Quality and Dosimetric Accuracy of Linac-Based Single-Isocenter Treatment Plans for Four to Eighteen Brain Metastases

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Selection

2.2. Treatment Planning

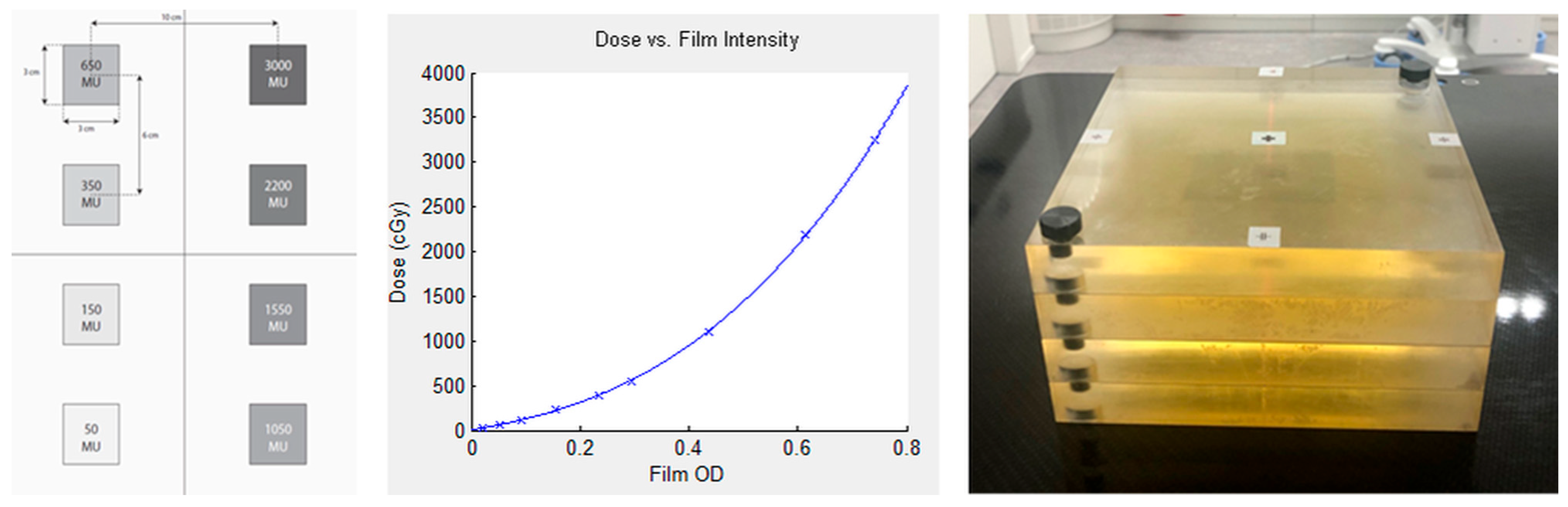

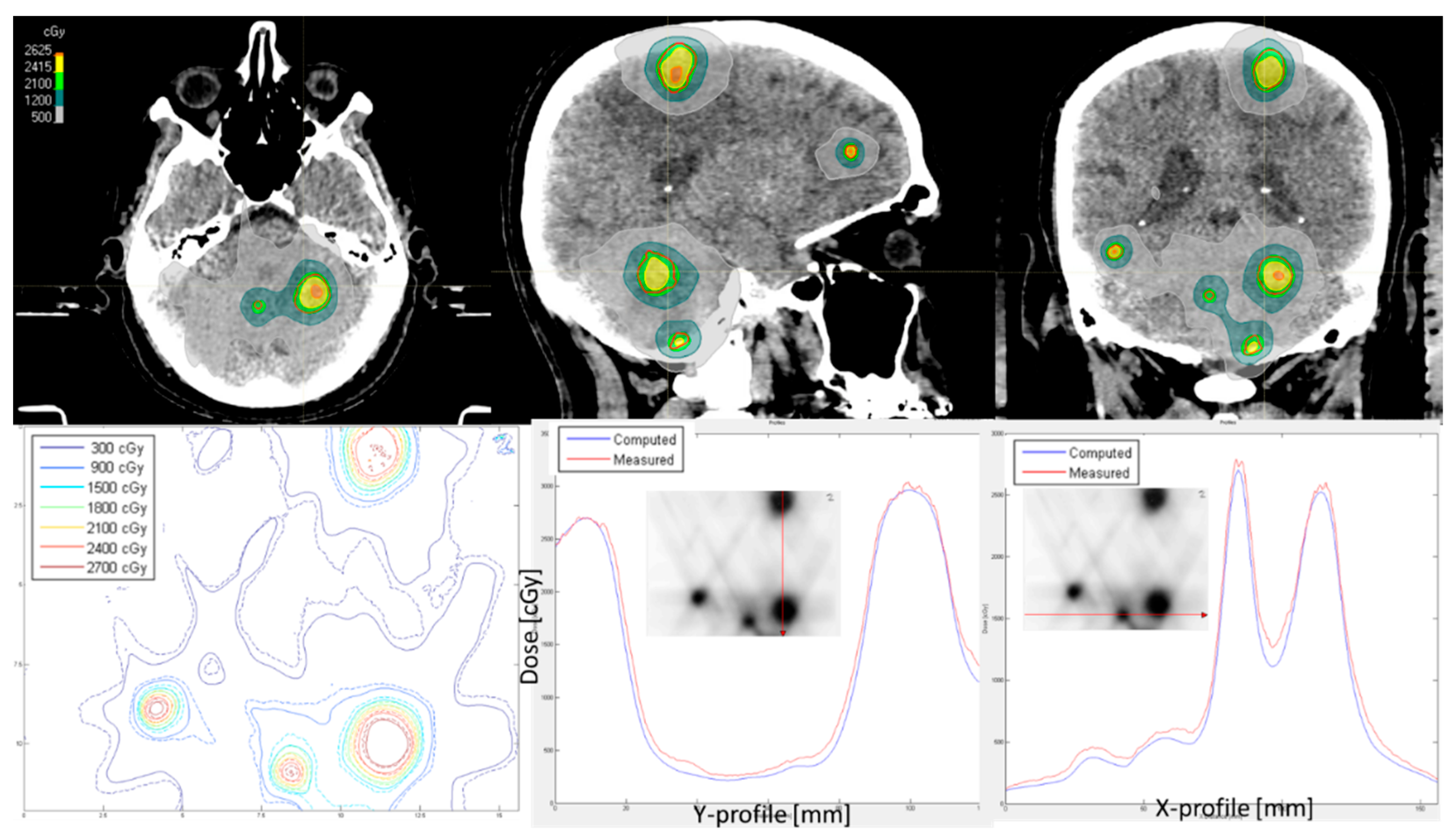

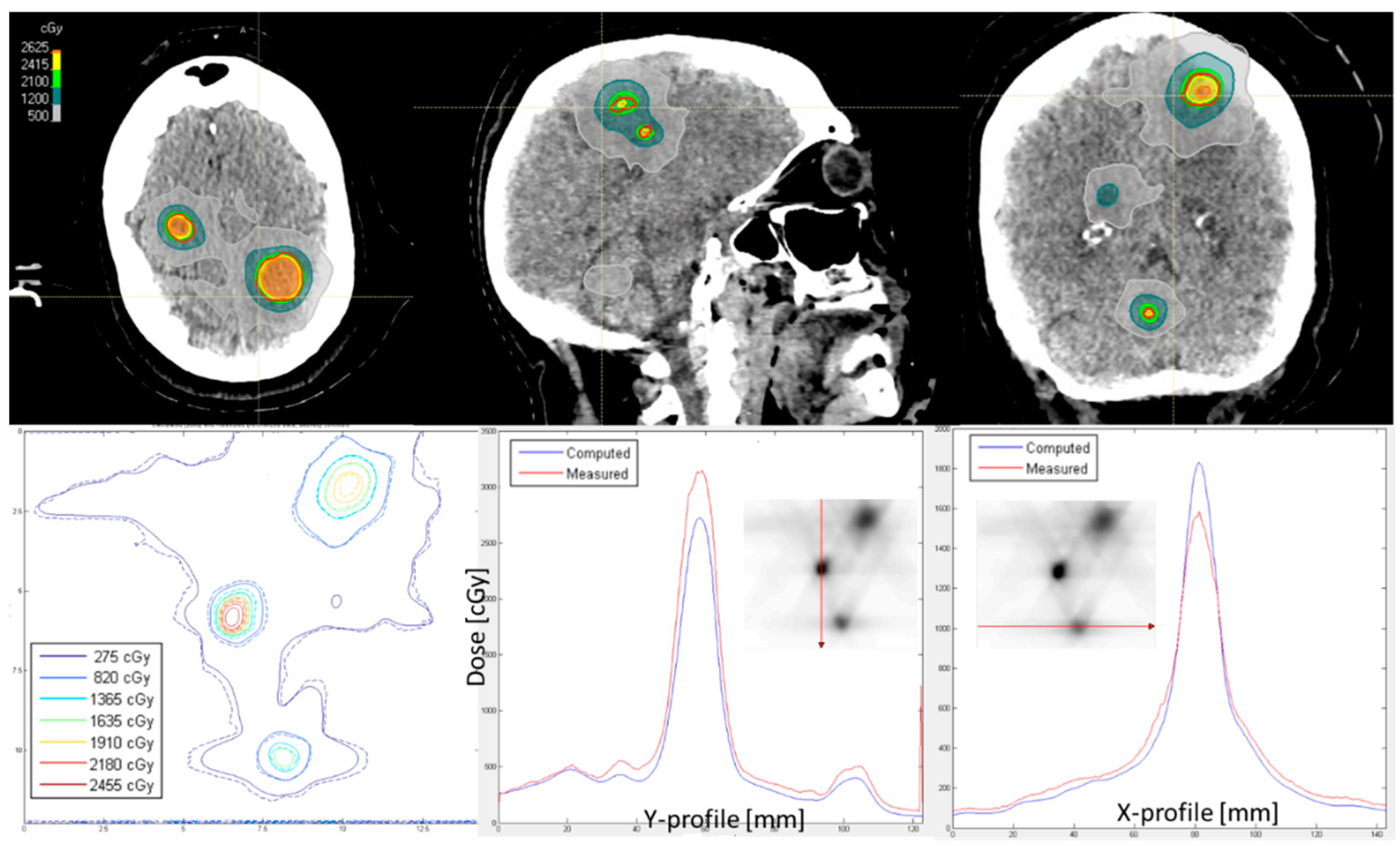

2.3. Film Dosimetry and Secondary Dose Calculation

- If the passing rate for the global dose difference of 3% and 1 mm distance-to-agreement was >95%, the plan could be approved by a medical physicist.

- If the passing rate for a global dose difference of 3% and 1 mm distance-to-agreement was 85–95%, and the dose differences were in the low dose range, then the plan could also be approved. If they were in the high dose range, then we checked whether the dose differences were small (within 5%) or large (5–10%) by calculating a relative percent difference to the global dose. We investigated whether it was possible to find out where this difference came from. It could be verified whether doses of the high dose of 15 Gy and the low dose of 0 Gy were measured. We performed the film dosimetry on a different matched LINAC to confirm the results. If necessary, and in consultation with a radiation oncologist, the plan was adjusted.

- If the passing rate for a global dose difference of 3% and 1 mm distance-to-agreement was <85%, we investigated whether it was possible to find out where this difference came from (for example, wrong unexposed film or dose calibration used, wrong orientation during scanning). If necessary, and in consultation with a radiation oncologist, the plan was adjusted.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

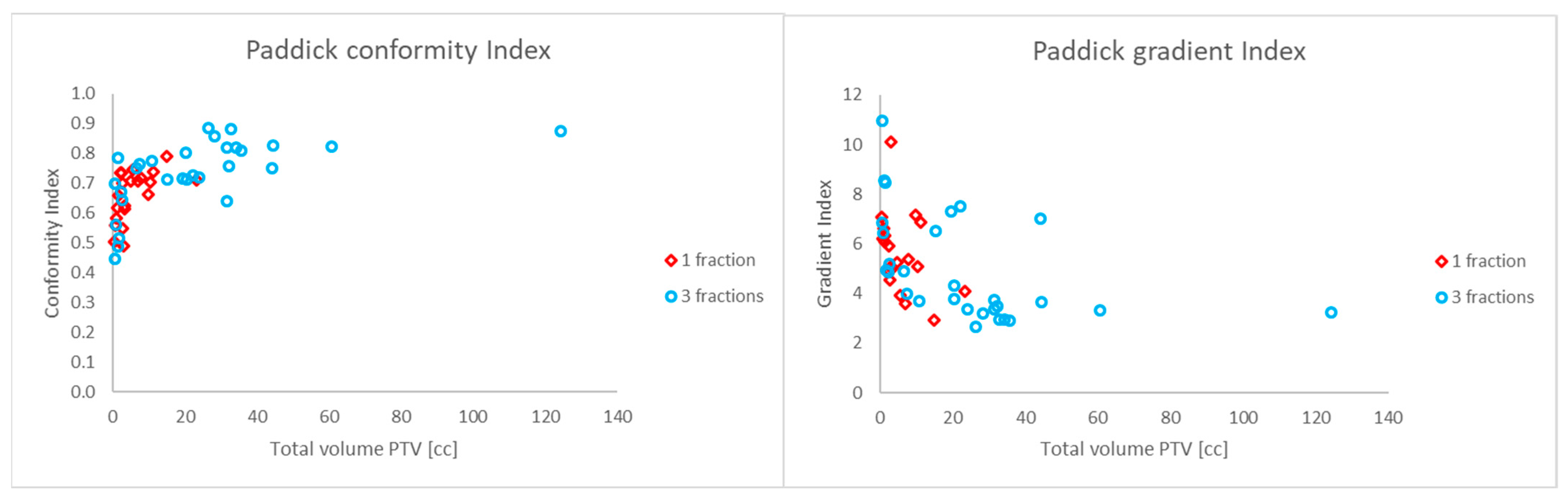

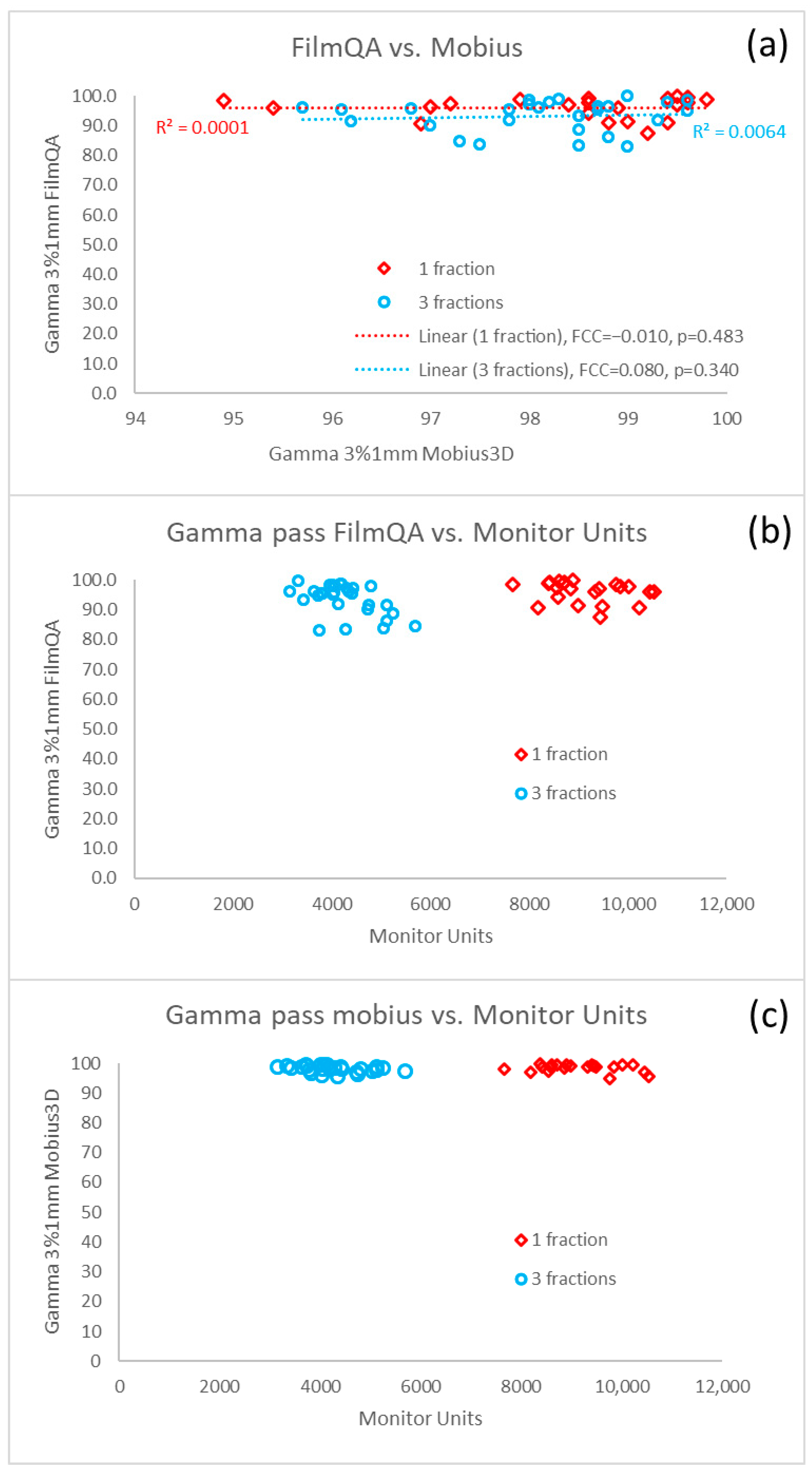

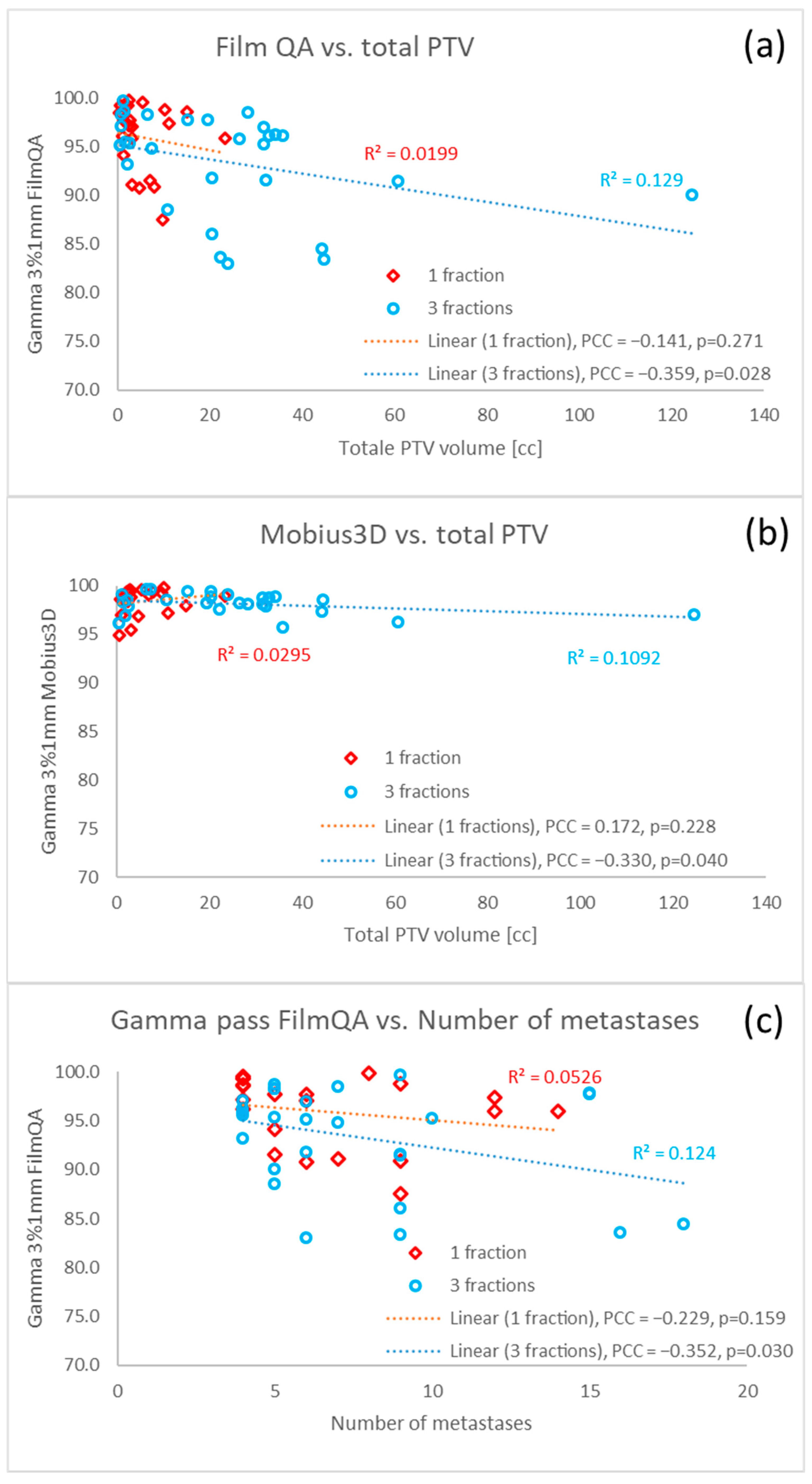

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BM(s) | Brain metastasis/metastases |

| DCAT | Dynamic conformal arc therapy |

| FFF | Flattening filter free |

| GTV | Gross tumor volume |

| LRA | Lateral response artefact |

| LINAC | Linear accelerator |

| MLC | Multileaf collimator |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| OAR | Organ at risk |

| PTV | Planning target volume |

| QA | Quality assurance |

| SIMT | Single-isocenter multi-target |

| SRT | Stereotactic radiotherapy |

| SIST | Single-isocenter single-target |

| VMAT | Volumetric modulated arc therapy |

| WBRT | Whole brain radiotherapy |

References

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Wright, C.H.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. Brain metastases: Epidemiology. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2018, 149, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoyama, H.; Shirato, H.; Tago, M.; Nakagawa, K.; Toyoda, T.; Hatano, K.; Kenjyo, M.; Oya, N.; Hirota, S.; Shioura, H.; et al. Stereotactic Radiosurgery Plus Whole-Brain Radiation Therapy vs. Stereotactic Radiosurgery Alone for Treatment of Brain Metastases. JAMA 2006, 295, 2483–2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, P.D.; Jaeckle, K.; Ballman, K.V.; Farace, E.; Cerhan, J.H.; Anderson, S.K.; Carrero, X.W.; Barker, F.G.; Deming, R.; Burri, S.H.; et al. Effect of Radiosurgery Alone vs. Radiosurgery With Whole Brain Radiation Therapy on Cognitive Function in Patients With 1 to 3 Brain Metastases: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2016, 316, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartgerink, D.; Bruynzeel, A.; Eekers, D.; Swinnen, A.; Hurkmans, C.; Wiggenraad, R.; Swaak-Kragten, A.; Dieleman, E.; van der Toorn, P.-P.; Oei, B.; et al. A Dutch phase III randomized multicenter trial: Whole brain radiotherapy versus stereotactic radiotherapy for 4–10 brain metastases. Neuro-Oncol. Adv. 2021, 3, vdab021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardcastle, N.; Tome, W.A. On a single isocenter volumetric modulated arc therapy SRS planning technique for multiple brain metastases. J. Radiosurg. SBRT 2012, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmaier, J.; Bodensohn, R.; Garny, S.; Hadi, I.; Fleischmann, D.F.; Eder, M.; Dinc, Y.; Reiner, M.; Corradini, S.; Parodi, K.; et al. Single isocenter stereotactic radiosurgery for patients with multiple brain metastases: Dosimetric comparison of VMAT and a dedicated DCAT planning tool. Radiat. Oncol. 2019, 14, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevaert, T.; Steenbeke, F.; Pellegri, L.; Engels, B.; Christian, N.; Hoornaert, M.-T.; Verellen, D.; Mitine, C.; De Ridder, M. Evaluation of a dedicated brain metastases treatment planning optimization for radiosurgery: A new treatment paradigm? Radiat. Oncol. 2016, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Gao, H.; Zhang, J.; Kirkpatrick, J.P.; Yin, F. Retrospective quality metrics review of stereotactic radiosurgery plans treating multiple targets using single-isocenter volumetric modulated arc therapy. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 2020, 21, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Thomas, E.M.; Li, J.; Yu, Y.; Andrews, D.; Markert, J.M.; Fiveash, J.B.; Shi, W.; Popple, R.A. Interinstitutional Plan Quality Assessment of 2 Linac-Based, Single-Isocenter, Multiple Metastasis Radiosurgery Techniques. Adv. Radiat. Oncol. 2020, 5, 1051–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, G.H.; Capone, L.; Tini, P.; Giraffa, M.; Gentile, P.; Minniti, G. Single-isocenter multiple-target stereotactic radiosurgery for multiple brain metastases: Dosimetric evaluation of two automated treatment planning systems. Radiat. Oncol. 2022, 17, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, G.M.; Popple, R.A.; Young, P.E.; Fiveash, J.B. Feasibility of Single-Isocenter Volumetric Modulated Arc Radiosurgery for Treatment of Multiple Brain Metastases. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2010, 76, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, G.M.; Popple, R.A.; Prendergast, B.M.; Spencer, S.A.; Thomas, E.M.; Stewart, J.G.; Guthrie, B.L.; Markert, J.M.; Fiveash, J.B. Plan quality and treatment planning technique for single isocenter cranial radiosurgery with volumetric modulated arc therapy. Pract. Radiat. Oncol. 2012, 2, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chin, K.; Robbins, J.R.; Kim, J.; Li, H.; Amro, H.; Chetty, I.J.; Gordon, J.; Ryu, S. Radiosurgery of multiple brain metastases with single-isocenter dynamic conformal arcs (SIDCA). Radiother. Oncol. 2014, 112, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, A.; Niebanck, M.; Juang, T.; Wang, Z.; Oldham, M. A comprehensive investigation of the accuracy and reproducibility of a multitarget single isocenter VMAT radiosurgery technique. Med. Phys. 2013, 40, 121725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, J.; Hood, R.; Yin, F.-F.; Salama, J.K.; Kirkpatrick, J.; Adamson, J. Is a single isocenter sufficient for volumetric modulated arc therapy radiosurgery when multiple intracranial metastases are spatially dispersed? Med. Dosim. 2016, 41, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggieri, R.; Naccarato, S.; Mazzola, R.; Ricchetti, F.; Corradini, S.; Fiorentino, A.; Alongi, F. Linac-based VMAT radiosurgery for multiple brain lesions: Comparison between a conventional multi-isocenter approach and a new dedicated mono-isocenter technique. Radiat. Oncol. 2018, 13, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petoukhova, A.; Snijder, R.; Wiggenraad, R.; de Boer-de Wit, L.; Mudde-van der Wouden, I.; Florijn, M.; Zindler, J. Quality of Automated Stereotactic Radiosurgery Plans in Patients with 4 to 10 Brain Metastases. Cancers 2021, 13, 3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roper, J.; Chanyavanich, V.; Betzel, G.; Switchenko, J.; Dhabaan, A. Single-Isocenter Multiple-Target Stereotactic Radiosurgery: Risk of Compromised Coverage. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2015, 93, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calmels, L.; Biancardo, S.B.N.; Sibolt, P.; Bekke, S.N.; Bjelkengren, U.; Wilken, E.; Geertsen, P.; Sjöström, D.; Behrens, C.F. Single-isocenter stereotactic non-coplanar arc treatment of 200 patients with brain metastases: Multileaf collimator size and setup uncertainties. Strahlenther. Onkol. 2022, 198, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J. A statistical model for analyzing the rotational error of single isocenter for multiple targets technique. Med. Phys. 2017, 44, 2115–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, H.; Tanabe, S.; Utsunomiya, S.; Yamada, T.; Sasamoto, R.; Nakano, T.; Saito, H.; Takizawa, T.; Sakai, H.; Ohta, A.; et al. Effect of setup error in the single-isocenter technique on stereotactic radiosurgery for multiple brain metastases. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 2020, 21, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eder, M.M.; Reiner, M.; Heinz, C.; Garny, S.; Freislederer, P.; Landry, G.; Niyazi, M.; Belka, C.; Riboldi, M. Single-isocenter stereotactic radiosurgery for multiple brain metastases: Impact of patient misalignments on target coverage in non-coplanar treatments. Z. Med. Phys. 2022, 32, 296–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanhope, C.; Chang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Yin, F.-F.; Kim, G.; Salama, J.K.; Kirkpatrick, J.; Adamson, J. Physics considerations for single-isocenter, volumetric modulated arc radiosurgery for treatment of multiple intracranial targets. Pract. Radiat. Oncol. 2016, 6, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, N.T.C.; Wong, W.L.; Lee, M.C.H.; Cheung, E.S.N.; Wu, P.Y. Geometric and dosimetric consequences of intra-fractional movement in single isocenter non-coplanar stereotactic radiosurgery. Radiat. Oncol. 2023, 18, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezzell, G.A. The spatial accuracy of two frameless, linear accelerator-based systems for single-isocenter, multitarget cranial radiosurgery. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 2017, 18, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Zhang, N.; Wang, E.M.; Wang, B.J.; Dai, J.Z.; Cai, P.W. Gamma knife radiosurgery as a primary treatment for prolactinomas. J. Neurosurg. 2000, 93 (Suppl. 3), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devic, S. Radiochromic film dosimetry: Past, present, and future. Phys. Med. 2011, 27, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D.; Micke, A.; Yu, X.; Chan, M.F. An efficient protocol for radiochromic film dosimetry combining calibration and measurement in a single scan. Med. Phys. 2012, 39, 6339–6350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micke, A.; Lewis, D.F.; Yu, X. Multichannel film dosimetry with nonuniformity correction. Med. Phys. 2011, 38, 2523–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niroomand-Rad, A.; Chiu-Tsao, S.; Grams, M.P.; Lewis, D.F.; Soares, C.G.; Van Battum, L.J.; Das, I.J.; Trichter, S.; Kissick, M.W.; Massillon-Jl, G.; et al. Report of AAPM Task Group 235 Radiochromic Film Dosimetry: An Update to TG-55. Med. Phys. 2020, 47, 5986–6025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouzen, J.A.; Petoukhova, A.L.; Wiggenraad, R.G.; Hutschemaekers, S.; Gadellaa-van Hooijdonk, C.G.; van der Voort van Zyp, N.C.M.G.; Mast, M.E.; Zindler, J.D. Development and evaluation of an automated EPTN-consensus based organ at risk atlas in the brain on MRI. Radiother. Oncol. 2022, 173, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Santvoort, J.; Wiggenraad, R.; Bos, P. Positioning Accuracy in Stereotactic Radiotherapy Using a Mask System With Added Vacuum Mouth Piece and Stereoscopic X-Ray Positioning. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2008, 72, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buitelaar-Gallé, M.; Van Egmond, J.; van Santvoort, J.; Roos, J.; Versluis, L.; De Vet, S.; Van Hameren, M.; Van Oorschot, T.; Wiggenraad, R.; Van Wingerden, J.; et al. EP-2339: Evaluation of a new mask system for stereotactic radiotherapy in brain lesions. Radiother. Oncol. 2018, 127, S1290–S1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zindler, J.D.; Bruynzeel, A.M.E.; Eekers, D.B.P.; Hurkmans, C.W.; Swinnen, A.; Lambin, P. Whole brain radiotherapy versus stereotactic radiosurgery for 4–10 brain metastases: A phase III randomised multicentre trial. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spenkelink, G.B.; Huijskens, S.C.; Zindler, J.D.; de Goede, M.; van der Star, W.J.; van Egmond, J.; Petoukhova, A.L. Comparative assessment and QA measurement array validation of Monte Carlo and Collapsed Cone dose algorithms for small fields and clinical treatment plans. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 2024, 25, e14522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paddick, I.; Lippitz, B. A simple dose gradient measurement tool to complement the conformity index. J. Neurosurg. 2006, 105, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuvret, L.; Noël, G.; Mazeron, J.-J.; Bey, P. Conformity index: A review. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2006, 64, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GAFCHROMIC™ Dosimetry Media, Type EBT-XD. Available online: https://www.ashland.com/industries/medical/radiotherapy-films/ebtxd (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Childress, N.L.; Dong, L.; Rosen, I.I. Rapid radiographic film calibration for IMRT verification using automated MLC fields. Med. Phys. 2002, 29, 2384–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childress, N.L.; Rosen, I.I. The design and testing of novel clinical parameters for dose comparison. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2003, 56, 1464–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyk, J.; Barnett, R.; Cygler, J.; Shragge, P. Commissioning and quality assurance of treatment planning computers. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 1993, 26, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miften, M.; Olch, A.; Mihailidis, D.; Moran, J.; Pawlicki, T.; Molineu, A.; Li, H.; Wijesooriya, K.; Shi, J.; Xia, P.; et al. Tolerance limits and methodologies for IMRT measurement-based verification QA: Recommendations of AAPMTask Group No. 218. Med. Phys. 2018, 45, e53–e83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermans, J.; Heukelom, S.; Hoffmans-Holtzer, N.; Marijnissen, H.; Nulens, A.; Pittomvils, G.; Raaijmakers, E.; Verellen, D.; Vieira, S. NCS Report 25: Process Management and Quality Assurance for Intracranial Stereotactic Treatment. Delft 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, D.; Schuler, J.; Takacs, I.; Peng, J.; Jenrette, J.; Vanek, K. Comparison of radiation dose spillage from the Gamma Knife Perfexion with that from volumetric modulated arc radiosurgery during treatment of multiple brain metastases in a single fraction. J. Neurosurg. 2014, 121 (Suppl. 2), 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D.; Chan, M.F. Correcting lateral response artifacts from flatbed scanners for radiochromic film dosimetry. Med. Phys. 2015, 42, 416–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marroquin, E.Y.L.; González, J.A.H.; López, M.A.C.; Barajas, J.E.V.; García-Garduño, O.A. Evaluation of the uncertainty in an EBT3 film dosimetry system utilizing net optical density. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 2016, 17, 466–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.B.; Kuo, L.; Li, T.; Li, X.; Ballangrud, A.M.; Lovelock, M.; Chan, M.F. Comparative study of SRS end-to-end QA processes of a diode array device and an anthropomorphic phantom loaded with GafChromic XD film. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 2022, 23, e13747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infusino, E.; Ianiro, A.; Luppino, S.; Nocentini, S.; Pugliatti, C.; Soriani, A. Evaluation of a planar diode matrix for SRS patient-specific QA in comparison with GAFchromic films. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 2023, 24, e13947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, L.; Tamborriello, A.; Subramanian, B.; Xu, X.; Ruruku, T.T. Assessing the sensitivity and suitability of a range of detectors for SIMT PSQA. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 2024, 25, e14343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alongi, F.; Fiorentino, A.; Gregucci, F.; Corradini, S.; Giaj-Levra, N.; Romano, L.; Rigo, M.; Ricchetti, F.; Beltramello, A.; Lunardi, G.; et al. First experience and clinical results using a new non-coplanar mono-isocenter technique (HyperArc™) for Linac-based VMAT radiosurgery in brain metastases. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 145, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.J.; Buckley, E.D.; Herndon, J.E.; Allen, K.J.; Dale, T.S.; Adamson, J.D.; Lay, L.; Giles, W.M.; Rodrigues, A.E.; Wang, Z.; et al. Outcomes in Patients With 4 to 10 Brain Metastases Treated With Dose-Adapted Single-Isocenter Multitarget Stereotactic Radiosurgery: A Prospective Study. Adv. Radiat. Oncol. 2021, 6, 100760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J.D.; Sebastian, N.T.; Chu, J.; DiCostanzo, D.; Bell, E.H.; Grecula, J.; Arnett, A.; Blakaj, D.M.; McGregor, J.; Elder, J.B.; et al. Single-Isocenter Multitarget Stereotactic Radiosurgery Is Safe and Effective in the Treatment of Multiple Brain Metastases. Adv. Radiat. Oncol. 2020, 5, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, J.; van Timmeren, J.E.; Mayinger, M.; Frei, S.; Borsky, K.; Stark, L.S.; Krayenbuehl, J.; Zamburlini, M.; Guckenberger, M.; Tanadini-Lang, S.; et al. Distance to isocenter is not associated with an increased risk for local failure in LINAC-based single-isocenter SRS or SRT for multiple brain metastases. Radiother. Oncol. 2021, 159, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minniti, G.; Capone, L.; Nardiello, B.; El Gawhary, R.; Raza, G.; Scaringi, C.; Bianciardi, F.; Gentile, P.; Paolini, S. Neurological outcome and memory performance in patients with 10 or more brain metastases treated with frameless linear accelerator (LINAC)-based stereotactic radiosurgery. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2020, 148, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, M.H.; Marcrom, S.R.; Patel, M.P.; Popple, R.A.; Travis, R.L.; McDonald, A.M.; Riley, K.O.; Markert, J.M.; Willey, C.D.; Bredel, M.; et al. Understanding the Effect of Prescription Isodose in Single-Fraction Stereotactic Radiosurgery on Plan Quality and Clinical Outcomes for Solid Brain Metastases. Neurosurgery 2023, 93, 1313–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crouzen, J.A.; Zindler, J.D.; Mast, M.E.; Kleijnen, J.J.E.; Versluis, M.C.; Hashimzadah, M.; Kiderlen, M.; van der Voort van Zyp, N.C.M.G.; Broekman, M.L.D.; Petoukhova, A.L. Local recurrence and radionecrosis after single-isocenter multiple targets stereotactic radiotherapy for brain metastases. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patients | Total | 50 |

|---|---|---|

| Irradiated metastases | Total | 356 |

| Irradiated metastases | Median | 6 |

| Irradiated metastases | Mean | 7 |

| Monitor Units | Mean ± SD total | 6321 ± 2510 |

| Mean ± SD 1 fraction | 9162 ± 765 | |

| Mean ± SD 3 fraction | 4263 ± 559 | |

| Total PTV volume | Median (cm3) (range) | 7.76 (0.56–124.5) |

| Irradiation time [s] | Mean (s) ± SD | 600 ± 90 |

| Brain-GTV | V5 (cm3) ± SD | 157 ± 270 |

| V12 (cm3) ± SD | 37 ± 69 | |

| Whole brain-GTVs > 12 Gy [%] | Mean (%) ± SD | 2.5 ± 0.05 |

| Paddick conformity index | Mean ± SD | 0.7 ± 0.1 |

| Paddick gradient index | Mean ± SD | 5.2 ± 1.9 |

| B (95% CI, p-Value) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Univariable | Multivariable | |

| Number of metastases | −0.001 (−0.01–0.008, 0.83) | - |

| Total volume of PTVs | 0.003 (0.002–0.004, <0.001) | 0.003 (0.001–0.004, <0.001) |

| Number of fractions | ||

| 1 | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| 3 | 0.071 (0.011–0.13, 0.02) | 0.47 (−0.036–0.076, 0.47) |

| B (95% CI, p-Value) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Univariable | Multivariable | |

| Number of metastases | 0.194 (0.05–0.337, 0.009) | 0.242 (0.12–0.364, <0.001) |

| Total volume of PTVs | −0.04 (−0.064–−0.017, 0.001) | −0.047 (−0.068–−0.027, <0.001) |

| Number of fractions | - | |

| 1 | 1.0 (reference) | |

| 3 | −0.636 (−1.737–0.466, 0.25) | |

| MU | Left (Gy) | Central (Gy) | Right (Gy) | LRA Left | LRA Right |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2500 | 29.82 | 29.33 | 29.82 | 1.67% | 1.67% |

| 1750 | 21.1 | 20.86 | 21.37 | 1.15% | 2.44% |

| 1250 | 15.26 | 14.93 | 15.11 | 2.21% | 1.21% |

| 450 | 5.68 | 5.58 | 5.65 | 1.79% | 1.25% |

| 100 | 1.39 | 1.39 | 1.41 | 0.00% | 1.44% |

| Uncertainties | Green Channel |

|---|---|

| Response curves and fitting procedure | 1.5% |

| Dose resolution of the system | 2.3% |

| Film reproducibility | 0.3% |

| Film uniformity | 0.3% |

| Lateral response artefact | 2.4% |

| Reproducibility of the response of the scanner | 0.3% |

| Total uncertainty | 3.6% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Petoukhova, A.L.; Bogers, S.L.C.; Crouzen, J.A.; de Goede, M.; van der Star, W.J.; Versluis, L.; Hashimzadah, M.; Zindler, J.D. Quality and Dosimetric Accuracy of Linac-Based Single-Isocenter Treatment Plans for Four to Eighteen Brain Metastases. Cancers 2025, 17, 3776. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233776

Petoukhova AL, Bogers SLC, Crouzen JA, de Goede M, van der Star WJ, Versluis L, Hashimzadah M, Zindler JD. Quality and Dosimetric Accuracy of Linac-Based Single-Isocenter Treatment Plans for Four to Eighteen Brain Metastases. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3776. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233776

Chicago/Turabian StylePetoukhova, Anna L., Stephanie L. C. Bogers, Jeroen A. Crouzen, Marc de Goede, Wilhelmus J. van der Star, Lia Versluis, Masomah Hashimzadah, and Jaap D. Zindler. 2025. "Quality and Dosimetric Accuracy of Linac-Based Single-Isocenter Treatment Plans for Four to Eighteen Brain Metastases" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3776. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233776

APA StylePetoukhova, A. L., Bogers, S. L. C., Crouzen, J. A., de Goede, M., van der Star, W. J., Versluis, L., Hashimzadah, M., & Zindler, J. D. (2025). Quality and Dosimetric Accuracy of Linac-Based Single-Isocenter Treatment Plans for Four to Eighteen Brain Metastases. Cancers, 17(23), 3776. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233776