Administration of Enfortumab Vedotin after Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitor and the Prognosis in Japanese Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma: A Large Database Study on Enfortumab Vedotin in Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

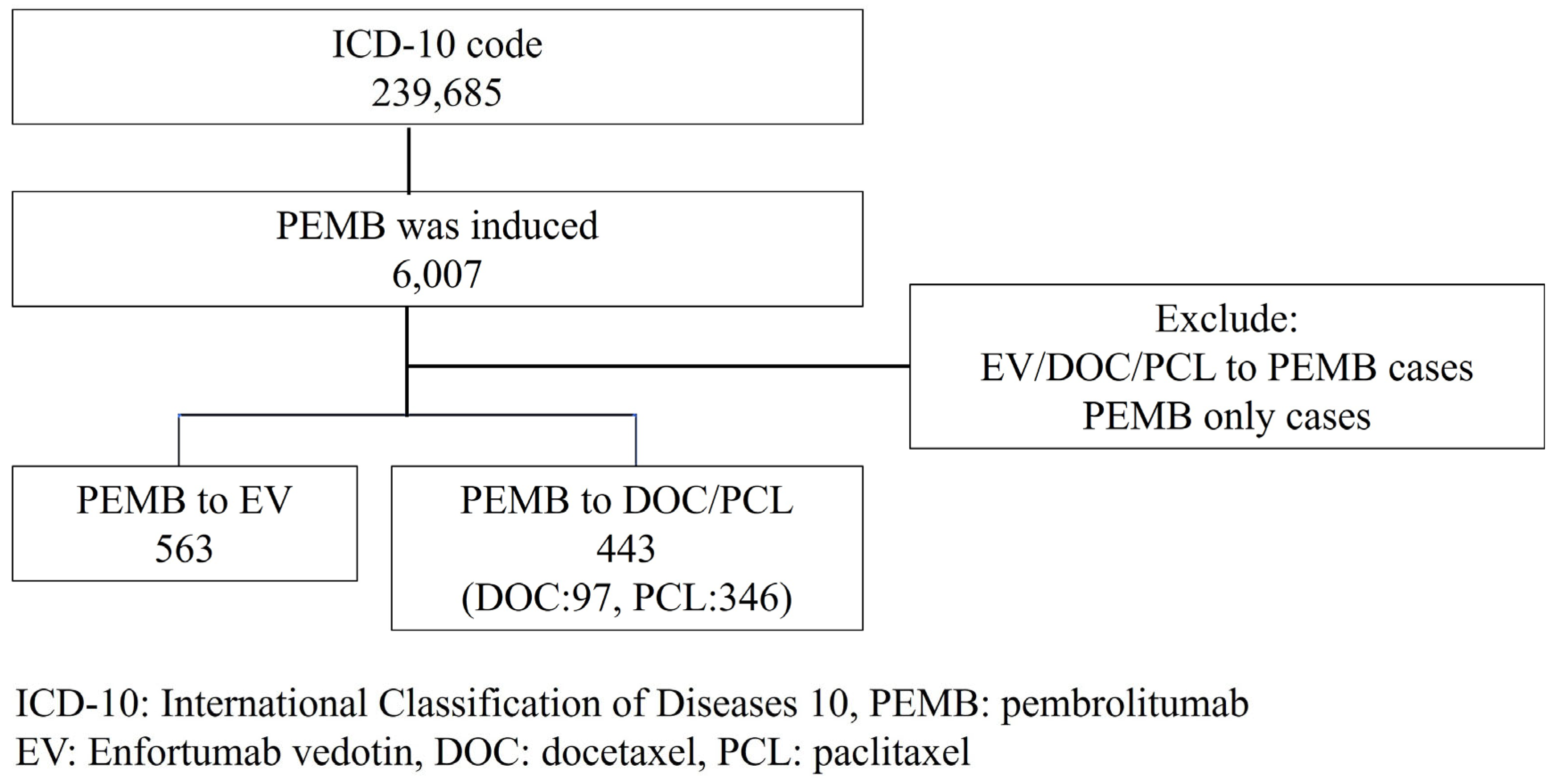

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analyses

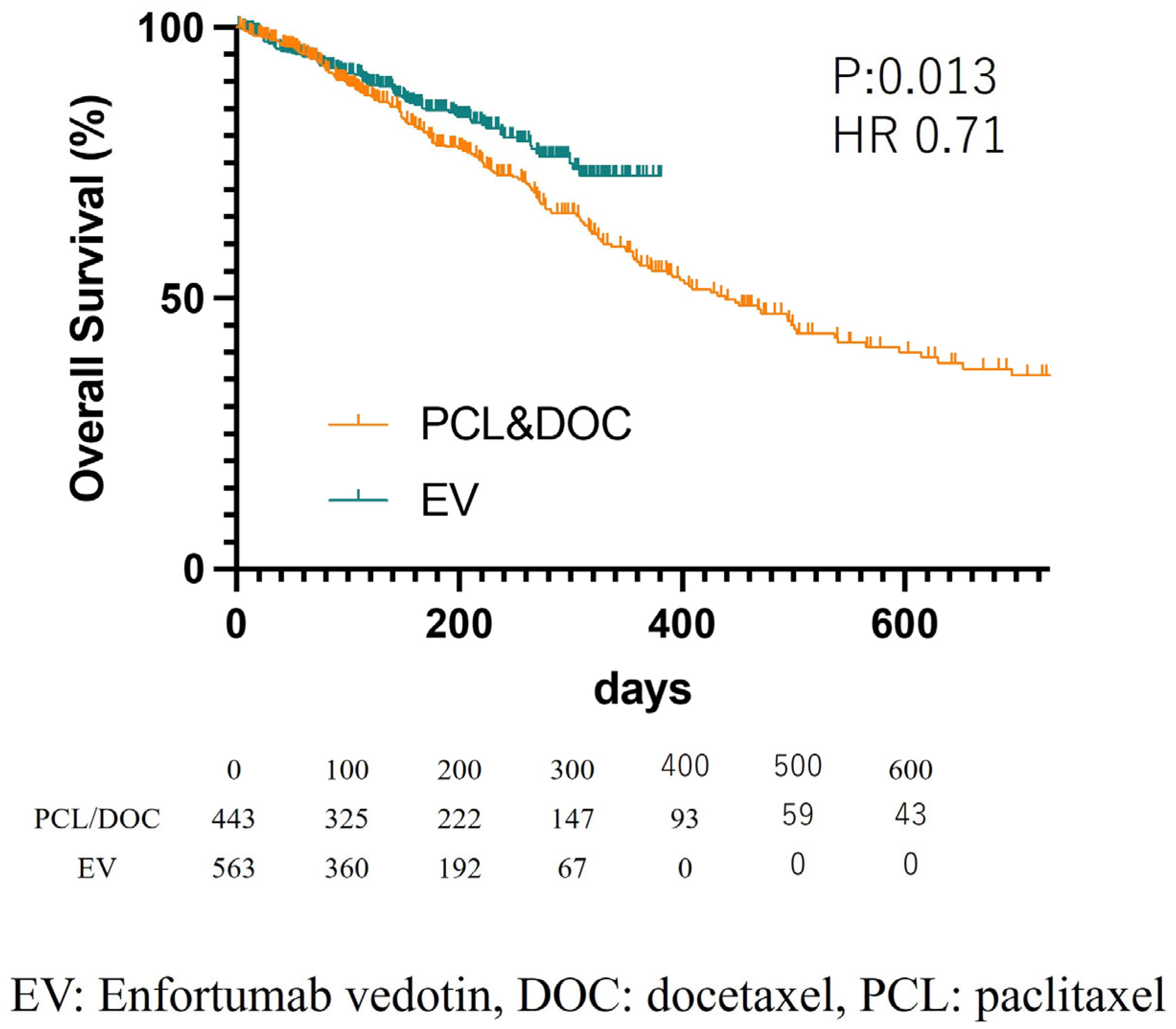

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alimohamed, N.; Grewal, S.; Wirtz, H.S.; Hepp, Z.; Sauvageau, S.; Boyne, D.J.; Brenner, D.R.; Cheung, W.Y.; Jarada, T.N. Understanding Treatment Patterns and Outcomes among Patients with De Novo Unresectable Locally Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Cancer: A Population-Level Retrospective Analysis from Alberta, Canada. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 7587–7597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torre, L.A.; Bray, F.; Siegel, R.L.; Ferlay, J.; Lortet-Tieulent, J.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2015, 65, 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witjes, J.A.; Lebret, T.; Compérat, E.M.; Cowan, N.C.; De Santis, M.; Bruins, H.M.; Hernández, V.; Espinós, E.L.; Dunn, J.; Rouanne, M.; et al. Updated 2016 EAU Guidelines on Muscle-Invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2017, 71, 462–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maas, M.; Stühler, V.; Walz, S.; Stenzl, A.; Bedke, J. Enfortumab vedotin—Next game-changer in urothelial cancer. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2021, 21, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellmunt, J.; De Wit, R.; Vaughn, D.J.; Fradet, Y.; Lee, J.-L.; Fong, L.; Vogelzang, N.J.; Climent, M.A.; Petrylak, D.P.; Choueiri, T.K.; et al. Pembrolizumab as Second-Line Therapy for Advanced Urothelial Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koshkin, V.S.; Henderson, N.; James, M.; Natesan, D.; Freeman, D.; Nizam, A.; Su, C.T.; Khaki, A.R.; Osterman, C.K.; Glover, M.J.; et al. Efficacy of enfortumab vedotin in advanced urothelial cancer: Analysis from the Urothelial Cancer Network to Investigate Therapeutic Experiences (UNITE) study. Cancer 2022, 128, 1194–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powles, T.; Rosenberg, J.E.; Sonpavde, G.P.; Loriot, Y.; Durán, I.; Lee, J.-L.; Matsubara, N.; Vulsteke, C.; Castellano, D.; Wu, C.; et al. Enfortumab Vedotin in Previously Treated Advanced Urothelial Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1125–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, J.E.; O’Donnell, P.H.; Balar, A.V.; McGregor, B.A.; Heath, E.I.; Yu, E.Y.; Galsky, M.D.; Hahn, N.M.; Gartner, E.M.; Pinelli, J.M.; et al. Pivotal Trial of Enfortumab Vedotin in Urothelial Carcinoma after Platinum and Anti-Programmed Death 1/Programmed Death Ligand 1 Therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 2592–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, E.Y.; Petrylak, D.P.; O’Donnell, P.H.; Lee, J.L.; van der Heijden, M.S.; Loriot, Y.; Stein, M.N.; Necchi, A.; Kojima, T.; Harrison, M.R.; et al. Enfortumab vedotin after PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitors in cisplatin-ineligible patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma (EV-201): A multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 872–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsubara, N.; Yonese, J.; Kojima, T.; Azuma, H.; Matsumoto, H.; Powles, T.; Rosenberg, J.E.; Petrylak, D.P.; Matsangou, M.; Wu, C.; et al. Japanese subgroup analysis of EV-301: An open-label, randomized phase 3 study to evaluate enfortumab vedotin versus chemotherapy in subjects with previously treated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 2761–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawahara, T.; Miyoshi, Y.; Ninomiya, S.; Sato, M.; Takeshima, T.; Hasumi, H.; Makiyama, K.; Uemura, H. Administration of radium-223 and the prognosis in Japanese bone metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer patients: A large database study. Int. J. Urol. 2022, 29, 1079–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Challita-Eid, P.M.; Satpayev, D.; Yang, P.; An, Z.; Morrison, K.; Shostak, Y.; Raitano, A.; Nadell, R.; Liu, W.; Lortie, D.R.; et al. Enfortumab Vedotin Antibody-Drug Conjugate Targeting Nectin-4 Is a Highly Potent Therapeutic Agent in Multiple Preclinical Cancer Models. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 3003–3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Shen, Q.; Yin, W.; Huang, H.; Liu, Y.; Ni, Q. High expression of Nectin-4 is associated with unfavorable prognosis in gastric cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 15, 8789–8795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raggi, D.; Miceli, R.; Sonpavde, G.; Giannatempo, P.; Mariani, L.; Galsky, M.D.; Bellmunt, J.; Necchi, A. Second-line single-agent versus doublet chemotherapy as salvage therapy for metastatic urothelial cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Oncol. 2016, 27, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powles, T.; Park, S.H.; Voog, E.; Caserta, C.; Valderrama, B.P.; Gurney, H.; Kalofonos, H.; Radulović, S.; Demey, W.; Ullén, A.; et al. Avelumab Maintenance Therapy for Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1218–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Number (%), Median (Mean ± SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALL | PCL/DOC | EV | p-Value (PCL/DOC vs. EV) | |

| Number of patients | 1006 | 443 (PCL346/DOC97) | 563 | |

| Male | 784 (77.9%) | 350 (79.0%) | 434 (77.1%) | 0.466 |

| Age 70 or more (yrs.) | 540 (53.7%) | 235 (53.0%) | 305 (54.2%) | 0.772 |

| Age at diagnosis (yrs.) | 70 (69.2 ± 8.4) | 70 (69.0 ± 8.5) | 70 (69.4 ± 8.2%) | 0.434 |

| Age at each treatment (yrs.) | 73 (71.8 ± 9.0) | 73 (71.4 ± 9.9) | 73 (72.2 ± 8.3) | 0.187 |

| Location | ||||

| Bladder | 615 (61.1%) | 279 (63.0%) | 336 (59.7%) | 0.287 |

| Ureter | 231 (23.0%) | 98 (22.1%) | 133 (23.6%) | 0.574 |

| Renal Pelvis | 255 (25.3%) | 108 (24.3%) | 147 (26.1%) | 0.531 |

| Previous cystectomy | 145 (14.4%) | 49 (11.1%) | 96 (17.1%) | 0.007 |

| Previous chemotherapy | ||||

| Gemcitabine | 835 (83.0%) | 318 (71.8%) | 517 (91.8%) | <0.001 |

| Cisplatin | 571 (56.8%) | 217 (48.9%) | 354 (62.9%) | <0.001 |

| Carboplatin | 508 (50.5%) | 235 (53.0%) | 234 (41.5%) | <0.001 |

| Methotrexate | 48 (4.8%) | 24 (5.4%) | 23 (4.3%) | 0.320 |

| Pembrolizumab | 1006 (100.0%) | 443 (100.0%) | 563 (100.0%) | 1.000 |

| Variables | HR | 95% CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Age 70 yrs. and over | 0.87 | 0.68 | 1.11 | 0.266 |

| Male | 1.05 | 0.77 | 1.44 | 0.749 |

| Bladder cancer | 0.84 | 0.64 | 1.09 | 0.191 |

| EV induction | 0.70 | 0.53 | 0.93 | 0.013 |

| Cystectomy | 1.11 | 0.76 | 1.62 | 0.597 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kawahara, T.; Hasizume, A.; Uemura, K.; Yamaguchi, K.; Ito, H.; Takeshima, T.; Hasumi, H.; Teranishi, J.-i.; Ousaka, K.; Makiyama, K.; et al. Administration of Enfortumab Vedotin after Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitor and the Prognosis in Japanese Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma: A Large Database Study on Enfortumab Vedotin in Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma. Cancers 2023, 15, 4227. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15174227

Kawahara T, Hasizume A, Uemura K, Yamaguchi K, Ito H, Takeshima T, Hasumi H, Teranishi J-i, Ousaka K, Makiyama K, et al. Administration of Enfortumab Vedotin after Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitor and the Prognosis in Japanese Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma: A Large Database Study on Enfortumab Vedotin in Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma. Cancers. 2023; 15(17):4227. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15174227

Chicago/Turabian StyleKawahara, Takashi, Akihito Hasizume, Koichi Uemura, Katsuya Yamaguchi, Hiroki Ito, Teppei Takeshima, Hisashi Hasumi, Jun-ichi Teranishi, Kimito Ousaka, Kazuhide Makiyama, and et al. 2023. "Administration of Enfortumab Vedotin after Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitor and the Prognosis in Japanese Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma: A Large Database Study on Enfortumab Vedotin in Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma" Cancers 15, no. 17: 4227. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15174227

APA StyleKawahara, T., Hasizume, A., Uemura, K., Yamaguchi, K., Ito, H., Takeshima, T., Hasumi, H., Teranishi, J.-i., Ousaka, K., Makiyama, K., & Uemura, H. (2023). Administration of Enfortumab Vedotin after Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitor and the Prognosis in Japanese Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma: A Large Database Study on Enfortumab Vedotin in Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma. Cancers, 15(17), 4227. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15174227