Expert Judgment Supporting a Bayesian Network to Model the Survival of Pancreatic Cancer Patients †

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pilot Eliciting Protocol

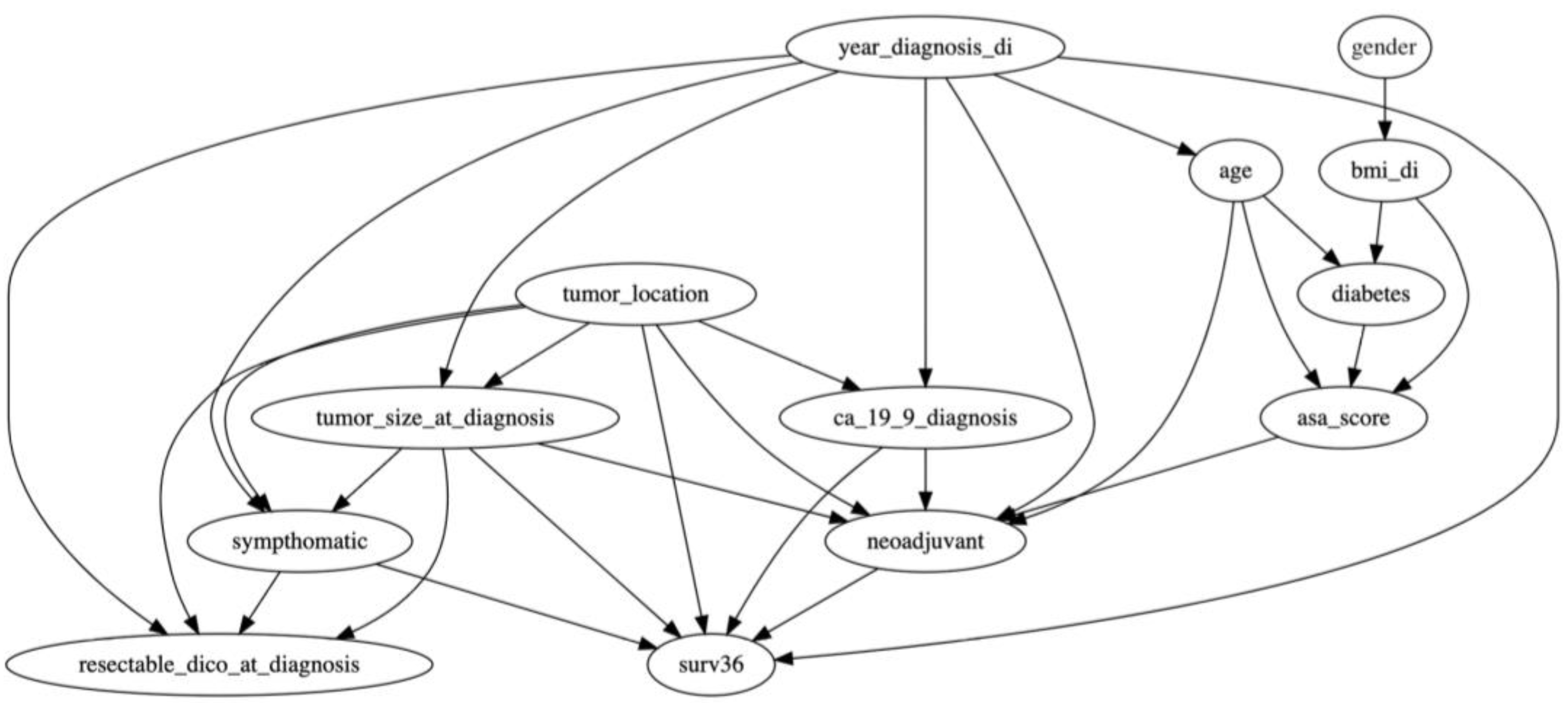

2.2. Hybrid BN Design

- −

- CA19.9 serum levels at diagnosis (continuous; expressed as UI/mL);

- −

- Gender (categorical dichotomous; male vs. female);

- −

- Body mass index (BMI; categorical dichotomous; normal/overweight [BMI ≤ 30] vs. obesity [BMI > 30, Kg/m2]);

- −

- Year of diagnosis (categorical dichotomous; before 31 December 2014 vs. after 1 January 2015, given the introduction of FOLFIRINOX chemotherapy to clinical practice);

- −

- Tumor location (categorical dichotomous; head vs. body/tail);

- −

- Age (continuous; expressed in years);

- −

- Diabetes (categorical dichotomous; presence vs. absence of diabetes);

- −

- Tumor size (continuous; expressed in millimeters);

- −

- Symptoms (categorical dichotomous; symptomatic vs. no symptoms);

- −

- American Association of Anesthesiology (ASA) Score [20] (categorical dichotomous; ASA I–II vs. ASA III–IV);

- −

- Resectability status (categorical dichotomous; resectable PDAC vs. borderline resectable/locally advanced PDAC according to NCCN criteria, version 2.2021) [21];

- −

- Neoadjuvant treatment (categorical dichotomous; neoadjuvant treatment performed vs. non-performed).

2.3. Elicitation Process—The SHELF Method

2.4. Handling of QoIs

2.5. Selection of Experts

2.6. Pooling Expert Opinions

3. Results

- For continuous variables like CA 19-9 serum levels or tumor size, the prior distribution provides a range of plausible values based on clinical experience. This influences the BN’s estimation of survival outcomes for patients with varying CA 19-9 serum levels.

- For categorical variables such as gender, the prior distribution reflects the expected population proportion of male versus female patients, setting an initial baseline for the BN. For example, the probability distribution shown for gender, which lies mostly between 0.5 and 0.6, represents the experts’ pooled estimate of the proportion of male patients among this model’s total population of pancreatic cancer cases. In this case, a value of 0.5 to 0.6 indicates a slight prevalence of one gender over the other, with the probability reflecting the anticipated proportion based on clinical observations or available demographic data.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcinak, C.T.; Parker, W.F.; Parikh, A.A.; Datta, J.; Maithel, S.K.; Kooby, D.A.; Burkard, M.E.; Kim, H.J.; LeCompte, M.T.; Afshar, M.; et al. Accuracy of models to prognosticate survival after surgery for pancreatic cancer in the era of neoadjuvant therapy. J. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 128, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Placido, D.; Yuan, B.; Hjaltelin, J.X.; Zheng, C.; Haue, A.D.; Chmura, P.J.; Yuan, C.; Kim, J.; Umeton, R.; Antell, G.; et al. A deep learning algorithm to predict risk of pancreatic cancer from disease trajectories. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 1113–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Park, T.; Jang, J.; Lee, S. Comparison of survival prediction models for pancreatic cancer: Cox model versus machine learning models. Genom. Inform. 2022, 20, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verduijn, M.; Peek, N.; Rosseel, P.M.; de Jonge, E.; de Mol, B.A. Prognostic Bayesian networks I: Rationale, learning procedure, and clinical use. J. Biomed. Inform. 2007, 40, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, S.; Speed, T.P. Network inference using informative priors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 14313–14318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuan, L.; Greiner, R. Using Discrete Hazard Bayesian Networks to Identify which Features are Relevant at each Time in a Survival Prediction Model. Proceeding Mach. Learn. Res. 2021, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, A.; Van der Meer, R.; McKay, C.J. A prognostic Bayesian network that makes personalized predictions of poor prognostic outcome post resection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.-Y.; Morgan, J.; Soley-Bori, M.; Min, K. Bayesian Statistics; Boston University: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNair, D.S.; Simpson, R.L. Bayesian Cost-effectiveness Analysis of Falls Risk Assessment Tools: Falls: Sensitivity and Specificity-Asking for Decision Support Changes? Nurs. Adm. Q. 2016, 40, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, D.; Cope, S.; Towle, K.; Mojebi, A.; Marshall, T.; Dhanda, D. Structured expert elicitation to inform long-term survival extrapolations using alternative parametric distributions: A case study of CAR T therapy for relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2022, 22, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzhauer, B.; Hampson, L.V.; Gosling, J.P.; Bornkamp, B.; Kahn, J.; Lange, M.R.; Luo, W.L.; Brindicci, C.; Lawrence, D.; Ballerstedt, S.; et al. Eliciting judgements about dependent quantities of interest: The SHeffield ELicitation Framework extension and copula methods illustrated using an asthma case study. Pharm. Stat. 2022, 21, 1005–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallow, N.; Best, N.; Montague, T.H. Better decision making in drug development through adoption of formal prior elicitation. Pharm. Stat. 2018, 17, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barons, M.J.; Mascaro, S.; Hanea, A.M. Balancing the Elicitation Burden and the Richness of Expert Input When Quantifying Discrete Bayesian Networks. Risk Anal. 2022, 42, 1196–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, A.J.; Thomas, M.K.; Pintar, K.D. Systematic review of expert elicitation methods as a tool for source attribution of enteric illness. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2015, 12, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, R.M.; Wilson, A.M.; Tuomisto, J.T.; Morales, O.; Tainio, M.; Evans, J.S. A probabilistic characterization of the relationship between fine particulate matter and mortality: Elicitation of European experts. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 6598–6605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, J.; O’Hagan, A. The Sheffield Elicitation Framework (Version 2.0). Available online: http://tonyohagan.co.uk/shelf (accessed on 13 March 2022).

- O’Hagan, A. Expert Knowledge Elicitation: Subjective but Scientific. Am. Stat. 2019, 73, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, G.S.; Reitsma, J.B.; Altman, D.G.; Moons, K.G. Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): The TRIPOD statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2015, 162, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouleish, A.E.; Leib, M.L.; Cohen, N.H. ASA Provides Examples to Each ASA Physical Status Class. ASA Newsl. 2015, 79, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tempero, M.A.; Malafa, M.P.; Al-Hawary, M.; Behrman, S.W.; Benson, A.B.; Cardin, D.B.; Chiorean, E.G.; Chung, V.; Czito, B.; Del Chiaro, M.; et al. Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma, Version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2021, 19, 439–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Dalton, J.; Nutter, B. Working with HydeNetwork Objects. 2020.

- Dalton, J.; Nutter, B. Decision Network (Influence Diagram) Analyses in HydeNet. Available online: http://cran.nexr.com/web/packages/HydeNet/vignettes/DecisionNetworks.html (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Morgan, M.G. Use (and abuse) of expert elicitation in support of decision making for public policy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 7176–7184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hagan, A. Eliciting Expert Beliefs in Substantial Practical Applications. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. D 1998, 47, 21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, D.; Oakley, J.; Crowe, J. A web-based tool for eliciting probability distributions from experts. Environ. Model. Softw. 2014, 52, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, N.M. Incentive-Compatible Elicitation of Quantiles. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1611.00868. [Google Scholar]

- Aupiais, C.; Alberti, C.; Schmitz, T.; Baud, O.; Ursino, M.; Zohar, S. A Bayesian non-inferiority approach using experts’ margin elicitation—Application to the monitoring of safety events. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2019, 19, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, J.O.; Wang, H.; Holcomb, J.B.; Harvin, J.A.; Richman, J.; Avritscher, E.; Stephens, S.W.; Truong, V.T.T.; Marques, M.B.; DeSantis, S.M.; et al. Elicitation of prior probability distributions for a proposed Bayesian randomized clinical trial of whole blood for trauma resuscitation. Transfusion 2020, 60, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietbergen, C.; Klugkist, I.; Janssen, K.J.; Moons, K.G.; Hoijtink, H.J. Incorporation of historical data in the analysis of randomized therapeutic trials. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2011, 32, 848–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnersley, N.; Day, S. Structured approach to the elicitation of expert beliefs for a Bayesian-designed clinical trial: A case study. Pharm. Stat. 2013, 12, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovers, M.M.; van der Wilt, G.J.; van der Bij, S.; Straatman, H.; Ingels, K.; Zielhuis, G.A. Bayes’ theorem: A negative example of a RCT on grommets in children with glue ear. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2005, 20, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Principe, D.R.; Underwood, P.W.; Korc, M.; Trevino, J.G.; Munshi, H.G.; Rana, A. The Current Treatment Paradigm for Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma and Barriers to Therapeutic Efficacy. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 688377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groot, V.P.; Gemenetzis, G.; Blair, A.B.; Rivero-Soto, R.J.; Yu, J.; Javed, A.A.; Burkhart, R.A.; Rinkes, I.; Molenaar, I.Q.; Cameron, J.L.; et al. Defining and Predicting Early Recurrence in 957 Patients With Resected Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Ann. Surg. 2019, 269, 1154–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, M.F.; Kattan, M.W.; Klimstra, D.; Conlon, K. Prognostic nomogram for patients undergoing resection for adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Ann. Surg. 2004, 240, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, D.; Weng, C. Combining PubMed knowledge and EHR data to develop a weighted bayesian network for pancreatic cancer prediction. J. Biomed. Inform. 2011, 44, 859–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzolina, D.; Berchialla, P.; Bressan, S.; Da Dalt, L.; Gregori, D.; Baldi, I. A Bayesian Sample Size Estimation Procedure Based on a B-Splines Semiparametric Elicitation Method. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Nodes | Mean | SD | Best-Fit Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ca 19.9 values | 130.29 | 207.84 | T (130.29, 207.84, df = 7 ***) |

| Age (years) * | 69.49 | 15.69 | MirrorlogT (69.49, 15.69, df = 6) |

| Tumor size (mm) ** | 23.86 | 11.42 | MirrorlogT (23.74, 11.45, df = 7) |

| Gender | 0.56 | 0.13 | Beta (7.62, 5.76) |

| Body mass index (normal/overweight–obese) | 0.59 | 0.11 | Beta (10.07, 6.69) |

| Year of diagnosis (before 31 December 2014) | 0.65 | 0.65 | Beta (3.85, 2.08) |

| Tumor location (head) | 0.54 | 0.17 | Beta (4.26, 3.63) |

| Diabetes (absence) | 0.58 | 0.11 | Beta (12.52, 10.00) |

| Symptoms (absence) | 0.61 | 0.19 | Beta (3.46, 2.15) |

| American Association of Anesthesiology (ASA) Score I–II | 0.62 | 0.16 | Beta (4.75, 2.94) |

| Resectability at diagnosis | 0.64 | 0.18 | Beta (3.83, 2.13) |

| Neoadjuvant treatment | 0.61 | 0.19 | Beta (3.46, 2.22) |

| Nodes | Expert Best-Fit Distribution | Type of Prevalent Distribution (Number of Experts with Prevalent Distribution/Number of Experts) |

|---|---|---|

| Ca 19.9 values |  | T (6/8) |

| Age (years) |  | MirrorlogT (4/7) |

| Tumor size (mm) |  | MirrorlogT (8/8) |

| Gender |  | LogT (6/9) |

| Body mass index (normal/overweight–obese) |  | LogT (6/9) |

| Year of diagnosis (before 31 December 2014) |  | LogT (5/9) |

| Tumor location (head) |  | MirrorlogT (6/9) |

| Diabetes (absence) |  | Normal (6/9) |

| Symptoms (absence) |  | MirrorlogT (5/9) |

| American Association of Anesthesiology (ASA) Score I–II |  | LogT (9/9) |

| Resectability at diagnosis |  | MirrorlogT (7/9) |

| Neoadjuvant treatment |  | MirrorlogT (6/9) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Secchettin, E.; Paiella, S.; Azzolina, D.; Casciani, F.; Salvia, R.; Malleo, G.; Gregori, D. Expert Judgment Supporting a Bayesian Network to Model the Survival of Pancreatic Cancer Patients. Cancers 2025, 17, 301. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17020301

Secchettin E, Paiella S, Azzolina D, Casciani F, Salvia R, Malleo G, Gregori D. Expert Judgment Supporting a Bayesian Network to Model the Survival of Pancreatic Cancer Patients. Cancers. 2025; 17(2):301. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17020301

Chicago/Turabian StyleSecchettin, Erica, Salvatore Paiella, Danila Azzolina, Fabio Casciani, Roberto Salvia, Giuseppe Malleo, and Dario Gregori. 2025. "Expert Judgment Supporting a Bayesian Network to Model the Survival of Pancreatic Cancer Patients" Cancers 17, no. 2: 301. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17020301

APA StyleSecchettin, E., Paiella, S., Azzolina, D., Casciani, F., Salvia, R., Malleo, G., & Gregori, D. (2025). Expert Judgment Supporting a Bayesian Network to Model the Survival of Pancreatic Cancer Patients. Cancers, 17(2), 301. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17020301