“Are You Just Looking to ‘Survive’?”: A Qualitative Study of Importance of Oncology Endpoints Beyond Overall Survival in Early-Stage Cancer †

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sample Size and Recruitment Criteria

2.3. Participant Recruitment

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Analyses

2.6. Reflexivity and Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

3.2. Participant Perspectives on OS as a Trial Endpoint

“It helps you plan for the rest of your life. If somebody says to you, ‘You have one year to be alive’ or ‘You have 10 years to be alive’ I think you would behave differently. You would pack these 10 years in one year…[OS] has some importance for the quality of life and what you want to achieve in your life”—ID11

“It’s a funny word, ‘survival,’ because that … captures the essence of everything you’re asking, really. Are you just looking to ‘survive’? Are you looking to really lead a completely normal and healthy life going forward, and where is the gap between those two things?”—ID26

3.3. Participant Perspectives on Non-OS Endpoints

“I can’t imagine them waiting for overall survival to put something on the market. Then I find it amazing how many people are saying ‘‘Well, the drug is available in the States, but it’s not available here yet,’ or…It’s not covered by our insurance yet, but it’s covered by so-and-so’s insurance.’… I don’t think they can wait for [OS]. They just have to do it. You have to save as many of us as possible.”–ID22

3.4. Valuing Specific Non-OS Endpoints Differently

“[Being] recurrence-free would be more aligned with what I would want, because obviously the goal would be not to have to go through chemo, radiation, [and] surgeries again. So, of course, overall survival is important, but if I’m living but I’m living with other cancer and going through treatment, that wouldn’t be the goal.”—ID05

3.5. Other Factors Influencing Perspectives of Importance of Endpoints

“I was hoping to be cured, of course. That was my main goal. If not, something that would extend my life for another few years. The other one, of course, was to be able to continue on with my life and return to work and spend time with my family.”—ID14

“After my surgery, when the clinical trial was offered, I was told that the immunotherapy drug had not been tried on my type of cancer. So, I was the first one to get it. Throwing something at the wall and seeing if it would stick. But it was all that was being offered … so I jumped at it.”—ID36

3.6. Patient Agency and Decision-Making at an Individual and Population Level

“It’s really encouraging to know that alternative endpoints are being considered that can provide patients with greater options for therapy … Whether it’s a complete response or a cure or just maintaining quality of life, all of those things are important. … My guess is that in talking to cancer patients, you will be hearing a lot of the same feedback, that people are willing to take those risks because the alternative is worse, and that if people are willing to try that with the guidance of their medical teams, those options should be available.”—ID02

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COREQ | COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research |

| DCE | Discrete choice experiment |

| DFS | Disease-free survival |

| EFS | Event-free survival |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| HRQoL | Health-related quality of life |

| HTA | Health technology assessment |

| OS | Overall survival |

| pCR | Pathological complete response |

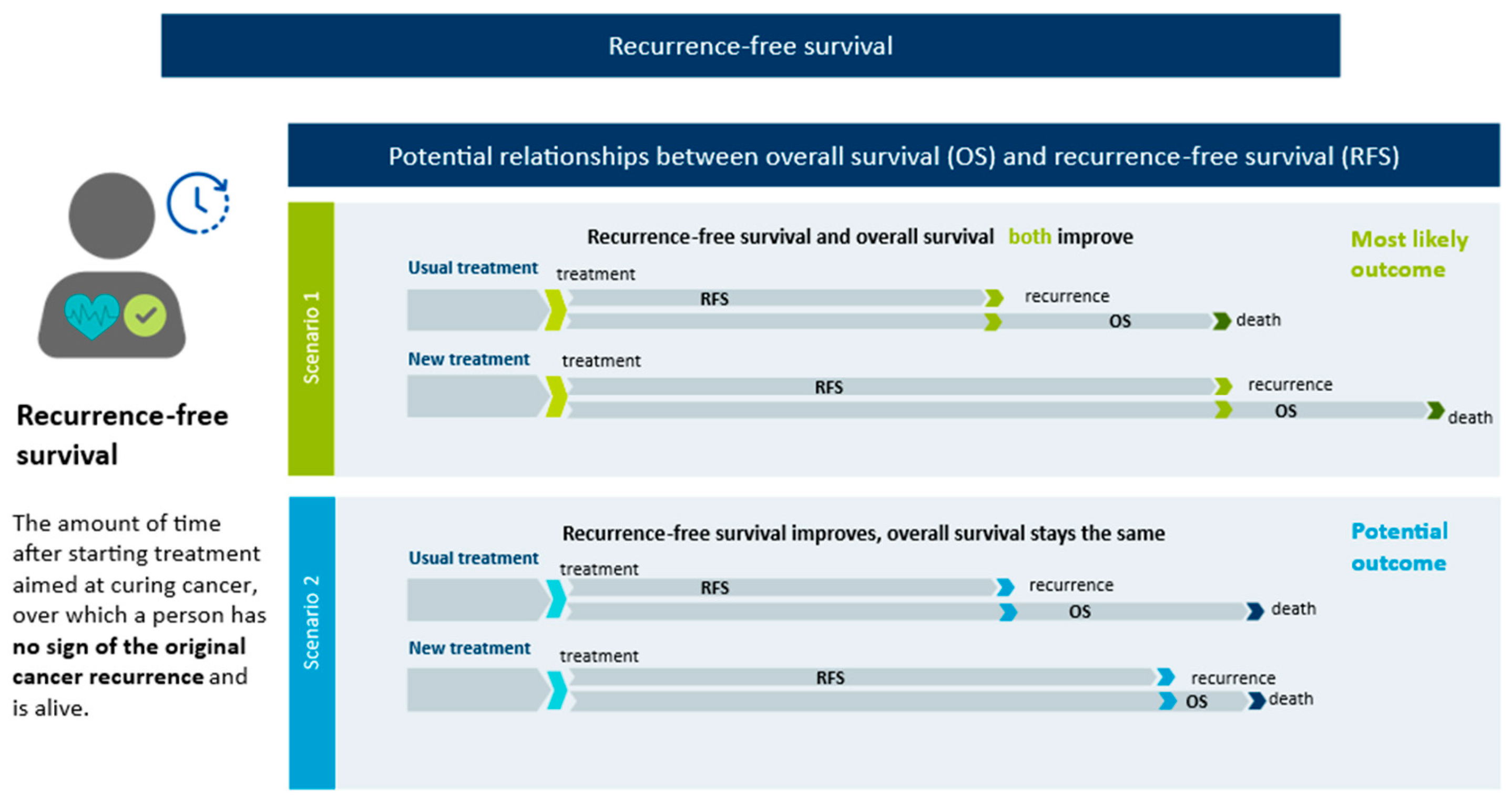

| RFS | Recurrence-free survival |

| SD | Standard deviation |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Non-OS Endpoint Definitions

- Pathologic complete response (pCR), defined as “the absence of residual invasive cancer upon evaluation of resected tissue and regional lymph nodes” [13];

- Disease-free survival (DFS), defined as the time from randomization until recurrence of the original cancer, evidence of a new primary cancer, or death from any cause [8];

- Event-free survival (EFS), defined as “the time from randomization to any of the following events: disease progression that precludes surgery, local or distant recurrence, occurrence of a second primary cancer, or death from any cause” [8]

Appendix B

| Topic | Item No. | Guide Questions/Description |

|---|---|---|

| Domain 1: Research team and reflexivity | ||

| Personal characteristics | ||

| Interviewer/facilitator | 1 | Which author/s conducted the interview or focus group? |

| Credentials | 2 | What were the researcher’s credentials? e.g., PhD, MD |

| Occupation | 3 | What was their occupation at the time of the study? |

| Gender | 4 | Was the researcher male or female? |

| Experience and training | 5 | What experience or training did the researcher have? |

| Relationship with participants | ||

| Relationship established | 6 | Was a relationship established prior to study commencement? |

| Participant knowledge of the interviewer | 7 | What did the participants know about the researcher? e.g., personal goals, reasons for doing the research |

| Interviewer characteristics | 8 | What characteristics were reported about the interviewer/facilitator? |

| Domain 2: Study design | ||

| Theoretical framework | ||

| Methodological orientation and Theory | 9 | What methodological orientation was stated to underpin the study? e.g., grounded theory, discourse analysis, ethnography, phenomenology, |

| Participant selection | ||

| Sampling | 10 | How were participants selected? e.g., purposive, convenience, consecutive, snowball |

| Method of approach | 11 | How were participants approached? e.g., face-to-face, telephone, mail, email |

| Sample size | 12 | How many participants were in the study? |

| Non-participation | 13 | How many people refused to participate or dropped out? Reasons? |

| Setting | ||

| Setting of data collection | 14 | Where was the data collected? e.g., home, clinic, workplace |

| Presence of non- | ||

| participants | 15 | Was anyone else present besides the participants and researchers? |

| Description of sample | 16 | What are the important characteristics of the sample? e.g., demographic |

| Data collection | ||

| Interview guide | 17 | Were questions, prompts, guides provided by the authors? Was it pilot tested? |

| Repeat interviews | 18 | Were repeat interviews carried out? If yes, how many? |

| Audio/visual recording | 19 | Did the research use audio or visual recording to collect the data? |

| Field notes | 20 | Were field notes made during and/or after the interview or focus group? |

| Duration | 21 | What was the duration of the interviews or focus group? |

| Data saturation | 22 | Was data saturation discussed? |

| Transcripts returned | 23 | Were transcripts returned to participants for comment and/or correction? |

| Domain 3: analysis and findings | ||

| Data analysis | ||

| Number of data coders | 24 | How many data coders coded the data? |

| Description of the coding tree | 25 | Did authors provide a description of the coding tree? |

| Derivation of themes | 26 | Were themes identified in advance or derived from the data? |

| Software | 27 | What software, if applicable, was used to manage the data? |

| Participant checking | 28 | Did participants provide feedback on the findings? |

| Reporting | ||

| Quotations presented | 29 | Were participant quotations presented to illustrate the themes/findings? Was each quotation identified? e.g., participant number |

| Data and findings consistent | 30 | Was there consistency between the data presented and the findings? |

| Clarity of major themes | 31 | Were major themes clearly presented in the findings? |

| Clarity of minor themes | 32 | Is there a description of diverse cases or discussion of minor themes? |

References

- Canadian Cancer Statistics Advisory Committee in collaboration with the Canadian Cancer Society, Statistics Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2021. Available online: https://cancer.ca/en/research/cancer-statistics/past-editions (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Akbari, M.E.; Ghelichi-Ghojogh, M.; Nikeghbalian, Z.; Karami, M.; Akbari, A.; Hashemi, M.; Nooraei, S.; Ghiasi, M.; Fararouei, M.; Moradian, F. Neoadjuvant VS adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with locally advanced breast cancer; a retrospective cohort study. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 84, 104921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteva, F.J.; Hubbard-Lucey, V.M.; Tang, J.; Pusztai, L. Immunotherapy and targeted therapy combinations in metastatic breast cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, e175–e186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forde, P.M.; Spicer, J.; Lu, S.; Provencio, M.; Mitsudomi, T.; Awad, M.M.; Felip, E.; Broderick, S.R.; Brahmer, J.R.; Swanson, S.J.; et al. Neoadjuvant Nivolumab plus Chemotherapy in Resectable Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1973–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakelee, H.; Liberman, M.; Kato, T.; Tsuboi, M.; Lee, S.H.; Gao, S.; Chen, K.N.; Dooms, C.; Majem, M.; Eigendorff, E.; et al. Perioperative Pembrolizumab for Early-Stage Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, W.F.; Ye, H.Y.; Tang, X.; Su, J.W.; Xu, K.M.; Zhong, W.Z.; Liang, Y. Adjuvant immunotherapy in early-stage resectable non–small cell lung cancer: A new milestone. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1063183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-L.; Tsuboi, M.; He, J.; John, T.; Grohe, C.; Majem, M.; Goldman, J.W.; Laktionov, K.; Kim, S.-W.; Kato, T.; et al. Osimertinib in Resected EGFR-Mutated Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1711–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administation. Clinical Trial Endpoints for the Approval of Cancer Drugs and Biologics: Guidance for Industry; U.S. Food and Drug Administation: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Royle, K.-L.; Meads, D.; Visser-Rogers, J.K.; White, I.R.; Cairns, D.A. How is overall survival assessed in randomised clinical trials in cancer and are subsequent treatment lines considered? A systematic review. Trials 2023, 24, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lux, M.P.; Ciani, O.; Dunlop, W.C.N.; Ferris, A.; Friedlander, M. The Impasse on Overall Survival in Oncology Reimbursement Decision-Making: How Can We Resolve This? Cancer Manag. Res. 2021, 13, 8457–8471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fameli, A.; Paulsson, T.; Altimari, S.; Gutierrez, B.; Cimen, A.; Nelsen, L.; Harisson, N. Looking beyond survival data: How should we assess innovation in oncology reimbursement decision making. Value Outcomes Spotlight 2023, 9, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Aitken, M.; Longosz, A.; Malde, R.; Ladha, S.; Chow, I.; Wagner, P. Evolving Oncology Endpoints: A New Horizon for Oncology Outcomes; IQVIA Institute: Durham, NC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, A.; Guddati, A.K. Clinical endpoints in oncology—A primer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2021, 11, 1121–1131. [Google Scholar]

- Suciu, S.; Eggermont, A.M.M.; Lorigan, P.; Kirkwood, J.M.; Markovic, S.N.; Garbe, C.; Cameron, D.; Kotapati, S.; Chen, T.-T.; Wheatley, K.; et al. Relapse-Free Survival as a Surrogate for Overall Survival in the Evaluation of Stage II–III Melanoma Adjuvant Therapy. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2018, 110, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, T.; Wei, Y.-W. What is the difference between overall survival, recurrence-free survival and time-to-recurrence? Br. J. Surg. 2020, 107, e634. [Google Scholar]

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Guideline on the Clinical Evaluation of Anticancer Medicinal Products; EMA: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Anastasaki, E.; Harding, T.; Ryan, J.; Seddik, A.; Dunton, K.; Becce, M.; Crossman-Barnes, C.J. HTA15 An Assessment of the Evidence Published Post-HTA for Selected HER2-Positive, Early Breast Cancer Medicines, to Address Potential HTA-Body Uncertainties. Value Health 2022, 25, S506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shameer, K.; Zhang, Y.; Jackson, D.; Rhodes, K.; Neelufer, I.K.A.; Nampally, S.; Prokop, A.; Hutchison, E.; Ye, J.; Malkov, V.A.; et al. Correlation Between Early Endpoints and Overall Survival in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Trial-Level Meta-Analysis. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 672916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thill, M.; Pisa, G.; Isbary, G. Targets for Neoadjuvant Therapy—The Preferences of Patients with Early Breast Cancer. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2016, 76, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popay, J.; Williams, G. Qualitative research and evidence-based healthcare. J. R. Soc. Med. 1998, 91, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bever, A.; Manthorne, J.; Rahim, T.; Moumin, L.; Szabo, S.M. The Importance of Disease-Free Survival as a Clinical Trial Endpoint: A Qualitative Study Among Canadian Survivors of Lung Cancer. Patient Patient-Centered Outcomes Res. 2022, 15, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssens, R.; Barbier, L.; Muller, M.; Cleemput, I.; Stoeckert, I.; Whichello, C.; Levitan, B.; Hammad, T.A.; Girvalaki, C.; Ventura, J.J.; et al. How can patient preferences be used and communicated in the regulatory evaluation of medicinal products? Findings and recommendations from IMI PREFER and call to action. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1192770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvin, R. How many interviews are enough? Do qualitative interviews in building energy consumption research produce reliable knowledge? J. Build. Eng. 2015, 1, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Arwen, B.; Johnson, L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner-Bowker, D.M.; Lamoureux, R.E.; Stokes, J.; Litcher-Kelly, L.; Galipeau, N.; Yaworsky, A.; Solomon, J.; Shields, A.L. Informing a priori sample size estimation in qualitative concept elicitation interview studies for clinical outcome assessment instrument development. Value Health 2018, 21, 839–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dworkin, S. Sample size policy for qualitative studies using indepth interviews. Arch. Sex Behav. 2012, 41, 1319–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birgisson, H.; Wallin, U.; Holmberg, L.; Glimelius, B. Survival endpoints in colorectal cancer and the effect of second primary other cancer on disease free survival. BMC Cancer 2011, 11, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid, P.; Cortes, J.; Dent, R.; Pusztai, L.; McArthur, H.; Kümmel, S.; Bergh, J.; Denkert, C.; Park, Y.H.; Hui, R.; et al. Event-free Survival with Pembrolizumab in Early Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innovent Biologics (Suzhou) Co. Ltd. Neoadjuvant and Adjuvant Therapy Studies of Sindilizumab in Resectable Lung Cancer. 2024. Available online: https://www.clinicalresearch.com/find-trials/Study/NCT05116462 (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- McLeod, S. Member Checking in Qualitative Research. 2024. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/387600910_Member_Checking_In_Qualitative_Research (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Braun, V.; Victoria, C. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada Archived–2021-Census:2A-L. 2024. Available online: https://www.statcan.gc.ca/en/statistical-programs/instrument/3901_Q2_V6 (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Gutierrez-Ibarluzea, I.; Bolanos, N.; Geissler, J.; Gorgoni, G.; Lumley, T.; Mikhael, J.; Milagre, T.; Van Poppel, H. Improving the understanding, acceptance and use of oncology–relevant endpoints in HTA body/payer decision-making. J. Oncol. Res. Ther. 2023, 8, 10181. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, H.W.; O’Donoghue, A.C.; Ferriola-Bruckenstein, K.; Tzeng, J.P.; Boudewyns, V. Patients’ Understanding of Oncology Clinical Endpoints: Environmental Scan and Focus Groups. Oncologist 2020, 25, 1060–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batchelder, L.; Guéroult-Accolas, L.; Anastasaki, E.; Dunton, K.; Lüftner, D.; Oswald, C.; Ryan, J.; Schmitt, D.; Steinerova, V.; Varghese, D.; et al. Patient preferences for treatment attributes and endpoints in neoadjuvant therapy for early-stage breast cancer. In Proceedings of the ISPOR Europe 2023, Copenhagen, Denmark, 11–15 November 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Forrest, R.; Lagarde, M.; Aggarwal, A.; Naci, H. Preferences for speed of access versus certainty of the survival benefit of new cancer drugs: A discrete choice experiment. Lancet Oncol. 2024, 25, 1635–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDA-AMC. Provide Input, Patient Input and Feedback. 2024. Available online: https://www.cda-amc.ca/patient-input-and-feedback (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Brett, B.; Wheeler, K. How to Do Qualitative Interviewing; Sage: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Regier, D.A.; Pollard, S.; McPhail, M.; Bubela, T.; Hanna, T.P.; Ho, C.; Lim, H.J.; Chan, K.; Peacock, S.J.; Weymann, D. A perspective on life-cycle health technology assessment and real-world evidence for precision oncology in Canada. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 2022, 6, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, C.; Müller, F.; Faiz, N.; King, M.T.; White, K. Patient-reported outcomes and experiences from the perspective of colorectal cancer survivors: Meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. J. Patient-Rep. Outcomes 2020, 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hortalà, C.; Selva, C.; Sola, I.; Selva, A. Experience and satisfaction of participants in colorectal cancer screening programs: A qualitative evidence synthesis. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drott, J.; Björnsson, B.; Sandström, P.; Berterö, C. Experiences of Symptoms and Impact on Daily Life and Health in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients: A Meta-synthesis of Qualitative Research. Cancer Nurs. 2022, 45, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, M.K.; Schultz, H.; Mortensen, M.B.; Birkelund, R. Decision making in the oesophageal cancer trajectory a source of tension and edginess to patients and relatives: A qualitative study. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2023, 18, 2170018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, S.; Van Hout, B.; Hawkins, N. Should We Account for Variation in Patient Preferences in Health Technology Assessment? Individual Preferences With Respect to the Characteristics and Possible Outcomes of a Healthcare Intervention May Vary. In Proceedings of the ISPOR Europe 2024, Barcelona, Spain, 17–20 November 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, S.M.; Shih, P.; Williams, J.; Degeling, C.; Mooney-Somers, J. Conducting Qualitative Research Online: Challenges and Solutions. Patient Patient-Centered Outcomes Res. 2021, 14, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Diagnosed with: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n = 33) | Breast Cancer (n = 12) | Lung Cancer (n = 11) | GI Cancer 3 (n = 10) | |

| Age at interview, mean (SD) yrs | 54.8 (12.9) | 46.3 (9.3) | 62.9 (8.9) | 56.5 (18.2) |

| Female, n (%) | 21 (64%) | 12 (100%) | 8 (72%) | 1 (10%) |

| Age at diagnosis, mean (SD) yrs | 50.4 (12.4) | 41.7 (8.5) | 57.3 (9.8) | 54.0 (13.7) |

| Disease stage; Non-liver cancers/liver cancer, n (%) | ||||

| I/0 | 10 (30%) | 6 (50%) | 2 (18%) | 2 (20%) |

| II/A | 12 (36%) | 3 (25%) | 2 (18%) | 7 (70%) |

| III/B | 7 (21%) | 1 (8%) | 5 (45%) | 1 (10%) |

| Unknown | 4 (12%) | 2 (17%) | 2 (18%) | - |

| Time from diagnosis to treatment, n (%) | ||||

| 1 month or less | 16 (49%) | 8 (67%) | 3 (27%) | 5 (50%) |

| 2–3 months | 8 (24%) | 3 (25%) | 2 (18%) | 3 (30%) |

| 4–5 months | 3 (9%) | - | 3 (27%) | - |

| More than 6 months | 1 (3%) | - | 1 (9%) | - |

| Recurrence status, n (%) | ||||

| No evidence of disease | 18 (55%) | 6 (50%) | 8 (73%) | 4 (40%) |

| Treatments received, n (%) | ||||

| Surgery | 28 (85%) | 12 (100%) | 8 (73%) | 8 (80%) |

| Surgery alone | 3 (9%) | 1 (8%) | 2 (18%) | 0 (0%) |

| Specified neo-adjuvant chem otherapy | 10 (30%) | 2 (17%) | 3 (27%) | 5 (50%) |

| Specified adjuvant chemotherapy | 9 (27%) | 4 (33%) | 3 (27%) | 2 (20%) |

| Specified neo-adjuvant radiation | 4 (12%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (18%) | 2 (20%) |

| Specified adjuvant radiation | 7 (21%) | 5 (42%) | 2 (18%) | 0 (0%) |

| Surgery in combination with any other therapy (e.g., hormone therapy, immunotherapy, undefined targeted therapy) | 12 (36%) | 6 (50%) | 4 (36%) | 2 (20%) |

| Chemotherapy | 26 (79%) | 9 (75%) | 9 (82%) | 8 (80%) |

| Radiation | 16 (48%) | 5 (42%) | 8 (72%) | 4 (40%) |

| Immunotherapy | 6 (18%) | 1 (8%) | 2 (18%) | 2 (20%) |

| Hormone therapy | 2 (6%) | 2 (17%) | - | - |

| Other unspecified targeted therapy | 4 (12%) | 3 (25%) | 1 (9%) | - |

| Currently receiving treatment, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 12 (36%) | 7 (58%) | 3 (27%) | 2 (20%) |

| No | 20 (61%) | 5 (42%) | 8 (73%) | 6 (60%) |

| Province, 1 n (%) | ||||

| Atlantic | 7 (21%) | - | 4 (36%) | 3 (30%) |

| Central | 15 (45%) | 8 (67%) | 3 (27%) | 4 (40%) |

| Prairie | 4 (12%) | 2 (17%) | 2 (18%) | - |

| Pacific | 5 (15%) | 2 (17%) | 2 (18%) | 1 (10%) |

| North | - | - | - | - |

| Race/ethnicity, 2 n (%) | ||||

| White | 28 (85%) | 11 (92%) | 10 (90%) | 7 (70%) |

| Black | - | - | - | - |

| Latin American | 3 (9%) | 1 (8%) | - | 2 (20%) |

| Asian | 2 (6%) | - | 2 (18%) | - |

| Other | 1 (3%) | 1 (8%) | - | - |

| Level of education, n (%) | ||||

| Did not complete secondary school | 2 (6%) | 1 (8%) | 1 (9%) | - |

| High school diploma or equivalent | 4 (12%) | - | 2 (18%) | 2 (20%) |

| Undergrad or college certification | 13 (39%) | 6 (50%) | 4 (36%) | 3 (30%) |

| Post-graduate degree | 12 (36%) | 5 (42%) | 4 (36%) | 3 (30%) |

| Employment status, n (%) | ||||

| Working full-time | 13 (39%) | 7 (58%) | 2 (18%) | 4 (40%) |

| Working part-time | 5 (15%) | 1 (8%) | 1 (9%) | 3 (30%) |

| Retired | 7 (21%) | 1 (8%) | 5 (45%) | 1 (10%) |

| Not working due to cancer | 3 (9%) | 1 (8%) | 2 (18%) | - |

| Not working for other reasons | 3 (9%) | 2 (17%) | 1 (9%) | - |

| Other | 2 (6%) | - | - | 2 (20%) |

| Perspectives on OS as a Trial Endpoint | |

|---|---|

| OS provides valuable information | “It helps you plan for the rest of your life. If somebody says to you, ‘You have one year to still be alive’ or ‘You have 10 years to be alive’ I think you would behave differently. You would pack these 10 years in one year. [laughs] And do everything you wanted to do … [OS] has some importance for the quality of life and what you want to achieve in your life.”—ID11, lung cancer |

| OS is easily understood | “… it’s information that we’ve been conditioned to want to know. Everyone wants to know, with a diagnosis, ‘Well, what does that mean for me? In terms of longevity, … what am I dealing with here?”—ID02, breast cancer |

| Survival is the main goal of treatment | “Yes … That was a biggie for me, just to survive as long as possible … do anything you can to make sure that you survive.”—ID22, lung cancer |

| Concerns about the statistical relevance of OS to an individual’s life | “Also, there’s just that random factor of all the other things that could lead to death. That, to me, feels like a huge variable that is not at all controlled. Anyone could die at any point in time for any measurable thing, but knowing that the cancer isn’t coming back means that that is one thing that I can eliminate from the everything else in life that I need to stress about.”—ID08, breast cancer |

| “Give me the average, and the average doesn’t necessarily pertain to me anyway, right, especially with lung cancer. I mean, I know that there’s more and more non-smokers. There’s more and more younger people, but at the beginning, it was mostly older people who were getting it. I think they do still have a big say in our average.”—ID22, lung cancer | |

| OS may take a long time to measure | “Just because of the length, it means that we’re still evaluating things that came out 10+ years ago. That scares me that if we’re waiting on certain metrics of overall survival that drugs that can save people’s lives aren’t going to be getting into people’s bodies in time.”—ID23, lung cancer |

| Strengths of Non-OS Endpoints | |

|---|---|

| Align with participants’ treatment goals | “To a cancer patient, clear margins are extremely important for your [physical] health and mental health … because if you can say, ‘Okay, there’s no more cancer in me,’ that gives you a very positive outlook on the future. So, yes, if a doctor offered me another treatment … that would say, ‘80% of people did very well with this. They had clear margins afterwards,’ yeah, I absolutely would.”—ID14, lung cancer |

| “I wanted … treatment to essentially make me disease-free; … [so] I don’t have to go through the same thing in a few years time … sometimes when you’ve just climbed that mountain and there’s another peak which you have to climb again, it’s just like, ‘Not again. I can’t do this again.’ … So, yeah, that was very important for me to … kind of anticipate what’s in the future for me when it comes to this disease.”—ID29, GI (liver) cancer | |

| Non-OS endpoints represent meaningful constructs | “I like [the] DFS [endpoint]. I don’t want to think about it in terms of a decade or 15–20 years. I really want to focus on something more achievable and relevant to me in the short-term.”—ID25, GI (liver) cancer |

| “Just knowing that there is nothing there after the surgery, I guess. I wasn’t thinking in terms of a long life; I was thinking in terms of getting through a few years.” ID36, GI (esophageal) cancer.—ID36, GI (esophageal) cancer | |

| “I’m not going to have to worry about being off work and finances, barring other things in life. I’ll be around for my kids now that they’re older, and hopefully I can see them have kids. And I can think about retirement, all those types of things. Even though the overall might not be any different, I know that ‘Okay, but the next 10 years should look awesome.’”—ID18, breast cancer | |

| Provide valuable additional clinical utility | “I am most interested in [RFS] because it weighs very heavily on me, and many cancer patients live with that sort of threat or fear for the rest of their lives, of recurrence … Knowing the rates of recurrence-free survival would be very useful information for me.”—ID02, breast cancer |

| “100% [pCR] was an important goal for me.. Literally every single study identified complete pathologic response as the deciding factor of what your prognosis was going to be. It was really important for me to know and understand what that meant. So … it was the best case outcome, but especially for me with triple negative breast cancer, the prognosis and duration of disease-free survival is astronomically different whether you get a complete pathologic response or not.”—ID08, breast cancer | |

| Access to treatment | “Definitely I would say to decision makers that, at the speed at which the science is going, if you’re waiting, as you wait, the cost is lives of people. And yes, there is uncertainty [with e.g., DFS], and I would put some boundary of certainty in the goodness and the challenges of treatment. But waiting for a very long time to make drugs appear, as somebody who has cancer, it’s kind of a little bit crazy [laughs].”—ID11, lung cancer |

| “I think that our system, drug approvals and clinical trials take way too long to be able to get approved. It’s hard to see things that are available to people in other countries that should be available to us here, but you can’t have access unless you have money. It’s frustrating.”—ID07, breast cancer | |

| Perceived drawbacks to non-OS endpoints | |

| Less information on long-term treatment impacts | “There are some long-term use impacts associated with a drug that are just unknown at the time of [non-OS endpoints] that only in time would become evident. And so that is a risk that you would have to consider before agreeing to the treatment. But I think in most circumstances, and certainly in my circumstance, the risk of the cancer killing you is greater, so you kind of take those risks and hope for the best.”—ID02, breast cancer |

| “Well, faster access would mean less information and less reassurance to offer people because there wouldn’t be the data.”—ID07, breast cancer | |

| May not meet all patient expectations | “I think one of the biggest ones (drawback of treatment measured to the standard of a non-OS endpoint) is false hope, right? If there is this mindset that it’s probably going to lead to longer overall survival and people go into that expecting it, and then it turns out it’s not the case, I think that, emotionally, psychologically that would be very hard on patients. I mean, I guess that would probably be the biggest one, especially if the quality of life is that much harder. You put your body on the line in the hopes of having these benefits, and if they don’t materialize the way you expect them to, yeah, I just wonder how much people would suffer, not just physically with symptoms they weren’t expecting but emotionally for not getting the benefits they were hoping for.”—ID23, lung cancer |

| “Overall survival would be much clearer in my mind and easier to understand than an event-free survival prediction, I think … it’s not a bad thing. I just think it’s not quite as clear, it wouldn’t be as clear in my mind what that meant exactly, whereas “survival” survival, you sort of understand that pretty basically.”—ID37, GI (stomach) cancer | |

| Valuing specific non-OS endpoints differently | |

| Assumed a better pCR would translate to longer OS, RFS, DFS or EFS—and in turn, longer OS—even when told there was no evidence supportive of this link | “Yeah, because I’m pretty sure if I keep getting the same disease and keep getting more setbacks in my health, then it would also decrease my overall survival. So, I think there’s a correlation between being disease-free and my overall survival. I think if you achieve that first step, then your overall survival also increases.”—ID29, liver cancer |

| “I believe the pathological complete response gave me a chance that I am cancer free. Which means I will … overall survival time will be very long, right.”—ID24, lung cancer | |

| The hope provided by a pCR or the assurance of a long DFS or RFS time is an important part of the appeal of non-OS endpoints for the participants. | “So I think [pCR] does give that hope that at least targeting the cancer that it’s meant to treat, it’s successful, right? And so it is kind of a sign in the right direction.”—ID06, breast cancer |

| “But if a certain treatment gives a very high incidence of recurrence-free survival, like you hope you land in that percentage, [laughs] and having that to combat some of the trauma and fear of being a cancer patient and the long-term impacts of that, yeah, I’d really like to know that information.”—ID02, breast cancer | |

| Other factors influencing perspectives on the importance of non-OS endpoints in early-stage cancers | |

| Younger participants or participants with better prognoses saw a cure as possible and having treatment options that provided a better HRQoL as a primary goal | “If the side effects of the treatment were impeding my lifestyle or my overall wellbeing … Say, for instance, they want me to go on tamoxifen, and if I’m going to have decreased libido and I’m going to be dry and I’m going to be—I don’t know—gaining 50 lbs. and … increasing my chances of getting cervical cancer, I would probably say no. Yeah, so if the side effects are going to be worse than what I am right now, then I would probably not take that extra medication.”—ID10, age 41, breast cancer |

| “Obviously, try to remove the cancer and be cancer-free because every time you think of cancer, you think of chemotherapy. You think of being nauseous. You think of being sick. So, I think the quality of life as you’re going through these treatments is very important. Obviously, at different stages of the cancer, it needs to be treated more aggressively, of course. I’m just lucky I was at that stage where I could be treated in a not so aggressive.”—ID27, stage A, GI (liver) cancer | |

| For those who had or wanted to have families, treatment goals often factored this into consideration. | “I know many, many other young women who have gone through breast cancer, especially those who had children, they were willing to do everything-like, throw the kitchen sink—and it did not matter what the studies showed. If you had equal chance of survival doing a double mastectomy versus a lumpectomy, they chose the double mastectomy even though there was no greater chance of survival, but feeling like they did everything that they could to feel like they had done everything to survive.”—ID01, breast cancer |

| Participants with poorer prognoses valued survival and having treatment options for subsequent lines of treatment | “I think if you’re talking to someone who has a high risk of recurrence or was diagnosed stage 4 de novo or has had a recurrence, I think the perspective changes. It’s not about not having the cancer come back. It’s all about ‘how long can I live?’ So, I think it really depends on the diagnosis.”—ID08, breast cancer |

| “Yes. If I were a cancer patient that my percentage wasn’t very good of surviving, I would definitely take [a drug that has outcomes expressed as event-free survival not overall survival]. I think it depends on where you are in your cancer journey.”—ID14, lung cancer | |

| For patients who had experienced relapse or never achieved ‘no evidence of disease’, survival was still a priority, but individuals often stressed the importance of maintaining HRQoL in the face of chronic disease. | “And so definitely seven years ago, I was thinking, ‘Yes, it’s on or off,’ but now I think I’ve resolved myself that it might be there for long term, and as long as there are medication to take care of it, then it’s fine.”—ID11, lung cancer |

| The treatment options available for the type and stage of cancer influenced perspectives on risk and innovation in treatments | “I think also the type of cancer that you have and what other treatment options are available. Is this the only treatment that is out there, or the only option, or is it the best chance or is it in combination with something else?”—ID06, breast cancer |

| “Yes. If I were a cancer patient that my percentage wasn’t very good of surviving, I would definitely take [a treatment that reported outcomes in terms of EFS but not OS]. I think it depends on where you are in your cancer journey.”—ID14, lung cancer | |

| “Just knowing that there is [no treatment option] there after the surgery, I guess, I wasn’t thinking in terms of a long life, I was thinking in terms of getting through a few years.”—ID36, GI (gastric) cancer | |

| Participants believed that there was a point during treatment, especially for older adults, when HRQoL would become a priority over survival | “I think it depends on the age of the person, honestly. Because if I’m an 80-year-old lady or person and you’re saying like, ‘You can live 10 more years, but those are going to be crappy years because you’re going to be fighting,’ like ‘you’re going to have to keep coming back to the hospital and dealing with that kind of stuff,’ I don’t know if I would choose to do the treatment. But like at 29, I would do anything.”—ID05, breast cancer |

| “I think knowing I was told I was cancer-free would be more important than anything. I am 65 years old, at the time 64 when I was told I was cancer-free, just being told I am cancer-free is most important”—ID36, GI (esophageal) cancer | |

| Even among those who felt DFS, RFS, and/or EFS strongly aligned with their treatment values, they remained concerned about side effects that “could be worse than the disease” or could negatively impact their lifestyle. | “Well, depending on the side effects of the treatment, what was involved in that type of thing. But if it was reasonable side effects and without too much change in your lifestyle compared to the traditional treatments, if it was a new treatment that had similar effects on you during the time that you’re being treated, if you had a better chance of a pathological complete response, I would certainly accept that.”—ID37, GI (gastric) cancer |

| Patient agency and contributions towards decision-making | |

| Participants revealed that they do not always feel empowered to advocate (or were successful in advocating) for themselves and their treatment goals | “I guess [my treatment goals changed to be] overall effects, the side effects. Like I said, my joint pain is terrible. They did not tell me that I could have heart issues, which … I’ve now had two surgeries”—ID04, breast cancer |

| “I would’ve really looked at the research and talked to people that maybe had went through it and what their opinions were, also taking into consideration what my oncologist is saying, but I probably would’ve made different choices.”—ID04, breast cancer | |

| “Yeah, I think, over time … that I learned more through my process of how to advocate, and I started doing that, actually, luckily, fairly early on in the process. I, behind the scenes, help cancer patients advocate today.”—ID20, lung cancer | |

| Many participants felt that clinicians should be making the ultimate treatment decisions for the patients | “I would want to have availability to everything within like basic safety concerns. As long as I’m reassured by competent doctors that this is safe, better, I would want to have access to new treatments.”—ID25, GI (liver) cancer |

| “My initial … I guess my initial hopes and thoughts were that I would be presented with sort of the cutting edge, with what was the most up to date and most promising. And that would be presented by a team of experts in my particular cancer. That was my hope and my expectation.”—ID21, lung cancer | |

| Messages to decision-makers | |

| Patients and clinicians should be given more treatment options by population-level decision makers | “And again, I think patients are good or getting better, or we need to allow them the space to be their own advocates and understand the risks, and if they want access to something because it’s the only thing that might work for them, that they have the right to try it, and that it’s not held up in a bureaucratic process and that they pass away in that time is … That shouldn’t be what’s happening in our system.”—ID06, breast cancer |

| A desire for decision makers to consider non-OS endpoints when making decisions about access for treatments for early-stage cancers | “Especially in a country like Canada where health care policy is trying to set for huge populations at a time, I really think there has to be more consideration for individuals’ preferences. So, if decision makers say, ‘We’re going to value overall survival more than disease-free survival,’ or vice versa, they’re making a value decision for millions of people who might feel differently. I get quite upset with this concept of the standard of care, of these boxes that people get put into because they have the best outcomes. Well, what are they counting as outcomes? What are they measuring? Those are all decisions that are subjective.”—ID23, lung cancer |

| “Make it available and that way we can have that information,” and you can have the information, or the doctors, so they can move on with [the treatment] or not.”—ID38, GI (gastric) cancer | |

| Timely and equitable access to treatments saves lives | “I kept saying, throughout this whole thing that I went through, ‘Good Lord, I would not be alive if I got this cancer 20-30 years ago. Thank goodness there’s new medicines out there’” and that pretty well answers my question.”—ID17, lung cancer |

| “I can’t imagine them waiting for overall survival to put something on the market. Then I find it amazing how many people are saying, ‘Well, the drug is available in the states, but it’s not available here yet,’ or, ‘It’s available in Ontario, but it’s not available yet in New Brunswick. It’s not covered by our insurance yet, but its covered by so-and-so’s insurance.’ There are so many things out there that … oh, yeah. It’s a tough one, but overall survival, I don’t think they can wait for that state. They just have to do it. You have to save as many of us as possible.”—ID22, lung cancer | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szabo, S.M.; Walker, S.; Griffin, E.; McMillan, A.; Bick, R.; Simbulan, F.; Ting, E.; Snow, S. “Are You Just Looking to ‘Survive’?”: A Qualitative Study of Importance of Oncology Endpoints Beyond Overall Survival in Early-Stage Cancer. Cancers 2025, 17, 3260. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193260

Szabo SM, Walker S, Griffin E, McMillan A, Bick R, Simbulan F, Ting E, Snow S. “Are You Just Looking to ‘Survive’?”: A Qualitative Study of Importance of Oncology Endpoints Beyond Overall Survival in Early-Stage Cancer. Cancers. 2025; 17(19):3260. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193260

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzabo, Shelagh M., Sarah Walker, Evelyn Griffin, Aya McMillan, Robert Bick, Frances Simbulan, Eon Ting, and Stephanie Snow. 2025. "“Are You Just Looking to ‘Survive’?”: A Qualitative Study of Importance of Oncology Endpoints Beyond Overall Survival in Early-Stage Cancer" Cancers 17, no. 19: 3260. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193260

APA StyleSzabo, S. M., Walker, S., Griffin, E., McMillan, A., Bick, R., Simbulan, F., Ting, E., & Snow, S. (2025). “Are You Just Looking to ‘Survive’?”: A Qualitative Study of Importance of Oncology Endpoints Beyond Overall Survival in Early-Stage Cancer. Cancers, 17(19), 3260. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193260