Prehn, J.H.M. Control of mitochondrial physiology and cell death by the Bcl-2 family proteins Bax and Bok. Neurochem. Int. 2017, 109, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.J.; Tait, S.W.G. Targeting BCL-2 regulated apoptosis in cancer. Open Biol. 2018, 8, 180002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.-C.; Kanai, M.; Inoue-Yamauchi, A.; Tu, H.-C.; Huang, Y.; Ren, D.; Kim, H.; Takeda, S.; Reyna, D.E.; Chan, P.M.; et al. An interconnected hierarchical model of cell death regulation by the BCL-2 family. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015, 17, 1270–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letai, A.; Bassik, M.C.; Walensky, L.D.; Sorcinelli, M.D.; Weiler, S.; Korsmeyer, S.J. Distinct BH3 domains either sensitize or activate mitochondrial apoptosis, serving as prototype cancer therapeutics. Cancer Cell 2002, 2, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frudd, K.; Burgoyne, T.; Burgoyne, J.R. Oxidation of Atg3 and Atg7 mediates inhibition of autophagy. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Zhou, X.-J.; Zhang, H. Exploring the Role of Autophagy-Related Gene 5 (ATG5) Yields Important Insights Into Autophagy in Autoimmune/Autoinflammatory Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durgan, J.; Florey, O. Cancer cell cannibalism: Multiple triggers emerge for entosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Mol. Cell Res. 2018, 1865, 831–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, F.F.S.; Vanyai, H.K.; Cowan, A.D.; Delbridge, A.R.D.; Whitehead, L.; Grabow, S.; Czabotar, P.E.; Voss, A.K.; Strasser, A. Embryogenesis and Adult Life in the Absence of Intrinsic Apoptosis Effectors BAX, BAK, and BOK. Cell 2018, 173, 1217–1230.e1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, K.; Wickliffe, K.E.; Maltzman, A.; Dugger, D.L.; Reja, R.; Zhang, Y.; Roose-Girma, M.; Modrusan, Z.; Sagolla, M.S.; Webster, J.D.; et al. Activity of caspase-8 determines plasticity between cell death pathways. Nature 2019, 575, 679–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, G.R.; Bruckman, R.S.; Chu, Y.-L.; Trout, R.N.; Spector, S.A. SMAC Mimetics Induce Autophagy-Dependent Apoptosis of HIV-1-Infected Resting Memory CD4+ T Cells. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 24, 689–702.e687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Yang, J.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Luo, W.; Fung, K.-M.; Xu, C.; Bronze, M.S.; Houchen, C.W.; et al. Circular RNA ANAPC7 Inhibits Tumor Growth and Muscle Wasting via PHLPP2–AKT–TGF-β Signaling Axis in Pancreatic Cancer. Gastroenterology 2022, 162, 2004–2017.e2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Williamson, A.; Banerjee, S.; Philipp, I.; Rape, M. Mechanism of Ubiquitin-Chain Formation by the Human Anaphase-Promoting Complex. Cell 2008, 133, 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, K.; Mizuguchi, M.; Harata, A.; Itoh, G.; Tanaka, K. Nocodazole induces mitotic cell death with apoptotic-like features in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 2010, 584, 2387–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waring, P.; Müllbacher, A. Cell death induced by the Fas/Fas ligand pathway and its role in pathology. Immunol. Cell Biol. 1999, 77, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Kelly, T.K.; Jones, P.A. Epigenetics in cancer. Carcinogenesis 2010, 31, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippakopoulos, P.; Qi, J.; Picaud, S.; Shen, Y.; Smith, W.B.; Fedorov, O.; Morse, E.M.; Keates, T.; Hickman, T.T.; Felletar, I. Selective inhibition of BET bromodomains. Nature 2010, 468, 1067–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Li, M.; Wan, X.; Jin, X.; Chen, S.; Yu, C.; Li, Y. Effect of miR-34a in regulating steatosis by targeting PPARα expression in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 13729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.S.; Tiwari, A.K. Multidrug resistance proteins (MRPs/ABCCs) in cancer chemotherapy and genetic diseases. FEBS J. 2011, 278, 3226–3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.H.; Kuo, M.T. Role of glutathione in the regulation of Cisplatin resistance in cancer chemotherapy. Met. Based Drugs 2010, 2010, 430939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, W.; Mossmann, D.; Kleemann, J.; Mock, K.; Meisinger, C.; Brummer, T.; Herr, R.; Brabletz, S.; Stemmler, M.P.; Brabletz, T. ZEB1 turns into a transcriptional activator by interacting with YAP1 in aggressive cancer types. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickson, I.; Zhao, Y.; Richardson, C.J.; Green, S.J.; Martin, N.M.; Orr, A.I.; Reaper, P.M.; Jackson, S.P.; Curtin, N.J.; Smith, G.C. Identification and characterization of a novel and specific inhibitor of the ataxia-telangiectasia mutated kinase ATM. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 9152–9159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.; Gao, L.; Aguila, B.; Kalvala, A.; Otterson, G.A.; Villalona-Calero, M.A. Fanconi anemia repair pathway dysfunction, a potential therapeutic target in lung cancer. Front. Oncol. 2014, 4, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittaker, S.R.; Mallinger, A.; Workman, P.; Clarke, P.A. Inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinases as cancer therapeutics. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 173, 83–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinge, J.-M.; Giraud-Panis, M.-J.; Leng, M. Interstrand cross-links of cisplatin induce striking distortions in DNA. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1999, 77, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, K.; Ishiai, M.; Horikawa, K.; Fukagawa, T.; Takata, M.; Takisawa, H.; Kanemaki, M.T. Mcm8 and Mcm9 form a complex that functions in homologous recombination repair induced by DNA interstrand crosslinks. Mol. Cell 2012, 47, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helderman, N.C.; Terlouw, D.; Bonjoch, L.; Golubicki, M.; Antelo, M.; Morreau, H.; van Wezel, T.; Castellví-Bel, S.; Goldberg, Y.; Nielsen, M. Molecular functions of MCM8 and MCM9 and their associated pathologies. iScience 2023, 26, 106737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.; Kmieciak, M.; Leng, Y.; Lin, H.; Rizzo, K.A.; Dumur, C.I.; Ferreira-Gonzalez, A.; Dai, Y.; et al. A regimen combining the Wee1 inhibitor AZD1775 with HDAC inhibitors targets human acute myeloid leukemia cells harboring various genetic mutations. Leukemia 2015, 29, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Yin, J.; Fang, Y.; Chen, J.; Jeong, K.J.; Chen, X.; Vellano, C.P.; Ju, Z.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, D.; et al. BRD4 Inhibition Is Synthetic Lethal with PARP Inhibitors through the Induction of Homologous Recombination Deficiency. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 401–416.e408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, B.C.; Li, Y.; Murray, D.; Liu, Y.; Nieto, Y.; Champlin, R.E.; Andersson, B.S. Combination of a hypomethylating agent and inhibitors of PARP and HDAC traps PARP1 and DNMT1 to chromatin, acetylates DNA repair proteins, down-regulates NuRD and induces apoptosis in human leukemia and lymphoma cells. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Sun, R.; Shi, H.; Chapman, N.M.; Hu, H.; Guy, C.; Rankin, S.; Kc, A.; Palacios, G.; Meng, X. VDAC2 loss elicits tumour destruction and inflammation for cancer therapy. Nature 2025, 640, 1062–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, H.S.; Li, M.X.; Tan, I.K.; Ninnis, R.L.; Reljic, B.; Scicluna, K.; Dagley, L.F.; Sandow, J.J.; Kelly, G.L.; Samson, A.L. VDAC2 enables BAX to mediate apoptosis and limit tumor development. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.Q.; De Marchi, T.; Timmermans, A.M.; Beekhof, R.; Trapman-Jansen, A.M.; Foekens, R.; Look, M.P.; van Deurzen, C.H.; Span, P.N.; Sweep, F.C. Ferritin heavy chain in triple negative breast cancer: A favorable prognostic marker that relates to a cluster of differentiation 8 positive (CD8+) effector T-cell response. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2014, 13, 1814–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, P.; Yang, F.; Qi, H.; Hu, Y.; Zhu, S.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, C.; Hou, C.; Yu, J. Alteration of MDM2 by the Small Molecule YF438 Exerts Antitumor Effects in Triple-Negative Breast CancerYF438 Exerts Promising Antitumor Effects on TNBC via MDM2. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 4027–4040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, M.M.; McConnery, J.R.; Hoskin, D.W. [10]-Gingerol, a major phenolic constituent of ginger root, induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in triple-negative breast cancer cells. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2017, 102, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Luo, B.; Wu, X.; Guan, F.; Yu, X.; Zhao, L.; Ke, X.; Wu, J.; Yuan, J. Cisplatin induces pyroptosis via activation of MEG3/NLRP3/caspase-1/GSDMD pathway in triple-negative breast cancer. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 17, 2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Dataset | Sample Size | Platform | Source | Publication | Genes and Pathways Discovered in Breast Cancer Chemoresistance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSE28844 | 61 | Affymetrix (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) | Patient | Laura et al., 2013 [31] | chemoresistance-associated gene shows enrichment in Wnt, HIF1, p53, and Rho GTPases signaling pathways |

| GSE18728 | 61 | Affymetrix (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) | Patient | Korde et al., 2010 [32] | MAP-2, MACF1, VEGF-B, EGFR showed upregulation in poor responder after chemotherapy |

| GSE32646 | 115 | Affymetrix (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) | Patient | Miyake et al., 2012 [33] | GSTP1 expression predicts poor response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patient with ER-negative breast cancer |

| GSE36133 (CCLE) | 917 (21 TNBC) | Affymetrix (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) | Cell line | Barretina et al., 2010 [30] | . |

| Gene | Pathway | Validation Method | Inhibitor | Drug Development Status | Chemotherapy Drug | Cancer Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDC25B [52] | Cell cycle regulation, DNA damage response | In vitro (siRNA), In vivo (xenograft model) | Thiostrepton, FDI-6, Siomycin A | Preclinical | Paclitaxel, Cisplatin | Platinum-resistant ovarian cancer |

| NCF1 [53] | Autophagy, ROS production | In vitro (siRNA) | Ginsenoside Ro | Preclinical | 5-fluorouracil | Esophageal cancer |

| USP22, HSP90AB1 [54] | HSP90 regulation and ubiquitin pathway | In vitro (siRNA), In vivo (xenograft model) | Ganetespib, AT13387 | Phase II trials | Irinotecan | Mammary and colorectal cancer |

| DNMT1 [55] | DNA methylation | In vitro (siRNA), In vivo (mice model, xenograft with gene knockdown) | Decitabine | Clinical (used for other cancer types) | Decitabine | Triple-negative breast cancer |

| BCL2L1 [56] | Apoptosis | In vitro (cell lines), In vivo (mice model) | BikDD, Lapatinib | Preclinical | Doxorubicin | breast cancer |

| RUNX2 [57] | BET inhibition | In vitro (siRNA), In vivo (xenograft model, CRISPR knockout) | BET inhibitors: JQ1, I-BET762 | Preclinical, Phase I/II | Cisplatin, Taxanes | Triple-negative breast cancer |

| HSP90 [58] | Chaperone protein function | In vitro (siRNA), In vivo (xenograft model) | 17-AAG, PU-H71 | Phase II/III trials | Doxorubicin | HER2-negative breast cancer |

| PPIA [59] | miRNA regulation | In vitro (miRNA-192-5p mimic) | - | - | Doxorubicin | Breast cancer |

| RUNX1 [60] | YAP signaling pathway | In vitro (shRNA knockdown), In vivo (xenograft) | - | - | Doxorubicin | Breast cancer |

| NBN [61] | DNA repair, homologous recombination | In vitro (siRNA) | - | - | Doxorubicin, Paclitaxel, Carboplatin | HER2- and MDM2-enriched breast cancer subtypes |

| GTF2H5 [62] | Nucleotide excision repair (NER) | In vitro | - | - | Carboplatin, Paclitaxel | High-grade serous ovarian cancer |

| FANCA, FANCG [63] | DNA damage repair, Fanconi anemia/BRCA pathway | In vitro (siRNA) | - | - | Cisplatin | Drug-resistant lung cancer |

| ERCC1 [64] | Nucleotide excision repair | In vitro (siRNA), In vivo (xenograft model) | - | - | Cisplatin | Various cancer types |

| XRCC1 [65] | DNA repair | In vitro (siRNA) | Triptolide | Preclinical | Cisplatin | Triple-negative breast cancer |

| XRCC1 [66] | Base excision repair | In vitro (siRNA) | Berberine | Preclinical | Epirubicin, Doxorubicin, Cyclophosphamide, 5-fluorouracil, Docetaxel, Cisplatin | Breast cancer |

| IRS1 [67] | PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling | In vitro (miRNA and inhibitor) | Y-29794 | Preclinical | Paclitaxel, Carboplatin, Gemcitabine, Doxorubicin, Cisplatin | Triple-negative breast cancer |

| Cdk5 [68] | Cell cycle regulation, carboplatin-induced cell death | In vitro (siRNA) | - | - | Carboplatin | Breast cancer |

| FANCL [63] | Fanconi anemia/BRCA pathway | In vitro (siRNA) | - | - | Cisplatin | Lung cancer |

| NFE2L2 [69] | Chemotherapy resistance, hypoxia response | In vitro (siRNA, hypoxia exposure) | - | - | Cisplatin, Doxorubicin, and Etoposide | Breast cancer |

| NBN [61] | Homologous recombination DNA repair | In vitro (immuno-fluorescence, Western blot) | - | - | Docetaxel, Doxorubicin, and Cyclophosphamide | Breast cancer |

| HIST1H2BJ [70,71] | Glutathione synthesis, copper chelation | In vitro (siRNA), In vivo (mice) | - | - | Doxorubicin, Paclitaxel, 5-fluorouracil | Breast cancer |

| ABCC1 [72] | Drug efflux transporters | In vitro (siRNA) | - | - | Doxorubicin, Paclitaxel, Cisplatin | Triple-negative breast cancer |

| ZEB2 [73] | ATM activation | In vitro (siRNA) | - | - | Doxorubicin, Paclitaxel, Cisplatin | Breast cancer |

| CDK5 [74] | Drug resistance-related pathways | In vitro (siRNA) | - | - | Paclitaxel, Cisplatin, and Doxorubicin | Triple-negative breast cancer |

| CDCA3 [75] | Cell proliferation, metastasis, chemoresistance | In vitro (siRNA, RT-qPCR) | - | - | Paclitaxel, Cisplatin, and Doxorubicin | Triple-negative breast cancer |

| CDC25B [52] | Cell cycle regulation | In vitro (siRNA) | - | - | Paclitaxel, Cisplatin | Platinum-resistant ovarian cancer |

| ATM [76] | Cell cycle regulation | In vitro (siRNA), In vivo (xenograft mice) | - | - | Taxanes | Breast cancer |

| Genes | Cell_Death_Mode | Synonyms | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| VDAC3 | Ferroptosis | VDAC-3, HD-VDAC3, HVDAC | Lemasters 2017 [77] |

| VDAC2 | Ferroptosis | VDAC-2, HVDAC2, POR | Lemasters 2017 [77] |

| ATG7 | Autophagy | Ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1-like protein, ubiquitin-like modifier-activating enzyme ATG7 | Gomez-Puerto et al., 2016 [78] |

| UBE2E1 | Mitotic_CD | UBCH6 | Galluzzi et al., 2018 [79] |

| TP53 | MPT | Tumor protein 53, P53 | Sung et al., 2018 [80] |

| MCL1 | Apoptosis | TM, EAT, MCL1L1 | Inuzuka et al., 2011 [81] |

| NR2C2 | Apoptosis | TAK1, TR4 | Fan et al., 2018 [82] |

| DIABLO | Apoptosis | SMAC, DFNA64 | Chai et al., 2000 [83] |

| STAT3 | Parthanatos | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (acute-phase response factor), DNA-binding protein APRF | Li et al., 2018 [84] |

| BBC3 | Apoptosis | PUMA, JFY1 | Han et al., 2001 [85] |

| VDAC1 | MPT | PORIN, VDAC-1 | Zamarin et al., 2005 [86] |

| PARP1 | Parthanatos | Poly [ADP-Ribose] Polymerase 1, Poly [ADP-Ribose] Synthase 1, EC 2.4.2.30, ADPRT 1, PARP-1 | Jiang et al., 2018 [87] |

| EIF2AK3 | Parthanatos | PERK, PEK, HsPEK | Cubillos-Ruiz et al., 2017 [88] |

| NOXA1 | Apoptosis | p51NOX, NY-CO-31 | Kang et al., 2012 [89] |

| MAPKAPK2 | Apoptosis | MK2, MK-2, MAPKAP-K2 | Henriques et al., 2018 [90] |

| MAP3K3 | Efferocytosis | MAPKKK3, MEKK3 | Fan et al., 2014 [91] |

| ERN1 | Parthanatos | Inositol-requiring protein 1, Inositol-requiring enzyme 1 | Rufo et al., 2017 [92] |

| CASP1 | Pyroptosis | Inflammasome (Nalp3, Asc, Casp1) | Man et al., 2017 [93] |

| RIPK1 | Apoptosis | IMD57, RIP, RIP1 | Newton 2015 [94] |

| TICAM1 | Apoptosis | IIAE6, TRIF, MyD88-3 | Galluzzi et al., 2018 [79] |

| IL18 | Pyroptosis | IFIF, IL-18, IL1F4 | Berghe et al., 2014 [95] |

| CASP4 | Pyroptosis | ICEREL-II, ICH-2 | Casson et al., 2015 [96] |

| TRADD | Apoptosis | Hs. 89862 | Zheng et al., 2006 [97] |

| MLKL | Necroptosis | hMLKL | Lawlor et al. [98] |

| HK1 | Parthanatos | HK1-Tb, HK1-Tc, HMSNR, HXK1 | Guzmán 2019 [99] |

| GBA | Autophagy | GLCM_HUMAN, GLUC | García-Sanz et al., 2018 [100] |

| FADD | Apoptosis | GIG3, MORT | Chinnaiyan et al., 1995 [101] |

| RAPGEF3 | MPT | EPAC1, HSU79275, CAP-GEFI | Galluzzi et al., 2018 [79] |

| PDIA3 | Parthanatos | Endoplasmic reticulum resident protein 60, protein disulfide isomerase-associated 3 | Liur et al., 2019 [102] |

| NFKBIA | Efferocytosis | EDAID2, IKBA, MAD-3 | Bredel et al., 2010 [103] |

| UBE2D1 | Mitotic_CD | E1 (17)KB1, SFT, UBC4/5 | Fujikawa et al., 2020 [104] |

| CDH1 | Parthanatos | Epithelial cadherin, CAM 120/80, CDHE, UVO | Tang et al., 2019 [105] |

| GSDMD | Pyroptosis | DF5L, DFNA5L | Shi et al., 2015 [106] |

| PPIF | Apoptosis | CYP3, CypD, CyP-M | Baines et al., 2005 [107] |

| CASP3 | Apoptosis | CPP32, CPP32B | Ponder et al., 2019 [108] |

| TNFRSF1B | Efferocytosis | CD120b, TBPII, TNF-R-II, TNFR2 | Pimentel-Muiños et al., 1999 [109] |

| TNFRSF1A | Apoptosis | CD120a, FPF, TBP1, TNF-R, R55 | Galluzzi et al., 2018 [79] |

| LAMP1 | Parthanatos | CD107 antigen-like family member A, LAMP-1, lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 | Fennelly et al., 2017 [110] |

| CTSL | Lysosomal_CD | CATL1, MEP, CTSL | Sargeant et al., 2014 [111] |

| IL1B | Pyroptosis | Catabolin, IL-1 beta, IL1F2, pro-interleukin-1-beta | Monteleone et al., 2018 [112] |

| CASP6 | Apoptosis | CASP3/6/7, caspase 3, 6, 7, caspase-3, -6, and -7 | Gröschel et al., 2018 [113] |

| SCAF11 | Pyroptosis | CASP11, SFRS2IP, SIP1, SRRP129 | Li et al., 2022 [114] |

| CASP7 | Apoptosis | CASP-7, CMH-1, ICE-LAP3 | Rager 2015 [115] |

| MAVS | Pyroptosis | CARDIF, IPS-1, IPS1, VISA | Kuriakose et al., 2016 [116] |

| ATF6 | Parthanatos | CAMP-dependent transcription factor ATF-6 alpha, activating transcription factor 6 alpha, ATF6-Alph | Serrano-del Valle et al., 2019 [117] |

| CALR | Parthanatos | Calregulin, CRP55, ERp60, HACBP, Grp60 | Gullai et al., 2018 [118] |

| MCU | MPT | C10orf42, CCDC109A, HsMCU | König et al., 2016 [119] |

| XIAP | Apoptosis | BIRC4, API3, IPA-3, XLP2, hIAP-3 | Mufti et al., 2007 [120] |

| BCL2L11 | Apoptosis | BIM, BAM, BOD, | Alvarez et al., 2018 [121,122] |

| BID | Apoptosis | BID isoform L(2), BID isoform Si6, FP497 | Derakhshan et al., 2017 [123] |

| BOK | Apoptosis | BCL2L9 | D’Orsi et al., 2017 [124] |

| BCL2 | Apoptosis | BCL2, apoptosis regulator, B-cell CLL/Lymphoma, PPP1R50, Bcl-2 | Campbell et al., 2018 [125] |

| BCL2L1 | Apoptosis | BCL-XL, BCLX, BCL2L | Chen et al., 2015 [126] |

| BAD | Apoptosis | BBC2, BCL2L8 | Letai et al., 2002 [127] |

| ATG3 | Autophagy | Autophagy-related protein 3, APG3L, HApg, APG3 | Frudd et al., 2018 [128] |

| ATG5 | Autophagy | Autophagy protein 5, ATG5 autophagy-related 5 homolog | Ye et al., 2018 [129] |

| RHOA | Parthanatos | ARH12, RHO12, ARHA | Durgan et al., 2018 [130] |

| BAX | Apoptosis | Apoptosis regulator BAX, Bcl-2-like protein 4, Bcl2-L-4 | Ke et al., 2018 [131] |

| CASP8 | Apoptosis | APLS2B, CAP4, FLICE | Newton et al., 2019 [132] |

| BIRC2 | Autophagy | API1, MIHB, baculoviral IAP repeat-containing 2 | Campbell et al., 2018 [133] |

| ANAPC7 | Mitotic_CD | APC7 | Shi et al., 2022 [134] |

| ANAPC10 | Mitotic_CD | APC10, DOC1 | Jin et al., 2008 [135] |

| CDC26 | Mitotic_CD | ANAPC12, APC12 | Endo et al., 2010 [136] |

| FAS | Apoptosis | ALPS1A, APT1, CD95, APO-1 | Waring et al., 1999 [137] |

| Sample | Reads | Mapped | Mapped % | Zero_ Counts | Zero_ Counts% | Gini_ Index | Above_ Threshold | Above_ Threshold% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Library/Plasmid | 9,272,549 | 8,159,448 | 88.00 | 141 | 0.27 | 0.05 | 48,921 | 92.48 |

| T0_1 | 12,431,419 | 11,383,720 | 91.57 | 892 | 1.69 | 0.06 | 47,101 | 89.04 |

| T0_2 | 15,647,051 | 14,281,485 | 91.27 | 722 | 1.36 | 0.06 | 47,669 | 90.11 |

| T0_3 | 15,104,601 | 13,610,181 | 90.11 | 1371 | 2.59 | 0.05 | 47,547 | 89.88 |

| Tend_1 | 10,004,498 | 9,114,027 | 91.10 | 109 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 50,658 | 95.76 |

| Tend_2 | 15,386,447 | 13,994,094 | 90.95 | 48 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 51,875 | 98.06 |

| Tend_3 | 15,837,762 | 14,264,603 | 90.07 | 39 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 51,866 | 98.05 |

| Name | Pathway | Drug Bank ID | Inhibitor Name | Previous Study in TNBC | Inhibitors of Gene Pairs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTH1 | Autophagy | DB00852 | Pseudo-ephedrine | Prognostic marker [155] | YF438 (HDAC1) |

| HDAC1 | Cell cycle | DB02546 | YF438 | anti-TNBC activity [156] | Pseudoephedrine (FTH1), Fostamatinib (MAP3K3), Aluminum monostearate (VDAC2), Bryostatin 1 (DIABLO) |

| MAP3K3 | Effero-cytosis | DB12010 | Fostamatinib | -- | YF438 (HDAC1), Aluminum monostearate (VDAC2) |

| DIABLO | Apoptosis | DB11752 | Bryostatin 1 | anti-TNBC activity [157] | YF438 (HDAC1), Aluminum monostearate (VDAC2) |

| VDAC2 | Ferroptosis | DB01375 | Aluminum monostearate | -- | Bryostatin 1 (DIABLO), YF438 (HDAC1), Fostamatinib (MAP3K3) |

| CASP1 | Pyroptosis | DB00945 | Acetylsalicylic acid | anti-TNBC activity [158] | YF438 (HDAC1), Aluminum monostearate (VDAC2), Fostamatinib (MAP3K3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shao, S.; Li, S.; Huo, Y.; Tang, S.; Gökbağ, B.; Fan, K.; Huang, Y.; Wang, L.; Nagy, G.; Parvin, J.; et al. CRISPR-Cas9 Genome and Double-Knockout Screening to Identify Novel Therapeutic Targets for Chemoresistance in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancers 2025, 17, 3876. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233876

Shao S, Li S, Huo Y, Tang S, Gökbağ B, Fan K, Huang Y, Wang L, Nagy G, Parvin J, et al. CRISPR-Cas9 Genome and Double-Knockout Screening to Identify Novel Therapeutic Targets for Chemoresistance in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3876. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233876

Chicago/Turabian StyleShao, Shuai, Shangjia Li, Yang Huo, Shan Tang, Birkan Gökbağ, Kunjie Fan, Yirui Huang, Lingling Wang, Gregory Nagy, Jeffrey Parvin, and et al. 2025. "CRISPR-Cas9 Genome and Double-Knockout Screening to Identify Novel Therapeutic Targets for Chemoresistance in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3876. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233876

APA StyleShao, S., Li, S., Huo, Y., Tang, S., Gökbağ, B., Fan, K., Huang, Y., Wang, L., Nagy, G., Parvin, J., Stover, D., Cheng, L., & Li, L. (2025). CRISPR-Cas9 Genome and Double-Knockout Screening to Identify Novel Therapeutic Targets for Chemoresistance in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancers, 17(23), 3876. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233876