Genitourinary Microbiome and Volatilome: A Pilot Study in Patients with Prostatic Adenocarcinoma Submitted to Radical Prostatectomy

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Patient Selection Criteria

2.3. Clinical Procedures and Follow-Up

2.4. Specimen Collection

2.5. DNA Extraction from Urine and Prostate Tissue

2.6. Detection and Quantification of HPyVs DNA

2.7. Sexually Transmitted Pathogen Detection

2.8. 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing, Processing, and Metagenomic Analysis

2.9. Urine Metabolomics HS-SPME/GC-MS Analysis

2.10. Data Pre-Processing

2.11. R-Based Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Detection of HPyVs in Urine and Prostatic Tissue from PC Patients

3.3. Detection of HPyVs in Urine from BPH Controls

3.4. HPyVs Coinfection Patterns in PC Patients

3.5. Detection of Sexually Transmitted Pathogens in Urine and Prostate Tissue

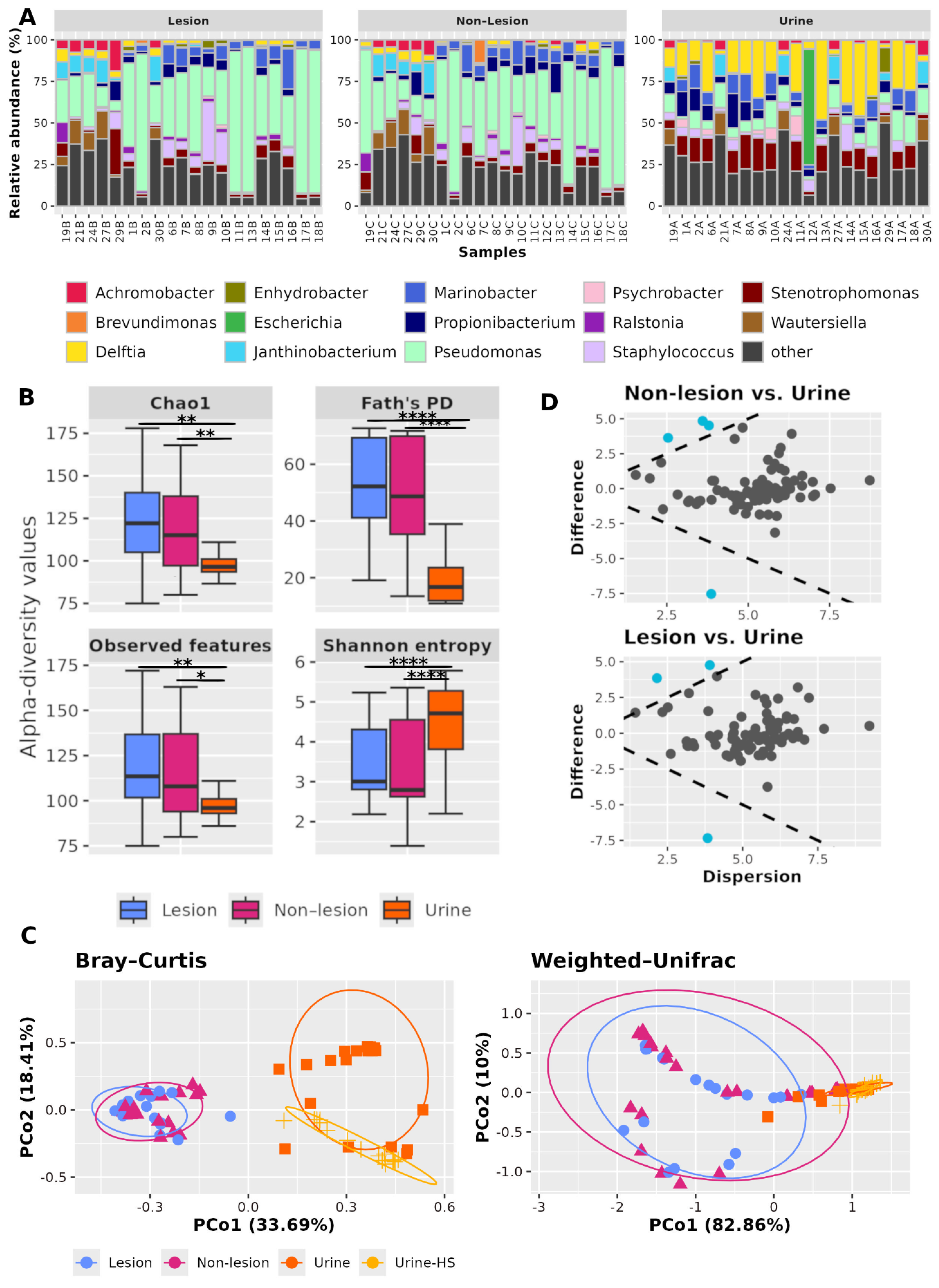

3.6. Sequencing and Bioinformatics Analysis

3.7. Comparisons Between Lesional and Non-Lesional Prostate Tissue Microbiota

3.8. Comparisons of Microbiota in Prostate Tissue and Catheterized Urine

3.9. Comparisons of Urine Microbiota in PC and BPH Patients

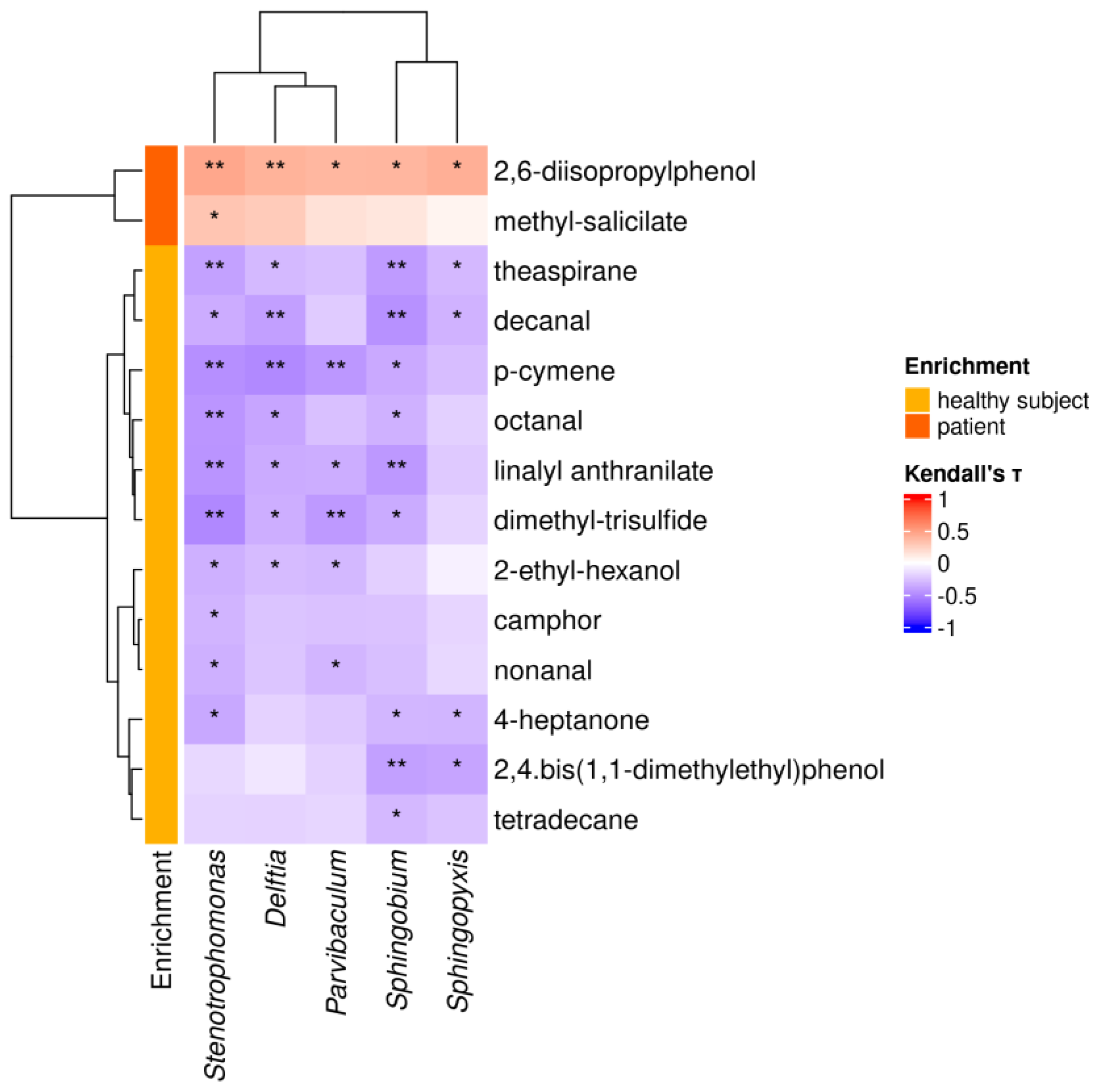

3.10. HS-SPME/GC-MS Analysis of the Urine VOM Fraction

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BPH | benign prostatic hyperplasia |

| VOMs | volatile organic metabolites |

| PC | Prostate cancer |

| HPV | Human Papillomavirus |

| EBV | Epstein–Barr virus |

| HHVs | human herpesviruses |

| CMV | Cytomegalovirus |

| KSHV | Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus |

| HPyVs | Human Polyomaviruses |

| MCPyV | Merkel cell polyomavirus |

| JCPyV | JC polyomavirus |

| BKPyV | BK polyomavirus |

| RP | radical prostatectomy |

| ST | sexually transmitted |

| PSA | prostate-specific antigen |

| mpMRI | multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging |

| EAU | European Association of Urology |

| PET-CT | positron emission tomography-computed tomography |

| RP | Robotic-assisted laparoscopic |

| ISUP | International Society of Urological Pathology |

| PSMA | Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen |

| qPCR | Quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| LTAg | Large T Antigen |

| VP1 | Viral Protein 1 |

| sTAg | small T antigen |

| GC | gas chromatograph/ chromatography |

| DAA | Differential abundance analysis |

| EAU | risk classification, tumor staging |

| ISUP | grade, surgical margins, and biochemical recurrence |

| OSAS | Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

References

- Prostate Cancer Burden in EU-27. Available online: https://ecis.jrc.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2023-12/prostate_cancer_En-Nov_2021.pdf (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- World Cancer Research Fund. Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/cancer-trends/prostate-cancer-statistics (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Cooperberg, M.R.; Carroll, P.R. Trends in Management for Patients With Localized Prostate Cancer, 1990–2013. JAMA 2015, 314, 80–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhao, D.; Spring, D.J.; DePinho, R.A. Genetics and Biology of Prostate Cancer. Genes. Dev. 2018, 32, 1105–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.J.; Autio, K.A.; Roach, M., 3rd; Scher, H.I. High-Risk Prostate Cancer-Classification and Therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 11, 308–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, M.J.; Simmons, L.H. Prevention of Prostate Cancer Morbidity and Mortality: Primary Prevention and Early Detection. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 101, 787–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollica, V.; Rizzo, A.; Massari, F. The Pivotal Role of TMPRSS2 in Coronavirus Disease 2019 and Prostate Cancer. Future Oncol. 2020, 16, 2029–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, E.; Coulter, J.B.; Guzman, W.; Ozbek, B.; Hess, M.M.; Mummert, L.; Ernst, S.E.; Maynard, J.P.; Meeker, A.K.; Heaphy, C.M.; et al. Oncogenic Gene Fusions in Nonneoplastic Precursors as Evidence That Bacterial Infection Can Initiate Prostate Cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2018976118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, J.S.; Glenn, W.K. Multiple Pathogens and Prostate Cancer. Infect. Agent. Cancer 2022, 17, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abumsimir, B.; Almahasneh, I.; Kasmi, Y.; Hammou, R.A.; Ennaji, M.M. Chapter 15—Prostate Cancer and Viral Infections: Epidemiological and Clinical Indications. In Oncogenic Viruses Volume 1: Fundamentals of Oncoviruses 2023; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; pp. 263–272.

- Tsydenova, I.A.; Ibragimova, M.K.; Tsyganov, M.M.; Litviakov, N.V. Human Papillomavirus and Prostate Cancer: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Wang, Z.; Qian, Y.; Chen, H.; Shi, Y.; Huang, J.; Guo, X.; Yu, M.; Yu, Y. Unveiling the Impact of Epstein-Barr Virus on the Risk of Prostate Cancer: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Nutr. Cancer 2025, 77, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorova, E.; Kavrakova, A.; Derimachkovski, G.; Georgieva, B.; Odzhakov, F.; Bachurska, S.; Terziev, I.; Boyadzhieva, M.-E.; Valkov, T.; Popov, E.; et al. Human Herpes Virus Genotype and Immunological Gene Expression Profile in Prostate Cancer with Prominent Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano, A.; Kalantari, M.; Simoneau, A.; Jensen, J.L.; Villarreal, L.P. Detection of Human Polyomaviruses and Papillomaviruses in Prostatic Tissue Reveals the Prostate as a Habitat for Multiple Viral Infections. Prostate 2002, 53, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Tung, C.; Chao, C.; Jou, Y.; Huang, S.; Meng, M.; Chang, D.; Chen, P. The Differential Presence of Human Polyomaviruses, JCPyV and BKPyV, in Prostate Cancer and Benign Prostate Hypertrophy Tissues. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Shuda, M.; Chang, Y.; Moore, P.S. Clonal Integration of a Polyomavirus in Human Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Science 2008, 319, 1096–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, J.C.M.; Monezi, T.A.; Amorim, A.T.; Lino, V.; Paladino, A.; Boccardo, E. Human Polyomaviruses and Cancer: An Overview. Clinics 2018, 73, e558s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzivino, E.; Rodio, D.M.; Mischitelli, M.; Bellizzi, A.; Sciarra, A.; Salciccia, S.; Gentile, V.; Pietropaolo, V. High Frequency of JCV DNA Detection in Prostate Cancer Tissues. Cancer Genom. Proteom. 2015, 12, 189–200. [Google Scholar]

- Delbue, S.; Matei, D.-V.; Carloni, C.; Pecchenini, V.; Carluccio, S.; Villani, S.; Tringali, V.; Brescia, A.; Ferrante, P. Evidence Supporting the Association of Polyomavirus BK Genome with Prostate Cancer. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2013, 202, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balis, V.; Sourvinos, G.; Soulitzis, N.; Giannikaki, E.; Sofras, F.; Spandidos, D.A. Prevalence of BK Virus and Human Papillomavirus in Human Prostate Cancer. Int. J. Biol. Markers 2007, 22, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Wojno, K.; Imperiale, M.J. BK Virus as a Cofactor in the Etiology of Prostate Cancer in Its Early Stages. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 2705–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, G.; Anzivino, E.; Fioriti, D.; Mischitelli, M.; Bellizzi, A.; Giordano, A.; Autran-Gomez, A.; Di Monaco, F.; Di Silverio, F.; Sale, P.; et al. p53 Gene Mutational Rate, Gleason Score, and BK Virus Infection in Prostate Adenocarcinoma: Is There a Correlation? J. Med. Virol. 2008, 80, 2100–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csoboz, B.; Rasheed, K.; Sveinbjørnsson, B.; Moens, U. Merkel Cell Polyomavirus and Non-Merkel Cell Carcinomas: Guilty or Circumstantial Evidence? APMIS 2020, 128, 104–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluemn, E.G.; Paulson, K.G.; Higgins, E.E.; Sun, Y.; Nghiem, P.; Nelson, P.S. Merkel Cell Polyomavirus Is Not Detected in Prostate Cancers, Surrounding Stroma, or Benign Prostate Controls. J. Clin. Virol. 2009, 44, 164–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massari, F.; Mollica, V.; Di Nunno, V.; Gatto, L.; Santoni, M.; Scarpelli, M.; Cimadamore, A.; Lopez-Beltran, A.; Cheng, L.; Battelli, N.; et al. The Human Microbiota and Prostate Cancer: Friend or Foe? Cancers 2019, 11, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, R.M.; Pereira-Marques, J.; Pinto-Ribeiro, I.; Costa, J.L.; Carneiro, F.; Machado, J.C.; Figueiredo, C. Gastric Microbial Community Profiling Reveals a Dysbiotic Cancer-Associated Microbiota. Gut 2018, 67, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocáriz-Díez, M.; Cruellas, M.; Gascón, M.; Lastra, R.; Martínez-Lostao, L.; Ramírez-Labrada, A.; Paño, J.R.; Sesma, A.; Torres, I.; Yubero, A.; et al. Microbiota and Lung Cancer. Opportunities and Challenges for Improving Immunotherapy Efficacy. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 568939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visconti, A.; Le Roy, C.I.; Rosa, F.; Rossi, N.; Martin, T.C.; Mohney, R.P.; Li, W.; de Rinaldis, E.; Bell, J.T.; Venter, J.C.; et al. Interplay between the Human Gut Microbiome and Host Metabolism. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.R.; Pinto, J.; Amaro, F.; Bastos, M.d.L.; Carvalho, M.; Guedes de Pinho, P. Advances and Perspectives in Prostate Cancer Biomarker Discovery in the Last 5 Years through Tissue and Urine Metabolomics. Metabolites 2021, 11, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinges, S.S.; Hohm, A.; Vandergrift, L.A.; Nowak, J.; Habbel, P.; Kaltashov, I.A.; Cheng, L.L. Cancer Metabolomic Markers in Urine: Evidence, Techniques and Recommendations. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2019, 16, 339–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Nath, K.; Lal, H.; Gupta, A. Noninvasive Urine Metabolomics of Prostate Cancer and Its Therapeutic Approaches: A Current Scenario and Future Perspective. Expert. Rev. Proteom. 2021, 18, 995–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchesi, J.R.; Adams, D.H.; Fava, F.; Hermes, G.D.A.; Hirschfield, G.M.; Hold, G.; Quraishi, M.N.; Kinross, J.; Smidt, H.; Tuohy, K.M.; et al. The Gut Microbiota and Host Health: A New Clinical Frontier. Gut 2016, 65, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Li, Q.; Li, P.; Chen, X.; Xiang, L.; Bi, L.; Zhu, J.; Huang, X.; Cui, B.; Zhang, F. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation: A Promising Treatment for Radiation Enteritis? Radiother. Oncol. 2020, 143, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Leenders, G.J.L.H.; van der Kwast, T.H.; Grignon, D.J.; Evans, A.J.; Kristiansen, G.; Kweldam, C.F.; Litjens, G.; McKenney, J.K.; Melamed, J.; Mottet, N.; et al. The 2019 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consensus Conference on Grading of Prostatic Carcinoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2020, 44, e87–e99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbue, S.; Franciotta, D.; Giannella, S.; Dolci, M.; Signorini, L.; Ticozzi, R.; D’Alessandro, S.; Campisciano, G.; Comar, M.; Ferrante, P.; et al. Human Polyomaviruses in the Cerebrospinal Fluid of Neurological Patients. Microorganisms 2019, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passerini, S.; Babini, G.; Merenda, E.; Carletti, R.; Scribano, D.; Rosa, L.; Conte, A.L.; Moens, U.; Ottolenghi, L.; Romeo, U.; et al. Merkel Cell Polyomavirus in the Context of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Oral Potentially Malignant Disorders. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. Search and Clustering Orders of Magnitude Faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 2460–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M. Cutadapt Removes Adapter Sequences from High-Throughput Sequencing Reads. EMBnet J. 2011, 17, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, Interactive, Scalable and Extensible Microbiome Data Science Using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-Resolution Sample Inference from Illumina Amplicon Data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, G.M.; Maffei, V.J.; Zaneveld, J.R.; Yurgel, S.N.; Brown, J.R.; Taylor, C.M.; Huttenhower, C.; Langille, M.G.I. PICRUSt2 for Prediction of Metagenome Functions. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 685–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, M.; Carvalho, M.; Henrique, R.; Jerónimo, C.; Moreira, N.; de Lourdes Bastos, M.; de Pinho, P.G. Analysis of Volatile Human Urinary Metabolome by Solid-Phase Microextraction in Combination with Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry for Biomarker Discovery: Application in a Pilot Study to Discriminate Patients with Renal Cell Carcinoma. Eur. J. Cancer 2014, 50, 1993–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tautenhahn, R.; Patti, G.J.; Rinehart, D.; Siuzdak, G. XCMS Online: A Web-Based Platform to Process Untargeted Metabolomic Data. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 5035–5039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALDEx2. Available online: http://bioconductor.org/packages/ALDEx2/ (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Cavarretta, I.; Ferrarese, R.; Cazzaniga, W.; Saita, D.; Lucianò, R.; Ceresola, E.R.; Locatelli, I.; Visconti, L.; Lavorgna, G.; Briganti, A.; et al. The Microbiome of the Prostate Tumor Microenvironment. Eur. Urol. 2017, 72, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Ramnarine, V.R.; Bell, R.; Volik, S.; Davicioni, E.; Hayes, V.M.; Ren, S.; Collins, C.C. Metagenomic and Metatranscriptomic Analysis of Human Prostate Microbiota from Patients with Prostate Cancer. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, M.F.M.; Pina-Vaz, T.; Fernandes, Â.R.; Miranda, I.M.; Silva, C.M.; Rodrigues, A.G.; Lisboa, C. Microbiota of Urine, Glans and Prostate Biopsies in Patients with Prostate Cancer Reveals a Dysbiosis in the Genitourinary System. Cancers 2023, 15, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Antonio, D.L.; Marchetti, S.; Pignatelli, P.; Piattelli, A.; Curia, M.C. The Oncobiome in Gastroenteric and Genitourinary Cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Li, Y.; Zhou, L.; Li, H.; Wan, T.; Tang, J.; Zhou, L.; Xie, H.; Wang, L. Microbiome Analysis Reveals the Inducing Effect of on Prostatic Hyperplasia via Activating NF-κB Signalling. Virulence 2024, 15, 2313410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyrich, L.S.; Farrer, A.G.; Eisenhofer, R.; Arriola, L.A.; Young, J.; Selway, C.A.; Handsley-Davis, M.; Adler, C.J.; Breen, J.; Cooper, A. Laboratory contamination over time during low-biomass sample analysis. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2019, 19, 982–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katongole, P.; Sande, O.J.; Joloba, M.; Reynolds, S.J.; Niyonzima, N. The Human Microbiome and Its Link in Prostate Cancer Risk and Pathogenesis. Infect. Agent. Cancer 2020, 15, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, K.; Takezawa, K.; Tsujimura, G.; Imanaka, T.; Kuribayashi, S.; Ueda, N.; Hatano, K.; Fukuhara, S.; Kiuchi, H.; Fujita, K.; et al. Localization and Potential Role of Prostate Microbiota. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 1048319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yow, M.A.; Tabrizi, S.N.; Severi, G.; Bolton, D.M.; Pedersen, J.; Australian Prostate Cancer BioResource; Giles, G.G.; Southey, M.C. Characterisation of Microbial Communities within Aggressive Prostate Cancer Tissues. Infect. Agent. Cancer 2017, 12, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuchi, R.; Goto, T.; Hirotsu, Y.; Otake, S.; Oyama, T.; Amemiya, K.; Mochizuki, H.; Omata, M. Streptococcus australis and Ralstonia pickettii as Major Microbiota in Mesotheliomas. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, K.; Matsushita, M.; De Velasco, M.A.; Hatano, K.; Minami, T.; Nonomura, N.; Uemura, H. The Gut-Prostate Axis: A New Perspective of Prostate Cancer Biology through the Gut Microbiome. Cancers 2023, 15, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatheru Waigi, M.; Sun, K.; Gao, Y. Sphingomonads in Microbe-Assisted Phytoremediation: Tackling Soil Pollution. Trends Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 883–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coradduzza, D.; Sanna, A.; Di Lorenzo, B.; Congiargiu, A.; Marra, S.; Cossu, M.; Tedde, A.; De Miglio, M.R.; Zinellu, A.; Mangoni, A.A.; et al. Associations between Plasma and Urinary Heavy Metal Concentrations and the Risk of Prostate Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anchidin-Norocel, L.; Iatcu, O.C.; Lobiuc, A.; Covasa, M. Heavy Metal-Gut Microbiota Interactions: Probiotics Modulation and Biosensors Detection. Biosensors 2025, 15, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalid, T.; Aggio, R.; White, P.; De Lacy Costello, B.; Persad, R.; Al-Kateb, H.; Jones, P.; Probert, C.S.; Ratcliffe, N. Urinary Volatile Organic Compounds for the Detection of Prostate Cancer. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccio, G.; Berenguer, C.V.; Perestrelo, R.; Pereira, F.; Berenguer, P.; Ornelas, C.P.; Sousa, A.C.; Vital, J.A.; Pinto, M.D.C.; Pereira, J.A.M.; et al. Differences in the Volatilomic Urinary Biosignature of Prostate Cancer Patients as a Feasibility Study for the Detection of Potential Biomarkers. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 4904–4921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, J.; Green, K.; Lazarowicz, H.; Cornford, P.; Probert, C. Analysis of Urinary Volatile Organic Compounds for Prostate Cancer Diagnosis: A Systematic Review. BJUI Compass 2024, 5, 822–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.R.; Pinto, J.; Azevedo, A.I.; Barros-Silva, D.; Jerónimo, C.; Henrique, R.; de Lourdes Bastos, M.; Guedes de Pinho, P.; Carvalho, M. Identification of a Biomarker Panel for Improvement of Prostate Cancer Diagnosis by Volatile Metabolic Profiling of Urine. Br. J. Cancer 2019, 121, 857–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenguer, C.V.; Pereira, F.; Pereira, J.A.M.; Câmara, J.S. Volatilomics: An Emerging and Promising Avenue for the Detection of Potential Prostate Cancer Biomarkers. Cancers 2022, 14, 3982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; De Melo, J.; Cutz, J.-C.; Aziz, T.; Tang, D. Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 3A1 Associates with Prostate Tumorigenesis. Br. J. Cancer 2014, 110, 2593–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, J.; Li, S.; Liu, S.; Zhang, L. Aldehyde Dehydrogenase in Solid Tumors and Other Diseases: Potential Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets. MedComm 2023, 4, e195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomono, S.; Miyoshi, N.; Ohshima, H. Comprehensive Analysis of the Lipophilic Reactive Carbonyls Present in Biological Specimens by LC/ESI-MS/MS. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2015, 988, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goertzen, A.; Kidane, B.; Ahmed, N.; Aliani, M. Potential Urinary Volatile Organic Compounds as Screening Markers in Cancer—A Review. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1448760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S.; Yoon, J.-S.; Song, M.; Shin, C.-Y.; Chung, H.S.; Ryu, J.-C. Gene Expression Profiling of Low Dose Exposure of Saturated Aliphatic Aldehydes in A549 Human Alveolar Epithelial Cells. Toxicol. Environ. Health Sci. 2012, 4, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbas, K.; Zapała, P.; Zapała, Ł.; Radziszewski, P. The Role of Microbial Factors in Prostate Cancer Development-An Up-to-Date Review. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janfaza, S.; Khorsand, B.; Nikkhah, M.; Zahiri, J. Digging Deeper into Volatile Organic Compounds Associated with Cancer. Biol. Methods Protoc. 2019, 4, bpz014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccio, G.; Baroni, S.; Urbani, A.; Greco, V. Mapping of Urinary Volatile Organic Compounds by a Rapid Analytical Method Using Gas Chromatography Coupled to Ion Mobility Spectrometry (GC-IMS). Metabolites 2022, 12, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Fan, Y.; Zeng, S.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, L.; Zhao, L.; Gao, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y. Volatile Organic Compounds for Early Detection of Prostate Cancer from Urine. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balahbib, A.; El Omari, N.; Hachlafi, N.E.; Lakhdar, F.; El Menyiy, N.; Salhi, N.; Mrabti, H.N.; Bakrim, S.; Zengin, G.; Bouyahya, A. Health Beneficial and Pharmacological Properties of P-Cymene. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2021, 153, 112259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokizane, T.; Shiina, H.; Igawa, M.; Enokida, H.; Urakami, S.; Kawakami, T.; Ogishima, T.; Okino, S.T.; Li, L.-C.; Tanaka, Y.; et al. Cytochrome P450 1B1 Is Overexpressed and Regulated by Hypomethylation in Prostate Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005, 11, 5793–5801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarnoutse, R.; Ziemons, J.; Penders, J.; Rensen, S.S.; de Vos-Geelen, J.; Smidt, M.L. The Clinical Link between Human Intestinal Microbiota and Systemic Cancer Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; He, J.; Yin, L.; Zhou, J.; Lian, J.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, J.; Wang, G.; Li, X. Matrix Metalloproteinases Targeting in Prostate Cancer. Urol. Oncol. 2024, 42, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Gao, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, F.; Li, C.; Ying, C. Characterization of Vaginal Microbiota in Chinese Women with Cervical Squamous Intra-Epithelial Neoplasia. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2020, 30, 1500–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Gnanasekar, A.; Lee, A.; Li, W.T.; Haas, M.; Wang-Rodriguez, J.; Chang, E.Y.; Rajasekaran, M.; Ongkeko, W.M. Influence of Intratumor Microbiome on Clinical Outcome and Immune Processes in Prostate Cancer. Cancers 2020, 12, 2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Leng, Q.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, J. P-Cymene Prevent High-Fat Diet-Associated Colorectal Cancer by Improving the Structure of Intestinal Flora. J. Cancer 2021, 12, 4355–4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessione, E. Lactic Acid Bacteria Contribution to Gut Microbiota Complexity: Lights and Shadows. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2012, 2, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan, A.; van Sinderen, D. Bifidobacteria and Their Role as Members of the Human Gut Microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, J.; Miller, G.; Li, X.; Saxena, D. Virome and Bacteriome: Two Sides of the Same Coin. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2019, 37, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergh, J.; Marklund, I.; Gustavsson, C.; Wiklund, F.; Grönberg, H.; Allard, A.; Alexeyev, O.; Elgh, F. No Link between Viral Findings in the Prostate and Subsequent Cancer Development. Br. J. Cancer 2007, 96, 137–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demey, B.; Aubry, A.; Descamps, V.; Morel, V.; Le, M.H.H.; Presne, C.; Brazier, F.; Helle, F.; Brochot, E. Molecular Epidemiology and Risk Factors Associated with BK and JC Polyomavirus Urinary Shedding after Kidney Allograft. J. Med. Virol. 2024, 96, e29742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safwat, A.S.; Hasanain, A.; Shahat, A.; AbdelRazek, M.; Orabi, H.; Abdul Hamid, S.K.; Nafee, A.; Bakkar, S.; Sayed, M. Cholecalciferol for the Prophylaxis against Recurrent Urinary Tract Infection among Patients with Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: A Randomized, Comparative Study. World J. Urol. 2019, 37, 1347–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciotti, M.; Prezioso, C.; Pietropaolo, V. An Overview on Human Polyomaviruses Biology and Related Diseases. Future Virol. 2019, 14, 487–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamminga, S. Polyomaviruses in Blood Donors: Detection, Prevalence and Blood Safety. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

| A. Clinical Comparison Between PC Patients and BPH Controls | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | PC Group (n = 21) | BPH Group (n = 17) | p-Value |

| Age (years) | 65.50 ± 5.98 (67.0; 55–73) | 64.70 ± 4.25 (64.0; 55–72) | 0.6334 |

| Weight (kg) | 81.70 ± 16.18 (80.0; 65–110) | 84.30 ± 12.35 (82.0; 75–110) | 0.5779 |

| Height (m) | 1.74 ± 0.06 (1.73; 1.65–1.86) | 1.76 ± 0.05 (1.74; 1.68–1.85) | 0.2699 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.90 ± 4.56 (26.64; 21.95–40.47) | 26.30 ± 3.84 (26.40; 21.45–40.25) | 0.6624 |

| Smoking status | Yes: 5 (23.8%) No: 12 (57.1%) Ex-smoker: 4 (19.1%) | Yes: 4 (23.5%) No: 10 (58.8%) Ex-smoker: 3 (17.6%) | 0.9926 |

| Family history of PC | Yes: 3 (14.3%) No: 18 (85.7%) | Yes: 2 (11.8%) No: 15 (88.2%) | 0.8192 |

| Family history of other cancers | Yes: 10 (47.6%) No: 11 (52.4%) | Yes: 8 (47.0%) No: 9 (53.0%) | 0.9726 |

| Comorbidities | Hypertension: 16 (76.2%) Dyslipidemia: 5 (23.8%) Diabetes mellitus II: 1 (4.8%) OSAS: 1 (4.8%) COPD: 1 (4.8%) Allergic asthma: 2 (9.5%) | Hypertension:15 (88.2%) Dyslipidemia: 4 (23.5%) Diabetes mellitus II: 4 (23.5%) OSAS: 0 (0%) COPD: 0 (0%) Allergic asthma: 0 (0%) | 0.3409 0.9839 0.0888 0.3619 0.3619 0.1911 |

| Prostate volume (cc) | 52.23 ± 24.20 (51.0;: 18.4–113.0) | 77.42 ± 21.35 (80.0; 55.0–120.0) | 0.0016 * |

| Total PSA (ng/mL) | 8.10 ± 4.32 (6.80; 3.8–17.0) | 4.24 ± 3.12 (4.80; 2.70–8.0.) | 0.0029 * |

| B. Pathological characteristics of PC group | |||

| Characteristic | Distribution (n = 21) | ||

| EAU Risk Classification | Low: 3 (14.3%) Intermediate: 17 (80.9%) High: 1 (4.8%) | ||

| Pathologic stage | pT2: 12 (57.1%) pT3a: 8 (38.1%) pT3b: 1 (4.8%) | ||

| ISUP Grade (at surgery) | Grade 1: 3 (14.3%) Grade 2: 14 (66.7%) Grade 3: 4 (19.0%) Grade 4: 0 (0%) | ||

| Surgical margins | Negative (R0): 14 (66.7%) Positive (R1): 7 (33.3%) | ||

| Biochemical progression | No: 18 (85.7%)—PSA: 0.03 ± 0.01 (0.04; 0.01–0.05) Yes: 3 (14.3%)—PSA: 0.47 ± 0.12 (0.5; 0.4–0.6) | ||

| Urine | Non-Lesional Samples | Lesional Samples | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Viral Load (Copies/mL), Median (CI 95%) | n (%) | Viral Load (Copies/mL), Median (CI 95%) | n (%) | Viral Load (Copies/mL), Median (CI 95%) | |

| JCPyV | 13/21 (61.9%) | 8.7 × 106 (2.25 × 105–1.5 × 106) | 4/21 (19%) | 1.38 × 103 (1.4 × 102–3.5 × 103) | 2/21 (9.5%) | 4.65 × 102 (2.5 × 102–6.8 × 102) |

| BKPyV | 12/21 (57.1%) | 1.33 × 105 (3.2 × 104–2.4 × 105) | 7/21 (33.3%) | 1.2 × 102 (9 × 10–2 × 102) | 2/21 (9.5%) | 8.5 × 10 (8 × 10–9 × 10) |

| MCPyV | - | - | 1/21 (4.8%) | 1 × 102 | 2/21 (9.5%) | 1.16 × 102 (1.1 × 102–1.2 × 102) |

| Metabolite Tag | IUPAC or Common Name | Class | Enrichment in PC Patients a | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2,6-diisopropylphenol | Alcohol | ↑ | <0.0001 |

| 4 | methyl-salicylate | Other | ↑ | <0.0001 |

| 27 | octanal | Aldehyde | ↓ | <0.0001 |

| 34 | p-cymene | Terpene | ↓ | <0.0001 |

| 31 | decanal | Aldehyde | ↓ | 0.0003 |

| 22 | camphor | c-Ketone | ↓ | 0.0004 |

| 9 | nonanal | Aldehyde | ↓ | 0.001 |

| 10 | 2,4.bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)phenol | Alcohol | ↓ | 0.001 |

| 6 | 4-heptanone | Ketone | ↓ | 0.002 |

| 21 | theaspirane | Tetrahydrofurane | ↓ | 0.002 |

| 18 | 2-ethyl-hexanol | Alcohol | ↓ | 0.012 |

| 33 | dimethyl-trisulfide | Sulfide | ↓ | 0.031 |

| 20 | tetradecane | Alkane | ↓ | 0.034 |

| 39 | pentadecane | Alkane | ↓ | 0.037 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Musleh, L.; Passerini, S.; Brunetti, F.; Maurizi, L.; Bevilacqua, G.; Santodirocco, L.; Sciarra, B.; Moriconi, M.; Fraschetti, C.; Filippi, A.; et al. Genitourinary Microbiome and Volatilome: A Pilot Study in Patients with Prostatic Adenocarcinoma Submitted to Radical Prostatectomy. Cancers 2025, 17, 3841. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233841

Musleh L, Passerini S, Brunetti F, Maurizi L, Bevilacqua G, Santodirocco L, Sciarra B, Moriconi M, Fraschetti C, Filippi A, et al. Genitourinary Microbiome and Volatilome: A Pilot Study in Patients with Prostatic Adenocarcinoma Submitted to Radical Prostatectomy. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3841. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233841

Chicago/Turabian StyleMusleh, Layla, Sara Passerini, Francesca Brunetti, Linda Maurizi, Giulio Bevilacqua, Lorenzo Santodirocco, Beatrice Sciarra, Martina Moriconi, Caterina Fraschetti, Antonello Filippi, and et al. 2025. "Genitourinary Microbiome and Volatilome: A Pilot Study in Patients with Prostatic Adenocarcinoma Submitted to Radical Prostatectomy" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3841. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233841

APA StyleMusleh, L., Passerini, S., Brunetti, F., Maurizi, L., Bevilacqua, G., Santodirocco, L., Sciarra, B., Moriconi, M., Fraschetti, C., Filippi, A., Conte, M. P., Pietropaolo, V., Di Pietro, M., Filardo, S., Sciarra, A., & Longhi, C. (2025). Genitourinary Microbiome and Volatilome: A Pilot Study in Patients with Prostatic Adenocarcinoma Submitted to Radical Prostatectomy. Cancers, 17(23), 3841. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233841