Fractionated Stereotactic Intensity-Modulated Radiotherapy for Large Brain Metastases: Comprehensive Analyses of Dose–Volume Predictors of Radiation-Induced Brain Necrosis

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patients

2.2. Radiotherapy Details

2.3. Patient Follow-Ups, Endpoints, and Dose–Volume Parameters

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

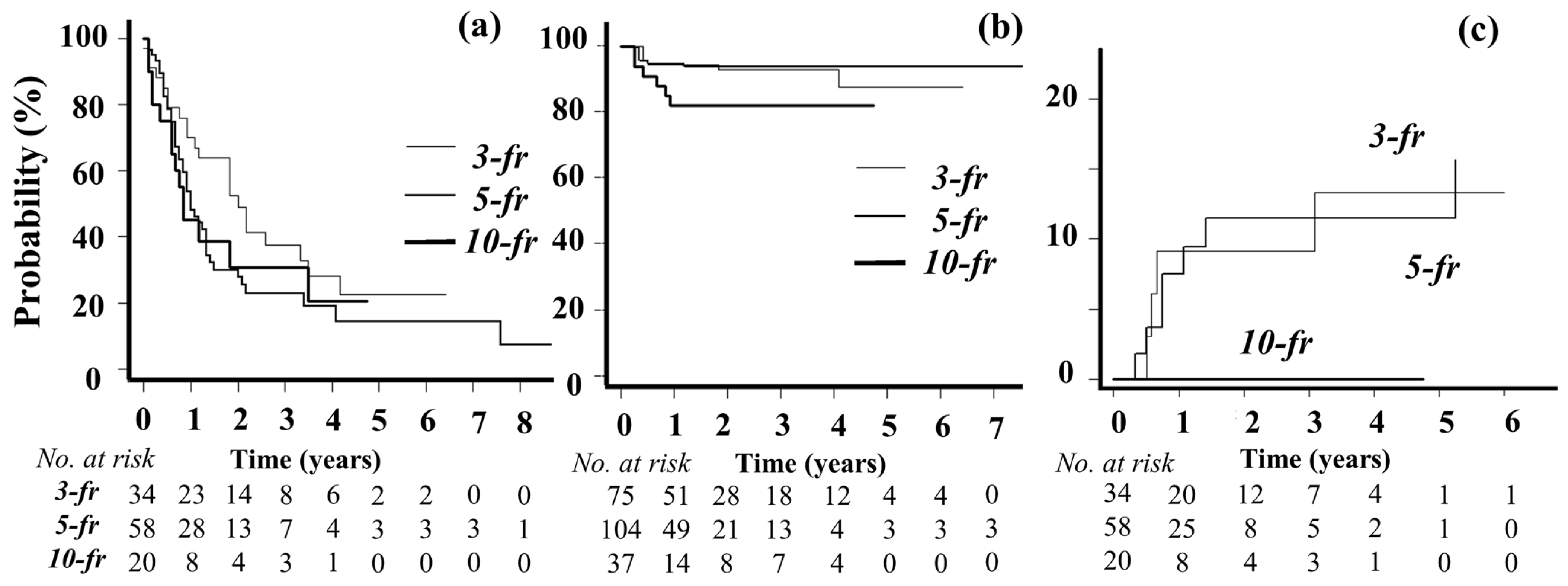

3.1. Patient Characteristics, Treatment Details, and Outcomes

3.2. Toxicities

3.3. Multivariate Analyses of BN

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Burney, I.A.; Aal Hamad, A.H.; Hashmi, S.F.A.; Ahmad, N.; Pervez, N. Evolution of the management of brain metastases: A bibliometric analysis. Cancers 2023, 15, 5570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiff, D.; Messersmith, H.; Brastianos, P.K.; Brown, P.D.; Burri, S.; Dunn, I.F.; Gaspar, L.E.; Gondi, V.; Jordan, J.T.; Maues, J.; et al. Radiation therapy for brain metastases: Asco guideline endorsement of astro guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 2271–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benkhaled, S.; Schiappacasse, L.; Awde, A.; Kinj, R. Stereotactic radiosurgery and stereotactic fractionated radiotherapy in the management of brain metastases. Cancers 2024, 16, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaios, E.J.; Winter, S.F.; Shih, H.A.; Dietrich, J.; Peters, K.B.; Floyd, S.R.; Kirkpatrick, J.P.; Reitman, Z.J. Novel mechanisms and future opportunities for the management of radiation necrosis in patients treated for brain metastases in the era of immunotherapy. Cancers 2023, 15, 2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milano, M.T.; Grimm, J.; Niemierko, A.; Soltys, S.G.; Moiseenko, V.; Redmond, K.J.; Yorke, E.; Sahgal, A.; Xue, J.; Mahadevan, A.; et al. Single- and multifraction stereotactic radiosurgery dose/volume tolerances of the brain. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2021, 110, 68–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouzen, J.A.; Petoukhova, A.L.; Broekman, M.L.D.; Fiocco, M.; Fisscher, U.J.; Franssen, J.H.; Gadellaa-van Hooijdonk, C.G.M.; Kerkhof, M.; Kiderlen, M.; Mast, M.E.; et al. SAFESTEREO: Phase II randomized trial to compare stereotactic radiosurgery with fractionated stereotactic radiosurgery for brain metastases. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmond, K.J.; Gui, C.; Benedict, S.; Milano, M.T.; Grimm, J.; Vargo, J.A.; Soltys, S.G.; Yorke, E.; Jackson, A.; El Naqa, I.; et al. Tumor control probability of radiosurgery and fractionated stereotactic radiosurgery for brain metastases. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2021, 110, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murai, T.; Ogino, H.; Manabe, Y.; Iwabuchi, M.; Okumura, T.; Matsushita, Y.; Tsuji, Y.; Suzuki, H.; Shibamoto, Y. Fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy using CyberKnife for the treatment of large brain metastases: A dose escalation study. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 26, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehrer, E.J.; Peterson, J.L.; Zaorsky, N.G.; Brown, P.D.; Sahgal, A.; Chiang, V.L.; Chao, S.T.; Sheehan, J.P.; Trifiletti, D.M. Single versus multifraction stereotactic radiosurgery for large brain metastases: An international meta-analysis of 24 trials. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2019, 103, 618–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondi, V.; Bauman, G.; Bradfield, L.; Burri, S.H.; Cabrera, A.R.; Cunningham, D.A.; Eaton, B.R.; Hattangadi-Gluth, J.A.; Kim, M.M.; Kotecha, R.; et al. Radiation therapy for brain metastases: An ASTRO clinical practice guideline. Pract. Radiat. Oncol. 2022, 12, 265–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogelbaum, M.A.; Brown, P.D.; Messersmith, H.; Brastianos, P.K.; Burri, S.; Cahill, D.; Dunn, I.F.; Gaspar, L.E.; Gatson, N.T.N.; Gondi, V.; et al. Treatment for brain metastases: ASCO-SNO-ASTRO guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 492–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladbury, C.; Pennock, M.; Yilmaz, T.; Ankrah, N.K.; Andraos, T.; Gogineni, E.; Kim, G.G.; Gibbs, I.; Shih, H.A.; Hattangadi-Gluth, J.; et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery in the management of brain metastases: A case-based radiosurgery society practice guideline. Adv. Radiat. Oncol. 2024, 9, 101402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmerman, R. A Story of hypofractionation and the table on the wall. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2022, 112, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korytko, T.; Radivoyevitch, T.; Colussi, V.; Wessels, B.W.; Pillai, K.; Maciunas, R.J.; Einstein, D.B. 12 Gy gamma knife radiosurgical volume is a predictor for radiation necrosis in non-AVM intracranial tumors. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2006, 64, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellsworth, S.G.; van Rossum, P.S.N.; Mohan, R.; Lin, S.H.; Grassberger, C.; Hobbs, B. Declarations of independence: How embedded multicollinearity errors affect dosimetric and other complex analyses in radiation oncology. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2023, 117, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahiri, A.; Maji, A.; Potdar, P.D.; Singh, N.; Parikh, P.; Bisht, B.; Mukherjee, A.; Paul, M.K. Lung cancer immunotherapy: Progress, pitfalls, and promises. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.A.; Lennerz, J.; Johnson, M.L.; Gordan, L.N.; Dumanois, R.H.; Quagliata, L.; Ritterhouse, L.L.; Cappuzzo, F.; Wang, B.; Xue, M.; et al. Compromised outcomes in stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer with actionable mutations initially treated without tyrosine kinase inhibitors: A retrospective analysis of real-world data. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2024, 20, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wespiser, M.; Swalduz, A.; Perol, M. Treatment sequences in EGFR mutant advanced NSCLC. Lung Cancer 2024, 194, 107895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Jiang, S.; Shi, Y. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors for solid tumors in the past 20 years (2001–2020). J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modi, S.; Jacot, W.; Yamashita, T.; Sohn, J.; Vidal, M.; Tokunaga, E.; Tsurutani, J.; Ueno, N.T.; Prat, A.; Chae, Y.S.; et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in previously treated HER2-low advanced breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolchok, J.D.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Rutkowski, P.; Cowey, C.L.; Schadendorf, D.; Wagstaff, J.; Queirolo, P.; Dummer, R.; Butler, M.O.; Hill, A.G.; et al. Final, 10-year outcomes with nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murai, T.; Hayashi, A.; Manabe, Y.; Sugie, C.; Takaoka, T.; Yanagi, T.; Oguri, T.; Matsuo, M.; Mori, Y.; Shibamoto, Y. Efficacy of stereotactic radiotherapy for brain metastases using dynamic jaws technology in the helical tomotherapy system. Br. J. Radiol. 2016, 89, 20160374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibamoto, Y.; Miyakawa, A.; Otsuka, S.; Iwata, H. Radiobiology of hypofractionated stereotactic radiotherapy: What are the optimal fractionation schedules? J. Radiat. Res. 2016, 57 (Suppl. 1), i76–i82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhauer, E.A.; Therasse, P.; Bogaerts, J.; Schwartz, L.H.; Sargent, D.; Ford, R.; Dancey, J.; Arbuck, S.; Gwyther, S.; Mooney, M.; et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur. J. Cancer 2009, 45, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsura, M.; Sato, J.; Akahane, M.; Furuta, T.; Mori, H.; Abe, O. Recognizing radiation-induced changes in the central nervous system: Where to look and what to look for. Radiographics 2021, 41, 224–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, Z.S.; Halima, A.; Broughman, J.R.; Smile, T.D.; Tom, M.C.; Murphy, E.S.; Suh, J.H.; Lo, S.S.; Barnett, G.H.; Wu, G.; et al. Radiation necrosis or tumor progression? A review of the radiographic modalities used in the diagnosis of cerebral radiation necrosis. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2023, 161, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urso, L.; Bonatto, E.; Nieri, A.; Castello, A.; Maffione, A.M.; Marzola, M.C.; Cittanti, C.; Bartolomei, M.; Panareo, S.; Mansi, L.; et al. The role of molecular imaging in patients with brain metastases: A literature review. Cancers 2023, 15, 2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murai, T.; Shibamoto, Y.; Manabe, Y.; Murata, R.; Sugie, C.; Hayashi, A.; Ito, H.; Miyoshi, Y. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy using static ports of tomotherapy (TomoDirect): Comparison with the TomoHelical mode. Radiat. Oncol. 2013, 8, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrell, F.E., Jr.; Lee, K.L.; Mark, D.B. Multivariable prognostic models: Issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat. Med. 1996, 15, 361–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, R.D.; Ensor, J.; Snell, K.I.E.; Harrell, F.E., Jr.; Martin, G.P.; Reitsma, J.B.; Moons, K.G.M.; Collins, G.; van Smeden, M. Calculating the sample size required for developing a clinical prediction model. BMJ 2020, 368, m441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Smeden, M.; Moons, K.G.; de Groot, J.A.; Collins, G.S.; Altman, D.G.; Eijkemans, M.J.; Reitsma, J.B. Sample size for binary logistic prediction models: Beyond events per variable criteria. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2019, 28, 2455–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2013, 48, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, G.S.; Ogundimu, E.O.; Cook, J.A.; Manach, Y.L.; Altman, D.G. Quantifying the impact of different approaches for handling continuous predictors on the performance of a prognostic model. Stat. Med. 2016, 35, 4124–4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Dhiman, P.; Qi, C.; Bullock, G.; van Smeden, M.; Riley, R.D.; Collins, G.S. Poor handling of continuous predictors in clinical prediction models using logistic regression: A systematic review. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2023, 161, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loganadane, G.; Dhermain, F.; Louvel, G.; Kauv, P.; Deutsch, E.; Le Pechoux, C.; Levy, A. Brain radiation necrosis: Current management with a focus on non-small cell lung cancer patients. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paz-Ares, L.; Luft, A.; Vicente, D.; Tafreshi, A.; Gumus, M.; Mazieres, J.; Hermes, B.; Cay Senler, F.; Csoszi, T.; Fulop, A.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy for squamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2040–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, M.; Serizawa, T.; Sato, Y.; Higuchi, Y.; Kasuya, H. Stereotactic radiosurgery results for patients with 5–10 versus 11–20 brain metastases: A retrospective cohort study combining 2 databases totaling 2319 patients. World Neurosurg. 2021, 146, e479–e491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehrer, E.J.; McGee, H.M.; Peterson, J.L.; Vallow, L.; Ruiz-Garcia, H.; Zaorsky, N.G.; Sharma, S.; Trifiletti, D.M. Stereotactic radiosurgery and immune checkpoint inhibitors in the management of brain metastases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, C.; Grimm, J.; Kleinberg, L.R.; Zaki, P.; Spoleti, N.; Mukherjee, D.; Bettegowda, C.; Lim, M.; Redmond, K.J. A dose-response model of local tumor control probability after stereotactic radiosurgery for brain metastases resection cavities. Adv. Radiat. Oncol. 2020, 5, 840–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutschenritter, T.; Venur, V.A.; Combs, S.E.; Vellayappan, B.; Patel, A.P.; Foote, M.; Redmond, K.J.; Wang, T.J.C.; Sahgal, A.; Chao, S.T.; et al. The judicious use of stereotactic radiosurgery and hypofractionated stereotactic radiotherapy in the management of large brain metastases. Cancers 2020, 13, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minniti, G.; Scaringi, C.; Paolini, S.; Lanzetta, G.; Romano, A.; Cicone, F.; Osti, M.; Enrici, R.M.; Esposito, V. Single-fraction versus multifraction (3 × 9 gy) stereotactic radiosurgery for large (>2 cm) brain metastases: A comparative analysis of local control and risk of radiation-induced brain necrosis. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2016, 95, 1142–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, R.; Ayan, A.S.; Jain, S.; Klamer, B.G.; Perlow, H.K.; Zoller, W.; Blakaj, D.M.; Beyer, S.; Grecula, J.; Arnett, A.; et al. Dose-volume tolerance of the brain and predictors of radiation necrosis after 3-fraction radiosurgery for brain metastases: A large single-institutional analysis. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2024, 118, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, H.K.; Sato, H.; Seto, K.; Torikai, K.; Suzuki, Y.; Saitoh, J.; Noda, S.E.; Nakano, T. Five-fraction CyberKnife radiotherapy for large brain metastases in critical areas: Impact on the surrounding brain volumes circumscribed with a single dose equivalent of 14 Gy (V14) to avoid radiation necrosis. J. Radiat. Res. 2014, 55, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andruska, N.; Kennedy, W.R.; Bonestroo, L.; Anderson, R.; Huang, Y.; Robinson, C.G.; Abraham, C.; Tsien, C.; Knutson, N.; Rich, K.M.; et al. Dosimetric predictors of symptomatic radiation necrosis after five-fraction radiosurgery for brain metastases. Radiother. Oncol. 2021, 156, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constanzo, J.; Faget, J.; Ursino, C.; Badie, C.; Pouget, J.P. Radiation-induced immunity and toxicities: The versatility of the cGAS-STING pathway. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 680503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvestrini, V.; Greco, C.; Guerini, A.E.; Longo, S.; Nardone, V.; Boldrini, L.; Desideri, I.; De Felice, F. The role of feature-based radiomics for predicting response and radiation injury after stereotactic radiation therapy for brain metastases: A critical review by the young group of the Italian association of radiotherapy and clinical oncology (yAIRO). Transl. Oncol. 2022, 15, 101275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Karlsen, M.; Karlberg, A.M.; Redalen, K.R. Hypoxia imaging and theranostic potential of [64Cu][Cu(ATSM)] and ionic Cu(II) salts: A review of current evidence and discussion of the retention mechanisms. EJNMMI Res. 2020, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Biological Equivalent Dose in 2 Gy/fr | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fr No. | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 | 35 | 40 | 45 | 50 | 55 | 60 | |

| Dose (Gy) | 3 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 14 | 16 | 17 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 23 | 24 |

| 5 | 10 | 14 | 15 | 17 | 20 | 21 | 23 | 25 | 27 | 28 | 30 | |

| 10 | 12 | 16 | 20 | 23 | 26 | 28 | 31 | 33 | 35 | 37 | 40 | |

| Treatment Protocol | 30 Gy/3 fr | 35 Gy/5 fr | 37.5 Gy/5 fr | 40 Gy/10 fr | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient number | 34 | 30 | 28 | 20 | |

| Age | (mean ± SD) | 67.1 ± 10.0 | 67.4 ± 9.6 | 63.6 ± 9.3 | 65.2 ± 16.2 |

| <60, ≥60 <70, ≥70 | 13, 7, 15 | 12, 9, 13 | 17, 8, 9 | 16, 6, 5 | |

| Sex (female, male) | 8, 26 | 14, 16 | 13, 15 | 8, 12 | |

| Extracranial disease (+, −) | 31, 3 | 28, 2 | 28, 0 | 19, 1 | |

| Performance status (0, 1, 2) | 6, 25, 3 | 6, 21, 3 | 3, 21, 4 | 6, 7, 7 | |

| Primary cancer (patient No.) | |||||

| Lung cancer | 29 | 20 | 17 | 10 | |

| GI cancer | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | |

| Breast cancer | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | |

| Renal cancer | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | |

| Sarcoma | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | |

| Urothelial cancer | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | |

| Others | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | |

| Total BM No. | 75 | 57 | 47 | 37 | |

| Median (range)/patient | 1.5 (1–9) | 1 (1–8) | 1 (1–5) | 1 (1–6) | |

| single, multiple | 17, 17 | 19, 11 | 19, 9 | 13, 7 | |

| Total PTV (cc) (mean ± SD, median) | 4.3 ± 4.7, 3.2 | 7.1 ± 3.7, 6.4 | 24.0 ± 17.5, 20.2 | 25.9 ± 13.0, 24.3 | |

| Prescribed dose (Gy) * | 30 (18–30) | 35 (30–35) | 37.5 (30–37.5) | 40 (36–40) | |

| D95%(Gy) (mean ± SD) | 29.2 ± 1.9 | 33.3 ± 2.1 | 35.3 ± 3.0 | 37.7 ± 1.7 | |

| D98%(Gy) (mean ± SD) | 28.7 ±1.9 | 32.7 ± 2.2 | 34.6 ± 3.0 | 37.0 ± 1.9 | |

| D2%(Gy) (mean ± SD) | 32.1 ± 2.1 | 37.0 ± 2.6 | 38.6 ± 3.5 | 41.5 ± 2.2 | |

| CI (mean ± SD) | 3.05 ± 7.13 | 1.40 ± 1.27 | 2.34 ± 4.37 | 1.16 ± 0.63 | |

| UI (mean ± SD) | 1.09 ± 0.05 | 1.11 ± 0.09 | 1.09 ± 0.08 | 1.09 ± 0.06 | |

| ≥Grade 1 Brain Necrosis | |||

| AOR | (95% Confidence Interval) | p-Value | |

| PTV (cc) | 0.98 | (0.93–1.04) | 0.52 |

| V60EQD2 (cc) | 1.07 | (1.02–1.12) | 0.01 |

| AOR | (95% Confidence Interval) | p-Value | |

| PTV (cc) | 0.98 | (0.93–1.04) | 0.48 |

| V55EQD2 (cc) | 1.05 | (1.01–1.1) | 0.02 |

| AOR | (95% Confidence Interval) | p-Value | |

| PTV (cc) | 0.98 | (0.93–1.04) | 0.49 |

| V50EQD2 (cc) | 1.04 | (1–1.08) | 0.04 |

| ≥Grade 2 Brain Necrosis | |||

| AOR | (95% Confidence Interval) | p-Value | |

| PTV (cc) | 0.99 | (0.93–1.05) | 0.68 |

| V60EQD2 (cc) | 1.09 | (1.03–1.15) | 0.005 |

| AOR | (95% Confidence Interval) | p-Value | |

| PTV(cc). | 0.99 | (0.93–1.05) | 0.63 |

| V55EQD2(cc) | 1.07 | (1.00–1.12) | 0.01 |

| AOR | (95% Confidence Interval) | p-Value | |

| PTV(cc). | 0.99 | (0.93–1.05) | 0.63 |

| V50EQD2(cc) | 1.06 | (1.01–1.11) | 0.01 |

| AOR | (95% Confidence Interval) | p-Value | ||

| PTV (cc) | (<8) | 1.00 | ||

| (≥8, <15) | 0.15 | (0.01–3.18) | 0.22 | |

| (≥15) | 0.26 | (0.02–3.52) | 0.31 | |

| V60EQD2 (cc) | (<10) | 1.00 | ||

| (≥10, <20) | 1.81 | (0.10–32.1) | 0.69 | |

| (≥20) | 18.1 | (1.14–290) | 0.04 | |

| AOR | (95% Confidence Interval) | p-Value | ||

| PTV (cc) | (<8) | 1.00 | ||

| (≥8, <15) | 0.17 | (0.01–3.33) | 0.24 | |

| (≥15) | 0.19 | (0.01–2.94) | 0.23 | |

| V55EQD2 (cc) | (<15) | 1.00 | ||

| (≥15, <30) | 4.45 | (0.33–59.8) | 0.26 | |

| (≥30) | 28.7 | (1.19–691) | 0.04 | |

| AOR | (95% Confidence Interval) | p-Value | ||

| PTV (cc) | (<8) | 1.00 | ||

| (≥8, <15) | 0.26 | (0.02–4.09) | 0.34 | |

| (≥15) | 0.39 | (0.04–3.61) | 0.40 | |

| V50EQD2 (cc) | (<15) | 1.00 | ||

| (≥15, <30) | 1.43 | (0.08–25.3) | 0.81 | |

| (≥30) | 9.28 | (0.69–126) | 0.09 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Murai, T.; Kasai, Y.; Eguchi, Y.; Takano, S.; Kita, N.; Torii, A.; Takaoka, T.; Tomita, N.; Shibamoto, Y.; Hiwatashi, A. Fractionated Stereotactic Intensity-Modulated Radiotherapy for Large Brain Metastases: Comprehensive Analyses of Dose–Volume Predictors of Radiation-Induced Brain Necrosis. Cancers 2024, 16, 3327. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16193327

Murai T, Kasai Y, Eguchi Y, Takano S, Kita N, Torii A, Takaoka T, Tomita N, Shibamoto Y, Hiwatashi A. Fractionated Stereotactic Intensity-Modulated Radiotherapy for Large Brain Metastases: Comprehensive Analyses of Dose–Volume Predictors of Radiation-Induced Brain Necrosis. Cancers. 2024; 16(19):3327. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16193327

Chicago/Turabian StyleMurai, Taro, Yuki Kasai, Yuta Eguchi, Seiya Takano, Nozomi Kita, Akira Torii, Taiki Takaoka, Natsuo Tomita, Yuta Shibamoto, and Akio Hiwatashi. 2024. "Fractionated Stereotactic Intensity-Modulated Radiotherapy for Large Brain Metastases: Comprehensive Analyses of Dose–Volume Predictors of Radiation-Induced Brain Necrosis" Cancers 16, no. 19: 3327. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16193327

APA StyleMurai, T., Kasai, Y., Eguchi, Y., Takano, S., Kita, N., Torii, A., Takaoka, T., Tomita, N., Shibamoto, Y., & Hiwatashi, A. (2024). Fractionated Stereotactic Intensity-Modulated Radiotherapy for Large Brain Metastases: Comprehensive Analyses of Dose–Volume Predictors of Radiation-Induced Brain Necrosis. Cancers, 16(19), 3327. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16193327