Axillary Overtreatment in Patients with Breast Cancer After Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in the Current Era of Targeted Axillary Dissection

Abstract

Highlights

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

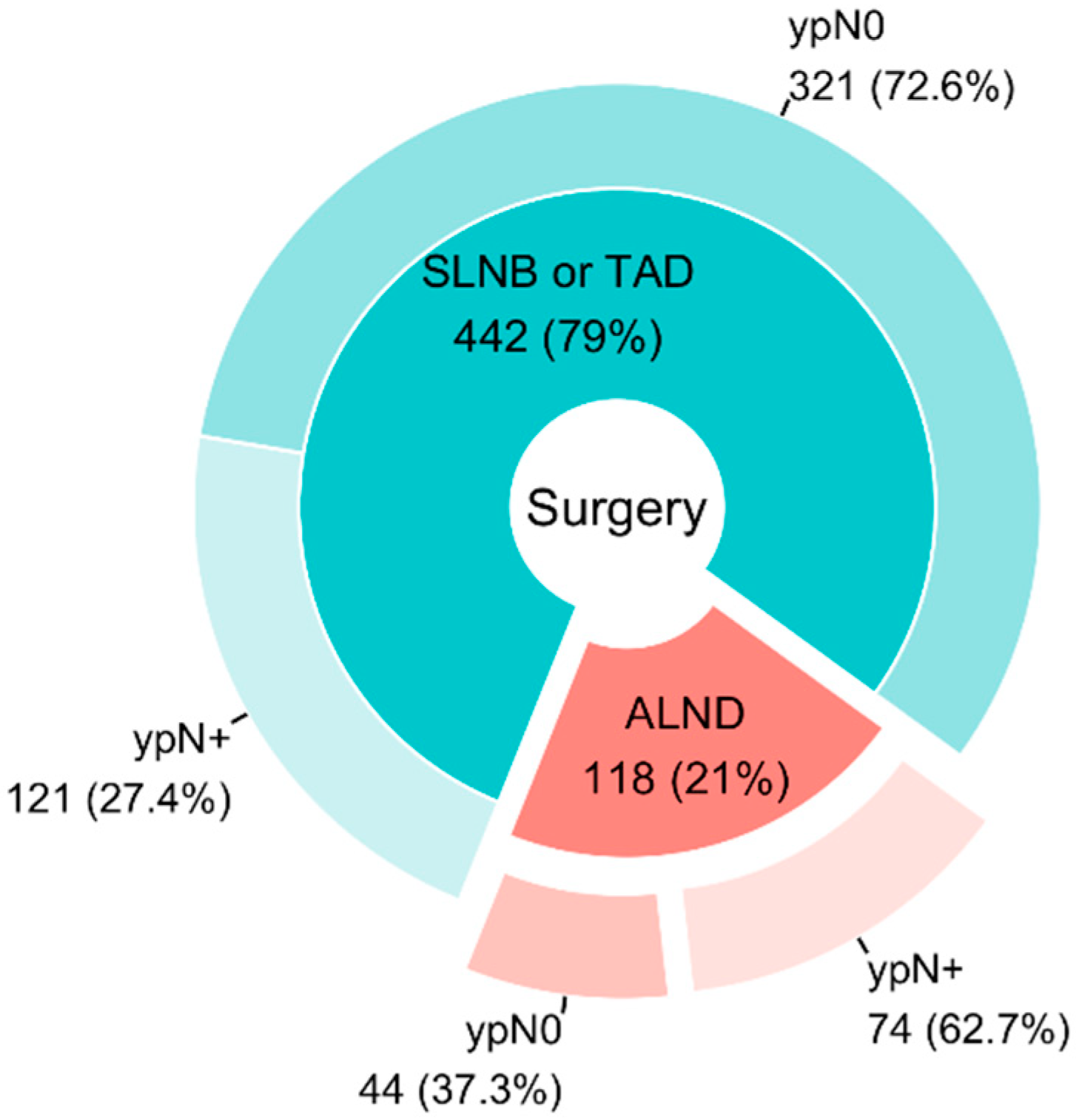

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NAC | Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy |

| TAD | Targeted Axillary Dissection |

| ALND | Axillary Lymph Node Dissection |

| SLNB | Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy |

| FNR | False-Negative Rate |

| US | Ultrasound |

| RT | Radiotherapy |

| HER2 | Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 |

| TNBC | Triple-Negative Breast Cancer |

References

- Geng, C.; Chen, X.; Pan, X.; Li, J. The Feasibility and Accuracy of Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy in Initially Clinically Node-Negative Breast Cancer after Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0162605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boughey, J.C.; Suman, V.J.; Mittendorf, E.A.; Ahrendt, G.M.; Wilke, L.G.; Taback, B.; Leitch, A.M.; Kuerer, H.M.; Bowling, M.; Flippo-Morton, T.S.; et al. Sentinel lymph node surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with node-positive breast cancer: The ACOSOG Z1071 (Alliance) clinical trial. JAMA 2013, 310, 1455–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuehn, T.; Bauerfeind, I.; Fehm, T.; Fleige, B.; Hausschild, M.; Helms, G.; Lebeau, A.; Liedtke, C.; von Minckwitz, G.; Nekljudova, V.; et al. Sentinel-lymph-node biopsy in patients with breast cancer before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (SENTINA): A prospective, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caudle, A.S.; Yang, W.T.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Mittendorf, E.A.; Black, D.M.; Gilcrease, M.Z.; Bedrosian, I.; Hobbs, B.P.; DeSnyder, S.M.; Hwang, R.F.; et al. Improved Axillary Evaluation Following Neoadjuvant Therapy for Patients With Node-Positive Breast Cancer Using Selective Evaluation of Clipped Nodes: Implementation of Targeted Axillary Dissection. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 1072–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swarnkar, P.K.; Tayeh, S.; Michell, M.J.; Mokbel, K. The Evolving Role of Marked Lymph Node Biopsy (MLNB) and Targeted Axillary Dissection (TAD) after Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy (NACT) for Node-Positive Breast Cancer: Systematic Review and Pooled Analysis. Cancers 2021, 13, 1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Guidelines. Breast Cancer (Version 1.2024). Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast_blocks.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2024).

- Polgár, C.; Kahán, Z.; Ivanov, O.; Chorváth, M.; Ligačová, A.; Csejtei, A.; Gábor, G.; Landherr, L.; Mangel, L.; Mayer, Á.; et al. Radiotherapy of Breast Cancer-Professional Guideline 1st Central-Eastern European Professional Consensus Statement on Breast Cancer. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2022, 28, 1610378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banys-Paluchowski, M.; Gasparri, M.L.; de Boniface, J.; Gentilini, O.; Stickeler, E.; Hartmann, S.; Thill, M.; Rubio, I.T.; Di Micco, R.; Bonci, E.-A.; et al. Surgical Management of the Axilla in Clinically Node-Positive Breast Cancer Patients Converting to Clinical Node Negativity through Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy: Current Status, Knowledge Gaps, and Rationale for the EUBREAST-03 AXSANA Study. Cancers 2021, 13, 1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Žatecký, J.; Coufal, O.; Zapletal, O.; Kubala, O.; Kepičová, M.; Faridová, A.; Rauš, K.; Gatěk, J.; Kosáč, P.; Peteja, M. Ideal marker for targeted axillary dissection (IMTAD): A prospective multicentre trial. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 21, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Loevezijn, A.A.; van der Noordaa, M.E.M.; Stokkel, M.P.M.; van Werkhoven, E.D.; Groen, E.J.; Loo, C.E.; Elkhuizen, P.H.M.; Sonke, G.S.; Russell, N.S.; van Duijnhoven, F.H.; et al. Three-year follow-up of de-escalated axillary treatment after neoadjuvant systemic therapy in clinically node-positive breast cancer: The MARI-protocol. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2022, 193, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coufal, O.; Zapletal, O.; Gabrielová, L.; Fabian, P.; Schneiderová, M. Targeted axillary dissection and sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer patients after neoadjuvant chemotherapy—A retrospective study. Rozhl. Chir. 2018, 97, 551–557. [Google Scholar]

- C of A Pathologists. Protocol for the Examination of Resection Specimens from Patients with Invasive Carcinoma of the Breast Version: 4.9.0.1. Available online: https://documents.cap.org/protocols/Breast.Invasive_4.9.0.1.REL_CAPCP.pdf?_gl=1*1rfpnry*_ga*MjQ2NzI5MzQ0LjE2MTE4MjI4OTg.*_ga_97ZFJSQQ0X*MTcwNzIyMDAyOC4yNi4wLjE3MDcyMjAwMjkuMC4wLjA (accessed on 8 January 2024).

- Samiei, S.; Simons, J.M.; Engelen, S.M.; Beets-Tan, R.G.; Classe, J.M.; Smidt, M.L.; Eubreast Group. Axillary Pathologic Complete Response After Neoadjuvant Systemic Therapy by Breast Cancer Subtype in Patients With Initially Clinically Node-Positive Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Surg. 2021, 156, e210891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samiei, S.; van Nijnatten, T.J.A.; de Munck, L.; Keymeulen, K.B.M.I.; Simons, J.M.; Kooreman, L.F.S.; Siesling, S.; Lobbes, M.B.I.; Smidt, M.L. Correlation Between Pathologic Complete Response in the Breast and Absence of Axillary Lymph Node Metastases After Neoadjuvant Systemic Therapy. Ann. Surg. 2020, 271, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brierley, J.D.; Gospodarowicz, M.K.; Wittekind, C. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours, 8th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Goetz, M.P.; Gradishar, W.J.; Anderson, B.O.; Abraham, J.; Aft, R.; Allison, K.H.; Blair, S.L.; Burstein, H.J.; Dang, C.; Elias, A.D.; et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Breast Cancer, Version 3.2018. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2019, 17, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeSnyder, S.M.; Mittendorf, E.A.; Le-Petross, C.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Whitman, G.J.; Ueno, N.T.; Woodward, W.A.; Kuerer, H.M.; Akay, C.L.; Babiera, G.V.; et al. Prospective Feasibility Trial of Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy in the Setting of Inflammatory Breast Cancer. Clin. Breast Cancer 2018, 18, e73–e77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanlik, H.; Cabioglu, N.; Oprea, A.L.; Ozgur, I.; Ak, N.; Aydiner, A.; Onder, S.; Bademler, S.; Gulluoglu, B.M. Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy May Prevent Unnecessary Axillary Dissection in Patients with Inflammatory Breast Cancer Who Respond to Systemic Treatment. Breast Care 2021, 16, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leinert, E.; Lukac, S.; Schwentner, L.; Coenen, A.; Fink, V.; Veselinovic, K.; Dayan, D.; Janni, W.; Friedl, T.W. The use of axillary ultrasound (AUS) to assess the nodal status after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) in primary breast cancer patients. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 52, 102016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pislar, N.; Gasljevic, G.; Music, M.M.; Borstnar, S.; Zgajnar, J.; Perhavec, A. Axillary ultrasound for predicting response to neoadjuvant treatment in breast cancer patients-a single institution experience. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 21, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontos, M.; Kanavidis, P.; Kühn, T.; Masannat, Y.; Gulluoglu, B.; TAD Study Group. Targeted axillary dissection: Worldwide variations in clinical practice. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2024, 204, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, S.; Sabel, M.S.; Hughes, T.M.; Chang, A.E.; Dossett, L.A.; Jeruss, J.S. Impact of Breast Cancer Pretreatment Nodal Burden and Disease Subtype on Axillary Surgical Management. J. Surg. Res. 2021, 261, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinterri, C.; Barbieri, E.; Sagona, A.; Di Maria Grimaldi, S.; Gentile, D. De-Escalation of Axillary Surgery in Clinically Node-Positive Breast Cancer Patients Treated with Neoadjuvant Therapy: Comparative Long-Term Outcomes of Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy versus Axillary Lymph Node Dissection. Cancers 2024, 16, 3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B.L.; Collier, A.L.; Kelly, K.N.; Goel, N.; Kesmodel, S.B.; Yakoub, D.; Moller, M.; Avisar, E.; Franceschi, D.; Macedo, F.I. Surgical Management of the Axilla in Patients with Occult Breast Cancer (cT0 N+) After Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 27, 1830–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total (n = 118) | ypN0 (n = 44) | ypN+ (n = 74) | OR (95% CI) | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Median (range) | 55 (27, 85) | 56 (27, 78) | 54 (29, 85) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.04) | 0.344 | |

| cT | T1 | 13 (11%) | 7 (54%) | 6 (46%) | 1.86 (0.43, 8.27) | 0.405 |

| T2 | 48 (41%) | 12 (25%) | 36 (75%) | 6.50 (2.10, 22.3) | 0.002 | |

| T3 | 17 (14%) | 6 (35%) | 11 (65%) | 3.97 (1.03, 17.0) | 0.051 | |

| T4b | 18 (15%) | 4 (22%) | 14 (78%) | 7.58 (1.87, 37.0) | 0.007 | |

| T4d | 19 (16%) | 13 (68%) | 6 (32%) | Ref | ||

| TX | 3 (2.5%) | 2 (67%) | 1 (33%) ⌂ | NS | ||

| cN | * N0/1 | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) | NS | |

| N1 | 93 (79%) | 38 (41%) | 55 (59%) | Ref | ||

| N2 | 14 (12%) | 1 (7.1%) | 13 (93%) | 8.98 (1.68, 167) | 0.038 | |

| N3 | 10 (8.5%) | 5 (50%) | 5 (50%) | 0.69 (0.18, 2.64) | 0.579 | |

| Phenotype | Luminal A | 4 (3.4%) | 1 (25%) □ | 3 (75%) | 9.60 (0.99, 221) | 0.073 |

| Luminal B HER2 negative | 33 (28%) | 1 (3.0%) # | 32 (97%) | 102 (15.9, 2073) | <0.001 | |

| Luminal B HER2 positive | 18 (15%) | 8 (44%) | 10 (56%) | 4.00 (1.06, 16.9) | 0.047 | |

| ** Luminal B HER2 positive/negative | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) | NS | ||

| Non-luminal HER2 positive | 21 (18%) | 16 (76%) | 5 (24%) | Ref | ||

| Triple-negative breast cancer | 41 (35%) | 18 (44%) | 23 (56%) | 4.09 (1.32, 14.5) | 0.019 | |

| Type of breast surgery | Breast-conserving surgery | 30 (25%) | 7 (23%) | 23 (77%) | Ref | |

| Mastectomy | 87 (74%) | 36 (41%) | 51 (59%) | 0.43 (0.16, 1.07) | 0.082 | |

| No surgery | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (100%) | 0 (0%) | |||

| ypT | ypT0 | 29 (25%) | 22 (76%) | 7 (24%) | Ref | |

| ypTis | 12 (10%) | 8 (67%) | 4 (33%) | |||

| ypT1 | 38 (32%) | 10 (26%) | 28 (74%) | 7.64 (2.91, 21.7) | <0.001 | |

| ypT2 | 27 (23%) | 0 (0%) | 27 (100%) | 46.4 (11.6, 317) | <0.001 | |

| ypT3 | 4 (3.4%) | 1 (25%) | 3 (75%) | |||

| ypT4b | 5 (4.2%) | 1 (20%) | 4 (80%) | |||

| X | 3 (2.5%) | 2 (67%) | 1 (33%) | NS | ||

| Number of examined lymph nodes Median (range) | 12 (1, 37) | 11 (1, 37) | 12 (5, 30) | 1.07 (1.0, 1.17) | 0.086 | |

| Reason for ALND | Number of Cases |

|---|---|

| Inflammatory carcinoma | 13 (29.5%) |

| Persistent pathological nodes on re-staging US examination | 8 (18.2%) |

| Participation in a drug clinical trial | 6 (13.6%) |

| Combination of multiple “minor” factors | 6 (13.6%) |

| Locally advanced breast cancer (LABC) at initial presentation (T4bN2, T4bN1, T3N2, T3N3, T2N3) | 5 (11.4%) |

| Occult carcinoma (supported by re-staging ultrasound examination) | 2 (4.5%) |

| Contraindications to adjuvant radiotherapy | 2 (4.5%) |

| Misinterpretation of ultrasound examination | 2 (4.5%) |

| Total | 44 (100%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zapletal, O.; Žatecký, J.; Gabrielová, L.; Selingerová, I.; Holánek, M.; Burkoň, P.; Coufal, O. Axillary Overtreatment in Patients with Breast Cancer After Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in the Current Era of Targeted Axillary Dissection. Cancers 2025, 17, 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17020178

Zapletal O, Žatecký J, Gabrielová L, Selingerová I, Holánek M, Burkoň P, Coufal O. Axillary Overtreatment in Patients with Breast Cancer After Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in the Current Era of Targeted Axillary Dissection. Cancers. 2025; 17(2):178. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17020178

Chicago/Turabian StyleZapletal, Ondřej, Jan Žatecký, Lucie Gabrielová, Iveta Selingerová, Miloš Holánek, Petr Burkoň, and Oldřich Coufal. 2025. "Axillary Overtreatment in Patients with Breast Cancer After Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in the Current Era of Targeted Axillary Dissection" Cancers 17, no. 2: 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17020178

APA StyleZapletal, O., Žatecký, J., Gabrielová, L., Selingerová, I., Holánek, M., Burkoň, P., & Coufal, O. (2025). Axillary Overtreatment in Patients with Breast Cancer After Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in the Current Era of Targeted Axillary Dissection. Cancers, 17(2), 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17020178