Beyond Visualization: Advanced Imaging, Theragnostics and Biomarker Integration in Urothelial Bladder Cancer

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

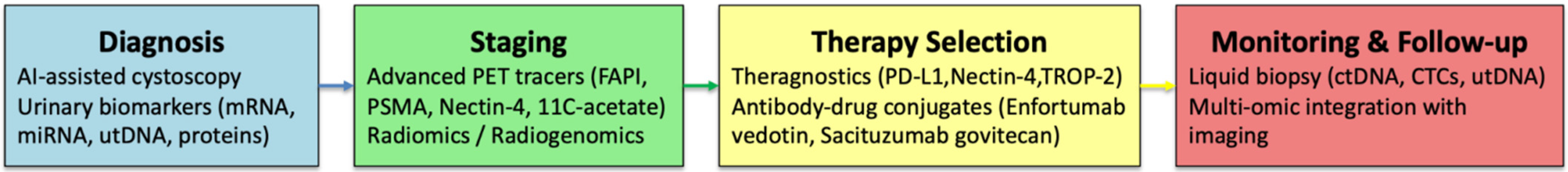

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Advances in Molecular Imaging and Emerging PET Tracers in Bladder Cancer

3.1.1. Fibroblast Activation Protein Inhibitors (FAPI)

3.1.2. Alternative Modalities and Computational Tools

- [11C]-Acetate PET/Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): The ACEBIB trial evaluated Carbon-11-labeled acetate ([11C]-acetate) PET/MRI as an alternative tracer for staging and treatment monitoring in bladder cancer. [11C]-acetate targets lipid metabolism, which is upregulated in many tumors, and offers the advantage of minimal urinary excretion compared to FDG, reducing interference in bladder imaging. In this multicenter study, the technique achieved 100% sensitivity for detecting muscle-invasive disease and showed reasonable correlation with response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. However, its sensitivity for nodal metastases was limited (20%), underscoring the need for further validation before clinical adoption [12].

- AI applied to PET/FDG: To improve the limited accuracy of FDG PET/CT in nodal staging, machine learning has been explored as a complementary tool. In one study, a random forest model was developed using three objective parameters—Maximum Standardized Uptake Value (SUVmax) of the most avid lymph node, product of diameters of the largest node, and primary tumor size. This model achieved higher diagnostic accuracy than expert consensus in the training cohort (area under curve (AUC) 0.87 vs. 0.73; p = 0.048). Although performance did not hold in the independent validation set (AUC 0.59 vs. 0.64; p = 0.54), interrater agreement was excellent (kappa = 0.66), suggesting that AI-based approaches could provide reproducible, standardized support for lymph node assessment in muscle-invasive bladder cancer [13].

3.1.3. Emerging Molecular Targets for Imaging

3.1.4. Nectin-4-Targeted Imaging

3.2. Enhanced Cystoscopic Evaluation Through AI and Optical Imaging

3.2.1. Advances in Optical Imaging and the Role of AI

3.2.2. AI-Based Detection and Real-Time Imaging

3.2.3. Tumor Segmentation and Dual-Function Models

3.2.4. Grading, Biological Behavior, and Real-Time Augmentation

3.3. Experimental Theragnostic Approaches in Bladder Cancer

3.3.1. From Immunotherapy to Immuno-Theragnostics

3.3.2. Immune-Related Targets

3.3.3. Nectin-4 and TROP-2: Companion Diagnostics and Antibody-Drug Conjugates

3.4. Liquid Biopsy and Circulating Biomarkers

3.4.1. CTCs

3.4.2. ctDNA

3.4.3. RNA Biomarkers

- mRNA-based assays: Several commercial urine-based assays using messenger RNA (mRNA) expression have demonstrated robust diagnostic performance in bladder cancer. The CxBladder Monitor (genes: CDK1, CXCR2, HOXA13, IGFBP5, MDK) reported 91% sensitivity, 96% negative predictive value, and an AUC of 0.73. The Xpert BC test (ABL1, ANXA10, CRH, IGF2, UPK1B) achieved 84% sensitivity and 91% specificity (AUC 0.872). Similarly, UROBEST reached 80% sensitivity and 94% specificity (AUC 0.91), while the Oncocyte 43-gene panel achieved 90% sensitivity and 82.5% specificity (AUC 0.91) [67]. Together, these data highlight that mRNA assays are among the most advanced biomarker tools, with some already available for clinical use.

- miRNAs: MicroRNAs (miRNAs), small regulatory RNAs detectable in urine, have also been explored extensively. A 2022 systematic review of 25 studies (N = 4054) identified multiple miRNA candidates with diagnostic potential, though inter-study variability limited consistent signatures [68]. More recently, a 2024 meta-analysis focusing on miR-143 reported sensitivity 0.80, specificity 0.85, and AUC 0.88, underscoring its potential as a reliable non-invasive marker [69]. It shows promising accuracy but still needs consistent validation.

- lncRNAs: Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), particularly when carried in urinary exosomes, have also been evaluated. A 2021 meta-analysis (1883 bladder cancer patients vs. 1721 controls) demonstrated pooled sensitivity 0.74, specificity 0.76, and AUC 0.83. Importantly, panels of multiple lncRNAs outperformed single markers (AUC 0.86 vs. 0.81), supporting their clinical utility as part of multiparametric approaches [70].

- Emerging Biomarkers and Multi-Omic Signatures: In addition to circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and circulating tumor cells (CTCs), several new biomarkers are under investigation. These include circular RNAs (circRNAs), the RNA demethylase FTO (fat mass and obesity-associated protein, an epitranscriptomic regulator), and distinct protein or peptide signatures—all linked to bladder cancer biology but still requiring further validation [71]. At the genomic level, mutation panels covering genes such as TP53, FGFR3, ERBB2, PIK3CA, ARID1A and FGFR3-ADD1 fusions may help detect minimal residual disease and monitor relapse. These emerging biomarkers could improve early detection and monitoring of bladder cancer once validated.

3.4.4. Integration with Imaging

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| PET | Positron emission tomography |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| AUC | Area under curve |

| BCa | Bladder Cancer |

| BLC | Blue Light Cystoscopy |

| CAD | Computer-Aided Detection |

| CTCs | Circulating Tumor Cells |

| ctDNA | Circulating Tumor DNA |

| CUETO | Club Urológico Español de Tratamiento Oncológico |

| Dx | Diagnosis |

| DFS | Disease-free Survival |

| EORTC | European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer |

| FDG | Fluorodeoxyglucose |

| FAPI | Fibroblast Activation Protein Inhibitor |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| mpMRI | Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging |

| MIBC | Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer |

| NAC | Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy |

| NBI | Narrow Band Imaging |

| NMIBC | Non-Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer |

| OS | Overall Survival |

| PDD | Photodynamic Diagnosis |

| PFS | Progression-Free Survival |

| PSMA | Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen |

| RFS | Recurrence-Free Survival |

| RNA | Ribonucleic Acid |

| SoC | Standard of Care |

| SUVmax | Maximum Standardized Uptake Value |

| T/N/M | Tumor/Node/Metastasis |

| TURBT | Transurethral Resection of Bladder Tumor |

| utDNA | Urinary Tumor DNA |

| WLC | White Light Cystoscopy |

| 18F-FDG: | FDG labeled with fluorine-18 |

| 68Ga-FAPI | Gallium-68-labeled fibroblast activation protein inhibitor |

| 68Ga-FAP-2286 | A specific gallium-68-labeled FAPI radiotracer |

| 68Ga-N188 | Gallium-68-labeled radiotracer targeting Nectin-4 |

| 11C-acetate | Carbon-11-labeled acetate |

| NPV | negative predictive value |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| ADC | antibody–drug conjugate |

| ML | Machine learning |

| TIS | Total immunostaining score |

| Se | Sensitivity |

| Sp | Specificity |

| GU | genitourinary |

| CNN | Convolutional neural network |

| ACS | Attention mechanism based Cystoscopic images Segmentation model |

| FPN | Feature pyramid network |

| HR | Hazard Ratio |

| lncRNA | Long Non-Coding RNA |

| miRNA | MicroRNA |

| mRNA | Messenger RNA |

| MRD | Minimal Residual Disease |

| SERS | Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| BCG | Bacillus Calmette–Guérin |

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Association of Urology. EAU Guidelines: Muscle-Invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer; European Association of Urology: Arnhem, The Netherlands, 2025; Available online: https://uroweb.org/guidelines (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Remmelink, M.J.; Rip, Y.; Nieuwenhuijzen, J.A.; Ket, J.C.; Oddens, J.R.; de Reijke, T.M.; de Bruin, D.M. Advanced optical imaging techniques for bladder cancer detection and diagnosis: A systematic review. BJU Int. 2024, 134, 890–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkolyar, E.; Zhou, S.R.; Carlson, C.J.; Chang, S.; Laurie, M.A.; Xing, L.; Bowden, A.K.; Liao, J.C. Optimizing cystoscopy and TURBT: Enhanced imaging and artificial intelligence. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2024, 22, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, M.; Liu, L.; Du, G.; Fu, Z. Diagnostic Evaluation of 18F-FDG PET/CT Imaging in Recurrent or Residual Urinary Bladder Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Urol. J. 2020, 17, 562–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unterrainer, L.M.; Lindner, S.; Eismann, L.; Casuscelli, J.; Gildehaus, F.-J.; Bui, V.N.; Albert, N.L.; Holzgreve, A.; Beyer, L.; Todica, A.; et al. Feasibility of [68Ga]Ga-FAPI-46 PET/CT for detection of nodal and hematogenous spread in high-grade urothelial carcinoma. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 2022, 49, 3571–3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagens, M.J.; van Leeuwen, P.J.; Wondergem, M.; Boellaard, T.N.; Sanguedolce, F.; Oprea-Lager, D.E.; Bex, A.; Vis, A.N.; van der Poel, H.G.; Mertens, L.S.; et al. A Systematic Review on the Diagnostic Value of Fibroblast Activation Protein Inhibitor PET/CT in Genitourinary Cancers. J. Nucl. Med. 2024, 65, 888–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novruzov, E.; Dendl, K.; Ndlovu, H.; Choyke, P.L.; Dabir, M.; Beu, M.; Novruzov, F.; Mehdi, E.; Guliyev, F.; Koerber, S.A.; et al. Head-to-head Intra-individual Comparison of [68Ga]-FAPI and [18F]-FDG PET/CT in Patients with Bladder Cancer. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2022, 24, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortolan, N.; Urso, L.; Zamberlan, I.; Filippi, L.; Buffi, N.M.; Cittanti, C.; Uccelli, L.; Bartolomei, M.; Evangelista, L. Is There a Role for FAPI PET in Urological Cancers? Mol. Diagn. Ther. 2024, 28, 721–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshkin, V.S.; Kumar, V.; Kline, B.; Escobar, D.; Aslam, M.; Cooperberg, M.R.; Aggarwal, R.R.; de Kouchkovsky, I.; Chou, J.; Meng, M.V.; et al. Initial Experience with 68Ga-FAP-2286 PET Imaging in Patients with Urothelial Cancer. J. Nucl. Med. 2024, 65, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unterrainer, L.M.; Eismann, L.; Lindner, S.; Gildehaus, F.-J.; Toms, J.; Casuscelli, J.; Holzgreve, A.; Kunte, S.C.; Cyran, C.C.; Menold, P.; et al. [68Ga]Ga-FAPI-46 PET/CT for locoregional lymph node staging in urothelial carcinoma of the bladder prior to cystectomy: Initial experiences from a pilot analysis. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 2024, 51, 1786–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, A.; Jambor, I.; Merisaari, H.; Ettala, O.; Virtanen, J.; Koskinen, I.; Veskimae, E.; Sairanen, J.; Taimen, P.; Kemppainen, J.; et al. 11C-acetate PET/MRI in bladder cancer staging and treatment response evaluation to neoadjuvant chemotherapy: A prospective multicenter study (ACEBIB trial). Cancer Imaging 2018, 18, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girard, A.; Dercle, L.; Vila-Reyes, H.; Schwartz, L.H.; Girma, A.; Bertaux, M.; Radulescu, C.; Lebret, T.; Delcroix, O.; Rouanne, M. A machine-learning-based combination of criteria to detect bladder cancer lymph node metastasis on [18F]FDG PET/CT: A pathology-controlled study. Eur. Radiol. 2023, 33, 2821–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Fels, C.A.M.; Leliveld, A.; Buikema, H.; Heuvel, M.C.v.D.; de Jong, I.J. VEGF, EGFR and PSMA as possible imaging targets of lymph node metastases of urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. BMC Urol. 2022, 22, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, X.; Xia, L.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, Y.; Pomper, M.G.; Rowe, S.P.; Li, X.; Li, N.; Zhang, N.; Zhu, H.; et al. First-in-Human Study of the Radioligand 68Ga-N188 Targeting Nectin-4 for PET/CT Imaging of Advanced Urothelial Carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 3395–3407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkolyar, E.; Jia, X.; Chang, T.C.; Trivedi, D.; Mach, K.E.; Meng, M.Q.-H.; Xing, L.; Liao, J.C. Augmented Bladder Tumor Detection Using Deep Learning. Eur. Urol. 2019, 76, 714–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshmand, S.; Bazargani, S.T.; Bivalacqua, T.J.; Holzbeierlein, J.M.; Willard, B.; Taylor, J.M.; Liao, J.C.; Pohar, K.; Tierney, J.; Konety, B. Blue light cystoscopy for the diagnosis of bladder cancer: Results from the US prospective multicenter registry. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2018, 36, 361.e1–361.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, G.I.; Sholklapper, T.N.; Cocci, A.; Broggi, G.; Caltabiano, R.; Smith, A.B.; Lotan, Y.; Morgia, G.; Kamat, A.M.; Witjes, J.A.; et al. Performance of Narrow Band Imaging (NBI) and Photodynamic Diagnosis (PDD) Fluorescence Imaging Compared to White Light Cystoscopy (WLC) in Detecting Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer: A Systematic Review and Lesion-Level Diagnostic Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2021, 13, 4378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Muvhar, R.; Paluch, R.; Mekayten, M. Recent Advances and Emerging Innovations in Transurethral Resection of Bladder Tumor (TURBT) for Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer: A Comprehensive Review of Current Literature. Res. Rep. Urol. 2025, 17, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Shi, H.; Luo, J.; Guo, X.; Wang, B.; Liu, Y.; Yu, J. Diagnostic and therapeutic effects of fluorescence cystoscopy and narrow-band imaging in bladder cancer: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Int. J. Surg. 2023, 109, 3169–3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Gu, Z.; Chen, F.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, G. Application of artificial intelligence in the diagnosis and treatment of urinary tumors. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1440626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.; Bolenz, C.; Todenhöfer, T.; Stenzel, A.; Deetmar, P.; Knoll, T.; Porubsky, S.; Hartmann, A.; Popp, J.; Kriegmair, M.C.; et al. Deep learning-based classification of blue light cystoscopy imaging during transurethral resection of bladder tumors. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlobina, N.V.; Budylin, G.S.; Tseregorodtseva, P.S.; Andreeva, V.A.; Sorokin, N.I.; Kamalov, D.M.; Strigunov, A.A.; Armaganov, A.G.; Kamalov, A.A.; Shirshin, E.A. In vivo assessment of bladder cancer with diffuse reflectance and fluorescence spectroscopy: A comparative study. Lasers Surg. Med. 2024, 56, 496–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutaguchi, J.; Morooka, K.; Kobayashi, S.; Umehara, A.; Miyauchi, S.; Kinoshita, F.; Inokuchi, J.; Oda, Y.; Kurazume, R.; Eto, M. Artificial Intelligence for Segmentation of Bladder Tumor Cystoscopic Images Performed by U-Net with Dilated Convolution. J. Endourol. 2022, 36, 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, A.; Nosato, H.; Kochi, Y.; Kojima, T.; Kawai, K.; Sakanashi, H.; Murakawa, M.; Nishiyama, H. Support System of Cystoscopic Diagnosis for Bladder Cancer Based on Artificial Intelligence. J. Endourol. 2020, 34, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Z.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; He, C.; He, G.; Ji, Z. Leveraging Deep Learning in Real-Time Intelligent Bladder Tumor Detection During Cystoscopy: A Diagnostic Study. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2025, 32, 3220–3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Chen, X.; Pan, J.; Dong, W.; Diao, X.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qian, G.; Chen, H.; et al. An Artificial Intelligence System for the Detection of Bladder Cancer via Cystoscopy: A Multicenter Diagnostic Study. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2021, 114, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Ham, W.S.; Koo, K.C.; Lee, J.; Ahn, H.K.; Jeong, J.Y.; Baek, S.Y.; Lee, S.J.; Lee, K.S. Evaluation of the Diagnostic Efficacy of the AI-Based Software INF-M01 in Detecting Suspicious Areas of Bladder Cancer Using Cystoscopy Images. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Jiang, L.; Yang, K.; Luo, B.; Wang, X. A novel artificial intelligence segmentation model for early diagnosis of bladder tumors. Abdom. Imaging 2024, 50, 3092–3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tao, Z.; Li, R.; Bi, H. A comparative study of attention mechanism based deep learning methods for bladder tumor segmentation. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2023, 171, 104984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lai, L.; Li, Y.; Zhou, X.; Cheng, X.; Chen, Y.; Huang, H.; Guo, J.; Wang, G. A lightweight bladder tumor segmentation method based on attention mechanism. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2024, 62, 1519–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, W.K.; Jo, S.B.; Han, D.E.; Ahn, S.T.; Oh, M.M.; Park, H.S.; Moon, D.G.; Choi, I.; Yang, Z.; Kim, J.W. Artificial Intelligence-Based Classification and Segmentation of Bladder Cancer in Cystoscope Images. Cancers 2024, 17, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baana, M.; Arkwazi, M.; Zhao, Y.; Ofagbor, O.; Bhardwaj, G.; Lami, M.; Bolton, E.; Heer, R. Using artificial intelligence for bladder cancer detection during cystoscopy and its impact on clinical outcomes: A protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e089125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, J.W.; Koo, K.C.; Chung, B.H.; Baek, S.Y.; Lee, S.J.; Park, K.H.; Lee, K.S. Deep learning diagnostics for bladder tumor identification and grade prediction using RGB method. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.Y.; Lee, Y.S.; Tae, J.H.; Chang, I.H.; Kim, T.-H.; Myung, S.C.; Nguyen, T.T.; Lee, J.H.; Choi, J.; Kim, J.H.; et al. Selection of Convolutional Neural Network Model for Bladder Tumor Classification of Cystoscopy Images and Comparison with Humans. J. Endourol. 2024, 38, 1036–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Shkolyar, E.; Laurie, M.A.; Eminaga, O.; Liao, J.C.; Xing, L. Tumor detection under cystoscopy with transformer-augmented deep learning algorithm. Phys. Med. Biol. 2023, 68, 165013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.C.; Shkolyar, E.; Del Giudice, F.; Eminaga, O.; Lee, T.; Laurie, M.; Seufert, C.; Jia, X.; Mach, K.E.; Xing, L.; et al. Real-time Detection of Bladder Cancer Using Augmented Cystoscopy with Deep Learning: A Pilot Study. J. Endourol. 2023, 37, 747–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negassi, M.; Suarez-Ibarrola, R.; Hein, S.; Miernik, A.; Reiterer, A. Application of artificial neural networks for automated analysis of cystoscopic images: A review of the current status and future prospects. World J. Urol. 2020, 38, 2349–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitiello, A.; Ferrara, F.; Lasala, R.; Zovi, A. Precision Medicine in the Treatment of Locally Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Cancer: New Molecular Targets and Pharmacological Therapies. Cancers 2022, 14, 5167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardana, R.; Mishra, S.K.; Williamson, S.R.; Mohanty, A.; Mohanty, S.K. Immune checkpoints and their inhibitors: Reappraisal of a novel diagnostic and therapeutic dimension in the urologic malignancies. Semin. Oncol. 2020, 47, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednova, O.; Leyton, J.V. Targeted Molecular Therapeutics for Bladder Cancer—A New Option beyond the Mixed Fortunes of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; He, M.; Li, J.; Li, L. Immunotherapeutic strategies for invasive bladder cancer: A comprehensive review. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1591379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaud, É.; Mansure, J.J.; Kassouf, W. Integrating novel immunotherapeutic approaches in organ-preserving therapies for bladder cancer. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2024; early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dercle, L.; Sun, S.; Seban, R.-D.; Mekki, A.; Sun, R.; Tselikas, L.; Hans, S.; Bernard-Tessier, A.; Bouvier, F.M.; Aide, N.; et al. Emerging and Evolving Concepts in Cancer Immunotherapy Imaging. Radiology 2023, 306, e239003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.J.; Subesinghe, M.; Taylor, B.; Bille, A.; Spicer, J.; Papa, S.; Goh, V.; Cook, G.J.R. 18F FDG PET/CT and Novel Molecular Imaging for Directing Immunotherapy in Cancer. Radiology 2022, 304, 246–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Necchi, A.; Roumiguié, M.; Kamat, A.M.; Shore, N.D.; Boormans, J.L.; Esen, A.A.; Lebret, T.; Kandori, S.; Bajorin, D.F.; Krieger, L.E.M.; et al. Pembrolizumab monotherapy for high-risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer without carcinoma in situ and unresponsive to BCG (KEYNOTE-057): A single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2024, 25, 720–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Huang, Y.; Li, C.; Liang, Y.; Huang, M.; Luo, R.; Liang, W. Efficacy and safety of neoadjuvant PD-1 inhibitors or PD-L1 inhibitors for muscle invasive bladder cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 14, 1332213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckabir, W.; Zhou, M.; Lee, J.S.; Vensko, S.P.; Woodcock, M.G.; Wang, H.-H.; Wobker, S.E.; Atassi, G.; Wilkinson, A.D.; Fowler, K.; et al. Immune features are associated with response to neoadjuvant chemo-immunotherapy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germanà, E.; Pepe, L.; Pizzimenti, C.; Ballato, M.; Pierconti, F.; Tuccari, G.; Ieni, A.; Giuffrè, G.; Fadda, G.; Fiorentino, V.; et al. Programmed Cell Death Ligand 1 (PD-L1) Immunohistochemical Expression in Advanced Urothelial Bladder Carcinoma: An Updated Review with Clinical and Pathological Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roviello, G.; Catalano, M.; Nobili, S.; Santi, R.; Mini, E.; Nesi, G. Focus on Biochemical and Clinical Predictors of Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma: Where Do We Stand? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, D.; Bonacorsi, S.; Smith, R.A.; Weber, W.; Hayes, W. Molecular Imaging and the PD-L1 Pathway: From Bench to Clinic. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 698425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abenavoli, E.M.; Linguanti, F.; Calabretta, R.; Bolton, R.C.D.; Berti, V.; Lopci, E. Clinical Application of ImmunoPET Targeting Checkpoint Inhibitors. Cancers 2023, 15, 5675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshkin, V.S.; Henderson, N.; James, M.; Natesan, D.; Freeman, D.; Nizam, A.; Su, C.T.; Khaki, A.R.; Osterman, C.K.; Glover, M.J.; et al. Efficacy of enfortumab vedotin in advanced urothelial cancer: Analysis from the Urothelial Cancer Network to Investigate Therapeutic Experiences (UNITE) study. Cancer 2021, 128, 1194–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, J.; Trepka, K.; Sjöström, M.; Egusa, E.A.; Chu, C.E.; Zhu, J.; Chan, E.; Gibb, E.A.; Badura, M.L.; Contreras-Sanz, A.; et al. TROP2 Expression Across Molecular Subtypes of Urothelial Carcinoma and Enfortumab Vedotin-resistant Cells. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2022, 5, 714–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loriot, Y.; Petrylak, D.; Kalebasty, A.R.; Fléchon, A.; Jain, R.; Gupta, S.; Bupathi, M.; Beuzeboc, P.; Palmbos, P.; Balar, A.; et al. TROPHY-U-01, a phase II open-label study of sacituzumab govitecan in patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma progressing after platinum-based chemotherapy and checkpoint inhibitors: Updated safety and efficacy outcomes. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martini, D.J.; Case, K.B.; Gratz, D.; Pellegrini, K.; Beagle, E.; Schneider, T.; Dababneh, M.; Nazha, B.; Brown, J.T.; Joshi, S.S.; et al. PD-L1 and nectin-4 expression and genomic characterization of bladder cancer with divergent differentiation. Cancer 2024, 130, 3658–3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, X.; Wang, D.; Zhang, X.; Xu, M.; Huang, Y.; Qin, W.; Chen, S. Unleashing the power of urine-based biomarkers in diagnosis, prognosis and monitoring of bladder cancer (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 2025, 66, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.J.; Kakehi, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Wu, X.X.; Yuasa, T.; Yoshiki, T.; Okada, Y.; Terachi, T.; Ogawa, O. Detection of circulating cancer cells by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction for uroplakin II in peripheral blood of patients with urothelial cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000, 6, 3166–3171. [Google Scholar]

- Lodewijk, I.; Dueñas, M.; Rubio, C.; Munera-Maravilla, E.; Segovia, C.; Bernardini, A.; Teijeira, A.; Paramio, J.M.; Suárez-Cabrera, C. Liquid Biopsy Biomarkers in Bladder Cancer: A Current Need for Patient Diagnosis and Monitoring. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Fan, W.; Deng, Q.; Tang, S.; Wang, P.; Xu, P.; Wang, J.; Yu, M. The prognostic and diagnostic value of circulating tumor cells in bladder cancer and upper tract urothelial carcinoma: A meta-analysis of 30 published studies. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 59527–59538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liliana, B.; Zulfiqqar, A.; Mataho, N.L.; Subekti, E. The Use of Circulating Tumor Cells in T1 Stage Non-muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Urol. Res. Pract. 2025, 50, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ma, C.; Li, X.; Li, A.; Wang, Z. Circulating tumor cells correlating with Ki-67 predicts the prognosis of bladder cancer patients. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2022, 55, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beije, N.; de Kruijff, I.; de Jong, J.; Klaver, S.; de Vries, P.; Jacobs, R.; Somford, D.; Slaa, E.T.; van der Heijden, A.; Witjes, J.A.; et al. Circulating tumour cells to drive the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer. ESMO Open 2022, 7, 100416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, J.C.M.; Massie, C.; Garcia-Corbacho, J.; Mouliere, F.; Brenton, J.D.; Caldas, C.; Pacey, S.; Baird, R.; Rosenfeld, N. Liquid biopsies come of age: Towards implementation of circulating tumour DNA. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosso, A.; Cadenar, A.; Pillozzi, S.; Carli, G.; Lipparini, F.; Di Maida, F.; Pichler, R.; Krajewski, W.; Albisinni, S.; Laukhtina, E.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA in muscle-invasive bladder cancer: A systematic review. Actas Urol. Esp. 2025, 49, 501717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, J.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ni, Y.; Xu, N.; Zhao, F.; Tang, Y.; Liu, H.; Sun, G.; et al. Prognostic significance of circulating tumor DNA in urothelial carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Surg. 2024, 110, 3923–3936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavalieris, L.; O’sUllivan, P.; Frampton, C.; Guilford, P.; Darling, D.; Jacobson, E.; Suttie, J.; Raman, J.D.; Shariat, S.F.; Lotan, Y. Performance Characteristics of a Multigene Urine Biomarker Test for Monitoring for Recurrent Urothelial Carcinoma in a Multicenter Study. J. Urol. 2017, 197, 1419–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimaldi, A.M.; Lapucci, C.; Salvatore, M.; Incoronato, M.; Ferrari, M. Urinary miRNAs as a Diagnostic Tool for Bladder Cancer: A Systematic Review. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Sen, Y.; Ye, J. miRNA-143 as a potential biomarker in the detection of bladder cancer: A meta-analysis. Futur. Oncol. 2024, 20, 1275–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Wu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, C.; Zhang, L.; Zuo, L. Exosome-Derived Long Non-Coding RNAs as Non-Invasive Biomarkers of Bladder Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 719863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Zou, L.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, P.; Li, C.; Li, Z.; Niu, H.; Zhang, X.; Liao, H.; Cheng, L.; et al. Prognostic role of circRNAs and RNA methylation enzymes in bladder cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of Chinese studies. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2025, 43, 628–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandekerkhove, G.; Todenhöfer, T.; Annala, M.; Struss, W.J.; Wong, A.; Beja, K.; Ritch, E.; Brahmbhatt, S.; Volik, S.V.; Hennenlotter, J.; et al. Circulating Tumor DNA Reveals Clinically Actionable Somatic Genome of Metastatic Bladder Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 6487–6497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Bhandary, P.; Griffin, K.; Moore, J.H.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.P. Integrative multi-omics study identifies sex-specific molecular signatures and immune modulation in bladder cancer. Front. Bioinform. 2025, 5, 1575790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moisoiu, T.; Dragomir, M.P.; Iancu, S.D.; Schallenberg, S.; Birolo, G.; Ferrero, G.; Burghelea, D.; Stefancu, A.; Cozan, R.G.; Licarete, E.; et al. Combined miRNA and SERS urine liquid biopsy for the point-of-care diagnosis and molecular stratification of bladder cancer. Mol. Med. 2022, 28, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Pagano, I.; Sun, Y.; Murakami, K.; Goodison, S.; Vairavan, R.; Tahsin, M.; Black, P.C.; Rosser, C.J.; Furuya, H. A Diagnostic Gene Expression Signature for Bladder Cancer Can Stratify Cases into Prescribed Molecular Subtypes and Predict Outcome. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavan, N.; Scaggiante, B. Editorial: Liquid biopsy in the detection and prediction of outcomes in bladder cancer. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1391466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindskrog, S.V.; Strandgaard, T.; Nordentoft, I.; Galsky, M.D.; Powles, T.; Agerbæk, M.; Jensen, J.B.; Alix-Panabières, C.; Dyrskjøt, L. Circulating tumour DNA and circulating tumour cells in bladder cancer—From discovery to clinical implementation. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2025, 22, 590–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, N.J.; Temperley, H.C.; Corr, A.; Meaney, J.F.; Lonergan, P.E.; Kelly, M.E. Current role of radiomics and radiogenomics in predicting oncological outcomes in bladder cancer. Curr. Urol. 2024, 19, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shohdy, K.S.; Villamar, D.M.; Cao, Y.; Trieu, J.; Price, K.S.; Nagy, R.; Tagawa, S.T.; Molina, A.M.; Sternberg, C.N.; Nanus, D.M.; et al. Serial ctDNA analysis predicts clinical progression in patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 2022, 126, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Chen, F.; Lopez-Beltran, A.; Necchi, A.; Cimadamore, A.; Spiess, P.E.; Li, R.; Roy-Chowdhuri, S.; Montironi, R.; Golijanin, D.; et al. Urinary Tumor DNA–based Liquid Biopsy in Bladder Cancer Management: A Systematic Review. Eur. Urol. Focus 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuszczak, M.; Salagierski, M. Diagnostic and Prognostic Potential of Biomarkers CYFRA 21.1, ERCC1, p53, FGFR3 and TATI in Bladder Cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wu, H.; Jiang, J.; Bao, S.; Ling, C. The value of circulating tumor DNA in the prognostic diagnosis of bladder cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Urol. Int. 2025, 109, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Wang, J.; Yu, Z.; Lu, J.; Sun, Z.; Chen, Z. Redefining bladder cancer treatment: Innovations in overcoming drug resistance and immune evasion. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1537808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahangar, M.; Mahjoubi, F.; Mowla, S.J. Bladder cancer biomarkers: Current approaches and future directions. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1453278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, E.; Birkenkamp-Demtröder, K.; Sethi, H.; Shchegrova, S.; Salari, R.; Nordentoft, I.; Wu, H.-T.; Knudsen, M.; Lamy, P.; Lindskrog, S.V.; et al. Early Detection of Metastatic Relapse and Monitoring of Therapeutic Efficacy by Ultra-Deep Sequencing of Plasma Cell-Free DNA in Patients with Urothelial Bladder Carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 1547–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brembilla, G.; Basile, G.; Cosenza, M.; Giganti, F.; Del Prete, A.; Russo, T.; Pennella, R.; Lavalle, S.; Raggi, D.; Mercinelli, C.; et al. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy VI-RADS Scores for Assessing Muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer Response to Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy with Multiparametric MRI. Radiology 2024, 313, e233020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouba, E.; Lopez-Beltran, A.; Montironi, R.; Massari, F.; Huang, K.; Santoni, M.; Chovanec, M.; Cheng, M.; Scarpelli, M.; Zhang, J.; et al. Liquid biopsy in the clinical management of bladder cancer: Current status and future developments. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2019, 20, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koguchi, D.; Matsumoto, K.; Shiba, I.; Harano, T.; Okuda, S.; Mori, K.; Hirano, S.; Kitajima, K.; Ikeda, M.; Iwamura, M. Diagnostic Potential of Circulating Tumor Cells, Urinary MicroRNA, and Urinary Cell-Free DNA for Bladder Cancer: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Clinical Question | Do Novel Molecular Imaging, AI-Assisted Cystoscopy, Theragnostics, and Molecular Biomarkers Improve Detection/Staging/Management vs. SoC in Patients with Bladder Cancer? |

|---|---|

| Population | (1) Humans; (2) Adults; (3) Patients with localized and/or advanced bladder cancer |

| Intervention | New PET tracers, PET/CT–PET/MRI, radiomics; AI-cystoscopy, NBI; theragnostics; ctDNA/utDNA, CTCs, multi-omics. |

| Comparison | Conventional imaging (CT, MRI, or [18F]FDG PET/CT); expert interpretation alone (for AI studies); standard clinical staging protocols. SoC: WLC ± BLC/NBI (no AI); urine cytology; EORTC/CUETO scores. |

| Outcomes | Primary: Sensitivity/specificity/AUC, T/N/M accuracy, change-in-management, minimal residual disease (ctDNA/utDNA), RFS/PFS/OS, therapy selection. Secondary: workflow, inter-reader, safety, cost-effectiveness, feasibility. |

| Study types | Prospective or retrospective clinical studies, systematic reviews, pilot feasibility studies |

| Databases searched | PubMed, Embase, Cochrane |

| Search keywords | Bladder cancer AND (PET/PET-CT/PET-MRI/FAPI/PSMA/radiomics) OR (cystoscopy AND AI/CAD/BLC/PDD/NBI) OR (theragnostic/radioligand) OR (biomarker/ctDNA/utDNA/CTC). |

| Manual search | Screening reference lists and journal issues by hand |

| Inclusion criteria | Adult BCa (NMIBC/MIBC) Diagnostic/staging & treatment response studies (2015–2025) Novel PET tracers vs. FDG/conventional imaging AI applied to PET/CT, MRI, cystoscopy/optical imaging Quantitative metrics (sens., spec., AUC, SUVmax) Biomarkers (ctDNA, CTCs, RNA, proteins) for Dx/prognosis/follow-up Imaging–biomarker integration (radiomics, mpMRI, multimodal) English/Spanish publications |

| Exclusion criteria | Reviews without patient-level data; case reports, editorials, abstracts without full text, opinion pieces |

| Authors | Year | Study Type | Main Objective | n | Additional Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unterrainer et al. [6] | 2022 | Prospective | Detect nodal/hematogenous spread with 68Ga-FAPI-46 PET/CT | 15 | Improved detection over CT; useful for early metastatic staging |

| Novruzov et al. [8] | 2022 | Intra-individual comparison | Compare 68Ga-FAPI vs. 18F-FDG PET/CT in bladder cancer | 8 | Superior sensitivity in small nodes/peritoneum |

| Koshkin et al. [10] | 2024 | Prospective (NCT04621435) | Evaluate 68Ga-FAP-2286 PET/CT in urothelial carcinoma | 21 | Altered clinical decisions in 3 patients |

| Ortolan et al. [9] | 2024 | Narrative review | Discuss role of FAPI PET in urological cancers | – | Emphasizes diagnostic and theragnostic potential |

| Unterrainer et al. [11] | 2024 | Prospective | Assess locoregional LN staging with 68Ga-FAPI-46 PET/CT | 18 | Useful for surgical planning |

| Hagens et al. [7] | 2024 | Systematic review | Review diagnostic value of FAPI PET/CT in GU cancers | 10 | Encourages protocol optimization |

| Salminen et al. [12] | 2018 | Multicenter prospective (NCT01918592) | Evaluate 11C-acetate PET/MRI for staging and NAC response | 22 | Useful for monitoring response, not nodal staging |

| Girard et al. [13] | 2023 | Retrospective + ML | Machine learning model for LN metastasis detection on FDG PET/CT | 87 | Objective, reproducible tool |

| van der Fels et al. [14] | 2022 | Immunohistochemical study | Assess VEGF, EGFR, PSMA in nodal mets of bladder cancer | 48 (LNs) | Only VEGF viable for imaging |

| Duan et al. [15] | 2023 | First-in-human (NCT05321316) | Evaluate 68Ga-N188 PET for Nectin-4 imaging | 32 | Promising diagnostic companion for ADCs |

| Authors | Year | Study Type | n | Main Objective | AI/System | Arquitecture/Model | Image Technique |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ye et al. [26] | 2025 | Prospective diagnostic accuracy study | 94 | Evaluate AI (HRNetV2) for real-time bladder lesion detection during cystoscopy. | HRNetV2 | CNN | WLC |

| Shkolyar et al. [4] | 2025 | Review study | - | Review enhanced imaging and AI use in cystoscopy and TURBT. | CystoNet-T | CNN | WLC |

| Li et al. [29] | 2025 | Retrospective diagnostic study | 273 | Develop an AI model (BTS-Net) for bladder tumor segmentation in imaging. | BTS-Net | Segmentation net | WLC |

| Kim et al. [28] | 2024 | Randomized retrospective clinical trial | 5670 | Validate AI software INF-M01 for detecting bladder tumors in cystoscopy images | INF-M01 | CNN | WLC |

| Zhu et al. [21] | 2024 | Narrative review | - | Review machine learning/deep learning applications in urological cancer diagnosis and treatment. | Machine learning and deep learning | CNN | CT, MRI, US and cystoscopy images |

| Zlobina et al. [23] | 2024 | Observational comparative study | 21 | Assess spectroscopy for in vivo bladder cancer detection. | Machine learning | Classification algorithms | Fluorescence and diffuse reflectance spectroscopy |

| Hwang et al. [32] | 2024 | Single-center diagnostic classification and segmentation study. | 772 | Use VGG19 to classify bladder lesions and Deeplab v3+ to segment morphological types in cystoscopy images. | VGG19 + BeepLab v3+ | CNN + segmentation net | WLC |

| Lee et al. [35] | 2024 | Prospective comparative diagnostic study | 543 | Identify the best CNN model (EfficientNetB0) for classifying bladder tumors in cystoscopy images. | EfficientNetB0 | CNN | WLC |

| Zhao el al. [31] | 2024 | Diagnostic image-based segmentation study. | - | Propose NAFF-Net efficient segmentation of bladder tumors in endoscopic images | NAFF-Net | Segmentation net | WLC |

| Jia X et al. [36] | 2023 | Prospective pilot diagnostic study | 67 | Develop and test CystoNet-T for bladder tumor detection in WLC. | CystoNet-T | FPN | WLC |

| Chang et al. [37] | 2023 | Prospective pilot diagnostic study | 50 | Evaluate real-time CystoNet AI system integrated into live cystoscopy/TURBT video to detect bladder tumors during procedures. | CystoNet | CNN | WLC |

| Zhang et al. [30] | 2023 | Retrospective comparative study | - | Compare various attention mechanisms to improve bladder tumor segmentation performance in cystoscopic images. | Deep learning | ACS | WLC |

| Mutaguchi et al. [24] | 2022 | Retrospective diagnostic segmentation study. | 120 | Compare Dilated U-Net vs. standard U-Net for accurate bladder tumor segmentation in cystoscopy images. | U-net | Dilated convolution | WLC |

| Wu et al. [27] | 2022 | Multicenter prospective diagnostic study. | 10,729 | Evaluate CAIDS for detecting bladder cancer via cystoscopy, comparing its diagnostic accuracy against standard clinical assessment | CAIDS algorithm | Pyramid Scene Parsing Network (PSPNet) | WLC |

| Yoo et al. [34] | 2022 | Retrospective diagnostic study | 10,991 | Evaluate Mask R-CNN for tumor detection and grade prediction from WLC and narrow-band images. | Deep learning | Mask R-CNN | WLC + NBI |

| Ali et al. [22] | 2021 | Multicenter retrospective diagnostic classification study | 216 | Train and evaluate CNNs to classify malignancy, invasiveness, and grade from BLC. | Deep learning | CNN | BLC |

| Ikeda et al. [25] | 2020 | Retrospective diagnostic study. | 109 | Train a GoogLeNet-based CNN to distinguish tumor vs. normal bladder images | Deep learning | CNN | WLC |

| Shkolyar et al. [16] | 2019 | Multicenter prospective diagnostic study | 95 | Develop and validate CystoNet for automated bladder tumor detection in WLC. | CystoNet | CNN | WLC |

| Authors | Year | Study Type | Main Objective | n | Key Statistical Findings | Additional Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lodewijk et al. [59] | 2018 | Narrative review | Types, potential and applications of biomarkers in BCa. | - | Detect a much lower tumor burden | Generate significant anxiety and lead to patient overtreatment. |

| Zhang et al. [60] | 2017 | Meta-Analysis | The prognostic and diagnostic value of CTCs in BCa. | 30 | CTCs are an independent predictive indicator of poor outcomes. | - |

| Wan et al. [57] | 2025 | Review | Relevance of urine biomarkers | - | Advancements and limitations in BCa biomarkers | - |

| Lindskrog et al. [77] | 2025 | Review | Potential of ctDNA and CTC as biomarkers | - | Several studies have shown clinical potential | Combining biomarkers enhances diagnostic results. |

| Zulfiqqar et al. [61] | 2025 | Systematic Review and Meta Analysis | CTC positivity and recurrence and progression to NMIBC | 5 | CTCs enhance prognostic accuracy and therapeutic strategies in NMIBC, | CTC positivity after TURBT predicted recurrence |

| Liu et al. [62] | 2022 | Prospective | The value of CTCs and Ki-67 in prognosis | 84 | Ki-67 high expression associates with high postoperative CTC counts | - |

| Beije et al. [63] | 2022 | Multicenter Prospective Study | CTCs to drive the use of NAC in MIBC | 273 | CTC+ who received NAC survived longer | Negative CTCs alone does not justify withholding NAC. |

| Grosso et al. [65] | 2025 | Systematic Review | Prognostic role of ctDNA in the perioperative of MIBC | 8 | ctDNA+ pre and postoperative associates with poor clinical outcomes. | ctDNA could guide NAC management. |

| Liu et al. [66] | 2024 | Meta Analysis | Prognostic significance of ctDNA in BCa | 1275 | Strong association of ctDNA dynamic change with survival outcomes. | Clinical utility of ctDNA in prognosis |

| Li et al. [69] | 2024 | Study | Value of miRNA-143 in the early detection of BCa | 4054 | Sensitivity and specificity were 0.80 and 0.85 | Coupled with miR-100, it showed better diagnostic power |

| Vandekerkhove et al. [72] | 2017 | Study | ctDNA to profile the tumor genome in real-time in BCa | 51 | ctDNA provides a practical and cost-effective snapshot of driver gene status in metastatic BCa | 95% of metastatic patients harboring alterations to TP53, RB1, or MDM2, an 70% in ARID1 |

| Moisoiu et al. [74] | 2022 | Retrospective cohort | Combined miRNA and SERS for diagnosis and molecular stratification | 31 | miRNA profiling synergizes with SERS | Discriminate between high-grade and low-grade tumors and between luminal and basal types. |

| O’Sullivan et al. [78] | 2025 | Review | Radiomics-based nomogram to predict oncological outcomes in BCa | Several studies demonstrate the predictive potential of radiogenomic | Further studies are required to validate the results | |

| Shohdy et al. [79] | 2022 | Prospective study | ctDNA as a dynamic tool for changes in the VAF of genomic alterations | 53 | Serial ctDNA analysis predicts disease radiologic progression | - |

| Lee et al. [80] | 2025 | Review | The current state of utDNA as a marker of BCa | - | utDNAl improves on most of stages of detection, treatment, and monitoring | - |

| Matuszcz et al. [81] | 2020 | Review | Find the one urine biomarker with the best specificity and sensitivity | p53, FGFR3, CYFRA 21-1, and ERCC1 clinical applications | - | |

| Yu Lu et al. [82] | 2025 | Meta-Analysis | Predictive value of ctDNA detection for disease progression and metastasis risk | 9 | ctDNA demonstrates some application value in the prognostic, recurrence and survival. | Not enough to replace traditional assessment methods |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Albers Acosta, E.; Pelari Mici, L.; Güemez, C.M.; Velasco Balanza, C.; Saavedra Centeno, M.; Pérez Pérez, M.; Celada Luis, G.; Quicios Dorado, C.; Subiela, J.D.; España Navarro, R.; et al. Beyond Visualization: Advanced Imaging, Theragnostics and Biomarker Integration in Urothelial Bladder Cancer. Cancers 2025, 17, 3261. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193261

Albers Acosta E, Pelari Mici L, Güemez CM, Velasco Balanza C, Saavedra Centeno M, Pérez Pérez M, Celada Luis G, Quicios Dorado C, Subiela JD, España Navarro R, et al. Beyond Visualization: Advanced Imaging, Theragnostics and Biomarker Integration in Urothelial Bladder Cancer. Cancers. 2025; 17(19):3261. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193261

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlbers Acosta, Eduardo, Lira Pelari Mici, Carlos Márquez Güemez, Clara Velasco Balanza, Manuel Saavedra Centeno, Marta Pérez Pérez, Guillermo Celada Luis, Cristina Quicios Dorado, José Daniel Subiela, Rodrigo España Navarro, and et al. 2025. "Beyond Visualization: Advanced Imaging, Theragnostics and Biomarker Integration in Urothelial Bladder Cancer" Cancers 17, no. 19: 3261. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193261

APA StyleAlbers Acosta, E., Pelari Mici, L., Güemez, C. M., Velasco Balanza, C., Saavedra Centeno, M., Pérez Pérez, M., Celada Luis, G., Quicios Dorado, C., Subiela, J. D., España Navarro, R., Toquero Diez, P., Laorden, N. R., & Manso, L. S. J. (2025). Beyond Visualization: Advanced Imaging, Theragnostics and Biomarker Integration in Urothelial Bladder Cancer. Cancers, 17(19), 3261. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193261