Advancing Pediatric Oncology Rehabilitation: Survey Findings of Health Professionals’ Perceptions of Barriers to Care and a Framework for Action

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Current State of Knowledge in Pediatric Oncology Rehabilitation

1.2. Objectives

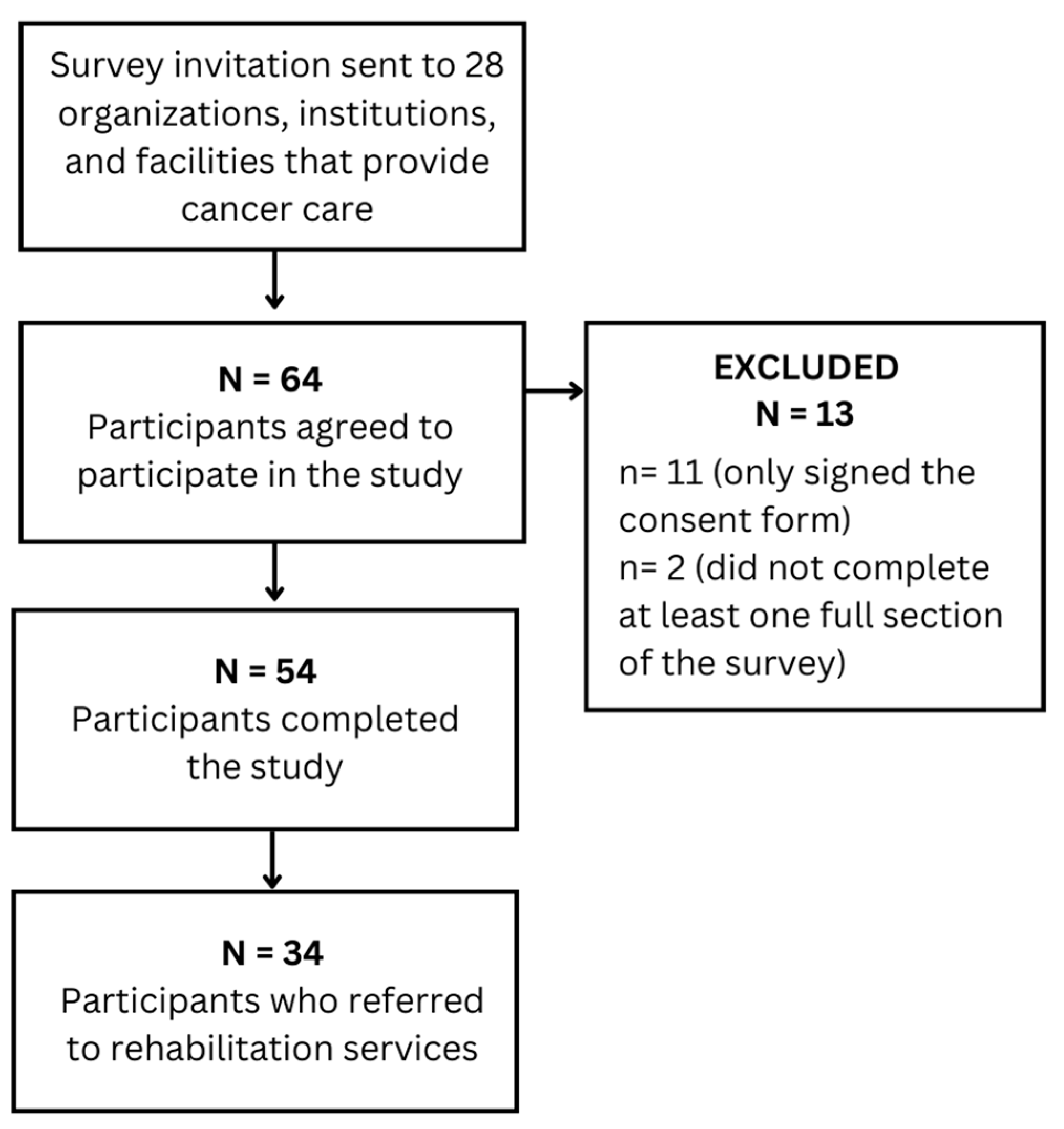

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Instrument and Data Analysis

Variables

- Section I—Demographic information and referral patterns

- ○

- Professional designation: HCPs’ professional designations.

- ○

- Location of practice: Canadian province where HCPs primarily work.

- ○

- Type of service: Primary type of work setting where HCPs work at.

- ○

- Length of experience: Total number of months or years of HCPs’ experience in pediatric oncology.

- ○

- Number of children seen: Total number of children with cancer seen each year by HCPs.

- ○

- Number of children referred to rehabilitation: Total number of children of cancer referred to rehabilitation services each year by HCPs.

- ○

- Frequency of referral to rehabilitation: HCPs’ perceptions of the frequency of referral of children with cancer to rehabilitation services.

- ○

- Percentage of children that received rehabilitation: Percentage of children who ended up receiving rehabilitation, following referral to the service.

- ○

- Reasons children did not receive rehabilitation: Reasons why children did not receive rehabilitation, following referral to the service.

- ○

- Referral location: Type of location where children with cancer were referred to rehabilitation services.

- ○

- Reasons that prompt referral to rehabilitation: Reasons that prompt HCPs’ referral of children with cancer to rehabilitation services.

- Section III—Barriers to rehabilitation and availability of programs and guidelines

- ○

- Availability of rehabilitation programs and clinical practice guidelines: Number of work settings with pediatric oncology rehabilitation programs and clinical practice guidelines in place.

- ○

- Reasons for not having a program: Reasons why the work settings do not have a pediatric oncology rehabilitation program.

- ○

- Barriers to rehabilitation programs: Existing barriers to pediatric oncology rehabilitation programs from the perspective of HCPs.

3. Results

3.1. Medical Team

3.1.1. Demographics

3.1.2. Referrals to Rehabilitation Services (N = 19)

3.1.3. Reasons That Prompt Referral to Rehabilitation Services (N = 19)

3.1.4. Availability of Rehabilitation Programs and Clinical Practice Guidelines (n = 19)

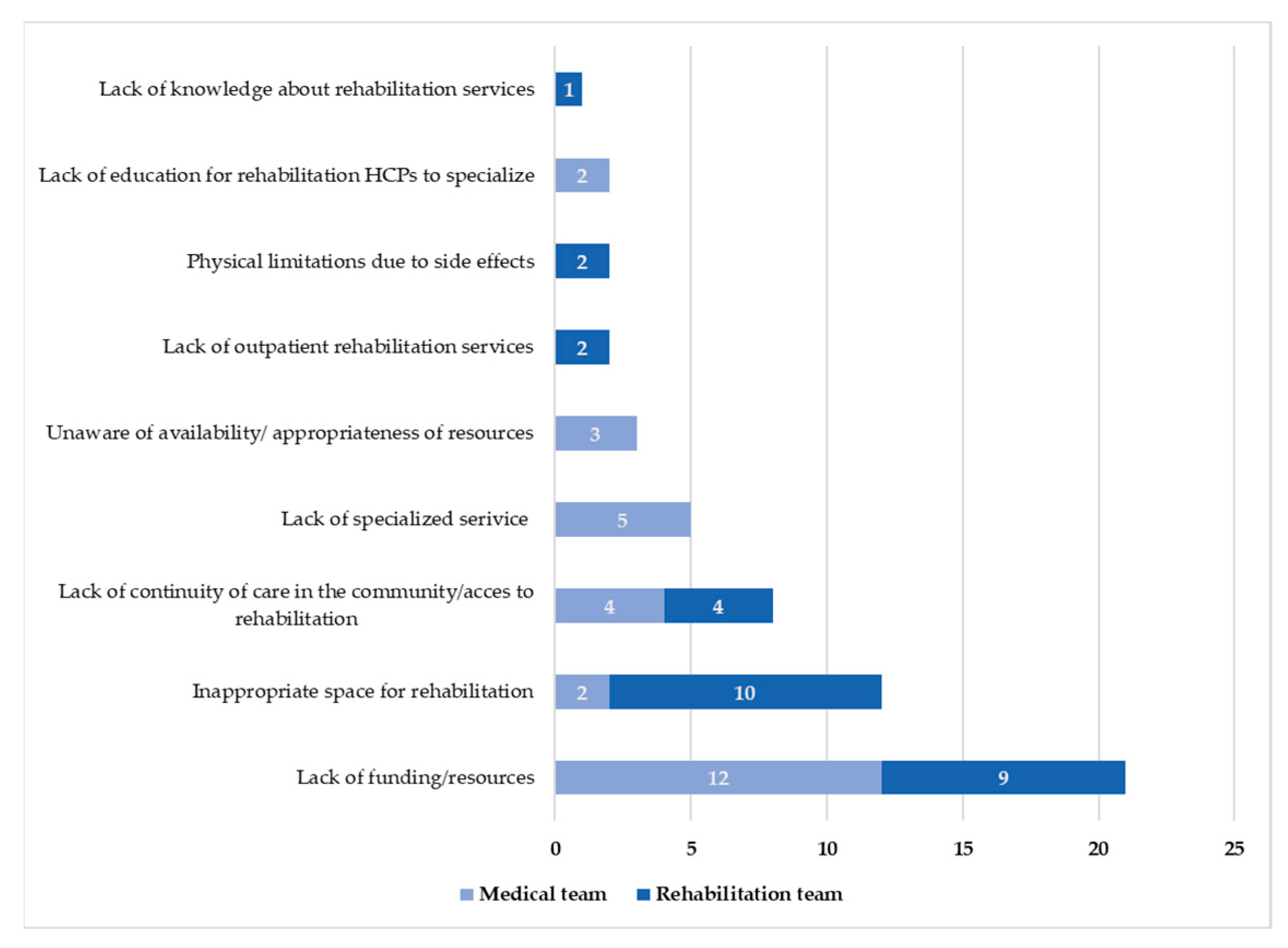

3.1.5. Barriers to Oncology Rehabilitation Programs (N = 19)

3.2. Rehabilitation Team

3.2.1. Demographics

3.2.2. Referrals to Rehabilitation Services (N = 15)

3.2.3. Reasons That Prompt Referral to Rehabilitation Services (N = 15)

3.2.4. Availability of Rehabilitation Programs and Clinical Practice Guidelines (N = 14)

3.2.5. Barriers to Oncology Rehabilitation Programs (N = 14)

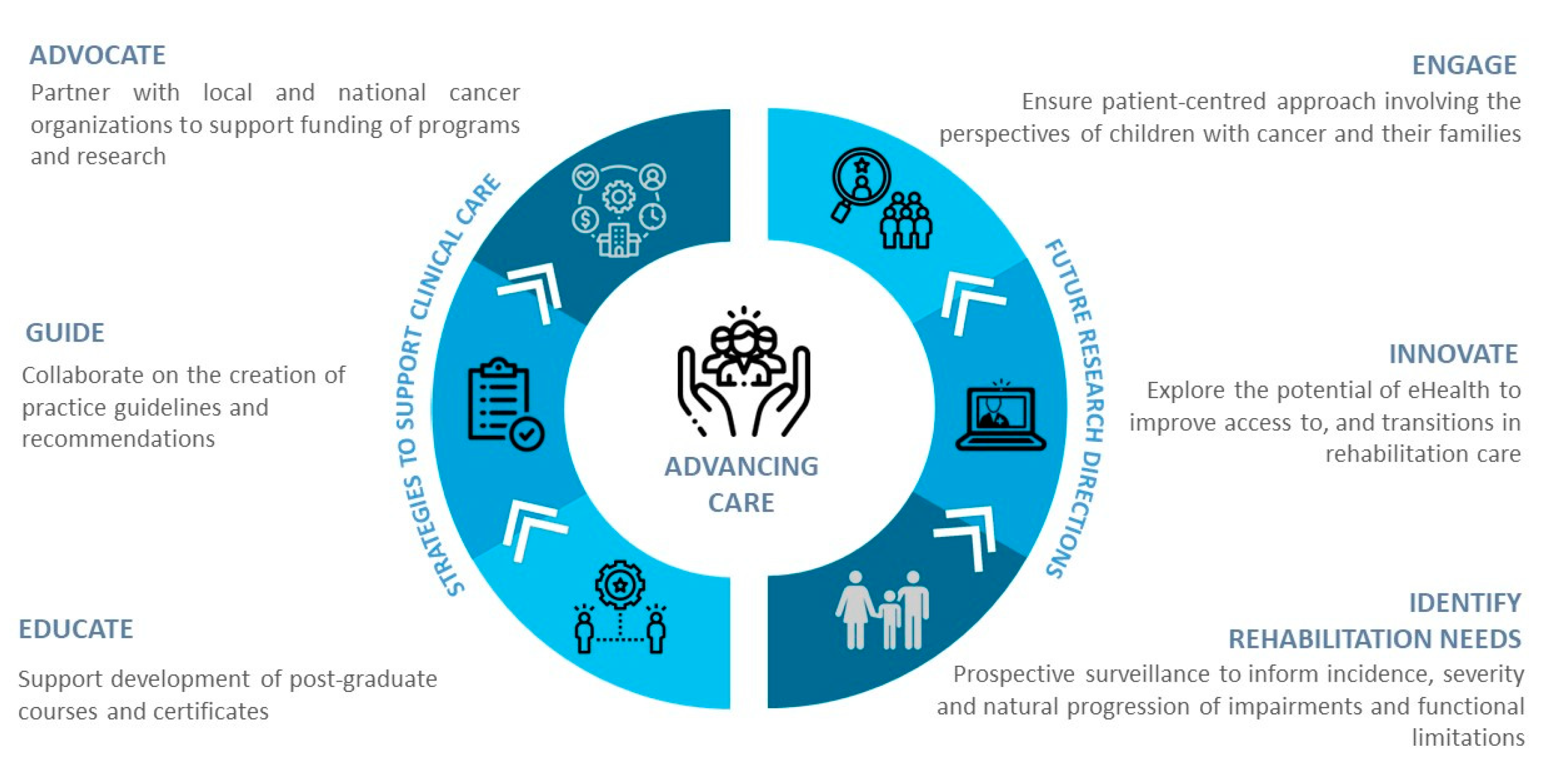

3.3. Thematic Findings to Inform a Framework for Action in Pediatric Oncology Rehabilitation

4. Discussion

4.1. Future Directions

- Advocate: Families of children with cancer play a crucial role in advocating for improvements in cancer treatments, availability of resources, and advancements in research [40]. The creation of strong partnerships between patient advocacy groups as well as local and national non-profit cancer organizations are vital in accessing funds to advance rehabilitation care for children across the cancer trajectory [40].

- Guide: The lack of high-quality rehabilitation-related research evidence is a current barrier to the development of clinical practice guidelines in pediatric oncology. A proposed interim step is for HCPs, researchers, and leaders in the field to collaborate on the creation of expert opinion guidelines and recommendations specific to pediatric oncology rehabilitation services.

- Educate: Existing rehabilitation professional programs lack adequate content in oncology, and pediatric oncology, in particular [39]. To address this current gap, including pediatric oncology in clinical education programs and courses supporting oncology rehabilitation specialization and post-graduate certificates in cancer rehabilitation may serve to accelerate educational efforts in the field [41]. Education and resources are also needed for oncology medical teams to raise awareness of the benefits of rehabilitation.

- Identify: Strategies such as prospective surveillance may help to inform the incidence, severity, and natural progression of impairments and functional limitations of the common childhood cancers [42]. As suggested by Alfano et al. [39], simply implementing a ‘brief patient questionnaire’ provided at oncology visits may allow HCPs to identify patients’ symptoms and make appropriate referrals to rehabilitation services.

- Innovate: To address issues related to access to and transitions in care, research is needed evaluating the potential of eHealth. Telehealth and telecommunication technologies may offer opportunities for virtual delivery of rehabilitation interventions and surveillance for families living in rural and remote locations [41,43] or for those unable to travel to the health centers as a result of barriers such as time and illness [41].

- Engage: To ensure a patient-centred approach, research is needed exploring the perspectives of parents and families towards pediatric oncology rehabilitation programs and family-reported barriers to and facilitators for accessing rehabilitation services.

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Cancer Institute. Cancer in Children and Adolescents. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/types/childhood-cancers/child-adolescent-cancers-fact-sheet#r5 (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Canadian Cancer Society. Canadian Cancer Statistics. Available online: https://cancer.ca/en/research/cancer-statistics (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Deuren, S.; Penson, A.; van Dulmen-den Broeder, E.; Grootenhuis, M.A.; van der Heiden-van der Loo, M.; Bronkhorst, E.; Blijlevens, N.M.A.; Streefkerk, N.; Teepen, J.C.; Tissing, W.J.E.; et al. Prevalence and risk factors of cancer-related fatigue in childhood cancer survivors: A DCCSS Later study. Cancer 2022, 128, 1110–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ness, K.K.; DeLany, J.P.; Kaste, S.C.; Mulrooney, D.A.; Pui, C.; Chemaitilly, W.; Karlage, R.E.; Lanctot, J.Q.; Howell, C.R.; Lu, L.; et al. Energy balance and fitness in adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 2015, 125, 3411–3419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandula, T.; Park, S.B.; Cohn, R.J.; Krishnan, A.V.; Farrar, M.A. Pediatric chemotherapy induced peripheral neuropathy: A systematic review of current knowledge. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2016, 50, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beulertz, J.; Bloch, W.; Prokop, A.; Rustler, V.; Fitzen, C.; Herich, L.; Streckmann, F.; Baumann, F.T. Limitations in Ankle Dorsiflexion Range of Motion, Gait, and Walking Efficiency in Childhood Cancer Survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2016, 39, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, L.S.; Tanner, L.R. Short-Term Recovery of Balance Control: Association with Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy in Pediatric Oncology. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2018, 30, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruitt, D.; Bolikal, P. Rehabilitation of the Pediatric Cancer Patient (Chapter 71). In Cancer Rehabilitation Principles and Practices, 2nd ed.; Stubblefield, M., Ed.; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 896–906. [Google Scholar]

- Ness, K.K.; Hudson, M.M.; Pui, C.H.; Green, D.M.; Krull, K.R.; Huang, T.T.; Robison, L.L.; Morris, E.B. Neuromuscular impairments in adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Associations with physical performance and chemotherapy doses. Cancer 2012, 118, 828–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, C.L.; Gawade, P.L.; Ness, K.K. Impairments that influence physical function among survivors of childhood cancer. Children 2015, 2, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wacker, K.; Tanner, L.; Ovans, J.; Mason, J.; Gilchrist, L. Improving Functional Mobility in Children and Adolescents Undergoing Treatment for Non-Central Nervous System Cancers: A Systematic Review. PM&R 2017, 9, S385–S397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueegg, C.S.; Gianinazzi, M.E.; Michel, G.; von der Weid, N.X.; Bergstraesser, E.; Kuehni, C.E. Do childhood cancer survivors with physical performance limitations reach healthy activity levels? Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2013, 60, 1714–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, A.; Schilperoort, H.; Sargent, B. The effect of exercise and motor interventions on physical activity and motor outcomes during and after medical intervention for children and adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A systematic review. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2020, 152, 103004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchese, V.; Chiarello, L.; Lange, B. Effects of physical therapy intervention for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2004, 42, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanner, L.; Sencer, S.; Hooke, M.C. The Stoplight Program: A Proactive Physical Therapy Intervention for Children With Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2017, 34, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ospina, P.A.; McNeely, M.L. A Scoping Review of Physical Therapy Interventions for Childhood Cancers. Physiother. Can. 2019, 71, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Zheng, J.; Liu, K. Supervised Exercise Interventions in Childhood Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Children 2022, 9, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baxter, M.F.; Newman, R.; Longpré, S.M.; Polo, K.M. Occupational Therapy’s Role in Cancer Survivorship as a Chronic Condition. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2017, 71, 7103090010P1–7103090010P7713001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, H.A.; Arbianingsih; Amal, A.A.; Huriati. The Effectiveness of Play Therapy in Hospitalized Children with Cancer: Systematic Review. J. Nurs. Pract. 2020, 3, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasem, Z.A.; Darlington, A.-S.; Lambrick, D.; Grisbrooke, J.; Randall, D.C. Play in Children With Life-Threatening and Life-Limiting Conditions: A Scoping Review. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2020, 74, 7401205040p1–7401205040p14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heath, S. Cancer rehabilitation for children: A model with potential. Eur. J. Cancer Care 1996, 5, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoerl, R.; Gilchrist, L.; Kanzawa-Lee, G.A.; Donohoe, C.; Bridges, C.; Lavoie Smith, E.M. Proactive Rehabilitation for Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2020, 36, 150983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, F.; Ricci, F.; Botti, S.; Bertin, D.; Breggie, S.; Casalaz, R.; Cervo, M.; Ciullini, P.; Coppo, M.; Cornelli, A.; et al. The Italian consensus conference on the role of rehabilitation for children and adolescents with leukemia, central nervous system, and bone tumors, part 1: Review of the conference and presentation of consensus statements on rehabilitative evaluation of motor aspects. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2020, 67, 12, e28681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, A.; Hassani Mehraban, A. Play-based Occupational Therapy for Hospitalized Children with Cancer: A Short Communication. Iran. Rehabil. J. 2020, 18, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodwin, R.L.; Ma, X.; Ness, K.K.; Kadan-Lottick, N.S.; Wang, R. Physical Therapy Utilization Among Hospitalized Patients with Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2022, 18, e1060–e1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, M.; Huang, S.; Cox, C.L.; Leisenring, W.M.; Oeffinger, K.C.; Hudson, M.M.; Ginsberg, J.; Armstrong, G.T.; Robison, L.L.; Ness, K.K.; et al. Physical therapy and chiropractic use among childhood cancer survivors with chronic disease: Impact on health-related quality of life. J. Cancer Surviv. 2011, 5, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.P.; Syrkin-Nikolau, M.; Farnaes, L.; Shen, D.; Kanegaye, M.; Kuo, D.J. Screening for Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy and Utilization of Physical Therapy in Pediatric Patients Receiving Treatment for Hematologic Malignancies. Blood 2020, 136, 16–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ospina, P.A.; Wiart, L.; Eisenstat, D.D.; McNeely, M.L. Physical Rehabilitation Practices for Children and Adolescents with Cancer in Canada. Physiother. Can. 2019, 72, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canestraro, A.; Nakhle, A.; Stack, M.; Strong, K.; Wright, A.; Beauchamp, M.; Berg, K.; Brooks, D. Oncology Rehabilitation Provision and Practice Patterns across Canada. Physiother. Can. 2013, 65, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohar, S.F.; Marchese, V.; Comito, M. Physician referral frequency for physical therapy in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2010, 27, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, N.K.; Heath, G.; Cameron, E.; Rashid, S.; Redwood, S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suderman, K.; Skene, T.; Sellar, C.; Dolgoy, N.; McNeely, M.L.; Pituskin, E.; Joy, A.A.; Culos-Reed, S.N. Virtual or In-Person: A Mixed Methods Survey to Determine Exercise Programming Preferences during COVID-19. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 6735–6748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennison, J.M.; Ng, A.H.; Bruera, E.; Liu, D.D.; Rianon, N.J. Patient-Reported Continuity of Care and Functional Safety Concerns After Inpatient Cancer Rehabilitation. Oncologist 2021, 26, 887–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfano, C.M.; Cheville, A.L.; Mustian, K. Developing High-Quality Cancer Rehabilitation Programs: A Timely Need. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2016, 35, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grootenhuis, M.A.; Last, B.F. Adjustment and coping by parents of children with cancer: A review of the literature. Support. Care Cancer 1997, 5, 466–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patchell, S.L.; Coulombe, M.M.; Murnane, A.; DeMorton, N.; Bucci, L. Clinician Confidence and Education Preferences for the Treatment of Oncology Patients and Survivors Amongst Physiotherapists and Exercise Professionals: A Comparison of Aya and Adult Oncology Patients. Asia-Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 11, 93. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, G.C.; Miles, G.C.P.; Kotecha, R.S.; Marsh, J.A.; Alessandri, A.J. Regular exercise improves the well-being of parents of children with cancer. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2017, 64, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfano, C.M.; Kent, E.E.; Padgett, L.S.; Grimes, M.; de Moor, J.S. Making Cancer Rehabilitation Services Work for Cancer Patients: Recommendations for Research and Practice to Improve Employment Outcomes. PM&R 2017, 9, S398–S406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argerie, T.; Ramandeep Singh, A.; Poonam, B.; Neil, R.; Marcela, Z. Patient-led research and Advocacy Efforts. Cancer Rep. 2022, 5, 6, e1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stout, N.L.; Brown, J.C.; Schwartz, A.L.; Marshall, T.F.; Campbell, A.M.; Nekhlyudov, L.; Zucker, D.S.; Basen-Engquist, K.M.; Campbell, G.; Meyerhardt, J.; et al. An exercise oncology clinical pathway: Screening and referral for personalized interventions. Cancer 2020, 126, 2750–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, L.R.; Sencer, S.; Gossai, N.; Hooke, M.C.; Watson, D. CREATE Childhood Cancer Rehabilitation Program development: Increase access through interprofessional collaboration. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2022, 69, 11, e29912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheville, A.L.; Moynihan, T.; Loprinzi, C.; Herrin, J.; Kroenke, K. Effect of Collaborative Telerehabilitation on Functional Impairment and Pain among Patients with Advanced-Stage Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Overall n = 34, 100% | ||

|---|---|---|

| Medical Team n = 19, 55.8% | Rehabilitation Team n = 15, 44.1% | |

| Province (n, %) | ||

| Alberta | 7 (36.8%) | 6 (40%) |

| Ontario | 6 (31.5%) | 3 (20%) |

| British Columbia | 4 (21%) | 1 (6.7%) |

| Quebec | - | 4 (26.7%) |

| Nova Scotia | 2 (10.5%) | - |

| Not provided | 1 (6.7%) | |

| Professional designation (n, %) | ||

| Physical therapists | 10 (66.7%) | |

| Nurse and nurse practitioners | 10 (52.6%) | - |

| Oncologists and oncology residents | 9 (47.3%) | - |

| Occupational therapists | 4 (26.7%) | |

| Speech-language pathologists | 1 (6.7%) | |

| Work setting (n, %) | ||

| Acute care hospital | 17 (89.5%) | 10 (66.7%) |

| Cancer hospital | 2 (10.5%) | 3 (20%) |

| Rehabilitation hospital | - | 2 (13.3%) |

| Years of experience (n, %) | ||

| 0.1–5 | 2 (10.5%) | 3 (20%) |

| 5.1–10 | - | 4 (26.7%) |

| 10.1–15 | 4 (21%) | 7 (46.7%) |

| 15.1–20 | 5 (26.3%) | 1 (6.7%) |

| 20.1–30 | 6 (31.5%) | - |

| 30.1–40 | 2 (10.5%) | - |

| Overall n = 34, 100% | ||

|---|---|---|

| Medical Team n = 19, 55.8% | Rehabilitation Team n = 15, 44.1% | |

| Number of C&A seen per year (n, %) | ||

| 1–10 | 4 (26.7%) | |

| 11–20 | 1 (5.3%) | 3 (20%) |

| 21–49 | 6 (31.6%) | 4 (26.7%) |

| 50–100 | 8 (42.2%) | 2 (13.3%) |

| >100 | 4 (21.1%) | 2 (13.3%) |

| How often refer C&A to rehabilitation (n, %) | ||

| Often | 10 (52.6%) | 4 (26.7%) |

| Sometimes | 5 (26.3%) | 8 (53.3%) |

| Rarely | 4 (21.1%) | 2 (13.3%) |

| Never | ||

| Do not know | 1 (6.7%) | |

| Number of C&A referred to rehabilitation (n, %) | ||

| 1–5 | 4 (21.1%) | 4 (26.7%) |

| 6–10 | 4 (21.1%) | 6 (40%) |

| 11–20 | 7 (36.8%) | 4 (26.7%) |

| 21–40 | 4 (21.1%) | 1 (6.7%) |

| Percentage of C&A that received rehabilitation (n, %) | ||

| 75–100% | 14 (73.7%) | 8 (53.3%) |

| 50–75% | 3 (15.8%) | 3 (20%) |

| 25–50% | 1 (6.7%) | |

| <25% | 1 (5.3%) | |

| Don’t know | 1 (5.3%) | 3 (20%) |

| Location/type of service referred (f, %) | ||

| Acute care hospital | 16 (51.6%) | 2 (6.9%) |

| Rehabilitation hospital | 7 (22.6%) | 10 (34.5%) |

| Community/primary care | 6 (19.4%) | 11 (37.9%) |

| Cancer hospital | 2 (6.5%) | |

| Private practice | 4 (13.8%) | |

| Other | 2 (6.9%) | |

| Reasons why C&A referred did not receive rehabilitation (n, %) | ||

| Parent/patient choice | 5 (26.3%) | 5 (33.3%) |

| Don’t know | 4 (21.1%) | 5 (33.3%) |

| Physical therapy was not deemed necessary | 3 (15.8%) | 1 (6.7%) |

| Financial resources | 2 (10.5%) | 2 (13.3%) |

| N/A–100% received | 1 (5.3%) | 1 (6.7%) |

| Other | 4 (21.1%) | 1 (6.7%) |

| Overall n= 34, 100% | ||

|---|---|---|

| Medical Team n = 19, 55.9% | Rehabilitation Team n = 15, 44.1% | |

| Surgery and/or amputation | 13 | 2 |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 12 | 4 |

| Altered mobility | 11 | 2 |

| De-conditioning | 8 | 6 |

| Weakness | 7 | 3 |

| Spinal cord injury | 3 | 2 |

| Bone tumour | 3 | - |

| Brain tumour | 3 | - |

| CNS tumour | 3 | - |

| Abnormal gross and fine motor skills | 1 | 2 |

| Neurological deficits | 1 | 2 |

| Bone marrow transplant | 1 | - |

| Tumour | 1 | - |

| Graft versus host disease of the joints | 1 | - |

| Extended hospital stays | 1 | - |

| Pain | 1 | - |

| Respiratory issues | 1 | - |

| Leukemia | 1 | - |

| Impaired balance | - | 2 |

| Total frequencies (f) | 72 | 25 |

| Overall | ||

|---|---|---|

| n = 33, 100% | ||

| Medical Team | Rehabilitation Team | |

| n = 19, 57.6% | n = 14, 42.4% | |

| Work settings with a rehabilitation program (n, %) | ||

| Yes | 15 (78.9%) | 7 (50%) |

| No | 3 (15.8%) | 6 (42.9%) |

| Do not know | 1 (5.3%) | 1 (7.1%) |

| Reasons for not having a rehabilitation program (f, %) | ||

| Inadequate funding | 2 (33.3%) | 3 (30%) |

| Lack of availability of resources/space | 1 (16.7%) | 4 (40%) |

| Lack of rehabilitation professionals with experience in pediatric oncology | 1 (16.7%) | - |

| Other–few admissions of children with cancer | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (10%) |

| Patients referred to rehabilitation programs that are not oncology specific | 1 (16.7%) | 2 (20%) |

| Lack of evidence to support rehabilitation interventions | - | - |

| Small pediatric oncology population | - | - |

| HCPs who follow pediatric oncology rehabilitation clinical practice guidelines (n, %) | ||

| No | 16 (84.2%) | 7 (50%) |

| Yes | 3 (15.8%) | 5 (35.7%) |

| Do not know | - | 2 (14.3%) |

| Themes | Medical Professional Quotes | Rehabilitation Professional Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Dedicated funding and resources | “Enthusiastic therapists who participate in team-based care. Not sure if we have appropriate facilities.” “(There are) Not enough resources. (Existing) Shared space that limits neutropenic patients from accessing gym if other patients (are) present.” “Off-therapy and after care clinics have no resources for physical rehabilitation.” “We are not funded for outpatient physical rehab(ilitation) services.” “OT (occupational therapy)/PT (physical therapy) have limited time with program (less than 50% of FTE (Full Time Equivalent) for PT (physical therapy) and less than that for OT (occupational therapy)). | “My clinic does not have enough resources and space to provide optimal rehabilitation programs for children and adolescents with cancer.” “Working in the public system funding is always a barrier.” “Not enough space in the clinic for rehabilitation making it difficult to provide service at times.” “Limited equipment and safety devices to challenge ped(iatric)s patients in a safe manner.” “We have no funding for the outpatient clinic, when we do try and cover there, we do not have adequate space at all.” “Human resources vs. needs and number of patients. Some patients under referred.” |

| Improved access and transitions in care | “Many of our children are from outside the region and do not have the services locally or ability to travel to the city for services. Our rehab (rehabilitation) hospital will not see patients while (children with cancer are) still on active treatment i.e., chemotherapy.” “Patients are from a wide geographical area. Access to PT (physical therapy)/OT (occupational therapy) is limited by where (the) patient lives, and resources that may be available in their home communities. Cost of travel (in time and money) can be a barrier for some families accessing rehab(ilitation) services.” “Patients on active therapy are not allowed to have services via our rehabilitation hospital.” “Outpatient access is more limited (same patients that were inpatients). Intensive programming through rehab facility is not usually accessible because of conflicts with ongoing cancer therapy.” | “At times when children still benefit from (an) active intervention, they may receive only consultation or may not be followed long term if they don’t have specific goals at that time. “A limitation is that we don’t always hear how the transfer to (the) community went or do not have a specific physiotherapist to speak with at the time of discharge.” “Referrals to community resources are specific to geographic region and there is a very high level of variation in the services provided.” “For children working on high level skills, the outpatient services tend to be less.” |

| Specialized rehabilitation services | “The physiotherapy team moves it’s PT’s (physical therapists) every few months to different units, so it is difficult for them to specialize.” “We do not have a specific program for this, we have one physiotherapist that has taken this patient group and did a lot of self-learning and advocacy to ensure the unique needs of this population are met. The hospital does not have a system that supports specialization for the physiotherapy group.” “We have (an) inpatient physiotherapist as part of our team. The outpatient setting is more difficult and has no dedicated physiotherapist.” | “Lack of knowledge of doctors / nurses on the contribution (of rehabilitation) especially in occupational therapy.” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ospina, P.A.; Pritchard, L.; Eisenstat, D.D.; McNeely, M.L. Advancing Pediatric Oncology Rehabilitation: Survey Findings of Health Professionals’ Perceptions of Barriers to Care and a Framework for Action. Cancers 2023, 15, 693. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15030693

Ospina PA, Pritchard L, Eisenstat DD, McNeely ML. Advancing Pediatric Oncology Rehabilitation: Survey Findings of Health Professionals’ Perceptions of Barriers to Care and a Framework for Action. Cancers. 2023; 15(3):693. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15030693

Chicago/Turabian StyleOspina, Paula A., Lesley Pritchard, David D. Eisenstat, and Margaret L. McNeely. 2023. "Advancing Pediatric Oncology Rehabilitation: Survey Findings of Health Professionals’ Perceptions of Barriers to Care and a Framework for Action" Cancers 15, no. 3: 693. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15030693

APA StyleOspina, P. A., Pritchard, L., Eisenstat, D. D., & McNeely, M. L. (2023). Advancing Pediatric Oncology Rehabilitation: Survey Findings of Health Professionals’ Perceptions of Barriers to Care and a Framework for Action. Cancers, 15(3), 693. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15030693