Sexual Dysfunction in Female Rectal and Anal Cancer Survivors: Pathophysiology, Clinical Management, and Integration into Survivorship Care

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Physiology of Female Sexuality and Oncologic Impact

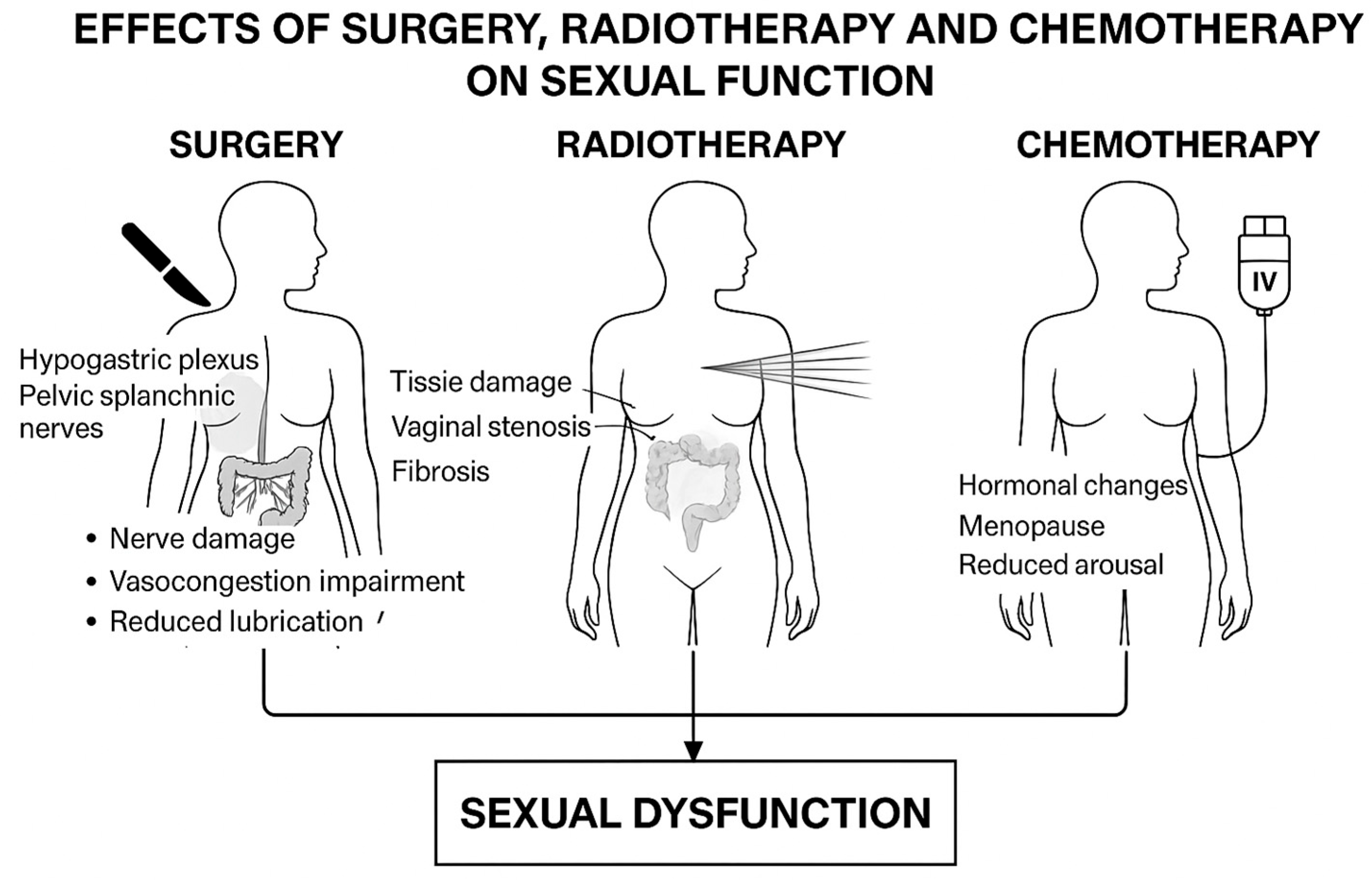

3. Rectal and Anal Cancer Surgery and Sexual Dysfunction

4. Radiotherapy/Chemoradiotherapy: Late Effects on Sexual Function

5. Psychological and Relational Aspects

6. Assessment Tools and Limitations in Oncologic Female Populations

7. Therapeutic and Rehabilitative Strategies

8. Discussion

9. Strengths and Limitations

10. Conclusions and Future Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Canty, J.; Stabile, C.; Milli, L.; Seidel, B.; Goldfrank, D.; Carter, J. Sexual Function in Women with Colorectal/Anal Cancer. Sex. Med. Rev. 2019, 7, 202–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pedersen, E.S.L.; Verschoor, D.; Segelov, E. Incidence and burden of anal cancer—Time to fight the growing disparities. ESMO Gastrointest. Oncol. 2025, 100147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, L.S.; O’Riordan, L.; Natale, C.; Jenkins, L.C. Enhancing Sexual Health for Cancer Survivors. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book. 2025, 45, e472856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azadzoi, K.M.; Siroky, M.B. Neurologic factors in female sexual function and dysfunction. Korean J. Urol. 2010, 51, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Graziottin, A.; Gambini, D.; Perelman, M.A. Female sexual dysfunctions: Future of medical therapy. In Advances in Sexual Medicine: Drug Discovery Issues; Abdel-Hamid, I.A., Ed.; Research Signpost: Trivandrum, India, 2009; pp. 403–432. ISBN 978-81-308-0307-4. [Google Scholar]

- Molina, J.R.; Barton, D.L.; Loprinzi, C.L. Chemotherapy-Induced Ovarian Failure: Manifestations and Management. Drug Saf. 2005, 28, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chew, M.H.; Yeh, Y.T.; Lim, E.; Seow-Choen, F. Pelvic autonomic nerve preservation in radical rectal cancer surgery: Changes in the past 3 decades. Gastroenterol. Report. 2016, 4, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varytė, G.; Bartkevičienė, D. Pelvic Radiation Therapy Induced Vaginal Stenosis: A Review of Current Modalities and Recent Treatment Advances. Medicina 2021, 57, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Flynn, K.E.; Reese, J.B.; Jeffery, D.D.; Abernethy, A.P.; Lin, L.; Shelby, R.A.; Porter, L.S.; Dombeck, C.B.; Weinfurt, K.P. Patient experiences with communication about sex during and after treatment for cancer. Psychooncology 2012, 21, 594–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, R.; Brown, C.; Heiman, J.; Leiblum, S.; Meston, C.; Shabsigh, R.; Ferguson, D.; D’Agostino, R., Jr. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J. Sex. Marital. Ther. 2000, 26, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, P.T.; Groenvold, M.; Klee, M.C.; Thranov, I.; Petersen, M.A.; Machin, D. Early-stage cervical carcinoma, radical hysterectomy, and sexual function. A longitudinal study. Cancer 2014, 100, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, P.T.; Groenvold, M.; Klee, M.C.; Thranov, I.; Petersen, M.A.; Machin, D. Longitudinal study of sexual function and vaginal changes after radiotherapy for cervical cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2003, 56, 937–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, M.; White, K.; Hillman, R.J.; Rutherford, C. The impact of anal cancer treatment on female sexuality and intimacy: A systematic review. Support. Care Cancer 2025, 33, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stead, M.L.; Fallowfield, L.; Selby, P.; Brown, J.; Wingate, H. Psychosexual function and impact of gynaecological cancer. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2007, 21, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindau, S.T.; Gavrilova, N. Sex, health, and years of sexually active life gained due to good health: Evidence from two US population-based cross-sectional surveys of ageing. BMJ 2010, 340, c810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruheim, K.; Tveit, K.M.; Skovlund, E.; Balteskard, L.; Carlsen, E.; Fosså, S.D.; Guren, M.G. Sexual function in females after radiotherapy for rectal cancer. Acta Oncol. 2010, 49, 826–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanft, T.; Day, A.T.; Goldman, M.; Ansbaugh, S.; Armenian, S.; Baker, K.S.; Ballinger, T.J.; Demark-Wahnefried, W.; Fairman, N.P.; Feliciano, J.; et al. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Survivorship, Version 2.2024. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2024, 22, 648–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacerdoti, R.C.; Laganà, L.; Koopman, C. Altered Sexuality and Body Image after Gynecological Cancer Treatment: How Can Psychologists Help? Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2010, 41, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Weaver, K.L.; Grimm, L.M., Jr.; Fleshman, J.W. Changing the Way We Manage Rectal Cancer-Standardizing TME from Open to Robotic (Including Laparoscopic). Clin. Colon. Rectal Surg. 2015, 28, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Baader, B.; Herrmann, M. Topography of the pelvic autonomic nervous system and its potential impact on surgical intervention in the pelvis. Clin. Anat. 2003, 16, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bregendahl, S.; Emmertsen, K.J.; Lindegaard, J.C.; Laurberg, S. Urinary and sexual dysfunction in women after resection with and without preoperative radiotherapy for rectal cancer: A population-based cross-sectional study. Color. Dis. 2015, 17, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celentano, V.; Cohen, R.; Warusavitarne, J.; Faiz, O.; Chand, M. Sexual dysfunction following rectal cancer surgery. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2017, 32, 1523–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaedcke, J.; Sahrhage, M.; Ebeling, M.; Azizian, A.; Rühlmann, F.; Bernhardt, M.; Grade, M.; Bechstein, W.O.; Germer, C.T.; Grützmann, R.; et al. Prognosis and quality of life in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer after abdominoperineal resection in the CAO/ARO/AIO-04 randomized phase 3 trial. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim, N.K.; Kim, Y.W.; Cho, M.S. Total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer with emphasis on pelvic autonomic nerve preservation: Expert technical tips for robotic surgery. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 24, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; He, X.; Tong, S.; Zheng, Y. Risk factors for sexual dysfunction after rectal cancer surgery in 948 consecutive patients: A prospective cohort study. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 47, 2087–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, R.M.; Vermeer, W.M.; Creutzberg, C.L.; Mens, J.W.; Nout, R.A.; Ter Kuile, M.M. Qualitative accounts of patients’ determinants of vaginal dilator use after pelvic radiotherapy. J. Sex. Med. 2015, 12, 764–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirchheiner, K.; Nout, R.A.; Lindegaard, J.C.; Haie-Meder, C.; Mahantshetty, U.; Segedin, B.; Jürgenliemk-Schulz, I.M.; Hoskin, P.J.; Rai, B.; Dörr, W.; et al. Dose-effect relationship and risk factors for vaginal stenosis after definitive radio(chemo)therapy with image-guided brachytherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer in the EMBRACE study. Radiother. Oncol. 2016, 118, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delanian, S.; Lefaix, J.L.; Pradat, P.F. Radiation-induced neuropathy in cancer survivors. Radiother. Oncol. 2012, 105, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hymel, R.; Jones, G.C.; Simone, C.B., II. Whole pelvic intensity-modulated radiotherapy for gynecological malignancies: A review of the literature. Crit. Rev. Oncol./Hematol. 2015, 94, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Naren, G.; Guo, J.; Bai, Q.; Fan, N.; Nashun, B. Reproductive and developmental toxicities of 5-fluorouracil in model organisms and humans. Expert. Rev. Mol. Med. 2022, 24, e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wu, C.; Wu, T.; Chen, D.; Wei, S.; Tang, W.; Xue, L.; Xiong, J.; Huang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Chen, Y.; et al. The effects and mechanism of taxanes on chemotherapy-associated ovarian damage: A review of current evidence. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1025018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Reimer, N.; Brodesser, D.; Ratiu, D.; Zubac, D.; Lehmann, H.C.; Baumann, F.T. Initial observations on sexual dysfunction as a symptom of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Ger. Med. Sci. 2023, 21, Doc08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stone, M.A.; Lissenberg-Witte, B.I.; de Bree, R.; Hardillo, J.A.; Lamers, F.; Langendijk, J.A.; Leemans, C.R.; Takes, R.P.; Jansen, F.; Verdonck-de Leeuw, I.M. Changes in Sexuality and Sexual Dysfunction over Time in the First Two Years After Treatment of Head and Neck Cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 4755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mosher, C.E.; Winger, J.; Given, B.; Helft, P.R.; O’NEil, B.H. Mental health outcomes during colorectal cancer survivorship: A review. Psychooncology 2016, 25, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, V.; Oveisi, N.; McTaggart-Cowan, H.; Loree, J.M.; Murphy, R.A.; De Vera, M.A. Colorectal Cancer and Onset of Anxiety and Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 8751–8766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, A.; Li, H.; Shen, M.; Li, D.; Shu, D.; Liu, Y.; Tang, H.; Li, K.; Peng, Y.; Liu, S. Association of depressive symptoms and sleep disturbances with survival among US adult cancer survivors. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedict, C.; Philip, E.J.; Baser, R.E.; Carter, J.; Schuler, T.A.; Jandorf, L.; DuHamel, K.; Nelson, C. Body image and sexual function in women after treatment for anal and rectal cancer. Psychooncology 2016, 25, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Meyer, I.; Richter, H.E. Impact of fecal incontinence and its treatment on quality of life in women. Womens Health 2015, 11, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Unseld, M.; Zeilinger, E.L.; Fellinger, M.; Lubowitzki, S.; Krammer, K.; Nader, I.W.; Hafner, M.; Kitta, A.; Adamidis, F.; Masel, E.K.; et al. Prevalence of pain and its association with symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety and distress in 846 cancer patients: A cross sectional study. Psychooncology 2021, 30, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Camejo, N.; Montenegro, C.; Amarillo, D.; Castillo, C.; Krygier, G. Addressing sexual health in oncology: Perspectives and challenges for better care at a national level. Ecancermedicalscience 2024, 18, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, M.; Chan, C.W.H.; Chow, K.M.; Xiao, J.; Choi, K.C. A systematic review and meta-analysis of couple-based intervention on sexuality and the quality of life of cancer patients and their partners. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 1607–1630, Erratum in Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 5045.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, C.J.; Yang, G.S.; Syrjala, K. Symptom experiences in colorectal cancer survivors after cancer treatments: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Nurs. 2020, 43, E132–E158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basson, R. Sexual function of women with chronic illness and cancer. Women’s Health 2010, 6, 407–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedict, C.; Shaffer, K.M.; Wirtz, M.R.; Ford, J.S.; Reese, J.B. Current considerations in interventions to address sexual function and improve care for women with cancer. Curr. Sex. Health Rep. 2022, 14, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, H.B.; Carneiro, B.C.; Vasconcelos, P.A.; Pereira, R.; Quinta-Gomes, A.L.; Nobre, P.J. Promoting sexual health in colorectal cancer patients and survivors: Results from a systematic review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, L.; Caruso, R.; Riba, M.; Lloyd-Williams, M.; Kissane, D.; Rodin, G.; McFarland, D.; Campos-Ródenas, R.; Zachariae, R.; Santini, D.; et al. Anxiety and depression in adult cancer patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline. ESMO Open 2023, 8, 101155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyø, A.; Emmertsen, K.J.; Laurberg, S. Female sexual problems after treatment for colorectal cancer–A population-based study. Color. Dis. 2019, 21, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traa, M.J.; de Vries, J.; Roukema, J.A.; Den Oudsten, B.L. Sexual (dys)function and the quality of sexual life in patients with colorectal cancer: A systematic review. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkinson, K.; Butow, P.; Hunt, G.E.; Wyse, R.; Hobbs, K.M.; Wain, G. Life after cancer: Couples’ and partners’ psychological adjustment and supportive care needs. Support. Care Cancer 2007, 15, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baser, R.E.; Li, Y.; Carter, J. Psychometric validation of the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) in cancer survivors. Cancer 2012, 118, 4606–4618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, T.X.M.; Park, J.; Lee, J.; Jung, Y.S.; Chang, Y.; Cho, H. Utility of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) to measure primary health outcomes in cancer patients: A systematic review. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 1723–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrigan, K.L.; Rooney, M.K.; De, B.; Ludmir, E.D.; Das, P.; Smith, G.L.; Taniguchi, C.; Minsky, B.D.; Koay, E.J.; Koong, A.; et al. Patient-Reported Sexual Function in Long-Term Survivors of Anal Cancer Treated With Definitive Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy and Concurrent Chemotherapy. Pract. Radiat. Oncol. 2022, 12, e397–e405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sodergren, S.C.; Edwards, R.; Krishnatry, R.; Guren, M.G.; Dennis, K.; Franco, P.; de Felice, F.; Darlington, A.S.; Vassiliou, V. Improving our understanding of the quality of life of patients with metastatic or recurrent/persistent anal cancer: A systematic review. Support. Care Cancer 2025, 33, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miguel, C.A.; Cavasotto, L.C.; López Sartorio, C.; Marcolini, N.; Gayet, F.; Coronel, M.F. Prevalencia de la neuropatía inducida por oxaliplatino: Diferencias asociadas al sexo [Prevalence of oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy: Sex-related differences]. Medicina 2025, 85, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lorenz, T.K. Interactions between inflammation and female sexual desire and arousal function. Curr. Sex. Health Rep. 2019, 11, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cercek, A.; Lumish, M.; Sinopoli, J.; Weiss, J.; Shia, J.; Lamendola-Essel, M.; El Dika, I.H.; Segal, N.; Shcherba, M.; Sugarman, R.; et al. PD-1 blockade in mismatch repair–deficient, locally advanced rectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 2363–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; Capdevila, J.; Gilbert, D.; Kim, S.; Dahan, L.; Kayyal, T.; Fakih, M.; Demols, A.; Jensen, L.H.; Spindler, K.-L.; et al. LBA42 POD1UM-202: Phase II study of retifanlimab in patients (pts) with squamous carcinoma of the anal canal (SCAC) who progressed following platinum-based chemotherapy. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31 (Suppl. 4), S1170–S1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; Anandappa, G.; Capdevila, J.; Dahan, L.; Evesque, L.; Kim, S.; Saunders, M.P.; Gilbert, D.C.; Jensen, L.H.; Samalin, E.; et al. A phase II study of retifanlimab (INCMGA00012) in patients with squamous carcinoma of the anal canal who have progressed following platinum-based chemotherapy (POD1UM-202). ESMO Open. 2022, 7, 100529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rao, S.; Samalin-Scalzi, E.; Evesque, L.; Ben Abdelghani, M.; Morano, F.; Roy, A.; Dahan, L.; Tamberi, S.; Dhadda, A.S.; Saunders, M.P.; et al. Retifanlimab with carboplatin and paclitaxel for locally recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal (POD1UM-303/InterAACT-2): A global, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2025, 405, 2144–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, J.; Stabile, C.; Seidel, B.; Baser, R.E.; Goldfarb, S.; Goldfrank, D.J. Vaginal and sexual health treatment strategies within a female sexual medicine program for cancer patients and survivors. J. Cancer Surviv. 2017, 11, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Juravic, M.; Mazza, G.; Krychman, M.L. Vaginal dilators: Issues and answers. Sex. Med. Rev. 2021, 9, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosch, N.M.; Kalkdijk-Dijkstra, A.J.; van Westreenen, H.L.; Broens, P.; Pierie, J.; van der Heijden, J.; Klarenbeek, B.R.; FORCE trial group. Pelvic floor rehabilitation after rectal cancer surgery: One-year follow-up of a multicenter randomized clinical trial (FORCE trial). Ann. Surg. 2024, 281, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, A.C.N.L.; Palacios-Ceña, D.; Pena, C.C.; Duarte, T.B.; de la Ossa, A.M.P.; Jorge, C.H. Conservative non-pharmacological interventions in women with pelvic floor dysfunction: A systematic review of qualitative studies. BMC Women’s Health 2022, 22, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Treatment | Pathophysiological Mechanisms | Main Reported Dysfunctions | Prevalence Data | Management and Rehabilitation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery (LAR, APR, TME) | Injury to hypogastric plexus and pelvic autonomic nerves; anatomical alterations; stoma presence | Reduced lubrication, dyspareunia, decreased desire, loss of genital sensitivity, altered body image | 19–62% postoperative dysfunction; up to 40% cessation of sexual activity | Nerve-sparing techniques, structured preoperative counseling, pelvic floor physiotherapy, psychosexual support |

| Radiotherapy/Chemoradiotherapy | Tissue fibrosis, hypoxia, reduced vascularization, mucosal atrophy; late neuropathy | Vaginal dryness, stenosis, dyspareunia, reduced elasticity, pain | Vaginal dryness: 50% vs. 24% (RT+surgery vs. surgery alone); vaginal stenosis up to 88% | Vaginal dilators, regular sexual activity, moisturizers/lubricants, local estrogen therapy (if not contraindicated) |

| Chemotherapy | Premature menopause due to ovarian toxicity; peripheral neuropathy (oxaliplatin, taxanes); endocrine alterations | Reduced desire, impaired lubrication, infertility, dyspareunia, diminished orgasmic response | >60% of survivors with FSFI < 26.5; persistent dysfunction common | Hormonal replacement (if indicated), endocrine support, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), mindfulness, sexual rehabilitation |

| Immunotherapy (dMMR rectal cancer, advanced SCAC) | Organ-preserving approach; lower cumulative toxicity; preservation of pelvic anatomy | Direct data lacking; expected lower risk of dysfunction | Early trials (dostarlimab, retifanlimab): high response rates, no ≥G3 toxicities, no sexual function data | Prospective monitoring needed; patient counseling and sexual health follow-up recommended |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Drittone, D.; Specchia, M.; Mazzotti, E.; Mazzuca, F. Sexual Dysfunction in Female Rectal and Anal Cancer Survivors: Pathophysiology, Clinical Management, and Integration into Survivorship Care. Cancers 2025, 17, 3150. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193150

Drittone D, Specchia M, Mazzotti E, Mazzuca F. Sexual Dysfunction in Female Rectal and Anal Cancer Survivors: Pathophysiology, Clinical Management, and Integration into Survivorship Care. Cancers. 2025; 17(19):3150. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193150

Chicago/Turabian StyleDrittone, Denise, Monia Specchia, Eva Mazzotti, and Federica Mazzuca. 2025. "Sexual Dysfunction in Female Rectal and Anal Cancer Survivors: Pathophysiology, Clinical Management, and Integration into Survivorship Care" Cancers 17, no. 19: 3150. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193150

APA StyleDrittone, D., Specchia, M., Mazzotti, E., & Mazzuca, F. (2025). Sexual Dysfunction in Female Rectal and Anal Cancer Survivors: Pathophysiology, Clinical Management, and Integration into Survivorship Care. Cancers, 17(19), 3150. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193150