Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs) and Patient Experiences in Fertility Preservation: A Systematic Review of the Literature on Adolescents and Young Adults (AYAs) with Cancer

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

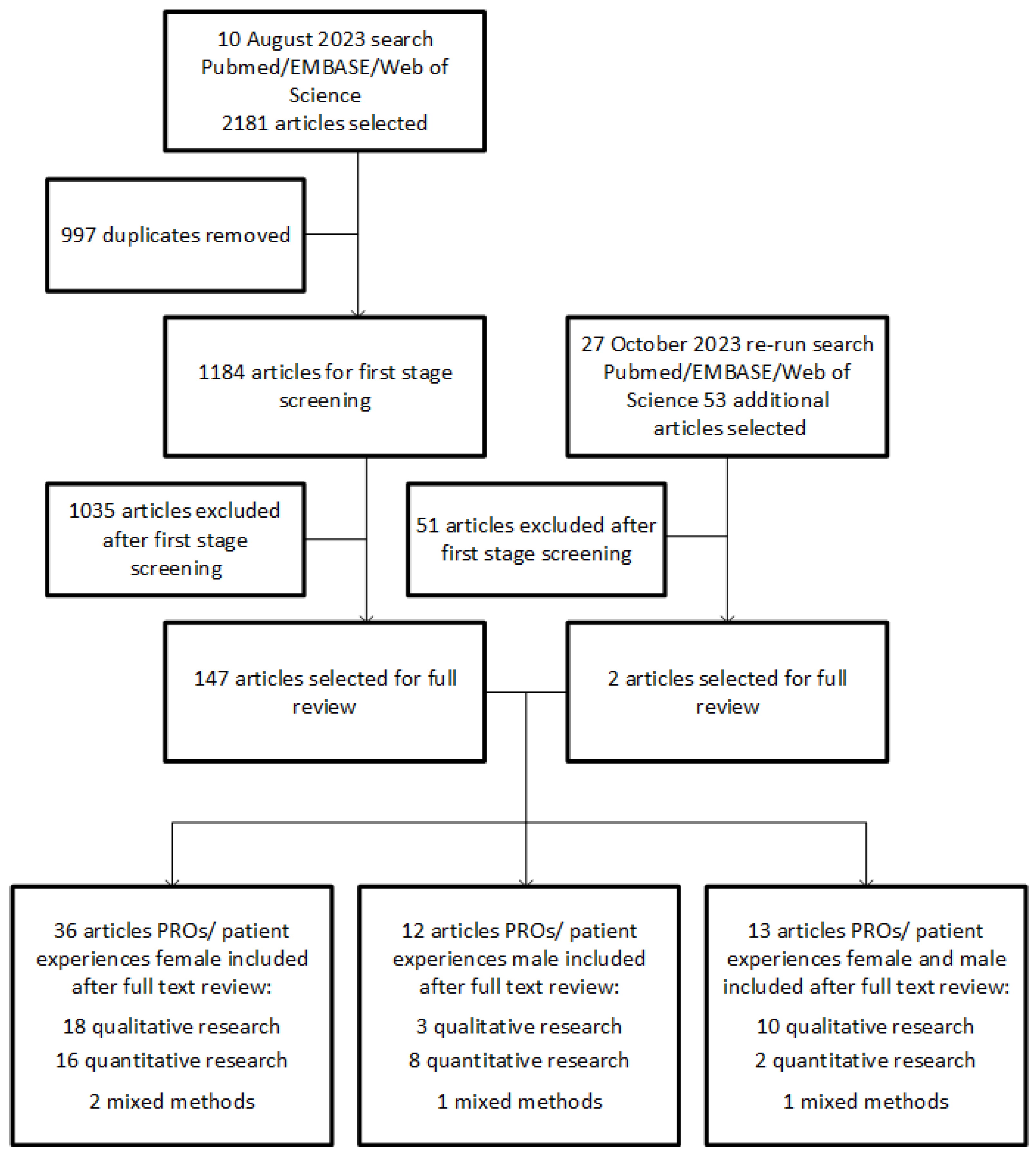

2.1. Search Strategy and Study Selection

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Risk of Bias

3.3. Narrative Synthesis

3.4. Starting a Conversation about Potential Fertility Decline and Referral for Fertility Preservation Counselling

3.4.1. Acknowledging the Importance of Future Fertility

3.4.2. Starting a Conversation about Potential Fertility Decline

3.4.3. (Early) Referral for Fertility Specialist Counselling

3.5. The Need for Verbal and Written (Patient-Specific) Information

3.6. The Psychological Effects of Facing Potential Fertility Decline

3.7. Undergoing Fertility Preservation

3.7.1. Counselling

Communication Skills

Organizational Matters

Costs of Fertility Preservation Treatment

3.7.2. Decision Making about a Fertility Preservation Treatment

3.7.3. Experiences and Needs in Fertility Preservation Treatment

Sense of Control

Hope and Future Oriented

Source of Distress

Short Term Follow Up Consultation after Fertility Preservation

3.8. Worries around Future Fertility and Increase Cancer Risks

3.9. Follow Up after Fertility Preservation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Woodruff, T.K. The emergence of a new interdiscipline: Oncofertility. Cancer Treat. Res. 2007, 138, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Woodruff, T.K. Oncofertility: A grand collaboration between reproductive medicine and oncology. Reproduction 2015, 150, S1–S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letourneau, J.M.; Ebbel, E.E.; Katz, P.P.; Katz, A.; Ai, W.Z.; Chien, A.J.; Melisko, M.E.; Cedars, M.I.; Rosen, M.P. Pretreatment fertility counseling and fertility preservation improve quality of life in reproductive age women with cancer. Cancer 2012, 118, 1710–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fertility preservation and reproduction in patients facing gonadotoxic therapies: An Ethics Committee opinion. Fertil. Steril. 2018, 110, 380–386. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, R.A.; Amant, F.; Braat, D.; D’Angelo, A.; Chuva de Sousa Lopes, S.M.; Demeestere, I.; Dwek, S.; Frith, L.; Lambertini, M.; Maslin, C.; et al. ESHRE guideline: Female fertility preservation. Hum. Reprod. Open 2020, 2020, hoaa052. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zaami, S.; Montanari Vergallo, G.; Moscatelli, M.; Napoletano, S.; Sernia, S.; La Torre, G. Oncofertility: The importance of counseling for fertility preservation in cancer patients. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 25, 6874–6880. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Skaczkowski, G.; White, V.; Thompson, K.; Bibby, H.; Coory, M.; Orme, L.M.; Conyers, R.; Phillips, M.B.; Osborn, M.; Harrup, R.; et al. Factors influencing the provision of fertility counseling and impact on quality of life in adolescents and young adults with cancer. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2018, 36, 484–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentsen, L.; Pappot, H.; Hjerming, M.; Colmorn, L.B.; Macklon, K.T.; Hanghoj, S. How do young women with cancer experience oncofertility counselling during cancer treatment? A qualitative, single centre study at a Danish tertiary hospital. Cancers 2021, 13, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peddie, V.L.; Porter, M.A.; Barbour, R.; Culligan, D.; MacDonald, G.; King, D.; Horn, J.; Bhattacharya, S. Factors affecting decision making about fertility preservation after cancer diagnosis: A qualitative study. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2012, 119, 1049–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Teisberg, E.O. Redefining Health Care: Creating Valie-Based Competition on Results; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A.; et al. The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. Int. Rev. Educ. Train. Libr. Inf. Sci. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, A.S.; Schmidt, K.T.; Kristensen, S.G. Futures and fears in the freezer: Danish women’s experiences with ovarian tissue cryopreservation and transplantation. Reprod. BioMed. Online 2020, 41, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedict, C.; Nieh, J.L.; Hahn, A.L.; McCready, A.; Diefenbach, M.; Ford, J.S. “Looking at future cancer survivors, give them a roadmap”: Addressing fertility and family-building topics in post-treatment cancer survivorship care. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 2203–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentsen, L.; Pappot, H.; Hjerming, M.; Hanghøj, S. Thoughts about fertility among female adolescents and young adults with cancer: A qualitative study. Support. Care Cancer 2023, 31, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro Mitchell, C.N.; Whiting-Collings, L.J.; Christianson, M.S. Understanding Patients’ Knowledge and Feelings Regarding Their Cryopreserved Ovarian Tissue: A Qualitative Interviewing Study. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2020, 9, 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corney, R.; Puthussery, S.; Swinglehurst, J. The stressors and vulnerabilities of young single childless women with breast cancer: A qualitative study. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2014, 18, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahhan, T.; van der Veen, F.; Bos, A.M.E.; Goddijn, M.; Dancet, E.A.F. The experiences of women with breast cancer who undergo fertility preservation. Hum. Reprod. Open 2021, 2021, hoab018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Valle, L.; Corchón, S.; Palop, J.; Rubio, J.M.; Celda, L. The experience of female oncological patients and fertility preservation: A phenomenology study. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2022, 31, e13757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrbar, V.; Urech, C.; Alder, J.; Harringer, K.; Zanetti Dällenbach, R.; Rochlitz, C.; Tschudin, S. Decision-making about fertility preservation-qualitative data on young cancer patients’ attitudes and needs. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2016, 19, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvelink, M.M.; ter Kuile, M.M.; Bakker, R.M.; Geense, W.J.; Jenninga, E.; Louwé, L.A.; Hilders, C.G.; Stiggelbout, A.M. Women’s experiences with information provision and deciding about fertility preservation in the Netherlands: ‘Satisfaction in general, but unmet needs’. Health Expect. 2015, 18, 956–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershberger, P.E.; Sipsma, H.; Finnegan, L.; Hirshfeld-Cytron, J. Reasons Why Young Women Accept or Decline Fertility Preservation After Cancer Diagnosis. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2016, 45, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inhorn, M.C.; Birenbaum-Carmeli, D.; Westphal, L.M.; Doyle, J.; Gleicher, N.; Meirow, D.; Raanani, H.; Dirnfeld, M.; Patrizio, P. Medical egg freezing: The importance of a patient-centered approach to fertility preservation. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2018, 35, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkman, M.; Stern, C.; Neil, S.; Winship, I.; Mann, G.B.; Shanahan, K.; Missen, D.; Shepherd, H.; Fisher, J.R. Fertility management after breast cancer diagnosis: A qualitative investigation of women’s experiences of and recommendations for professional care. Health Care Women Int. 2013, 34, 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komatsu, H.; Yagasaki, K.; Shoda, R.; Chung, Y.; Iwata, T.; Sugiyama, J.; Fujii, T. Repair of the threatened feminine identity: Experience of women with cervical cancer undergoing fertility preservation surgery. Cancer Nurs. 2014, 37, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komatsu, H.; Yagasaki, K.; Yamauchi, H. Fertility decision-making under certainty and uncertainty in cancer patients. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 2018, 15, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niemasik, E.E.; Letourneau, J.; Dohan, D.; Katz, A.; Melisko, M.; Rugo, H.; Rosen, M. Patient perceptions of reproductive health counseling at the time of cancer diagnosis: A qualitative study of female California cancer survivors. J. Cancer Surviv. 2012, 6, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srikanthan, A.; Ethier, J.L.; Amir, E. The Voices of Young Women with Breast Cancer: Providing Support and Information for Improved Fertility Preservation Discussions. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2019, 8, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, S.; Abrol, K.; McDonald, M.; Tonelli, M.; Liu, K.E. Addressing oncofertility needs: Views of female cancer patients in fertility preservation. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2012, 30, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achille, M.A.; Rosberger, Z.; Robitaille, R.; Lebel, S.; Gouin, J.P.; Bultz, B.D.; Chan, P.T. Facilitators and obstacles to sperm banking in young men receiving gonadotoxic chemotherapy for cancer: The perspective of survivors and health care professionals. Hum. Reprod. 2006, 21, 3206–3216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapple, A.; Salinas, M.; Ziebland, S.; McPherson, A.; MacFarlane, A. Fertility issues: The perceptions and experiences of young men recently diagnosed and treated for cancer. J. Adolesc. Health 2007, 40, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, N.; Ali, N. Patient and Physician Perspective on Sperm Banking to Overcome Post-Treatment Infertility in Young Cancer Patients in Pakistan. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2019, 8, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anazodo, A.C.; Gerstl, B.; Stern, C.J.; McLachlan, R.I.; Agresta, F.; Jayasinghe, Y.; Cohn, R.J.; Wakefield, C.E.; Chapman, M.; Ledger, W.; et al. Utilizing the Experience of Consumers in Consultation to Develop the Australasian Oncofertility Consortium Charter. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2016, 5, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armuand, G.M.; Wettergren, L.; Rodriguez-Wallberg, K.A.; Lampic, C. Women more vulnerable than men when facing risk for treatment-induced infertility: A qualitative study of young adults newly diagnosed with cancer. Acta Oncol. 2015, 54, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canzona, M.R.; Victorson, D.E.; Murphy, K.; Clayman, M.L.; Patel, B.; Puccinelli-Ortega, N.; McLean, T.W.; Harry, O.; Little-Greene, D.; Salsman, J.M. A conceptual model of fertility concerns among adolescents and young adults with cancer. Psychooncology 2021, 30, 1383–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canzona, M.R.; Murphy, K.; Victorson, D.; Harry, O.; Clayman, M.L.; McLean, T.W.; Golden, S.L.; Patel, B.; Strom, C.; Little-Greene, D.; et al. Fertility Preservation Decisional Turning Points for Adolescents and Young Adults With Cancer: Exploring Alignment and Divergence by Race and Ethnicity. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2023, 19, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawshaw, M.A.; Glaser, A.W.; Hale, J.P.; Sloper, P. Male and female experiences of having fertility matters raised alongside a cancer diagnosis during the teenage and young adult years. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2009, 18, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, N.J.; Tan, C.Y.; Stelmak, D.; Iannarino, N.T.; Zhang, A.A.; Ellman, E.; Herrel, L.A.; Walling, E.B.; Moravek, M.B.; Chugh, R.; et al. Banking on Fertility Preservation: Financial Concern for Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Patients Considering Oncofertility Services. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2023, 12, 710–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parton, C.; Ussher, J.M.; Perz, J. Hope, burden or risk: A discourse analytic study of the construction and experience of fertility preservation in the context of cancer. Psychol. Health 2019, 34, 456–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salsman, J.M.; Yanez, B.; Snyder, M.A.; Avina, A.R.; Clayman, M.L.; Smith, K.N.; Purnell, K.; Victorson, D. Attitudes and practices about fertility preservation discussions among young adults with cancer treated at a comprehensive cancer center: Patient and oncologist perspectives. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 5945–5955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Logan, S.; Stern, K.; Wakefield, C.E.; Cohn, R.J.; Agresta, F.; Jayasinghe, Y.; Deans, R.; Segelov, E.; McLachlan, R.I.; et al. Supportive oncofertility care, psychological health and reproductive concerns: A qualitative study. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 809–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastings, L.; Baysal, Ö.; Beerendonk, C.C.; IntHout, J.; Traas, M.A.; Verhaak, C.M.; Braat, D.D.; Nelen, W.L. Deciding about fertility preservation after specialist counselling. Hum. Reprod. 2014, 29, 1721–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baysal, Ö.; Bastings, L.; Beerendonk, C.C.; Postma, S.A.; IntHout, J.; Verhaak, C.M.; Braat, D.D.; Nelen, W.L. Decision-making in female fertility preservation is balancing the expected burden of fertility preservation treatment and the wish to conceive. Hum. Reprod. 2015, 30, 1625–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, K.A.; Nadler, T.; Mandel, R.; Burlein-Hall, S.; Librach, C.; Glass, K.; Warner, E. Experience of young women diagnosed with breast cancer who undergo fertility preservation consultation. Clin. Breast Cancer 2012, 12, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, J.K.Y.; Cheung, C.S.Y.; Cheng, H.H.Y.; Yung, S.S.F.; Ng, T.Y.; Tin, W.W.Y.; Yuen, H.Y.; Lam, M.H.C.; Chan, A.S.Y.; Fung, S.W.W.; et al. Knowledge, attitudes and intention on fertility preservation among breast cancer patients. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leflon, M.; Rives-Feraille, A.; Letailleur, M.; Petrovic, C.H.; Martin, B.; Marpeau, L.; Jardin, F.; Aziz, M.; Stamatoulas-Bastard, A.; Dumont, L.; et al. Experience, and gynaecological and reproductive health follow-up of young adult women who have undergone ovarian tissue cryopreservation. Reprod. BioMed. Online 2022, 45, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewinsohn, R.; Zheng, Y.; Rosenberg, S.M.; Ruddy, K.J.; Tamimi, R.M.; Schapira, L.; Peppercorn, J.; Borges, V.F.; Come, S.; Snow, C.; et al. Fertility Preferences and Practices Among Young Women With Breast Cancer: Germline Genetic Carriers Versus Noncarriers. Clin. Breast Cancer 2022, 23, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, C.; Fonseca, A.; Moura-Ramos, M.; Almeida-Santos, T.; Canavarro, M.C. Female cancer patients’ perceptions of the fertility preservation decision-making process: An exploratory prospective study. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2018, 36, 364–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mersereau, J.E.; Goodman, L.R.; Deal, A.M.; Gorman, J.R.; Whitcomb, B.W.; Su, H.I. To preserve or not to preserve: How difficult is the decision about fertility preservation? Cancer 2013, 119, 4044–4050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruddy, K.J.; Gelber, S.I.; Tamimi, R.M.; Ginsburg, E.S.; Schapira, L.; Come, S.E.; Borges, V.F.; Meyer, M.E.; Partridge, A.H. Prospective study of fertility concerns and preservation strategies in young women with breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 1151–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri, M.; Pagan, E.; Bagnardi, V.; Bianco, N.; Gallerani, E.; Buser, K.; Giordano, M.; Gianni, L.; Rabaglio, M.; Freschi, A.; et al. Fertility concerns, preservation strategies and quality of life in young women with breast cancer: Baseline results from an ongoing prospective cohort study in selected European Centers. Breast 2019, 47, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauerbrun-Cutler, M.T.; Pandya, S.; Recabo, O.; Raker, C.; Clark, M.A.; Robison, K. Survey of young women with breast cancer to identify rates of fertility preservation (FP) discussion and barriers to FP care. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2023, 40, 2003–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urech, C.; Ehrbar, V.; Boivin, J.; Müller, M.; Alder, J.; Zanetti Dällenbach, R.; Rochlitz, C.; Tschudin, S. Knowledge about and attitude towards fertility preservation in young female cancer patients: A cross-sectional online survey. Hum. Fertil. 2018, 21, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Berg, M.; Kaal, S.E.J.; Schuurman, T.N.; Braat, D.D.M.; Mandigers, C.; Tol, J.; Tromp, J.M.; van der Vorst, M.; Beerendonk, C.C.M.; Hermens, R. Quality of integrated female oncofertility care is suboptimal: A patient-reported measurement. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 2691–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walasik, I.; Falis, M.; Płaza, O.; Szymecka-Samaha, N.; Szymusik, I. Polish Female Cancer Survivors’ Experiences Related to Fertility Preservation Procedures. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2023, 12, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Wolff, M.; Giesecke, D.; Germeyer, A.; Lawrenz, B.; Henes, M.; Nawroth, F.; Friebel, S.; Rohde, A.; Giesecke, P.; Denschlag, D. Characteristics and attitudes of women in relation to chosen fertility preservation techniques: A prospective, multicenter questionnaire-based study with 144 participants. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2016, 201, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanagnolo, V.; Sartori, E.; Trussardi, E.; Pasinetti, B.; Maggino, T. Preservation of ovarian function, reproductive ability and emotional attitudes in patients with malignant ovarian tumors. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2005, 123, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edge, B.; Holmes, D.; Makin, G. Sperm banking in adolescent cancer patients. Arch. Dis. Child. 2006, 91, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krouwel, E.M.; Jansen, T.G.; Nicolai, M.P.J.; Dieben, S.W.M.; Luelmo, S.A.C.; Putter, H.; Pelger, R.C.M.; Elzevier, H.W. Identifying the Need to Discuss Infertility Concerns Affecting Testicular Cancer Patients: An Evaluation (INDICATE Study). Cancers 2021, 13, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacey, A.; Merrick, H.; Arden-Close, E.; Morris, K.; Rowe, R.; Stark, D.; Eiser, C. Implications of sperm banking for health-related quality of life up to 1 year after cancer diagnosis. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 108, 1004–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, S.; Lambert, S.D.; Lee, V.; Loiselle, C.G.; Chan, P.; Gupta, A.; Lo, K.; Rosberger, Z.; Zelkowitz, P. A fertility needs assessment survey of male cancer patients. Psychooncology 2018, 27, 2747–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schover, L.R.; Brey, K.; Lichtin, A.; Lipshultz, L.I.; Jeha, S. Knowledge and experience regarding cancer, infertility, and sperm banking in younger male survivors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002, 20, 1880–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, W.; Gan, D.; Cuihua, S.; Peitao, W. A questionnaire survey on awareness of reproductive protection and autologous sperm preservation among cancer patients. J. Men’s Health 2020, 16, e19–e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, S.; Fuller-Thomson, E.; Dwyer, C.; Greenblatt, E.; Shapiro, H. “Just what the doctor ordered”: Factors associated with oncology patients’ decision to bank sperm. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2012, 6, E174–E178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, G.; Cao, M.; Yin, L.; Xing, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J. Level of Knowledge and Needs on Fertility Preservation in Reproductive-Aged Male Patients with Cancer. J. Cancer Educ. 2020, 35, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayiira, A.; Neda John, J.; Zaake, D.; Xiong, S.; Kambugu Balagadde, J.; Gomez-Lobo, V.; Wabinga, H.; Ghebre, R. Understanding Fertility Attitudes and Outcomes Among Survivors of Adolescent and Young Adult Cancers in a Low-Resource Setting: A Registry-Based Computer-Assisted Telephone Interview Survey. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2023, 12, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marino, J.L.; Peate, M.; McNeil, R.; Orme, L.M.; McCarthy, M.C.; Glackin, A.; Sawyer, S.M. Experiences of Family and Partner Support in Fertility Decision-Making among Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer: A National Australian Study. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2023; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlossman, J.; Vu, M.; Samborski, A.; Breit, K.; Thevenet-Morrison, K.; Wilbur, M. Identifying barriers individuals face in accessing fertility care after a gynecologic cancer diagnosis. Gynecol. Oncol. Rep. 2023, 49, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Vogt, K.S.; Hughes, J.; Wilkinson, A.; Mahmoodi, N.; Skull, J.; Wood, H.; McDougall, S.; Slade, P.; Greenfield, D.M.; Pacey, A.; et al. Preserving fertility in women with cancer (PreFer): Decision-making and patient-reported outcomes in women offered egg and embryo freezing prior to cancer treatment. Psychooncology 2018, 27, 2725–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrbar, V.; Scherzinger, L.; Urech, C.; Rochlitz, C.; Tschudin, S.; Sartorius, G. Fertility preservation in male cancer patients: A mixed methods assessment of experiences and needs. Urol. Oncol. 2022, 40, 385.e319–385.e325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ussher, J.M.; Parton, C.; Perz, J. Need for information, honesty and respect: Patient perspectives on health care professionals communication about cancer and fertility. Reprod. Health 2018, 15, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawshaw, M.; Glaser, A.; Hale, J.; Sloper, P. Professionals’ view on the issues and challenges arising from providing a fertility preservations service sperm banking to teenage males with cancer. Hum. Fertil. 2004, 7, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, J.F.; Ott, M.A. Fertility Preservation after a Cancer Diagnosis: A Systematic Review of Adolescents’, Parents’, and Providers’ Perspectives, Experiences, and Preferences. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2016, 29, 585–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daly, C.; Micic, S.; Facey, M.; Speller, B.; Yee, S.; Kennedy, E.D.; Corter, A.L.; Baxter, N.N. A review of factors affecting patient fertility preservation discussions & decision-making from the perspectives of patients and providers. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2019, 28, e12945. [Google Scholar]

- Linnane, S.; Quinn, A.; Riordan, A.; Dowling, M. Women’s fertility decision-making with a diagnosis of breast cancer: A qualitative evidence synthesis. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2022, 28, e13036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clasen, N.H.Z.; van der Perk, M.E.M.; Neggers, S.; Bos, A.M.E.; van den Heuvel-Eibrink, M.M. Experiences of Female Childhood Cancer Patients and Survivors Regarding Information and Counselling on Gonadotoxicity Risk and Fertility Preservation at Diagnosis: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2023, 15, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, V.; Ferreira, P.L.; Saleh, M.; Tamargo, C.; Quinn, G.P. Perspectives of Young Women With Gynecologic Cancers on Fertility and Fertility Preservation: A Systematic Review. Oncologist 2022, 27, E251–E264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macklon, K.T.; Cjm Fauser, B. The female post-cancer fertility-counselling clinic: Looking beyond the freezer. A much needed addition to oncofertility care. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2019, 39, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salonia, A.; Capogrosso, P.; Castiglione, F.; Russo, A.; Gallina, A.; Ferrari, M.; Clementi, M.C.; Castagna, G.; Briganti, A.; Cantiello, F.; et al. Sperm banking is of key importance in patients with prostate cancer. Fertil. Steril. 2013, 100, 367–372.e361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Origin | Year | Aim | Type | Study Design | Study Period | Eligibility/Inclusion Criteria | Year of FP Counselling | Sample | Data Collection | Relevant Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | |||||||||||

| Bach et al. [13] | Denmark | 2020 | Explore patients’ experiences with ovarian tissue cryopreservation (OTC), including their reflections on the long-term storage of tissue and the use of surplus tissue. | Qualitative | Retrospective | 2017–2019 | Underwent OTC in Denmark between 2003 and 2018. | 2003–2018 | N = 42 (age range at time of interview: 22 years—early 50 s), 32 of whom had ovarian tissue transplanted (age of OTC: 15–42 years); Unclear follow up time. Multiple diagnoses, i.a. breast cancer and lymphoma | Semi-structured interviews | OTC can be regarded as a ‘hope technology’, but in contrast to the freezing of oocytes and embryos, ovarian tissue is interlinked with scenarios of risk and disease connected to tissue transplantation. It is perceived as a future means to provide options beyond the scope of reproduction. There is a need for the specialized and sensitive provision of information, regular follow-up, and fertility counselling after OTC and cancer treatment |

| Bastings et al. [42] | The Netherlands | 2014 | How do female patients experience FP consultations with a specialist in reproductive medicine, and how does this influence subsequent FP decision-making? | Quantitative | Retrospective | 2013 | Aged ≥ 16 years when the study was conducted. Had undergone FP after FP counselling. | 2008–2013 | Response rate: N = 60/108 patients (56%) who returned completed questionnaires; Mean age: 29 years; Mean follow up: 2 years; Multiple diagnoses, i.a. breast cancer (60%) and lymphoma (18%) | Study specific questionnaire and Decisional Conflict Scale (DCS) and Decisional Regret Scale | The majority of patients were satisfied with FP counselling. Some patients wished for more information about specific subjects (e.g., the influence of hormones and ovarian enlargement on the risk that chemotherapy would cause ovarian failure). Negative experiences were found to be associated with decisional conflict and decision regret. |

| Baysal et al. [43] | The Netherlands | 2015 | To identify the issues that women consider to be important in their decision-making process, at the time of FP counselling, about whether or not to undergo FP in a setting where financial factors do not play a role. Furthermore, to investigate how these issues are related to patients’ FP choices. | Quantitative | Retrospective | 2013 | Age ≥ 16 years, not severely diseased, no psychological problems. Received FP counselling and if at least one FP option was offered after FP counselling. | 1999–2013 | Response rate: N = 87/143 patients (61%) who returned completed questionnaires (49 who chose to undergo FP, 38 of whom refrained from FP options). Mean age at counselling: 28 years; Mean follow-up time for the total group of responders: 3 years (SD 2); Multiple diagnoses, i.a. breast cancer (58%) and lymphoma (18%) | Study specific questionnaire | FP decision-making in young women scheduled for gonadotoxic therapy is mainly based on weighing two issues: the intensity of the wish to conceive a child in the future and the expected burden of undergoing fertility preservation treatment. |

| Benedict et al. [14] | USA | 2021 | To explore survivors’ recommendations in terms of addressing fertility and family-building needs after cancer. | Qualitative | Retrospective | Unclear | Female cancer survivors aged 15–39 years, completion of gonadotoxic treatment, had not had a child since cancer diagnosis and reported parenthood desires or undecided family-building plans. | Unclear | N = 25; Mean age: 29 years; mean age at diagnosis: 23 years. Multiple diagnoses, i.a. Hodgkin lymphoma (24%), breast cancer (20%), and leukemia (12%) | Semi-structured interviews | Six primary recommendations were identified for post-treatment care. Health care providers should offer more information about fertility and family building. Providers should not make assumptions about patient’s family-building desires and intentions. Emotional support should be offered. There is an overarching need for guidance about how to translate information into actionable next steps. Improve communication. Provide financial information and refer to peer support resources. |

| Bentsen et al. [8] | Denmark | 2021 | To examine how female AYA cancer patients and survivors experienced initial and specialized oncofertility counselling and to present their specific suggestions on how to improve oncofertility counselling. | Qualitative | Retrospective | 2020 | Female cancer patients and survivors aged 18–39 years. | Unclear | N = 12 patients, 20–35 years; Mean age: 28 years; Patients in treatment (N = 4) and post treatment (N = 8); Unclear follow up time. Multiple diagnoses, i.a. ovarian cancer (25%) and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (25%) | Semi-structured interviews | There is a continuing problem regarding insufficient oncofertility counselling to AYAs with cancer. There is a need for further improvement to ensure uniform and adequate information, especially in initial oncofertility counselling. Patients suggest focus on verbal and written information, along with communication upskilling to improve oncofertility counselling |

| Bentsen et al. [15] | Denmark | 2023 | To explore thoughts about fertility among female AYAs with cancer. | Qualitative | Retrospective | 2020–2021 | Female AYAs and cancer survivors (18–39 years). | Unclear | N = 12; Mean age; 28 years; Multiple diagnoses, i.a. Hodgkin’s lymphoma (25%) and breast cancer (17%) | Semi-structured interviews | Four main themes were found: Female AYAs held on to the hope of having children in the future, female AYAs experienced time pressure and waiting times as a sprint as well as a marathon, female AYAs faced existential and ethical choices about survival and family formation, and female AYAs felt a loss of control of their bodies |

| Cordeiro Mitchell et al. [16] | USA | 2020 | To determine the extent to which patients understand the potential fertility and medical benefits of the cryopreservation of ovarian tissue, the desire for future fertility, and feelings that patients have about the cryopreservation procedure. | Qualitative | Retrospective | Unclear | Age ≥ 18 years, had undergone ovarian tissue cryopreservation. | 2006–2017 | N = 8/9; Age at interview: 19–37 years; Mean follow up time: 5 years. Multiple diagnoses: hematologic or gynecological cancer | Telephone semi-structured interviews | There is a knowledge gap among patients with cryopreserved ovarian tissue regarding the uses and benefits of OTC. There is also a strong desire among these patients for improved education about this technology. |

| Corney et al. [17] | UK | 2014 | To focus on the stressors and vulnerabilities faced by young, single, childless women who were diagnosed with a first episode of breast cancer. | Qualitative | Retrospective | Unclear | Single, childless women with a first episode of breast cancer. | Unclear | N = 10; Age ranges: 27–41 years at diagnoses, 30–44 years at interview; Time range since diagnosis: 8 months–5 years; Single diagnosis of breast cancer | Semi-structured interviews | Young, childless single women with breast cancer face additional vulnerabilities and may benefit from tailored support from health care providers and interventions specifically targeted at them. |

| Dahhan et al. [18] | The Netherlands | 2021 | To explore how women experience oocyte or embryo banking when they have just been diagnosed with breast cancer. | Qualitative | Retrospective | 2013–2014 | Women aged 18–43 years, newly diagnosed with breast cancer and who banked their oocytes of embryos in two Dutch university medical centers. | 2013–2014 | N = 21/28; Mean age: 32 years; On average, 8 months after fertility preservation; Single diagnosis of breast cancer | Semi-structured interviews | Three main experiences: the burden of FP, the new identity of a fertility patient, and coping with breast cancer through FP. |

| Del Valle et al. [19] | Spain | 2022 | To identify cancer patients’ specific needs and experiences regarding FP. | Qualitative | Retrospective | 2019 | Females of reproductive age (18–44 years) diagnosed with cancer that could affect reproductive function due to the need to receive gonadotoxic treatments, who had undergone treatment for FP. | 2017–2019 | Response rate: N = 14/24 (58%); Mean age = 32 years (SD: 5); Time since FP was between 8 and 20 months; Multiple diagnoses, i.a. breast cancer (57%) and lymphoma (14%) | Semi-structured interviews | In the ovarian tissue freezing group, feelings, emotions, stress, and the impact of the diagnosis were more intense due the fact that this procedure has to be carried out quickly, making it more traumatic. Patients suffered from difficulties when making decision about fertility whilst dealing with a cancer diagnosis. They needed adequate information and support from health care providers. Despite increasing awareness of FP, there is a lack of knowledge regarding patient experiences and needs related to this process. |

| Ehrbar et al. [20] | Switzerland | 2016 | To assess the significance of fertility issues in cancer patients, their attitude toward fertility preservation, potential decisional conflicts, and patients’ needs during the decision-making process. | Qualitative | Retrospective | 2012 | Female cancer survivors aged between 18 and 45 years, had a cancer diagnosis within the last 10 years with a treatment that might have affected their fertility. | 1999–2011 | Response rate: N = 12/21 (57%); Age range: 21–45 years at time of study; Mean time since diagnosis: 5 years; Multiple diagnoses, i.a. breast cancer (67%) | 4 focus groups | The significance of fertility was high and attitudes toward FP were positive. Religious and ethical reservations were not negligible. More support was desired and specific tools would be beneficial. |

| Garvelink et al. [21] | The Netherlands | 2013 | To describe the experiences of women who had received at least one counselling consultation on FP in relation to information provision and decision making about FP. | Qualitative | Retrospective | 2007–2008 | Women who had at least one counselling consultation about FP, between 18 and 40 years of age at the time of counselling. | 2002–2007 | Response rate: N = 34/53 (64%); Mean age: 33 years at time of interview, 31 years at FP consultation; Mean time since counselling: 24 months; Multiple diagnoses, i.a. breast cancer (82%), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (6%), and Hodgkin lymphoma (6%) | Semi-structured interviews | Women recommended standardization of information provision, improvement of communication, and availability of FP-specific patient information materials to improve future information provision processes. Overall, women were satisfied with the timing and content of information provision, but women were less positive about the need to be assertive to obtain information and the multiplicity of decisions and actions to be carried out in a very short time frame. |

| Hershberger et al. [22] | USA | 2016 | To help understand young women’s reasons for accepting or declining FP following a cancer diagnoses. | Qualitative | Retrospective | Unclear | Female cancer patients aged between 18–42 years, eligible for FP. Made a decision regarding FP within the past 18 months. | Unclear | N = 27, of which 14 declined FP, 13 accepted FP; Mean age: 29 years; Average: 5 months prior to study diagnosed with cancer; Multiple diagnoses, i.a. breast cancer (52%), Hodgkin’s lymphoma (19%), and ovarian cancer (15%) | Study specific questionnaire interviews by telephone (N = 21) or email (N = 6) | The primary factor upon which many patients-based decisions related to FP was whether the immediate emphasis of care should be placed on surviving cancer of securing options for future biological motherhood. |

| Hill et al. [44] | Canada | 2012 | To gather information from young patients with breast cancer about their experiences with FP referrals, consultations, and decision making. | Quantitative | Retrospective | Unclear | Patients with breast cancer who attended an FP consultation. | 2005–2011 | Response rate: N = 27/53 (51%); Mean age at diagnosis: 31 years; No clear follow up time; Single diagnosis of breast cancer | Multiple choice and open-ended survey | FP referral should be initiated by the surgeon as soon as a diagnosis of invasive cancer is made; women need written materials before and after FP consultation; and a FP counsellor who is able to spend additional time after the consultation could help with decision making. |

| Inhorn et al. [23] | USA/Israel | 2018 | To examine women’s motivations and experiences, including their perceived need for patient-centered care following the diagnosis of a life-threatening illness. | Qualitative | Retrospective | 2014–2016 | Women who had completed at least one medical egg freezing cycle at one of the six participating IVF clinics (4 USA/2 Israel). | 2000–2016 | N = 45 (33 USA/12 Israel), including 35 patients with oncologic indication; Follow up time not clear; Multiple diagnoses, i.a. breast cancer (43%) | Semi-structured Interviews | Special needs of medical egg freezing patients who tend to be young (<30 years), unmarried, and resource-constrained, making them highly vulnerable. Facing the frightening double jeopardy of cancer and fertility loss. |

| Kirkman et al. [24] | Australia | 2013 | To learn from women about their experiences of cancer care in relation to their fertility, to consider their recommendations to clinicians, and ultimately, to inform and enhance the provision of supportive care to such women. | Qualitative | Retrospective | Unclear | Women diagnosed with breast cancer, 18–45 years of age, and at least 1-year postdiagnosis | Unclear | N = 10; Age range: 26–45 years at interview (age range at diagnosis was 25–41 years); Follow up time not completely clear (based on age difference: 1–7 years); Single diagnosis of breast cancer | Semi-structured interviews by phone (N = 9) or in person (N = 1) | Fertility was important to participants. Complex psychological needs arising from the ramifications of living with cancer. Clinicians should be aware of the significance of fertility and avoid making assumptions based on the women’s age, marital status, or other characteristics. Women valued referral to a fertility specialist at the earliest opportunity and valued multidisciplinary treatment. |

| Ko et al. [45] | China | 2023 | To assess the knowledge, perceptions, and intentions regarding FP among women diagnosed with breast cancer. | Quantitative | Retrospective | 2020–2022 | Women diagnosed with breast cancer, 18–45 years or age. | Unclear | Response rate N = 410/461 (89%); Mean age at questionnaire: 40 years; Follow up time: less than five years for 72% of subjects. Single diagnosis of breast cancer | Study specific questionnaire | Younger age and higher educational level were significantly associated with increased awareness of FP. Awareness and acceptance of different FP methods was generally low. |

| Komatsu et al. [25] | Japan | 2014 | To explore the experience of undergoing a radical trachelectomy from the perspective of women with cervical cancer. | Qualitative | Retrospective | 2011–2012 | Women diagnosed with cervical cancer who had undergone radical trachelectomy (between 2006–2010) and who were encouraged to attempt conception after 6 months without cancer recurrence. | 2006–2010 | N = 15; Mean age at time of surgery: 32 years; No clear follow up time; Single diagnosis of cervical cancer | Semi-structured interviews | Women who undergo radical trachelectomy experience an identity transformation process. FP repairs the threatened feminine identity and keeps a window of hope open. |

| Komatsu et al. [26] | Japan | 2018 | To understand how women with breast cancer receiving FP counselling make fertility-related decisions. | Qualitative | Retrospective | 2016 | Women who were diagnosed with breast cancer and received FP counselling. Patients with strong physical discomfort or depression were excluded | 2010–2014 | N = 11; Mean age: 41 years at interview (SD 4 years). No clear follow up time; Single diagnosis of breast cancer | Semi-structured interviews | After receiving FP counselling, women with breast cancer made difficult decisions in stressful situations without sufficient healthcare information and support. Healthcare providers should be aware of and understand the unmet needs of women. Tailored information should be given to individual women in collaboration between oncology and reproductive health providers to support them in maintaining hope and a positive mindset throughout the decision-making process about fertility issues. |

| Leflon et al. [46] | France | 2022 | To evaluate experiences and gynecological and reproductive health outcomes in women aged over 18 years at the time of FP who had undergone OTC prior to receiving moderate or highly gonadotoxic chemotherapy or radiotherapy for malignant or non-malignant disease. | Quantitative | Retrospective | 2019–2021 | Women who had undergone OTC (>18 months ago) before receiving moderate or highly gonadotoxic chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Aged over 18 at OTC. | 2004–2018 | Response rate: N = 64/87 (74%); Mean age at OTC: 30 years; Mean age at questionnaire: 35 years | Study specific questionnaire. All the questions had multiple-choice answers with a free-text option for additional explanatory notes | Young adult women expressed a good satisfaction rate with OTC. The majority of patients thought that OTC had a positive impact on their well-being during disease treatment. A reassuring effect on their future fertility was noted, as was the hope of having a child despite gonadotoxic treatment |

| Lewinsohn et al. [47] | USA and Canada | 2023 | To describe future desire for biological children, concerns about fertility, and the use of FP strategies among carriers and noncarriers. | Quantitative | Retrospective | 2006–2016 | Women newly diagnosed with breast cancer, aged ≤ 40 years; stage 0–IV breast cancer <6 months before enrolment. | 2006–2016 | Response rate: N = 1052/1302 (81%); 118 positives for germline pathogenic variant in cohort; Median age at diagnosis: 36 years in the carrier cohort, 37 years in the noncarrier cohort; Single diagnosis of breast cancer | Study specific questionnaire | A breast cancer diagnosis may alter some young women’s desire for children and give rise to concerns about future infertility, but this does not appear to be impacted by mutation status. The high level of reported concern about future children inheriting cancer risk among carriers highlights the importance of incorporating tailored, risk-mitigating recommendations during fertility counselling. |

| Melo et al. [48] | Portugal | 2018 | Understanding patients’ perceptions about the FP decision-making process and quality. To examine the association between the patients’ perceptions of healthcare providers’ support in the FP decision-making process and FP decision quality, and to determine whether this association differed based on the FP decision. | Quantitative | Prospective | 2013–2016 | Female patients aged between 18 and 40 years; recent diagnosis of cancer and a need to undergo gonadotoxic cancer therapy. | 2013–2016 | Response rate: N = 82/110 (76%) T1 (directly after FP counselling); Mean age: 31 years; Response rate: N = 71/82 (87%) T2 (after cancer treatment). Multiple diagnoses, i.a. breast cancer (75%) | Study specific questionnaire. At T1 patients’ perceptions of the FP decision-making process were assessed. At T2 the patients’ current perceptions of the decision-making process, their decisional regret and satisfaction with the decision were also included. | A less positive experience in the decision-making process was associated with higher decisional regret and lower decisional satisfaction. A higher quality decision was positively associated with a better experience in the decision-making process. The support of a health care provider is crucial for the decisional satisfaction of patients who opt not to pursue FP. |

| Mersereau et al. [49] | USA | 2013 | To identify factors associated with decisional conflict regarding FP using data from a prospective cohort study of reproductive outcomes in female young adult cancer survivors. | Quantitative | Cross sectional | 2011–2012 | Women aged 18 to 44 years at the time of study enrolment with a personal history of cancer. | Unclear | N = 208; Median age: 31 years at study survey; Median time since diagnosis: 2 years; Multiple diagnoses, i.a. breast cancer (32%) and Hodgkin’s lymphoma (20%) | Study specific questionnaire and a modified version of the DCS | Increasing access to FP via referral or counselling and cost reduction may decrease decisional conflict about FP for young patients struggling with cancer and fertility decisions. |

| Niemasik et al. [27] | USA | 2012 | To determine what women recalled about reproductive health risks (RHR) from cancer therapy at the time of cancer diagnosis in order to identify barriers to reproductive health counselling and FP. | Qualitative | Retrospective | 2010 | Women aged 18–40 years with a diagnosis of leukemia, Hodgkin’s disease, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, or breast or gastrointestinal cancer. | 1993–2007 | Response rate: N = 1041/2532 (41%) completed the survey and 697/2532 (28%) responded to the open-ended question; Mean age at diagnosis: 32 years; Mean age at survey: 41 years; Mean time since diagnosis: 10 years | Study specific questionnaire | Many women may not receive adequate information about reproductive health risks or FP at the time of their cancer diagnosis. Advancements in reproductive technology and emerging organizations that cover the financial costs of FP have dramatically broadened the options women have to preserve their fertility. Routine and thoughtful counselling, as well as collaborative cancer care, will help ensure that women diagnosed with cancer are provided with the services and information they need to make an informed choice about their reproductive future. |

| Ruddy et al. [50] | USA | 2014 | To better understand the burden of concern about fertility, how fertility concerns affect treatment decisions, and the FP strategies used by women in a large cohort of young women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. | Quantitative | Cross-sectional | 2006–2012 | Aged ≤ 40 years and diagnosis with stage 0 to IV breast cancer <6 months before enrolment between 2006 and 2012. | 2006–2012 | N = 620/1511 (41%); Median age: 37 years; Median time between diagnosis and return of baseline survey: 141.5 days. | Study specific questionnaire, and the modified Fertility Issues and Outcomes Scale (FIS) and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | Many young women with newly diagnosed breast cancer have concerns about their fertility, and for some, these substantially affect their treatment decisions. Not having children at diagnosis is associated with a greater likelihood of fertility concern |

| Ruggeri et al. [51] | Italy and Switzerland | 2019 | To characterize the experience of breast cancer in a cohort of young European women, focusing especially on fertility concerns and their impact on treatment decision making. | Quantitative | Cross-sectional | 2009–2016 | Aged ≤ 40 years with stage I-IV breast cancer, diagnosed < 6 months before enrolment (2009–2016). | 2009–2016 | N = 297/349 (85%) (207 from Italy, 90 from Switzerland); 32% of the women were aged < 35 years. | Study specific questionnaire a modified Fertility Issues Survey | Young women with newly diagnosed breast cancer have fertility concerns, including fear of increasing their personal or offspring cancer risk and not being able to take care of their children in case of disease relapse. In a multivariable analysis, having children was the only variable associated with fertility concerns. |

| Sauerbrun et al. [52] | USA | 2023 | To identify the prevalence and nature FP discussions and barriers to FP care. | Quantitative | Retrospective | 2019–2021 | Aged 18–42 years at time of breast cancer diagnosis. | 2006–2016 | N = 69/80 (86%) successfully contacted (322 eligible patients); Mean age at diagnosis unclear (70% between 35 and 42 years); Single diagnosis of breast cancer | Study specific questionnaire | Older women and those who were parents at the time of diagnosis were less likely to engage in a FP discussion. The most common reasons for declining FP consultation were already having their desired number of children, financial barriers, and concern about delaying cancer treatment and cancer recurrence. There was a higher proportion of FP discussions and consultation with a reproductive endocrinology and infertility specialist after 2013, when oocyte cryopreservation became non-experimental. |

| Schlossman et al. [68] | USA | 2023 | To identify the major barriers premenopausal individuals face in terms of accessing fertility care at the time of diagnosis with a gynecologic cancer, to assess patient experiences, particularly concerning fertility, and to learn how to better support such patients in the future. | Mixed methods | Retrospective | Unclear | Patients seen for follow up for ovarian, endometrial, or cervical cancer with no active cancer treatment. Aged 18–40 years at the time of diagnosis. | 2012–2022 | N = 55/228 (24%) completed questionnaires; Median age at diagnosis: 32 years; Multiple diagnoses of ovarian cancer (36%), endometrial cancer (22%), or cervical cancer (42%); N = 20 interviews; Median age at diagnosis: 32 years; Multiple diagnoses of ovarian cancer (50%), endometrial cancer (30%), and cervical cancer (20%) | Study specific questionnaire and semi-structured interview | Patients reported the emotional response of their diagnosis as a barrier to receiving fertility care, reporting lack of control and feelings of shock and confusion. Patients also identified inadequate counselling, a lack of time, economic constraints, and prioritization of cancer treatment as barriers. |

| Srikanthan et al. [28] | Canada | 2019 | To improve the information tools and decision aids available to women and to better understand patient experiences to improve the delivery of care. To understand patients’ experiences and attitudes regarding the delivery of care, fertility discussions, and FP at the time of initial diagnosis. | Qualitative | Retrospective | 2014 | Female breast cancer survivors, 39 years of age or younger at the time diagnosis, within 2 years of diagnosis (2012–2014). | 2012–2014 | N = 50/58 (86%); Median age: 35 years (range 25–39 years) | Semi-structured interview and four additional questions to elicit and quantify participant opinions on FP. | Six common themes: Requirement of more patient support; Improving information; Integration of patient values; Creating options for patients; Financial limitations; and The need to look beyond the immediate impact. |

| Urech et al. [53] | UK, USA, Switzerland, Germany and Austria | 2018 | To assess levels of knowledge concerning FP techniques and levels of confidence in that knowledge and attitudes toward FP. To assess differences concerning knowledge and attitudes between different language groups and healthcare systems and differences between participants who made use of any FP option compared to those who did not. | Quantitative | Retrospective | Unclear | Female cancer survivors aged ≥ 18 years who had a cancer diagnosis within the last 10 years and had a cancer therapy potentially affecting their reproductive function. | Unclear | N = 155 (80 English speaking countries and 75 in German speaking countries); mean age: 36 years (SD = 8 years); Unclear specific follow up time; Multiple cancer diagnoses, i.a. cervical cancer (45%), and breast cancer (30%) | A study specific web-based questionnaire | Knowledge about FP was limited among participants. Confidence of knowledge was significantly higher in women who had undergone any FP procedure. Greater emphasis should be placed on counselling opportunities and the provision of adequate information and support materials. |

| Van den Berg et al. [54] | The Netherlands | 2022 | To systematically assess the quality of integrated female oncofertility care by patient-reported measurement, to measure which determinants were associated with this quality of care, and to seek to develop tailored improvement strategies to improve the quality of integrated female oncofertility care. | Quantitative | Retrospective | 2020–2021 | Female AYA cancer patients 18 up to and including 40 years of age, diagnosed in 2016 or 2017 and received a (potentially) gonadotoxic treatment. | 2016–2017 | N = 121/344 (35%); Mean age: 34 years | Study specific questionnaire | Four determinants (patient age, strength of wish to conceive, time before cancer treatment, and type of health care provider) were found to be indicators on referral and shared decision making. Higher patient age was associated with lower referral rates. A higher wish to conceive was associated with higher referral rates and receiving written and/or digital information. |

| Vogt et al. [69] | UK | 2018 | To investigate factors influencing the decisions women with new diagnoses of cancer make about their fertility and to compare the quality of life, levels of anxiety, depression, illness perceptions, and optimism between women who chose to preserve their fertility and those who do not. | Mixed methods | Prospective | Unclear | Women (aged 16–40 years) with a new diagnosis of cancer and planned potentially gonadotoxic treatment (chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy). Group 1: from oncology who chose not to be referred to the assisted conception unit; Group 2: recruited from the ACU to see a fertility expert; Group 2A: those who made a positive FP decision; Group 2B: those who did not undergo FP. | Unclear | N: group 1 = 34; Mean age: 34 years; Multiple diagnoses, i.a. breast cancer (62%) and cervical cancer (21%); N: group 2 = 23; Mean age: 29 years; Multiple diagnoses, i.a. breast cancer (61%) and lymphoma (17%); Semi-structured interviews (group 2) N = 14/23 (61%); Mean age: 31 years; Multiple diagnoses, i.a. breast cancer (79%) | Questionnaires in two groups Group 1: Hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) and a short study-specific decision-making questionnaire (only ones) Group 2: 5 times during the car pathway to measure aspects of decision -making, patient satisfaction and HRQoL (validated questionnaires) and Semi-structured interviews to explore their experiences of the FP process. | Five themes were identified: Timing and quality of information provision Psychosocial factors Age Clinical influences Financial costs |

| Walasik [55] | Poland | 2023 | To assess the experience of Polish female cancer patients regarding FP after undergoing gonadotoxic treatment. | Quantitative | Retrospective | 2020 | Aged 18–50 years at the time of completing the survey, aged 10–40 at the time of malignancy diagnosis, diagnosis no more than 10 years before completing the questionnaire. | Unclear | N = 299; Multiple diagnoses, i.a. breast cancer (38%), Hodgkin lymphoma (22%) and thyroid cancer (9%) | Study specific questionnaire distributed via internet | More than half of the female subjects in this study did not undergo any pre-treatment FP counselling, although half of them had never been pregnant before the cancer diagnosis. Almost 30% claimed to have started the discussion. Around one third of the women had been referred to a fertility specialist, although only half of them visited the specialist. Half of the participants said that FP was not an important issue, instead seeing their oncological treatment as the highest priority. Women that were concerned about the negative influence of their cancer treatment on their fertility were more likely to use any form of FP. Only 17% of the participants did use some kind of FP. The study summarized reasons for not using FP and questions about the safety of having children after cancer treatment, as well as discussing the high cost of such treatment and the lack of knowledge thereof among some patients. |

| Von Wolff et al. [56] | Germany, Switzerland and Austria | 2016 | To assess patients’ attitudes about their fertility and about the counselling process at the time when FP counselling was performed | Quantitative | Cross-sectional | 2012–2013 | Female cancer patients aged 18–43 years, after FP counselling and before starting a gonadotoxic treatment. Patients were recruited in five centers belonging to the FertiPROTEKT network. | 2012–2013 | N = 144; Mean age: 30 years; Multiple diagnosis, i.a. breast cancer (54%) and lymphoma (22%) | Study specific questionnaire | As fertility concerns and attitudes about the counselling process were found to be independent of the chosen FP procedure, the preferred treatment can not accurately be predicted, and therefore, all women should be counselled about all possible FP techniques. Counselling by specialists about FP techniques is essential for all women undergoing gonadotoxic treatment, irrespective of whether they decide against or for a specific FP treatment. |

| Yee et al. [29] | Canada | 2012 | A survey of the views of female cancer survivors who sought an FP consultation prior to commencing cancer treatment. | Qualitative | Retrospective | Unclear | Female cancer patients referred to an IVF clinic for FP consultation between 2005 and 2008. | 2005–2008 | N = 41/70 (59%); Mean age: 33 years; Multiple diagnoses, i.a. breast cancer (76%), ovarian cancer (5%), and lymphoma (5%). | Study specific questionnaire The questionnaire also included five open-ended questions | It is important for oncology health care providers to initiate a discussion with all reproductive-age cancer patients. Timely referral to a fertility specialist is essential. It is beneficial to receive background information on FP options prior to the meeting with a fertility specialist. There is a lack of accessible and reliable cancer-related FP resources to reduce service barriers. Empathetic communication and flexibility in terms of accommodating fertility care needs are important. |

| Zanagnolo et al. [57] | Italy | 2005 | To evaluate the reproductive history, the experiences, attitudes, and emotions with regard to having children in conservatively treated patients with stage I epithelial ovarian cancer, any stage low malignant potential (LMP) tumors, malignant ovarian germ cell tumors (MOGCTs), or stage I sex cord-stromal tumors (SCSTs) | Quantitative | Retrospective | Unclear | Aged < 40 years at the time of diagnosis of stage I epithelial ovarian cancer, any stage low malignant potential (LMP) tumors where at least one of the ovaries was not or was only minimally involved, MOGCTs, or stage I SCSTs. Primary conservative surgical treatment, diagnosed between 1986 and 2000. | 1986–2000 | N = 41/68 returned questionnaires (60%); Mean age: 25 years at diagnosis; Median time of follow up: 102 months (35–192 months); Malignant ovarian tumors | Study specific questionnaire | Infertility has a strong potential to cause distress. Health care providers should be sensitized to the need to counsel patients proactively about reproductive issues. |

| Male | |||||||||||

| Achille et al. [30] | Canada | 2006 | To explore factors that facilitate or hinder sperm banking among survivors of testicular cancer and Hodgkin’s disease. | Qualitative | Retrospective | Unclear | Male patients aged 2–10 years post-diagnosis, being adult (age ≥ 18 years) at the time of diagnosis, having received chemotherapy alone or as part of a combination treatment for either testicular cancer or Hodgkin’s disease. | Unclear | N = 20; Mean age: 32 years at interview (27 years at diagnosis); Diagnosis of testicular cancer or Hodgkin’s disease | Semi-structured interviews | Six factors were identified as having an impact on sperm banking: the role of health care providers in discussing infertility and sperm banking, the importance survivors place on having biological children (and fatherhood status at the time of diagnosis), the influence of a parent or partner, attitudes toward survival at the time of diagnosis, the cost of sperm banking, and perceptions about the complexity and efficacy of sperm banking. |

| Chapple et al. [31] | UK | 2007 | To examine the experiences and perceptions of young men who have had cancer and who now have had to cope with fertility issues. | Qualitative | Retrospective | 2004–2005 | Male patients diagnosed with cancer. | Unclear | N = 18, 6 between 16–18 years at interview and 12 between 19–26 years at interview; Multiple but unclear diagnoses. | Semi-structured interviews | Four themes appeared to be salient to the young men interviewed: the importance of choice, the need for more counselling, concerns about sperm banking, and feelings about possible infertility. |

| Edge et al. [58] | UK | 2005 | To identify what proportion of patients was able to store semen and which factors affected their success of failure. | Quantitaive | Retrospective | 2001 | Male patients aged 13–21 years at the time of diagnosis. Diagnosed between 1997 and 2001. | 1997–2001 | Response rate: N = 45/55 completed questionnaires (82%); Multiple diagnoses, i.a. Hodgkin’s disease (27%), osteosarcoma (22%) and testicular tumors (16%); Mean age at time of diagnosis: 17 years; Average interval between diagnosis and completing the questionnaire: 2 years | Study specific online and additional focus-groups raising additional topics in face-to face discussions | The majority of adolescent cancer patients are able to store viable semen if offered the opportunity. Those who failed to bank sperm were younger, had greater levels of anxiety at diagnosis, and had more difficulty talking about fertility. Semen cryopreservation should be offered as a routine procedure to all sexually mature adolescents that are at risk of fertility impairment. |

| Ehrbar [70] | Switzerland | 2022 | To examine how male cancer patients experienced counselling and how helpful they perceived it to be. Their counselling needs were assessed and evaluated and they were asked whether an online support tool could be helpful. | Mixed Methods | Retrospective | Unclear | Men above 18 years of age with a cancer diagnosis within the last 10 years and 13 years or older at the time of diagnosis. | Unclear | Response rate: N = 72/149 completed online questionnaire (48%) and 12 were part of the following 3 focus-groups; Mean age: 33 years (31 years at diagnosis); Multiple diagnoses, i.a. testicular cancer (56%), Lymphoma (17%), and leukemia (14%) | Study specific online questionnaire and additional focus groups raising additional topics in face-to-face discussions | Cancer patients undergoing gonadotoxic therapy should be counselled about FP. Male participants appreciated a well-organized FP process. An online support tool that provides information about FP and general reproductive health was considered to be helpful. |

| Krouwel et al. [59] | The Netherlands | 2021 | A survey regarding patients’ experiences of discussions of fertility concerns and sperm preservation, the procedure of sperm cryopreservation, the number of children and the use of preserved samples, and satisfaction levels regarding information provision and reproductive concerns. | Quantitative | Retrospective | 2016 | Patients who were or had been in treatment at an outpatient clinic of the urology and/or oncology department of a university hospital between 1995–2015, with pathologically confirmed testicular cancer in their medical history, aged 18–70 years. | 1995–2015 | Response rate: N = 201/582 (35%); Mean age: 44 years; Mean age at diagnosis: 34 years; Follow up time: 11 years; Single diagnosis testicular cancer | Study specific questionnaire | A majority of respondents were notified about the possibility of fertility problems as a result of their treatment (88%). However, the possibility of sperm cryopreservation was discussed with only 77% of respondents. The reported levels of satisfaction with care could be directly correlated to the amount of information provided regarding fertility risks. |

| Latif and al. [32] | Pakistan | 2019 | To identify patient- and physician-related factors that influence decision about sperm banking in cancer patients, with particular emphasis on cultural aspects. | Qualitative study | Retrospective | Unclear | Male cancer patients aged 18–45 years, irrespective of cancer stage or type; semi structured interviews. | Unclear | Response rate: N = 25/31 (81%); Mean age: 31 years; Multiple diagnoses, i.a. Leukemia 40% and lymphoma 12% | Semi structured interviews | There is a significant lack of awareness among male cancer patients regarding infertility following cancer treatment. It is imperative that physicians inform them of this and discuss treatment options, along with addressing potential barriers. |

| Pacey [60] | UK | 2013 | To identify medical, demographic, and psychological variables on diagnosis (T1) and 1 year post-diagnosis (T2) which differentiate between bankers and non-bankers, and to determine health related quality of life among a sample of young men where treatment posed a risk to their fertility. | Quantitative | Prospective | 2008–2010 | Male cancer patients aged 18–45 years, diagnosed with either testicular cancer of a hematological disorder, good prognoses and undergoing treatment with curative intent. | 2008–2009 | Response rate: N = 91/105 (87%) (T1), 78/91 (86%) (T2); Mean age: 33 years; Two diagnoses, i.e., testicular cancer and hematological disorder | Multiple questionnaires: Health-related quality of life (QLQ-C30), Princess Margaret Hospital Patient Satisfaction with Doctor Questionnaire (PMH/PSQ-MD), Brief Illness perception questionnaire-revised (BIPQR) and study specific questionnaire | Patients who underwent sperm banking were younger and less likely to have children than non-bankers. Extra care should be taken when counselling younger men who may have given little consideration to future parenting. The results support a previous finding, i.e., that the role of a health care provider is vital in facilitating decisions, especially for those who are undecided about whether they want children in the future or not. |

| Perez et al. [61] | Canada | 2018 | To describe and examine the fertility-related informational needs of male cancer patients, to describe FP practices, as well as perceived barriers and facilitators to sperm banking among male cancer patients, and to examine if demographic characteristics were significantly related to fertility discussions and FP practices. | Quantitative | Retrospective | 2015–2016 | Male cancer patients aged 18–55 years. | Unclear | Response rate: N = 192/274 completed questionnaires (70%); Mean age: 34 years; Average age at cancer diagnosis: 30 years; Multiple diagnoses, i.a. lymphoma (40%), sarcoma (14%), and testicular cancer (14%) | Study specific questionnaire | Misconceptions about passing on cancer to one’s child and that sperm cryopreservation will delay treatment should be dispelled. Health care providers can ask patients if they have any desire to have children in the future as way to initiate a discussion about FP. Key information gaps and psychosocial resource needs are suggested to fully meet male cancer patients’ fertility-related concerns. |

| Schover et al. [62] | USA | 2002 | To confirm and elaborate the findings of a pilot study, i.e., that only 19% of men had banked sperm and that the most common reason for not banking was a lack of information. | Quantitative | Retrospective | Unclear | New diagnosis of cancer, aged 14 to 40 years. Treatment with chemotherapy, radiation to the whole body, pelvis, brain, or abdomen, or having intent to undergo pelvic surgery. | Unclear | Response rate: N = 201/904 completed questionnaires (22%); Mean age: 30 years; Response on average 3 years after cancer diagnosis; Multiple diagnoses, i.a. leukemia (24%), lymphoma, (26%) and testicular cancer (11%) | Study specific questionnaire | This study confirmed the importance of fatherhood to younger male cancer survivors. Over 50% of men would like to have a child in the future, including three quarters of men who were childless at diagnosis. |

| Xi et al. [63] | China | 2020 | To assess the awareness of fertility protection among patients and healthcare providers. | Quantitative | Retrospective | Unclear | Male cancer patients, aged 15–45 years. | Unclear | Response rate: N = 407/500 patients completed and returned questionnaire (81%); age during treatment and age since cancer diagnosis (unclear); Cancer type (unclear) | Study specific questionnaires | The awareness of reproductive protection among both physicians and cancer patients in Qingdao, China, was not satisfactory. There is a need for comprehensive health education and practical protocols. |

| Yee et al. [64] | Canada | 2012 | To explore factors associated with oncology patients’ decision to bank sperm prior to cancer treatment. | Quantitative | Cross-sectional | 2009–2010 | Patients referred for an oncology sperm banking program in the 2009–2010 period. | 2009–2010 | Response rate: N = 79/157 patients (50%); Mean age: 28.4 years; Multiple diagnoses, i.a. testicular cancer (35%), Hodgkin’s lymphoma (14%), and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (13%) | Study specific questionnaire, with more choice questions and some open-ended questions. | Two key determinants are associated with the sperm banking decisions: the physician’s recommendations and the patient’s desire for future fatherhood. |

| Zhang et al. [65] | China | 2020 | To explore the FP-related knowledge and needs of male cancer patients of reproductive age. | Quantitative | Cross-sectional | 2017–2018 | Male patients aged 18–45 years, on initial admission to the hospital and undergoing or already finished treatments that threaten fertility. | 2017–2018 | N = 332 patients completed the questionnaire; Mean age: 35.5 years; Multiple diagnoses, i.a. colorectal cancer (45%), malignant lymphoma (27%), and prostate cancer (23%) | Study specific questionnaire. | Knowledge about FP in male cancer survivors of reproductive age is generally poor. During treatment, some patients were interested in obtaining more information regarding FP. |

| Female and male | |||||||||||

| Anazodo et al. [33] | Australia | 2016 | To explore the experiences of consumers of oncofertility, to identify areas of oncofertility care needing development, and to develop a “charter” of the values and goals of consumers and health care providers regarding the gold standard in oncofertility care. | Qualitative | Retrospective | 2014–2015 | Pediatric, adolescent, and young adult cancer patients, completed treatment and in remission. | Unclear | N = 32, aged between 15–46 years, median age 22 years, 14 male, 18 female; Multiple diagnoses, i.a. Hodgkin’s lymphoma (22%), testicular cancer (16%), and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (16%). | Focus group discussion | Health care providers should discuss the possible effects of cancer treatment on a patient’s fertility before the start of treatment, irrespective of age, diagnosis, and prognosis of the patient. They should give patients an opportunity to discuss this by offering a referral to a fertility specialist. There should be a clear referral pathway to ensure that FP consultations can be organized in a timely manner. FP strategies should be affordable and equitable for all cancer patients. Psychosocial support should be available. |

| Armuand et al. [34] | Sweden | 2014 | To investigate newly diagnosed cancer patients’ experiences regarding fertility-related communication and their reasoning based on the risk of future infertility. | Qualitative | Cross-sectional | 2009–2011 | Patients aged 20–45 years, newly diagnosed with cancer (within a few weeks following diagnosis), planned treatment regarded as curative and with potential negative impact on fertility (2009–2011). | 2009–2011 | Response rate: N = 21/29 patients agreed to participate (72%); N = 11 women (median age 32 years) 10 men (median 33 year); Multiple diagnoses, i.a. lymphoma (24%), breast cancer (19%), and leukemia 19%) | Semi-structured interviews | Adequate information: very little, none, or only written fertility related information. Unmet informational needs about fertility preservation, as well as questions regarding the use of contraceptives during cancer treatment and how to check one’s fertility status after completed treatment. |

| Canzona et al. [35] | USA | 2021 | To construct a conceptual model of fertility concerns for AYAs. | Qualitative | Retrospective | Unclear | Patients diagnosed with cancer as an AYA, currently receiving treatment or within 5 years of completing treatment. | Unclear | N = 36 (Adolescents N = 10, mean age 17, Emerging adult N = 12, mean age 21, Young adult N = 14, mean age 33), 16 male, 20 female; Multiple diagnoses, i.a. leukemia (28%) and lymphoma (19%) | Semi-structured interviews | Four domains (affective, informational, coping, and logistical) of themes characterize fertility concerns among AYAs with cancer. AYA fertility and FP experiences were shaped by communication and timing factors. AYA fertility concerns are characterized by uncertainty and confusion that may contribute to future decisional regret or magnify feelings of loss. |

| Canzona et al. [36] | USA | 2023 | To explore ways in which AYAs with cancer may experience turning points throughout the FP decision making process, with a particular focus on differences between non-Hispanic White and racial/ethnic minority patients. | Qualitative | Retrospective | Unclear | Aged 15–39 years, currently receiving cancer treatment or within 5 years of concluding treatment. | Unclear | N = 36/68, 20 non-Hispanic White (11 men, 9 women, mean age 25 years), 16 racial/ethnic minority (5 men, 11 women, mean age 25%); Multiple diagnoses, i.a. leukemia (36%), Lymphoma (19%), and sarcoma (14%) | Semi-structured interviews (in person (N = 29) or via video/phone conference (N = 7) | Seven thematic turning points are described: (1) emotional reaction to discovering that FP procedures exist, (2) encountering unclear or dismissive communication during initial fertility conversations with health care providers, (3) encountering direct and supportive communication during initial fertility conversations with health care providers, (4) participating in critical family conversations about pursuing FP, (5) weighing personal desire for a child against other priorities/circumstances, (6) realizing that FP is not feasible, and (7) experiencing unanticipated changes in cancer diagnosis or treatment plans/procedures. Non-Hispanic white participants emphasized more forcefully that biological children may become a future priority. |

| Crawshaw et al. [37] | UK | 2009 | To investigate male and female adolescent cancer patients’ experiences in terms of fertility and associated decision-making matters being raised at diagnosis. | Qualitative | Retrospective | 2004–2006 | Diagnosed between 13–20 years or age, aware that fertility might have been affected and not receiving treatment. | Unclear | N = 38 (response rate of about 38%), 16 13–21 year-olds at interview (7 men, 9 women); median time since diagnosis: 3 years; 22 21–30 year-olds (12 women, 10 men); median time since diagnosis: 7 years); Multiple diagnoses, i.a. lymphoma (16%), leukemia (16%), and germ cell tumors (13%) | Semi-structured interviews | This study emphasizes the importance of addressing possible reproductive health implications at or around the time of diagnosis, even if options for fertility preservation are neither available nor appropriate, as well as the wish to have a choice in who should be included in these highly intimate discussions. |

| Kayiira et al. [66] | Uganda | 2022 | To establish the extent of self-reported reproductive failure associated with cancer treatment among AYA cancer survivors in Uganda and attitudes toward future fertility among AYA survivors of cancer. | Quantitative | Retrospective | Unclear | AYA survivors of cancer diagnosed between 2007 and 2018. At least 18 years of age, diagnosed with cancer between ages of 0 and 5 years. | 2007–2018 | N = 34, 14 females, 20 males; Median age at interview: 27 years (females) and 25 (males); Median age at diagnosis: 24 years (females) and 18 years (males); Multiple diagnoses, i.a. Kaposi’s sarcoma (44%), Burkitt lymphoma (9%), and Hodgkin’s lymphoma (6%) | Study specific telephonic interview questionnaire. | Information and counselling provided regarding therapy-related problems before cancer treatment was insufficient, reinforcing the need to build up the capacity for oncofertility resources within the region. |

| Levin et al. [38] | USA | 2023 | To explore the overall experiences of AYAs who encounter potential iatrogenic infertility and the ways in which financial concerns impact FP decision-making strategies. | Qualitative | Retrospective | 2019–2020 | Patients aged 12–25 years, diagnosed within the previous 2–12 months, at risk for infertility owing to diagnosis or prescribed curative treatment. | 2018–2020 | Response rate: N = 27/60 (45%), 17 males, 10 females; Multiple diagnoses, i.a. Hodgkin’s lymphoma (33%), synovial sarcoma (11%), and osteosarcoma (11%) | Semi-structured interview | Multiple and interrelated financial considerations factor into AYA experiences and decision making, including insurance coverage, presence of parental/guardian support, access to financial aid, negotiating potential risks, and consideration of long-term costs. |

| Marino et al. [67] | Australia | 2023 | To examine the perspectives of AYAs with cancer regarding the information they received about potential infertility and FP options and the decisions they made regarding their fertility. | Quantitative | Retrospective | 2010–2012 | 6–24 months after a diagnosis of cancer (including first diagnosis, relapse, or diagnosis of second cancer). | 2008–2012 | N = 196 returned completed surveys, 99 males (51%), 97 females (49%); Mean age at diagnosis: 20 years; mean age at survey completion: 22 years; Multiple diagnoses, i.a. malignant hematological diseases (31%), Hodgkin lymphoma (25%), and sarcoma (15%). | Study specific questionnaire | Family involvement in decision-making was considered helpful. Older patients were more likely than younger ones to have involved partners, although AYAs will be the main decision makers with regard to FP, particularly as AYAs mature. Resources and support should be available for patients’ parents, partners, and siblings. |

| Parton et al. [39] | Australia | 2019 | How do women and men construct and experience FP treatment? | Qualitative | Retrospective | Unclear | People with cancer and their partners responded to advertisements regarding fertility care after cancer. (See also study Ussher et al. [71]) | Unclear | Survey N = 693 women and 185 men; Average age: 43 years; average time from diagnosis: 6 years; Multiple diagnoses, i.a. breast cancer (57%), Gynecological cancer (13%), and hematologic cancer (13%); Interviews N = 61 women and 17 men; Mean age: 45 years | Survey with open answer questions and semi-structured telephone interviews | Three main discursive themes: limited agency and choice or resisting risk, FP as a means to retain hope and control, and FP as something that is uncertain and distressing. |