Pre-Frailty and Frailty in Hospitalized Older Adults: A Comparison Study in People with and without a History of Cancer in an Acute Medical Unit

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

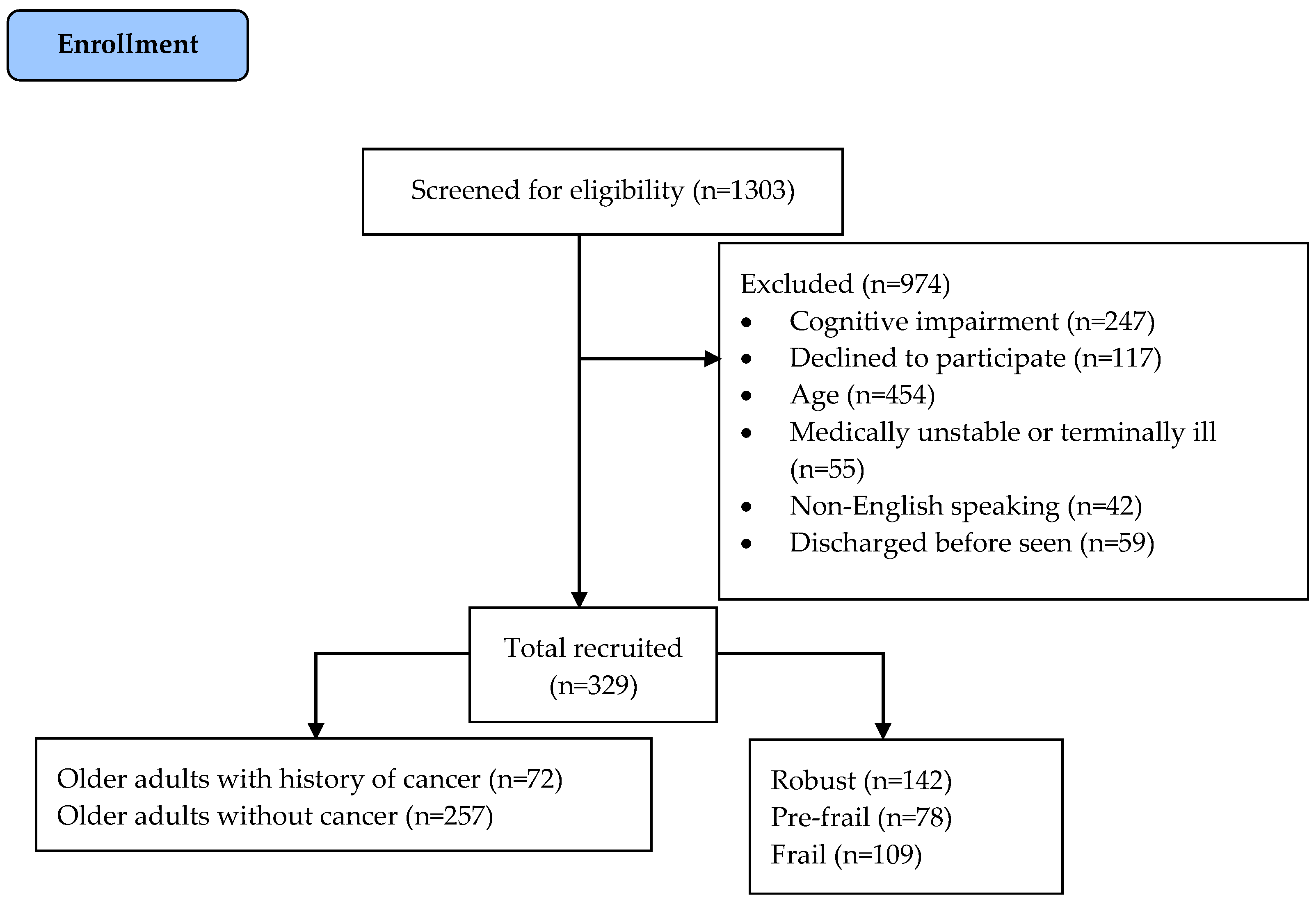

2.2. Recruitment and Ethics

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Frailty Status

2.3.2. History of Cancer

2.3.3. Other Patient Factors and Clinical Outcomes

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Characteristics and Clinical Outcomes Associated with Frailty and Pre-Frailty

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cunha, A.I.L.; Veronese, N.; de Melo Borges, S.; Ricci, N.A. Frailty as a predictor of adverse outcomes in hospitalized older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2019, 56, 100960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boucher, E.L.; Gan, J.M.; Rothwell, P.M.; Shepperd, S.; Pendlebury, S.T. Prevalence and outcomes of frailty in unplanned hospital admissions: A systematic review and meta-analysis of hospital-wide and general (internal) medicine cohorts. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 59, 101947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Fuchs, H.E.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 524–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veronese, N.; Custodero, C.; Cella, A.; Demurtas, J.; Zora, S.; Maggi, S.; Barbagallo, M.; Sabba, C.; Ferrucci, L.; Pilotto, A. Prevalence of multidimensional frailty and pre-frailty in older people in different settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 72, 101498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohile, S.G.; Xian, Y.; Dale, W.; Fisher, S.G.; Rodin, M.; Morrow, G.R.; Neugut, A.; Hall, W. Association of a cancer diagnosis with vulnerability and frailty in older Medicare beneficiaries. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2009, 101, 1206–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ethun, C.G.; Bilen, M.A.; Jani, A.B.; Maithel, S.K.; Ogan, K.; Master, V.A. Frailty and cancer: Implications for oncology surgery, medical oncology, and radiation oncology. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2017, 67, 362–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goede, V. Frailty and cancer: Current perspectives on assessment and monitoring. Clin. Interv. Aging 2023, 18, 505–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apóstolo, J.; Cooke, R.; Bobrowicz-Campos, E.; Santana, S.; Marcucci, M.; Cano, A.; Vollenbroek-Hutten, M.; Germini, F.; Holland, C. Predicting risk and outcomes for frail older adults: An umbrella review of frailty screening tools. JBI Evid. Synth. 2017, 15, 1154–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolfson, D.B.; Majumdar, S.R.; Tsuyuki, R.T.; Tahir, A.; Rockwood, K. Validity and reliability of the edmonton frail scale. Age Ageing 2006, 35, 526–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banna, G.L.; Cantale, O.; Haydock, M.M.; Battisti, N.M.L.; Bambury, K.; Musolino, N.; O’Carroll, E.; Maltese, G.; Garetto, L.; Addeo, A.; et al. International survey on frailty assessment in patients with cancer. Oncologist 2022, 27, e796–e803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huisingh-Scheetz, M.; Walston, J. How should older adults with cancer be evaluated for frailty? J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2017, 8, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher, J.A.; Logan, B.; Reid, N.; Gordon, E.H.; Ladwa, R.; Hubbard, R.E. How frail is frail in oncology studies? A scoping review. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, C.Y.; Sharma, Y.; Yaxley, A.; Baldwin, C.; Miller, M. Use of the patient-generated subjective global assessment to identify pre-frailty and frailty in hospitalized older adults. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2021, 25, 1229–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Extermann, M.; Brain, E.; Canin, B.; Cherian, M.N.; Cheung, K.L.; de Glas, N.; Devi, B.; Hamaker, M.; Kanesvaran, R.; Karnakis, T.; et al. Priorities for the global advancement of care for older adults with cancer: An update of the international society of geriatric oncology priorities initiative. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, e29–e36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handforth, C.; Clegg, A.; Young, C.; Simpkins, S.; Seymour, M.T.; Selby, P.J.; Young, J. The prevalence and outcomes of frailty in older cancer patients: A systematic review. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 1091–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Independent Hospital Pricing Authority. Standardised Mini-Mental State Examination. 2019. Available online: https://www.ihpa.gov.au/what-we-do/standardised-mini-mental-state-examination-smmse (accessed on 25 September 2019).

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (strobe) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Bull. World Health Organ. 2007, 85, 867–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pangman, V.C.; Sloan, J.; Guse, L. An examination of psychometric properties of the mini-mental state examination and the standardized mini-mental state examination: Implications for clinical practice. Appl. Nurs Res. 2000, 13, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottery, F.D.; Isenring, E.; Kasenic, S.; DeBolt, S.P.; Sealy, M.; Jager-Wittenaar, H. Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment; Hanzehogeschool Groningen: Groningen, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Charlson, M.E.; Pompei, P.; Ales, K.L.; MacKenzie, C.R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J. Chronic Dis. 1987, 40, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australia Bureau of Statistics. Sample Size Calculator. 2019. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/D3310114.nsf/home/Sample+Size+Calculator (accessed on 25 September 2019).

- Joosten, E.; Demuynck, M.; Detroyer, E.; Milisen, K. Prevalence of frailty and its ability to predict in hospital delirium, falls, and 6-month mortality in hospitalized older patients. BMC Geriatr. 2014, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andela, R.M.; Dijkstra, A.; Slaets, J.P.; Sanderman, R. Prevalence of frailty on clinical wards: Description and implications. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2010, 16, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammami, S.; Zarrouk, A.; Piron, C.; Almas, I.; Sakly, N.; Latteur, V. Prevalence and factors associated with frailty in hospitalized older patients. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Tan, J.K.; Ismail, A.H.; Ibrahim, R.; Hassan, N.H. Factors associated with frailty in older adults in community and nursing home settings: A systematic review with a meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.; Baek, A.; Kim, Y.; Suh, Y.; Lee, J.; Lee, E.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, E.; Lee, J.; Park, H.S.; et al. Clinical and economic impact of medication reconciliation by designated ward pharmacists in a hospitalist-managed acute medical unit. Res. Social Adm. Pharm. 2022, 18, 2683–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, Y.; Thompson, C.; Shahi, R.; Hakendorf, P.; Miller, M. Malnutrition in acutely unwell hospitalized elderly—“The skeletons are still rattling in the hospital closet”. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2017, 21, 1210–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni Lochlainn, M.; Cox, N.J.; Wilson, T.; Hayhoe, R.P.; Ramsay, S.E.; Granic, A.; Isanejad, M.; Roberts, H.C.; Wilson, D.; Welch, C.; et al. Nutrition and frailty: Opportunities for prevention and treatment. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, C.Y.; Miller, M.; Yaxley, A.; Baldwin, C.; Woodman, R.; Sharma, Y. Effectiveness of combined exercise and nutrition interventions in prefrail or frail older hospitalised patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e040146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, C.Y.; Sharma, Y.; Yaxley, A.; Baldwin, C.; Woodman, R.; Miller, M. Individualized hospital to home, exercise-nutrition self-managed intervention for pre-frail and frail hospitalized older adults: The independence randomized controlled pilot trial. Clin. Interv. Aging 2023, 18, 809–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, R.; Hart, N.H.; Bradford, N.; Agbejule, O.A.; Koczwara, B.; Chan, A.; Wallen, M.P.; Chan, R.J. Diet and exercise advice and referrals for cancer survivors: An integrative review of medical and nursing perspectives. Support Care Cancer 2022, 30, 8429–8439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, R.; Hart, N.H.; Bradford, N.; Wallen, M.P.; Han, C.Y.; Pinkham, E.P.; Hanley, B.; Lock, G.; Wyld, D.; Wishart, L.; et al. Essential elements of optimal dietary and exercise referral practices for cancer survivors: Expert consensus for medical and nursing health professionals. Support Care Cancer 2023, 31, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickson, M.; Child, J.; Collinson, A. Impact of a dietitian in general practice: Care of the frail and malnourished. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2022, 35, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kok, W.; Haverkort, E.; Algra, Y.; Mollema, J.; Hollaar, V.R.Y.; Naumann, E.; de van der Schueren, M.A.E.; Jerković-Ćosić, K. The association between polypharmacy and malnutrition (risk) in older people: A systematic review. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2022, 49, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omlin, A.; Blum, D.; Wierecky, J.; Haile, S.R.; Ottery, F.D.; Strasser, F. Nutrition impact symptoms in advanced cancer patients: Frequency and specific interventions, a case–control study. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2013, 4, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riad, A.; Knight, S.R.; Ghosh, D.; Kingsley, P.A.; Lapitan, M.C.; Parreno-Sacdalan, M.D.; Sundar, S.; Qureshi, A.U.; Valparaiso, A.P.; Pius, R.; et al. Impact of malnutrition on early outcomes after cancer surgery: An international, multicentre, prospective cohort study. Lancet Glob. Health 2023, 11, e341–e349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feliciana Silva, F.; Macedo da Silva Bonfante, G.; Reis, I.A.; André da Rocha, H.; Pereira Lana, A.; Leal Cherchiglia, M. Hospitalizations and length of stay of cancer patients: A cohort study in the brazilian public health system. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazzani, S.; Preisser, F.; Mazzone, E.; Tian, Z.; Mistretta, F.A.; Shariat, S.F.; Saad, F.; Graefen, M.; Tilki, D.; Montanari, E.; et al. In-hospital length of stay after major surgical oncological procedures. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 44, 969–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Numico, G.; Zanelli, C.; Ippoliti, R.; Rossi, M.; Traverso, E.; Antonuzzo, A.; Bellini, R. The hospital care of patients with cancer: A retrospective analysis of the characteristics of their hospital stay in comparison with other medical conditions. Eur. J. Cancer 2020, 139, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitch, M.I.; Nicoll, I.; Lockwood, G.; Strohschein, F.J.; Newton, L. Main challenges in survivorship transitions: Perspectives of older adults with cancer. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2021, 12, 632–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, J.; Butow, P.; Lai-Kwon, J.; Nekhlyudov, L.; Rynderman, M.; Jefford, M. Management of common clinical problems experienced by survivors of cancer. Lancet 2022, 399, 1537–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Presley, C.J.; Krok-Schoen, J.L.; Wall, S.A.; Noonan, A.M.; Jones, D.C.; Folefac, E.; Williams, N.; Overcash, J.; Rosko, A.E. Implementing a multidisciplinary approach for older adults with cancer: Geriatric oncology in practice. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Johnson, M.; Boland, E.; Seymour, J.; Macleod, U. Emergency admissions and subsequent inpatient care through an emergency oncology service at a tertiary cancer centre: Service users’ experiences and views. Support Care Cancer 2019, 27, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montroni, I.; Saur, N.M.; Shahrokni, A.; Suwanabol, P.A.; Chesney, T.R. Surgical considerations for older adults with cancer: A multidimensional, multiphase pathway to improve care. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohile, S.G.; Epstein, R.M.; Hurria, A.; Heckler, C.E.; Canin, B.; Culakova, E.; Duberstein, P.; Gilmore, N.; Xu, H.; Plumb, S. Communication with older patients with cancer using geriatric assessment: A cluster-randomized clinical trial from the national cancer institute community oncology research program. JAMA Oncol. 2020, 6, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuccarino, S.; Monacelli, F.; Antognoli, R.; Nencioni, A.; Monzani, F.; Ferrè, F.; Seghieri, C.; Antonelli Incalzi, R. Exploring cost-effectiveness of the comprehensive geriatric assessment in geriatric oncology: A narrative review. Cancers 2022, 14, 3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariano, C.; Williams, G.; Deal, A.; Alston, S.; Bryant, A.L.; Jolly, T.; Muss, H.B. Geriatric assessment of older adults with cancer during unplanned hospitalizations: An opportunity in disguise. Oncologist 2015, 20, 767–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, S.G.; McCue, P.; Phelps, K.; McCleod, A.; Arora, S.; Nockels, K.; Kennedy, S.; Roberts, H.; Conroy, S. What is comprehensive geriatric assessment (cga)? An umbrella review. Age Ageing 2018, 47, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyers, B.M.; Al-Shamsi, H.O.; Rask, S.; Yelamanchili, R.; Phillips, C.M.; Papaioannou, A.; Pond, G.R.; Jeyabalan, N.; Zbuk, K.M.; Dhesy-Thind, S.K. Utility of the edmonton frail scale in identifying frail elderly patients during treatment of colorectal cancer. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2017, 8, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Røyset, I.M.; Eriksen, G.F.; Benth, J.Š.; Saltvedt, I.; Grønberg, B.H.; Rostoft, S.; Kirkevold, Ø.; Rolfson, D.; Slaaen, M. Edmonton frail scale predicts mortality in older patients with cancer undergoing radiotherapy—A prospective observational study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0283507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| History of Cancer (n = 72) | Without Cancer (n = 257) | p-Value a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age b | 79.7 ± 6.5 | 78.9 ± 8.6 | 0.483 |

| Age (years) c | 0.773 | ||

| 65–79 | 37 (51%) | 137 (53%) | |

| ≥80 | 35 (49%) | 120 (47%) | |

| BMI b | 26.4 ± 5.4 | 27.1 ± 6.5 | 0.396 |

| BMI c | 0.738 | ||

| Under/healthy weight | 31 (43%) | 105 (41%) | |

| Overweight/obese | 41 (57%) | 153 (59%) | |

| Sex c | <0.001 | ||

| Male | 46 (64%) | 105 (41%) | |

| Female | 26 (36%) | 152 (59%) | |

| CCI score b | 4.9 ± 2.0 | 4.3 ± 1.3 | 0.003 |

| CCI score c | 0.556 | ||

| 0–3 | 19 (26%) | 77 (30%) | |

| ≥4 | 53 (74%) | 180 (70%) | |

| No. of medications b | 6.8 ± 3.7 | 6.1 ± 3.6 | 0.155 |

| No. of medications c | 0.790 | ||

| 0–4 | 24 (33%) | 90 (35%) | |

| ≥5 | 48 (67%) | 167 (65%) | |

| On vitamin D c | 0.275 | ||

| Yes | 20 (28%) | 89 (35%) | |

| No | 52 (73%) | 168 (65%) | |

| Living alone c | 0.065 | ||

| Yes | 24 (33%) | 117 (46%) | |

| No | 48 (68%) | 140 (54%) | |

| Education level c | 0.844 | ||

| Tertiary | 31 (43%) | 114 (44%) | |

| Up to secondary | 41 (57%) | 143 (56%) | |

| Income level c | 0.166 | ||

| ≤20 k | 36 (50%) | 105 (41%) | |

| >20 k | 36 (50%) | 152 (59%) | |

| PG-SGA c | 0.001 | ||

| Well nourished | 34 (47%) | 175 (68%) | |

| Malnourished | 38 (53%) | 82 (32%) | |

| EFS category c | 0.772 | ||

| Robust | 30 (42%) | 112 (44%) | |

| Pre-frail/Frail | 42 (58%) | 145 (56%) |

| Characteristics | History of Cancer OR (95% CI) | Without Cancer OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 65–79 | Reference | Reference |

| ≥80 | 0.88 (0.18–4.39) | 1.60 (0.77–3.36) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | Reference | Reference |

| Female | 1.51 (0.35–6.55) | 1.04 (0.55–1.95) |

| BMI | ||

| Underweight/healthy weight | Reference | Reference |

| Overweight/obese | 3.03 (0.76–12.03) | 1.84 (0.98–3.44) |

| CCI score | ||

| 0–3 | Reference | Reference |

| ≥4 | 0.91 (0.14–5.90) | 2.64 (1.13–6.20) * |

| No. of medications | ||

| 0–4 | Reference | Reference |

| ≥5 | 8.26 (1.74–39.16) * | 2.98 (1.57–5.66) * |

| On vitamin D | ||

| Yes | Reference | Reference |

| No | 0.68 (0.14–3.38) | 1.36 (0.72–2.57) |

| Living alone | ||

| No | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 1.76 (0.39–7.96) | 1.09 (0.59–2.01) |

| Education level | ||

| Tertiary | Reference | Reference |

| Up to secondary | 1.78 (0.47–6.73) | 2.14 (1.17–3.91) * |

| Income level | ||

| >20 k | Reference | Reference |

| ≤20 k | 0.29 (0.07–1.17) | 1.18 (0.64–2.18) |

| PG-SGA | ||

| Well nourished | Reference | Reference |

| Malnourished/malnutrition | 8.91 (2.15–36.89) * | 9.03 (4.25–19.20) * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Han, C.Y.; Chan, R.J.; Ng, H.S.; Sharma, Y.; Yaxley, A.; Baldwin, C.; Miller, M. Pre-Frailty and Frailty in Hospitalized Older Adults: A Comparison Study in People with and without a History of Cancer in an Acute Medical Unit. Cancers 2024, 16, 2212. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16122212

Han CY, Chan RJ, Ng HS, Sharma Y, Yaxley A, Baldwin C, Miller M. Pre-Frailty and Frailty in Hospitalized Older Adults: A Comparison Study in People with and without a History of Cancer in an Acute Medical Unit. Cancers. 2024; 16(12):2212. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16122212

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Chad Yixian, Raymond Javan Chan, Huah Shin Ng, Yogesh Sharma, Alison Yaxley, Claire Baldwin, and Michelle Miller. 2024. "Pre-Frailty and Frailty in Hospitalized Older Adults: A Comparison Study in People with and without a History of Cancer in an Acute Medical Unit" Cancers 16, no. 12: 2212. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16122212

APA StyleHan, C. Y., Chan, R. J., Ng, H. S., Sharma, Y., Yaxley, A., Baldwin, C., & Miller, M. (2024). Pre-Frailty and Frailty in Hospitalized Older Adults: A Comparison Study in People with and without a History of Cancer in an Acute Medical Unit. Cancers, 16(12), 2212. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16122212