Information Behaviour and Knowledge of Patients Before Radical Prostatectomy

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Cohort

3.2. Informational and Decisional Behaviour

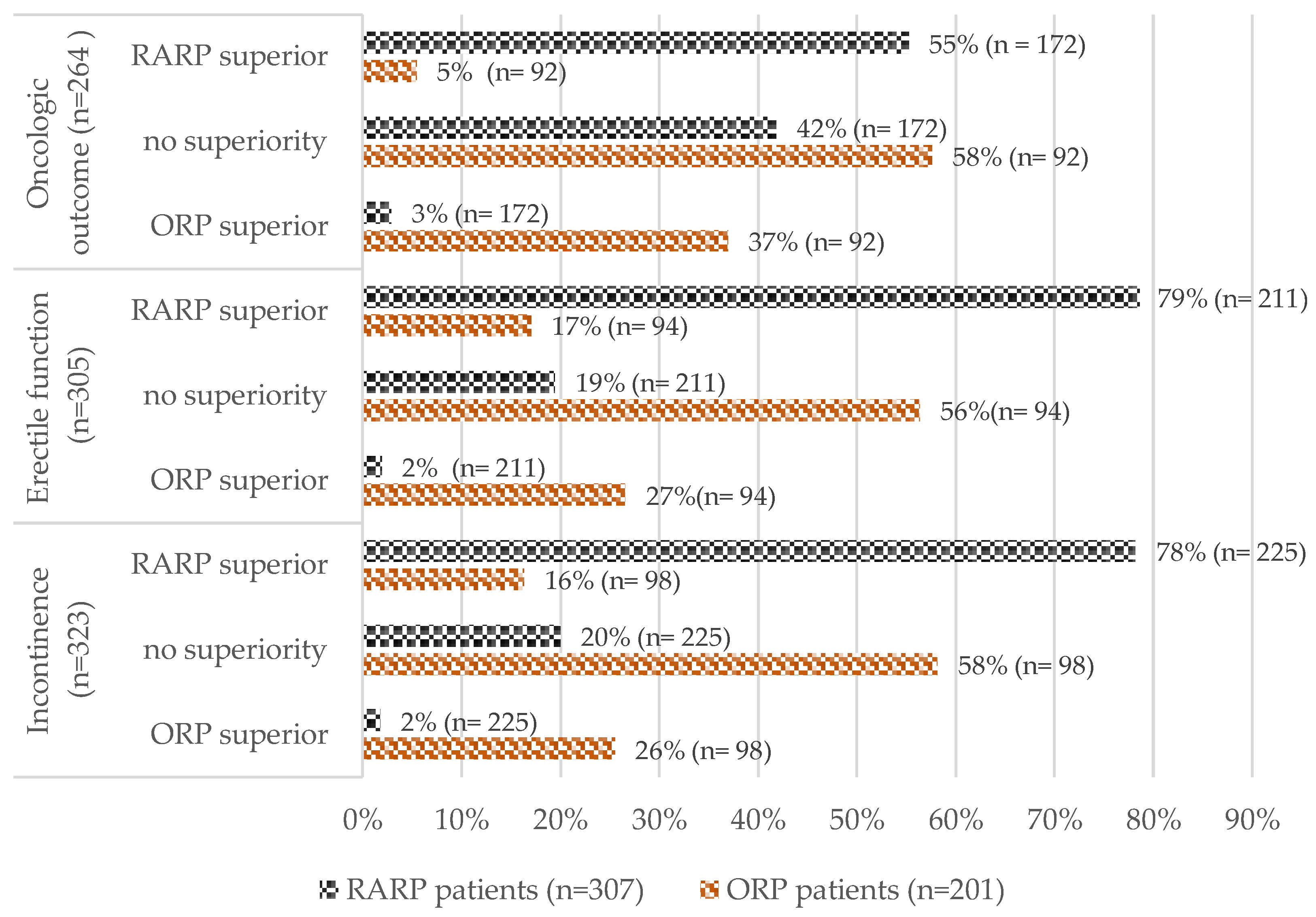

3.3. Perception of Outcomes

Factors for Misperception of Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pyrgidis, N.; Volz, Y.; Ebner, B.; Westhofen, T.; Staehler, M.; Chaloupka, M.; Apfelbeck, M.; Jokisch, F.; Bischoff, R.; Marcon, J.; et al. Evolution of Robotic Urology in Clinical Practice from the Beginning to Now: Results from the GRAND Study Register. Eur. Urol. Focus 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maynou, L.; Mehtsun, W.T.; Serra-Sastre, V.; Papanicolas, I. Patterns of Adoption of Robotic Radical Prostatectomy in the United States and England. Health Serv. Res. 2021, 56, 1441–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basiri, A.; de la Rosette, J.J.; Tabatabaei, S.; Woo, H.H.; Laguna, M.P.; Shemshaki, H. Comparison of Retropubic, Laparoscopic and Robotic Radical Prostatectomy: Who Is the Winner? World J. Urol. 2018, 36, 609–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novara, G.; Ficarra, V.; Rosen, R.C.; Artibani, W.; Costello, A.; Eastham, J.A.; Graefen, M.; Guazzoni, G.; Shariat, S.F.; Stolzenburg, J.-U.; et al. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Perioperative Outcomes and Complications After Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy. Eur. Urol. 2012, 62, 431–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrosini, F.; Knipper, S.; Tilki, D.; Heinzer, H.; Salomon, G.; Michl, U.; Steuber, T.; Pose, R.M.; Budäus, L.; Maurer, T.; et al. Robot-Assisted vs Open Retropubic Radical Prostatectomy: A Propensity Score-Matched Comparative Analysis Based on 15 Years and 18,805 Patients. World J. Urol. 2024, 42, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okhawere, K.E.; Shih, I.-F.; Lee, S.-H.; Li, Y.; Wong, J.A.; Badani, K.K. Comparison of 1-Year Health Care Costs and Use Associated With Open vs Robotic-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e212265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chen, C.; Liu, Y.; Wen, Z.; Li, H.; Huang, H.; Yang, X. Comparative Analysis of Perioperative Outcomes in Obese Patients Undergoing Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy (RARP) versus Open Radical Prostatectomy (ORP): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Robot. Surg. 2024, 18, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Yang, Z.; Qi, L.; Chen, M. Robot-Assisted and Laparoscopic vs Open Radical Prostatectomy in Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer: Perioperative, Functional, and Oncological Outcomes. Medicine 2019, 98, e15770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyberg, M.; Hugosson, J.; Wiklund, P.; Sjoberg, D.; Wilderäng, U.; Carlsson, S.V.; Carlsson, S.; Stranne, J.; Steineck, G.; Haglind, E.; et al. Functional and Oncologic Outcomes Between Open and Robotic Radical Prostatectomy at 24-Month Follow-up in the Swedish LAPPRO Trial. Eur. Urol. Oncol 2018, 1, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baunacke, M.; Schmidt, M.-L.; Thomas, C.; Groeben, C.; Borkowetz, A.; Koch, R.; Chun, F.K.H.; Weissbach, L.; Huber, J. Long-Term Functional Outcomes after Robotic vs. Retropubic Radical Prostatectomy in Routine Care: A 6-Year Follow-up of a Large German Health Services Research Study. World J. Urol. 2020, 38, 1701–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, J.; Jeong, I.G.; Jeon, H.G.; Jeong, C.W.; Lee, S.; Jeon, S.S.; Byun, S.S.; Kwak, C.; Ahn, H. Long-Term Oncologic Outcomes of Robot-Assisted versus Open Radical Prostatectomy for Prostate Cancer with Seminal Vesicle Invasion: A Multi-Institutional Study with a Minimum 5-Year Follow-Up. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 149, 1951–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilic, D.; Evans, S.M.; Allan, C.A.; Jung, J.H.; Murphy, D.; Frydenberg, M. Laparoscopic and Robotic-Assisted versus Open Radical Prostatectomy for the Treatment of Localised Prostate Cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2017, CD009625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, P.C.; Mostwin, J.L. Radical Prostatectomy and Cystoprostatectomy with Preservation of Potency. Results Using a New Nerve-sparing Technique. Br. J. Urol. 1984, 56, 694–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herlemann, A.; Cowan, J.E.; Carroll, P.R.; Cooperberg, M.R. Community-Based Outcomes of Open versus Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy. Eur. Urol. 2018, 73, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groeben, C.; Koch, R.; Baunacke, M.; Wirth, M.P.; Huber, J. Robots Drive the German Radical Prostatectomy Market: A Total Population Analysis from 2006 to 2013. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2016, 19, 412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, A.; Lewis, D.; Charman, S.C.; Mason, M.; Clarke, N.; Sullivan, R.; van der Meulen, J. Determinants of Patient Mobility for Prostate Cancer Surgery: A Population-Based Study of Choice and Competition. Eur. Urol. 2018, 73, 822–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, A.; Lewis, D.; Mason, M.; Purushotham, A.; Sullivan, R.; van der Meulen, J. Effect of Patient Choice and Hospital Competition on Service Configuration and Technology Adoption within Cancer Surgery: A National, Population-Based Study. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 1445–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhateeb, S.; Lawrentschuk, N. Consumerism and Its Impact on Robotic-assisted Radical Prostatectomy. BJU Int. 2011, 108, 1874–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat Personen. Die Das Internet 2023 Zur Beschaffung von Gesundheitsrelevanten Informationen Genutzt Haben. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tin00101/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 13 February 2024).

- Siegel, F.P.; Kuru, T.H.; Boehm, K.; Leitsmann, M.; Probst, K.A.; Struck, J.P.; Huber, J.; Borgmann, H.; Salem, J. Radical Prostatectomy on YouTube: Education or Disinformation? Arch. Esp. Urol. 2023, 76, 764–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degner, L.F.; Sloan, J.A. Decision Making during Serious Illness: What Role Do Patients Really Want to Play? J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1992, 45, 941–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, J.; Jay, C.; Harper, S.; Davies, A.; Vega, J.; Todd, C. Web Use for Symptom Appraisal of Physical Health Conditions: A Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahsavar, Y.; Choudhury, A. User Intentions to Use ChatGPT for Self-Diagnosis and Health-Related Purposes: Cross-Sectional Survey Study. JMIR Hum. Factors 2023, 10, e47564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, J.; Maatz, P.; Muck, T.; Keck, B.; Friederich, H.-C.; Herzog, W.; Ihrig, A. The Effect of an Online Support Group on Patients׳ Treatment Decisions for Localized Prostate Cancer: An Online Survey. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2017, 35, 37.e19–37.e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lind, M.; Visentini, M.; Mäntylä, T.; Del Missier, F. Choice-Supportive Misremembering: A New Taxonomy and Review. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbett, R.E.; Wilson, T.D. The Halo Effect: Evidence for Unconscious Alteration of Judgments. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 35, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerger, B.D.; Bernal, A.; Paustenbach, D.J.; Huntley-Fenner, G. Halo and Spillover Effect Illustrations for Selected Beneficial Medical Devices and Drugs. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirkin, J.N.; Lowrance, W.T.; Feifer, A.H.; Mulhall, J.P.; Eastham, J.E.; Elkin, E.B. Direct-To-Consumer Internet Promotion Of Robotic Prostatectomy Exhibits Varying Quality Of Information. Health Aff. 2012, 31, 760–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stehr, P.; Weber, W.; Rossmann, C. Gesundheitsinformationsverhalten 65+: Erreichbarkeit Älterer Zielgruppen. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2021, 64, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridman, I.; Ubel, P.A.; Kahn, V.C.; Fagerlin, A. Association of Quantitative Information and Patient Knowledge about Prostate Cancer Outcomes. Health Psychol. 2022, 41, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.G.; Reissmann, M.E.; Parkhomenko, E.; Wang, D.S. Evaluating the Quality of Online Health Information about Prostate Cancer Treatment. Urol. Pr. 2021, 8, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| All (n = 508) | ORP (n = 201) | RARP (n = 307) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 64.8 ± 6.9 65 (45–80) | 64.5 ± 6.7 65 (45–77) | 65.0 ± 7.0 66 (45–80) | 0.5 * |

| D’Amico classification | ||||

| Low risk | 78 (15%) | 29 (14%) | 49 (16%) | <0.001 |

| Intermediate risk | 313 (62%) | 97 (48%) | 216 (70%) | |

| High risk | 117 (23%) | 75 (37%) | 42 (14%) | |

| Insurance status (n = 485) | ||||

| Statutory | 351 (77%) | 154 (81%) | 197 (67%) | <0.001 |

| Private | 134 (29%) | 35 (19%) | 99 (33%) | |

| Living area (n = 494) | ||||

| Rural | 239 (48%) | 101 (51%) | 138 (47%) | 0.3 |

| City | 255 (52%) | 97 (49%) | 158 (53%) | |

| Marital status (n = 494) | ||||

| not Married | 52 (11%) | 20 (10%) | 32 (11%) | 0.9 |

| Married | 442 (89%) | 176 (90%) | 266 (89%) | |

| Educational degree (n = 446) | ||||

| None | 1 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 0.02 |

| Lower secondary school | 113 (25%) | 56 (33%) | 57 (21%) | |

| Secondary school | 156 (35%) | 58 (34%) | 98 (36%) | |

| High school | 176 (39%) | 57 (33%) | 119 (43%) | |

| Net income/m in EUR (n = 456) | ||||

| <1500 | 35 (8%) | 22 (12%) | 13 (5%) | 0.002 |

| 1500–4000 | 276 (61%) | 115 (63%) | 161 (59%) | |

| >4000 | 145 (32%) | 46 (25%) | 99 (36%) | |

| Study centre | ||||

| 1 | 167 (33%) | 44 (22%) | 123 (40%) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 49 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 49 (16%) | |

| 3 | 49 (10%) | 49 (24%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 4 | 93 (18%) | 28 (14%) | 65 (21%) | |

| 5 | 53 (10%) | 13 (6%) | 40 (13%) | |

| 6 | 55 (11%) | 55 (27%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 7 | 42 (8%) | 12 (6%) | 30 (10%) | |

| All (n = 508) | ORP (n = 201) | RARP (n = 307) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information acquisition on RP (n = 388) | ||||

| More on RARP | 75 (17%) | 6 (4%) | 69 (26%) | <0.001 |

| Equally | 267 (62%) | 82 (49%) | 185 (70%) | |

| More on ORP | 90 (21%) | 80 (48%) | 10 (4%) | |

| Internet usage for health-related topics (n = 490) | ||||

| Daily | 20 (4%) | 8 (4%) | 12 (4%) | 0.2 |

| 1/week | 86 (18%) | 28 (15%) | 58 (20%) | |

| Less than 1/week | 314 (64%) | 123 (64%) | 191 (64%) | |

| Not at all | 70 (14%) | 34 (18%) | 36 (12%) | |

| Online sources used | ||||

| Video platforms | 7 (1%) | 4 (2%) | 3 (1%) | n.a. |

| Social media | 20 (4%) | 8 (4%) | 12 (4%) | |

| Expert association | 60 (12%) | 24 (12%) | 36 (12%) | |

| Online press | 62 (12%) | 20 (10%) | 42 (14%) | |

| Wikipedia | 67 (13%) | 29 (14%) | 38 (12%) | |

| Online fora | 96 (19%) | 40 (20%) | 56 (18%) | |

| Others | 127 (25%) | 55 (27%) | 72 (23%) | |

| None | 12 (3%) | 6 (3%) | 6 (2%) | |

| Decisional behaviour general (n = 476) | ||||

| Self-sufficient | 12 (3%) | 6 (3%) | 6 (2%) | 0.2 |

| Considering experts’ opinion | 140 (29%) | 48 (25%) | 92 (32%) | |

| Jointly | 289 (61%) | 116 (61%) | 173 (60%) | |

| Considering own opinion | 31 (7%) | 17 (9%) | 14 (5%) | |

| Doctors’ decision | 4 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | |

| Decisional behaviour regarding surgical procedure (n = 457) | ||||

| Self-sufficient | 59 (13%) | 14 (8%) | 45 (16%) | <0.001 |

| Considering experts’ opinion | 130 (28%) | 42 (24%) | 88 (31%) | |

| Jointly | 190 (42%) | 75 (43%) | 115 (41%) | |

| Considering own opinion | 52 (11%) | 23 (13%) | 29 (10%) | |

| Doctors’ decision | 26 (6%) | 20 (11%) | 6 (2%) | |

| Decisional behaviour regarding performing centre (n = 482) | ||||

| Self-sufficient | 127 (26%) | 52 (27%) | 75 (26%) | 0.3 |

| Considering experts’ opinion | 96 (20%) | 36 (19%) | 60 (21%) | |

| Jointly | 168 (35%) | 61 (32%) | 107 (37%) | |

| Considering own opinion | 42 (9%) | 23 (12%) | 19 (7%) | |

| Doctors’ decision | 49 (10%) | 18 (9%) | 31 (11%) | |

| Univariable Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | p Value | OR | p Value | |

| Old age (66+) | 2.0 (1.2–3.3) | 0.007 | 2.1 (1.1–3.9) | 0.02 |

| No high school degree | 1.8 (1,1–3.1) | 0.02 | 1.9 (1.0–3.6) | 0.047 |

| Paternalistic/partially paternalistic decisional behaviour | 1.2 (0.8–2.0) | 0.4 | 1.5 (0.8–2.8) | 0.3 |

| Unbalanced information acquisition | 2.9 (1.6–5.1) | <0.001 | 2.4 (1.2–5.1) | 0.02 |

| RARP patient | 1.9 (1.1–3.2) | 0.02 | 8.9 (3.3–23.8) | <0.001 |

| No choice of procedure at centre | 1.7 (1.2–2.4) | 0.002 | 3.5 (2.0–6.1) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hirtsiefer, C.; Vogelgesang, A.; Falkenbach, F.; Kafka, M.; Uhlig, A.; Nestler, T.; Aksoy, C.; Simunovic, I.; Huber, J.; Heidegger, I.; et al. Information Behaviour and Knowledge of Patients Before Radical Prostatectomy. Cancers 2025, 17, 300. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17020300

Hirtsiefer C, Vogelgesang A, Falkenbach F, Kafka M, Uhlig A, Nestler T, Aksoy C, Simunovic I, Huber J, Heidegger I, et al. Information Behaviour and Knowledge of Patients Before Radical Prostatectomy. Cancers. 2025; 17(2):300. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17020300

Chicago/Turabian StyleHirtsiefer, Christopher, Anna Vogelgesang, Fabian Falkenbach, Mona Kafka, Annemarie Uhlig, Tim Nestler, Cem Aksoy, Iva Simunovic, Johannes Huber, Isabel Heidegger, and et al. 2025. "Information Behaviour and Knowledge of Patients Before Radical Prostatectomy" Cancers 17, no. 2: 300. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17020300

APA StyleHirtsiefer, C., Vogelgesang, A., Falkenbach, F., Kafka, M., Uhlig, A., Nestler, T., Aksoy, C., Simunovic, I., Huber, J., Heidegger, I., Graefen, M., Leitsmann, M., Thomas, C., & Baunacke, M. (2025). Information Behaviour and Knowledge of Patients Before Radical Prostatectomy. Cancers, 17(2), 300. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17020300