The Role of Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells in the Immune Contexture of TP53-Mutated High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Cohort Definition

2.2. Functional Classification of TP53 Mutation

2.3. Dendritic Cell Gene Signature Scoring and TIME Characterization

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Use of Generative AI

3. Results

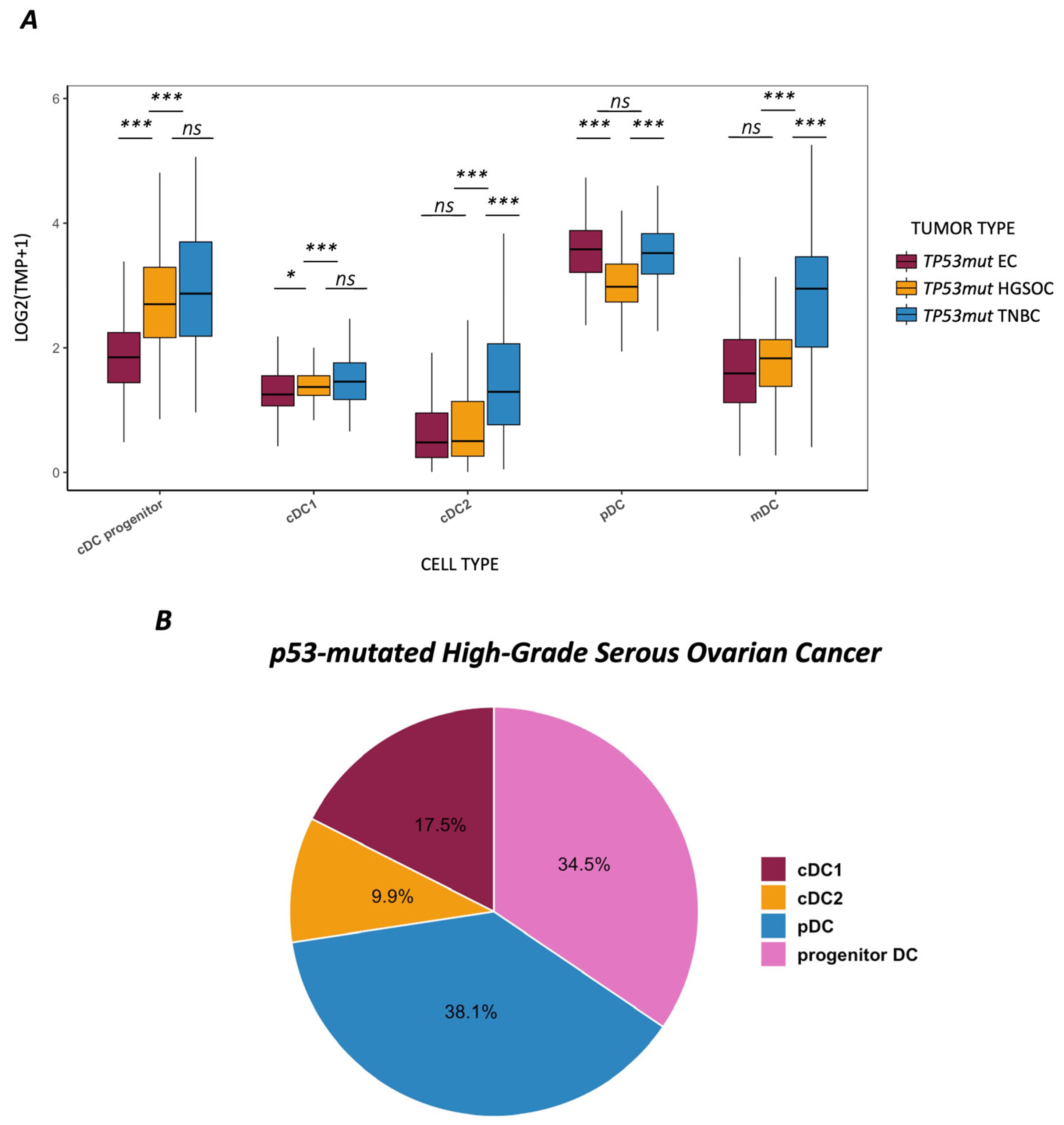

3.1. Dendritic Cell Landscape Across TP53-Mutated Tumor Entities

3.2. Interferon Signaling and Immune Correlations in HGSOC

3.3. Prognostic Relevance of pDCs in HGSOC

3.4. Tumor Mutational Burden and TP53 Mutation Characteristics

3.5. Exploratory Analysis of TP53-Wildtype Tumors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| APC | Antigen-presenting cells |

| BRCA1/2 | Breast Cancer gene 1, Breast Cancer gene 2 |

| cDC | Conventional dendritic cell |

| cDC1 | Conventional dendritic cell type 1 |

| cDC2 | Conventional dendritic cell type 2 |

| cGAS | Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| C1QA | Complement component 1q subcomponent subunit A |

| CXCL1 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1 |

| DC | Dendritic cell |

| EC | Endometrial cancer |

| ER | Estrogen receptor |

| FIGO | International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics |

| FOXP3 | Forkhead box P3 |

| GOF | Gain-of-function |

| GSVA | Gene set variation analysis |

| HGSOC | High-grade serous ovarian cancer |

| HER2 | Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| ICI | Immune checkpoint inhibitor |

| IFN | Interferon |

| INS | Insertion |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| LOF | Loss-of-function |

| MLH1 | MutL homolog 1 |

| Mb | Megabase |

| MSI | Microsatellite instability |

| NA | Not applicable |

| NK cell | Natural killer cell |

| NLS | Nuclear localization signal |

| OS | Overall survival |

| PD-1 | Programmed cell death protein 1 |

| PD-L1 | Programmed death-ligand 1 |

| pDC | Plasmacytoid dendritic cell |

| PFS | Progression-free survival |

| POLE | DNA polymerase epsilon |

| PR | Progesterone receptor |

| RNA | Ribonucleic Acid |

| RSEM | RNA-Seq by Expectation Maximization |

| SNP | Single nucleotide polymorphism |

| STING | Stimulator of interferon genes |

| TCGA | The Cancer Genome Atlas |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor beta |

| TIME | Tumor immune microenvironment |

| TMB | Tumor mutational burden |

| TNBC | Triple-negative breast cancer |

| TP53 | Tumor protein p53 gene |

| TP53mut | TP53-mutated |

| TPM | Transcripts per million |

| Treg | Regulatory T cell |

| Wnt | Wingless/Integrated signaling pathway |

| XBP1 | X-box binding protein 1 |

References

- Lane, D.P. Cancer. p53, guardian of the genome. Nature 1992, 358, 15–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsulami, A.F. Mutational Disruption of TP53: A Structural Approach to Understanding Chemoresistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abuetabh, Y.; Wu, H.H.; Chai, C.; Al Yousef, H.; Persad, S.; Sergi, C.M.; Leng, R. DNA damage response revisited: The p53 family and its regulators provide endless cancer therapy opportunities. Exp. Mol. Med. 2022, 54, 1658–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandoth, C.; McLellan, M.D.; Vandin, F.; Ye, K.; Niu, B.; Lu, C.; Xie, M.; Zhang, Q.; McMichael, J.F.; Wyczalkowski, M.A.; et al. Mutational landscape and significance across 12 major cancer types. Nature 2013, 502, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, M.R.; Chase, D.M.; Slomovitz, B.M.; Christensen, R.D.; Novák, Z.; Black, D.; Gilbert, L.; Sharma, S.; Valabrega, G.; Landrum, L.M.; et al. Dostarlimab for Primary Advanced or Recurrent Endometrial Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 2145–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskander, R.N.; Sill, M.W.; Beffa, L.; Moore, R.G.; Hope, J.M.; Musa, F.B.; Mannel, R.; Shahin, M.S.; Cantuaria, G.H.; Girda, E.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Advanced Endometrial Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 2159–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, J.-E.; Pujade-Lauraine, E.; Oaknin, A.; Belin, L.; Leitner, K.; Cibula, D.; Denys, H.; Rosengarten, O.; Rodrigues, M.; de Gregorio, N.; et al. Atezolizumab Combined With Bevacizumab and Platinum-Based Therapy for Platinum-Sensitive Ovarian Cancer: Placebo-Controlled Randomized Phase III ATALANTE/ENGOT-ov29 Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 4768–4778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujade-Lauraine, E.; Fujiwara, K.; Ledermann, J.A.; Oza, A.M.; Kristeleit, R.; Ray-Coquard, I.-L.; Richardson, G.E.; Sessa, C.; Yonemori, K.; Banerjee, S.; et al. Avelumab alone or in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone in platinum-resistant or platinum-refractory ovarian cancer (JAVELIN Ovarian 200): An open-label, three-arm, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 1034–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhawech-Fauceglia, P.; McCarthy, D.; Tonooka, A.; Scambia, G.; Garcia, Y.; Dundr, P.; Mills, A.M.; Moore, K.; Sanada, S.; Bradford, L.; et al. The association of histopathologic features after neoadjuvant chemo-immunotherapy with clinical outcome: Sub-analyses from the randomized double-blinded, placebo-controlled, Phase III IMagyn050/GOG3015/ENGOT-ov39 study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2024, 186, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, J.; Cescon, D.W.; Rugo, H.S.; Nowecki, Z.; Im, S.-A.; Yusof, M.M.; Gallardo, C.; Lipatov, O.; Barrios, C.H.; Holgado, E.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus placebo plus chemotherapy for previously untreated locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (KEYNOTE-355): A randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 3 clinical trial. Lancet 2020, 396, 1817–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorsson, V.; Gibbs, D.L.; Brown, S.D.; Wolf, D.; Bortone, D.S.; Ou Yang, T.H.; Porta-Pardo, E.; Gao, G.F.; Plaisier, C.L.; Eddy, J.A.; et al. The Immune Landscape of Cancer. Immunity 2018, 48, 812–830.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steger, K.; Fiegl, H.; Feroz, B.; Leitner, K.; Tsibulak, I.; Marth, C.; Hackl, H.; Zeimet, A.G. Differences in immunogenicity of TP53-mutated cancers with low tumor mutational burden (TMB) A study on TP53mut endometrial-, ovarian- and triple-negative breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2025, 219, 115320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Zhu, X.; Zhong, L.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yu, H.; Yang, P.; Chen, S.; Huang, H.; et al. Drug resistance in ovarian cancer: From mechanism to clinical trial. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, N.R.; Kamitani, H.Z.; de Souza Wagner, P.H.; Matheus, G.; Talah, B.A.D.; Tanimoto, L.E.; Silva, A.P.S.; Monteiro, J.M.L.; Araujo Junior, E.; Baracat, E.C.; et al. Impact of TP53 somatic mutations on prognosis in endometrial cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2025; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitri, Z.I.; Abuhadra, N.; Goodyear, S.M.; Hobbs, E.A.; Kaempf, A.; Thompson, A.M.; Clark, J.; Stickeler, E.; Schmidt, M.; Ashworth, A.; et al. Impact of TP53 mutations in Triple Negative Breast Cancer. npj Precis. Oncol. 2022, 6, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koboldt, D.C.; Fulton, R.S.; McLellan, M.D.; Schmidt, H.; Kalicki-Veizer, J.; McMichael, J.F.; Fulton, L.L.; Dooling, D.J.; Ding, L.; Cancer Genome Atlas Network; et al. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 2012, 490, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandoth, C.; Schultz, N.; Cherniack, A.D.; Akbani, R.; Liu, Y.; Shen, H.; Robertson, A.G.; Pashtan, I.; Shen, R.; Benz, C.C.; et al. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature 2013, 497, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, D.; Berchuck, A.; Birrer, M.; Chien, J.; Cramer, D.W.; Dao, F.; Dhir, R.; Disaia, P.; Gabra, H.; Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network; et al. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature 2011, 474, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc-Durand, F.; Xian, L.C.W.; Tan, D.S.P. Targeting the immune microenvironment for ovarian cancer therapy. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1328651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Martín, A.; Sánchez-Lorenzo, L. Immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors in patients with ovarian cancer: Still promising? Cancer 2019, 125 (Suppl. S24), 4616–4622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, F.; Zhu, T.; Pan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, H.; Wang, X.; Zhao, J.; Li, P.; Xu, H.; Chen, H.; et al. Comprehensive genomic profiling of high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma from Chinese patients identifies co-occurring mutations in the Ras/Raf pathway with TP53. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 3928–3935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowtell, D.D.; Böhm, S.; Ahmed, A.A.; Aspuria, P.J.; Bast, R.C., Jr.; Beral, V.; Berek, J.S.; Birrer, M.J.; Blagden, S.; Calvert, H.; et al. Rethinking ovarian cancer II: Reducing mortality from high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2015, 15, 668–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wylie, B.; Macri, C.; Mintern, J.D.; Waithman, J.; Patton, T.; Hedges, J.; Broughton, S.E.; Harrison, A.; Mintern, N.A.; Tang, M.L.K.; et al. Dendritic Cells and Cancer: From Biology to Therapeutic Intervention. Cancers 2019, 11, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balan, S.; Saxena, M.; Bhardwaj, N. Dendritic cell subsets and locations. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2019, 348, 1–68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Broz, M.L.; Binnewies, M.; Boldajipour, B.; Nelson, A.E.; Pollack, J.L.; Erle, D.J.; Barczak, A.; Alvarado, M.D.; Rosenblum, M.D.; Mariathasan, S.; et al. Dissecting the tumor myeloid compartment reveals rare activating antigen-presenting cells critical for T cell immunity. Cancer Cell 2014, 26, 638–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binnewies, M.; Roberts, E.W.; Kersten, K.; Chan, V.; Fearon, D.F.; Merad, M.; Coussens, L.M.; Gabrilovich, D.I.; Ostrand-Rosenberg, S.; Hedrick, C.C.; et al. Understanding the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) for effective therapy. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K.L.; Caton, M.L.; Bogunovic, M.; Greter, M.; Grajkowska, L.T.; Ng, D.; Klinman, E.; Platt, A.M.; Artyomov, M.N.; Rajewsky, K.; et al. Notch2 receptor signaling controls functional differentiation of dendritic cells in the spleen and intestine. Immunity 2011, 35, 780–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.C.; Gudjonson, H.; Pritykin, Y.; Deep, D.; Lavallée, V.P.; Mendoza, A.; Chiou, J.; Varma, G.; Yao, E.; Gefen, M.; et al. Transcriptional Basis of Mouse and Human Dendritic Cell Heterogeneity. Cell 2019, 179, 846–863.e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisirak, V.; Faget, J.; Gobert, M.; Goutagny, N.; Vey, N.; Treilleux, I.; Renaudineau, S.; Habib, M.; Garnier, L.; Bendriss-Vermare, N.; et al. Impaired IFN-α production by plasmacytoid dendritic cells favors regulatory T-cell expansion that may contribute to breast cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 5188–5197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wculek, S.K.; Cueto, F.J.; Mujal, A.M.; Melero, I.; Krummel, M.F.; Sancho, D.; Sanz, E.; Gomez, M.J.; Fajardo, C.A.; Rouanne, M.; et al. Dendritic cells in cancer immunology and immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, B.; Leader, A.M.; Chen, S.T.; Tung, N.; Chang, C.; LeBerichel, J.; Chudnovskiy, A.; Maskenia, S.; Walker, L.; Finnigan, J.P.; et al. A conserved dendritic-cell regulatory program limits antitumour immunity. Nature 2020, 580, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blagih, J.; Zani, F.; Chakravarty, P.; Hennequart, M.; Pilley, S.; Hobor, S.; Booth, L.; Varghese, A.; Saha, J.; Minden, A.; et al. Cancer-Specific Loss of p53 Leads to a Modulation of Myeloid and T Cell Responses. Cell Rep. 2020, 30, 481–496.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hato, L.; Vizcay, A.; Eguren, I.; Pérez-Gracia, J.L.; Rodríguez, J.; Gallego Pérez-Larraya, J.; San Miguel, J.F.; Arana, E.; Melero, I.; Ponz-Sarvise, M.; et al. Dendritic Cells in Cancer Immunology and Immunotherapy. Cancers 2024, 16, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellrott, K.; Bailey, M.H.; Saksena, G.; Covington, K.R.; Kandoth, C.; Stewart, C.; Hess, J.; Ma, S.; Chiotti, K.E.; McLellan, M.D.; et al. Scalable Open Science Approach for Mutation Calling of Tumor Exomes Using Multiple Genomic Pipelines. Cell Syst. 2018, 6, 271–281.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A.C.; Korkut, A.; Kanchi, R.S.; Hegde, A.M.; Lenoir, W.; Liu, W.; Liu, Y.; Fan, H.; Shen, H.; Ravikumar, V.; et al. A Comprehensive Pan-Cancer Molecular Study of Gynecologic and Breast Cancers. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 690–705.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszkowska, K.A.; Piecuch, A.; Sady, M.; Gajewski, Z.; Flis, S.; Grzybowska-Szatkowska, L.; Szymczyk, A.; Grzybowska, M.; Dziuba, I.; Kornafel, J.; et al. Gain of Function (GOF) Mutant p53 in Cancer-Current Therapeutic Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, M.; Saha, S.; Bettke, J.; Nagar, R.; Parrales, A.; Iwakuma, T.; Van Saun, M.; Garcia, D.; Chanda, D.; Vyas, A.; et al. Mutant p53 suppresses innate immune signaling to promote tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell 2021, 39, 494–508.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finotello, F.; Mayer, C.; Plattner, C.; Laschober, G.; Rieder, D.; Hackl, H.; Trajanoski, Z.; Krogsdam, A.; Posch, W.; Schirmer, M.; et al. Molecular and pharmacological modulators of the tumor immune contexture revealed by deconvolution of RNA-seq data. Genome Med. 2019, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, G.; Finotello, F.; Petitprez, F.; Zhang, J.D.; Baumbach, J.; Fridman, W.H.; Höllerer, I.; List, M.; Aneichyk, T.; Ballesteros-Pena, A.; et al. Comprehensive evaluation of transcriptome-based cell-type quantification methods for immuno-oncology. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, i436–i445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marteau, V.; Nemati, N.; Handler, K.; Raju, D.; Kirchmair, A.; Rieder, D.; Nemethova, V.; Meier, C.; Leitner, J.; Pichler, V.; et al. Single-cell integration and multi-modal profiling reveals phenotypes and spatial organization of neutrophils in colorectal cancer. bioRxiv 2024, arXiv:2024.08.26.609563. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-García, I.; Uhlitz, F.; Ceglia, N.; Lim, J.L.P.; Wu, M.; Mohibullah, N.; Dey, K.K.; Nitzan, M.; Wyman, S.; Bhaduri, A.; et al. Ovarian cancer mutational processes drive site-specific immune evasion. Nature 2022, 612, 778–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hänzelmann, S.; Castelo, R.; Guinney, J. GSVA: Gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinform. 2013, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermi, W.; Soncini, M.; Melocchi, L.; Sozzani, S.; Facchetti, F.; Colombo, M.P.; Riboldi, E.; Prada, E.; Bosisio, D.; D’Amico, G.; et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells and cancer. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2011, 90, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labidi-Galy, S.I.; Treilleux, I.; Goddard-Leon, S.; Combes, J.D.; Blay, J.Y.; Ray-Coquard, I.; Caux, C. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells infiltrating ovarian cancer are associated with poor prognosis. Oncoimmunology 2012, 1, 380–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Färkkilä, A.; Gulhan, D.C.; Casado, J.; Jacobson, C.A.; Nguyen, H.; Kochupurakkal, B.; Lahtinen, L.; Andor, N.; Deng, X.; Ojasalo, M.; et al. Immunogenomic profiling determines responses to combined PARP and PD-1 inhibition in ovarian cancer. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, H.; Wang, W.; Qi, W.; Jin, W.; Xia, B.; Li, J.; Yang, F.; Chen, Y.; Huang, J.; Sun, L.; et al. Targeting DNA Repair Response Promotes Immunotherapy in Ovarian Cancer: Rationale and Clinical Application. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 661115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumacher, T.N.; Schreiber, R.D. Neoantigens in cancer immunotherapy. Science 2015, 348, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Wu, M.; Liu, Z. Dysregulation in IFN-γ signaling and response: The barricade to tumor immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1190333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVito, N.C.; Plebanek, M.P.; Theivanthiran, B.; Hanks, B.A.; Sen, S.K.; Smith, T.; Jones, K.; Bosenberg, M.; Conejo-Garcia, J.R.; Sanders, S.; et al. Role of Tumor-Mediated Dendritic Cell Tolerization in Immune Evasion. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiso, A.; Heinemann, A.; Kargl, J. Prostaglandin E2 in the Tumor Microenvironment, a Convoluted Affair Mediated by EP Receptors 2 and 4. Pharmacol. Rev. 2024, 76, 388–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsberry, W.N.; Meza-Perez, S.; Londoño, A.I.; Katre, A.A.; Mott, B.T.; Roane, B.M.; Bashir, A.; Yang, E.S.; Katre, A.; McDonald, J.; et al. Inhibiting WNT Ligand Production for Improved Immune Recognition in the Ovarian Tumor Microenvironment. Cancers 2020, 12, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, C.; Pierini-Malosse, C.; Rahmani, K.; Valente, M.; Collinet, N.; Bessou, G.; Goudot, C.; Simoni, Y.; Ramond, E.; Rufiange, A.; et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells are dispensable or detrimental in murine systemic or respiratory viral infections. Nat. Immunol. 2025, 26, 1962–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, E.; Yamada, M.; Nomura, S.; Iyoshi, S.; Mogi, K.; Uno, K.; Tanaka, Y.; Sato, H.; Fujita, M.; Kobayashi, T.; et al. Unraveling neutrophil diversity in ovarian cancer: Bridging clinical insights and basic research. Acad. Oncol. 2025, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Lawrence, T.; Liang, Y. The Role of Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells in Cancers. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 749190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, P.J.; Getz, G.; Stuart, J.M.; Korbel, J.O.; Stein, L.D.; Hudson, T.J.; Wheeler, D.A.; Korlach, J.; MacLean, A.; Zhang, X.; et al. Pan-cancer analysis of whole genomes. Nature 2020, 578, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlsen, L.; Zhang, S.; Tian, X.; De La Cruz, A.; George, A.; Arnoff, T.E.; Patel, R.; Lopez, S.; Ahmed, A.A.; Kwon, J.; et al. The role of p53 in anti-tumor immunity and response to immunotherapy. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2023, 10, 1148389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binnewies, M.; Mujal, A.M.; Pollack, J.L.; Combes, A.J.; Hardison, E.A.; Barry, K.C.; Li, N.; Wu, M.; Wang, L.; Krummel, M.F.; et al. Unleashing Type-2 Dendritic Cells to Drive Protective Antitumor CD4(+) T Cell Immunity. Cell 2019, 177, 556–571.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeneman, B.; Schreibelt, G.; Duiveman-de Boer, T.; Bos, K.; van Oorschot, T.; Pots, J.; van de Sande, A.; de Vries, I.J.M.; Meerding, J.; Hobo, W.; et al. NEOadjuvant Dendritic cell therapy added to first line standard of care in advanced epithelial Ovarian Cancer (NEODOC): Protocol of a first-in-human, exploratory, single-centre phase I/II trial in the Netherlands. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e102184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoadley, K.A.; Yau, C.; Hinoue, T.; Wolf, D.M.; Lazar, A.J.; Drill, E.; Shen, R.; Taylor, A.M.; Cherniack, A.D.; Thorsson, V.; et al. Cell-of-Origin Patterns Dominate the Molecular Classification of 10,000 Tumors from 33 Types of Cancer. Cell 2018, 173, 291–304.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lichtenberg, T.; Hoadley, K.A.; Poisson, L.M.; Lazar, A.J.; Cherniack, A.D.; Kovatich, A.J.; Benz, C.C.; Levine, D.A.; Lee, A.V.; et al. An Integrated TCGA Pan-Cancer Clinical Data Resource to Drive High-Quality Survival Outcome Analytics. Cell 2018, 173, 400–416.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, M.; Lunceford, J.; Nebozhyn, M.; Murphy, E.; Loboda, A.; Kaufman, D.R.; Albright, A.; Cheng, J.D.; Kang, S.P.; Shankaran, V.; et al. IFN-γ-related mRNA profile predicts clinical response to PD-1 blockade. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 2930–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberzon, A.; Birger, C.; Thorvaldsdóttir, H.; Ghandi, M.; Mesirov, J.P.; Tamayo, P.; Parker, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wong, C.; et al. The Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst. 2015, 1, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFS | OS | PFS | OS | ||||||

| HR [95%—CI] | p | HR [95%—CI] | p | HR [95%—CI] | p | HR [95%—CI] | p | ||

| TP53-mutated high-grade serous ovarian cancer | |||||||||

| Age | low vs. high | 1.31 [1–1.72] | 0.05 | 1.53 [1.13–2.07] | 0.006 | 1.69 [1.12–2.51] | 0.009 | 2.21 [1.42–3.44] | <0.001 |

| FIGO stage | I/II vs. III/IV | 2.02 [1.04–3.94] | 0.039 | 1.39 [0.65–2.97] | 0.397 | 1.09 [0.44–2.68] | 0.860 | 0.83 [0.30–2.29] | 0.715 |

| Residual disease | R0 vs. R1 | 0.87 [0.63–1.22] | 0.427 | 0.87 [0.61–1.26] | 0.464 | 0.88 [0.53–1.48] | 0.639 | 0.84 [0.47–1.51] | 0.554 |

| pDCs | low vs. high | 1.55 [1.05–2.27] | 0.027 | 1.43 [0.93–2.19] | 0.101 | 1.62 [1.09–2.40] | 0.017 | 1.66 [1.06–2.59] | 0.026 |

| TP53-Mutated High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage | pDC | |||

| Median | Range | p-Value | |||

| Variant type | |||||

| SNP | 129 | 80% | 3.011 | 2.696–3.332 | 0.717 |

| INS | 7 | 4% | 2.960 | 2.795–3.388 | |

| DEL | 26 | 16% | 3.006 | 2.761–3.659 | |

| Variant classification | |||||

| Missense | 91 | 56% | 3.040 | 2.761–3.356 | 0.161 |

| Nonsense | 19 | 12% | 2.929 | 2.620–3.336 | |

| Silent | 1 | 1% | - | - | |

| Splice site | 18 | 11% | 2.744 | 2.598–3.200 | |

| Frame shift indel | 28 | 17% | 2.970 | 2.760–3.377 | |

| Inframe indel | 5 | 3% | 3.744 | 2.879–3.882 | |

| 3’ UTR | 0 | 0% | - | - | |

| Intron | 0 | 0% | - | - | |

| Function | |||||

| GOF | 21 | 13% | 3.022 | 2.961–3.200 | 0.565 |

| LOF | 141 | 87% | 2.975 | 2.696–3.404 | |

| Localization (domains) | |||||

| Transactivation TAD1 | 3 | 2% | 3.752 | - | 0.209 |

| Transactivation TAD2 | 3 | 2% | 3.473 | - | |

| SH3-like/Pro-rich | 1 | 1% | - | - | |

| NA; N-term | 1 | 1% | - | - | |

| DNA binding | 136 | 84% | 3.023 | 2.749–3.389 | |

| NA; C-term | 6 | 4% | 2.792 | 2.520–2.955 | |

| NLS | 4 | 2% | 3.024 | 2.937–3.544 | |

| Tetramerization | 8 | 5% | 2.739 | 2.510–3.112 | |

| Regulation | 0 | 0% | - | - | |

| NA | 0 | 0% | - | - | |

| TP53 aberration in the relevant region described by Ghosh et al. [38] | |||||

| (one patient with a silent mutation was excluded) | |||||

| No, other region | 122 | 76% | 3.050 | 2.775–3.406 | 0.015 |

| Yes | 39 | 24% | 2.887 | 2.608–3.247 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Steger, K.; Fiegl, H.; Rungger, K.; Leitner, K.; Tsibulak, I.; Feroz, B.; Ebner, C.; Marth, C.; Hackl, H.; Zeimet, A.G. The Role of Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells in the Immune Contexture of TP53-Mutated High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer. Cancers 2025, 17, 3877. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233877

Steger K, Fiegl H, Rungger K, Leitner K, Tsibulak I, Feroz B, Ebner C, Marth C, Hackl H, Zeimet AG. The Role of Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells in the Immune Contexture of TP53-Mutated High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3877. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233877

Chicago/Turabian StyleSteger, Katharina, Heidelinde Fiegl, Katja Rungger, Katharina Leitner, Irina Tsibulak, Barin Feroz, Christoph Ebner, Christian Marth, Hubert Hackl, and Alain Gustave Zeimet. 2025. "The Role of Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells in the Immune Contexture of TP53-Mutated High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3877. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233877

APA StyleSteger, K., Fiegl, H., Rungger, K., Leitner, K., Tsibulak, I., Feroz, B., Ebner, C., Marth, C., Hackl, H., & Zeimet, A. G. (2025). The Role of Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells in the Immune Contexture of TP53-Mutated High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer. Cancers, 17(23), 3877. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233877