Real Life Evolution of Surgical Approaches in the Management of Endometrial Cancer in Poland

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistics

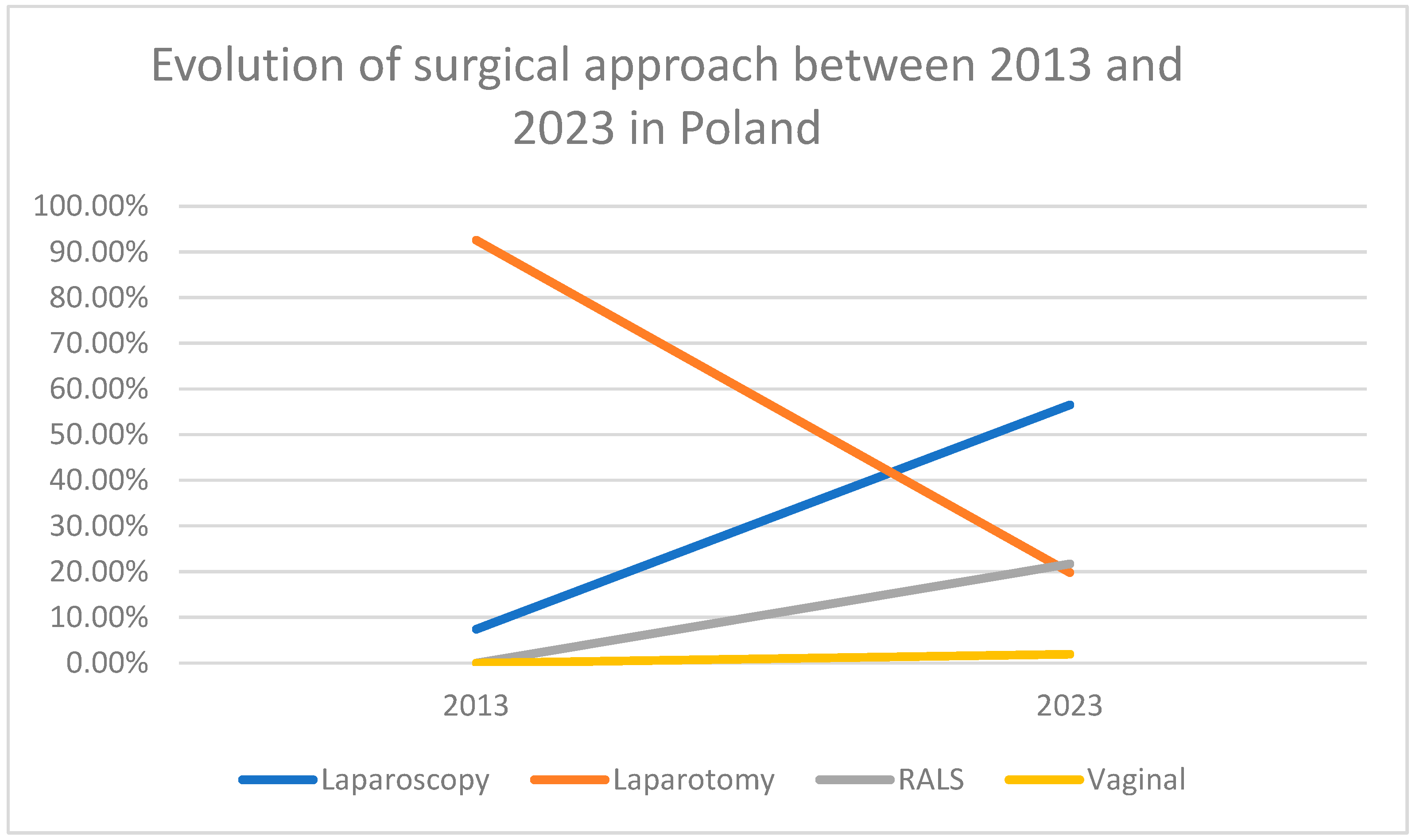

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings—Shift to Minimally Invasive Surgery

4.2. Rate of Conversions

4.3. Impact of RALS

4.4. Impact of Obesity

4.5. Strength and Weaknesses of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EC | Endometrial cancer |

| RALS | Robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery |

| LPS | Conventional laparoscopy |

| MIS | Minimally invasive surgery |

| ESGO | European Society of Gynecologic Oncology |

| ESMO | European Society of Medical Oncology |

| FIGO | International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| SD | Standard deviation |

References

- Strona Główna|Krajowy Rejestr Nowotworów [Internet]. Raporty | Krajowy Rejestr Nowotworów. Available online: https://onkologia.org.pl/pl/raporty (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Walker, J.L.; Piedmonte, M.R.; Spirtos, N.M.; Eisenkop, S.M.; Schlaerth, J.B.; Mannel, R.S.; Spiegel, G.; Barakat, R.; Pearl, M.L.; Sharma, S.K. Laparoscopy compared with laparotomy for comprehensive surgical staging of uterine cancer: Gynecologic Oncology Group Study LAP2. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 5331–5336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janda, M.; Gebski, V.; Davies, L.C.; Forder, P.; Brand, A.; Hogg, R.; Jobling, T.W.; Land, R.; Manolitsas, T.; Nascimento, M.; et al. Effect of Total Laparoscopic Hysterectomy vs Total Abdominal Hysterectomy on Disease-Free Survival Among Women With Stage I Endometrial Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2017, 317, 1224–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourits, M.J.; Bijen, C.B.; Arts, H.J.; ter Brugge, H.G.; van der Sijde, R.; Paulsen, L.; Wijma, J.; Bongers, M.Y.; Post, W.J.; van der Zee, A.G.; et al. Safety of laparoscopy versus laparotomy in early-stage endometrial cancer: A randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010, 11, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Concin, N.; Matias-Guiu, X.; Vergote, I.; Cibula, D.; Mirza, M.R.; Marnitz, S.; Ledermann, J.; Bosse, T.; Chargari, C.; Fagotti, A.; et al. ESGO/ESTRO/ESP guidelines for the management of patients with endometrial carcinoma. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2021, 31, 12–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oaknin, A.; Bosse, T.J.; Creutzberg, C.L.; Giornelli, G.; Harter, P.; Joly, F.; Lorusso, D.; Marth, C.; Makker, V.; Mirza, M.R.; et al. Endometrial cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annal. Oncol. 2022, 33, 860–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Concin, N.; Planchamp, F.; Abu-Rustum, N.R.; Ataseven, B.; Cibula, D.; Fagotti, A.; Fotopoulou, C.; Knapp, P.; Marth, C.; Morice, P.; et al. European Society of Gynaecological Oncology quality indicators for the surgical treatment of endometrial carcinoma. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2021, 31, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdrowe Dane-ezdrowie.gov.pl. Available online: https://ezdrowie.gov.pl/portal/home/badania-i-dane/zdrowe-dane (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Zullo, F.; Palomba, S.; Russo, T.; Falbo, A.; Costantino, M.; Tolino, A.; Zupi, E.; Tagliaferri, P.; Venuta, S. A Prospective Randomized Comparison between Laparoscopic and Laparotomic Approaches in Women with Early Stage Endometrial Cancer: A Focus on the Quality of Life. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 193, 1344–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janda, M.; Gebski, V.; Brand, A.; Hogg, R.; Jobling, T.W.; Land, R.; Manolitsas, T.; McCartney, A.; Nascimento, M.; Neesham, D.; et al. Quality of Life after Total Laparoscopic Hysterectomy versus Total Abdominal Hysterectomy for Stage I Endometrial Cancer (LACE): A Randomised Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010, 11, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomba, S.; Ghezzi, F.; Falbo, A.; Mandato, V.D.; Annunziata, G.; Lucia, E.; Cromi, A.; Zannoni, L.; Seracchioli, R.; Giorda, G.; et al. Conversion in endometrial cancer patients scheduled for laparoscopic staging: A large multicenter analysis: Conversions and endometrial cancer. Surg. Endosc. 2014, 28, 3200–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.S.; Mowers, E.L.; Mahnert, N.; Skinner, B.D.; Kamdar, N.; Morgan, D.M.; As-Sanie, S. Risk Factors and Outcomes for Conversion to Laparotomy of Laparoscopic Hysterectomy in Benign Gynecology. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 128, 1295–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, K.; Jung, C.E.; Hom, M.S.; Gualtieri, M.R.; Randazzo, S.C.; Kanao, H.; Yessaian, A.A.; Roman, L.D. Predictive Factor of Conversion to Laparotomy in Minimally Invasive Surgical Staging for Endometrial Cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2016, 26, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrie, T.A.; Liu, H.; Lu, D.; Dowswell, T.; Song, H.; Wang, L.; Shi, G. Robot-assisted surgery in gynaecology. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 4, CD011422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäenpää, M.M.; Nieminen, K.; Tomás, E.I.; Laurila, M.; Luukkaala, T.H.; Mäenpää, J.U. Robotic-assisted vs traditional laparoscopic surgery for endometrial cancer: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 215, 588.e1–588.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinoi, G.; Tarantino, V.; Bizzarri, N.; Perrone, E.; Capasso, I.; Giannarelli, D.; Querleu, D.; Giuliano, M.C.; Fagotti, A.; Scambia, G.; et al. Robotic-assisted versus conventional laparoscopic surgery in the management of obese patients with early endometrial cancer in the sentinel lymph node era: A randomized controlled study (RObese). Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2024, 34, 773–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronsini, C.; Fordellone, M.; Braca, E.; Di Donna, M.C.; Solazzo, M.C.; Cucinella, G.; Scaffa, C.; De Franciscis, P.; Chiantera, V. Safety and Efficacy Outcomes of Robotic, Laparoscopic, and Laparotomic Surgery in Severe Obese Endometrial Cancer Patients: A Network Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2025, 17, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.H.; Dagher, C.; Abu-Rustum, N.R.; Mueller, J.J.; Sonoda, Y.; Zivanovic, O.; Broach, V.; Leitao, M.M., Jr. Oncologic outcomes of robot-assisted laparoscopy versus conventional laparoscopy for the treatment of apparent early-stage endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the uterus. Gynecol Oncol. 2023, 179, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delso, V.; Hoyo, R.S.; Sánchez-Barderas, L.; Gracia, M.; Baquedano, L.; Martínez-Maestre, M.A.; Fasero, M.; Coronado, P.J. Survival Impact of Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopy (RAL) vs. Conventional Laparoscopy (LPS) in the Treatment of Endometrial Cancer. Cancers 2025, 17, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narducci, F.; Bogart, E.; Hebert, T.; Gauthier, T.; Collinet, P.; Classe, J.M.; Lecuru, F.; Delest, A.; Motton, S.; Conri, V.; et al. Severe perioperative morbidity after robot-assisted versus conventional laparoscopy in gynecologic oncology: Results of the randomized ROBOGYN-1004 trial. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020, 158, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coronado, P.J.; Herraiz, M.A.; Magrina, J.F.; Fasero, M.; Vidart, J.A. Comparison of Perioperative Outcomes and Cost of Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopy, Laparoscopy and Laparotomy for Endometrial Cancer. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2012, 165, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coronado, P.J.; Gracia, M.; Ramirez Mena, M.; Bellon del Amo, M.; Garcia-Santos, J.; Fasero Laiz, M. The Well-Being of the Gynecological Surgeon Improves with the Robot-Assisted Surgery. Anales RANM 2023, 139, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, G.; Vizza, E.; Cela, V.; Mereu, L.; Bogliolo, S.; Legge, F.; Ciccarone, F.; Mancini, E.; Gallotta, V.; Baiocco, E.; et al. Laparoscopic versus Robotic Hysterectomy in Obese and Extremely Obese Patients with Endometrial Cancer: A Multi-Institutional Analysis. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 44, 1935–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, P.C.; Kang, E.; Park, D.H. Learning curve and surgical outcome for robotic-assisted hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy: Case-matched controlled comparison with laparoscopy and laparotomy for treatment of endometrial cancer. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2010, 17, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, L.; Satava, R.M.; Pellegrini, C.A.; Sinanan, M.N. Robotic surgery: Identifying the learning curve through objective measurement of skill. Surg. Endosc. 2003, 17, 1744–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yohannes, P.; Rotariu, P.; Pinto, P. Comparison of robotic versus laparoscopic skills: Is there a difference in the learning curve? Urology 2002, 60, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gracia, M.; García-Santos, J.; Ramirez, M.; Bellón, M.; Herraiz, M.A.; Coronado, P.J. Value of Robotic Surgery in Endometrial Cancer by Body Mass Index. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 150, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusimano, M.C.; Simpson, A.N.; Dossa, F.; Liani, V.; Kaur, Y.; Acuna, S.A.; Robertson, D.; Satkunaratnam, A.; Bernardini, M.Q.; Ferguson, S.E.; et al. Laparoscopic and robotic hysterectomy in endometrial cancer patients with obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis of conversions and complications. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 221, 410–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditto, A.; Chiarello, G.; Leone Roberti Maggiore, U.; Martinelli, F.; Bogani, G.; Raspagliesi, F. Low-pressure laparoscopic procedure in morbidly obese patients with endometrial carcinoma using a new subcutaneous abdominal wall-retraction device: A surgical challenge. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2023, 33, 1974–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 2013 N = 417 | 2023 N = 640 | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 63.7 ± 10.5 | 65.2 ± 10.3 | 0.027 | |

| BMI (mean ± SD) | 31.4 ± 7.1 | 31.2 ± 7.1 | 0.712 | |

| Previous laparotomy | 109 (26.1%) | 192 (30%) | 0.007 | |

| FIGO 2009 preoperative stage | 0.013 | |||

| IA | 221 (53%) | 370 (57.8%) | 0.139 | |

| IB | 110 (26.4%) | 192 (30%) | 0.229 | |

| II | 20 (4.8%) | 67 (10.5%) | 0.002 | |

| NA | 66 (15.8%) | 11 (1.7%) | <0.001 | |

| FIGO 2009 postoperative stage | 0.608 | |||

| IA | 135 (32.3%) | 329 (51.4%) | <0.001 | |

| IB | 64 (15.3%) | 150 (23.4%) | 0.002 | |

| II | 46 (11.1%) | 85 (13.3%) | 0.322 | |

| IIIA | 6 (1.4%) | 10 (1.6%) | 0.999 | |

| IIIB | 9 (2.2%) | 18 (2.8%) | 0.646 | |

| IIIC | 20 (4.8%) | 44 (6.9%) | 0.210 | |

| IV | 2 (0.5%) | 4 (0.6%) | 0.999 | |

| NA | 135 (32.4%) | 0 (0%) | <0.001 | |

| Intraoperative complications | 16 (3.8%) | 25 (3.9%) | 0.990 | |

| Postoperative complications | 52 (12.5%) | 31 (4.8%) | <0.001 |

| SURGICAL APPROACH | 2013 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|

| Laparoscopy | 31 (7.4%) | 362 (56.5%) |

| Robot-assisted surgery | - | 139 (21.7%) |

| Laparotomy | 386 (92.6%) | 127 (19.8%) |

| Vaginal | - | 12 (1.9%) |

| Total | 417 | 640 |

| POSTOPERATIVE COMPLICATIONS | 2013 N (%) | 2023 N (%) | p Value | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bleeding | 7 (1.7%) | 4 (0.6%) | 0.367 | 1.8 (0.5–5.9) |

| Urinary tract injury | 4 (1%) | 1 (0.2%) | 0.179 | 4.0 (0.4–35.8) |

| Bowel injury | 1 (0.2%) | 3 (0.5%) | 0.317 | 0.3 (0.03–3.2) |

| Infections | 36 (8.6%) | 12 (1.9%) | <0.001 | 3.0 (1.6–5.7) |

| Other | 4 (1%) | 11 (1.7%) | 0.071 | 0.4 (0.1–1.1) |

| Total | 52 (12.5%) | 31 (4.8%) | <0.001 | 0.60 (0.50–0.72) |

| CONVERSIONS ACCORDING TO SURGICAL APPROACH in 2023 N = 22 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Total MIS | 22/513 | 4.3% |

| Laparoscopy | 21/362 | 5.8% |

| Vaginal | 1/12 | 8.3% |

| Robot-assisted surgery | 0/139 | 0% |

| REASON OF CONVERSION | ||

|---|---|---|

| Bleeding | 7 | 28.0 % |

| Peritoneal spread | 1 | 4.0 % |

| Urinary/bowel complications | 2 | 8.0 % |

| Anesthesiological reason | 1 | 4.0 % |

| Suboptimal exposition | 5 | 20.0 % |

| Adhesions | 9 | 36.0 % |

| Total | 22 | |

| CONVERSION GROUP (N = 22) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 66.5 ± 10.9 | |

| BMI (mean ± SD) | 32.6 ± 6.1 | |

| Previous laparotomy | 9 (40.9%) | |

| FIGO 2009 preoperative stage | ||

| IA | 13 (59.1%) | |

| IB | 7 (31.9%) | |

| II | 2 (9%) | |

| FIGO 2009 postoperative stage | ||

| IA | 9 (40.9%) | |

| IB | 6 (27.2%) | |

| II | 4 (18.2%) | |

| IIIA | 1 (4.5%) | |

| IIIB | 0 | |

| IIIC | 2 (9.1%) | |

| Intraoperative complications | 5 (22.7%) | |

| Postoperative complications | 2 (9.1%) | |

| RALS (n = 139) | LPS (n = 362) | p Value | OR (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 63.9 ± 9.1 | 65.7 ± 10.5 | 0.733 | - |

| BMI (mean ± SD) | 32.1 ± 6.1 | 31.5 ± 6.8 | 0.329 | - |

| Conversions | 0 (0%) | 21 (5.8%) | 0.016 | - |

| Previous laparotomy | 31 (22.3%) | 97 (26.7%) | <0.001 | 15.6 (2.9–83.4) |

| Intraoperative complications | 1 (0.7%) | 9 (2.4%) | 0.693 | 0.5 (0.1–2.9) |

| Postoperative complications | 0 (0%) | 19 (5.2%) | 0.026 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rychlik, A.; Kluz, T.; Szewczyk, G.; Coronado, P.J.; Łatkiewicz, T.; Tarkowski, R.; Woińska-Przekwas, A.; Nowosielski, K.; Skowronek, K.; Stojko, R.; et al. Real Life Evolution of Surgical Approaches in the Management of Endometrial Cancer in Poland. Cancers 2025, 17, 2626. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17162626

Rychlik A, Kluz T, Szewczyk G, Coronado PJ, Łatkiewicz T, Tarkowski R, Woińska-Przekwas A, Nowosielski K, Skowronek K, Stojko R, et al. Real Life Evolution of Surgical Approaches in the Management of Endometrial Cancer in Poland. Cancers. 2025; 17(16):2626. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17162626

Chicago/Turabian StyleRychlik, Agnieszka, Tomasz Kluz, Grzegorz Szewczyk, Pluvio J. Coronado, Tomasz Łatkiewicz, Rafał Tarkowski, Anna Woińska-Przekwas, Krzysztof Nowosielski, Kaja Skowronek, Rafał Stojko, and et al. 2025. "Real Life Evolution of Surgical Approaches in the Management of Endometrial Cancer in Poland" Cancers 17, no. 16: 2626. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17162626

APA StyleRychlik, A., Kluz, T., Szewczyk, G., Coronado, P. J., Łatkiewicz, T., Tarkowski, R., Woińska-Przekwas, A., Nowosielski, K., Skowronek, K., Stojko, R., Skuza, M., Misiek, M., Jabłoński, K., Sadłecki, P., Ciosek, M., Pasicz, K., Bogaczyk, A., & Bidziński, M. (2025). Real Life Evolution of Surgical Approaches in the Management of Endometrial Cancer in Poland. Cancers, 17(16), 2626. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17162626