Quality of Life and Independent Factors Associated with Poor Digestive Function after Ivor Lewis Esophagectomy

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients, Own References, and EORTC Reference Cohort

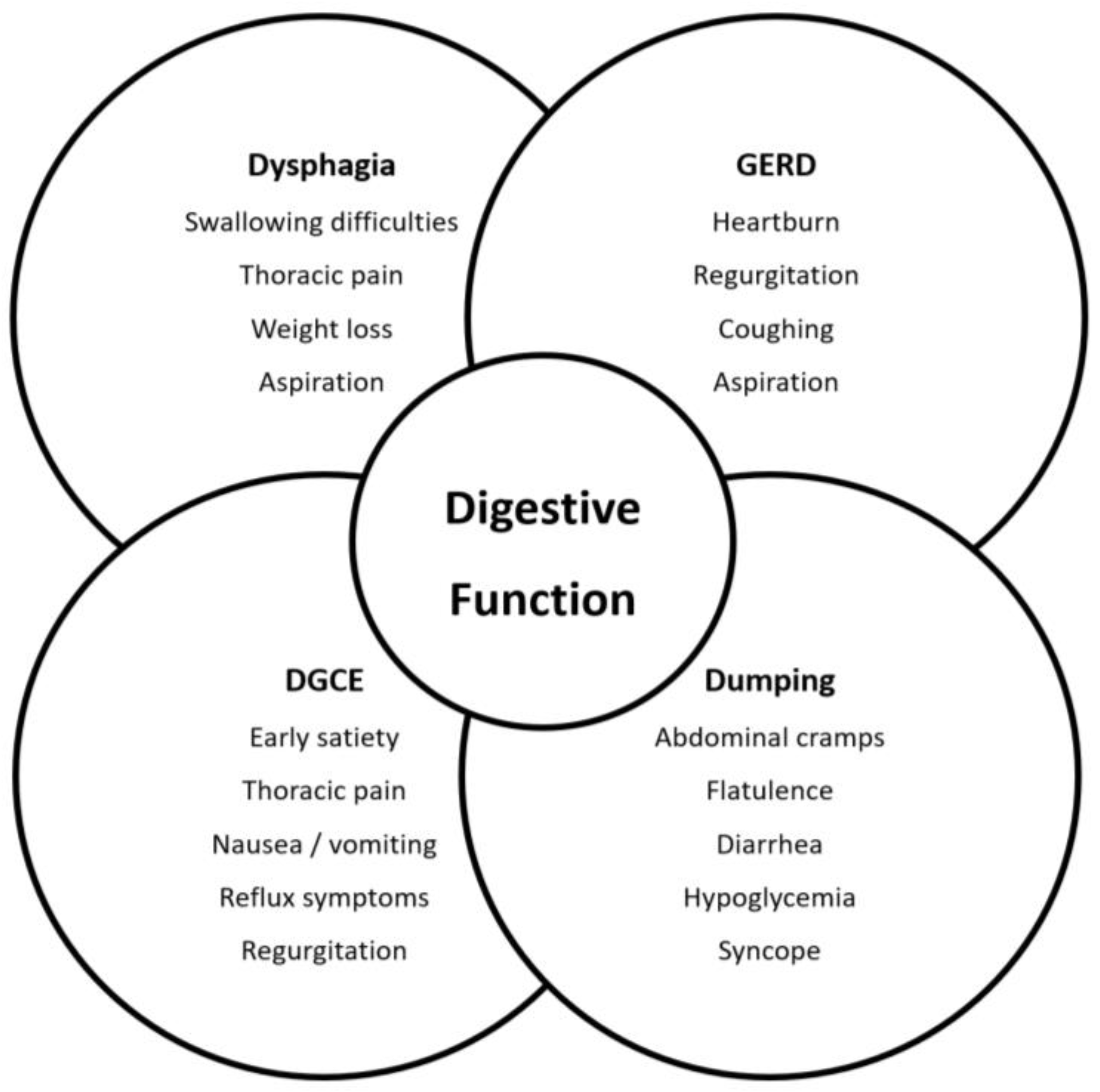

2.2. Assessment of Functional Syndromes and HRQL

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Basic Characteristics of Study Patients and Reference Cohorts

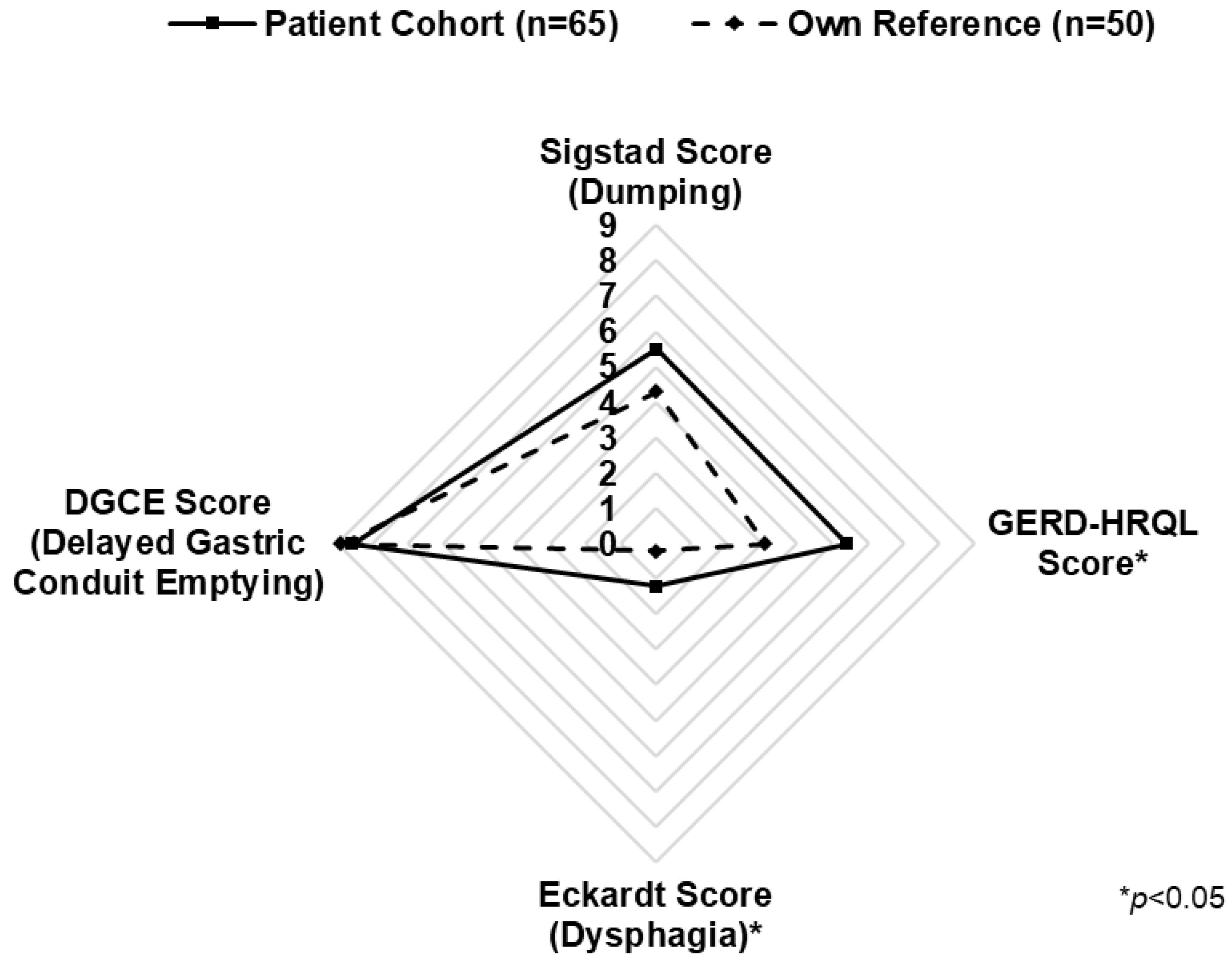

3.2. Functional Syndromes: Dysphagia, GERD, DGCE, and DS

3.3. General (EORTC QLQ C-30) and Esophagus-Specific (EORTC OES-18) HRQL

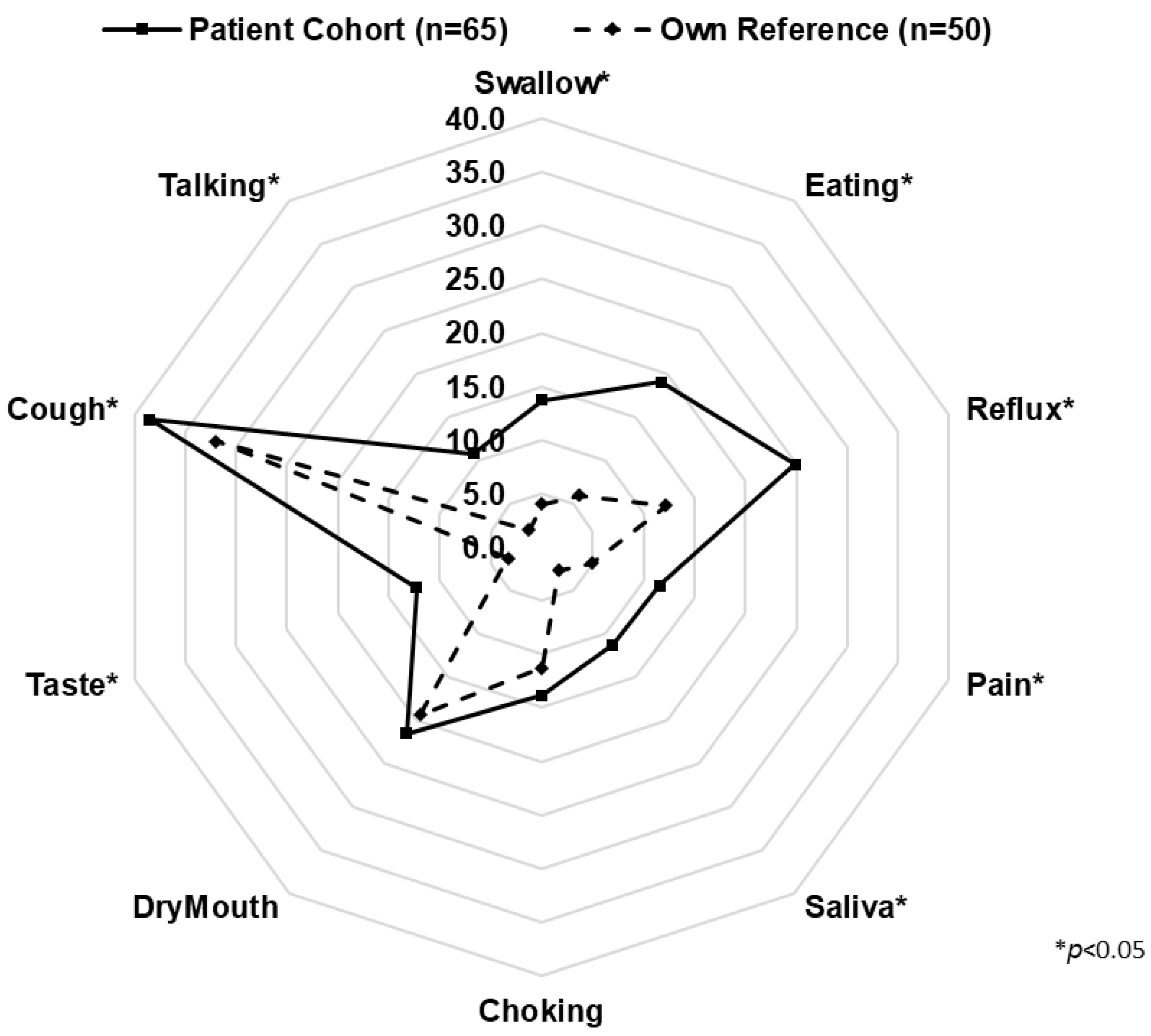

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration; Fitzmaurice, C.; Dicker, D.; Pain, A.; Hamavid, H.; Moradi-Lakeh, M.; MacIntyre, M.F.; Allen, C.; Hansen, G.; Woodbrook, R.; et al. The Global Burden of Cancer 2013. JAMA Oncol. 2015, 1, 505–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fransen, L.F.C.; Berkelmans, G.H.K.; Asti, E.; van Berge Henegouwen, M.I.; Berlth, F.; Bonavina, L.; Brown, A.; Bruns, C.; van Daele, E.; Gisbertz, S.S.; et al. The Effect of Postoperative Complications After Minimally Invasive Esophagectomy on Long-term Survival: An International Multicenter Cohort Study. Ann. Surg. 2021, 274, e1129–e1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, R.J.; Ajani, J.A.; Kuzdzal, J.; Zander, T.; Van Cutsem, E.; Piessen, G.; Mendez, G.; Feliciano, J.; Motoyama, S.; Lievre, A.; et al. Adjuvant Nivolumab in Resected Esophageal or Gastroesophageal Junction Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1191–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutschow, C.A.; Holscher, A.H.; Leers, J.; Fuchs, H.; Bludau, M.; Prenzel, K.L.; Bollschweiler, E.; Schroder, W. Health-related quality of life after Ivor Lewis esophagectomy. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2013, 398, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, H.; Holscher, A.H.; Leers, J.; Bludau, M.; Brinkmann, S.; Schroder, W.; Alakus, H.; Monig, S.; Gutschow, C.A. Long-term quality of life after surgery for adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction: Extended gastrectomy or transthoracic esophagectomy? Gastric. Cancer 2016, 19, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boshier, P.R.; Klevebro, F.; Savva, K.V.; Waller, A.; Hage, L.; Hanna, G.B.; Low, D.E. Assessment of Health Related Quality of Life and Digestive Symptoms in Long-term, Disease Free Survivors After Esophagectomy. Ann. Surg. 2022, 275, e140–e147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarpa, M.; Valente, S.; Alfieri, R.; Cagol, M.; Diamantis, G.; Ancona, E.; Castoro, C. Systematic review of health-related quality of life after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 17, 4660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukegjini, K.; Vetter, D.; Fehr, R.; Dirr, V.; Gubler, C.; Gutschow, C.A. Functional syndromes and symptom-orientated aftercare after esophagectomy. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2021, 406, 2249–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poghosyan, T.; Gaujoux, S.; Chirica, M.; Munoz-Bongrand, N.; Sarfati, E.; Cattan, P. Functional disorders and quality of life after esophagectomy and gastric tube reconstruction for cancer. J. Visc. Surg. 2011, 148, e327–e335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutschow, C.; Collard, J.-M.; Romagnoli, R.; Salizzoni, M.; Hölscher, A. Denervated Stomach as an Esophageal Substitute Recovers Intraluminal Acidity with Time. Ann. Surg. 2001, 233, 509–514. [Google Scholar]

- Deldycke, A.; Van Daele, E.; Ceelen, W.; Van Nieuwenhove, Y.; Pattyn, P. Functional outcome after Ivor Lewis esophagectomy for cancer. J. Surg. Oncol. 2016, 113, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donington, J.S. Functional Conduit Disorders After Esophagectomy. Thorac. Surg. Clin. 2006, 16, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maas, K.W.; Cuesta, M.A.; Van Berge Henegouwen, M.I.; Roig, J.; Bonavina, L.; Rosman, C.; Gisbertz, S.S.; Biere, S.S.A.Y.; Van Der Peet, D.L. Quality of Life and Late Complications After Minimally Invasive Compared to Open Esophagectomy: Results of a Randomized Trial. World J. Surg. 2015, 39, 1986–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbour, A.P.; Cormack, O.M.M.; Baker, P.J.; Hirst, J.; Krause, L.; Brosda, S.; Thomas, J.M.; Blazeby, J.M.; Thomson, I.G.; Gotley, D.C.; et al. Long-term Health-related Quality of Life Following Esophagectomy. Ann. Surg. 2017, 265, 1158–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Klevebro, F.; Kauppila, J.H.; Markar, S.; Johar, A.; Lagergren, P. Health-related quality of life following total minimally invasive, hybrid minimally invasive or open oesophagectomy: A population-based cohort study. Br. J. Surg. 2020, 108, 702–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, I. The surgical treatment of carcinoma of the oesophagus; with special reference to a new operation for growths of the middle third. Br. J. Surg. 1946, 34, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EORTC: European Organisation for Cancer and Treatment. EORTC QLQ-C30 Reference Values. Available online: https://www.eortc.org/app/uploads/sites/2/2018/02/reference_values_manual2008.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Eckardt, V.F.; Aignherr, C.; Bernhard, G. Predictors of outcome in patients with achalasia treated by pneumatic dilation. Gastroenterology 1992, 103, 1732–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velanovich, V. The development of the GERD-HRQL symptom severity instrument. Dis. Esophagus 2007, 20, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konradsson, M.; van Berge Henegouwen, M.I.; Bruns, C.; Chaudry, M.A.; Cheong, E.; Cuesta, M.A.; Darling, G.E.; Gisbertz, S.S.; Griffin, S.M.; Gutschow, C.A.; et al. Diagnostic criteria and symptom grading for delayed gastric conduit emptying after esophagectomy for cancer: International expert consensus based on a modified Delphi process. Dis. Esophagus 2020, 33, doz074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigstad, H. Post-gastrectomy radiology with a physiologic contrast medium: Comparison between dumpers and non-dumpers. Br. J. Radiol. 1971, 44, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaronson, N.K.; Ahmedzai, S.; Bergman, B.; Bullinger, M.; Cull, A.; Duez, N.J.; Filiberti, A.; Flechtner, H.; Fleishman, S.B.; de Haes, J.C.; et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1993, 85, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blazeby, J.M.; Conroy, T.; Hammerlid, E.; Fayers, P.; Sezer, O.; Koller, M.; Arraras, J.; Bottomley, A.; Vickery, C.W.; Etienne, P.L.; et al. Clinical and psychometric validation of an EORTC questionnaire module, the EORTC QLQ-OES18, to assess quality of life in patients with oesophageal cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2003, 39, 1384–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fayers, P.; Bottomley, A. Quality of life research within the EORTC-the EORTC QLQ-C30. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2002, 38 (Suppl. S4), S125–S133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagergren, P.; Johar, A.; Rosenlund, H.; Arnberg, L.; Haglund, L.; Ness-Jensen, E.; Schandl, A. Severe reflux, sleep disturbances, and health-related quality of life after esophageal cancer surgery. J. Cancer Surviv. 2021, 15, 818–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djärv, T.; Lagergren, P. Quality of life after esophagectomy for cancer. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 6, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, J.V.; McLaughlin, R.; Moore, J.; Rowley, S.; Ravi, N.; Byrne, P.J. Prospective evaluation of quality of life in patients with localized oesophageal cancer treated by multimodality therapy or surgery alone. Br. J. Surg. 2006, 93, 1084–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blazeby, J.M.; Farndon, J.R.; Donovan, J.; Alderson, D. A prospective longitudinal study examining the quality of life of patients with esophageal carcinoma. Cancer 2000, 88, 1781–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, A.G.; van Lanschot, J.J.; van Sandick, J.W.; Hulscher, J.B.; Stalmeier, P.F.; de Haes, J.C.; Tilanus, H.W.; Obertop, H.; Sprangers, M.A. Quality of life after transhiatal compared with extended transthoracic resection for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 4202–4208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallin, F.; Pinto, E.; Saadeh, L.M.; Alfieri, R.; Cagol, M.; Castoro, C.; Scarpa, M. Health related quality of life after oesophagectomy: Elderly patients refer similar eating and swallowing difficulties than younger patients. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, C.L.; DeMeester, S.R.; Worrell, S.G.; Oh, D.S.; Hagen, J.A.; DeMeester, T.R. Alimentary satisfaction, gastrointestinal symptoms, and quality of life 10 or more years after esophagectomy with gastric pull-up. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2014, 147, 909–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schandl, A.; Lagergren, J.; Johar, A.; Lagergren, P. Health-related quality of life 10 years after oesophageal cancer surgery. Eur. J. Cancer 2016, 69, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Däster, S.; Soysal, S.D.; Stoll, L.; Peterli, R.; von Flüe, M.; Ackermann, C. Long-term quality of life after Ivor Lewis esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. World J. Surg. 2014, 38, 2345–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantoan, S.; Cavallin, F.; Pinto, E.; Saadeh, L.M.; Alfieri, R.; Cagol, M.; Bellissimo, M.C.; Castoro, C.; Scarpa, M. Long-term quality of life after esophagectomy with gastric pull-up. J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 117, 970–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, M.T.Y.; Tsang, R.K.; Wong, I.Y.H.; Chan, D.K.K.; Chan, F.S.Y.; Law, S.Y.K. Long-term pharyngeal dysphagia after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer-an investigation using videofluoroscopic swallow studies. Dis. Esophagus 2019, 32, doy068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donohoe, C.L.; McGillycuddy, E.; Reynolds, J.V. Long-term health-related quality of life for disease-free esophageal cancer patients. World J. Surg. 2011, 35, 1853–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohoe, C.L.; Reynolds, J.V. Defining a successful esophagectomy. Ann. Surg. 2014, 259, e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wen, S.; Lv, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Mu, D.; Tian, Z. Comparison of Up-Front Minimally Invasive Esophagectomy versus Open Esophagectomy on Quality of Life for Esophageal Squamous Cell Cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2021, 28, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straatman, J.; van der Wielen, N.; Cuesta, M.A.; Daams, F.; Roig Garcia, J.; Bonavina, L.; Rosman, C.; van Berge Henegouwen, M.I.; Gisbertz, S.S.; van der Peet, D.L. Minimally Invasive Versus Open Esophageal Resection: Three-year Follow-up of the Previously Reported Randomized Controlled Trial: The TIME Trial. Ann. Surg. 2017, 266, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backemar, L.; Wikman, A.; Djärv, T.; Johar, A.; Lagergren, P. Co-morbidity after oesophageal cancer surgery and recovery of health-related quality of life. Br. J. Surg. 2016, 103, 1665–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klevebro, F.; Johar, A.; Lagergren, P. Impact of co-morbidities on health-related quality of life 10 years after surgical treatment of oesophageal cancer. BJS Open 2020, 4, 601–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Patient Cohort (n = 65) | Own Reference (n = 50) | EORTC Reference (n = 7802) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years median (IQR) | 71 1 (64–77) | 65 (58–71) | 40–80 years |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 54 (83) | 23 (46) | 4057 (52) |

| Female | 21 (17) | 27 (54) | 3745 (48) |

| BMI median (IQR) | 25.7 (24.2–28.5) | 24.4 (22.6–28.4) | |

| Performance status | |||

| ASA 1 and ECOG 0 | 1 (2) | 50 (100) | |

| ASA ≥ 2 and/or ECOG ≥ 1 | 64 (98) | ||

| Tumor histology | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 42 (65) | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 16 (25) | ||

| Other | 7 (10) | ||

| Pathological tumor stage (n = 62) | |||

| UICC 0 | 8 (13) | ||

| UICC I | 12 (19) | ||

| UICC II | 10 (15) | ||

| UICC III | 28 (46) | ||

| UICC IV | 4 (7) | ||

| Neoadjuvant treatment | |||

| None | 21 (32) | ||

| Chemotherapy | 8 (12) | ||

| Chemoradiotherapy | 36 (56) | ||

| Adjuvant treatment | |||

| None | 51 (78) | ||

| Chemotherapy | 12 (18) | ||

| Chemoradiotherapy | 1 (2) | ||

| Radiotherapy | 1 (2) | ||

| Follow-up time months | |||

| Median (IQR) | 29 (18–49) | ||

| <36 months | 35 (54) | ||

| ≥36 months | 30 (46) | ||

| Surgical access | |||

| Total MIS | 48 (74) | ||

| Hybrid | 13 (20) | ||

| Open | 4 (6) | ||

| 90-day readmission | |||

| Yes | 5 (8) | ||

| No | 60 (92) | ||

| CCI at discharge median (IQR) | 20.9 (0–29.6) |

| Characteristic | Variable | Average Score Increase or Decrease | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| EORTC QLQ-C30 1 | ASA score | Decrease of 18.7–32.4 points | 0.04 |

| EORTC QLQ-C30 1 | ICU readmission | Decrease of 34.7 points | <0.01 |

| EORTC QLQ-C30 1 | Squamous cell carcinoma | Decrease of 7.5 points | <0.01 |

| EORTC QLQ-C30 1 | Adjuvant chemotherapy | Decrease of 19.4 points | <0.01 |

| EORTC QLQ-C30 1 | Hybrid surgical access | Decrease of 11.4 points | <0.01 |

| EORTC QLQ OES-18 | Squamous cell carcinoma | Increase of 6.8 points | 0.02 |

| EORTC QLQ OES-18 | Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | Increase of 14.1 points | 0.02 |

| EORTC QLQ OES-18 | Hybrid surgical access | Increase of 8.7 points | 0.02 |

| EORTC QLQ OES-18 | Open surgical access | Increase of 31.1 points | <0.01 |

| Eckardt (Dysphagia) | ASA score | Increase of 3 points | 0.02 |

| GERD-HRQL | Open surgical access | Increase of 12.8 points | 0.01 |

| GERD-HRQL | Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | Increase of 8.8 points | 0.03 |

| DGCE | Open surgical access | Increase of 4.9 points | 0.04 |

| Sigstad (Dumping) | None | - | None |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dirr, V.; Vetter, D.; Sartoretti, T.; Schneider, M.A.; Da Canal, F.; Gutschow, C.A. Quality of Life and Independent Factors Associated with Poor Digestive Function after Ivor Lewis Esophagectomy. Cancers 2023, 15, 5569. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15235569

Dirr V, Vetter D, Sartoretti T, Schneider MA, Da Canal F, Gutschow CA. Quality of Life and Independent Factors Associated with Poor Digestive Function after Ivor Lewis Esophagectomy. Cancers. 2023; 15(23):5569. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15235569

Chicago/Turabian StyleDirr, Valerian, Diana Vetter, Thomas Sartoretti, Marcel André Schneider, Francesca Da Canal, and Christian A. Gutschow. 2023. "Quality of Life and Independent Factors Associated with Poor Digestive Function after Ivor Lewis Esophagectomy" Cancers 15, no. 23: 5569. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15235569

APA StyleDirr, V., Vetter, D., Sartoretti, T., Schneider, M. A., Da Canal, F., & Gutschow, C. A. (2023). Quality of Life and Independent Factors Associated with Poor Digestive Function after Ivor Lewis Esophagectomy. Cancers, 15(23), 5569. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15235569