Quality of Life and Psychological Distress Related to Fertility and Pregnancy in AYAs Treated for Gynecological Cancer: A Systematic Review

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

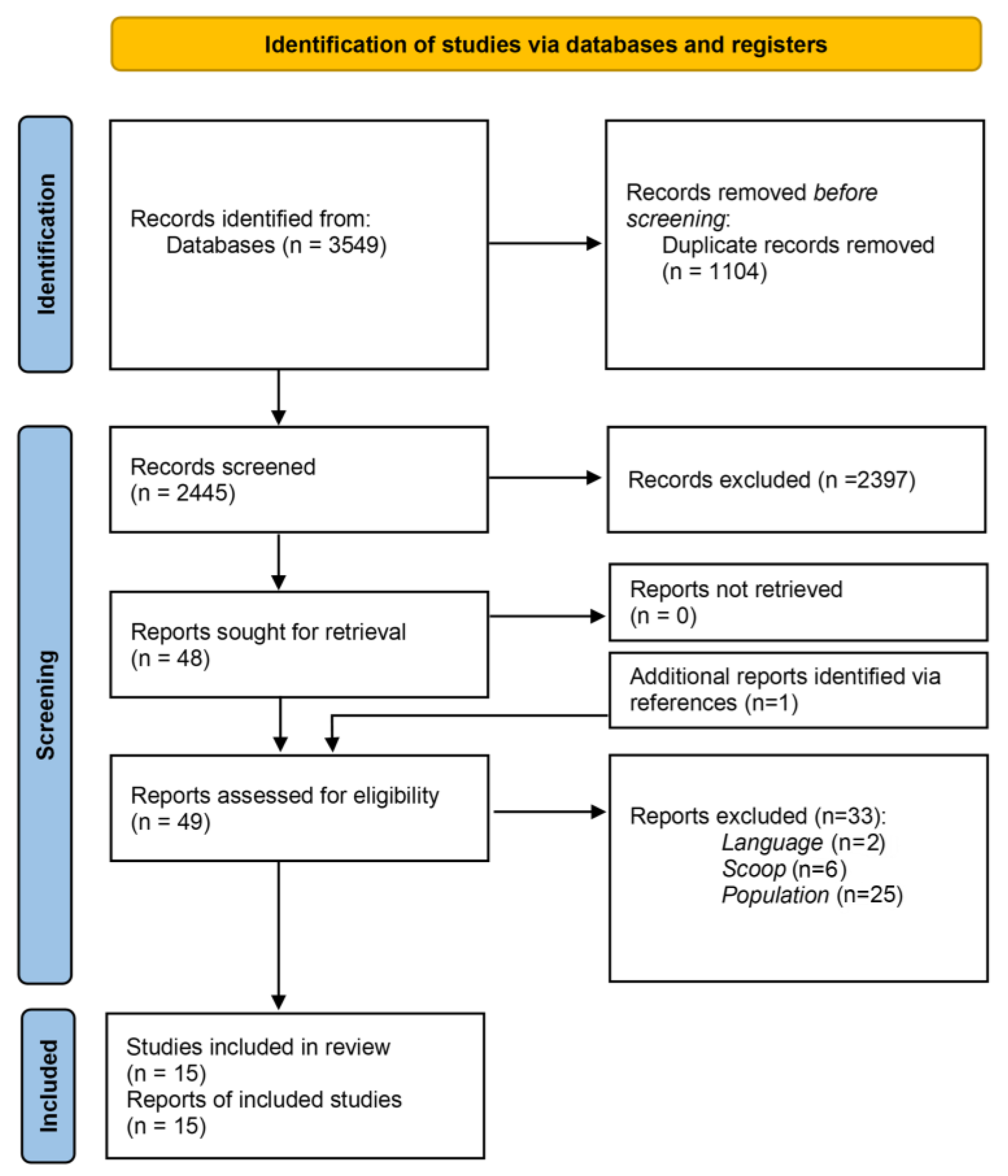

2.1. Search Strategy and Study Selection

2.2. Eligibility Criteria and Paper Selection

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Studies

3.1.1. Study Characteristics

3.1.2. Patient Characteristics

3.1.3. Quality Assessment

3.2. Key Thematic Findings

3.2.1. The Decision-Making Process

Attitudes Toward (Future) Fertility and Treatment Choice

3.2.2. Reflecting Back on Decisions Regarding FSS and FP

Decisional Regret

Knowledge and Attitudes Toward (Future) Fertility and Pregnancy

3.2.3. Reproductive Concerns and Psychological Distress

Baseline Characteristics

FSS vs. Non-FSS

Time Since Diagnosis

Comparison to Other AYAs with Cancer and Healthy Counterparts

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smith, A.W.; Seibel, N.L.; Lewis, D.R.; Albritton, K.H.; Blair, D.F.; Blanke, C.D.; Bleyer, W.A.; Freyer, D.R.; Geiger, A.M.; Hayes-Lattin, B.; et al. Next steps for adolescent and young adult oncology workshop: An update on progress and recommendations for the future. Cancer 2016, 122, 988–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holton, S.; Arts, G.D.; Stud, M.G.; Kirkman, M.; Rowe, H.; Fisher, J. The childbearing concerns and related information needs and preferences of women of reproductive age with a chronic, noncommunicable health condition: A systematic review. Womens Health Issues 2012, 22, e541–e552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobota, A.O.G. Fertility and parenthood issues in young female cancer patients—A systematic review. J. Cancer Surviv. 2014, 8, 707–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deshpande, N.A.; Braun, I.M.; Meyer, F.L. Impact of fertility preservation counseling and treatment on psychological outcomes among women with cancer: A systematic review. Cancer 2015, 121, 3938–3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morice, P.; Scambia, G.; Abu-Rustum, N.R.; Acien, M.; Arena, A.; Brucker, S.; Cheong, Y.; Collinet, P.; Fanfani, F.; Filippi, F.; et al. Fertility-sparing treatment and follow-up in patients with cervical cancer, ovarian cancer, and borderline ovarian tumours: Guidelines from ESGO, ESHRE, and ESGE. Lancet Oncol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, G.P.; Gonçalves, V.; Sehovic, I.; Bowman, M.L.; Reed, D.R. Quality of life in adolescent and young adult cancer patients: A systematic review of the literature. Patient Relat. Outcome Meas. 2015, 6, 19–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mean Age of Women at Childbirth and at Birth of First Child. 2024. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/product/page/TPS00017 (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- NKR. Incidentie Per Jaar, Baarmoederhalskanker. 15 February 2024. Available online: https://nkr-cijfers.iknl.nl/viewer/incidentie-per-jaar?language=nl_NL&viewerId=a41fc8bb-117b-43f2-a3c0-70be79827c7c (accessed on 3 October 2024).

- Letourneau, J.M.; Ebbel, E.E.; Katz, P.P.; Katz, A.; Ai, W.Z.; Chien, A.J.; Melisko, M.E.; Cedars, M.I.; Rosen, M.P. Pretreatment fertility counseling and fertility preservation improve quality of life in reproductive age women with cancer. Cancer 2012, 118, 1710–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trèves, R.; Grynberg, M.; le Parco, S.; Finet, A.; Poulain, M.; Fanchin, R. Female fertility preservation in cancer patients: An instrumental tool for the envisioning a postdisease life. Future Oncol. 2014, 10, 969–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, V.; Ferreira, P.L.; Saleh, M.; Tamargo, C.; Quinn, G.P. Perspectives of Young Women With Gynecologic Cancers on Fertility and Fertility Preservation: A Systematic Review. Oncologist 2022, 27, e251–e264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohara, T.; Kuji, S.; Takenaga, T.; Imai, H.; Endo, H.; Kanamori, R.; Takeuchi, J.; Nagasawa, Y.; Yokomichi, N.; Kondo, H.; et al. Current state of fertility preservation for adolescent and young adult patients with gynecological cancer. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 27, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Rosa, V.L.; Shah, M.; Icon, I.K.; Cerentini, T.M.; Icon, M.C.; Lin, L.-T.; Minona, P.; Tesarik, J. Quality of life and fertility preservation counseling for women with gynecological cancer: An integrated psychological and clinical perspective. J. Psychosom. Obs. Gynaecol. 2020, 41, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluye, P.; Hong, Q.N.; Bush, P.L.; Vedel, I. Opening-up the definition of systematic literature review: The plurality of worldviews, methodologies and methods for reviews and syntheses. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 73, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komatsu, H.; Yagasaki, K.; Shoda, R.; Chung, Y.; Iwata, T.; Sugiyama, J.; Fujii, T. Repair of the threatened feminine identity: Experience of women with cervical cancer undergoing fertility preservation surgery. Cancer Nurs. 2014, 37, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler-Manuel, S.A. Self-assessment of morbidity following radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. J. Obs. Gynaecol. 1999, 19, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, L.; Dogan-Ates, A.; Habbal, R.; Berkowitz, R.; Goldstein, D.P.; Bernstein, M.; Kluhsman, B.C.; Osann, K.; Newlands, E.; Seckl, M.J.; et al. Defining and Measuring Reproductive Concerns of Female Cancer Survivors. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2005, 34, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, L. Quality of life in long-term cervical cancer survivors. Gynecol. Oncol. 2005, 97, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, J.; Sonoda, Y.; Abu-Rustum, N.R. Reproductive concerns of women treated with radical trachelectomy for cervical cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2007, 105, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, J.; Sonoda, Y.; Baser, R.E.; Raviv, L.; Chi, D.S.; Barakat, R.R.; Iasonos, A.; Brown, C.L.; Abu-Rustum, N.R. A 2-year prospective study assessing the emotional, sexual, and quality of life concerns of women undergoing radical trachelectomy versus radical hysterectomy for treatment of early-stage cervical cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2010, 119, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattsson, E.; Einhorn, K.; Ljungman, L.; Sundström-Poromaa, I.; Stålberg, K.; Wikman, A. Women treated for gynaecological cancer during young adulthood—A mixed-methods study of perceived psychological distress and experiences of support from health care following end-of-treatment. Gynecol. Oncol. 2018, 149, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, J.; Letourneau, J.; Salem, W.; Cil, A.P.; Chan, S.-W.; Chen, L.-M.; Mitchell, R.P. Regret around fertility choices is decreased with pre-treatment counseling in gynecologic cancer patients. Cancer Surviv. 2017, 11, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sait, K.H. Conservative treatment of ovarian cancer. Safety, ovarian function preservation, reproductive ability, and emotional attitude of the patients in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2011, 32, 913–918. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Jiang, F.; Wang, X. Psychological State and Decision Perceptions of Male and Female Cancer Patients on Fertility Preservation. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 5723–5728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobota, A.; Ozakinci, G. Determinants of fertility issues experienced by young women diagnosed with breast or gynaecological cancer—A quantitative, cross-cultural study. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, J.; Raviv, L.; Applegarth, L.; Ford, JS.; Josephs, L.; Grill, E.; Sklar, C.; Sonoda, Y.; Baser, R.E.; Barakat, R.R. A cross-sectional study of the psychosexual impact of cancer-related infertility in women: Third-party reproductive assistance. J. Cancer Surviv. 2010, 4, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, K.; Shliakhtsitsava, K.; Natarajan, L.; Myers, E.; Dietz, A.; Gorman, J.; Martinex, M.; Whitcomb, B.; Su, H. Fertility Counseling Before Cancer Treatment and Subsequent Reproductive Concerns Among Female Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Survivors. Fertil. Couns. Concerns 2018, 125, 980–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentsen, L.; Pappot, H.; Hjerming, M.; Hanghøj, S. Thoughts about fertility among female adolescents and young adults with cancer: A qualitative study. Support. Care Cancer 2023, 31, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Standen, P.; Cohen, P.A.; Leung, Y.; Mohan, G.R.; Salfinger, S.; Tan, J.; Bulsara, C. Exploring Attitudes to Conception in Partners and Young Women with Gynecologic Cancers Treated by Fertility Sparing Surgery. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2020, 21, 2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlossman, J.; Vu, M.; Samborski, A.; Breit, K.; Thevenet-Morrison, K.; Wilbur, M. Identifying barriers individuals face in accessing fertility care after a gynecologic cancer diagnosis. Gynecol. Oncol. Rep. 2023, 49, 101267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Sergi, F.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, F.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A.; et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, S.; Perz, J.; Ussher, J.M.; Peate, M.; Anazodo, A. Systematic review of fertility-related psychological distress in cancer patients: Informing on an improved model of care. Psycho-Oncol. 2019, 28, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Berg, M.; Baysal, Ö.; Nelen, W.L.D.M.; Braat, D.D.M.; Beerendonk, C.C.M.; Hermens, R.P.M.G. Professionals’ barriers in female oncofertility care and strategies for improvement. Hum. Reprod. 2019, 34, 1074–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Anazodo, A.; Logan, S. Systematic review of fertility preservation patient decision aids for cancer patients. Psychooncology 2019, 28, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, M.; Lifford, K.J.; Wyld, L.; Armitage, F.; Ring, A.; Nettleship, A.; Collins, K.; Morgan, J.; Reed, M.W.R.; Holmes, G.R.; et al. Process evaluation of the Bridging the Age Gap in Breast Cancer decision support intervention cluster randomised trial. Trials 2021, 22, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, M.; van der Meij, E.; Bos, A.M.E.; Boshuizen, M.C.S.; Determann, D.; van Eekeren, R.R.J.P.; Lok, C.A.R.; Schaake, E.E.; Witteveen, P.O.; Wondergem, M.J.; et al. Development and testing of a tailored online fertility preservation decision aid for female cancer patients. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 1576–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NKR. NKR Cijfers—Incidentie Verdeling Per Stadium. 2024. Available online: https://nkr-cijfers.iknl.nl/viewer/incidentie-verdeling-per-stadium?language=nl_NL&viewerId=8fefcce3-449c-4cfb-95f4-31a6fe97e417 (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- NVOG. Fertiliteitsbehoud Bij Vrouwen Met Kanker. 2016. Available online: https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/fertiliteitsbehoud_bij_vrouwen_met_kanker/counseling_en_voorlichting/medische_aspecten_counseling_en_informat.html (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Flink, D.M.; Sheeder, J.; Kondapalli, L.A. A Review of the Oncology Patient’s Challenges for Utilizing Fertility Preservation Services. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2017, 6, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuurman, T.; Zilver, S.; Samuels, S.; Schats, W.; Amant, F.; van Trommel, N.; Lok, C. Fertility-Sparing Surgery in Gynecologic Cancer: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2021, 13, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnoth, C.; Godehardt, E.; Frank-Herrmann, P.; Friol, K.; Tigges, J.; Freundl, G. Definition and prevalence of subfertility and infertility. Hum. Reprod. 2005, 20, 1144–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louwé, L.A.; Stiggelbout, A.M.; Overbeek, A.; Hilders, C.G.J.M.; van den Berg, M.H.; Wendel, E.; van Dulmen-den Broeder, E.; ter Kuile, M.M. Factors associated with frequency of discussion of or referral for counselling about fertility issues in female cancer patients. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2018, 27, e12602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, S.; Avila, J.C.; Mutambudzi, M.; Russell, H.; Kirchhoff, A.C.; Schwartz, C.L. Mental distress and health care use among survivors of adolescent and young adult cancer: A cross-sectional analysis of the National Health Interview Survey. Cancer 2017, 123, 869–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study, Origin | Aim | Inclusion Criteria, Recruitment Sites, Study Period | Type of Study, Study Design, Measurements | Sample Size, Age at Diagnosis (Mean and Range), Parity at Diagnosis | Fertility Counseling, FP/FSS | Response Rate, Time Since Diagnosis (Mean) | Relevant Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bentsen et al. 2023 Denmark [30] | Exploring thoughts about fertility | AYAs with cancer 18–39 years old at recruitment Recruitment in one hospital 2020–2021 | Qualitative Cross-sectional Semi-structured interviews | n = 12; Ovarian cancer n = 3/12 (25%) age 28 (20–35) parity at diagnosis unknown | Counseling (1/3) (33%), FSS 33% | Unknown Unknown (4 AYAs still received cancer therapy) | Theme identification: • Keeping hope on future children • Participants felt time pressure to choose for fertility preservation and being forced to wait for pregnancy due to treatment • The women faced existential and ethical choices about survival and family formation • Loss of control over the body and treatment |

| Carter et al. 2007, USA [21] | Exploring reproductive and emotional concerns associated with FSS | Cervical cancer patients 18 and 45 years old at diagnosis, with a pregnancy wish. Planned for radical trachelectomy Recruitment in one hospital 2004–2006 | Qualitative Prospective: Pre-operative, after 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months post-surgery Reproductive concerns: Self-developed open-ended questions | n = 29 age 32 (23–40) parity at diagnosis unknown | Fertility counseling: (100%) FSS: (100%) | Pre-operative 83% 3-months post-surgery 68% 6-months post-surgery 82% N/A | • Women stated during the pre-operative assessment that they were concerned about their ability to conceive and maintaining a pregnancy • Women stated they felt time-pressured because of their age, and limited time for conception • Several women reported concerns about the impact of cancer history and treatment on their future baby |

| Carter et al. 2010, USA [28] | Exploring emotions, reproductive concerns and QoL Determining whether knowledge of, and access to third-party (surrogacy, egg donation) reproduction influences psychosocial outcomes | 18–49 years old at recruitment; (1) AYAs with gynecologic cancer (2) BMT/SCT survivors (3) Control group: non cancer patients, wait-list for egg donation (1,2,3) Did not start or has completed childbearing Recruitment in two centers 2006–2009 | Quantitative Cross-sectional Reproductive concerns: (RCS) Depression: CES-D Distress: IES (Validated questionnaires) Self-developed questionnaires on perception of third-party parenting, reproductive informational needs, health-related concerns | n = 172 GYN-survivors n = 51 (30%), age 35 (21–46) BMT/SCT = 71 (41%), age 23 (4–45) non-cancer Infertile control group = 50 (29%) parity at diagnosis unknown | Counseling (% unknown), FP none | Gynecologic 89%, BMT/SCT: 81%, Control group 74% GYN survivors: 4 years and BMT/SCT survivors: 10 years | • No significant differences between mood, reproductive concerns, and mental health QOL were identified between infertile groups (cancer vs. non-cancer) • Cancer survivors (cervical + BMT/SCT) with a perceived need for more information on reproductive options had significantly higher depression and avoidance scores than women reporting no need for more information about reproductive options • Women with infertility without cancer history had significantly higher distress levels than women with gynecological cancer history • 55% of GYN-survivors had the feeling they did not have options for Assisted Reproductive Technique. • 71% of GYN-survivors rated being a parent as most important in their lives |

| Carter, Sonoda 2010, USA [22] | Exploring emotional functioning, reproductive concerns and QOL | AYAs with cervical cancer with a choice for RT or RH. Recruitment in clinics 2004–2008 | Quantitative Prospective Attitudes toward treatment choice and the decision-making process: exploratory items Reproductive concerns: Exploratory items | n = 71 RT group n = 43 (61%) age 33 RH group n = 28 (39%) age 38 nulliparous RT group n = 36 (84%), RH group n = 12 (43%) | Counseling (% unknown) FSS 61% | Unknown N/A | • 48% of RT vs. 8.6% of RH patients stated they have had adequate time to complete childbearing and stated this was one of the factors for their treatment decision • Women in RT group were younger than women in the RH group (mean age 33 vs. 38) • Fertility was for 98% vs. 46% in RT and RH group one of the most important factors for their treatment decision • Only the RT group was asked about their concerns on: 1. conceiving a baby in the future. Pre-operatively 91% of the AYAs indicated concerns. This percentage decreased to 73% after two years • 2. Feeling successful at conceiving in the future on a scale from 0–100% Pre-operatively, the mean rating was 62% (25–100) decreasing to 55% after 1 year and restoring to 60% after 2 years • After two years 21% was attempting conception, 15% had successfully conceived, and 9% had achieved a successful pregnancy • Only 18% of AYAs had spoken to a fertility specialist within the first two years after surgery |

| Chan et al. 2017, USA [24] | Determining the effect of FSS on regret, and characterize patients with highest risk of regret | Gynecological cancer patients, 18 to 40 years old at diagnosis Recruitment via a state Registry 2010–2013 | Quantitative Cross-sectional Questionnaires: FP (yes/no) Decisional regret: DRS (Validated questionnaire) | n = 470, age 34 (18–40) Cervical = 228 (49%) Ovarian = 125 (26%) Endometrial = 117 (25%) nulliparous n = 146 (31%) | Fertility counseling (46%) FP/FSS (39%) Self-reported | 79% 11 years | • All AYAs were eligible for FSS. Only 46% recalled receiving fertility counseling • After adjusting for age, recalling (satisfactory) counseling and receiving FSS were associated with lower regret • Half of the women desired more children after treatment • Desire for children at time of diagnosis was associated with increased decisional regret (p < 0.001) |

| Chen et al. 2022, China [26] | Exploring emotional state and perceptions on FP/FSS decisions | Diagnosed with gynecological cancer or a benign abnormality on the ovary >18 years old Counseled for FP Recruitment in one hospital 2019–2021 | Quantitative Cross-sectional Decisional conflict: DCS Decisional Regret: DRS (Validated questionnaires) | n = 33 Female = 16 (48%), age 34 (range unknown) parity at diagnosis unknown | Fertility counseling (100%) FP/FSS (100%) | 80% Directly after fertility preservation | • Decisional conflict score on FP/FSS decision was high in women with gynecological cancer • Women felt conflicted between chances on survival and chances on preservation of fertility • Women felt supported by others • DRS-score for decision on FP/FSS was low |

| Komatsu 2014, Japan [17] | Exploring the experience of AYAs on FP/FSS | AYAs with cervical cancer treated with radical trachelectomy Recruitment in one hospital 2011–2012 | Qualitative Cross-sectional, Semi-structured Interview: Perceptions on FP/FSS Perceptions on conception and childbearing after FSS | n = 15 age 32 (25–38) nulliparous n = 14 (93%) | Fertility counseling (100%) FP/FSS (100%) | Unknown 2 years (median) | • n = 3 (20%) had one or more child(ren) after treatment. Themes: • The possibility of the uterus being removed caused a lot of anxiety • FP/FSS repairs the threatened feminine identity in women with cervical cancer • FP/FSS does not simply mean childbearing, maintaining the ability to conceive is significant • Some women imagined their childless life as the worst case scenario |

| Mattsson et al. 2018, Sweden [23] | Determining the prevalence and predictors of fertility-related distress | Patients with gynecological cancer between 2008–2016 Recruitment from the national cancer registry 2016 -unknown | Quantitative Cross-sectional Cancer-related distress (Non-validated self-developed questionnaire) | n = 337 age 33 (range 19–39) Cervical cancer n = 224 (66%) Other n = 112 (33%) parity at diagnosis unknown | Fertility counseling (% Unknown) FP/FSS (% Unknown) | 52% 3 Years | • n = 121 (36%) of the women did not have children at time of survey • n = 79 (27%) of the women experienced fertility concerns • Cancer related distress was more common in women without children (90%) than with children (82%) p = 0.046 • Women stated that support groups with other AYA cancer patients were lacking |

| Sait 2011, Saudi-Arabia [25] | Exploring emotional attitude on fertility and pregnancy after treatment | AYAs with ovarian cancer treated with FSS between 2000–2010 Recruitment in one hospital Unknown | Quantitative Cross-sectional Phone call survey 3 questions on emotional attitudes extracted from a validated questionnaire | n = 23 age 22 (4–35) parity at diagnosis unknown | Fertility counseling (100%) FP/FSS (100%) | 59% Unknown | • n = 35 (90%) of the women did not have children at time of survey • Almost half of the women stated that the chosen treatment will have an impact on the desire to have children in the future n = 10 (44%) • Half of the women were afraid that the received FSS would damage their reproductive potential n = 12 (52%) • Few women were concerned that FSS would have an effect on their (future) offspring n = 2 (9%) |

| Schlossman et al. 2023, USA [32] | Exploring barriers of women toward fertility care after treatment and exploring experiences around fertility | Treated for gynecological cancer and still in follow up Recruitment from an academic state hospital 2012–2022 | Mixed methods Cross-sectional survey and semi-structured interviews Self-developed questionnaire on the effect of cancer diagnosis and counseling on childbearing and fertility plans | Questionnaire study: n = 55 age 32 Cervical n = 23 Ovarian n = 20 Endometrial n = 12 Interview study: n = 20 parity at diagnosis unknown, n = 26 (47%) had never been pregnant before diagnosis | Fertility counseling (80%) FP/FSS (53%) | 24% Unknown | • n = 40 (73%) was considering (more) children in the future • Half of the AYAs reported that their family planning goals had not changed due to treatment, one third said it had drastically changed • AYAs who had not undergone fertility preservation stated that this was due to not wanting to delay treatment (49%), feeling to emotionally burdened (18%), or having received inadequate counseling (14%) • There was no statistical difference between FP/FSS and no FP/FSS in terms of age, having a partner at diagnosis and the quality of counseling • Women who had children at time of diagnosis were 72% less likely to undergo FP compared to women who did not have children • During the interviews, 80% of women stated they had not met their family planning goals yet • Women who did not seek fertility care, said this was because of: inadequate counseling (60%), lack of time (60%), economic constraints (55%) and cancer treatment prioritization (55%) • Multiple AYAs were frustrated with the lack of AYA support groups |

| Sobota and Ozakinci, 2018, United Kingdom, Poland [27] | Determining the associated factors of distress related to reproductive issues and assessing potential impact of socio-cultural background | History of gynecological- or breast cancer Recruitment via multiple outpatient clinics Unknown | Quantitative Cross-sectional survey Psychological wellbeing: IES-R Illness perceptions: Brief-IPQ Value of Children: VOC (Validated questionnaires) Decisional regret: (1 Unvalidated question) Prediction model: Fertility-related distress | n = 164 age 35 (19–46) Gynecological = 129 (79%) parity at diagnosis unknown | Fertility counseling (% Unknown) FP/FSS (26%) | 47% 3 years | • n = 80 (49%) of the women was nulliparous at time of survey • Strongest associated factors for fertility-related distress: Treatment-related regret (p < 0.05) Emotional response to cancer diagnosis (p < 0.01) Polish background compared to British background (p < 0.01) • Desire for more children was correlated with treatment-related regret However, the desire for more children was higher in the group of women with a Polish background and background therefore seen as an indirect effect |

| Standen et al. 2020, Australia [31] | Exploring attitudes to conception after FSS | Treated for gynecological cancer with FSS between 2005–2016 Recruitment from a tumour board database Unknown | Qualitative Semi-structured phone call interview Theme development: perceptions and knowledge of FSS, and on fertility services | n = 14 age 33 (range unknown) Cervical n = 6 Endometrial n = 3 Ovarian n = 5 (and their partners) nulliparous n = 7 (50%) | Fertility counseling (100%) FP/FSS (100%) | 30% Unknown | • ±50% of the women had not considered children at time of diagnosis and were forced to do so • One woman had conceived a child after treatment while four women attempted IVF • Women who underwent involuntary secondary surgery with complete removal of the uterus or ovaries expressed regret and advised others only to do this if childbearing is completed • Cancer diagnosis and possible infertility had major impact on (future) relationships |

| Wenzel et al. 2005, USA [19] Wenzel, de Alba 2005, USA [20] | Exploring psychosocial and reproductive concerns, and QoL | Treated for gynecological cancer or lymphoma 5–10 years earlier compared to healthy controls Recruitment from two cancer registry programs Unknown | Quantitative Cross-sectional Phone call-or email survey Quality of Life: QOL-CS Psychological distress: IES Reproductive concerns: Self-developed scale Self-reported infertility | n = 379 Cervical n = 51 (31%), age 37 (range unknown) GTT n = 111 (69%) age 33 (range unknown) age-matched controls = 148 Parity unknown | Fertility counseling (% Unknown) FP/FSS (% Unknown) | Cervical: 88% GTT: 95% Cervical cancer group: 8 years GTT group: 7 years | • AYAs with cervical cancer reported satisfactory QoL • Mental and physical state did not significantly differ from healthy controls • Among cancer survivors, reproductive concerns were associated with lower QoL (p < 0.001), poorer physical and mental health • Together with less social support and having physical gynecological problems, reproductive concerns were accounted for 63% of the variance in QoL • More reproductive concerns were reported by AYAs with cancer compared to healthy controls (p < 0.0001) • Reproductive concerns were associated with the inability to have children (p < 0.001) • Self-reported infertile women had poorer mental health (p < 0.05), more cancer-specific distress (p < 0.01), and lower overall (p < 0.001), physical (p < 0.01), and psychological (p < 0.001) well-being than women who were fertile |

| Young et al. 2019, USA [29] | Exploring the association between cancer type and treatment with reproductive concerns | 15–35 years old at diagnosis and completed primary treatment Recruitment from national cancer registries 2015–2017 | Quantitative Cross-sectional Survey at study baseline and serial online surveys over 18 months Reproductive concerns: RCAC | n = 747 Gynecological n = 57 (8%) mean age unknown (15–35) nulliparous n = 559 (75%) | Fertility counseling (19%) FP/FSS (12%) | Unknown >5 years (64%) 2–5 years (24.5%) <2 years (11.4%) | • No significant differences in reproductive concerns were found between cancer types • 44% of the participants had moderate to high reproductive concerns • Reproductive concerns were similar between the group of women receiving counseling and FP/FSS, and receiving counseling without FP/FSS • Higher reproductive concerns were associated with not having children at diagnosis (p < 0.001) and at time of questionnaire (p < 0.001), younger age (p < 0.001), not having a relationship at time of questionnaire (p < 0.001), and lower income (p = 0.03) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stroeken, Y.; Hendriks, F.; Beltman, J.; ter Kuile, M. Quality of Life and Psychological Distress Related to Fertility and Pregnancy in AYAs Treated for Gynecological Cancer: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2024, 16, 3456. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16203456

Stroeken Y, Hendriks F, Beltman J, ter Kuile M. Quality of Life and Psychological Distress Related to Fertility and Pregnancy in AYAs Treated for Gynecological Cancer: A Systematic Review. Cancers. 2024; 16(20):3456. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16203456

Chicago/Turabian StyleStroeken, Yaël, Florine Hendriks, Jogchum Beltman, and Moniek ter Kuile. 2024. "Quality of Life and Psychological Distress Related to Fertility and Pregnancy in AYAs Treated for Gynecological Cancer: A Systematic Review" Cancers 16, no. 20: 3456. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16203456

APA StyleStroeken, Y., Hendriks, F., Beltman, J., & ter Kuile, M. (2024). Quality of Life and Psychological Distress Related to Fertility and Pregnancy in AYAs Treated for Gynecological Cancer: A Systematic Review. Cancers, 16(20), 3456. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16203456