New Treatment Options for Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Narrative Review

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

- −

- To highlight recent progress in diagnostic and treatment technologies, including advancements in digital technologies;

- −

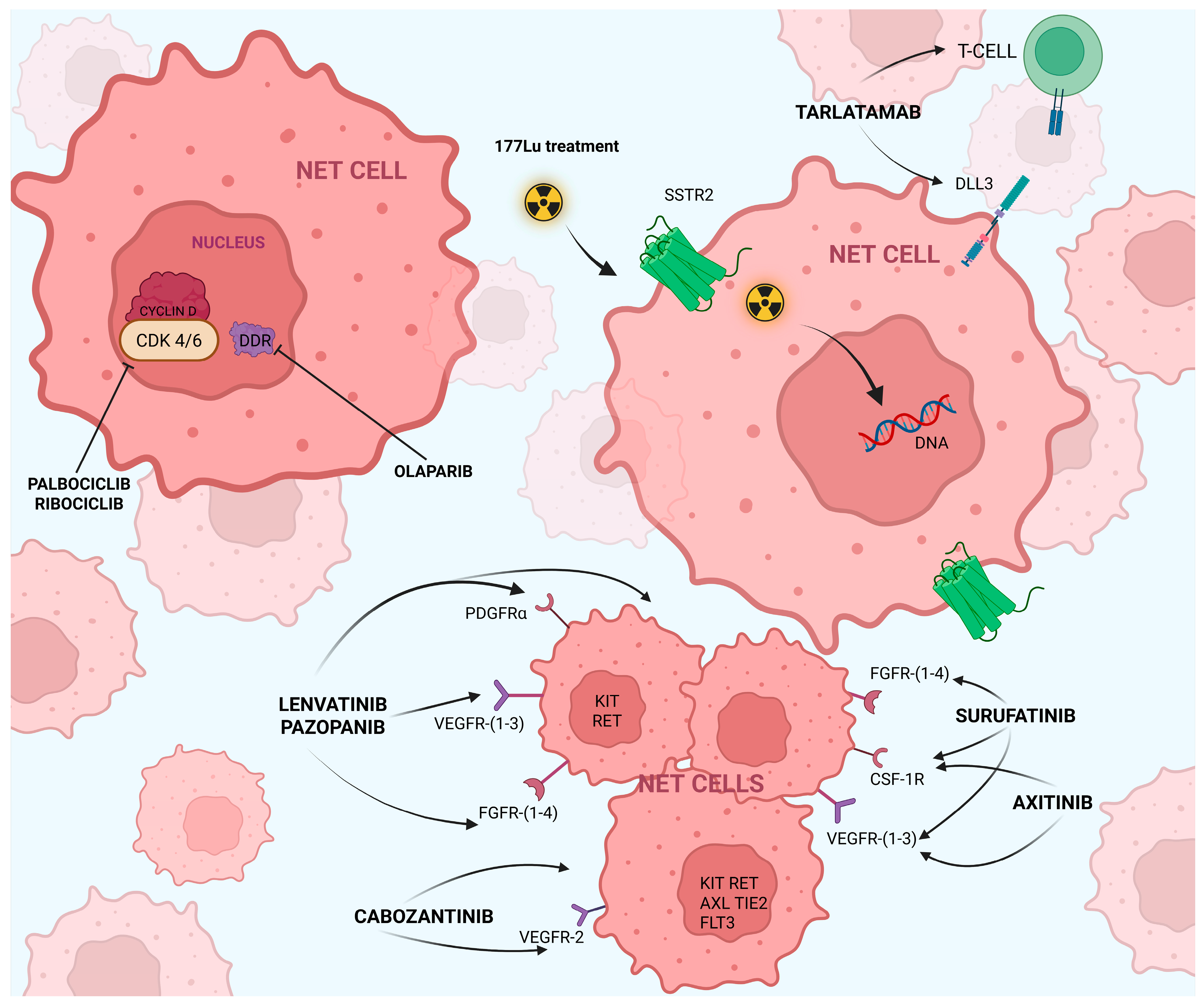

- To summarize the most recent advances in emerging systemic options, focusing on new molecularly targeted therapies and immunotherapeutic agents;

- −

- To review novel approaches to PRRT and innovative PRRT technologies;

- −

- To discuss clinical dilemmas involved in selecting the most appropriate treatment option.

2. Prognostic and Predictive Biomarkers in PanNENs

2.1. Typical Features and Molecular Biology

2.2. Molecular Targets and Signaling Pathways

3. Surgery and Locoregional Therapies

4. Chemotherapy

5. Development of SSA

6. Innovative PRRT Strategies

7. Advances in Targeted Therapies

8. Immunotherapeutic Agents

9. New Targets

10. Perspectives for Clinical and Assistive Implications

11. Conclusions and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NEN | Neuroendocrine neoplasm |

| GI-NET | Gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumor |

| PanNET | Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor |

| GEP-NEN | Gastroentero-pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm |

| GEP-NEC | Gastroentero-pancreatic carcinoma |

| NET | Neuroendocrine tumor |

| PanNEC | Pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinoma |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| MEN1 | Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 |

| VHL | Von Hippel–Lindau syndrome |

| NF-1 | Neurofibromatosis 1 |

| DAXX | Death-domain-associated protein |

| ATRX | α thalassemia/mental retardation syndrome X-linked |

| mTOR | Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| NEC | Neuroendocrine carcinoma |

| ePanNET | Extrapancreatic neuroendocrine tumor |

| GEP-NET | Gastroentero-pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor |

| TAE | Liver-directed transarterial embolization |

| TACE | Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) |

| SIRT | Selective internal radiation therapy |

| RFA | Radiofrequency ablation |

| MWA | Microwave ablation |

| EA | Ethanol ablation |

| MGMT | O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase |

| CAP-TEM | Capecitabine plus temozolomide |

| FOLFOX | Fluorouracil plus oxaliplatin |

| SSA | Somatostatin analog |

| NF-PanNET | Non-functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor |

| SSTR | Somatostatin receptor |

| PRRT | Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy |

| TNM | Tumor, Node, and Metastasis |

| PFS | Progression-free survival |

| mPFS | Median progression-free survival |

| BiTE | Bispecific T-cell engager |

| NANETS | The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| TAT | Targeted alpha therapy |

| RLT | Radioligand therapy |

| ENETS | The European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society |

| ASCO | The American Society of Clinical Oncology |

| ESMO | The European Society of Medical Oncology |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| VEGFR | Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor |

| PDGF | Platelet-derived growth factor |

| PDGFR | Platelet-derived growth factor receptor |

| FGF | Fibroblast growth factor |

| FGFR1 | Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 |

| TKI | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor |

| c-kit | Stem cell factor receptor |

| ORR | Objective response rate |

| c-MET | Mesenchymal–epithelial transition |

| CSF-1R | Colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor |

| OS | Overall survival |

| RCC | Renal cell carcinoma |

| HIF | Hypoxia-inducible factor |

| PPGL | Pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma |

| wt-GIST | Wild-type gastrointestinal stromal tumor |

| CAR | Chimeric antigen receptor |

| CTLA-4 | Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 |

| PD-1 | Programmed cell death protein -1 |

| PD-L1 | Programmed cell death protein -1 ligand |

| CR | Complete response |

| PR | Partial response |

| TMB | Tumor mutational burden |

| TMB-H | High tumor mutational burden |

| MSI | Microsatellite instability |

| RECIST | Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors |

| MMR | Mismatch repair |

| CDK | Cyclin-dependent kinase |

| DLL3 | Delta-like ligand 3 |

| HDAC | Histone deacetylase |

| ADC | Antibody–drug conjugate |

| CTL | Cytotoxic T lymphocyte |

| HAT | Histone acetyltransferases |

| NAMPT | Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| MDT | Multidisciplinary team |

References

- Oronsky, B.; Ma, P.C.; Morgensztern, D.; Carter, C.A. Nothing But NET: A Review of Neuroendocrine Tumors and Carcinomas. Neoplasia 2017, 19, 991–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cives, M.; Strosberg, J.R. Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 471–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasari, A.; Shen, C.; Halperin, D.; Zhao, B.; Zhou, S.; Xu, Y.; Shih, T.; Yao, J.C. Trends in the Incidence, Prevalence, and Survival Outcomes in Patients with Neuroendocrine Tumors in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 1335–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durma, A.D.; Saracyn, M.; Kołodziej, M.; Jóźwik-Plebanek, K.; Dmochowska, B.; Kapusta, W.; Żmudzki, W.; Mróz, A.; Kos-Kudła, B.; Kamiński, G. Epidemiology of Neuroendocrine Neoplasms and Results of Their Treatment with [(177)Lu]Lu-DOTA-TATE or [(177)Lu]Lu-DOTA-TATE and [(90)Y]Y-DOTA-TATE—A Six-Year Experience in High-Reference Polish Neuroendocrine Neoplasm Center. Cancers 2023, 15, 5466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, J.R.; Merchant, N.B.; Conrad, C.; Keutgen, X.M.; Hallet, J.; Drebin, J.A.; Minter, R.M.; Lairmore, T.C.; Tseng, J.F.; Zeh, H.J.; et al. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society Consensus Paper on the Surgical Management of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Pancreas 2020, 49, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leoncini, E.; Boffetta, P.; Shafir, M.; Aleksovska, K.; Boccia, S.; Rindi, G. Increased incidence trend of low-grade and high-grade neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocrine 2017, 58, 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, R.; Hayes, A.J.; Haugvik, S.P.; Hedenström, P.; Siuka, D.; Korsæth, E.; Kämmerer, D.; Robinson, S.M.; Maisonneuve, P.; Delle Fave, G.; et al. Risk and protective factors for the occurrence of sporadic pancreatic endocrine neoplasms. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2017, 24, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben, Q.; Zhong, J.; Fei, J.; Chen, H.; Yv, L.; Tan, J.; Yuan, Y. Risk Factors for Sporadic Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Case-Control Study. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.A.; Ribeiro-Oliveira, A., Jr.; Houchard, A.; Dennen, S.; Liu, Y.; Naga, S.S.B.; Zhao, Y.; Pommie, C.; Vandamme, T.; Starr, J. Burden of Comorbidities and Concomitant Medications and Their Associated Costs in Patients with Gastroenteropancreatic or Lung Neuroendocrine Tumors: Analysis of US Administrative Data. Adv. Ther. 2025, 42, 2190–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darbà, J.; Marsà, A. Exploring the current status of neuroendocrine tumours: A population-based analysis of epidemiology, management and use of resources. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poddighe, D. Pancreatic Comorbidities in Pediatric Celiac Disease: Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency, Pancreatitis, and Diabetes Mellitus. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pes, L.; La Salvia, A.; Pes, G.M.; Dore, M.P.; Fanciulli, G. Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms and Celiac Disease: Rare or Neglected Association? J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernieri, C.; Pusceddu, S.; Fucà, G.; Indelicato, P.; Centonze, G.; Castagnoli, L.; Ferrari, E.; Ajazi, A.; Pupa, S.; Casola, S.; et al. Impact of systemic and tumor lipid metabolism on everolimus efficacy in advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (pNETs). Int. J. Cancer 2019, 144, 1704–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faggiano, A.; Modica, R.; Lo Calzo, F.; Camera, L.; Napolitano, V.; Altieri, B.; de Cicco, F.; Bottiglieri, F.; Sesti, F.; Badalamenti, G.; et al. Lanreotide Therapy vs Active Surveillance in MEN1-Related Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors < 2 Centimeters. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 105, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri, R.M.; Benevento, E.; De Cicco, F.; Fazzalari, B.; Guadagno, E.; Hasballa, I.; Tarsitano, M.G.; Isidori, A.M.; Colao, A.; Faggiano, A. Neuroendocrine neoplasms in the context of inherited tumor syndromes: A reappraisal focused on targeted therapies. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2023, 46, 213–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevere, M.; Gkountakos, A.; Martelli, F.M.; Scarpa, A.; Luchini, C.; Simbolo, M. An Insight on Functioning Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehehalt, F.; Franke, E.; Pilarsky, C.; Grützmann, R. Molecular pathogenesis of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Cancers 2010, 2, 1901–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, Y.; Shi, C.; Edil, B.H.; de Wilde, R.F.; Klimstra, D.S.; Maitra, A.; Schulick, R.D.; Tang, L.H.; Wolfgang, C.L.; Choti, M.A.; et al. DAXX/ATRX, MEN1, and mTOR pathway genes are frequently altered in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Science 2011, 331, 1199–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colapietra, F.; Della Monica, P.; Di Napoli, R.; França Vieira, E.S.F.; Settembre, G.; Marino, M.M.; Ballini, A.; Cantore, S.; Di Domenico, M. Epigenetic Modifications as Novel Biomarkers for Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Therapeutic Targeting in Thyroid, Pancreas, and Lung Neuroendocrine Tumors. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfdanarson, T.R.; Rabe, K.G.; Rubin, J.; Petersen, G.M. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs): Incidence, prognosis and recent trend toward improved survival. Ann. Oncol. 2008, 19, 1727–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, T.; Igarashi, H.; Nakamura, K.; Sasano, H.; Okusaka, T.; Takano, K.; Komoto, I.; Tanaka, M.; Imamura, M.; Jensen, R.T.; et al. Epidemiological trends of pancreatic and gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors in Japan: A nationwide survey analysis. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 50, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorbye, H.; Grande, E.; Pavel, M.; Tesselaar, M.; Fazio, N.; Reed, N.S.; Knigge, U.; Christ, E.; Ambrosini, V.; Couvelard, A.; et al. European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) 2023 guidance paper for digestive neuroendocrine carcinoma. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2023, 35, e13249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanno, Y.; Toyama, H.; Ueshima, E.; Sofue, K.; Matsumoto, I.; Ishida, J.; Urade, T.; Fukushima, K.; Gon, H.; Tsugawa, D.; et al. Transarterial chemoembolization for liver metastases of a pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm: A single-center experience. Surg. Today 2023, 53, 1396–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knigge, U.; Hansen, C.P. Surgery for GEP-NETs. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2012, 26, 819–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeune, F.; Taibi, A.; Gaujoux, S. Update on the Surgical Treatment of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Scand. J. Surg. 2020, 109, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starzyńska, T.; Londzin-Olesik, M.; Bednarczuk, T.; Bolanowski, M.; Borowska, M.; Chmielik, E.; Ćwikła, J.B.; Foltyn, W.; Gisterek, I.; Handkiewicz-Junak, D.; et al. Colorectal neuroendocrine neoplasms—Update of the diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines (recommended by the Polish Network of Neuroendocrine Tumours) [Nowotwory neuroendokrynne jelita grubego—Uaktualnione zasady diagnostyki i leczenia (rekomendowane przez Polską Sieć Guzów Neuroendokrynych)]. Endokrynol. Pol. 2022, 73, 584–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kos-Kudła, B.; Castaño, J.P.; Denecke, T.; Grande, E.; Kjaer, A.; Koumarianou, A.; de Mestier, L.; Partelli, S.; Perren, A.; Stättner, S.; et al. European Neuroendocrine Tumour Society (ENETS) 2023 guidance paper for nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2023, 35, e13343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, I.; Shimizu, N.; Seto, Y. Treatment of neuroendocrine tumors of the digestive tract. Gan Kagaku Ryoho 2009, 36, 1606–1610. [Google Scholar]

- Sedlack, A.J.H.; Varghese, D.G.; Naimian, A.; Yazdian Anari, P.; Bodei, L.; Hallet, J.; Riechelmann, R.P.; Halfdanarson, T.; Capdevilla, J.; Del Rivero, J. Update in the management of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer 2024, 130, 3090–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavel, M.; Öberg, K.; Falconi, M.; Krenning, E.P.; Sundin, A.; Perren, A.; Berruti, A. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 844–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, B.; Sirohi, B.; Corrie, P. Systemic therapy for neuroendocrine tumours of gastroenteropancreatic origin. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2010, 17, R75–R90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindi, G.; Mete, O.; Uccella, S.; Basturk, O.; La Rosa, S.; Brosens, L.A.A.; Ezzat, S.; de Herder, W.W.; Klimstra, D.S.; Papotti, M.; et al. Overview of the 2022 WHO Classification of Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Endocr Pathol 2022, 33, 115–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindi, G.; Klimstra, D.S.; Abedi-Ardekani, B.; Asa, S.L.; Bosman, F.T.; Brambilla, E.; Busam, K.J.; de Krijger, R.R.; Dietel, M.; El-Naggar, A.K.; et al. A common classification framework for neuroendocrine neoplasms: An International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and World Health Organization (WHO) expert consensus proposal. Mod. Pathol. 2018, 31, 1770–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melhorn, P.; Spitzer, J.; Adel, T.; Wolff, L.; Mazal, P.; Raderer, M.; Kiesewetter, B. Patterns and outcomes of current antitumor therapy for high-grade neuroendocrine neoplasms: Perspective of a tertiary referral center. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 151, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arakelyan, J.; Zohrabyan, D.; Philip, P.A. Molecular profile of pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (PanNENs): Opportunities for personalized therapies. Cancer 2021, 127, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundin, A.; Arnold, R.; Baudin, E.; Cwikla, J.B.; Eriksson, B.; Fanti, S.; Fazio, N.; Giammarile, F.; Hicks, R.J.; Kjaer, A.; et al. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the Standards of Care in Neuroendocrine Tumors: Radiological, Nuclear Medicine & Hybrid Imaging. Neuroendocrinology 2017, 105, 212–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar-Moshe, Y.; Mazeh, H.; Grozinsky-Glasberg, S. Non-functioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: Surgery or observation? World J. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2017, 9, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.B.; Fan, Y.B.; Jing, R.; Getu, M.A.; Chen, W.Y.; Zhang, W.; Dong, H.X.; Dakal, T.C.; Hayat, A.; Cai, H.J.; et al. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: Current development, challenges, and clinical perspectives. Mil. Med. Res. 2024, 11, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.; Zhang, B.; Chen, H. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: Epidemiology, genetics, and treatment. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1424839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarbassov, D.D.; Ali, S.M.; Sabatini, D.M. Growing roles for the mTOR pathway. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2005, 17, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozzi, M.; Caterina, I.; De Divitiis, C.; von Arx, C.; Maiolino, P.; Tatangelo, F.; Cavalcanti, E.; Di Girolamo, E.; Iaffaioli, R.V.; Scala, S.; et al. Everolimus and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs): Activity, resistance and how to overcome it. Int. J. Surg. 2015, 21 (Suppl. 1), S89–S94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharjan, C.K.; Ear, P.H.; Tran, C.G.; Howe, J.R.; Chandrasekharan, C.; Quelle, D.E. Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets. Cancers 2021, 13, 5117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.; Tang, L.H.; Davidson, C.; Vosburgh, E.; Chen, W.; Foran, D.J.; Notterman, D.A.; Levine, A.J.; Xu, E.Y. Two well-differentiated pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor mouse models. Cell Death Differ. 2020, 27, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peyressatre, M.; Prével, C.; Pellerano, M.; Morris, M.C. Targeting cyclin-dependent kinases in human cancers: From small molecules to Peptide inhibitors. Cancers 2015, 7, 179–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Q.; Guo, X.; Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Sun, X.; Li, Q. The application and prospect of CDK4/6 inhibitors in malignant solid tumors. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, M.J.; Gervaso, L.; Meneses-Medina, M.I.; Spada, F.; Abdel-Rahman, O.; Fazio, N. Cyclin-dependent Kinases 4/6 Inhibitors in Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: From Bench to Bedside. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2022, 24, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takebe, N.; Miele, L.; Harris, P.J.; Jeong, W.; Bando, H.; Kahn, M.; Yang, S.X.; Ivy, S.P. Targeting Notch, Hedgehog, and Wnt pathways in cancer stem cells: Clinical update. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 12, 445–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristizabal Prada, E.T.; Auernhammer, C.J. Targeted therapy of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours: Preclinical strategies and future targets. Endocr. Connect. 2018, 7, R1–R25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Wang, R.; Ma, X.; Jiang, K.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z.; Long, T.; Lu, M.; et al. Exploring the expression of DLL3 in gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms and its potential diagnostic value. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochmanová, I.; Zelinka, T.; Widimský, J., Jr.; Pacak, K. HIF signaling pathway in pheochromocytoma and other neuroendocrine tumors. Physiol. Res. 2014, 63 (Suppl. 2), S251–S262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, R.A.; Jimenez, C.; Armaiz-Pena, G.; Arenillas, C.; Capdevila, J.; Dahia, P.L.M. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 2 Alpha (HIF2α) Inhibitors: Targeting Genetically Driven Tumor Hypoxia. Endocr. Rev. 2023, 44, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciejewski, K.; Buchalska, B.; Solnik, M.; Fudalej, M.; Deptała, A.; Badowska-Kozakiewicz, A. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours—An overview. Med. Stud. Stud. Med. 2022, 38, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, M.E.; Puccini, A.; Grothey, A.; Raghavan, D.; Goldberg, R.M.; Xiu, J.; Korn, W.M.; Weinberg, B.A.; Hwang, J.J.; Shields, A.F.; et al. Landscape of Tumor Mutation Load, Mismatch Repair Deficiency, and PD-L1 Expression in a Large Patient Cohort of Gastrointestinal Cancers. Mol. Cancer Res. 2018, 16, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallis, C.J.D.; Lawson, K.; Butaney, M.; Satkunasivam, R.; Parikh, J.; Freedland, S.J.; Patel, S.P.; Hamid, O.; Pal, S.K.; Klaassen, Z. Association between PD-L1 status and immune checkpoint inhibitor response in advanced malignancies: A systematic review and meta-analysis of overall survival data. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 50, 800–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, H.; Sanchez-Vega, F.; La, K.; Chatila, W.; Jonsson, P.; Halpenny, D.; Plodkowski, A.; Long, N.; Sauter, J.L.; Rekhtman, N.; et al. Molecular Determinants of Response to Anti-Programmed Cell Death (PD)-1 and Anti-Programmed Death-Ligand 1 (PD-L1) Blockade in Patients with Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Profiled with Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, A.; Bowden, M.; Zhang, S.; Masugi, Y.; Thorner, A.R.; Herbert, Z.T.; Zhou, C.W.; Brais, L.; Chan, J.A.; Hodi, F.S.; et al. Characterization of the Neuroendocrine Tumor Immune Microenvironment. Pancreas 2018, 47, 1123–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oktay, E.; Yalcin, G.D.; Ekmekci, S.; Kahraman, D.S.; Yalcin, A.; Degirmenci, M.; Dirican, A.; Altin, Z.; Ozdemir, O.; Surmeli, Z.; et al. Programmed cell death ligand-1 expression in gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. J. Buon 2019, 24, 779–790. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, A.T.; Howe, J.R. Evaluation and Management of Neuroendocrine Tumors of the Pancreas. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 99, 793–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidani, K.; Marinovic, A.G.; Moond, V.; Harne, P.; Broder, A.; Thosani, N. Treatment of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: Beyond Traditional Surgery and Targeted Therapy. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mestier, L.; Zappa, M.; Hentic, O.; Vilgrain, V.; Ruszniewski, P. Liver transarterial embolizations in metastatic neuroendocrine tumors. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2017, 18, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, R.; Mohammed, A.; Singh, A.; Harnegie, M.P.; Rustagi, T.; Stevens, T.; Chahal, P. EUS-guided radiofrequency and ethanol ablation for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Endosc. Ultrasound 2022, 11, 170–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Partelli, S.; Cirocchi, R.; Rancoita, P.M.V.; Muffatti, F.; Andreasi, V.; Crippa, S.; Tamburrino, D.; Falconi, M. A Systematic review and meta-analysis on the role of palliative primary resection for pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm with liver metastases. HPB 2018, 20, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamarca, A.; Elliott, E.; Barriuso, J.; Backen, A.; McNamara, M.G.; Hubner, R.; Valle, J.W. Chemotherapy for advanced non-pancreatic well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumours of the gastrointestinal tract, a systematic review and meta-analysis: A lost cause? Cancer Treat. Rev. 2016, 44, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.L.; Singh, S. Current Chemotherapy Use in Neuroendocrine Tumors. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 47, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, H.; Gerson, D.S.; Reidy-Lagunes, D.; Raj, N. Systemic Therapies for Metastatic Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2019, 20, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheless, M.; Das, S. Systemic Therapy for Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Clin. Color. Cancer 2023, 22, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.L.; Cheng, Z.X.; Yu, F.H.; Tian, C.; Tan, H.Y. Advances in medical treatment for pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. World J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 2163–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trillo Aliaga, P.; Spada, F.; Peveri, G.; Bagnardi, V.; Fumagalli, C.; Laffi, A.; Rubino, M.; Gervaso, L.; Guerini Rocco, E.; Pisa, E.; et al. Should temozolomide be used on the basis of O(6)-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase status in patients with advanced neuroendocrine tumors? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2021, 99, 102261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunz, P.L.; Graham, N.T.; Catalano, P.J.; Nimeiri, H.S.; Fisher, G.A.; Longacre, T.A.; Suarez, C.J.; Martin, B.A.; Yao, J.C.; Kulke, M.H.; et al. Randomized Study of Temozolomide or Temozolomide and Capecitabine in Patients with Advanced Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors (ECOG-ACRIN E2211). J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 1359–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rivero, J.; Perez, K.; Kennedy, E.B.; Mittra, E.S.; Vijayvergia, N.; Arshad, J.; Basu, S.; Chauhan, A.; Dasari, A.N.; Bellizzi, A.M.; et al. Systemic Therapy for Tumor Control in Metastatic Well-Differentiated Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: ASCO Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 5049–5067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Toubah, T.; Morse, B.; Pelle, E.; Strosberg, J. Efficacy of FOLFOX in Patients with Aggressive Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors After Prior Capecitabine/Temozolomide. Oncologist 2021, 26, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrasekharan, C. Medical Management of Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 29, 293–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panzuto, F.; Ricci, C.; Rinzivillo, M.; Magi, L.; Marasco, M.; Lamberti, G.; Casadei, R.; Campana, D. The Antiproliferative Activity of High-Dose Somatostatin Analogs in Gastro-Entero-Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, A.; Strosberg, J.R. Medical Management of Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: Current Strategies and Future Advances. J. Nucl. Med. 2019, 60, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strosberg, J.R.; Halfdanarson, T.R.; Bellizzi, A.M.; Chan, J.A.; Dillon, J.S.; Heaney, A.P.; Kunz, P.L.; O’Dorisio, T.M.; Salem, R.; Segelov, E.; et al. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society Consensus Guidelines for Surveillance and Medical Management of Midgut Neuroendocrine Tumors. Pancreas 2017, 46, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinke, A.; Müller, H.H.; Schade-Brittinger, C.; Klose, K.J.; Barth, P.; Wied, M.; Mayer, C.; Aminossadati, B.; Pape, U.F.; Bläker, M.; et al. Placebo-controlled, double-blind, prospective, randomized study on the effect of octreotide LAR in the control of tumor growth in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine midgut tumors: A report from the PROMID Study Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 4656–4663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplin, M.E.; Pavel, M.; Ćwikła, J.B.; Phan, A.T.; Raderer, M.; Sedláčková, E.; Cadiot, G.; Wolin, E.M.; Capdevila, J.; Wall, L.; et al. Lanreotide in metastatic enteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavel, M.; Ćwikła, J.B.; Lombard-Bohas, C.; Borbath, I.; Shah, T.; Pape, U.F.; Capdevila, J.; Panzuto, F.; Truong Thanh, X.M.; Houchard, A.; et al. Efficacy and safety of high-dose lanreotide autogel in patients with progressive pancreatic or midgut neuroendocrine tumours: CLARINET FORTE phase 2 study results. Eur. J. Cancer 2021, 157, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, G.; Dicitore, A.; Sciammarella, C.; Di Molfetta, S.; Rubino, M.; Faggiano, A.; Colao, A. Pasireotide in the treatment of neuroendocrine tumors: A review of the literature. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2018, 25, R351–R364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.; Blanchard, M.P.; Albertelli, M.; Barbieri, F.; Brue, T.; Niccoli, P.; Delpero, J.R.; Monges, G.; Garcia, S.; Ferone, D.; et al. Pasireotide and octreotide antiproliferative effects and sst2 trafficking in human pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor cultures. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2014, 21, 691–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes-Porras, M.; Cárdenas-Salas, J.; Álvarez-Escolá, C. Somatostatin Analogs in Clinical Practice: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolin, E.M.; Jarzab, B.; Eriksson, B.; Walter, T.; Toumpanakis, C.; Morse, M.A.; Tomassetti, P.; Weber, M.M.; Fogelman, D.R.; Ramage, J.; et al. Phase III study of pasireotide long-acting release in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine tumors and carcinoid symptoms refractory to available somatostatin analogues. Drug Des. Devel Ther. 2015, 9, 5075–5086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulke, M.H.; Ruszniewski, P.; Van Cutsem, E.; Lombard-Bohas, C.; Valle, J.W.; De Herder, W.W.; Pavel, M.; Degtyarev, E.; Brase, J.C.; Bubuteishvili-Pacaud, L.; et al. A randomized, open-label, phase 2 study of everolimus in combination with pasireotide LAR or everolimus alone in advanced, well-differentiated, progressive pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: COOPERATE-2 trial. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 1309–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stueven, A.K.; Kayser, A.; Wetz, C.; Amthauer, H.; Wree, A.; Tacke, F.; Wiedenmann, B.; Roderburg, C.; Jann, H. Somatostatin Analogues in the Treatment of Neuroendocrine Tumors: Past, Present and Future. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Zwan, W.A.; Bodei, L.; Mueller-Brand, J.; de Herder, W.W.; Kvols, L.K.; Kwekkeboom, D.J. GEPNETs update: Radionuclide therapy in neuroendocrine tumors. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 172, R1–R8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papotti, M.; Bongiovanni, M.; Volante, M.; Allìa, E.; Landolfi, S.; Helboe, L.; Schindler, M.; Cole, S.L.; Bussolati, G. Expression of somatostatin receptor types 1-5 in 81 cases of gastrointestinal and pancreatic endocrine tumors. A correlative immunohistochemical and reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction analysis. Virchows Arch. 2002, 440, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Al-Toubah, T.; El-Haddad, G.; Strosberg, J. (177)Lu-DOTATATE for the treatment of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Expert. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 13, 1023–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lastoria, S.; Rodari, M.; Sansovini, M.; Baldari, S.; D’Agostini, A.; Cervino, A.R.; Filice, A.; Salgarello, M.; Perotti, G.; Nieri, A.; et al. Lutetium [(177)Lu]-DOTA-TATE in gastroenteropancreatic-neuroendocrine tumours: Rationale, design and baseline characteristics of the Italian prospective observational (REAL-LU) study. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2024, 51, 3417–3427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brabander, T.; van der Zwan, W.A.; Teunissen, J.J.M.; Kam, B.L.R.; Feelders, R.A.; de Herder, W.W.; van Eijck, C.H.J.; Franssen, G.J.H.; Krenning, E.P.; Kwekkeboom, D.J. Long-Term Efficacy, Survival, and Safety of [(177)Lu-DOTA(0),Tyr(3)]octreotate in Patients with Gastroenteropancreatic and Bronchial Neuroendocrine Tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 4617–4624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciuciulkaite, I.; Herrmann, K.; Lahner, H. Importance of peptide receptor radionuclide therapy for the management of neuroendocrine tumours. Radiologie 2025, 65, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Halperin, D.; Myrehaug, S.; Herrmann, K.; Pavel, M.; Kunz, P.L.; Chasen, B.; Tafuto, S.; Lastoria, S.; Capdevila, J.; et al. [(177)Lu]Lu-DOTA-TATE plus long-acting octreotide versus high—dose long-acting octreotide for the treatment of newly diagnosed, advanced grade 2-3, well-differentiated, gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (NETTER-2): An open-label, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet 2024, 403, 2807–2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavel, M.E.; Rinke, A.; Baum, R.P. COMPETE trial: Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) with 177Lu-edotreotide vs. everolimus in progressive GEP-NET. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, viii478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, R.; Raja, S.; Adusumilli, A.; Gopireddy, M.M.R.; Loveday, B.P.T.; Alipour, R.; Kong, G. Role of neoadjuvant peptide receptor radionuclide therapy in unresectable and metastatic gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: A scoping review. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2025, 37, e13425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lania, A.; Ferraù, F.; Rubino, M.; Modica, R.; Colao, A.; Faggiano, A. Neoadjuvant Therapy for Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Recent Progresses and Future Approaches. Front Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 651438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuiper, J.; Zoetelief, E.; Brabander, T.; de Herder, W.W.; Hofland, J. Current status of peptide receptor radionuclide therapy in grade 1 and 2 gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2025, 37, e13469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partelli, S.; Landoni, L.; Bartolomei, M.; Zerbi, A.; Grana, C.M.; Boggi, U.; Butturini, G.; Casadei, R.; Salvia, R.; Falconi, M. Neoadjuvant 177Lu-DOTATATE for non-functioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (NEOLUPANET): Multicentre phase II study. Br. J. Surg. 2024, 111, znae178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navalkissoor, S.; Grossman, A. Targeted Alpha Particle Therapy for Neuroendocrine Tumours: The Next Generation of Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy. Neuroendocrinology 2019, 108, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Jakobsson, V.; Greifenstein, L.; Khong, P.L.; Chen, X.; Baum, R.P.; Zhang, J. Alpha-peptide receptor radionuclide therapy using actinium-225 labeled somatostatin receptor agonists and antagonists. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 1034315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhimaniya, S.; Shah, H.; Jacene, H.A. Alpha-emitter Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy in Neuroendocrine Tumors. PET Clin. 2024, 19, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballal, S.; Yadav, M.P.; Bal, C.; Sahoo, R.K.; Tripathi, M. Broadening horizons with (225)Ac-DOTATATE targeted alpha therapy for gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumour patients stable or refractory to (177)Lu-DOTATATE PRRT: First clinical experience on the efficacy and safety. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2020, 47, 934–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papachristou, M. Radiopharmaceuticals used for diagnosis and therapy of NETs. Hell. J. Nucl. Med. 2023, 26, 19–20. [Google Scholar]

- Puliani, G.; Chiefari, A.; Mormando, M.; Bianchini, M.; Lauretta, R.; Appetecchia, M. New Insights in PRRT: Lessons From 2021. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 861434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.I. Salvage peptide receptor radionuclide therapy in patients with progressive neuroendocrine tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nucl. Med. Commun. 2021, 42, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strosberg, J.; Leeuwenkamp, O.; Siddiqui, M.K. Peptide receptor radiotherapy re-treatment in patients with progressive neuroendocrine tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2021, 93, 102141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panzuto, F.; Albertelli, M.; De Rimini, M.L.; Rizzo, F.M.; Grana, C.M.; Cives, M.; Faggiano, A.; Versari, A.; Tafuto, S.; Fazio, N.; et al. Radioligand therapy in the therapeutic strategy for patients with gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: A consensus statement from the Italian Association for Neuroendocrine Tumors (Itanet), Italian Association of Nuclear Medicine (AIMN), Italian Society of Endocrinology (SIE), Italian Association of Medical Oncology (AIOM). J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2025, 48, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohindroo, C.; McAllister, F.; De Jesus-Acosta, A. Genetics of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2022, 36, 1033–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, H.; Lam, A.K. Pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: Updates on genomic changes in inherited tumour syndromes and sporadic tumours based on WHO classification. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2022, 172, 103648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasskarl, J. Everolimus. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2018, 211, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.C.; Shah, M.H.; Ito, T.; Bohas, C.L.; Wolin, E.M.; Van Cutsem, E.; Hobday, T.J.; Okusaka, T.; Capdevila, J.; de Vries, E.G.; et al. Everolimus for advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanini, S.; Renzi, S.; Giovinazzo, F.; Bermano, G. mTOR Pathway in Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor (GEP-NETs). Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 562505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinke, A.; Krug, S. Neuroendocrine tumours—Medical therapy: Biological. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 30, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimoyama, R.; Hijioka, S.; Mizuno, N.; Ogawa, G.; Kataoka, T.; Katayama, H.; Machida, N.; Honma, Y.; Boku, N.; Hamaguchi, T.; et al. Study protocol for a multi-institutional randomized phase III study comparing combined everolimus plus lanreotide therapy and everolimus monotherapy in patients with unresectable or recurrent gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors; Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study JCOG1901 (STARTER-NET study). Pancreatology 2020, 20, 1183–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hijioka, S.; Honma, Y.; Machida, N.; Mizuno, N.; Hamaguchi, T.; Boku, N.; Sadachi, R.; Hiraoka, N.; Okusaka, T.; Hirano, H.; et al. A phase III study of combination therapy with everolimus plus lanreotide versus everolimus monotherapy for unresectable or recurrent gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (JCOG1901, STARTER-NET). J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43 (Suppl. 4), 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cives, M.; Pelle, E.; Quaresmini, D.; Rizzo, F.M.; Tucci, M.; Silvestris, F. The Tumor Microenvironment in Neuroendocrine Tumors: Biology and Therapeutic Implications. Neuroendocrinology 2019, 109, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, P.; Zuazo-Gaztelu, I.; Casanovas, O. Sprouting strategies and dead ends in anti-angiogenic targeting of NETs. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2017, 59, R77–R91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, N.; Kulke, M.; Rosbrook, B.; Fernandez, K.; Raymond, E. Updated Efficacy and Safety Outcomes for Patients with Well-Differentiated Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors Treated with Sunitinib. Target. Oncol. 2021, 16, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulke, M.H.; Lenz, H.J.; Meropol, N.J.; Posey, J.; Ryan, D.P.; Picus, J.; Bergsland, E.; Stuart, K.; Tye, L.; Huang, X.; et al. Activity of sunitinib in patients with advanced neuroendocrine tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 3403–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, E.; Dahan, L.; Raoul, J.L.; Bang, Y.J.; Borbath, I.; Lombard-Bohas, C.; Valle, J.; Metrakos, P.; Smith, D.; Vinik, A.; et al. Sunitinib malate for the treatment of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, G.M.; Cortazar, P.; Zhang, J.J.; Tang, S.; Sridhara, R.; Murgo, A.; Justice, R.; Pazdur, R. FDA approval summary: Sunitinib for the treatment of progressive well-differentiated locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Oncologist 2012, 17, 1108–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, E.; Rodriguez-Antona, C.; López, C.; Alonso-Gordoa, T.; Benavent, M.; Capdevila, J.; Teulé, A.; Custodio, A.; Sevilla, I.; Hernando, J.; et al. Sunitinib and Evofosfamide (TH-302) in Systemic Treatment-Naïve Patients with Grade 1/2 Metastatic Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: The GETNE-1408 Trial. Oncologist 2021, 26, 941–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochin, V.; Gross-Goupil, M.; Ravaud, A.; Godbert, Y.; Le Moulec, S. Cabozantinib: Mechanism of action, efficacy and indications. Bull. Cancer 2017, 104, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.A.; Geyer, S.; Zemla, T.; Knopp, M.V.; Behr, S.; Pulsipher, S.; Ou, F.S.; Dueck, A.C.; Acoba, J.; Shergill, A.; et al. Phase 3 Trial of Cabozantinib to Treat Advanced Neuroendocrine Tumors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.; Geyer, S.; Zemla, T.; Knopp, M.V.; Behr, S.C.; Pulsipher, S.; Acoba, J.; Shergill, A.; Wolin, E.M.; Halfdanarson, T.R.; et al. 1141O Cabozantinib versus placebo for advanced neuroendocrine tumors (NET) after progression on prior therapy (CABINET Trial/Alliance A021602): Updated results including progression free-survival (PFS) by blinded independent central review (BICR) and subgroup analyses. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, S749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killock, D. CABINET presents cabozantinib as a new treatment option for NETs. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 21, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. Current treatments and future potential of surufatinib in neuroendocrine tumors (NETs). Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2021, 13, 17588359211042689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Li, J.; Bai, C.; Xu, N.; Zhou, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhou, C.; Jia, R.; Lu, M.; Cheng, Y.; et al. Surufatinib in Advanced Well-Differentiated Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Multicenter, Single-Arm, Open-Label, Phase Ib/II Trial. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 3486–3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Shen, L.; Bai, C.; Wang, W.; Li, J.; Yu, X.; Li, Z.; Li, E.; Yuan, X.; Chi, Y.; et al. Surufatinib in advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (SANET-p): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 1489–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Shen, L.; Zhou, Z.; Li, J.; Bai, C.; Chi, Y.; Li, Z.; Xu, N.; Li, E.; Liu, T.; et al. Surufatinib in advanced extrapancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (SANET-ep): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 1500–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Shen, L.; Li, J.; Zhou, Z.; Bai, C.; Li, Z.; Chi, Y.; Li, E.; Yu, X.; Xu, N.; et al. Surufatinib in advanced neuroendocrine tumours: Final overall survival from two randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 studies (SANET-ep and SANET-p). Eur. J. Cancer 2025, 222, 115398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Shen, L. Chinese multidisciplinary expert consensus on the rational use of surufatinib in clinical practice (2024 edition). Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi 2024, 46, 930–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasari, A.; Hamilton, E.P.; Falchook, G.S.; Wang, J.S.; Li, D.; Sung, M.W.; Chien, C.; Nanda, S.; Tucci, C.; Hahka-Kemppinen, M.; et al. A dose escalation/expansion study evaluating dose, safety, and efficacy of the novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor surufatinib, which inhibits VEGFR 1, 2, & 3, FGFR 1, and CSF1R, in US patients with neuroendocrine tumors. Investig. New Drugs 2023, 41, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebenhüner, A.R.; Refardt, J.; Nicolas, G.P.; Kaderli, R.; Walter, M.A.; Perren, A.; Christ, E. Impact of multikinase inhibitors in reshaping the treatment of advanced gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2025, 32, e250052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabanillas, M.E.; Habra, M.A. Lenvatinib: Role in thyroid cancer and other solid tumors. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2016, 42, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capdevila, J.; Fazio, N.; Lopez, C.; Teulé, A.; Valle, J.W.; Tafuto, S.; Custodio, A.; Reed, N.; Raderer, M.; Grande, E.; et al. Lenvatinib in Patients with Advanced Grade 1/2 Pancreatic and Gastrointestinal Neuroendocrine Tumors: Results of the Phase II TALENT Trial (GETNE1509). J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 2304–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongiovanni, A.; Liverani, C.; Recine, F.; Fausti, V.; Mercatali, L.; Vagheggini, A.; Spadazzi, C.; Miserocchi, G.; Cocchi, C.; Di Menna, G.; et al. Phase-II Trials of Pazopanib in Metastatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasia (mNEN): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, H.K.; Choi, J.Y.; Kim, K.M.; Kim, H.; Choi, S.H.; Park, S.H.; Park, J.O.; Lim, H.Y.; Kang, W.K.; Lee, J.; et al. Phase II study of pazopanib monotherapy in metastatic gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 109, 1414–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taboada, R.G.; Cavalher, F.P.; Rego, J.F.; Riechelmann, R.P. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors in patients with neuroendocrine neoplasms: A systematic literature review. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2024, 16, 17588359241286751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinato, D.J.; Tan, T.M.; Toussi, S.T.; Ramachandran, R.; Martin, N.; Meeran, K.; Ngo, N.; Dina, R.; Sharma, R. An expression signature of the angiogenic response in gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumours: Correlation with tumour phenotype and survival outcomes. Br. J. Cancer 2014, 110, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, L.; Soleimani, M. Belzutifan: A novel therapeutic for the management of von Hippel-Lindau disease and beyond. Future Oncol. 2024, 20, 1251–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonasch, E.; Donskov, F.; Iliopoulos, O.; Rathmell, W.K.; Narayan, V.K.; Maughan, B.L.; Oudard, S.; Else, T.; Maranchie, J.K.; Welsh, S.J.; et al. Belzutifan for Renal Cell Carcinoma in von Hippel-Lindau Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 2036–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Else, T.; Jonasch, E.; Iliopoulos, O.; Beckermann, K.E.; Narayan, V.; Maughan, B.L.; Oudard, S.; Maranchie, J.K.; Iversen, A.B.; Goldberg, C.M.; et al. Belzutifan for von Hippel-Lindau Disease: Pancreatic Lesion Population of the Phase 2 LITESPARK-004 Study. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 1750–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeks, E.D. Belzutifan: First Approval. Drugs 2021, 81, 1921–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reck, M.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Robinson, A.G.; Hui, R.; Csőszi, T.; Fülöp, A.; Gottfried, M.; Peled, N.; Tafreshi, A.; Cuffe, S.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus Chemotherapy for PD-L1-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1823–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodi, F.S.; O’Day, S.J.; McDermott, D.F.; Weber, R.W.; Sosman, J.A.; Haanen, J.B.; Gonzalez, R.; Robert, C.; Schadendorf, D.; Hassel, J.C.; et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, R.L.; Blumenschein, G., Jr.; Fayette, J.; Guigay, J.; Colevas, A.D.; Licitra, L.; Harrington, K.; Kasper, S.; Vokes, E.E.; Even, C.; et al. Nivolumab for Recurrent Squamous-Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1856–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDermott, D.F.; Drake, C.G.; Sznol, M.; Choueiri, T.K.; Powderly, J.D.; Smith, D.C.; Brahmer, J.R.; Carvajal, R.D.; Hammers, H.J.; Puzanov, I.; et al. Survival, Durable Response, and Long-Term Safety in Patients with Previously Treated Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma Receiving Nivolumab. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 2013–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albertelli, M.; Dotto, A.; Nista, F.; Veresani, A.; Patti, L.; Gay, S.; Sciallero, S.; Boschetti, M.; Ferone, D. Present and future of immunotherapy in Neuroendocrine Tumors. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2021, 22, 615–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, N.; Abdel-Rahman, O. Immunotherapy in Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Where Are We Now? Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2021, 22, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urman, A.; Schonman, I.; De Jesus-Acosta, A. Evolving Immunotherapy Strategies in Gastrointestinal Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2025, 26, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momtaz, P.; Postow, M.A. Immunologic checkpoints in cancer therapy: Focus on the programmed death-1 (PD-1) receptor pathway. Pharmgenomics Pers. Med. 2014, 7, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchbinder, E.I.; Desai, A. CTLA-4 and PD-1 Pathways: Similarities, Differences, and Implications of Their Inhibition. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 39, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gile, J.J.; Liu, A.J.; McGarrah, P.W.; Eiring, R.A.; Hobday, T.J.; Starr, J.S.; Sonbol, M.B.; Halfdanarson, T.R. Efficacy of Checkpoint Inhibitors in Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Mayo Clinic Experience. Pancreas 2021, 50, 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.T.; Ha, S.Y.; Lee, S.; Ahn, S.; Lee, J.; Park, S.H.; Park, J.O.; Lim, H.Y.; Kang, W.K.; Kim, K.M.; et al. The Impact of PD-L1 Expression in Patients with Metastatic GEP-NETs. J. Cancer 2016, 7, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.W.; Fu, X.L.; Jiang, Y.S.; Chen, X.J.; Tao, L.Y.; Yang, J.Y.; Huo, Y.M.; Liu, W.; Zhang, J.F.; Liu, P.F.; et al. Clinical significance of programmed death 1/programmed death ligand 1 pathway in gastric neuroendocrine carcinomas. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 1684–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strosberg, J.; Mizuno, N.; Doi, T.; Grande, E.; Delord, J.P.; Shapira-Frommer, R.; Bergsland, E.; Shah, M.; Fakih, M.; Takahashi, S.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Pembrolizumab in Previously Treated Advanced Neuroendocrine Tumors: Results from the Phase II KEYNOTE-158 Study. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 2124–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marabelle, A.; Le, D.T.; Ascierto, P.A.; Di Giacomo, A.M.; De Jesus-Acosta, A.; Delord, J.P.; Geva, R.; Gottfried, M.; Penel, N.; Hansen, A.R.; et al. Efficacy of Pembrolizumab in Patients with Noncolorectal High Microsatellite Instability/Mismatch Repair-Deficient Cancer: Results from the Phase II KEYNOTE-158 Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehnert, J.M.; Bergsland, E.; O’Neil, B.H.; Santoro, A.; Schellens, J.H.M.; Cohen, R.B.; Doi, T.; Ott, P.A.; Pishvaian, M.J.; Puzanov, I.; et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of programmed death-ligand 1-positive advanced carcinoid or pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: Results from the KEYNOTE-028 study. Cancer 2020, 126, 3021–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Toubah, T.; Schell, M.J.; Morse, B.; Haider, M.; Valone, T.; Strosberg, J. Phase II study of pembrolizumab and lenvatinib in advanced well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors. ESMO Open 2024, 9, 102386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, M.A.; Crosby, E.J.; Halperin, D.M.; Uronis, H.E.; Hsu, S.D.; Hurwitz, H.I.; Rushing, C.; Bolch, E.K.; Warren, D.A.; Moyer, A.N.; et al. Phase Ib/II study of Pembrolizumab with Lanreotide depot for advanced, progressive Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PLANET). J. Neuroendocrinol. 2025, 37, e13496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.C.; Strosberg, J.; Fazio, N.; Pavel, M.E.; Bergsland, E.; Ruszniewski, P.; Halperin, D.M.; Li, D.; Tafuto, S.; Raj, N.; et al. Spartalizumab in metastatic, well/poorly differentiated neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2021, 28, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Gong, J.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Lu, Z.; et al. Efficacy, Safety, and Biomarkers of Toripalimab in Patients with Recurrent or Metastatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: A Multiple-Center Phase Ib Trial. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 2337–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, O.; Kee, D.; Markman, B.; Michael, M.; Underhill, C.; Carlino, M.S.; Jackett, L.; Lum, C.; Scott, C.; Nagrial, A.; et al. Immunotherapy of Ipilimumab and Nivolumab in Patients with Advanced Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Subgroup Analysis of the CA209-538 Clinical Trial for Rare Cancers. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 4454–4459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.P.; Mayerson, E.; Chae, Y.K.; Strosberg, J.; Wang, J.; Konda, B.; Hayward, J.; McLeod, C.M.; Chen, H.X.; Sharon, E.; et al. A phase II basket trial of Dual Anti-CTLA-4 and Anti-PD-1 Blockade in Rare Tumors (DART) SWOG S1609: High-grade neuroendocrine neoplasm cohort. Cancer 2021, 127, 3194–3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halperin, D.M.; Liu, S.; Dasari, A.; Fogelman, D.; Bhosale, P.; Mahvash, A.; Estrella, J.S.; Rubin, L.; Morani, A.C.; Knafl, M.; et al. Assessment of Clinical Response Following Atezolizumab and Bevacizumab Treatment in Patients with Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Nonrandomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2022, 8, 904–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousin, S.; Guégan, J.P.; Palmieri, L.J.; Metges, J.P.; Pernot, S.; Bellera, C.A.; Assenat, E.; Korakis, I.; Cassier, P.A.; Hollebecque, A.; et al. Regorafenib plus avelumab in advanced gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: A phase 2 trial and correlative analysis. Nat. Cancer 2025, 6, 584–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gubbi, S.; Vijayvergia, N.; Yu, J.Q.; Klubo-Gwiezdzinska, J.; Koch, C.A. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy in Neuroendocrine Tumors. Horm. Metab. Res. 2022, 54, 795–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venizelos, A.; Elvebakken, H.; Perren, A.; Nikolaienko, O.; Deng, W.; Lothe, I.M.B.; Couvelard, A.; Hjortland, G.O.; Sundlöv, A.; Svensson, J.; et al. The molecular characteristics of high-grade gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2021, 29, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yellapragada, S.V.; Forsythe, S.D.; Madigan, J.P.; Sadowski, S.M. The Role of the Tumor Microenvironment in Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popa Ilie, I.R.; Georgescu, C.E. Immunotherapy in Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasia. Neuroendocrinology 2023, 113, 262–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maggio, I.; Manuzzi, L.; Lamberti, G.; Ricci, A.D.; Tober, N.; Campana, D. Landscape and Future Perspectives of Immunotherapy in Neuroendocrine Neoplasia. Cancers 2020, 12, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banissi, C.; Ghiringhelli, F.; Chen, L.; Carpentier, A.F. Treg depletion with a low-dose metronomic temozolomide regimen in a rat glioma model. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2009, 58, 1627–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, D.H.; Benner, B.; Wei, L.; Sukrithan, V.; Goyal, A.; Zhou, Y.; Pilcher, C.; Suffren, S.A.; Christenson, G.; Curtis, N.; et al. A Phase II Clinical Trial of Nivolumab and Temozolomide for Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strosberg, J.R.; Koumarianou, A.; Riechelmann, R.; Hernando, J.; Cingarlini, S.; Crona, J.; Al-Toubah, T.E.; Apostolidis, L.; Bergsland, E.K.; Halfdanarson, T.R.; et al. Efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with advanced pancreatic NETs displaying high TMB and MMR alterations following treatment with alkylating agents. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43 (Suppl. 4), 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Ma, Y.; Yu, J.; Sun, Y.; Sun, T.; Shao, Y.; Li, J.; Shen, L.; Lu, M. Favorable response to immunotherapy in a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor with temozolomide-induced high tumor mutational burden. Cancer Commun. 2020, 40, 746–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, J.; Egusa, E.A.; Wang, S.; Badura, M.L.; Lee, F.; Bidkar, A.P.; Zhu, J.; Shenoy, T.; Trepka, K.; Robinson, T.M.; et al. Immunotherapeutic Targeting and PET Imaging of DLL3 in Small-Cell Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancer. Cancer Res. 2023, 83, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Chu, S.Y.; Rashid, R.; Phung, S.; Leung, I.W.; Muchhal, U.S.; Moore, G.L.; Bernett, M.J.; Schubbert, S.; Ardila, C.; et al. Abstract 3633: Anti-SSTR2 × anti-CD3 bispecific antibody induces potent killing of human tumor cells in vitro and in mice, and stimulates target-dependent T cell activation in monkeys: A potential immunotherapy for neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer Res. 2017, 77 (Suppl. 13), 3633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Rayes, B.; Pant, S.; Villalobos, V.; Hendifar, A.; Chow, W.; Konda, B.; Reilley, M.; Benson, A.; Fisher, G.; Starr, J.; et al. Preliminary Safety, PK/PD, and Antitumor Activity of XmAb18087, an SSTR2 x CD3 Bispecific Antibody, in Patients with Advanced Neuroendocrine Tumors. In Proceedings of the North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society, Montreal, QC, Canada, 1–3 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, X.; Yang, P.; Zhang, E.; Gu, J.; Xu, H.; Li, M.; Gao, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, H.; et al. Significantly increased anti-tumor activity of carcinoembryonic antigen-specific chimeric antigen receptor T cells in combination with recombinant human IL-12. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 4753–4765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandriani, B.; Pellè, E.; Mannavola, F.; Palazzo, A.; Marsano, R.M.; Ingravallo, G.; Cazzato, G.; Ramello, M.C.; Porta, C.; Strosberg, J.; et al. Development of anti-somatostatin receptors CAR T cells for treatment of neuroendocrine tumors. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e004854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; He, X.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Y.; Xing, B.; Knowles, A.; Shan, Q.; Miller, S.; Hojnacki, T.; Ma, J.; et al. Potent suppression of neuroendocrine tumors and gastrointestinal cancers by CDH17CAR T cells without toxicity to normal tissues. Nat. Cancer 2022, 3, 581–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Ye, C.; Chen, R.; Li, Q.; Ruan, J. The Landscape and Clinical Application of the Tumor Microenvironment in Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Cancers 2022, 14, 2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazio, N.; La Salvia, A. Precision medicine in gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: Where are we in 2023? Best Prac. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 37, 101794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peddio, A.; Pietroluongo, E.; Lamia, M.R.; Luciano, A.; Caltavituro, A.; Buonaiuto, R.; Pecoraro, G.; De Placido, P.; Palmieri, G.; Bianco, R.; et al. DLL3 as a potential diagnostic and therapeutic target in neuroendocrine neoplasms: A narrative review. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2024, 204, 104524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Bergsland, E.; Aggarwal, R.; Aparicio, A.; Beltran, H.; Crabtree, J.S.; Hann, C.L.; Ibrahim, T.; Byers, L.A.; Sasano, H.; et al. DLL3 as an Emerging Target for the Treatment of Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Oncologist 2022, 27, 940–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, S. Tarlatamab: First Approval. Drugs 2024, 84, 995–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giffin, M.J.; Cooke, K.; Lobenhofer, E.K.; Estrada, J.; Zhan, J.; Deegen, P.; Thomas, M.; Murawsky, C.M.; Werner, J.; Liu, S.; et al. AMG 757, a Half-Life Extended, DLL3-Targeted Bispecific T-Cell Engager, Shows High Potency and Sensitivity in Preclinical Models of Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 1526–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.L.; Dy, G.K.; Mamdani, H.; Dowlati, A.; Schoenfeld, A.J.; Pacheco, J.M.; Sanborn, R.E.; Menon, S.P.; Santiago, L.; Yaron, Y.; et al. Interim results of an ongoing phase 1/2a study of HPN328, a tri-specific, half-life extended, DLL3-targeting, T-cell engager, in patients with small cell lung cancer and other neuroendocrine cancers. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40 (Suppl. 16), 8566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Qian, Z.R.; Zhang, S.; Li, W.; Masugi, Y.; Li, T.; Chan, J.A.; Yang, J.; Da Silva, A.; Gu, M.; et al. Cell Cycle Protein Expression in Neuroendocrine Tumors: Association of CDK4/CDK6, CCND1, and Phosphorylated Retinoblastoma Protein with Proliferative Index. Pancreas 2017, 46, 1347–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grande, E.; Teulé, A.; Alonso-Gordoa, T.; Jiménez-Fonseca, P.; Benavent, M.; Capdevila, J.; Custodio, A.; Vera, R.; Munarriz, J.; La Casta, A.; et al. The PALBONET Trial: A Phase II Study of Palbociclib in Metastatic Grade 1 and 2 Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors (GETNE-1407). Oncologist 2020, 25, 745-e1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, L.H.; Contractor, T.; Clausen, R.; Klimstra, D.S.; Du, Y.C.; Allen, P.J.; Brennan, M.F.; Levine, A.J.; Harris, C.R. Attenuation of the retinoblastoma pathway in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors due to increased cdk4/cdk6. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 4612–4620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, N.; Zheng, Y.; Hauser, H.; Chou, J.; Rafailov, J.; Bou-Ayache, J.; Sawan, P.; Chaft, J.; Chan, J.; Perez, K.; et al. Ribociclib and everolimus in well-differentiated foregut neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2021, 28, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, S.E. Epigenetic Therapies for Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 650–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glozak, M.A.; Seto, E. Histone deacetylases and cancer. Oncogene 2007, 26, 5420–5432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gennaro, E.; Bruzzese, F.; Caraglia, M.; Abruzzese, A.; Budillon, A. Acetylation of proteins as novel target for antitumor therapy: Review article. Amino Acids 2004, 26, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barneda-Zahonero, B.; Parra, M. Histone deacetylases and cancer. Mol. Oncol. 2012, 6, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamison, J.K.; Zhou, M.; Gelmann, E.P.; Luk, L.; Bates, S.E.; Califano, A.; Fojo, T. Entinostat in patients with relapsed or refractory abdominal neuroendocrine tumors. Oncologist 2024, 29, 817-e1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safari, M.; Scotto, L.; Litman, T.; Petrukhin, L.A.; Zhu, H.; Shen, M.; Robey, R.W.; Hall, M.D.; Fojo, T.; Bates, S.E. Novel Therapeutic Strategies Exploiting the Unique Properties of Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Cancers 2023, 15, 4960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesario, A.; D’Oria, M.; Calvani, R.; Picca, A.; Pietragalla, A.; Lorusso, D.; Daniele, G.; Lohmeyer, F.M.; Boldrini, L.; Valentini, V.; et al. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Managing Multimorbidity and Cancer. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.T.; Chen, L.; Yue, W.W.; Xu, H.X. Digital Technology-Based Telemedicine for the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 646506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schinköthe, T. Individualized eHealth Support for Oncological Therapy Management. Breast Care 2019, 14, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albino de Queiroz, D.; André da Costa, C.; Aparecida Isquierdo Fonseca de Queiroz, E.; Folchini da Silveira, E.; da Rosa Righi, R. Internet of Things in active cancer Treatment: A systematic review. J. Biomed. Inform. 2021, 118, 103814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.H.; Lee, J.I.; Lee, J.Y.; Cheong, I.Y.; Hwang, J.H.; Seo, S.I.; Lee, K.H.; Yoo, J.S.; Chung, S.H.; So, Y. Internet of things-based lifestyle intervention for prostate cancer patients on androgen deprivation therapy: A prospective, multicenter, randomized trial. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2021, 11, 5496–5507. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, J.C.; Kim, H.R.; Song, S.; Kwon, H.; Ji, W.; Choi, C.M. Mobile Phone App-Based Pulmonary Rehabilitation for Chemotherapy-Treated Patients with Advanced Lung Cancer: Pilot Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2019, 7, e11094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jourquin, J.; Reffey, S.B.; Jernigan, C.; Levy, M.; Zinser, G.; Sabelko, K.; Pietenpol, J.; Sledge, G., Jr.; Susan, G. Komen Big Data for Breast Cancer Initiative: How Patient Advocacy Organizations Can Facilitate Using Big Data to Improve Patient Outcomes. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2019, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sguanci, M.; Palomares, S.M.; Cangelosi, G.; Petrelli, F.; Sandri, E.; Ferrara, G.; Mancin, S. Artificial Intelligence in the Management of Malnutrition in Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. Adv. Nutr. 2025, 16, 100438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, H.; Nakayama, K.I. Artificial intelligence in oncology. Cancer Sci. 2020, 111, 1452–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chua, I.S.; Gaziel-Yablowitz, M.; Korach, Z.T.; Kehl, K.L.; Levitan, N.A.; Arriaga, Y.E.; Jackson, G.P.; Bates, D.W.; Hassett, M. Artificial intelligence in oncology: Path to implementation. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 4138–4149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhinder, B.; Gilvary, C.; Madhukar, N.S.; Elemento, O. Artificial Intelligence in Cancer Research and Precision Medicine. Cancer Discov. 2021, 11, 900–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Freixinos, V.; Thawer, A.; Capdevila, J.; Ferone, D.; Singh, S. Advanced Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Which Systemic Treatment Should I Start With? Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2021, 23, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panzuto, F.; Lamarca, A.; Fazio, N. Comparative analysis of international guidelines on the management of advanced non-functioning well-differentiated pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2024, 129, 102803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kos-Kudła, B.; Rosiek, V.; Borowska, M.; Bednarczuk, T.; Bolanowski, M.; Chmielik, E.; Ćwikła, J.B.; Foltyn, W.; Gisterek, I.; Handkiewicz-Junak, D.; et al. Pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms—Update of the diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines (recommended by the Polish Network of Neuroendocrine Tumours) [Nowotwory neuroendokrynne trzustki—Uaktualnione zasady diagnostyki i leczenia (rekomendowane przez Polską Sieć Guzów Neuroendokrynych)]. Endokrynol. Pol. 2022, 73, 491–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijioka, S.; Morizane, C.; Ikeda, M.; Ishii, H.; Okusaka, T.; Furuse, J. Current status of medical treatment for gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms and future perspectives. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 51, 1185–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melhorn, P.; Mazal, P.; Wolff, L.; Kretschmer-Chott, E.; Raderer, M.; Kiesewetter, B. From biology to clinical practice: Antiproliferative effects of somatostatin analogs in neuroendocrine neoplasms. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2024, 16, 17588359241240316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halfdanarson, T.R.; Strosberg, J.R.; Tang, L.; Bellizzi, A.M.; Bergsland, E.K.; O’Dorisio, T.M.; Halperin, D.M.; Fishbein, L.; Eads, J.; Hope, T.A.; et al. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society Consensus Guidelines for Surveillance and Medical Management of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Pancreas 2020, 49, 863–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Trial Identifier | Study Phase | Therapeutic Regimen | Type of Therapy or Target | Patient Population | Study Start |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT05058651 | 2/3 | EP + atezolizumab vs. EP | Chemotherapy + monoclonal antibody for PD-L1 | Treatment-naïve, advanced, or metastatic extrapulmonary NEC | 28 June 2022 |

| NCT05746208 | 2 | Lenvatinib + Pembrolizumab | Multi-receptor TKI for VEGFR + monoclonal antibody for PD-1 | Occurring de novo or great progressive advanced or unresectable WD G3 NET | 17 July 2023 |

| NCT05627427 | 2 | Surufatinib + Sintilimab | Small-molecule TKI for VEGFR, FGFR1 + monoclonal antibody for PD-1 | Refractory, metastatic, or advanced NET G3, NEC PC | 1 July 2022 |

| NCT06889493 | 2 | SVV-001+ Nivolumab + Ipilimumab | Oncolytic virus + monoclonal antibody for PD-1 + monoclonal antibody for CTLA4 | Advanced, metastatic, or progressed on at least one line of therapy WD NET G3, NEC | 19 May 2025 |

| NCT03591731 | 2 | Nivolumab +/− Ipilimumab | Monoclonal antibody for PD-1+ monoclonal antibody for CTLA4 | Refractory, advanced, or metastatic NEC | 2 January 2019 |

| NCT06232564 | 2 | Etoposide–carboplatin + Pembrolizumab + Lenvatinib | Chemotherapy + monoclonal antibody for PD-1 + multi-receptor TKI for VEGFR | Metastatic, treatment-naïve for metastatic setting HG-NET | 8 July 2024 |

| NCT05015621 | 3 | Surufatinib + Toripalimab vs. FOLFIRI | Small-molecule TKI for VEGFR, FGFR1 + monoclonal antibody for PD-1 | Advanced or metastatic, progressed on platinum-based 1st-line chemotherapy NEC | 18 September 2021 |

| NCT04525638 | 2 | 177Lu-DOTATATE + Nivolumab | PRRT + monoclonal antibody for PD-1 | Advanced or metastatic, progressed on at least one line of therapy or treatment-naïve WD NET G3, NEC | 29 June 2021 |

| NCT03457948 | 2 | Pembrolizumab + PRRT/arterial embolization/Yttrium-90 microsphere radioembolization | Monoclonal antibody for PD-1+ PRRT + arterial embolization | NET with liver metastases | 27 August 2018 |

| Trial Identifier | Study Phase | Therapeutic Regimen | Type of Therapy or Target | Patient Population | Study Start |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT06788938 | 2 | Tarlatamab | Bispecific T-cell engager | DLL3-Expressing Tumors Including NEN | 21 March 2025 |

| NCT06816394 | 2 | Tarlatamab | Bispecific T-cell engager | EPSCC or NEC | 15 May 2025 |

| NCT04429087 | 1 | BI 764532 | Antibody-like molecule (DLL3/CD3 bispecific) | SCLC and NEN Expressing DLL3 | 23 September 2020 |

| NCT06132113 | 1 | BI 764532 | Antibody-like molecule (DLL3/CD3 bispecific) | NEC | 22 January 2024 |

| NCT04471727 | 1,2 | HPN 328 | Trispecific T-cell engager | Advanced Cancers Expressing DLL3 | 14 December 2020 |

| NCT05652686 | 1,2 | Peluntamig | Bispecific antibody | NEC Expressing DLL3 | 5 September 2023 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Romanowicz, A.; Fudalej, M.; Asendrych-Woźniak, A.; Badowska-Kozakiewicz, A.; Nurzyński, P.; Deptała, A. New Treatment Options for Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Narrative Review. Cancers 2025, 17, 3837. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233837

Romanowicz A, Fudalej M, Asendrych-Woźniak A, Badowska-Kozakiewicz A, Nurzyński P, Deptała A. New Treatment Options for Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Narrative Review. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3837. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233837

Chicago/Turabian StyleRomanowicz, Agnieszka, Marta Fudalej, Alicja Asendrych-Woźniak, Anna Badowska-Kozakiewicz, Paweł Nurzyński, and Andrzej Deptała. 2025. "New Treatment Options for Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Narrative Review" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3837. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233837

APA StyleRomanowicz, A., Fudalej, M., Asendrych-Woźniak, A., Badowska-Kozakiewicz, A., Nurzyński, P., & Deptała, A. (2025). New Treatment Options for Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Narrative Review. Cancers, 17(23), 3837. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233837