Understanding Contemporary Endometrial Cancer Survivorship Issues: Umbrella Review and Healthcare Professional Survey †

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- (i)

- What survivorship outcomes have been reported in endometrial cancer survivors; and

- (ii)

- How have these survivorship outcomes been measured in research?

- (i)

- Do HCPs perceive each survivorship outcome identified from the umbrella review as being relevant for this population; and

- (ii)

- Are there additional survivorship issues that HCPs view as being relevant that were not identified in the umbrella review?

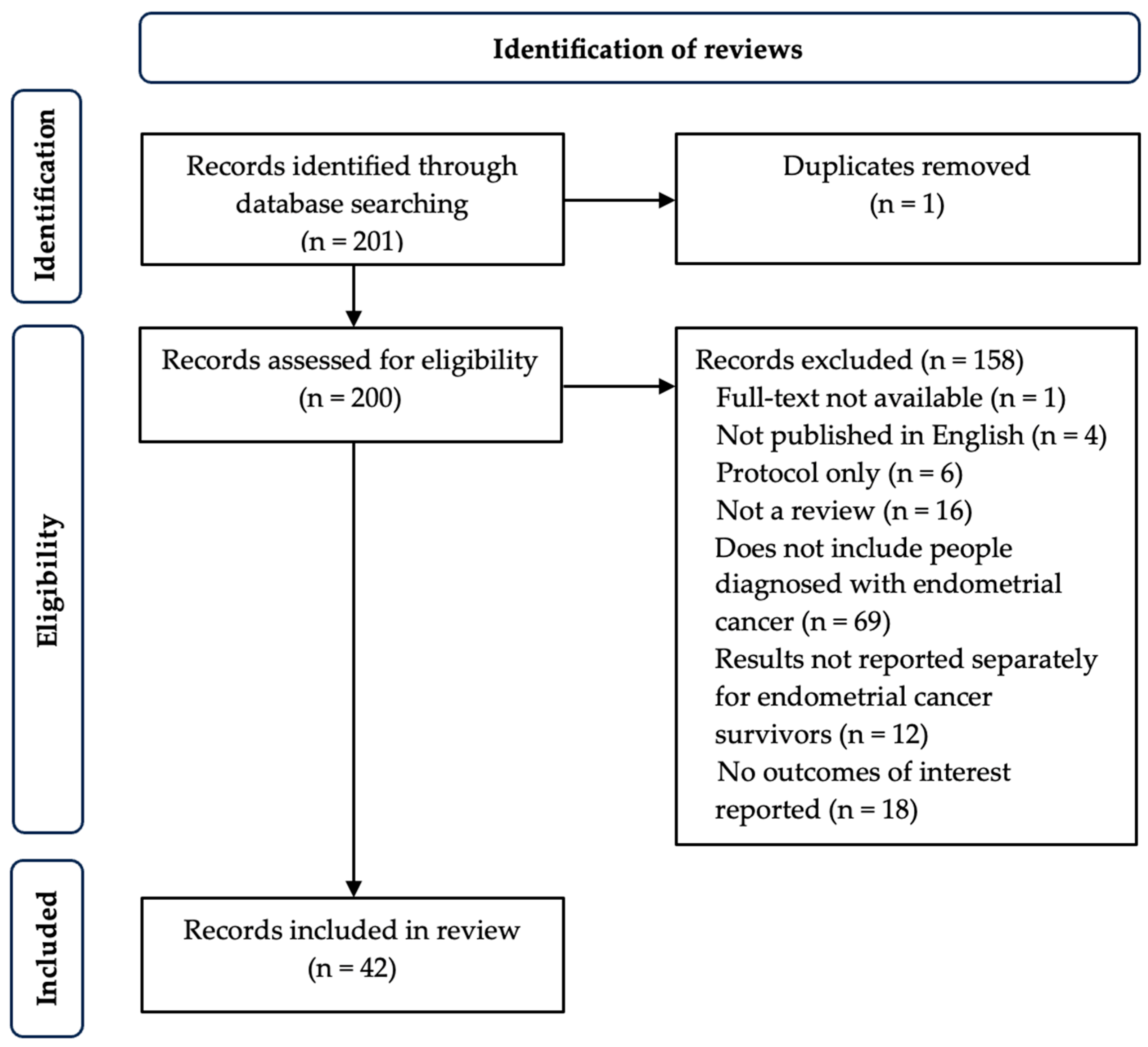

2.1. Stage 1: Umbrella Review

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.1.2. Search Strategy

2.1.3. Screening and Selection

2.1.4. Data Extraction

2.1.5. Data Synthesis

2.2. Stage 2: Healthcare Professional Survey

2.2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2.2. Data Collection

2.2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Stage 1: Umbrella Review

3.1.1. Review Characteristics

3.1.2. Survivorship Outcomes

3.1.3. Physical Health Outcomes

3.1.4. Fertility-Related Outcomes

3.1.5. Quality of Life

3.1.6. Treatment-Related Toxicities

3.1.7. Mental Health Outcomes

3.2. Stage 2: Healthcare Professional Survey

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HCP | Healthcare professional |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute |

| ANZGOG | Australia New Zealand Gynaecological Oncology Group |

| REDcap | Research Electronic Data Capture |

| EORTC QLQ-EN24 | European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Endometrial cancer module |

| FACT-En | Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Endometrial |

| FACIT-Fatigue | Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue |

| LENT-SOMA | Late Effects Normal Tissues-Subjective, Objective, Management Analytic |

| CTCAE | Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events |

References

- Ferlay, J.E.M.; Lam, F.; Laversanne, M.; Colombet, M.; Mery, L.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2024. Available online: https://gco.iarc.who.int/today (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Cancer Australia. Uterine Sarcoma. Canberra: Australian Government. 2024. Available online: https://www.canceraustralia.gov.au/cancer-types/endometrial-cancer/uterine-cancer-statistics (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Sheikh, M.A.; Althouse, A.D.; Freese, K.E.; Soisson, S.; Edwards, R.P.; Welburn, S.; Sukumvanich, P.; Comerci, J.; Kelley, J.; LaPorte, R.E.; et al. USA endometrial cancer projections to 2030: Should we be concerned? Future Oncol. 2014, 10, 2561–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yuan, Y.; Zhu, R.; Zhang, X. Time trend of global uterine cancer burden: An age-period-cohort analysis from 1990 to 2019 and predictions in a 25-year period. BMC Women’s Health 2023, 23, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine; National Research Council. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition; Hewitt, M., Greenfield, S., Stovall, E., Eds.; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; p. 534. [Google Scholar]

- Shisler, R.; Sinnott, J.A.; Wang, V.; Hebert, C.; Salani, R.; Felix, A.S. Life after endometrial cancer: A systematic review of patient-reported outcomes. Gynecol. Oncol. 2018, 148, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabian, A.; Krug, D.; Alkatout, I. Radiotherapy and its intersections with surgery in the management of localized gynecological malignancies: A comprehensive overview for clinicians. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 10, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concin, N.; Matias-Guiu, X.; Vergote, I.; Cibula, D.; Mirza, M.R.; Marnitz, S.; Ledermann, J.; Bosse, T.; Chargari, C.; Fagotti, A.; et al. ESGO/ESTRO/ESP guidelines for the management of patients with endometrial carcinoma. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2021, 31, 12–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güven, D.C.; Thong, M.S.; Arndt, V. Survivorship outcomes in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: A scoping review. J. Cancer Surviv. 2025, 19, 806–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.F.R.; Godfrey, C.; Holly, C.; Khalil, H.; Tungpunkom, P. Umbrella Reviews. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E.L.C., Porritt, K., Pilla, B., Jordan, Z., Eds.; JBI, 2020; Available online: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- Lee, A.; Leung, S. Health Outcomes. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Michalos, A.C., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 2730–2735. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. About Cancer Survivorship Research: Survivorship Definitions; National Cancer Institute: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Microsoft Corporation. Microsoft Excel; Microsoft Corporation: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- The EndNote Team. EndNote, 20th ed.; Clarivate: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; O’Neal, L.; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerstl, B.; Sullivan, E.; Vallejo, M.; Koch, J.; Johnson, M.; Wand, H.; Webber, K.; Ives, A. Reproductive outcomes following treatment for a gynecological cancer diagnosis: A systematic review. J. Cancer Surviv. 2019, 13, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koskas, M.; Uzan, J.; Luton, D.; Rouzier, R.; Daraï, E. Prognostic factors of oncologic and reproductive outcomes in fertility-sparing management of endometrial atypical hyperplasia and adenocarcinoma: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil. Steril. 2014, 101, 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prodromidou, A.; Lekka, S.; Fotiou, A.; Psomiadou, V.; Iavazzo, C. The evolving role of targeted metformin administration for the prevention and treatment of endometrial cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2021, 50, 102164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russa, M.L.A.; Liakou, C.; Burbos, N. Ultra-minimally invasive approaches for endometrial cancer treatment: Review of the literature. Minerva Medica 2021, 112, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirabeau-Beale, K.L.; Viswanathan, A.N. Quality of life (QOL) in women treated for gynecologic malignancies with radiation therapy: A literature review of patient-reported outcomes. Gynecol. Oncol. 2014, 134, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennen, R.; Lin, K.Y.; Denehy, L.; Frawley, H.C. The effect of pelvic floor muscle interventions on pelvic floor dysfunction after gynecological cancer treatment: A systematic review. Phys. Ther. Rehabil. J. 2020, 100, 1357–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SGO Clinical Practice Endometrial Cancer Working Group; Burke, W.M.; Orr, J.; Leitao, M.; Salom, E.; Gehrig, P.; Olawaiye, A.B.; Brewer, M.; Boruta, D.; Herzog, T.J.; et al. Endometrial cancer: A review and current management strategies: Part II. Gynecol. Oncol. 2014, 134, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anker, M.S.; Holcomb, R.; Muscaritoli, M.; von Haehling, S.; Haverkamp, W.; Jatoi, A.; Morley, J.E.; Strasser, F.; Landmesser, U.; Coats, A.J.S.; et al. Orphan disease status of cancer cachexia in the USA and in the European Union: A systematic review. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2019, 10, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alanazi, M.T.; Alanazi, N.T.; Alfadeel, M.A.; Bugis, B.A. Sleep deprivation and quality of life among uterine cancer survivors: Systematic review. Support Care Cancer 2022, 30, 2891–2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, D.C.; Luo, P.H.; Huang, S.X.; Wang, H.L.; Huang, J.F. Safety and efficacy of pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib versus pembrolizumab and lenvatinib monotherapies in cancers: A systematic review. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 91, 107281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Liang, M.; Min, J. Efficacy and safety of bevacizumab-combined chemotherapy for advanced and recurrent endometrial cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Balk. Med. J. 2021, 38, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charo, L.M.; Plaxe, S.C. Recent advances in endometrial cancer: A review of key clinical trials from 2015 to 2019. F1000Research 2019, 8, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindqvist, E.; Wedin, M.; Fredrikson, M.; Kjølhede, P. Lymphedema after treatment for endometrial cancer—A review of prevalence and risk factors. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2017, 211, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niikura, H.; Tsuji, K.; Tokunaga, H.; Shimada, M.; Ishikawa, M.; Yaegashi, N. Sentinel node navigation surgery in cervical and endometrial cancer: A review. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 49, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zorzato, P.C.; Bosco, M.; Franchi, M.P.; Mariani, A.; Cianci, S.; Garzon, S.; Uccella, S. Sentinel lymph node for endometrial cancer treatment: Review of the literature. Minerva Medica 2021, 112, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piatek, S.; Michalski, W.; Sobiczewski, P.; Bidzinski, M.; Szewczyk, G. The results of different fertility-sparing treatment modalities and obstetric outcomes in patients with early endometrial cancer and atypical endometrial hyperplasia: Case series of 30 patients and systematic review. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2021, 263, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerli, S.; Spanò, F.; Di Renzo, G.C. Endometrial carcinoma in women 40 year old or younger: A case report and literature review. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2014, 18, 1973–1978. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Reilly, M.; Bruner, D.W.; Bai, J.; Hu, Y.J.; Yeager, K.A. Obesity and patient-reported sexual health outcomes in gynecologic cancer survivors: A systematic review. Res. Nurs. Health 2022, 45, 664–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwman, F.; Smits, A.; Lopes, A.; Das, N.; Pollard, A.; Massuger, L.; Bekkers, R.; Galaal, K. The impact of BMI on surgical complications and outcomes in endometrial cancer surgery—An institutional study and systematic review of the literature. Gynecol. Oncol. 2015, 139, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, C.A.; Pothuri, B.; Arend, R.C.; Backes, F.J.; Gehrig, P.A.; Soliman, P.T.; Thompson, J.S.; Urban, R.R.; Burke, W.M. Endometrial cancer: A Society of Gynecologic Oncology evidence-based review and recommendations. Gynecol. Oncol. 2021, 160, 817–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.A.; Lee, D.H.; Kim, S.W.; Lee, S.H. Comparative safety and effectiveness of robot-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy versus conventional laparoscopy and laparotomy for endometrial cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2016, 42, 1303–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaseshan, A.S.; Felton, J.; Roque, D.; Rao, G.; Shipper, A.G.; Sanses, T.V.D. Pelvic floor disorders in women with gynecologic malignancies: A systematic review. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2018, 29, 459–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allanson, E.R.; Peng, Y.; Choi, A.; Hayes, S.; Janda, M.; Obermair, A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of sarcopenia as a prognostic factor in gynecological malignancy. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2020, 30, 1791–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, I.D.; Sangha, A.; Lucas, G.; Wiseman, T. Assessment of sexual difficulties associated with multi-modal treatment for cervical or endometrial cancer: A systematic review of measurement instruments. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 143, 664–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, I.; Machida, H.; Morisada, T.; Terao, Y.; Tabata, T.; Mikami, M.; Hirashima, Y.; Kobayashi, Y.; Baba, T.; Nagase, S. Effects of a fertility-sparing re-treatment for recurrent atypical endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer: A systematic literature review. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2023, 34, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giampaolino, P.; Cafasso, V.; Boccia, D.; Ascione, M.; Mercorio, A.; Viciglione, F.; Palumbo, M.; Serafino, P.; Buonfantino, C.; De Angelis, M.C.; et al. Fertility-sparing approach in patients with endometrioid endometrial cancer grade 2 stage IA (FIGO): A qualitative systematic review. BioMed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 4070368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera Cappelletti, E.; Humann, J.; Torrejón, R.; Gambadauro, P. Chances of pregnancy and live birth among women undergoing conservative management of early-stage endometrial cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2022, 28, 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zisi, M.; Zygouris, D.; Tsonis, O.; Papadimitriou, S.; George, M.; Kalantaridou, S.; Paschopoulos, M. Uterine sparing management in patients with endometrial cancer: A narrative literature review. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022, 42, 823–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzon, S.; Uccella, S.; Zorzato, P.C.; Bosco, M.; Franchi, M.P.; Student, V.; Mariani, A. Fertility-sparing management for endometrial cancer: Review of the literature. Minerva Medica 2021, 112, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zhang, W.; Feng, L.; Gao, W. Comparison of fertility-sparing treatments in patients with early endometrial cancer and atypical complex hyperplasia: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Medicine 2017, 96, e8034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurelli, G.; Falcone, F.; Scaffa, C.; Messalli, E.M.; Del Giudice, M.; Losito, S.; Greggi, S. Fertility-sparing management of low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma: Analysis of an institutional series and review of the literature. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2015, 195, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arendas, K.; Aldossary, M.; Cipolla, A.; Leader, A.; Leyland, N.A. Hysteroscopic resection in the management of early-stage endometrial cancer: Report of 2 cases and review of the literature. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2015, 22, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trojano, G.; Olivieri, C.; Tinelli, R.; Damiani, G.R.; Pellegrino, A.; Cicinelli, E. Conservative treatment in early stage endometrial cancer: A review. Acta Bio-Medica L’ateneo Parm. 2019, 90, 405–410. [Google Scholar]

- Tanos, P.; Dimitriou, S.; Gullo, G.; Tanos, V. Biomolecular and genetic prognostic factors that can facilitate fertility-sparing treatment (FST) decision making in early stage endometrial cancer (ES-EC): A systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coakley, K.; Wolford, J.; Tewari, K.S. Fertility preserving treatment for gynecologic malignancies: A review of recent literature. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 32, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.L.; Du, Z.Q.; Zhang, X.; Yao, Z.; Liang, Y.Q.; Zhao, S.F. Fertility-preserving treatment in patients with early-stage endometrial cancer: A protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2021, 100, e27961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, N.D.; Kennard, J.A.; Ahmad, S. Fertility preserving options for gynecologic malignancies: A review of current understanding and future directions. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2018, 132, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suri, V.; Arora, A. Management of Endometrial Cancer: A Review. Rev. Recent Clin. Trials 2015, 10, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, H.; Zeng, D.; Ou, H.; Tang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhong, H. Laparoscopic treatment of endometrial cancer: Systematic review. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2013, 20, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, C.L.; Guerrero-Urbano, T.; White, I.; Taylor, B.; Kristeleit, R.; Montes, A.; Fox, L.; Beyer, K.; Sztankay, M.; Ratti, M.M.; et al. Assessing the quality of patient-reported outcome measurements for gynecological cancers: A systematic review. Future Oncol. 2023, 19, 663–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassem, L.; Abdel-Rahman, O. Targeting mTOR pathway in gynecological malignancies: Biological rationale and systematic review of published data. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2016, 108, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.J.; Hollingdrake, O.; Bui, U.; Nekhlyudov, L.; Hart, N.H.; Lui, C.W.; Feuerstein, M. Evolving landscape of cancer survivorship research: An analysis of the Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 2007–2020. J. Cancer Surviv. 2021, 15, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wortman, B.G.; Creutzberg, C.L.; Putter, H.; Jürgenliemk-Schulz, I.M.; Jobsen, J.J.; Lutgens, L.C.H.W.; van der Steen-Banasik, E.M.; Mens, J.W.M.; Slot, A.; Kroese, M.C.S.; et al. Ten-year results of the PORTEC-2 trial for high-intermediate risk endometrial carcinoma: Improving patient selection for adjuvant therapy. Br. J. Cancer 2018, 119, 1067–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Boer, S.M.; Powell, M.E.; Mileshkin, L.; Katsaros, D.; Bessette, P.; Haie-Meder, C.; Ottevanger, P.B.; Ledermann, J.A.; Khaw, P.; D’Amico, R.; et al. Adjuvant chemoradiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone in women with high-risk endometrial cancer (PORTEC-3): Patterns of recurrence and post-hoc survival analysis of a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 1273–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, S.M.; Powell, M.E.; Mileshkin, L.; Katsaros, D.; Bessette, P.; Haie-Meder, C.; Ottevanger, P.B.; Ledermann, J.A.; Khaw, P.; D’Amico, R.; et al. Toxicity and quality of life after adjuvant chemoradiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone for women with high-risk endometrial cancer (PORTEC-3): An open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 1114–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RAINBO Research Consortium. Refining adjuvant treatment in endometrial cancer based on molecular features: The RAINBO clinical trial program. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2022, 33, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surveillance Research Program National Cancer Institute. SEER*Explorer: An Interactive Website for SEER Cancer Statistics; National Cancer Institute: Rockville, MD, USA, 2024. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/statistics-network/explorer/ (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Marnitz, S.; Waltar, T.; Köhler, C.; Mustea, A.; Schömig-Markiefka, B. The brave new world of endometrial cancer: Future implications for adjuvant treatment decisions. Strahlenther. Und Onkol. 2020, 196, 963–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spence, R.; Turner, J.; DaSilva, W.; Driscoll, E.; Preston, M.; Tran, K.; Lui, N.; Yeoh, H.; Kaur, D.; Alsop, K.; et al. Development of an endometrial cancer survivorship checklist: Umbrella review and expert input. Asia-Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 20, 262. [Google Scholar]

| Category | Outcome | Measurement Instruments |

|---|---|---|

| Physical health outcomes | ||

| Abdominal discomfort [20,22,23,24] | EORTC-QLQ-C30; SF-36 | |

| Cachexia [25] | Weight loss; BMI; Biochemical abnormalities | |

| Fatigue [6,26,27,28,29] | BFI; EORTC-QLQ-C30; FACIT; FACIT-F; FAS; QLACS [fatigue domain]; SF-36 | |

| Lymphoedema [30,31,32] | CaSUN; Circumferential measurements; GCLQ-K; MRI; Ultrasound; Validated lymphoedema questionnaire | |

| Obesity [19,21,26,33,34,35,36] | BMI | |

| Pain [6,24,26,28,37,38] | BPI; EORTC-QLQ-C30; Numerical rating scale (0–10); Perioperative clinical data; QLACS; SF-36 | |

| Pelvic floor function [23,35,39] | APFQ; Motor evoked potential of sacral nerve; PFDI; PFM strength on digital palpation; PISQ-12 | |

| Sarcopenia [40] | Average muscle radiation attenuation; Muscle mass measurement; Skeletal muscle index | |

| Sexual function [6,22,23,26,35,37,39,41] | ACOG Sexual Dysfunction Checklist; CALGB Sexual Functioning; FSFI; PROMIS; SAQ | |

| Sleep [6,26] | Actigraphy wristwatch + sleep log; EORTC-QLQ-C30; PSQI | |

| Urinary function [22,23] | APFQ; IIQ-SF; ISI; QUID; UDI-SF | |

| Fertility-related outcomes | ||

| Gravidity [18,19,20,21,33,34,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53] | Pregnancy rates | |

| Parity [18,20,21,33,34,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,51,52,53,54,55] | Live birth rates | |

| Quality of life | ||

| Global quality of life [22,23,24,26,30,56,57] | EORTC-QLQ-C30; EORTC-QLQ-EN24; EQ-5D; FACT; FACT-En; FACT-G; Kupperman index; QOL-CS; QoR-40; RAND-36; RI10; SF-36; WHOQOL-BREF | |

| Cognition [6] | ||

| Emotional wellbeing [56,57] | ||

| Functional wellbeing [22] | ||

| Physical wellbeing [22,26,30,56] | ||

| Role functioning [22] | ||

| Sexual wellbeing [22,23,35,41,57] | ||

| Social wellbeing [22,56,57] | ||

| Treatment-related toxicities | ||

| Treatment-related toxicities [20,22,27,28,29,58] | CTCAE; EORTC; FACIT; LENT-SOMA; RTOG/EORTC late scoring scheme | |

| Mental health outcomes | ||

| Anxiety [6,26] | BDI; HADS; IDAS; PSS; SF-36; SIGH-AD | |

| Depression [6,26] | BDI; HADS; IDAS; SF-36; SIGH-AD | |

| Distress/stress [6] | BSI-18; QLACS | |

| Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Country of health care provision | ||

| Australia | 31 | (83.7) |

| New Zealand | 6 | (16.2) |

| Type of healthcare professional | ||

| Medical oncologist | 12 | (32.4) |

| Gynaecological oncologist | 11 | (29.7) |

| Oncology nurse | 8 | (21.6) |

| Nurse | 3 | (8.1) |

| Radiation oncologist | 1 | (2.7) |

| Psychologist | 1 | (2.7) |

| Oncology research clinical trials | 1 | (2.7) |

| Years of clinical experience | ||

| Graduated < 10 years ago | 9 | (24.3) |

| Graduated 10+ years ago | 26 | (70.3) |

| Missing | 2 | (5.4) |

| median | (minimum, maximum) | |

| Number of years working with endometrial cancer patients | 11.0 | (2, 28) |

| Approximate number of endometrial cancer patients seen per month | 5.0 | (<1, 30) |

| Outcome | Relevant, % |

|---|---|

| Physical health outcomes | |

| Abdominal discomfort | 78.4 |

| Body weight/obesity | 100.0 |

| Cachexia | 29.7 |

| Fatigue | 97.3 |

| Lymphoedema | 73.0 |

| Pain | 83.8 |

| Pelvic floor function | 89.2 |

| Sarcopenia | 48.6 |

| Sexual function | 89.2 |

| Sleep quality | 91.9 |

| Urinary function | 83.8 |

| Fertility-related outcomes | |

| Live birth rate (parity) | 40.5 |

| Pregnancy rate (gravidity) | 40.5 |

| Quality of life | |

| Cognitive wellbeing | 83.8 |

| Emotional wellbeing | 97.3 |

| Functional wellbeing | 100.0 |

| Physical wellbeing | 97.3 |

| Sexual wellbeing | 97.3 |

| Social wellbeing | 94.6 |

| Role functioning a | - |

| Treatment-related toxicities | |

| Treatment-related toxicities | 78.4 |

| Mental health outcomes | |

| Anxiety | 94.6 |

| Cognition | 75.7 |

| Depression | 94.6 |

| Distress/Stress a | - |

| Sexual wellbeing Dilator use Sexual function vs. libido Mental health, psychological and emotional outcomes Fear of recurrence Interpersonal relationships particularly partner relationship Social support Loneliness Physical health outcomes Cardiovascular function/general fitness/physical fitness Weight loss Treatment-related toxicities and health outcomes Immune adverse event survivorship Bone health and pelvic insufficiency fractures Scarring/surgical scar tissue Risk of toxicity (premature) Menopause management 1 Complementary and alternative treatments 2 Work and financial outcomes Financial toxicity Returning to work Return to usual activities Ability to continue to undertake caring roles Changes to identity/roles and life values/goals Preservation of independence Surveillance and recurrence Risk of recurrence Imaging surveillance Treatment options for recurrence Communication and access to information Unmet information needs by patient Unmet information needs by family Peer advocacy Role of immunotherapy Complementary and alternative treatments 2 Other Failure of radiation Living with late stage/metastatic disease |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

DiSipio, T.; Turner, J.; Da Silva, W.; Driscoll, E.; Preston, M.; Tran, K.; Varnier-Lui, N.; Yeoh, H.-L.; Kaur, D.; Alsop, K.; et al. Understanding Contemporary Endometrial Cancer Survivorship Issues: Umbrella Review and Healthcare Professional Survey. Cancers 2025, 17, 2696. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17162696

DiSipio T, Turner J, Da Silva W, Driscoll E, Preston M, Tran K, Varnier-Lui N, Yeoh H-L, Kaur D, Alsop K, et al. Understanding Contemporary Endometrial Cancer Survivorship Issues: Umbrella Review and Healthcare Professional Survey. Cancers. 2025; 17(16):2696. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17162696

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiSipio, Tracey, Jemma Turner, William Da Silva, Elizabeth Driscoll, Marta Preston, Krystel Tran, Nicla Varnier-Lui, Hui-Ling Yeoh, Dayajyot Kaur, Kathryn Alsop, and et al. 2025. "Understanding Contemporary Endometrial Cancer Survivorship Issues: Umbrella Review and Healthcare Professional Survey" Cancers 17, no. 16: 2696. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17162696

APA StyleDiSipio, T., Turner, J., Da Silva, W., Driscoll, E., Preston, M., Tran, K., Varnier-Lui, N., Yeoh, H.-L., Kaur, D., Alsop, K., Hayes, S. C., Janda, M., & Spence, R. R. (2025). Understanding Contemporary Endometrial Cancer Survivorship Issues: Umbrella Review and Healthcare Professional Survey. Cancers, 17(16), 2696. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17162696