Robotic Surgery for Gastrointestinal Malignancies—A Review of How Far Have We Come in Pancreatic, Gastric, Liver, and Colorectal Cancer Surgery

Simple Summary

Abstract

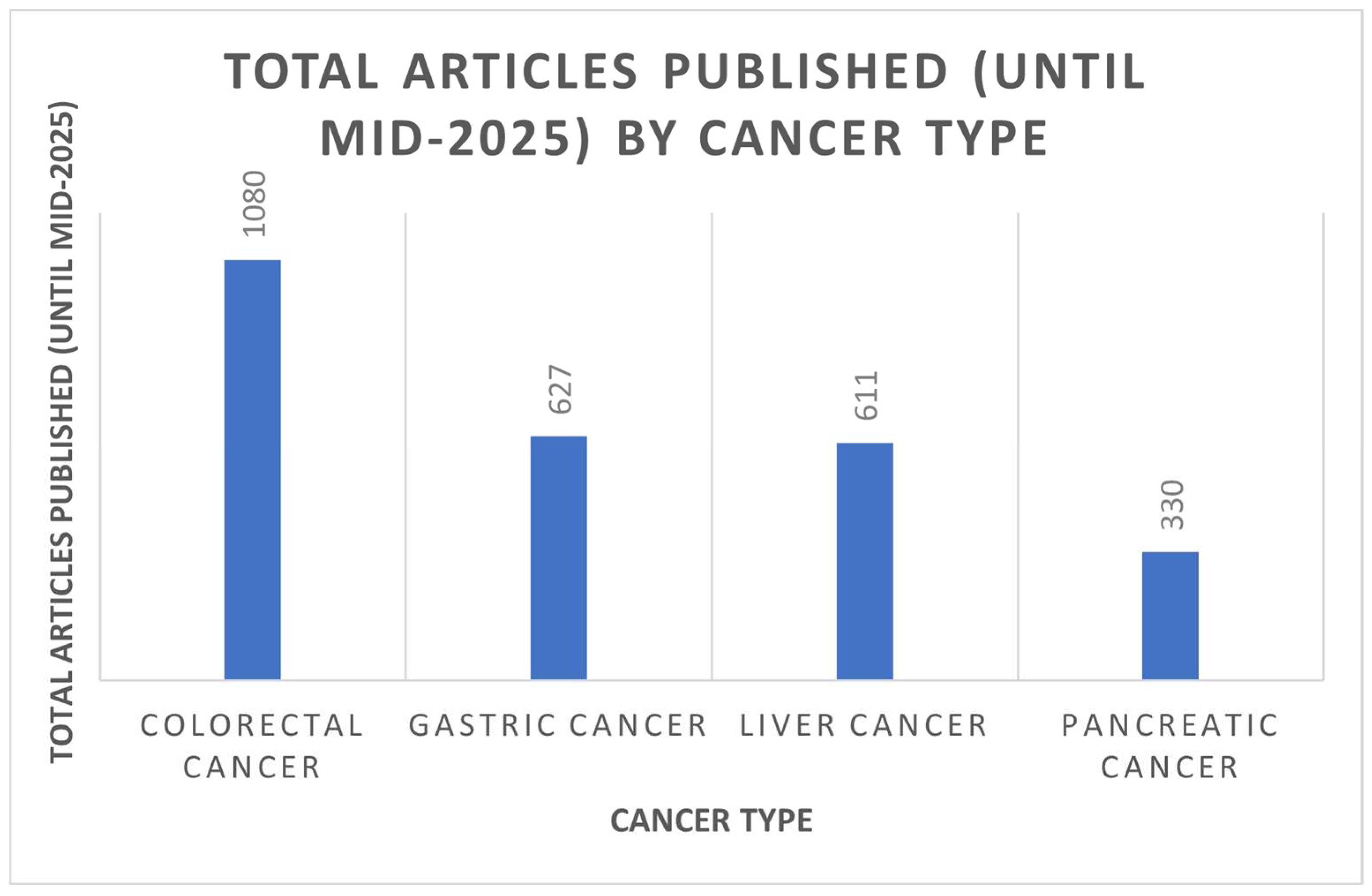

1. Introduction

2. Robotic Surgery for Pancreatic Cancer

2.1. Advantages of Robotic Surgery for Pancreatic Cancer

2.2. Disadvantages of Robotic Surgery for Pancreatic Cancer

2.3. Quality of the Data

3. Robotic Surgery for Gastric Cancer

3.1. Advantages of Robotic Surgery for Gastric Cancer

3.2. Disadvantages of Robotic Surgery for Gastric Cancer

3.3. Quality of the Data

4. Robotic Surgery for Liver Cancer

4.1. Advantages of Robotic Surgery for Liver Cancer

4.2. Disadvantages of Robotic Surgery for Liver Cancer

4.3. Quality of the Data

5. Robotic Surgery for Colorectal Cancer

5.1. Advantages of Robotic Surgery for Colorectal Cancer

5.2. Disadvantages of Robotic Surgery for Colorectal Cancer

5.3. Quality of the Data

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ghezzi, T.L.; Corleta, O.C. 30 Years of Robotic Surgery. World J. Surg. 2016, 40, 2550–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefor, A.K. Robotic and laparoscopic surgery of the pancreas: An historical review. BMC Biomed. Eng. 2019, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korrel, M.; Jones, L.R.; van Hilst, J.; Balzano, G.; Björnsson, B.; Boggi, U.; Bratlie, S.O.; Busch, O.R.; Butturini, G.; Capretti, G.; et al. Minimally invasive versus open distal pancreatectomy for resectable pancreatic cancer (DIPLOMA): An international randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet Reg. Health–Eur. 2023, 31, 100673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Rooij, T.; van Hilst, J.; van Santvoort, H.; Boerma, D.; van den Boezem, P.; Daams, F.; van Dam, R.; Dejong, C.; van Duyn, E.; Dijkgraaf, M.; et al. Minimally Invasive Versus Open Distal Pancreatectomy (LEOPARD): A Multicenter Patient-blinded Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann. Surg. 2019, 269, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klotz, R.; Mihaljevic, A.L.; Kulu, Y.; Sander, A.; Klose, C.; Behnisch, R.; Joos, M.C.; Kalkum, E.; Nickel, F.; Knebel, P.; et al. Robotic versus open partial pancreatoduodenectomy (EUROPA): A randomised controlled stage 2b trial. Lancet Reg. Health–Eur. 2024, 39, 100864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Zheng, C.H.; Xu, B.B.; Xie, J.W.; Wang, J.B.; Lin, J.X.; Chen, Q.Y.; Cao, L.L.; Lin, M.; Tu, R.H.; et al. Assessment of Robotic Versus Laparoscopic Distal Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann. Surg. 2021, 273, 858–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.R.; Cao, S.G.; Meng, C.; Liu, X.D.; Li, Z.Q.; Tian, Y.L.; Xu, J.F.; Sun, Y.Q.; Liu, G.; Zhang, X.Q.; et al. Patient-reported outcomes of locally advanced gastric cancer undergoing robotic versus laparoscopic gastrectomy: A randomized controlled study. Chin. J. Surg. 2023, 62, 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Xu, B.B.; Zheng, H.L.; Li, P.; Xie, J.W.; Wang, J.B.; Lin, J.X.; Chen, Q.Y.; Cao, L.L.; Lin, M.; et al. Robotic versus laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for resectable gastric cancer: A randomized phase 2 trial. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojima, T.; Nakamura, M.; Hayata, K.; Kitadani, J.; Katsuda, M.; Takeuchi, A.; Tominaga, S.; Nakai, T.; Nakamori, M.; Ohi, M.; et al. Short-term Outcomes of Robotic Gastrectomy vs Laparoscopic Gastrectomy for Patients with Gastric Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg. 2021, 156, 954–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birgin, E.; Heibel, M.; Hetjens, S.; Rasbach, E.; Reissfelder, C.; Téoule, P.; Rahbari, N.N. Robotic versus laparoscopic hepatectomy for liver malignancies (ROC'N'ROLL): A single-centre, randomised, controlled, single-blinded clinical trial. Lancet Reg. Health–Eur. 2024, 43, 100972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S.; Kang, H.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, H.J.; Woo, I.T.; Park, I.K.; Choi, G.S. Long-term oncologic after robotic versus laparoscopic right colectomy: A prospective randomized study. Surg. Endosc. 2019, 33, 2975–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez Rodríguez, R.M.; Pavón, J.M.D.; de La Portilla de Juan, F.; Sillero, E.P.; Dussort, J.M.H.C.; Padillo, J. Prospective randomised study: Robotic-assisted versus conventional laparoscopic surgery in colorectal cancer resection. Cir. Esp. 2011, 89, 432–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayne, D.; Pigazzi, A.; Marshall, H.; Croft, J.; Corrigan, N.; Copeland, J.; Quirke, P.; West, N.; Rautio, T.; Thomassen, N.; et al. Effect of Robotic-Assisted vs Conventional Laparoscopic Surgery on Risk of Conversion to Open Laparotomy Among Patients Undergoing Resection for Rectal Cancer: The ROLARR Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2017, 318, 1569–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Yuan, W.; Li, T.; Tang, B.; Jia, B.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, R.; Zhang, C.; Cheng, L.; et al. Robotic versus laparoscopic surgery for middle and low rectal cancer (REAL): Short-term outcomes of a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 7, 991–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Yuan, W.; Li, T.; Tang, B.; Jia, B.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, R.; Zhang, C.; Cheng, L.; et al. Robotic vs Laparoscopic Surgery for Middle and Low Rectal Cancer: The REAL Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2025, 334, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patriti, A.; Ceccarelli, G.; Bartoli, A.; Spaziani, A.; Biancafarina, A.; Casciola, L. Short- and medium-term outcome of robot-assisted and traditional laparoscopic rectal resection. J. Soc. Laparoendosc. Surg. 2009, 13, 176–183. [Google Scholar]

- Baik, S.H.; Ko, Y.T.; Kang, C.M.; Lee, W.J.; Kim, N.K.; Sohn, S.K.; Chi, H.S.; Cho, C.H. Robotic tumor-specific mesorectal excision of rectal cancer: Short-term outcome of a pilot randomized trial. Surg. Endosc. 2008, 22, 1601–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolstrup, R.; Funder, J.A.; Lundbech, L.; Thomassen, N.; Iversen, L.H. Perioperative pain after robot-assisted versus laparoscopic rectal resection. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2018, 33, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Park, S.C.; Park, J.W.; Chang, H.J.; Kim, D.Y.; Nam, B.H.; Sohn, D.K.; Oh, J.H. Robot-assisted Versus Laparoscopic Surgery for Rectal Cancer: A Phase II Open Label Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann. Surg. 2018, 267, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debakey, Y.; Zaghloul, A.; Farag, A.; Mahmoud, A.; Elattar, I. Robotic-Assisted versus Conventional Laparoscopic Approach for Rectal Cancer Surgery, First Egyptian Academic Center Experience, RCT. Minim. Invasive Surg. 2018, 2018, 5836562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S.; Lee, S.M.; Choi, G.S.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, H.J.; Song, S.H.; Min, B.S.; Kim, N.K.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, K.Y. Comparison of Laparoscopic Versus Robot-Assisted Surgery for Rectal Cancers: The COLRAR Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann. Surg. 2023, 278, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarivate, Web of Science. Available online: https://clarivate.com/academia-government/scientific-and-academic-research/research-discovery-and-referencing/web-of-science/ (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Khachfe, H.H.; Habib, J.R.; Harthi, S.A.; Suhool, A.; Hallal, A.H.; Jamali, F.R. Robotic pancreas surgery: An overview of history and update on technique, outcomes, and financials. J. Robot. Surg. 2022, 16, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, P.; Lewis, A.; Thornblade, L.W.; Maker, A.V.; Fong, Y.; Melstrom, L.G. Robotic pancreatectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: Evolving trends in patient selection and practice patterns across a decade. HPB 2025, 27, 1223–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, F.; Bonaduce, I.; De Ruvo, N.; Cautero, N.; Gelmini, R. Short-term and long term morbidity in robotic pancreatic surgery: A systematic review. Gland. Surg. 2021, 10, 1767–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giulianotti, P.C.; Mangano, A.; Bustos, R.E.; Gheza, F.; Fernandes, E.; Masrur, M.A.; Gangemi, A.; Bianco, F.M. Operative technique in robotic pancreaticoduodenectomy (RPD) at University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC): 17 steps standardized technique: Lessons learned since the first worldwide RPD performed in the year 2001. Surg. Endosc. 2018, 32, 4329–4336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, S.B.; Rojas, A.E.; Hogg, M.E. Robotic pancreas surgery for pancreatic cancer. Int. J. Surg. 2024, 110, 6100–6110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PancreasGroup. Pancreatic surgery outcomes: Multicentre prospective snapshot study in 67 countries. Br. J. Surg. 2024, 111, znad330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamarajah, S.K.; Bundred, J.; Marc, O.S.; Jiao, L.R.; Manas, D.; Hilal, M.A.; White, S.A. Robotic versus conventional laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 46, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.H.; Qin, Y.F.; Yu, D.D.; Li, X.; Zhao, Y.M.; Kong, D.J.; Jin, W.; Wang, H. Meta-analysis of short-term outcomes comparing robot-assisted and laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy. J. Comp. Eff. Res. 2020, 9, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y.; Chen, M.; Gemenetzis, G.; Shi, Y.; Ying, X.; Deng, X.; Peng, C.; Jin, J.; Shen, B. Robotic-assisted versus open total pancreatectomy: A propensity score-matched study. Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 2020, 9, 760–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Dong, X.; Felsenreich, D.M.; Gogna, S.; Rojas, A.; Zhang, E.; Dong, M.; Azim, A.; Gachabayov, M. Robotic pancreaticoduodenectomy provides better histopathological outcomes as compared to its open counterpart: A meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Hilal, M.A.; Wakabayashi, G.; Han, H.S.; Palanivelu, C.; Boggi, U.; Hackert, T.; Kim, H.J.; Wang, X.Y.; Hu, M.G.; et al. International experts consensus guidelines on robotic liver resection in 2023. World J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 29, 4815–4830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daouadi, M.; Zureikat, A.H.; Zenati, M.S.; Choudry, H.; Tsung, A.; Bartlett, D.L.; Hughes, S.J.; Lee, K.K.; Moser, A.J.; Zeh, H.J. Robot-assisted minimally invasive distal pancreatectomy is superior to the laparoscopic technique. Ann. Surg. 2013, 257, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konstantinidis, I.T.; Jutric, Z.; Eng, O.S.; Warner, S.G.; Melstrom, L.G.; Fong, Y.; Lee, B.; Singh, G. Robotic total pancreatectomy with splenectomy: Technique and outcomes. Surg. Endosc. 2018, 32, 3691–3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Hilst, J.; de Rooij, T.; Bosscha, K.; Brinkman, D.J.; van Dieren, S.; Dijkgraaf, M.G.; Gerhards, M.F.; de Hingh, I.H.; Karsten, T.M.; Lips, D.J.; et al. Laparoscopic versus open pancreatoduodenectomy for pancreatic or periampullary tumours (LEOPARD-2): A multicentre, patient-blinded, randomised controlled phase 2/3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 4, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, V.; Pakataridis, P.; Marchese, T.; Ferrari, C.; Chelmis, F.; Sorotou, I.N.; Gianniou, M.A.; Dimova, A.; Tcholakov, O.; Ielpo, B. Comparative Analysis of Open, Laparoscopic, and Robotic Pancreaticoduodenectomy: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Medicina 2025, 61, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashizume, M.; Sugimachi, K. Robot-assisted gastric surgery. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2003, 83, 1429–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibasaki, S.; Suda, K.; Hisamori, S.; Obama, K.; Terashima, M.; Uyama, I. Robotic gastrectomy for gastric cancer: Systematic review and future directions. Gastric Cancer 2023, 26, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baral, S.; Arawker, M.H.; Sun, Q.; Jiang, M.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Ali, M.; Wang, D. Robotic Versus Laparoscopic Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer: A Mega Meta-Analysis. Front. Surg. 2022, 9, 896076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zizzo, M.; Zanelli, M.; Sanguedolce, F.; Torricelli, F.; Morini, A.; Tumiati, D.; Mereu, F.; Zuliani, A.L.; Palicelli, A.; Ascani, S.; et al. Robotic versus Laparoscopic Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer: An Updated Systematic Review. Medicina 2022, 58, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.F.; Wang, G.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.X.; Zhao, K.; Tang, X.F.; Jiang, Z.W. Robotic Versus Laparoscopic Gastrectomy for Locally Advanced Gastric Cancer. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. Percutaneous Tech. 2017, 27, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Jiang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, K.; Feng, X.; Li, J. Assessing the safety and efficacy of full robotic gastrectomy with intracorporeal robot-sewn anastomosis for gastric cancer: A randomized clinical trial. J. Surg. Oncol. 2016, 113, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marano, L.; Cwalinski, T.; Girnyi, S.; Skokowski, J.; Goyal, A.; Malerba, S.; Prete, F.P.; Mocarski, P.; Kania, M.K.; Swierblewski, M.; et al. Evaluating the Role of Robotic Surgery Gastric Cancer Treatment: A Comprehensive Review by the Robotic Global Surgical Society (TROGSS) and European Federation International Society for Digestive Surgery (EFISDS) Joint Working Group. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.; Liu, H.D.; Yang, K.; Chen, Z.H.; Zhang, Y.X.; Hu, J.K. Effectiveness and safety of robotic gastrectomy versus laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer: A meta-analysis of 12,401 gastric cancer patients. Updates Surg. 2022, 74, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.Y.; Zhong, Q.; Liu, Z.Y.; Li, P.; Wang, J.B.; Lin, J.X.; Lu, J.; Cao, L.L.; Lin, M.; Tu, R.H.; et al. Surgical Outcomes, Technical Performance, and Surgery Burden of Robotic Total Gastrectomy for Locally Advanced Gastric Cancer: A Prospective Study. Ann. Surg. 2022, 276, e434–e443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Qian, F.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, F.; Wang, X.; Li, P.; Liu, J.; Wen, Y.; Feng, Q.; et al. A comparative study on perioperative outcomes between robotic versus laparoscopic D2 total gastrectomy. Int. J. Surg. 2022, 102, 106636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryska, M.; Fronek, J.; Rudis, J.; Jurenka, B.; Langer, D.; Pudil, J. Manual and robotic laparoscopic liver resection. Two case-reviews. Rozhl. Chir. 2006, 85, 511–516. [Google Scholar]

- Pilz da Cunha, G.; Hoogteijling, T.J.; Besselink, M.G.; Alzoubi, M.N.; Swijnenburg, R.J.; Hilal, M.A. Robotic versus laparoscopic liver resection: A systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. Int. J. Surg. 2025, 111, 5549–5571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Sandro, S.; Centonze, L.; Ratti, F.; Russolillo, N.; Conci, S.; Gringeri, E.; Ardito, F.; Colasanti, M.; Sposito, C.; De Carlis, R.; et al. Robotic vs laparoscopic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: Multicentric propensity-score matched analysis of surgical and oncologic outcomes in 647 patients. Updates Surg. 2025, 77, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.Q.; Mao, Y.L.; Lv, T.R.; Liu, F.; Li, F.Y. A meta-analysis between robotic hepatectomy and conventional open hepatectomy. J. Robot. Surg. 2024, 18, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Zhao, X.; Xie, Q.; Jiang, K.; Mao, T.; Yang, M.; Wu, H. Comparison of short-term outcomes between robotic and laparoscopic liver resection: A meta-analysis of propensity score-matched studies. Int. J. Surg. 2024, 110, 1126–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Benedetto, F.; Magistri, P.; Di Sandro, S.; Sposito, C.; Oberkofler, C.; Brandon, E.; Samstein, B.; Guidetti, C.; Papageorgiou, A.; Frassoni, S.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Robotic vs Open Liver Resection for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. JAMA Surg. 2023, 158, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willis, F.; Amati, A.L.; Reichert, M.; Hecker, A.; Vilz, T.O.; Kalff, J.C.; Willis, S.; Kröplin, M.A. Current Evidence in Robotic Colorectal Surgery. Cancers 2025, 17, 2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrut, R.L.; Cote, A.; Caus, V.A.; Maghiar, A.M. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Laparoscopic versus Robotic-Assisted Surgery for Colon Cancer: Efficacy, Safety, and Outcomes-A Focus on Studies from 2020–2024. Cancers 2024, 16, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.; Meyer, E.; Meurette, G.; Liot, E.; Toso, C.; Ris, F. Robotic versus laparoscopic right hemicolectomy: A systematic review of the evidence. J. Robot. Surg. 2024, 18, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tschann, P.; Szeverinski, P.; Weigl, M.P.; Rauch, S.; Lechner, D.; Adler, S.; Girotti, P.N.C.; Clemens, P.; Tschann, V.; Presl, J.; et al. Short- and Long-Term Outcome of Laparoscopic- versus Robotic-Assisted Right Colectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.C.; Zhao, S.; Chen, W.; Wu, J.X. Robotic versus laparoscopic right colectomy for colon cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Videosurg. Other Miniinvasive Tech. 2023, 18, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rein, L.K.L.; Dohrn, N.; Gögenur, I.; Klein, M.F. Robotic versus laparoscopic approach for left-sided colon cancer: A nationwide cohort study. Color. Dis. 2023, 25, 2366–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solaini, L.; Bocchino, A.; Avanzolini, A.; Annunziata, D.; Cavaliere, D.; Ercolani, G. Robotic versus laparoscopic left colectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2022, 37, 1497–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajibandeh, S.; Mankotia, R.; Akingboye, A.; Peravali, R. Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials comparing intracorporeal versus extracorporeal anastomosis in laparoscopic right hemicolectomy: Upgrading the level of evidence. Updates Surg. 2021, 73, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.H.; Yan, P.J.; Hu, D.P.; Jin, P.H.; Lv, Y.C.; Liu, R.; Yang, X.F.; Yang, K.H.; Guo, T.K. Short-Term Outcomes of Robotic versus Laparoscopic Total Mesorectal Excision for Rectal Cancer: A Cohort Study. Am. Surg. 2019, 85, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhama, A.R.; Obias, V.; Welch, K.B.; Vandewarker, J.F.; Cleary, R.K. A comparison of laparoscopic and robotic colorectal surgery outcomes using the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) database. Surg. Endosc. 2016, 30, 1576–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirkin, K.A.; Kulaylat, A.S.; Hollenbeak, C.S.; Messaris, E. Robotic versus laparoscopic colectomy for stage I-III colon cancer: Oncologic and long-term survival outcomes. Surg. Endosc. 2018, 32, 2894–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, J.; Cao, H.; Panteleimonitis, S.; Khan, J.; Parvaiz, A. Robotic vs laparoscopic rectal surgery in high-risk patients. Color. Dis. 2017, 19, 1092–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mégevand, J.L.; Lillo, E.; Amboldi, M.; Lenisa, L.; Ambrosi, A.; Rusconi, A. TME for rectal cancer: Consecutive 70 patients treated with laparoscopic and robotic technique-cumulative experience in a single centre. Updates Surg. 2019, 71, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, X.; Liu, X. Robotic Surgery in Rectal Cancer: Potential, Challenges, and Opportunities. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2022, 23, 961–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otukoya, E.Z.; Amiri, A.; Alimohammadi, E. Surgeon well-being: A systematic review of stressors, mental health, and resilience. BMC Surg. 2025, 25, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norasi, H.; Hallbeck, M.S.; Elli, E.F.; Tollefson, M.K.; Harold, K.L.; Pak, R. Impact of preferred surgical modality on surgeon wellness: A survey of workload, physical pain/discomfort, and neuromusculoskeletal disorders. Surg. Endosc. 2023, 37, 9244–9254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas Burbano, J.C.; Ruiz, N.I.; Burbano, G.A.R.; Inca, J.S.G.; Lezama, C.A.A.; Gonzalez, M.S. Robot-Assisted Surgery: Current Applications and Future Trends in General Surgery. Cureus 2025, 17, e82318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Trial Name | Year Published | Cancer Type | Comparison Groups | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIPLOMA [3] | 2023 | Pancreatic (Distal) | Minimally Invasive vs. Open |

|

| LEOPARD [4] | 2019 | Pancreatic (Distal) | Minimally Invasive vs. Open |

|

| EUROPA [5] | 2024 | Pancreatic (PD) | Robotic vs. Open |

|

| Lu et al. [8] | 2021, 2024 | Gastric (Distal) | Robotic vs. Laparoscopic |

|

| Ojima et al. [9] | 2021 | Gastric | Robotic vs. Laparoscopic |

|

| ROC’N’ROLL [10] | 2024 | Liver | Robotic vs. Laparoscopic |

|

| ROLARR [13] | 2017 | Rectal | Robotic vs. Laparoscopic |

|

| REAL [14,15] | 2022, 2025 | Rectal (Mid/Low) | Robotic vs. Laparoscopic |

|

| Outcome Metric | Robotic Approach | Laparoscopic/Open Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Lymph Node Yield (Pancreatic) | 13–20 | 9–15 |

| Lymph Node Yield (Gastric) | 34.5 | 26.6 |

| Lymph Node Yield (Colorectal) | 27 | 24 |

| R0 Resection Rate (Pancreatic) | 84.4–95% | 80.1–83% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Weksler, Y.; Lifshitz, G.; Avital, S.; Rudnicki, Y. Robotic Surgery for Gastrointestinal Malignancies—A Review of How Far Have We Come in Pancreatic, Gastric, Liver, and Colorectal Cancer Surgery. Cancers 2025, 17, 3802. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233802

Weksler Y, Lifshitz G, Avital S, Rudnicki Y. Robotic Surgery for Gastrointestinal Malignancies—A Review of How Far Have We Come in Pancreatic, Gastric, Liver, and Colorectal Cancer Surgery. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3802. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233802

Chicago/Turabian StyleWeksler, Yael, Guy Lifshitz, Shmuel Avital, and Yaron Rudnicki. 2025. "Robotic Surgery for Gastrointestinal Malignancies—A Review of How Far Have We Come in Pancreatic, Gastric, Liver, and Colorectal Cancer Surgery" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3802. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233802

APA StyleWeksler, Y., Lifshitz, G., Avital, S., & Rudnicki, Y. (2025). Robotic Surgery for Gastrointestinal Malignancies—A Review of How Far Have We Come in Pancreatic, Gastric, Liver, and Colorectal Cancer Surgery. Cancers, 17(23), 3802. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233802