Simple Summary

This communication reviews how environmental exposures to air pollution, tobacco smoke, extreme weather events, and pesticides can negatively affect the health and survival of childhood cancer survivors. We recommend the development of an environmental referral service to help address and decrease these risks. Including environmental health in pediatric cancer care will help support healthier choices, inform families, and improve long-term outcomes for childhood cancer patients.

Abstract

Childhood cancer survivors (CCSs) are at increased risk for chronic health issues due to late effects of cancer and its treatment. We address the impact of environmental exposures, such as air pollution, tobacco smoke, extreme weather events, and pesticides, on the health and survival of CCSs. These environmental hazards have been associated with worsening health outcomes and decreased survival among CCSs on a global scale. We also highlight that providers at a major pediatric cancer center in the United States have limited knowledge and practical skills about environmental risk factors and how to reduce exposures. Our survey results show that pediatric oncology providers would find an environmental referral service helpful and useful in their department. Integrating environmental health into pediatric cancer care can empower patients and families, promote healthier behaviors, and potentially reduce morbidity and mortality in this vulnerable population.

1. Introduction

Childhood cancer survivors (CCSs) are a vulnerable population at risk of chronic health conditions due to late effects of cancer and its treatment. The growing number of survivors of childhood cancers has led to an increase and acceleration in life-long and chronic health issues. By age 50, 99% of childhood cancer survivors have at least one chronic health problem [1]. Global studies have shown that survival and health outcomes among children, adolescents, and young adults with cancer are impacted by social determinants of health, including the environment to which they are exposed [2,3,4,5].

There has been growing concern over the impact of environmental exposures, such as air pollution, tobacco smoke, extreme weather, and pesticides on the outcomes and general health of pediatric cancer survivors. Although these are not the only environmental exposures that can affect the morbidity and mortality of CCS, they are among those most directly supported by evidence in the existing literature. However, there is a knowledge gap present among providers in discussing the impact of environmental exposures on the health of pediatric cancer patients. We review the existing literature on these specific exposures and recommend the development of an environmental referral service to address these concerns by providing evidence-based mitigation strategies, potentially contributing to improved health outcomes and surivival in childhood cancer survivors. This communication presents emerging evidence and a practical proposal for addressing environmental risk in childhood cancer survivorship.

2. Environmental Exposures Are Linked to Health Outcomes in Childhood Cancer Survivors

Air pollution is a significant environmental exposure that adversely affects the health of cancer survivors. Living in areas of high air pollution, defined as exposure to fine particles ≤ 2.5 microns in diameter, PM2.5, has been significantly associated with decreased survival among children with cancer, regardless of socioeconomic status [6]. Another study of pediatric cancer survivors in Utah reported that a higher 3-day average PM2.5 by zip code was associated with an increased odds of respiratory hospitalization (OR: 1.84; 95% CI: 1.13–3.00) [7]. In a follow-up study, the authors also reported that cumulative zip code-level estimates of PM2.5 in ambient air were positively associated with all-cause pediatric cancer mortality among survivors who had lymphoid leukemia, lymphoma, or brain tumors at five and ten years post diagnosis [8]. There were also significant associations between PM2.5 and mortality among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors [8]. Air quality standards in the United States are determined by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and were recently revised in February 2024, lowering the air quality standard for fine particulate matter (PM2.5) from 12.0 to 9.0 µg/m3 [9]. Despite this, residing in zip codes with PM2.5 levels greater than or equal to the new EPA air quality standard was also significantly associated with worse overall survival among children with cancer [6]. Another recent study found that childhood survivors of acute myeloid leukemia and hepatoblastoma in Texas experienced lower survival rates when residing near an oil or gas well at the time of diagnosis, likely due to exposure to hazardous air pollutants emitted from these sites [10]. Despite caregivers’ interest in learning more about the effects of air pollution on survivors’ health, there remains limited awareness, unsuccessful information-seeking, and minimal exposure reduction behaviors among caregivers of childhood cancer survivors [11].

Tobacco is a well-known environmental carcinogen and the leading cause of preventable death worldwide. Unfortunately, one in four childhood cancer survivors smokes [12]. Given that childhood cancer survivors are likely to have existing cardiovascular and respiratory health issues, they are at even greater risk of treatment-related morbidities and early mortality from tobacco use [13]. In one study, tobacco use increased lung cancer risk more than 20-fold in Hodgkin lymphoma survivors [14]. Another study found that paternal smoking prior to conception was associated with reduced survival in children with acute myeloid leukemia [15]. Similarly, exposure to secondhand smoke has been associated with decreased survival and increased treatment-related mortality in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia [16].

Extreme weather events pose an emerging global threat to pediatric cancer survivors by increasing exposure to environmental carcinogens and affecting cancer survival through impediments to access and delivery of care [17,18,19,20]. Extreme weather can discrupttransportation, communication, and power systems leading to delays in patient care. Sociodemographic factors, along with chronic physical and mental health issues, may predispose pediatric cancer survivors to increased vulnerability to shifting weather patterns and extreme weather events [18].

Pesticides are another important environmental toxicant used worldwide. Systematic reviews of studies have shown that pesticides are associated with poor cognitive, behavior, and motor neurological outcomes in children [21,22]. Childhood cancer survivors are especiallysusceptible to cognitive and behavioral issues because of their cancer and associated treatment;exposure to pesticides may exacerbate these risks. Although several studies have shown that pesticide exposure in children is associated with an increased risk of hematopoietic and central nervous cancers, evidence remains limited regarding the impact of such exposures on the health outcomes of childhood cancer survivors [23,24,25]. A 2019 study showed that agricultural occupational exposure to pesticides was associated with treatment failure in adults with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma [26]. A 2025 study was the first to identify reduced survival among children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia who were exposed to residential pesticides, particularly rodenticide, during pregnancy [25].

3. Addressing Environmental Health in Childhood Cancer Survivors

3.1. Survey and Focus Group

In April 2024, an institutional REDCap survey was sent via email to approximately 154 members of the oncology team at Texas Children’s Cancer and Hematology Center, a major pediatric cancer hospital in the United States. The survey was not validated prior to distribution, and IRB and ethical approval was not necessary. The survey included questions on knowledge of environmental risk factors for pediatric cancer and interest in using an environmental referral service if one were developed. The data were exported from REDCap and analyzed using qualitative methods.

A one-hour focus group discussion involving nineteen members from the Cancer and Hematology Center Family Advisory Team was then conducted and transcribed.. The Family Advisory Team consisted of family members who voluntarily indicated their interest through an engagement intake form and had a child currently undergoing or who had completed cancer treatment. The discussion revealed a strong need for the development of a pediatric cancer environmental referral service. Many families expressed frustration that healthcare providers are not prepared to address these environmental issues. Additionally, they said that they are looking for this information and currently left to search the internet, which can lead to misinformation and may be detrimental during and after their child’s cancer treatment. Overall, families felt that integrating such a service into standard clinical practice would significantly reduce the anxiety that many of them experienced during their cancer journeys, including survivorship.

3.2. Survey Results

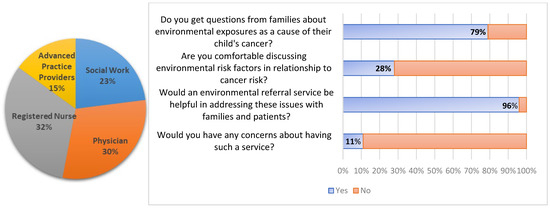

There were 49 respondents to the survey after a two-week period. In total, 30% of respondents were physicians, 15% were advanced practice providers, 32% were nurses, and 23% were social workers. Approximately 80% of respondents indicated that they receive questions from families on the impact of the environment on their child’s cancer. While most reported receiving questions, nearly 75% were not comfortable discussing the topic with families. Ninety-six percent of respondents indicated that an environmental referral service would be helpful, with most expressing interest in using the service to address concerns in addition to or in lieu of discussing them directly with families. Approximately 90% of respondents indicated that they would not have any concerns using an environmental referral service. Several respondents indicated that a referral service would be helpful to incorporate into clinical practice. Given that data are self-reported and derived from a single-center sample, results should be interpreted with caution due to potential response bias and lack of generalizability (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of oncology team members who responded to the survey (N = 49) and their experiences with receiving questions from families on environmental risk factors for pediatric cancers and interest in using an environmental referral service.

4. Discussion

Given the significant impact of environmental exposures on pediatric cancer survivors, it is important to address the limited knowledge, familiarity, and comfort of healthcare providers in discussing these topics with patients and families [27]. In response to the survey results and focus group discussion, we recommend a practical and scalable intervention to integrate environmental health into pediatric cancer care.

United States pediatric cancer environmental referral services are now under development by the Childhood Cancer and the Environment Program of the Pediatric Environmental Health Specialty Units (PEHSUs), a national network of experts in pediatric health issues that arise from environmental exposures (https://pehsu.net/program/childhood-cancer-the-environment-national-program/, accessed on 5 June 2025). The referral service will work with the PEHSU to help address the questions and concerns from patients and families and provide up-to-date and evidence-based information about environmental risk factors in addition to simple and cost-effective strategies to reduce exposure risk. Institutions may approach the integration of environmental health in pediatric cancer care differently. The referral service will be adaptable to meet this need and may be initiated at various points along the care continuum—including cancer predisposition and screening clinics, initial diagnosis, and throughout survivorship care. In Europe, the PEHSU in Murcia, Spain, has already launched the Environmental and Community Health Program for Longitudinal Follow-up of Childhood and Adolescent Cancer Survivors [28]. This program includes a pediatric environmental history tool to assess individual risk and develop low-carbon, healthy lifestyle strategies [28,29,30]. This model was presented at the Childhood Cancer Prevention Symposium held in Houston, Texas, in February 2025, where it was received with significant interest as a scalable approach to integrating environmental health into pediatric oncology care. The model may be adaptable across diverse healthcare settings nationally and internationally, building on programs like the PEHSU in Murcia, Spain.

An environmental health history and risk assessment form is also under development by the Childhood Cancer and the Environment Program and will be utilized in conjunction with the referral service. The intake form will capture the geographical locations of the patient up until their diagnosis along with details about siblings and birth order, diet and nutrition, and exposures to tobacco, indoor and outdoor air pollution, chemicals and pesticides, and UV/radiation before and after cancer diagnosis. Responses will be confidential and incorporated into the secure electronic health record as part of the patient’s social and environmental history. Based on the responses to the intake form, the referral service will offer tailored resources and counseling on protective measures to reduce risk within the home and community. As part of these resources, an environmental toolkit will be offered to families and will include affordable air quality and carbon dioxide monitors, as well as a DIY air purifier made from a box fan and HEPA filter.

5. Conclusions

We recommend the development of a dedicated pediatric cancer environmental referral service within pediatric oncology cancer centers to address environmental exposures as important and potentially modifiable risk factors in pediatric cancer patients. Healthcare providers and families have expressed a clear need for a reliable resource to help navigate environmental health concerns and mitigate risks. Integrating environmental health into pediatric cancer care would provide a valuable opportunity to address environmental exposures, empower patients and families by promoting healthier behaviors, and potentially improve long-term health outcomes by reducing morbidity and mortality in this vulnerable population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.S., N.M.W., H.M.T., M.E.S. and M.D.M.; writing—original draft preparation, O.S.; writing—review and editing, O.S., N.M.W., H.M.T., M.E.S. and M.D.M.; supervision, M.D.M.; funding acquisition, M.D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This resource was supported by cooperative agreement FAIN: NU61TS000356 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (CDC/ATSDR), totaling USD 3,673,450.00, with 73% funded by CDC/ATSDR. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) provided the remaining support through Inter-Agency Agreement 24TSS2400078 with CDC/ATSDR. The Public Health Institute supports the Pediatric Environmental Health Specialty Units as the National Program Office. The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by CDC/ATSDR, EPA, or the U.S. Government. Use of trade names that may be mentioned is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the CDC/ATSDR or EPA.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this communication are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank all childhood cancer patients and their families.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the writing of the manuscript or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CCS | Childhood cancer survivor |

| EPA | Environmental Protection Agency |

| PEHSU | Pediatric Environmental Health Specialty Unit |

| DIY | Do it yourself |

| HEPA | High-efficiency particulate air |

References

- Bhakta, N.; Liu, Q.; Ness, K.K.; Baassiri, M.; Eissa, H.; Yeo, F.; Chemaitilly, W.; Ehrhardt, M.J.; Bass, J.; Bishop, M.W.; et al. The Cumulative Burden of Surviving Childhood Cancer: An Initial Report from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. Lancet 2017, 390, 2569–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, Y.; Coven, S.L.; Park, S.; Mendonca, E.A. Social Determinants of Health and Pediatric Cancer Survival: A Systematic Review. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2022, 69, e29546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kish, J.K.; Yu, M.; Percy-Laurry, A.; Altekruse, S.F. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Cancer Survival by Neighborhood Socioeconomic Status in Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Registries. JNCI Monogr. 2014, 2014, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stenmarker, M.; Mallios, P.; Hedayati, E.; Rodriguez-Wallberg, K.A.; Johnsson, A.; Alfredsson, J.; Ekman, B.; Legert, K.G.; Borland, M.; Mellergård, J.; et al. Morbidity and Mortality among Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults with Cancer over Six Decades: A Swedish Population-Based Cohort Study (the Rebuc Study). Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2024, 42, 100925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Force, L.M.; Abdollahpour, I.; Advani, S.M.; Agius, D.; Ahmadian, E.; Alahdab, F.; Alam, T.; Alebel, A.; Alipour, V.; Allen, C.A.; et al. The Global Burden of Childhood and Adolescent Cancer in 2017: An Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 1211–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, P.E.; Zhao, J.; Liang, D.; Nogueira, L.M. Ambient Air Pollution and Survival in Childhood Cancer: A Nationwide Survival Analysis. Cancer 2024, 130, 3870–3878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, J.Y.; Hanson, H.A.; Ramsay, J.M.; Leiser, C.L.; Zhang, Y.; VanDerslice, J.A.; Pope, C.A., III; Kirchhoff, A.C. Fine Particulate Matter and Respiratory Healthcare Encounters among Survivors of Childhood Cancers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, J.Y.; Hanson, H.A.; Ramsay, J.M.; Kaddas, H.K.; Pope, C.A., III; Leiser, C.L.; VanDerslice, J.; Kirchhoff, A.C.; Pope, C.A. Fine Particulate Matter Air Pollution and Mortality among Pediatric, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancer Patients. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2020, 29, 1929–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US EPA. National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) for PM. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/pm-pollution/national-ambient-air-quality-standards-naaqs-pm (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Hoang, T.T.; Rathod, R.A.; Rosales, O.; Castellanos, M.I.; Schraw, J.M.; Burgess, E.; Peckham-Gregory, E.C.; Oluyomi, A.O.; Scheurer, M.E.; Hughes, A.E.; et al. Residential Proximity to Oil and Gas Developments and Childhood Cancer Survival. Cancer 2024, 130, 3724–3733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, A.R.; Warner, E.L.; Vaca Lopez, P.L.; Kirchhoff, A.C.; Ou, J.Y. Perceptions and Knowledge of Air Pollution and Its Health Effects among Caregivers of Childhood Cancer Survivors: A Qualitative Study. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nghiem, V.T.; Jin, J.; Mennemeyer, S.T.; Wong, F.L. Health-Related Risk Behaviors among U.S. Childhood Cancer Survivors: A Nationwide Estimate. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahalley, L.S.; Robinson, L.A.; Tyc, V.L.; Hudson, M.M.; Leisenring, W.; Stratton, K.; Mertens, A.C.; Zeltzer, L.; Robison, L.L.; Hinds, P.S. Risk Factors for Smoking among Adolescent Survivors of Childhood Cancer: A Report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2012, 58, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Travis, L.B.; Gospodarowicz, M.; Curtis, R.E.; Clarke, E.A.; Andersson, M.; Glimelius, B.; Joensuu, T.; Lynch, C.F.; van Leeuwen, F.E.; Holowaty, E.; et al. Lung Cancer Following Chemotherapy and Radiotherapy for Hodgkin’s Disease. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2002, 94, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metayer, C.; Morimoto, L.M.; Kang, A.Y.; Alvarez, J.S.; Winestone, L.E. Pre- and Post-Natal Exposures to Tobacco Smoking and Survival of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic and Myeloid Leukemias in California, United States. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2024, 33, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárceles-Álvarez, A.; Ortega-García, J.A.; López-Hernández, F.A.; Fuster-Soler, J.L.; Ramis, R.; Kloosterman, N.; Castillo, L.; Sánchez-Solís, M.; Claudio, L.; Ferris-Tortajada, J. Secondhand Smoke: A New and Modifiable Prognostic Factor in Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemias. Environ. Res. 2019, 178, 108689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, L.M.; Yabroff, K.R.; Bernstein, A. Climate Change and Cancer. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, H.M.; Sheffield, P.; Shakeel, O.; Wood, N.M.; Miller, M.D. Climate Change Will Impact Childhood Cancer Risks, Care and Outcomes. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2025, 9, e003123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiatt, R.A.; Beyeler, N. Cancer and Climate Change. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, e519–e527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manisalidis, I.; Stavropoulou, E.; Stavropoulos, A.; Bezirtzoglou, E. Environmental and Health Impacts of Air Pollution: A Review. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Schelar, E. Pesticide Exposure and Child Neurodevelopment. Workplace Health Saf. 2012, 60, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Quezada, M.T.; Lucero, B.A.; Barr, D.B.; Steenland, K.; Levy, K.; Ryan, P.B.; Iglesias, V.; Alvarado, S.; Concha, C.; Rojas, E.; et al. Neurodevelopmental Effects in Children Associated with Exposure to Organophosphate Pesticides: A Systematic Review. Neurotoxicology 2013, 39, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Chang, C.H.; Tao, L.; Lu, C. Residential Exposure to Pesticide During Childhood and Childhood Cancers: A Meta-Analysis. Pediatrics 2015, 136, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarrete-Meneses, M.d.P.; Salas-Labadía, C.; Gómez-Chávez, F.; Pérez-Vera, P. Environmental Pollution and Risk of Childhood Cancer: A Scoping Review of Evidence from the Last Decade. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, S.; Morimoto, L.M.; Kang, A.Y.; Miller, M.D.; Wiemels, J.L.; Winestone, L.E.; Metayer, C. Pre- and Postnatal Exposures to Residential Pesticides and Survival of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Cancers 2025, 17, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamure, S.; Carles, C.; Aquereburu, Q.; Quittet, P.; Tchernonog, E.; Paul, F.; Jourdan, E.; Waultier, A.; Defez, C.; Belhadj, I.; et al. Association of Occupational Pesticide Exposure with Immunochemotherapy Response and Survival Among Patients with Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e192093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachek, C.M.; Miller, M.D.; Hsu, C.; Schiffman, J.D.; Sallan, S.; Metayer, C.; Dahl, G.V. Children’s Cancer and Environmental Exposures: Professional Attitudes and Practices. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2015, 37, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Rivera, L.T.; Sweetser, B.; Fuster-Soler, J.L.; Ramis, R.; López-Hernández, F.A.; Pérez-Martínez, A.; Ortega-García, J.A. Looking Towards 2030: Strengthening the Environmental Health in Childhood-Adolescent Cancer Survivor Programs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárceles-Álvarez, A.; Ortega-García, J.A.; López-Hernández, F.A.; Orozco-Llamas, M.; Espinosa-López, B.; Tobarra-Sánchez, E.; Alvarez, L. Spatial Clustering of Childhood Leukaemia with the Integration of the Paediatric Environmental History. Environ. Res. 2017, 156, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, J.; Hamilton, I.; Woodcock, J.; Williams, M.; Davies, M.; Wilkinson, P.; Haines, A. Health Benefits of Policies to Reduce Carbon Emissions. BMJ 2020, 368, l6758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).