Immunotherapy for Glioblastoma: A Focus on PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitors

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Immunotherapy for GBM

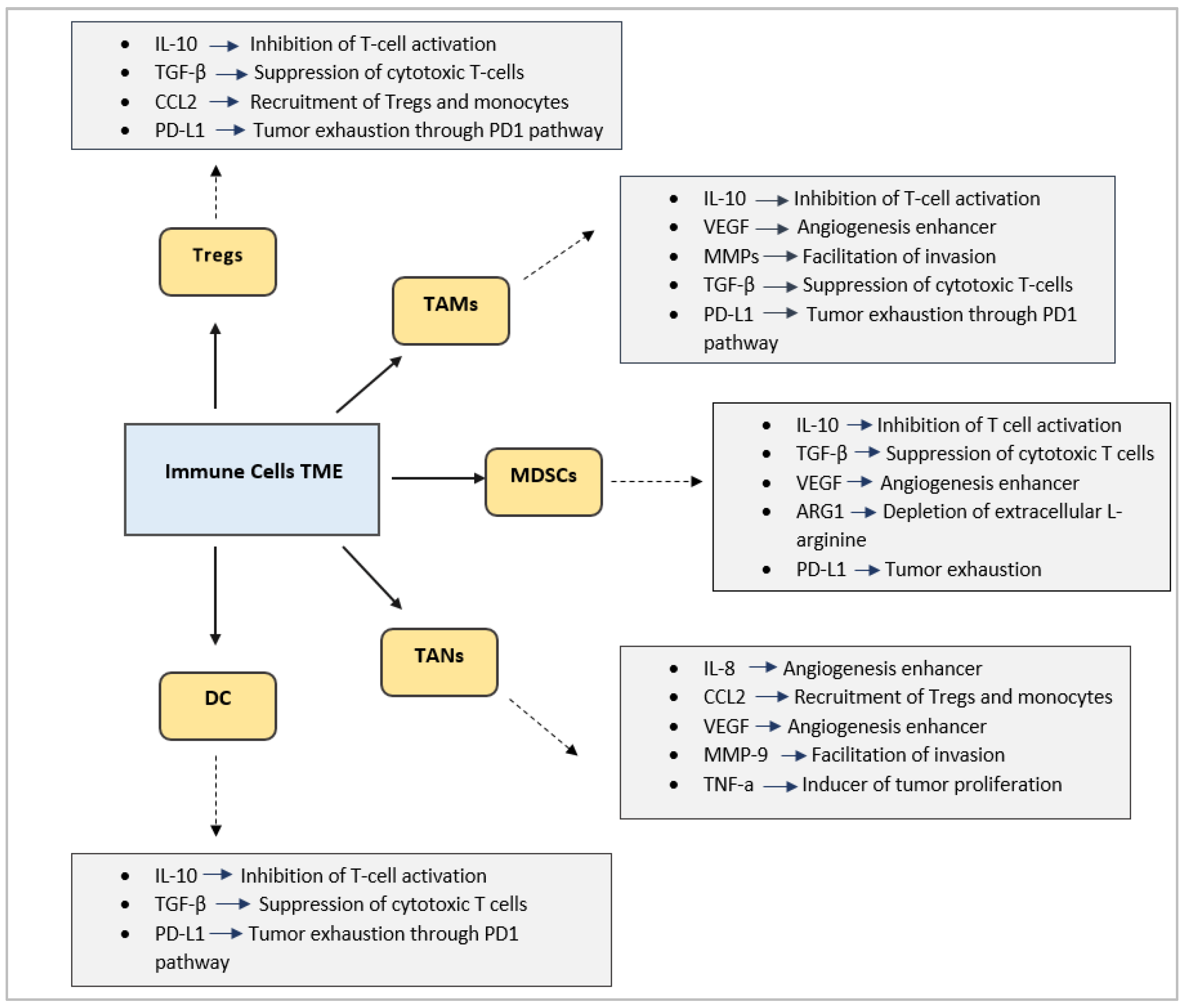

Immunosuppressive TME

3. The Role of Blood–Brain Barrier (BBB)

4. Combination of ICIs with Other GBM Treatments in the Preclinical Setting

5. Combination Treatments in the Clinical Setting

6. The Growing Role of Molecular Imaging and Radiogenomics

7. Limitations and Future Directions

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BBB | Blood–Brain Barrier |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| DC | Dendritic Cells |

| GBM | Glioblastoma |

| HIF-1a | Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1a |

| ICIs | Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors |

| IL-6R | Interleukin-6 Receptor |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| LAG-3 | Lymphocyte Activation Gene-3 |

| MDSCs | Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells |

| MGMT | Methylguanine-DNA Methyltransferase |

| MMPs | Matrix Metalloproteinases |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| NETs | Neutrophil Extracellular Traps |

| NK | Natural Killer |

| OS | Overall Survival |

| PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

| PFS | Progression-Free Survival |

| RT | Radiotherapy |

| SRT | Stereotactic Radiotherapy |

| TAMs | Tumor-Associated Macrophages |

| TANs | Tumor-Associated Neutrophils |

| TIM-3 | T cell Immunoglobulin and Mucin Domain 3 |

| TKI | Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor |

| TME | Tumor Microenvironment |

| TMZ | Temozolomide |

| TTFs | Tumor-Treating Fields |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

References

- Angom, R.S.; Nakka, N.M.R.; Bhattacharya, S. Advances in glioblastoma therapy: An update on current approaches. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, F.; Ali, H.; Lathia, G.D.; Chen, P. Immunotherapy for glioblastoma: Current state, challenges, and future perspectives. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2024, 21, 1354–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha Pinheiro, S.L.; Lemos, F.F.B.; Marques, H.S.; Silva Luz, M.; de Oliveira Silva, L.G.; Faria Souza Mendes Dos Santos, C.; da Costa Evangelista, K.; Calmon, M.S.; Sande Loureiro, M.; Freire de Melo, F. Immunotherapy in glioblastoma treatment: Current state and future prospects. World J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 14, 138–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharpe, M.A.; Baskin, D.S.; Johnson, R.D.; Baskin, A.M. Acquisition of immune privilege in GBM tumors: Role of prostaglandins and bile salts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Aaroe, A.; Liang, J.; Puduvalli, V.K. Tumor microenvironment in glioblastoma: Current and emerging concepts. Neurooncol. Adv. 2023, 5, vdad009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, M.; Ding, F.; Zheng, X.; Sun, S.; Du, J. Exploring tumor-associated macrophages in glioblastoma: From diversity to therapy. npj Precis. Oncol. 2025, 9, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Pang, L.; Dunterman, M.; Lesniak, M.S.; Heimberger, A.B.; Chen, P. Macrophages and microglia in glioblastoma: Heterogeneity, plasticity, and therapy. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 133, e163446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphries, W.; Wei, J.; Sampson, J.H.; Heimberger, A.B. The role of Tregs in glioma-mediated immunosuppression: Potential target for intervention. Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am. 2010, 21, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainwright, D.A.; Dey, M.; Chang, A.; Lesniak, M.S. Targeting Tregs in malignant brain cancer: Overcoming IDO. Front. Immunol. 2013, 4, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoozgar, Z.; Kloepper, J.; Ren, J.; Tay, R.E.; Kazer, S.W.; Kiner, E.; Krishnan, S.; Posada, J.M.; Ghosh, M.; Mamessier, E.; et al. Targeting Treg cells with GITR activation alleviates resistance to immunotherapy in murine glioblastomas. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, Y.; Guo, N.; Luan, J.; Cheng, J.; Hu, Z.; Jiang, P.; Jin, W.; Gao, X. The emerging role of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the glioma immune suppressive microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, C.; Cherry, C.; Bom, S.; Dykema, A.G.; Wang, R.; Thompson, E.; Zhang, M.; Li, R.; Ji, Z.; Hou, W.; et al. Distinct myeloid-derived suppressor cell populations in human glioblastoma. Science 2025, 387, eabm5214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essakhi, N.; Bertucci, A.; Baeza-Kallee, N.; Colin, C.; Lavignolle-Heguy, R.; Garcia-Gonzalez, P.; Argüello, R.J.; Tchoghandjian, A.; Tabouret, E. Metabolic adaptation of myeloid cells in the glioblastoma microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1431112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Li, X.; Wu, Y.; Hong, J.; Zhang, M. The prognostic significance of tumor-associated neutrophils and circulating neutrophils in glioblastoma (WHO CNS5 classification). BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lad, M.; Beniwal, A.S.; Jain, S.; Shukla, P.; Kalistratova, V.; Jung, J.; Shah, S.S.; Yagnik, G.; Saha, A.; Sati, A.; et al. Glioblastoma induces the recruitment and differentiation of dendritic-like “hybrid” neutrophils from skull bone marrow. Cancer Cell 2024, 42, 1549–1569.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardam, B.; Gargett, T.; Brown, M.P.; Ebert, L.M. Targeting the dendritic cell–T cell axis to develop effective immunotherapies for glioblastoma. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1261257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, L. Hypoxia within the glioblastoma tumor microenvironment: A master saboteur of novel treatments. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1384249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L. Modulation of the blood–brain barrier for drug delivery to brain. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvanitis, C.D.; Ferraro, G.B.; Jain, R.K. The blood–brain barrier and blood–tumour barrier in brain tumours and metastases. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2020, 20, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinot, O.L.; Wick, W.; Mason, W.; Henriksson, R.; Saran, F.; Nishikawa, R.; Carpentier, A.F.; Hoang-Xuan, K.; Kavan, P.; Cernea, D.; et al. Bevacizumab plus radiotherapy–temozolomide for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, H.; Zheng, G.; Bao, S.; Yang, H.; Shrestha, U.D.; Li, G.; Duan, X.; Du, X.; Ke, T.; Liao, C. Tumor perfusion enhancement by focused ultrasound-induced blood–brain barrier opening to potentiate anti-PD-1 immunotherapy of glioma. Transl. Oncol. 2024, 49, 102115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Englander, Z.K.; Wei, H.J.; Pouliopoulos, A.N.; Bendau, E.; Upadhyayula, P.; Jan, C.I.; Spinazzi, E.F.; Yoh, N.; Tazhibi, M.; McQuillan, N.M.; et al. Focused ultrasound mediated blood–brain barrier opening is safe and feasible in a murine pontine glioma model. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.Y.; Hsieh, H.Y.; Huang, C.Y.; Lin, C.Y.; Wei, K.C.; Liu, H.L. Focused ultrasound-induced blood-brain barrier opening to enhance interleukin-12 delivery for brain tumor immunotherapy: A preclinical feasibility study. J. Transl. Med. 2015, 13, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher, S.M.P.; Chisholm, A.; Lavelle, M.; Guthier, R.; Zhang, Y.; Power, C.; Berbeco, R. A study combining microbubble-mediated focused ultrasound and radiation therapy in the healthy rat brain and a F98 glioma model. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrieta, V.A.; Gould, A.; Kim, K.S.; Habashy, K.J.; Dmello, C.; Vázquez-Cervantes, G.I.; Palacín-Aliana, I.; McManus, G.; Amidei, C.; Gomez, C.; et al. Ultrasound-mediated delivery of doxorubicin to the brain results in immune modulation and improved responses to PD-1 blockade in gliomas. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zheng, X.; Gong, M.; Zhang, J. Delivery of a peptide–drug conjugate targeting the blood–brain barrier improved the efficacy of paclitaxel against glioma. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 79401–79407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; He, J.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, J.; Li, X.; Fu, T.; Xie, S.; Liu, X.; Tan, W. Transferrin Receptor-Targeted Aptamer-Drug Conjugate Overcomes Blood-Brain Barrier for Potent Glioblastoma Therapy. Bioconjugate Chem. 2025, 36, 1288–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, S.; Kim, E.H.; Chang, W.S.; Lee, W.S.; Kim, K.H.; Kim, J.K. Enhanced proton treatment with a LDLR-ligand peptide-conjugated gold nanoparticles targeting the tumor microenvironment in an infiltrative brain tumor model. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2022, 12, 198–209. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, L.; Zhao, X.; Fu, T.; Li, K.; He, Y.; Luo, Z.; Dai, L.; Zeng, R.; Cai, K. An iRGD-conjugated prodrug micelle with blood-brain-barrier penetrability for anti-glioma therapy. Biomaterials 2020, 230, 119666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Sun, M.; Li, Z.; Xiang, H.; Wang, Q.; Xin, X.; Shen, Y. Catalytic nanoreactors promote GLUT1-mediated BBB permeation by generating nitric oxide for potentiating glioblastoma ferroptosis. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 483, 149233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Xue, Y.; Yao, K.; Syeda, M.Z.; Xu, J.; Wu, J.; Wang, Z.; Tang, L.; Mu, Q. LAT1 targeted brain delivery of temozolomide and sorafenib for effective glioma therapy. Nano Res. 2023, 16, 9743–9751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chao, Y.; Zhao, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Pan, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, Q.; et al. Smart Nanomedicine to Enable Crossing Blood-Brain Barrier Delivery of Checkpoint Blockade Antibody for Immunotherapy of Glioma. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 664–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gampa, G.; Kenchappa, R.S.; Mohammad, A.S.; Parrish, K.E.; Kim, M.; Crish, J.F.; Luu, A.; West, R.; Hinojosa, A.Q.; Sarkaria, J.N.; et al. Enhancing brain retention of a KIF11 inhibitor significantly improves its efficacy in a mouse model of glioblastoma. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Gooijer, M.C.; de Vries, N.A.; Buckle, T.; Buil, L.C.M.; Beijnen, J.H.; Boogerd, W.; van Tellingen, O. Improved brain penetration and antitumor efficacy of temozolomide by inhibition of ABCB1 and ABCG2. Neoplasia 2018, 20, 710–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez-Macias, J.L.; Lee, Y.C.; Miller, E.; Finkelberg, T.; Zdioruk, M.; Berger, G.; Farquhar, C.E.; Nowicki, M.O.; Cho, C.F.; Fedeles, B.I.; et al. A Pt(IV)-conjugated brain penetrant macrocyclic peptide shows pre-clinical efficacy in glioblastoma. J. Control. Release 2022, 352, 623–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, C.G.; Shim, J.K.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, H.; Lee, J.E.; Kim, M.H.; Haam, K.; Jung, I.; Park, S.H.; et al. Effect of combined anti-PD-1 and temozolomide therapy in glioblastoma. Oncoimmunology 2018, 8, e1525243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, B.; Qi, N.; Li, J.; Zhang, G. Temozolomide combined with PD-1 Antibody therapy for mouse orthotopic glioma model. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 501, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karachi, A.; Yang, C.; Dastmalchi, F.; Sayour, E.J.; Huang, J.; Azari, H.; Long, Y.; Flores, C.; Mitchell, D.A.; Rahman, M. Modulation of temozolomide dose differentially affects T-cell response to immune checkpoint inhibition. Neuro Oncol. 2019, 21, 730–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytekin, E.; Maksoud, S.; Tannous, B.A.; Pehlivan, S.B.; Badr, C.E. Dual-action nanotherapy: Temozolomide-loaded, anti-PD-L1 scFv-functionalized lipid nanocarriers for targeted glioblastoma therapy. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. Off. J. Eur. Fed. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 213, 107255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; See, A.P.; Phallen, J.; Jackson, C.M.; Belcaid, Z.; Ruzevick, J.; Durham, N.; Meyer, C.; Harris, T.J.; Albesiano, E.; et al. Anti-PD-1 blockade and stereotactic radiation produce long-term survival in mice with intracranial gliomas. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2013, 86, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.E.; Patel, M.A.; Mangraviti, A.; Kim, E.S.; Theodros, D.; Velarde, E.; Liu, A.; Sankey, E.W.; Tam, A.; Xu, H.; et al. Combination Therapy with Anti-PD-1, Anti-TIM-3, and Focal Radiation Results in Regression of Murine Gliomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocito, C.; Branchtein, M.; Zhou, X.K.; Gongora, T.; Dahmane, N.; Greenfield, J.P. Single-dose radiotherapy is more effective than fractionation when combined with anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in glioblastoma. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Feng, M.; Li, Y.; Su, Z.; Li, W.; Xiong, Y.; Gao, H.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Combined anti-PD-L1 and anti-VEGFR2 therapy promotes the antitumor immune response in GBM by reprogramming tumor microenvironment. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, D.A.; Brandes, A.A.; Omuro, A.; Mulholland, P.; Lim, M.; Wick, A.; Baehring, J.; Ahluwalia, M.S.; Roth, P.; Bähr, O.; et al. Effect of Nivolumab vs Bevacizumab in Patients With Recurrent Glioblastoma: The CheckMate 143 Phase 3 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020, 6, 1003–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omuro, A.; Vlahovic, G.; Lim, M.; Sahebjam, S.; Baehring, J.; Cloughesy, T.; Voloschin, A.; Ramkissoon, S.H.; Ligon, K.L.; Latek, R.; et al. Nivolumab with or without ipilimumab in patients with recurrent glioblastoma: Results from exploratory phase I cohorts of CheckMate 143. Neuro-Oncol. 2018, 20, 674–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omuro, A.; Brandes, A.A.; Carpentier, A.F.; Idbaih, A.; Reardon, D.A.; Cloughesy, T.; Sumrall, A.; Baehring, J.; van den Bent, M.; Bähr, O.; et al. Radiotherapy combined with nivolumab or temozolomide for newly diagnosed glioblastoma with unmethylated MGMT promoter: An international randomized phase III trial. Neuro Oncol. 2023, 25, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sloan, A.E.; Winter, K.; Gilbert, M.R.; Aldape, K.; Choi, S.; Wen, P.Y.; Butowski, N.; Iwamoto, F.M.; Raval, R.R.; Voloschin, A.D.; et al. NRG-BN002: Phase I study of ipilimumab, nivolumab, and the combination in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2024, 26, 1628–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouessel, D.; Ken, S.; Gouaze-Andersson, V.; Piram, L.; Mervoyer, A.; Larrieu-Ciron, D.; Cabarrou, B.; Lusque, A.; Robert, M.; Frenel, J.S.; et al. Hypofractionated Stereotactic Re-irradiation and Anti-PDL1 Durvalumab Combination in Recurrent Glioblastoma: STERIMGLI Phase I Results. Oncologist 2023, 28, e817–e825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishijima, T.F.; Shachar, S.S.; Nyrop, K.A.; Muss, H.B. Safety and Tolerability of PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitors Compared with Chemotherapy in Patients with Advanced Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Oncologist 2017, 22, 470–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.; Weller, M.; Idbaih, A.; Steinbach, J.; Finocchiaro, G.; Raval, R.R.; Ansstas, G.; Baehring, J.; Taylor, J.W.; Honnorat, J.; et al. Phase III trial of chemoradiotherapy with temozolomide plus nivolumab or placebo for newly diagnosed glioblastoma with methylated MGMT promoter. Neuro Oncol. 2022, 24, 1935–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weathers, S.P.; Li, X.; Zhu, H.; Damania, A.V.; Knafl, M.; McKinley, B.; Lin, H.; Harrison, R.A.; Majd, N.K.; O’Brien, B.J.; et al. Improved overall survival in an anti-PD-L1 treated cohort of newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients is associated with distinct immune, mutation, and gut microbiome features: A single arm prospective phase I/II trial. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weathers, S.P.; Kamiya-Matsuoka, C.; Majd, N.; Ashu, A.; Thompson, C.; Gachimova, E.; Aaroe, A.; Patel, C.; Loghin, M.; O’Brien, B.; et al. Safety run-in results of a phase I/II study to evaluate atezolizumab in combination with cabozantinib in patients with recurrent glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2023, 25, v67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. A Phase I Trial of Anti-TIGIT Antibody AB154 in Combination with Anti-PD-1 Antibody AB122 for Recurrent Glioblastoma. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04729959 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins. A Phase I Trial of Anti-Tim-3 in Combination with Anti-PD-1 and SRS in Recurrent GBM. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03961971 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Omuro, A. A Multi-Center Phase 0/I Trial of Anti-TIGIT Antibody AB154 in Combination with Anti-PD-1 Antibody AB122 for Recurrent Glioblastoma. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04656535 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins. A Phase I Trial of Anti-LAG-3 or Anti-CD137 Alone and in Combination with Anti-PD-1 in Patients with Recurrent GBM. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02658981 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Sharma, G.; Braga, M.C.; Da Pieve, C.; Szopa, W.; Starzetz, T.; Plate, K.H.; Kaspera, W.; Kramer-Marek, G. Immuno-PET Imaging of Tumour PD-L1 Expression in Glioblastoma. Cancers 2023, 15, 3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallegos, C.A.; Lu, Y.; Clements, J.C.; Song, P.N.; Lynch, S.E.; Mascioni, A.; Jia, F.; Hartman, Y.E.; Massicano, A.V.F.; Houson, H.A.; et al. [89Zr]-CD8 ImmunoPET imaging of glioblastoma multiforme response to combination oncolytic viral and checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy reveals CD8 infiltration differential changes in preclinical models. Theranostics 2024, 14, 911–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincze, S.R.; Jaswal, A.P.; Frederico, S.C.; Nisnboym, M.; Li, B.; Xiong, Z.; Sever, R.E.; Sneiderman, C.T.; Rodgers, M.; Day, K.E.; et al. ImmunoPET imaging of TIGIT in the glioma microenvironment. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hautiere, M.; Vivier, D.; Dorval, P.; Pineau, D.; Kereselidze, D.; Denis, C.; Herbet, A.; Costa, N.; Bernhard, C.; Goncalves, V.; et al. Preoperative PET imaging and fluorescence-guided surgery of human glioblastoma using dual-labeled antibody targeting ETA receptors in a preclinical mouse model: A theranostic approach. Theranostics 2024, 14, 6268–6280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kang, X.; Ma, J.; Li, J.; Chen, W.; Yang, S.; Li, W.; Shi, Y.; Qi, J. Hierarchical targeting nanoplatform for NIR-II photoacoustic imaging and photo-activated synergistic immunotherapy of glioblastoma. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2419395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F.; Fan, Z.; Li, S.; Li, L.; Sun, T.; Qiu, Y.; Nie, L.; Huang, G. Tumor Microenvironment Activated Photoacoustic-Fluorescence Bimodal Nanoprobe for Precise Chemo-immunotherapy and Immune Response Tracing of Glioblastoma. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 19753–19766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahanger, A.B.; Aalam, S.W.; Masoodi, T.A.; Shah, A.; Khan, M.A.; Bhat, A.A.; Assad, A.; Macha, M.A.; Bhat, M.R. Radiogenomics and machine learning predict oncogenic signaling pathways in glioblastoma. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazerooni, A.; Akbari, H.; Hu, X.; Bommineni, V.; Grigoriadis, D.; Toorens, E.; Sako, C.; Mamourian, E.; Ballinger, D.; Sussman, R.; et al. The radiogenomic and spatiogenomic landscapes of glioblastoma and their relationship to oncogenic drivers. Commun. Med. 2025, 5, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegi, M.E.; Diserens, A.C.; Gorlia, T.; Hamou, M.F.; De Tribolet, N.; Weller, M.; Kros, J.M.; Hainfellner, J.A.; Mason, W.; Mariani, L.; et al. MGMT Gene Silencing and Benefit from Temozolomide in Glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 997–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Chen, A.X.; Gartrell, R.D.; Silverman, A.M.; Aparicio, L.; Chu, T.; Bordbar, D.; Shan, D.; Samanamud, J.; Mahajan, A.; et al. Immune and genomic correlates of response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in glioblastoma. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 462–469, Erratum in: Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Lim, J.; Kang, H.; Jeong, J.-Y.; Joung, J.-G.; Heo, J.; Jung, D.; Cho, K.; Jung, H. An Predictive biomarkers for the responsiveness of recurrent glioblastomas to activated killer cell immunotherapy. Cell Biosci. 2023, 13, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, M.; Xu, Z.; Wang, L.; Chen, H.; Wan, X.; Xu, H.; Yang, S.; Tu, Q. An analysis of prognostic risk and immunotherapy response of glioblastoma patients based on single-cell landscape and nitrogen metabolism. Neurobiol. Dis. 2025, 211, 106935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellingson, B.M.; Lai, A.; Harris, R.J.; Selfridge, J.M.; Yong, W.H.; Das, K.; Pope, W.B.; Nghiemphu, P.L.; Vinters, H.V.; Liau, L.M.; et al. Probabilistic radiographic atlas of glioblastoma phenotypes. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2013, 34, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakas, S.; Akbari, H.; Pisapia, J.; Martinez-Lage, M.; Rozycki, M.; Rathore, S.; Dahmane, N.; O’Rourke, D.M.; Davatzikos, C. In Vivo Detection of EGFRvIII in Glioblastoma via Perfusion Magnetic Resonance Imaging Signature Consistent with Deep Peritumoral Infiltration: The φ-Index. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 4724–4734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrillon, A.; Biard, L.; Lee, S.M. Incorporating patient-reported outcomes in dose-finding clinical trials with continuous patient enrollment. J. Biopharm. Stat. 2025, 35, 839–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farber, S.H.; Elsamadicy, A.A.; Atik, A.F.; Suryadevara, C.M.; Chongsathidkiet, P.; Fecci, P.E.; Sampson, J.H. The Safety of available immunotherapy for the treatment of glioblastoma. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2017, 16, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Le, S.B.; Ghiaseddin, A.; Manektalia, H.; Li, M.; O’Dell, A.; Rahman, M.; Tran, D.D. 591 In-situ vaccination by tumor treating fields and anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in patients with large residual GBM results in robust T cell selection and expansion, high response rate, and extended survival. J. Immunother. Cancer 2024, 12, 2. [Google Scholar]

| Method | Major Advantages | Preclinical Studies | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Focused Ultrasound (FUS) + Circulating Microbubbles | -Consistent, reproducible, transient BBB opening -Noninvasive -No serious damage to the brain tissue -Can enhance delivery of ICIs -Precise targeting via MRI guidance | -Increase in CD4+ and CD8+ T cell infiltration in C6 glioma rats when combined with anti-PD-1. | [21] |

| -Increased etoposide delivery in an orthotopic pontine glioma model. | [22] | ||

| -Increase in the tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte population after combination of FUS-induced BBB opening and IL-12 in C6 glioma rats. | [23] | ||

| -Enhanced radiotherapy effects, including increase in apoptosis of tumor cells in an F98 rat glioma model. | [24] | ||

| -Increased survival and immune memory in orthotopic GL261 and CT-2A model after combination of FUS/MB with doxorubicin and anti-PD-1 therapy. | [25] | ||

| Receptor-Mediated Transcytosis (RMT) | -Tumor selectivity -Delivery of various drug types, like peptides, antibodies, and drug-loaded nanoparticles -Fewer systemic side effects | -Increased BBB penetration and tumor uptake in orthotopic glioma models when Angiopep-2 (LRP1)–paclitaxel conjugate was evaluated. | [26] |

| -Increased antitumor activity in both subcutaneous and orthotopic GBM models of a TfR-targeted aptamer–drug conjugate (ApDC). | [27] | ||

| -Reduction in tumor volume and preferential invasion in the tumor microenvironment of an F98 glioma rat model when LDLR ligand-functionalized gold nanoparticles were used. | [28] | ||

| -Increased BBB penetration and tumor uptake in an orthotopic glioma model when an αvβ integrin and NRP-1-mediated transport was achieved using iRGD modified polymeric micelles. | [29] | ||

| Transporter-Mediated Transcytosis (TMT) | -Tumor selectivity -Delivery of various drug types, like peptides, antibodies, and drug-loaded nanoparticles -Fewer systemic side effects | -Ιnduction of tumor cell apoptosis and reduced tumor burden in an orthotopic GBM model when GLUT1-mediated BBB permeabilization of magnetite NPs with arginine modification was achieved. | [30] |

| -Increased tumor accumulation of LAT1-targeting nanoparticles co-loaded with TMZ and sorafenib in an orthotopic GBM model. | [31] | ||

| -Improved BBB-crossing capability in an orthotopic glioma tumor model of a smart polymer that crosses the BBB via choline transporters. | [32] | ||

| Efflux Transporter Inhibitors | -Broad applicability -Sensitization of tumor-initiating cells/GBM stem-like cells | -Increased tumor uptake of ispinesib (P-gp/Bcrp substrate) after co-administration with the dual P-gp/BCRP inhibitor elacridar in orthotopic GBM models. | [33] |

| -Increased brain TMZ levels and higher antitumor effects after genetic knockout of Abcb1a/b and Abcg2 in intracranial mouse models. | [34] | ||

| Cell-penetrating peptide (CPP)–Drug Conjugates | -Enhanced solubility and bioavailability -Versatile delivery -Targeting and specificity | -Increased platinum levels in a murine GBM xenograft model and increased survival after administration of a Pt complex conjugated to a brain-penetrant macrocyclic peptide. | [35] |

| Combination | Key Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| anti-PD-1 + TMZ |

| [36] |

| [37] | |

| [38] | |

| nanocarriers (anti-PD-L1 + TMZ) |

| [39] |

| anti-PD-1 + RT |

| [40] |

| [41] | |

| anti-PD-1 + RT + anti-TIM-3 |

| [42] |

| anti-PD-L1 + anti-VEGFR2 |

| [43] |

| Phase/ID | Population | Tested Combinations | Status | Key Results | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| III NCT02667587 | Newly diagnosed GBM (MGMT methylated promoter) patients | Nivolumab + RT ± TMZ | Completed |

| [50] |

| I/II NCT02866747 | Recurrent and newly diagnosed GBM patients | Durvalumab + hypofractionated RT | Completed |

| [49] |

| I/II NCT03174197 | Newly diagnosed GBM patients | Atezolizumab (PD-L1 + temozolomide + radiation) | Active—not recruiting |

| [51] |

| I/II NCT05039281 | Recurrent GBM patients | Atezolizumab + cabozantinib (TKI) | Recruiting/early phase |

| [52] |

| II (early) NCT04729959 | Recurrent GBM patients | Atezolizumab + tocilizumab (IL-6R inhibitor) + SRT | Active—not recruiting |

| [53] |

| I NCT03961971 | Recurrent GBM patients | Spartalizumab + MBG453 (anti-TIM-3) + SRT | Active—not recruiting |

| [54] |

| I NCT04656535 | Recurrent GBM patients | Zimberelimab + domvanalimab (anti-TIGIT) | Active—not recruiting |

| [55] |

| I NCT02658981 | Recurrent GBM patients | Nivolumab + BMS-986016 (anti-LAG-3) | Completed |

| [56] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zoi, V.; Galani, V.; Sioka, C.; Alexiou, G.A.; Kyritsis, A.P. Immunotherapy for Glioblastoma: A Focus on PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitors. Cancers 2025, 17, 3777. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233777

Zoi V, Galani V, Sioka C, Alexiou GA, Kyritsis AP. Immunotherapy for Glioblastoma: A Focus on PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitors. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3777. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233777

Chicago/Turabian StyleZoi, Vasiliki, Vasiliki Galani, Chrissa Sioka, Georgios A. Alexiou, and Athanassios P. Kyritsis. 2025. "Immunotherapy for Glioblastoma: A Focus on PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitors" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3777. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233777

APA StyleZoi, V., Galani, V., Sioka, C., Alexiou, G. A., & Kyritsis, A. P. (2025). Immunotherapy for Glioblastoma: A Focus on PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitors. Cancers, 17(23), 3777. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233777