Advances in Surgical Management of Malignant Gastric Outlet Obstruction

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Definition of Gastric Outlet Obstruction (GOO)

1.2. Epidemiology

1.3. Etiology Shift

1.4. Evidence Grading

2. Etiology of Gastric Outlet Obstruction

2.1. Malignant Causes

2.2. Benign Causes

3. Clinical Manifestations

- •

- Epigastric Pain

- •

- Nausea and VomitingNausea and vomiting, particularly postprandial vomiting, are hallmark features of GOO [6,20]. Accumulated gastric contents cannot pass through the obstructed pylorus or duodenum, leading to retching and eventual vomiting of undigested food [7]. These symptoms can be especially distressing and may progressively worse if the obstruction persists [7,20].

- •

- Early Satiety

- •

- Abdominal DistensionChronic accumulation of gastric contents and gas contributes to visible abdominal distension or bloating. Physical examination may reveal a percussion splash, reflecting significant fluid retention within the stomach. Such findings underscore the mechanical nature of GOO and help differentiate it from functional dyspepsia [22,23,24].

- •

- Weight LossInadequate oral intake, combined with persistent vomiting, often leads to weight loss and compromised nutritional status. This issue is especially pronounced in malignant GOO, where advanced tumor burden may further diminish appetite. Early nutritional interventions—such as parenteral or enteral feeding—can be critical to maintaining the patient’s overall condition [25].

4. Diagnosis

4.1. History & Physical Examination

- (1)

- Symptom Assessment

- (2)

- Nutritional Status and HydrationChronic vomiting and inadequate oral intake often result in electrolyte imbalances and malnutrition. Clinicians should evaluate weight changes, muscle wasting, and signs of dehydration [26].

- (3)

- Physical ExaminationOn physical exam, a “succussion splash,” a sloshing sound heard during abdominal movement, may be detected in the epigastrium, suggesting fluid retention within a distended stomach [7,20]. Abdominal distension or tenderness could further point to possible tumor masses or secondary complications like peritonitis [27].

4.2. Endoscopic Evaluation

- -

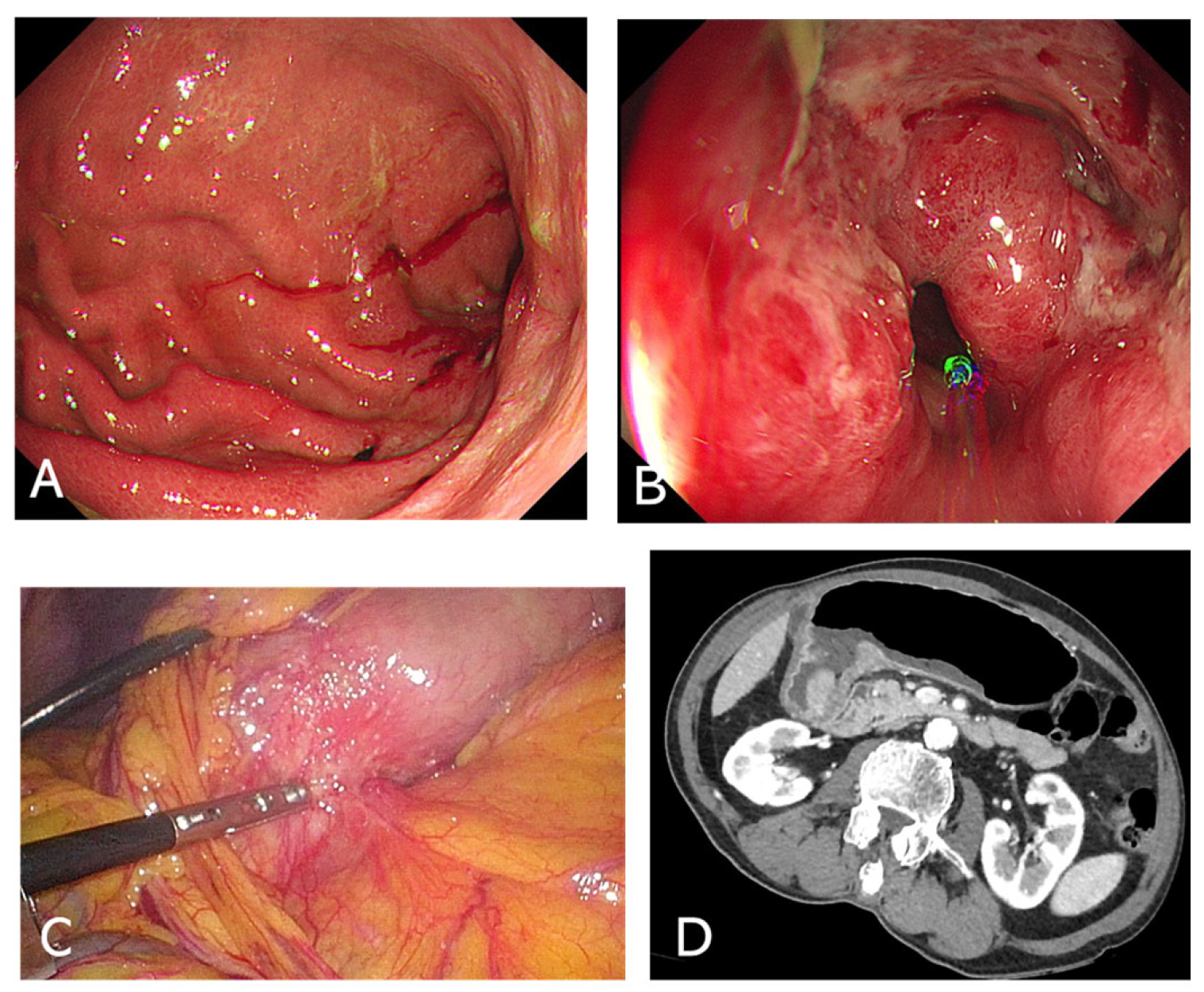

- Upper Endoscopy (EGD)Endoscopic examination is vital for direct visualization of the gastric outlet and duodenum (Figure 1A,B). It confirms the presence of an obstructing lesion and enables biopsy for histopathological analysis, distinguishing between benign and malignant etiologies. In many cases, EGD also offers therapeutic potential, such as stent placement [28].

- -

- Differential DiagnosisEndoscopic findings help rule out peptic ulcer–related strictures, malignancies like gastric cancer or lymphoma, or more unusual causes such as impacted bezoars. If malignancy is suspected, obtaining multiple biopsies from the lesion edge and surrounding mucosa can improve diagnostic accuracy [29].

4.3. Imaging Studies

- -

- CT Scan

- -

- Additional Imaging Considerations

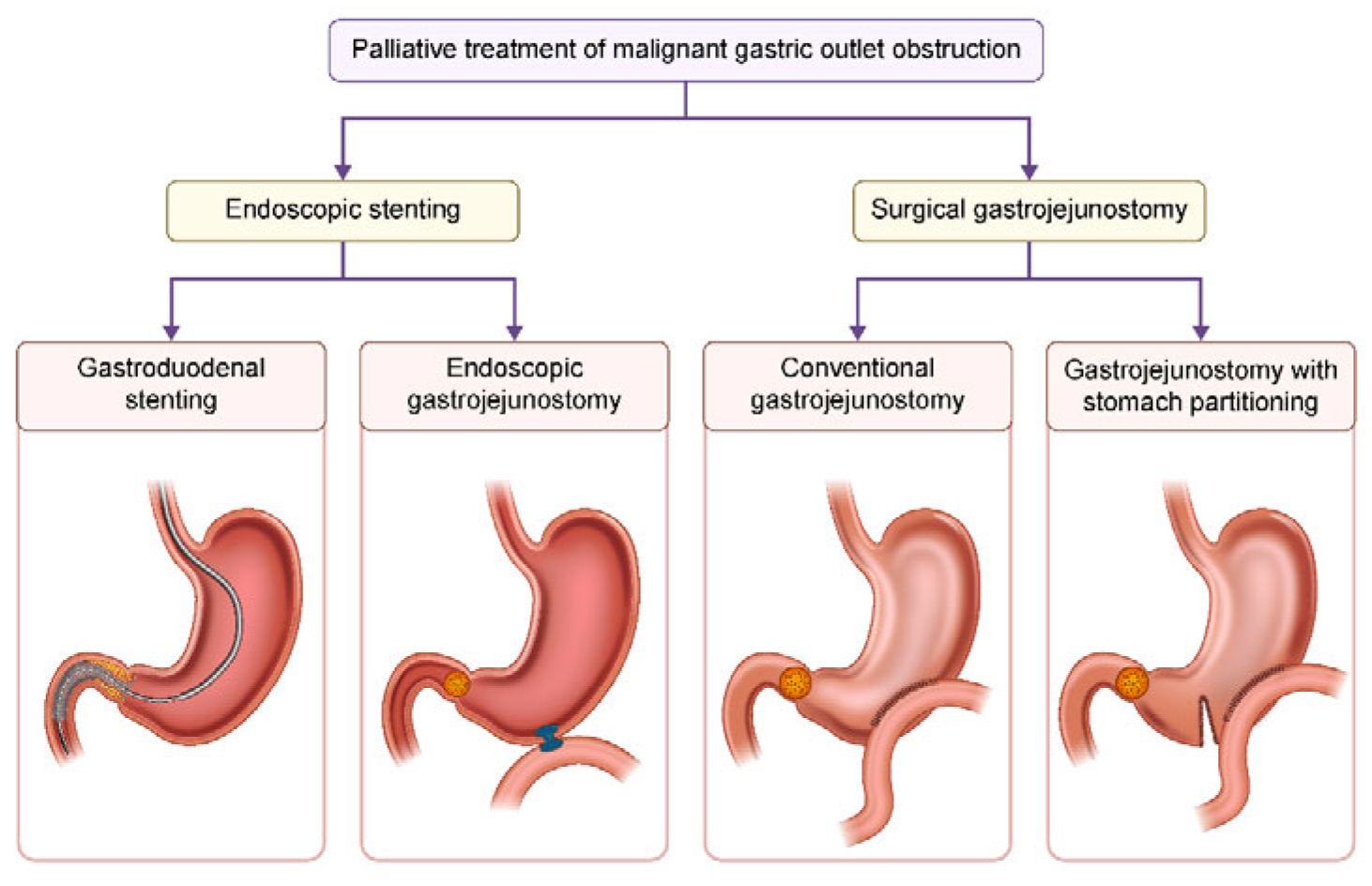

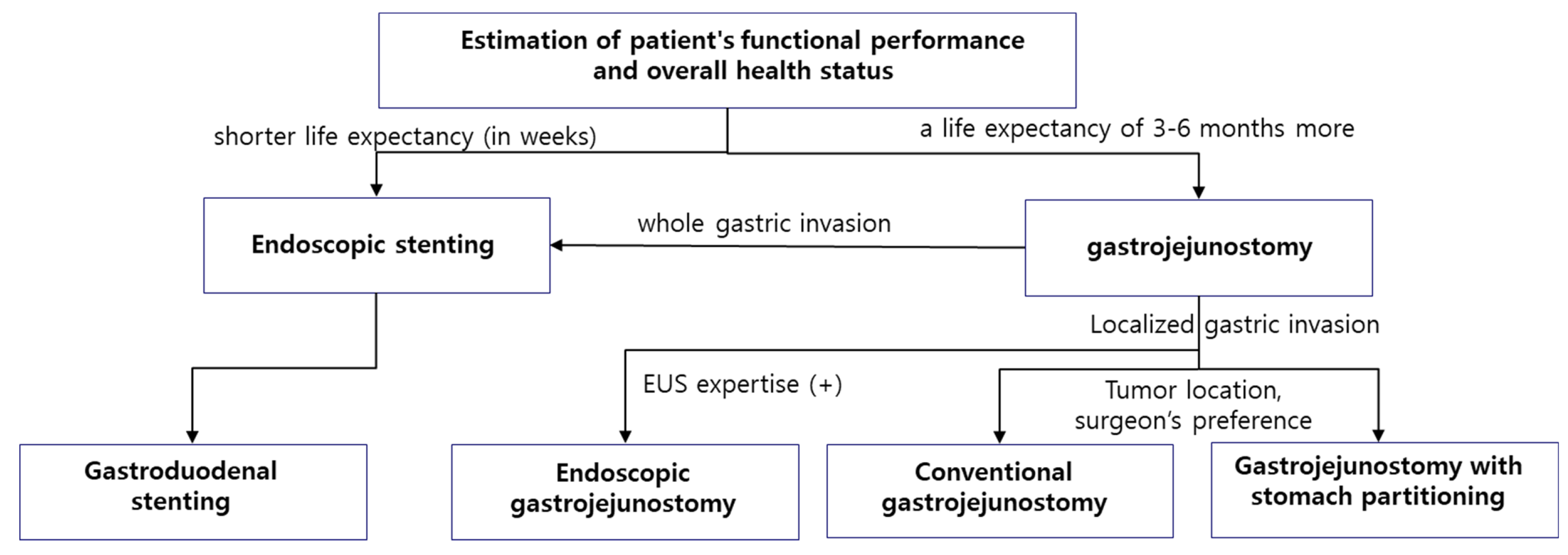

5. Treatment Strategies for Malignant GOO (Figure 2)

5.1. Conservative Management [5]

- •

- Intravenous fluid administration and correction of electrolyte imbalances

- •

- Maintaining nil per os (NPO) status

- •

- Administration of high-dose proton pump inhibitors to reduce gastric secretions

- •

- Nasogastric tube insertion when necessary

- •

- Evidence Quality: Low to moderate—these recommendations are largely supported by clinical consensus and observational studies rather than randomized controlled trials (RCTs). They represent standard supportive care derived from physiological rationale and clinical experience.

- •

- Grading: Grade C (based on observational data and expert opinion). Essential but not directly evidence-proven interventions.

5.2. Endoscopic Stenting [33]

- •

- •

- Higher risk of re-obstruction due to tumor ingrowth, potentially requiring repeat procedures.

- •

- Suitable for patients with shorter life expectancy.

- •

- Evidence Quality: Moderate—based mostly on observational cohort studies and some comparative analyses; a few prospective studies but limited RCT evidence. Benefits in symptom palliation are consistently reported though long-term patency and reintervention rates vary.

- •

- Grading: Grade B (moderate quality observational evidence). Well-supported for palliation but with known limitations.

- •

- Patient Selection Criteria:

- •

- Inclusion:

- -

- Patients with unresectable malignant gastric outlet obstruction requiring palliation.

- -

- Poor surgical candidates due to comorbidities or limited life expectancy (generally <3–6 months).

- -

- Patients needing rapid symptom control with minimal invasiveness.

- •

- Exclusion:

- -

- Patients with extensive tumor infiltration precluding safe stent deployment.

- -

- Those with high risk of stent-related complications or expected survival longer than 6 months where durable surgical options may be preferable.

- •

- Long-term Outcomes

- -

- -

- •

- Survival

- •

- Quality of Life

- -

- Symptom palliation is rapid and marked by improved ability to tolerate oral intake. However, repeated interventions due to obstruction limits sustained gains in quality of life.

5.3. Conventional Surgical Gastrojejunostomy [38]

- •

- Traditional standard treatment offering long-term symptom relief.

- •

- Higher risk of postoperative complications and longer hospital stays.

- •

- Recommended for operable patients with a life expectancy of 3–6 months or more.

- •

- Evidence Quality: Moderate—supported by retrospective case series and some prospective observational studies comparing outcomes with stenting. RCTs are limited due to ethical/practical concerns.

- •

- Grading: Grade B (moderate observational evidence). Long-term outcome benefit acknowledged; perioperative risks well characterized.

- •

- Patient Selection Criteria:

- •

- Inclusion:

- -

- Patients who are operable with acceptable performance status (e.g., ECOG 0–2).

- -

- Life expectancy ≥3–6 months where longer-lasting symptom relief justifies surgery risk.

- •

- Exclusion:

- -

- Patients with prohibitive surgical risk due to comorbidities or poor performance status.

- -

- Very limited life expectancy (<3 months) where surgical morbidity outweighs benefit.

- •

- Long-term Outcomes

- •

- Survival

- •

- Quality of Life

5.4. Stomach Partitioning Gastrojejunostomy (SPGJ) [41]

- •

- SPGJ is a surgical technique developed to address the limitations of conventional gastrojejunostomy.

- •

- It partially divides the stomach, allowing food to be directly evacuated into the jejunum.

- •

- It reduces the incidence of delayed gastric emptying (DGE).

- •

- It decreases the risk of tumor-related bleeding.

- •

- Technical detail

- -

- The SPGJ technique involves partial division of the stomach at the junction of the gastric body and antrum, or approximately 5 cm proximal to the upper margin of the tumor, using a linear stapler. This maneuver preserves a narrow 2–3 cm strip of gastric corpus adjacent to the lesser curvature, ensuring vascular continuity and physiologic drainage of gastric secretions. An enterotomy is then made at the greater curvature of the proximal stomach, and a corresponding opening is created on the mesenteric border of the jejunum, situated 5–10 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz. The jejunal limb is subsequently brought to the gastric anastomotic site posterior to the transverse colon, and a side-to-side gastrojejunostomy is fashioned using a linear stapler. The common enterotomy is closed by continuous, barbed suture, completing the anastomosis [34].

- •

- Advantages of SPGJ:

- ➀

- Faster recovery of oral intake compared to conventional gastrojejunostomy

- ➁

- More complete diet possible after 15 days

- ➂

- Reduced incidence of DGE

- ➃

- Decreased need for reoperation

- ➄

- Potential for improved overall survival rates

- •

- Evidence Quality: Low to moderate—mostly from small cohort studies, retrospective analyses, and single-center experiences; comparative data limited and lacking large RCTs.

- •

- Grading: Grade C to B (primarily observational studies). Promising but requires further well-designed studies to confirm benefits and generalizability.

- •

- Patient Selection Criteria:

- •

- Inclusion:

- -

- Patients with good functional status (e.g., ECOG 0–1) and operable tumor burden.

- -

- Expected survival longer than 3–6 months to benefit from improved nutritional recovery.

- -

- Cases where EUS-GE is not available or contraindicated.

- •

- Exclusion:

- -

- Patients with poor performance status or significant comorbidities precluding surgery.

- -

- Advanced tumor invasion limiting feasibility of stomach partitioning.

- •

- Long-term Outcomes

- •

- Survival

- •

- Quality of Life

- -

- SPGJ provides a better and faster return to normal diet, which may translate to improved quality of life in the early and medium term [43].

5.5. EUS-Guided Gastroenterostomy [44]

- •

- A novel technique combining the advantages of surgery and endoscopy.

- •

- Minimally invasive with potential for long-term efficacy.

- •

- Not yet standardized and requires further research.

- •

- Evidence Quality: Low—mainly early-phase studies, pilot cohorts, and case series. Lack of standardization and robust comparative data.

- •

- Grading: Grade C (low-quality evidence). Promising but investigational; further rigorous trials needed.

- •

- Patient Selection Criteria:

- •

- Inclusion:

- -

- Patients deemed high-risk for conventional surgery but with longer expected survival than palliation candidates.

- -

- Those in centers with experienced endoscopists and availability of specialized equipment.

- -

- Patients unsuitable for stenting due to anatomical factors or prior stent failure.

- •

- Exclusion:

- -

- Patients in resource-limited settings without access to advanced endoscopic modalities.

- -

- Unfit patients who cannot tolerate longer procedural times or potential complications.

- -

- Lack of institutional expertise.

- •

- Long-term Outcomes

- •

- Survival

- •

- Quality of Life

5.6. Comparative Features of GJ, SPGJ, and EUS-GE [48,49,50,51,52,53]

- •

- Evidence Quality: Low to moderate—based on pooled observational data, retrospective comparisons, and limited prospective cohorts. Direct head-to-head RCTs rare or absent.

- •

- Grading: Grade C to B. The comparative advantages described should be interpreted cautiously in light of study heterogeneity and potential biases.

6. Considerations for Treatment

6.1. Laparoscopic vs. Open Surgery

6.2. Stomach Partitioning Gastrojejunostomy (SPGJ) vs. Conventional GJ

6.3. Stomach Partitioning: Pros & Cons

7. Factors to Consider in Treatment Selection

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Troncone, E.; Fugazza, A.; Cappello, A.; Del Vecchio Blanco, G.; Monteleone, G.; Repici, A.; Teoh, A.Y.B.; Anderloni, A. Malignant gastric outlet obstruction: Which is the best therapeutic option? World J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 26, 1847–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canakis, A.; Irani, S.S. Endoscopic Treatment of Gastric Outlet Obstruction. Gastrointest. Endosc. Clin. North. Am. 2024, 34, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, B.W.; Lee, K.C.; Hou, M.C. Endoscopic management of malignant gastric outlet obstruction. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2021, 84, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, S.L.H.; Teoh, A.Y.B. Optimal Management of Gastric Outlet Obstruction in Unresectable Malignancies. Gut Liver 2022, 16, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cominardi, A.; Tamanini, G.; Brighi, N.; Fusaroli, P.; Lisotti, A. Conservative management of malignant gastric outlet obstruction syndrome-evidence based evaluation of endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastroentero-anastomosis. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2021, 13, 1086–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papanikolaou, I.S.; Siersema, P.D. Gastric Outlet Obstruction: Current Status and Future Directions. Gut Liver 2022, 16, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, S.J.; Lee, J. Management of gastric outlet obstruction: Focusing on endoscopic approach. World J. Gastrointest. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 11, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maharshi, S.; Sharma, D.; Sharma, S.S.; Sharma, K.K.; Pokharna, R.; Nijhawan, S. Aetiology and clinical spectrum of gastric outlet obstruction in North West India. Trop. Doct 2023, 53, 433–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, U.; Khara, H.S.; Hu, Y.; Kumar, V.; Tufail, K.; Confer, B.; Diehl, D.L. EUS-guided gastroenterostomy for the management of gastric outlet obstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Endosc. Ultrasound 2020, 9, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindarajan, K.K. Revisiting malignant gastric outlet obstruction: Where do we stand? World J. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2025, 17, 100472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, A.P.; Hadaya, J.E.; Sanaiha, Y.; Chervu, N.L.; Girgis, M.D.; Benharash, P. A national perspective on palliative interventions for malignant gastric outlet obstruction. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2025, 29, 101884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.L.; Lin, J.X.; Lin, G.T.; Huang, C.M.; Zheng, C.H.; Xie, J.W.; Wang, J.B.; Lu, J.; Chen, Q.Y.; Li, P. Global incidence and mortality trends of gastric cancer and predicted mortality of gastric cancer by 2035. BMC Public. Health 2024, 24, 1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, R.; Candaş, B.; Usta, M.A.; Türkyılmaz, S.; Çalık, A.; Güner, A. Efficacy of stomach-partitioning on gastric emptying in patients undergoing palliative gastrojejunostomy for malign gastric outlet obstruction. Turk. J. Trauma. Emerg. Surg. Ulus. Travma Ve Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2020, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, K.V.; Vo, N.P.; Nguyen, H.S.; Vo, N.T.; Thai, T.B.T.; Pham, V.A.; Loh, E.W.; Tam, K.W. Palliative procedures for malignant gastric outlet obstruction: A network meta-analysis. Endoscopy 2024, 56, 780–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Vist, G.E.; Kunz, R.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Schünemann, H.J. GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008, 336, 924–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.S.; Tai, W.C.; Hu, M.L.; Wu, K.L.; Chiu, Y.C. Predicting the progress of caustic injury to complicated gastric outlet obstruction and esophageal stricture, using modified endoscopic mucosal injury grading scale. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 919870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udgirkar, S.; Surude, R.; Zanwar, V.; Chandnani, S.; Contractor, Q.; Rathi, P. Gastroduodenal Tuberculosis: A Case Series and Review of Literature. Clin. Med. Insights Gastroenterol. 2018, 11, 1179552218790566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziogas, D.; Vasilakis, T.; Kapizioni, C.; Koukoulioti, E.; Tziatzios, G.; Gkolfakis, P.; Facciorusso, A.; Papanikolaou, I.S. Revealing Insights: A Comprehensive Overview of Gastric Outlet Obstruction Management, with Special Emphasis on EUS-Guided Gastroenterostomy. Med. Sci. 2024, 12, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, J.; Thomson, S.; Taylor, M.; Scoffield, J. A reminder of the classical biochemical sequelae of adult gastric outlet obstruction. BMJ Case Rep. 2011, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koop, A.H.; Palmer, W.C.; Stancampiano, F.F. Gastric outlet obstruction: A red flag, potentially manageable. Cleve Clin. J. Med. 2019, 86, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, R. Gastric Outlet Obstruction Secondary to Gastric Adenocarcinoma Diagnosed on Ultrasonography. J. Microsc. Ultrastruct. 2024, 12, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, S.; Anwar, K.; Khan, A.; Nocivelli, I.; Skolik, Z. Circumferential Pyloric Ulcer Inducing Gastric Outlet Obstruction: A Report of a Rare Case. Cureus 2024, 16, e71268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bathobakae, L.; Bashir, R.; Venero, S.; Wilkinson, T.; Yuridullah, R.; Cavanagh, Y.; Baddoura, W. Acute Gastric Dilatation: A Retrospective Case Series from a Single Institution. Case Rep. Gastroenterol. 2024, 18, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasler, W.L. Gas and Bloating. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2006, 2, 654–662. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L.; Chen, X.P. Treatment of choice for malignant gastric outlet obstruction: More than clearing the road. World J. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2024, 16, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.H.; Jung, K.W. Vomiting. Korean J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 70, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouassida, M.; Mighri, M.M.; Becha, D.; Hamzaoui, L.; Sassi, S.; Azzouz, M.M.; Touinsi, H.; Sassi, S. Huge abdominal tumor: Peritoneal solitary fibrous tumor. Gastrointest. Cancer Res. 2012, 5, 179–180. [Google Scholar]

- Awan, A.; Johnston, D.E.; Jamal, M.M. Gastric outlet obstruction with benign endoscopic biopsy should be further explored for malignancy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 1998, 48, 497–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, H.I.; Tharian, B.; Inamdar, S.; Garcia-Saenz-de-Sicilia, M.; Cengiz, C. Recent advances in endoscopic management of gastric neoplasms. World J. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2023, 15, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichikawa, S.; Onishi, H. Computed tomography findings of abnormal gas in the abdomen and pelvis. Singap. Med. J. 2022, 63, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alattar, Z.; Keric, N. Evaluation of Abdominal Emergencies. Surg. Clin. North. Am. 2023, 103, 1043–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, H.; Ma, Q.; Li, A.; Wang, P.; Gao, Y.; Yao, Q.; Hu, Y.; Ye, X. Diagnostic Performance of US and MRI in Predicting Malignancy of Soft Tissue Masses: Using a Scoring System. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 853232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.G.; Kim, C.G. Endoscopic stenting for malignant gastric outlet obstruction: Focusing on comparison of endoscopic stenting and surgical gastrojejunostomy. Clin. Endosc 2024, 57, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, F.; Zheng, Z.; Liu, X.; Yin, J.; Fan, Z.; Zhang, J. Gastric emptying performance of stomach-partitioning gastrojejunostomy versus conventional gastrojejunostomy for treating gastric outlet obstruction: A retrospective clinical and numerical simulation study. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1109295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, N.V.; Thong, D.Q.; Dat, T.Q.; Nguyen, D.T.; Quoc, H.L.M.; Minh, T.A.; Anh, N.V.T.; Vuong, N.L.; Trung, T.T.; Bac, N.H.; et al. Stomach-partitioning versus conventional gastrojejunostomy for unresectable gastric cancer with gastric outlet obstruction: A propensity score matched cohort study. Am. J. Surg. 2024, 228, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterpetti, A.V.; Fiori, E.; Sapienza, P.; Lamazza, A. Complications After Endoscopic Stenting for Malignant Gastric Outlet Obstruction: A Cohort Study. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. Percutaneous Tech. 2019, 29, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stawowy, M.; Kruse, A.; Mortensen, F.V.; Funch-Jensen, P. Endoscopic stenting for malignant gastric outlet obstruction. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. Percutaneous Tech. 2007, 17, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeurnink, S.M.; Steyerberg, E.W.; van Hooft, J.E.; van Eijck, C.H.; Schwartz, M.P.; Vleggaar, F.P.; Kuipers, E.J.; Siersema, P.D.; Group, D.S.S. Surgical gastrojejunostomy or endoscopic stent placement for the palliation of malignant gastric outlet obstruc-tion (SUSTENT study): A multicenter randomized trial. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2010, 71, 490–499. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Lin, S.; Yang, C.; Chen, B.; Li, W. Efficacy and long-term prognosis of gastrojejunostomy for malignant gastric outlet obstruction: A systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 49, 106967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugazza, A.; Andreozzi, M.; Asadzadeh Aghdaei, H.; Insausti, A.; Spadaccini, M.; Colombo, M.; Carrara, S.; Terrin, M.; De Marco, A.; Franchellucci, G.; et al. Management of Malignant Gastric Outlet Obstruction: A Comprehensive Review on the Old, the Classic and the Innovative Approaches. Medicina 2024, 60, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagaraja, V.; Eslick, G.D.; Cox, M.R. Endoscopic stenting versus operative gastrojejunostomy for malignant gastric outlet obstruction-a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and non-randomized trials. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2014, 5, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Sunde, B.; Tsekrekos, A.; Hayami, M.; Rouvelas, I.; Nilsson, M.; Lindblad, M.; Klevebro, F. Partial stom-ach-partitioning gastrojejunostomy for gastric outlet obstruction: A cohort study based on consecutive case series from a single center. Asian J. Surg. 2022, 45, 326–331. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, M.F.K.P.; Pereira, M.A.; Dias, A.R.; Yagi, O.K.; Zilberstein, B.; Ribeiro-Junior, U. Gastric partitioning versus gastrojejunostomy for gastric outlet obstruction due to unresectable gastric cancer: Randomized clinical trial. BJS Open 2025, 9, zrae152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canakis, A.; Bomman, S.; Lee, D.U.; Ross, A.; Larsen, M.; Krishnamoorthi, R.; Alseidi, A.A.; Adam, M.A.; Kouanda, A.; Sharaiha, R.Z. Benefits of EUS-guided gastroenterostomy over surgical gastrojejunostomy in the palliation of malignant gastric outlet obstruction: A large multicenter experience. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2023, 98, 348–359. e330. [Google Scholar]

- Cobb, W.; Harris, S.; Xavier, J.; de la Fuente, S.G. Systematic review of long-term effectiveness of endoscopic gastrojejunostomy in patients presenting with gastric outlet obstruction from periampullary malignancies. Surg. Endosc. 2024, 38, 4680–4685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanella, G.; Dell'Anna, G.; Capurso, G.; Maisonneuve, P.; Bronswijk, M.; Crippa, S.; Tamburrino, D.; Macchini, M.; Orsi, G.; Casadei-Gardini, A.; et al. EUS-guided gastroenterostomy for management of malignant gastric outlet obstruction: A prospec-tive cohort study with matched comparison with enteral stenting. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2023, 98, 337–347.e335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasam, R.T.; Mathews, T.; Schuster, K.F.; Szvarca, D.; Walradt, T.; Jirapinyo, P.; Thompson, C.C. EUS-guided gastroenteros-tomy for malignant gastric outlet obstruction: Impact of clinical and demographic factors on outcomes. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2025, 101, 580–588.e581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.; Benchaya, J.A.; Martel, M.; Barkun, A.; Wyse, J.M.; Ferri, L.; Chen, Y.I. EUS-guided gastroenterostomy vs. surgical gastrojejunostomy and enteral stenting for malignant gastric outlet obstruction: A meta-analysis. Endosc. Int. Open 2023, 11, E660–E672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, L.; Reddy, V.V.; Gavini, S.K.; Chandrakasan, C. Impact of route of reconstruction of gastrojejunostomy on delayed gastric emptying after pancreaticoduodenectomy: A prospective randomized study. Ann. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Surg. 2023, 27, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsutaho, A.; Nakamura, T.; Asano, T.; Okamura, K.; Tsuchikawa, T.; Noji, T.; Nakanishi, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Murakami, S.; Ku-rashima, Y.; et al. Delayed Gastric Emptying in Side-to-Side Gastrojejunostomy in Pancreaticoduodenectomy: Result of a Propensity Score Matching. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2017, 21, 1635–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quero, G.; Menghi, R.; Fiorillo, C.; Laterza, V.; De Sio, D.; Schena, C.A.; Di Cesare, L.; Cina, C.; Longo, F.; Rosa, F.; et al. The impact of gastrojejunostomy orientation on delayed gastric emptying after pancreaticoduodenectomy: A single center com-parative analysis. HPB 2022, 24, 654–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doberneck, R.C.; Berndt, G.A. Delayed gastric emptying after palliative gastrojejunostomy for carcinoma of the pancreas. Arch. Surg. 1987, 122, 827–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomman, S.; Ghafoor, A.; Sanders, D.J.; Jayaraj, M.; Chandra, S.; Krishnamoorthi, R. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastro-enterostomy versus surgical gastrojejunostomy in treatment of malignant gastric outlet obstruction: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Endosc. Int. Open 2022, 10, E361–E368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarra, G.; Musolino, C.; Venneri, A.; De Marco, M.L.; Bartolotta, M. Palliative antecolic isoperistaltic gastrojejunostomy: A randomized controlled trial comparing open and laparoscopic approaches. Surg. Endosc. And. Other Interv. Tech. 2006, 20, 1831–1834. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.P.; Tabrizian, P.; Nguyen, S.; Telem, D.; Divino, C. Laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy for the treatment of gastric outlet obstruction. Jsls 2011, 15, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, Y.; Takiguchi, S.; Takahashi, T.; Kurokawa, Y.; Makino, T.; Yamasaki, M.; Nakajima, K.; Mori, M.; Doki, Y. Treatment of gastric outlet obstruction that results from unresectable gastric cancer: Current evidence. World J. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2016, 8, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.-B. Laparoscopic gatrojejunostomy for palliation of gastric outlet obstruction in unresectable gastric cancer. Surg. En-dosc. 2002, 16, 1620–1626. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, J.I.; Kutscher, M.; Lemus, M.; Crovari, F.; Pimentel, F.; Briceño, E. Palliative gastrojejunostomy in unresectable cancer and gastric outlet obstruction: A retrospective cohort study. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2021, 103, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazanjian, K.K.; Reber, H.A.; Hines, O.J. Laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy for gastric outlet obstruction in pancreatic cancer. Am. Surg. 2004, 70, 910–913. [Google Scholar]

- Lorusso, D.; Giliberti, A.; Bianco, M.; Lantone, G.; Leandro, G. Stomach-partitioning gastrojejunostomy is better than conven-tional gastrojejunostomy in palliative care of gastric outlet obstruction for gastric or pancreatic cancer: A meta-analysis. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2019, 10, 283. [Google Scholar]

- Arigami, T.; Uenosono, Y.; Ishigami, S.; Yanagita, S.; Okubo, K.; Uchikado, Y.; Kita, Y.; Mori, S.; Kurahara, H.; Maemura, K. Clinical impact of stomach-partitioning gastrojejunostomy with braun enteroenterostomy for patients with gastric outlet ob-struction caused by unresectable gastric cancer. Anticancer. Res. 2016, 36, 5431–5436. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-lah-Fernández, O.; Parreño-Manchado, F.C.; García-Plaza, A.; Álvarez-Delgado, A. Partial stomach partitioning gas-trojejunostomy in the treatment of the malignantgastric outlet obstruction. Cirugía Y Cir 2015, 83, 386–392. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Zheng, Z.; Xue, Y.; Yin, J.; Zhang, J. Exploring the safety and efficacy of stomach-partitioning gastrojeju-nostomy with distal selective vagotomy versus conventional gastrojejunostomy with highly selective vagotomy for treating benign gastric outlet obstruction: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e070735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeurnink, S.M.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Vleggaar, F.P.; van Eijck, C.H.; van Hooft, J.E.; Schwartz, M.P.; Kuipers, E.J.; Siersema, P.D. Predictors of survival in patients with malignant gastric outlet obstruction: A patient-oriented decision approach for palliative treatment. Dig. Liver Dis. 2011, 43, 548–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terashima, M.; Fujitani, K.; Ando, M.; Sakamaki, K.; Kawabata, R.; Ito, Y.; Yoshikawa, T.; Kondo, M.; Kodera, Y.; Kaji, M.; et al. Survival analysis of a prospective multicenter observational study on surgical palliation among patients receiving treatment for malignant gastric outlet obstruction caused by incurable advanced gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer 2021, 24, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Felice, F.; Malerba, S.; Nardone, V.; Salvestrini, V.; Calomino, N.; Testini, M.; Boccardi, V.; Desideri, I.; Gentili, C.; De Luca, R.; et al. Progress and Challenges in Integrating Nutritional Care into Oncology Practice: Results from a National Survey on Behalf of the NutriOnc Research Group. Nutrients 2025, 17, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drapek, L.C.; Kerlan, R.K., Jr.; Acquisto, S. Guidelines for biliary stents and drains. Chin. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, J.M. Management of Malignant Biliary Obstruction. Semin. Interv. Radiol. 2016, 33, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhusudhan, K.S.; Gamanagatti, S.; Srivastava, D.N.; Gupta, A.K. Radiological interventions in malignant biliary obstruction. World J. Radiol. 2016, 8, 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Wu, X. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage for distal biliary malignant obstructive jaundice. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.; Rostamianmoghaddam, Y.; Khakban, A.; Barkun, A.; Chen, Y. A102 Eus-Guided Gastroenterostomy is Cost-Effective Compared to Surgical Gastrojejunostomy and Enteral Stenting for Palliation of Malignant Gastric Outlet Obstruction. J. Can. Assoc. Gastroenterol. 2024, 7, 74–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K.; Itoi, T. Recent developments in endoscopic ultrasonography-guided gastroenterostomy. Int. J. Gastrointest. Interv. 2020, 9, 177–183. [Google Scholar]

| Feature | GJ | SPGJ | EUS-GE |

|---|---|---|---|

| DGE Rate | High (26–43.6%) | Low (2.1–6.7%) | Low to intermediate (needs more data) |

| Oral Intake Recovery | Moderate | Faster | Moderate to fast |

| Technical Complexity | Moderate | Higher than GJ | High (requires EUS expertise) |

| Long-Term Patency | Good | Better | Promising (needs more data) |

| Suitability | General | Good performance status | Specialized centers (requires EUS setup) |

| Procedure time (minutes) | 90–170 | 90–150 | 35–96 |

| Hospital stay (days) | 9–10 | 7–9 | 2–7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeong, S.-H.; Park, M.; Seo, K.W.; Min, J.-S. Advances in Surgical Management of Malignant Gastric Outlet Obstruction. Cancers 2025, 17, 2567. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17152567

Jeong S-H, Park M, Seo KW, Min J-S. Advances in Surgical Management of Malignant Gastric Outlet Obstruction. Cancers. 2025; 17(15):2567. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17152567

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeong, Sang-Ho, Miyeong Park, Kyung Won Seo, and Jae-Seok Min. 2025. "Advances in Surgical Management of Malignant Gastric Outlet Obstruction" Cancers 17, no. 15: 2567. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17152567

APA StyleJeong, S.-H., Park, M., Seo, K. W., & Min, J.-S. (2025). Advances in Surgical Management of Malignant Gastric Outlet Obstruction. Cancers, 17(15), 2567. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17152567