Distinctive Characteristics of Rare Sellar Lesions Mimicking Pituitary Adenomas: A Collection of Unusual Neoplasms

Simple Summary

Abstract

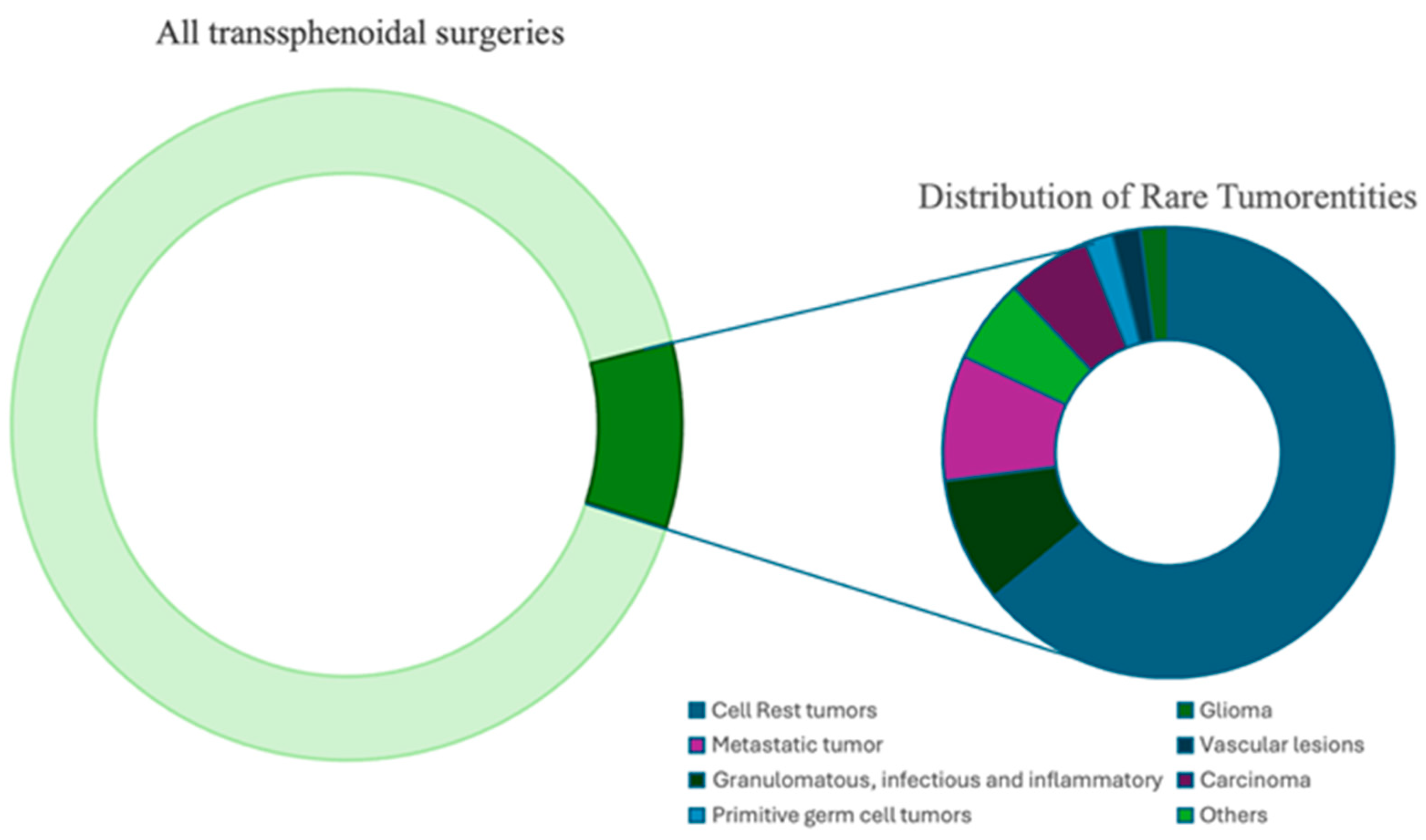

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Imaging, Histopathological Diagnosis, and Treatment Modalities

3. Results

3.1. Histopathological Analysis and Location

3.2. Neurological and Endocrinological Characteristics

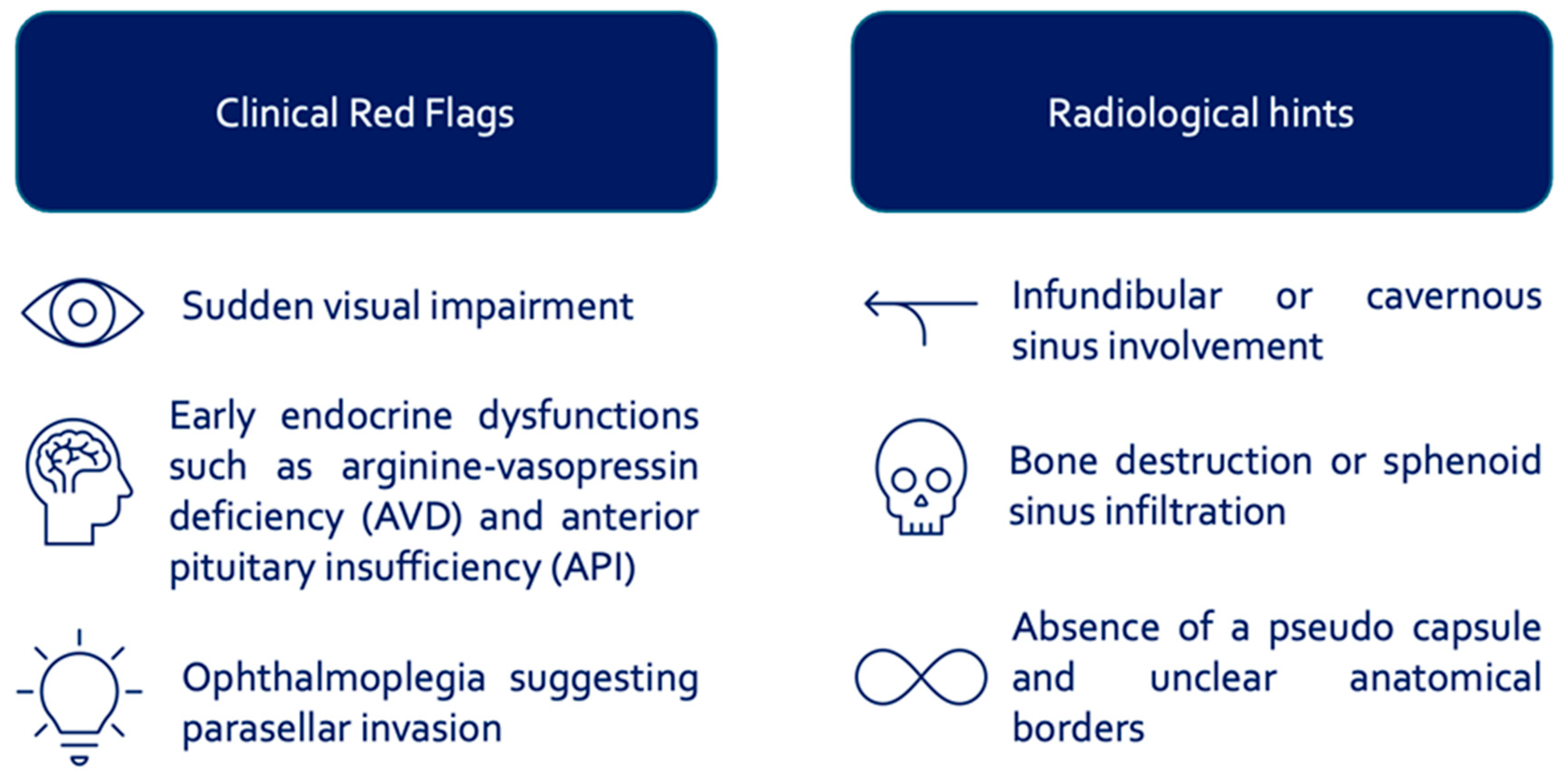

3.3. Imaging Characteristics

3.4. Treatment and Outcome

3.5. Complications

4. Discussion

4.1. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Considerations

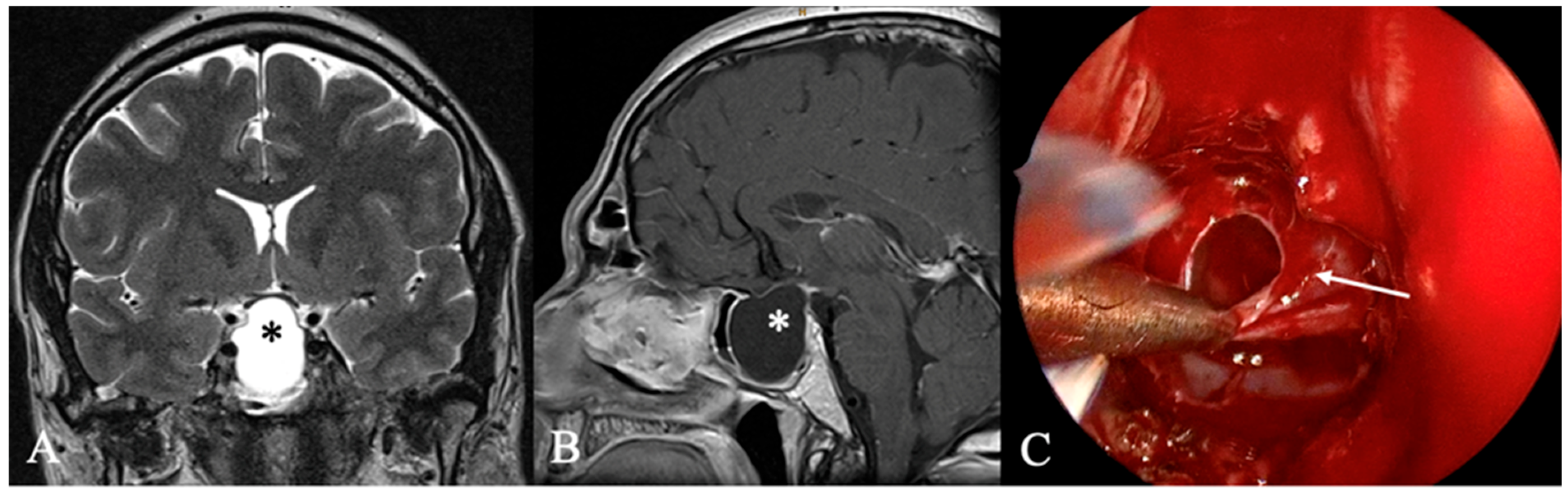

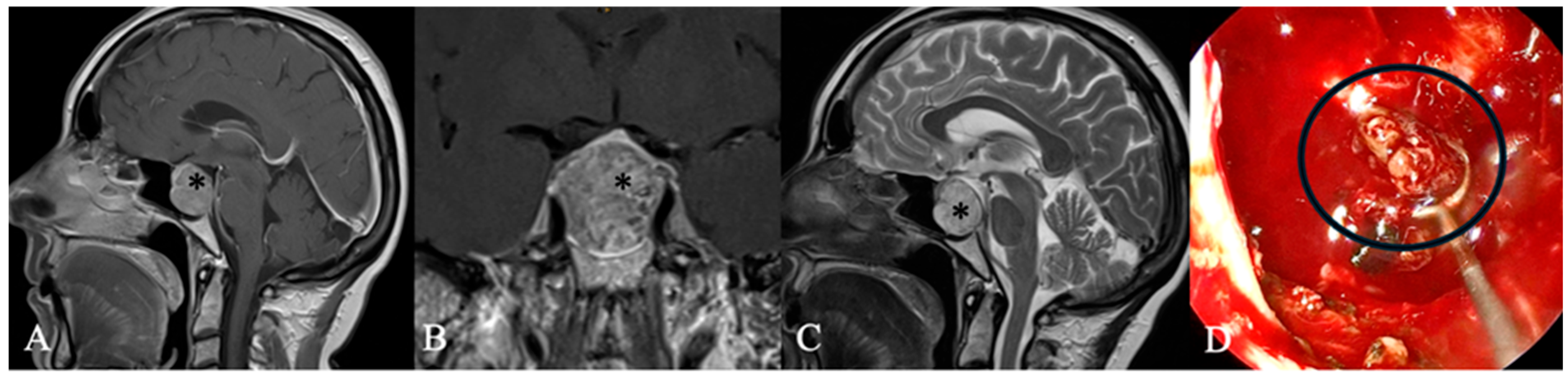

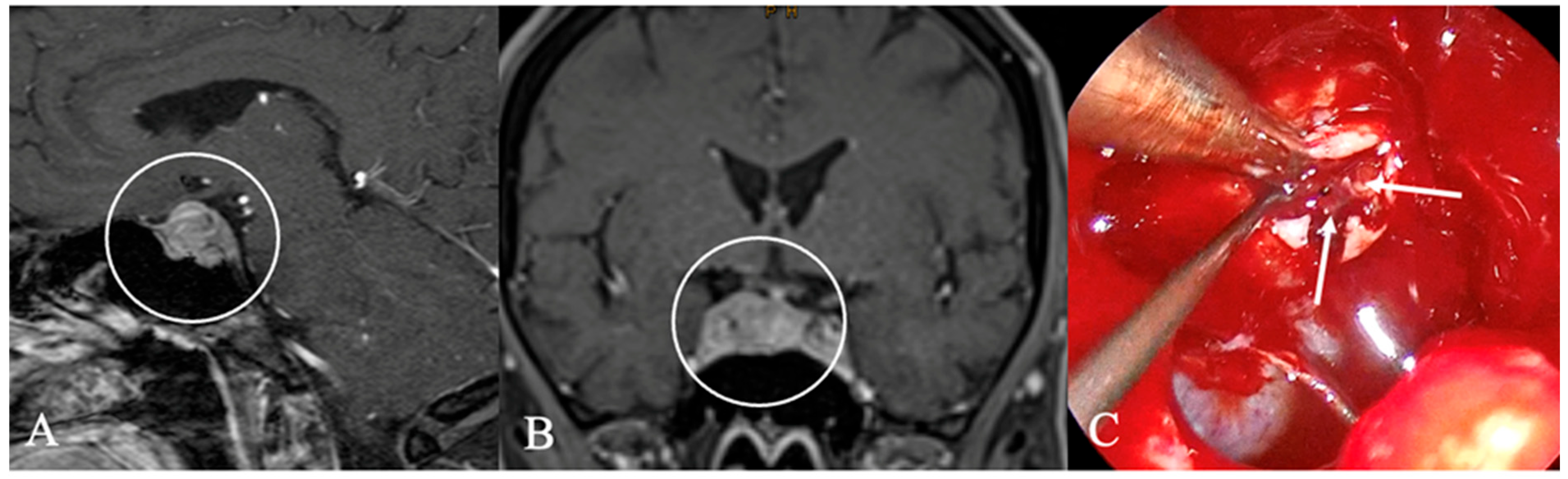

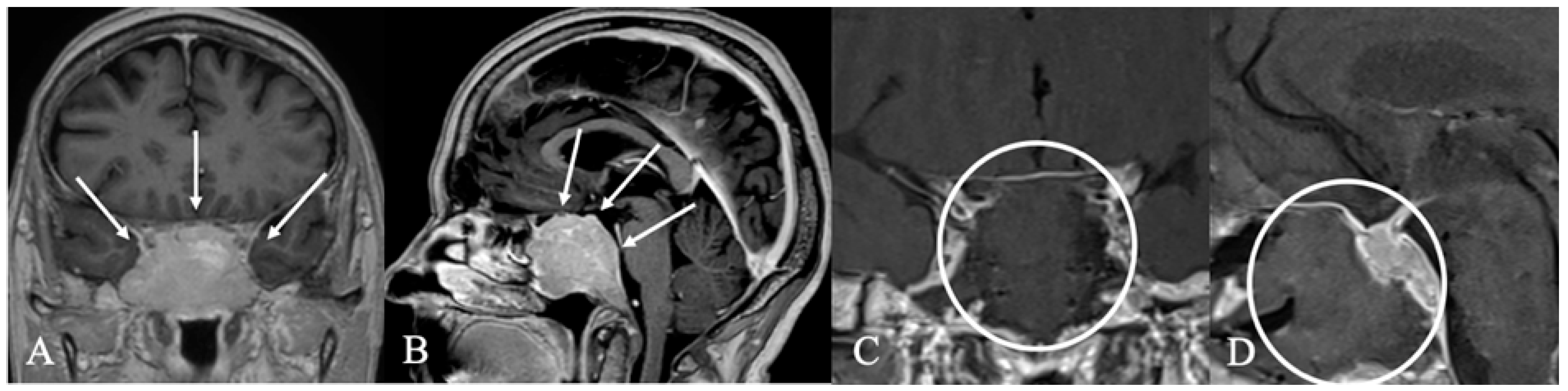

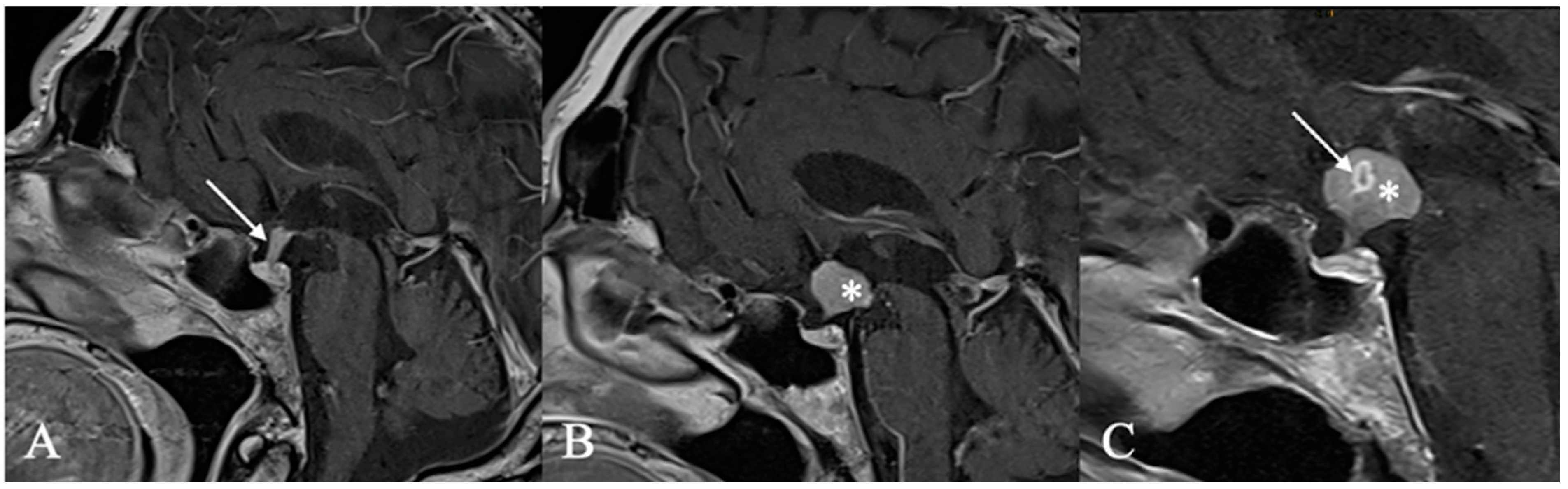

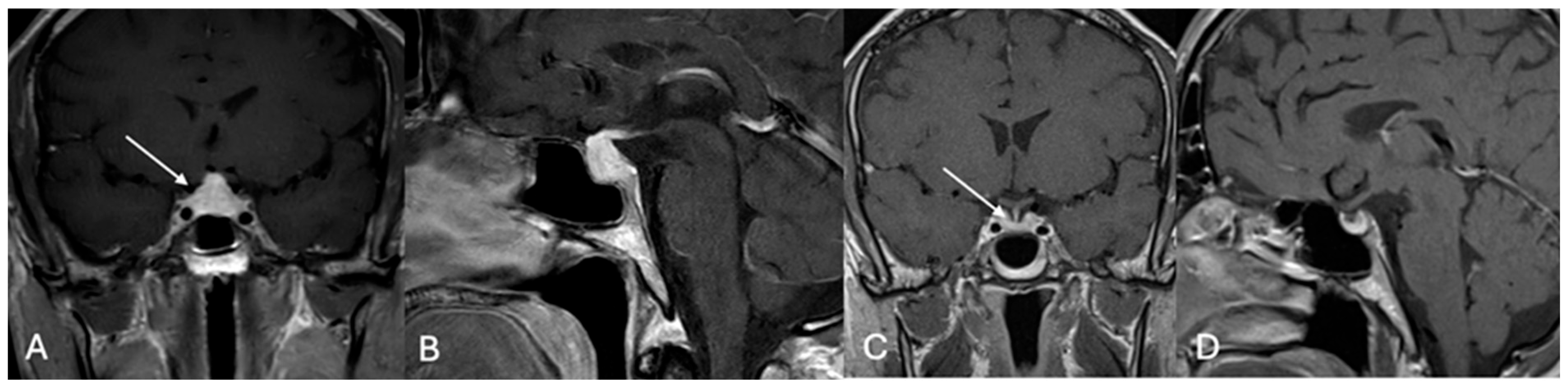

4.2. Differential Diagnoses and Case Presentations

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AH | Autoimmune Hypophysitis |

| API | Anterior Pituitary Insufficiency |

| AML | Acute Myeloid Leukemia |

| AVD | Arginine-Vasopressin deficiency |

| BD | Bone Destruction |

| CP | Craniopharyngiomas |

| CO | Chiasma Opticum |

| CSI | Cavernosus Sinus Infiltration |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal Fluid |

| D | Dizziness |

| ENT | Ear Nose Throat |

| EoR | Extent of Resection |

| ES | Extrasellar |

| Gd | Gadolinium |

| GII | Granulotaous Infectious Inflammatory |

| HA | Headache |

| I | Infundibulum |

| MR | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| NPC | Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma |

| ONB | Olfactory Neuroblastoma |

| IS | Intrasellar |

| IP | Inverted Papilloma |

| PitNET | Pituitary Neuroendocrine Tumor |

| PS | Parasellar |

| PFS | Progression-free survival |

| SS | Suprasellar |

| SH | Secondary Hypogonadism |

| SSI | Sphenoid Sinus Infiltration |

| VI | Visual Impairment |

References

- McDowell, B.D.; Wallace, R.B.; Carnahan, R.M.; Chrischilles, E.A.; Lynch, C.F.; Schlechte, J.A. Demographic differences in incidence for pituitary adenoma. Pituitary 2010, 14, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freda, P.U.; Post, K.D. Differential diagnosis of sellar masses. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 1999, 28, 81–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glezer, A.; Paraiba, D.B.; Bronstein, M.D. Rare sellar lesions. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2008, 37, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koutourousiou, M.; Kontogeorgos, G.; Seretis, A. Non-adenomatous sellar lesions: Experience of a single centre and review of the literature. Neurosurg. Rev. 2010, 33, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somma, T.; Solari, D.; Beer-Furlan, A.; Guida, L.; Otto, B.; Prevedello, D.; Cavallo, L.M.; Carrau, R.; Cappabianca, P. Endoscopic Endonasal Management of Rare Sellar Lesions: Clinical and Surgical Experience of 78 Cases and Review of the Literature. World Neurosurg. 2017, 100, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, K.S.; Choudhary, S.; Ganesan, P.K.; Sood, N.; Ramalingum, W.B.S.; Basil, R.; Dhawan, S. Sphenoid sinus anatomical variants and pathologies: Pictorial essay. Neuroradiology 2023, 65, 1187–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, Y.-H.; Seo, Y.; Kim, O.L. The surgical outcomes following transsphenoidal surgery for Rathke cleft cysts: Comparison of the surgical approaches at a single institution. Medicine 2022, 101, e32421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, J.; Kanaan, I.; Al Homsi, M. Non-neoplastic cystic lesions of the sellar region presentation, diagnosis and management of eight cases and review of the literature. Acta Neurochir. 1999, 141, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.Y.; Castillo, M. Nonadenomatous tumors of the pituitary and sella turcica. Top. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2005, 16, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karavitaki, N. Radiotherapy of other sellar lesions. Pituitary 2008, 12, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solari, D.; d’Avella, E.; Barkhoudarian, G.; Zoli, M.; Cheok, S.; Bove, I.; Fabozzi, G.L.; Zada, G.; Mazzatenta, D.; Kelly, D.F.; et al. Indications and Outcomes of the Extended Endoscopic Endonasal Approach for the Removal of “Unconventional” Suprasellar Pituitary Neuroendocrine Tumors. J. Neurosurg. 2025, 143, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlaváč, M.; Knoll, A.; Mayer, B.; Braun, M.; Karpel-Massler, G.; Etzrodt-Walter, G.; Coburger, J.; Wirtz, C.R.; Paľa, A. Ten years’ experience with intraoperative MRI-assisted transsphenoidal pituitary surgery. Neurosurg. Focus. 2020, 48, E14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magro, E.; Graillon, T.; Lassave, J.; Castinetti, F.; Boissonneau, S.; Tabouret, E.; Fuentes, S.; Velly, L.; Gras, R.; Dufour, H. Complications Related to the Endoscopic Endonasal Transsphenoidal Approach for Nonfunctioning Pituitary Macroadenomas in 300 Consecutive Patients. World Neurosurg. 2016, 89, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, S.; Gardner, P.A.; Koutourousiou, M.; Kubik, M.; Fernandez-Miranda, J.C.; Snyderman, C.H.; Wang, E.W. Risk Factors Associated with Postoperative Cerebrospinal Fluid Leak after Endoscopic Endonasal Skull Base Surgery. J. Neurosurg. 2018, 128, 1066–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halvorsen, H.; Ramm-Pettersen, J.; Josefsen, R.; Rønning, P.; Reinlie, S.; Meling, T.; Berg-Johnsen, J.; Bollerslev, J.; Helseth, E. Surgical Complications after Transsphenoidal Microscopic and Endoscopic Surgery for Pituitary Adenoma: A Consecutive Series of 506 Procedures. Acta Neurochir. 2014, 156, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadelha, M.R.; Wildemberg, L.E.; Lamback, E.B.; Barbosa, M.A.; Kasuki, L.; Ventura, N. Approach to the Patient: Differential Diagnosis of Cystic Sellar Lesions. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 107, 1751–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Famini, P.; Maya, M.M.; Melmed, S. Pituitary magnetic resonance imaging for sellar and parasellar masses: Ten-year experience in 2598 patients. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 1633–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Li, C.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, L.; Qin, G.; Wang, S.; Xu, L. Analysis of the Clinical Characteristics and Pituitary Function of Patients in Central China With Rathke’s Cleft Cysts. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 800135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langlois, F.; Varlamov, E.V.; Fleseriu, M. Hypophysitis, the Growing Spectrum of a Rare Pituitary Disease. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 107, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulici, V.; Hart, J. Chordoma: A Review and Differential Diagnosis. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2021, 146, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Ikawa, F.; Kurisu, K.; Arita, K.; Takaba, J.; Kanou, Y. Quantitative MR Evaluation of Intracranial Epidermoid Tumors by Fast Fluid-attenuated Inversion Recovery Imaging and Echo-planar Diffusion-weighted Imaging. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2001, 22, 1089–1096. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7974800/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Abele, T.; Yetkin, Z.; Raisanen, J.; Mickey, B.; Mendelsohn, D. Non-pituitary origin sellar tumours mimicking pituitary macroadenomas. Clin. Radiol. 2012, 67, 821–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Liu, X.; Li, W.; Chen, D. Pituicytoma: A report of three cases and literature review. Oncol. Lett. 2016, 12, 3417–3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brat, D.J.; Scheithauer, B.W.; Staugaitis, S.M.; Holtzman, R.N.N.; Morgello, S.; Burger, P.C. Pituicytoma: A distinctive low-grade glioma of the neurohypophysis. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2000, 24, 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figarella-Branger, D.; Dufour, H.; Fernandez, C.; Bouvier-Labit, C.; Grisoli, F.; Pellissier, J. Pituicytomas, a mis-diagnosed benign tumor of the neurohypophysis: Report of three cases. Acta Neuropathol. 2002, 104, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtado, S.V.; Ghosal, N.; Venkatesh, P.K.; Gupta, K.; Hegde, A.S. Diagnostic and clinical implications of pituicytoma. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2010, 17, 938–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uesaka, T.; Miyazono, M.; Nishio, S.; Iwaki, T. Astrocytoma of the pituitary gland (pituicytoma): Case report. Neuroradiology 2002, 44, 123–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, T.R.; D’ANgelo, C.M.; Clasen, R.A.; Wilkinson, S.B.; Passavoy, R.D. Magnetic resonance imaging and pathological analysis of a pituicytoma: Case report. Neurosurgery 1994, 35, 314–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komninos, J.; Vlassopoulou, V.; Protopapa, D.; Korfias, S.; Kontogeorgos, G.; Sakas, D.E.; Thalassinos, N.C. Tumors metastatic to the pituitary gland: Case report and literature review. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 89, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhardt, T.; Henze, M.; Kluth, L.A.; Westphal, M.; Schmidt, N.O.; Flitsch, J. Surgical management of pituitary metastases. Pituitary 2015, 19, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Kumar, P.; Chandrashekhara, S.H.; Kumar, A. Unravelling chloroma: Review of imaging findings. Br. J. Radiol. 2017, 90, 20160710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na’ARa, S.; Amit, M.; Billan, S.; Gil, Z. Plasmacytoma of the Skull Base: A Meta-Analysis. J. Neurol. Surg. Part B Skull Base 2015, 77, 061–065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, H.; Elouaouch, S.; el Youssi, Z.; Guerrouaz, M.A.; Moukhlissi, M.; Berhili, S.; Mezouar, L. Solitary plasmacytoma of the skull base: A case report and literature review. Radiol. Case Rep. 2023, 18, 3894–3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyag, A.; Soni, T.P.; Gupta, A.K.; Sharma, L.M.; Jakhotia, N.; Sharma, S. Plasmacytoma of the Skull-base: A Rare Tumor. Cureus 2018, 10, e2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knobel, D.; Zouhair, A.; Tsang, R.W.; Poortmans, P.; Belkacémi, Y.; Bolla, M.; Oner, F.D.; Landmann, C.; Castelain, B.; Ozsahin, M.; et al. Prognostic factors in solitary plasmacytoma of the bone: A multicenter Rare Cancer Network study. BMC Cancer 2006, 6, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, H.; Kainz, S.; Schreder, M.; Zojer, N.; Hinke, A. SLiM CRAB criteria revisited: Temporal trends in prognosis of patients with smoldering multiple myeloma who meet the definition of ‘biomarker-defined early multiple myeloma’—A systematic review with meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 58, 101910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufmann, T.J.; Lopes, M.B.S.; Laws, E.R.; Lipper, M.H. Primary Sellar Lymphoma: Radiologic and Pathologic Findings in Two Patients. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2002, 23, 364–367. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7975309/ (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Ren, S.; Lu, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, B.; Li, M. Coexistence of Pituitary Adenoma and Primary Pituitary Lymphoma: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Front. Surg. 2022, 9, 842830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutenberg, A.; Larsen, J.; Lupi, I.; Rohde, V.; Caturegli, P. A radiologic score to distinguish autoimmune hypophysitis from nonsecreting pituitary adenoma preoperatively. ANJR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2009, 30, 1766–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, S.; Korkmaz, O.P.; Ozkaya, H.M.; Apaydin, T.; Durmaz, E.S.; Haliloglu, O.; Durcan, E.; Kadioglu, P. Primary hypophysitis: Experience of a Single Tertiary Center. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 2019, 129, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Estrada, R.A.; Kshettry, V.R.; Vogel, A.N.; Curtis, M.T.; Evans, J.J. Cholesterol granulomas presenting as sellar masses: A similar, but clinically distinct entity from craniopharyngioma and Rathke’s cleft cyst. Pituitary 2016, 20, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.S.; Schänzer, A.; Hattingen, E.; Plate, K.H.; Seifert, V. Xanthogranuloma of the sellar region. Acta Neurochir. 2005, 148, 473–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, M.T.; Gelman, R.; Hochberg, F. Intracranial germ-cell tumors: Natural history and pathogenesis. J. Neurosurg. 1985, 63, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Zhang, Q.; Kong, F.; Gao, Y. The Incidence of Invasion and Metastasis of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma at Different Anatomic Sites in the Skull Base. Anat. Rec. Adv. Integr. Anat. Evol. Biol. 2012, 295, 1252–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Hu, K.; Zhao, B.; Bian, E.; Ni, S.; Wan, J. Osteosarcoma of the Skull Base: An Analysis of 19 Cases and Literature Review. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2017, 44, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisan, Q.; Laccourreye, O.; Bonfils, P. Sinonasal inverted papilloma: From diagnosis to treatment. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2016, 133, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchwald, C.; Franzmann, M.; Tos, M. Sinonasal papillomas: A report of 82 cases in copenhagen county, including a longitudinal epidemiological and clinical study. Laryngoscope 1995, 105, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sham, C.; Woo, J.K.; Van Hasselt, C.A.; Tong, M.C. Treatment results of sinonasal inverted papilloma: An 18-Year Study. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2009, 23, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, L.D.R. Olfactory neuroblastoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2009, 3, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, N.J.; Sato, T.S. Ectopic primary olfactory neuroblastoma of the nasopharynx: A case report and review of the literature. Radiol. Case Rep. 2019, 14, 997–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, F.; Agaimy, A.; Franchi, A.; Suárez, C.; Poorten, V.V.; Mäkitie, A.A.; Homma, A.; Eisbruch, A.; Olsen, K.D.; Saba, N.F.; et al. Update on olfactory neuroblastoma. Virchows Arch. 2024, 484, 567–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, D. Sinonasal Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Current Challenges and Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment, with a Focus on Olfactory Neuroblastoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2018, 12, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Histopathological Diagnosis | No. of Patients | Extension of Sellar Lesions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

% (n) | Suprasellar % (n) | Intrasellar % (n) | Parasellar % (n) | |

| Dysontogenetic tumors, total Rathke’s cleft cyst Craniopharyngioma (extradural) Chordoma Epidermoid Colloid cyst | 64% (30) 23% (11) 2% (1) 6% (3) 2% (1) 30% (14) | 60% (18) 64% (7) 100% (1) 100% (1) 64% (9) | 97% (29) 100% (11) 100% (1) 100% (3) 100% (1) 93% (13) | 13% (4) 100% (1) 100% (3) |

| Pituicytoma | 2% (1) | 100% (1) Pituitary stalk | ||

| Metastatic tumor, total Amelanotic melanoma Chloroma Plasmocytoma Bronchial Carcinoma | 9% (4) 2% (1) 2% (1) 2% (1) 2% (1) | 50% (2) 100% (1) 100% (1) | 100% (4) 100% (1) 100% (1) 100% (1) | 75% (3) 100% (1) 100% (1) 100% (1) |

| Vascular lesions, total Endotheliod hemangioendothelioma | 2% (1) 2% (1) | 100% (1) Pituitary stalk | ||

| Granulomatous, infectious and inflammatory, total Granulomatous inflammation Pituitary abscess Hypophysitis Necrotic cholesterin granuloma | 9% (4) 2% (1) 2% (1) 2% (1) 2% (1) | 25% (1) 100% (1) | 100% (4) 100% (1) 100% (1) 100% (1) 100% (1) | |

| Carcinoma, total Nasopharyngeal High-grade osteosarcoma | 6% (3) 4% (2) 2% (1) | 100% (3) 100% (2) 100% (1) | 100% (3) 100% (2) 100% (1) | |

| Germ cell tumors, total Germinoma | 2% (1) 2% (1) | 100% (1) 100% (1) | ||

| Others Lymphoma Inverted papilloma Olfactory neuroblastoma | 6% (3) 2% (1) 2% (1) 2% (1) | 100% (1) Pituitary stalk | 100% (1) 100% (1) | 100% (1) 100% (1) |

| Total | 100% (47) | 51% (24) | 89% (42) | 23% (11) |

| Neurology | Endocrinology | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Patients % (n) | Headache % (n) | Visual Impairment % (n) | III, IV, V Palsy % (n) | API % (n) | AVD % (n) | |

| Dysontogenetic tumors Rathke’s cleft cyst and colloid cyst Craniopharyngioma Chordoma Epidermoid | 64% (30) 53% (25) 2% (1) 6% (3) 2% (1) | 37% (11) 36% (9) 100% (1) 100% (1) | 20% (6) 12% (3) 100% (1) 33% (1) 100% (1) | 7% (2) 67% (2) | 57% (17) 64% (16) 33% (1) | 10% (3) 12% (3) |

| Pituicytoma | 2% (1) | 100% (1) | *** | |||

| Metastasis | 9% (4) | 25% (1) | 100% (4) | 75% (3) | 50% (2) | 25% (1) |

| Vascular lesions | 2% (1) | 100% (1) | 100% (1) | |||

| GII | 9% (4) | 50% (2) | 75% (3) | 100% (4) | 50% (2) | |

| Carcinoma | 6% (3) | 33% (1) | 33% (1) | 67% (2) | 33% (1) | |

| Germinoma | 2% (1) | 100% (1) | ||||

| Others: Lymphoma Inverted papilloma Olfactory neuroblastoma | 6% (3) 2% (1) 2% (1) 2% (1) | 33% (1) 100% (1) | 33% (1) 100% (1) | 33% (1) 100% (1) | ||

| Total | 100% (47) | |||||

| MRI | CT | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor Entity % (n) | Contrast enhancement % (n) | Infundibulum % (n) | Chiasma % (n) | Bone destruction % (n) | Sphenoid sinus infiltration % (n) |

| Dysontogenetic tumors 64% (30) | 43% (13) inhomogeneous 47% (14) marginal | 20% (6) infiltrated | 37% (11) contact 13% (4) compression | 10% (3) osteolytic 7% (2) infiltrated | 17% (5) |

| Pituicytoma 2% (1) | 100% (1) homogeneous | 100% (1) infiltrated | 100% (1) compression | ||

| Metastasis 9% (4) | 75% (3) inhomogeneous 25% (1) homogeneous | 75% (3) infiltrated | 75% (3) compression | 75% (3) osteolytic | 75% (3) |

| Vascular 2% (1) | 100% (1) inhomogeneous | 100% (1) infiltrated | 100% (1) contact | ||

| GII 9% (4) | 25% (1) inhomogeneous 50% (2) homogeneous 25% (1) marginal | 25% (1) infiltrated | 75% (3) contact 25% (1) compression | 25% (1) osteolytic | 25% (1) |

| Carcinoma 6% (3) | 33% (1) inhomogeneous 67% (2) homogeneous | 100% (1) infiltrated | 66% (2) | ||

| Germinoma 2% (1) | 100% (1) inhomogeneous | 100% (1) infiltrated | 100% (1) compression | ||

| Others: 6% (3) | 100% (3) inhomogeneous | 33% (1) infiltrated | 66% (2) osteolytic | 66% (2) | |

| Total: 100% (47) | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pala, A.; Grübel, N.; Knoll, A.; Durner, G.; Etzrodt-Walter, G.; Roßkopf, J.; Jankovic, P.; Osterloh, A.; Scheithauer, M.; Wirtz, C.R.; et al. Distinctive Characteristics of Rare Sellar Lesions Mimicking Pituitary Adenomas: A Collection of Unusual Neoplasms. Cancers 2025, 17, 2568. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17152568

Pala A, Grübel N, Knoll A, Durner G, Etzrodt-Walter G, Roßkopf J, Jankovic P, Osterloh A, Scheithauer M, Wirtz CR, et al. Distinctive Characteristics of Rare Sellar Lesions Mimicking Pituitary Adenomas: A Collection of Unusual Neoplasms. Cancers. 2025; 17(15):2568. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17152568

Chicago/Turabian StylePala, Andrej, Nadja Grübel, Andreas Knoll, Gregor Durner, Gwendolin Etzrodt-Walter, Johannes Roßkopf, Peter Jankovic, Anja Osterloh, Marc Scheithauer, Christian Rainer Wirtz, and et al. 2025. "Distinctive Characteristics of Rare Sellar Lesions Mimicking Pituitary Adenomas: A Collection of Unusual Neoplasms" Cancers 17, no. 15: 2568. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17152568

APA StylePala, A., Grübel, N., Knoll, A., Durner, G., Etzrodt-Walter, G., Roßkopf, J., Jankovic, P., Osterloh, A., Scheithauer, M., Wirtz, C. R., & Hlaváč, M. (2025). Distinctive Characteristics of Rare Sellar Lesions Mimicking Pituitary Adenomas: A Collection of Unusual Neoplasms. Cancers, 17(15), 2568. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17152568