The Clinical Characteristics and Treatments for Large Cell Carcinoma Patients Older than 65 Years Old: A Population-Based Study

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Data Source

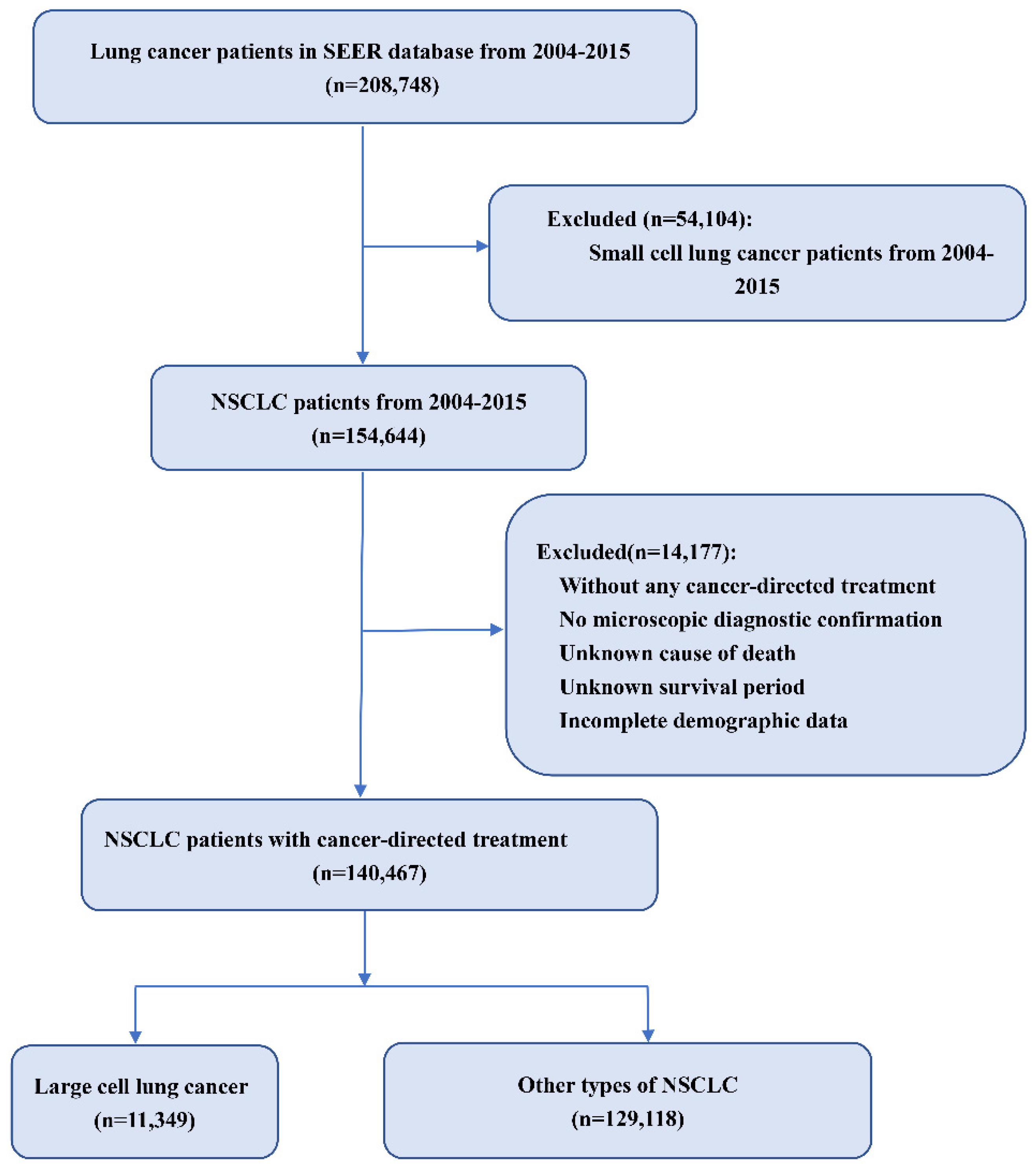

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Data Elements

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Cohort Characteristics

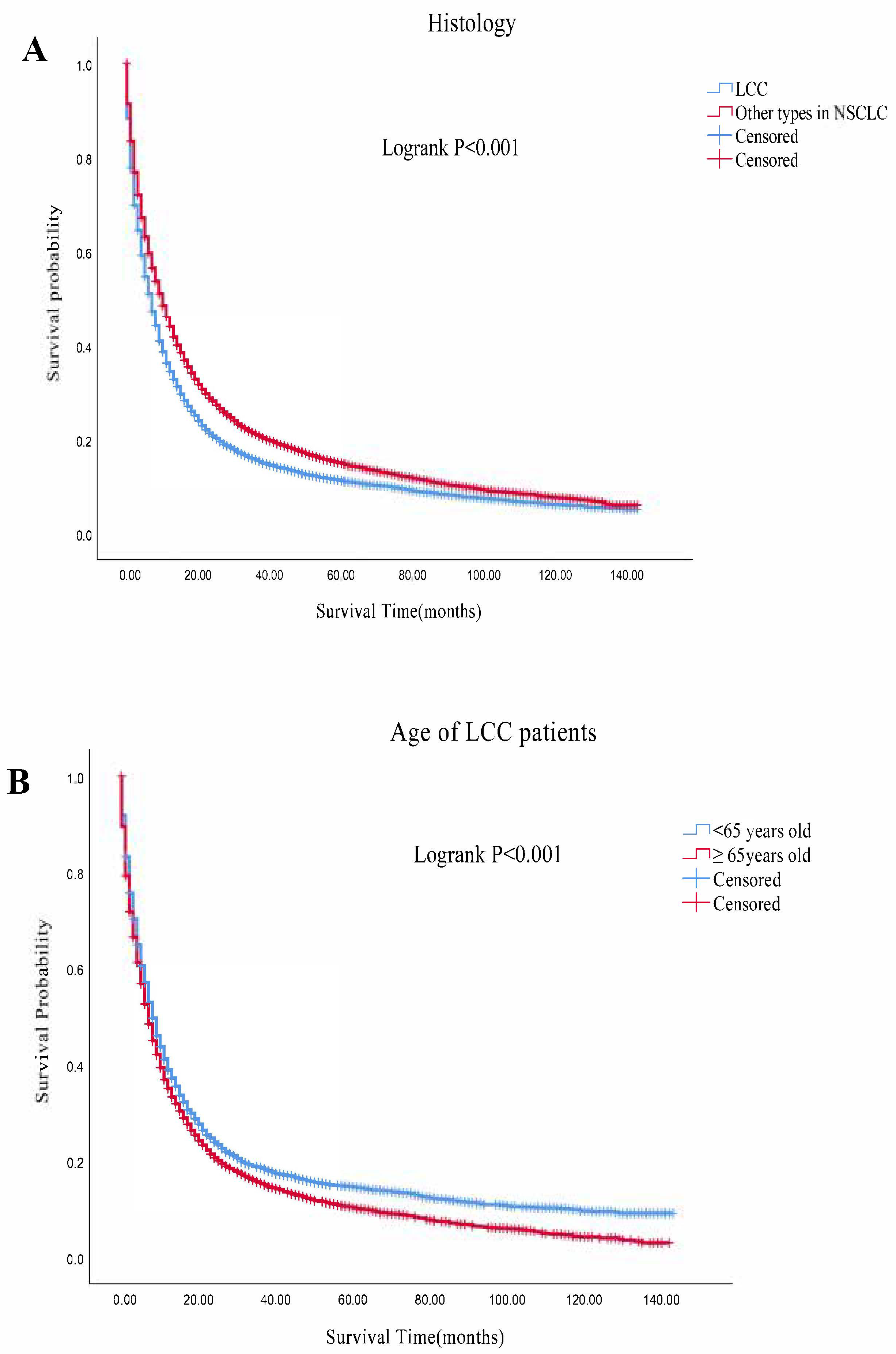

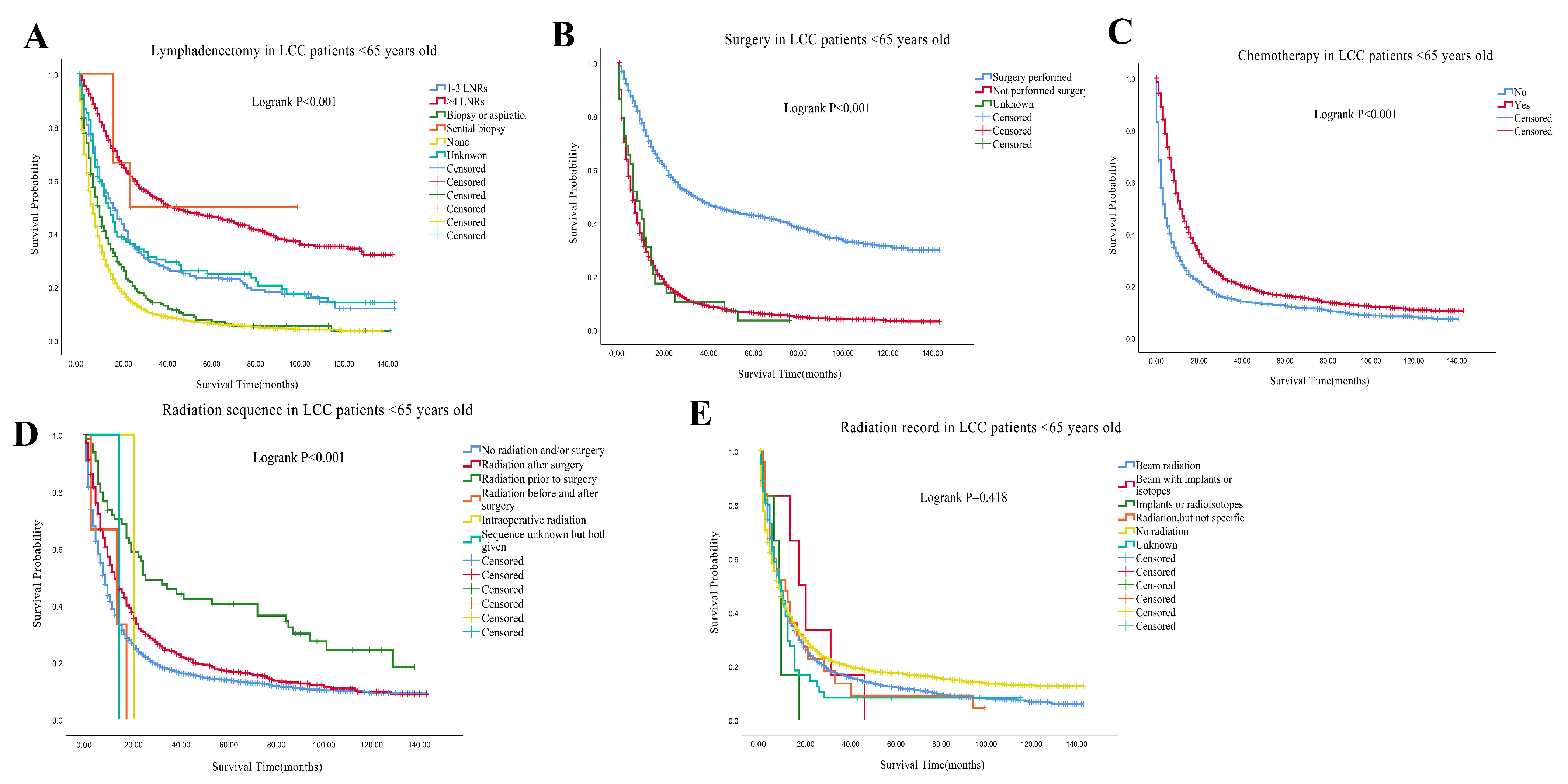

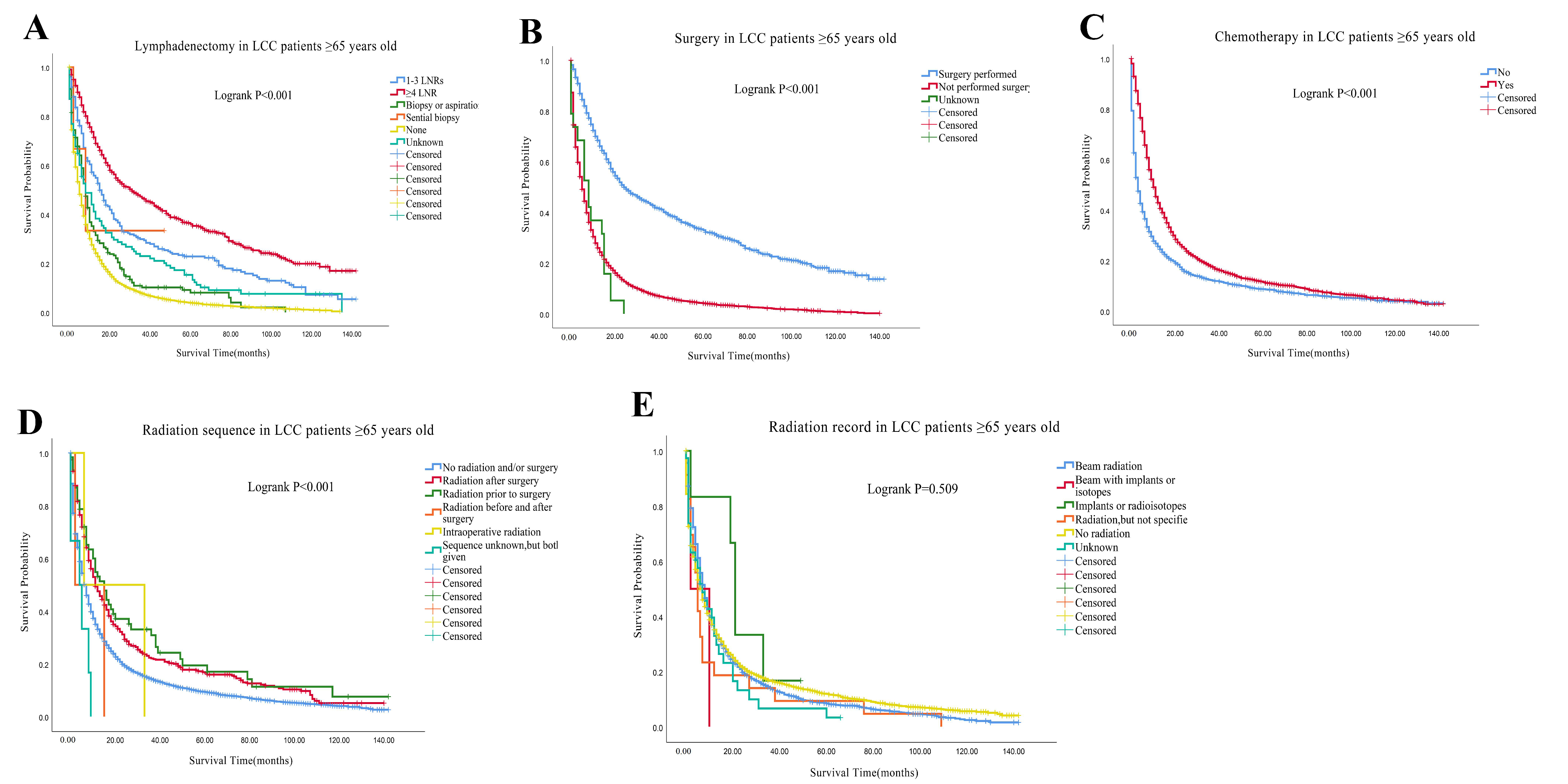

3.2. Survival Outcomes

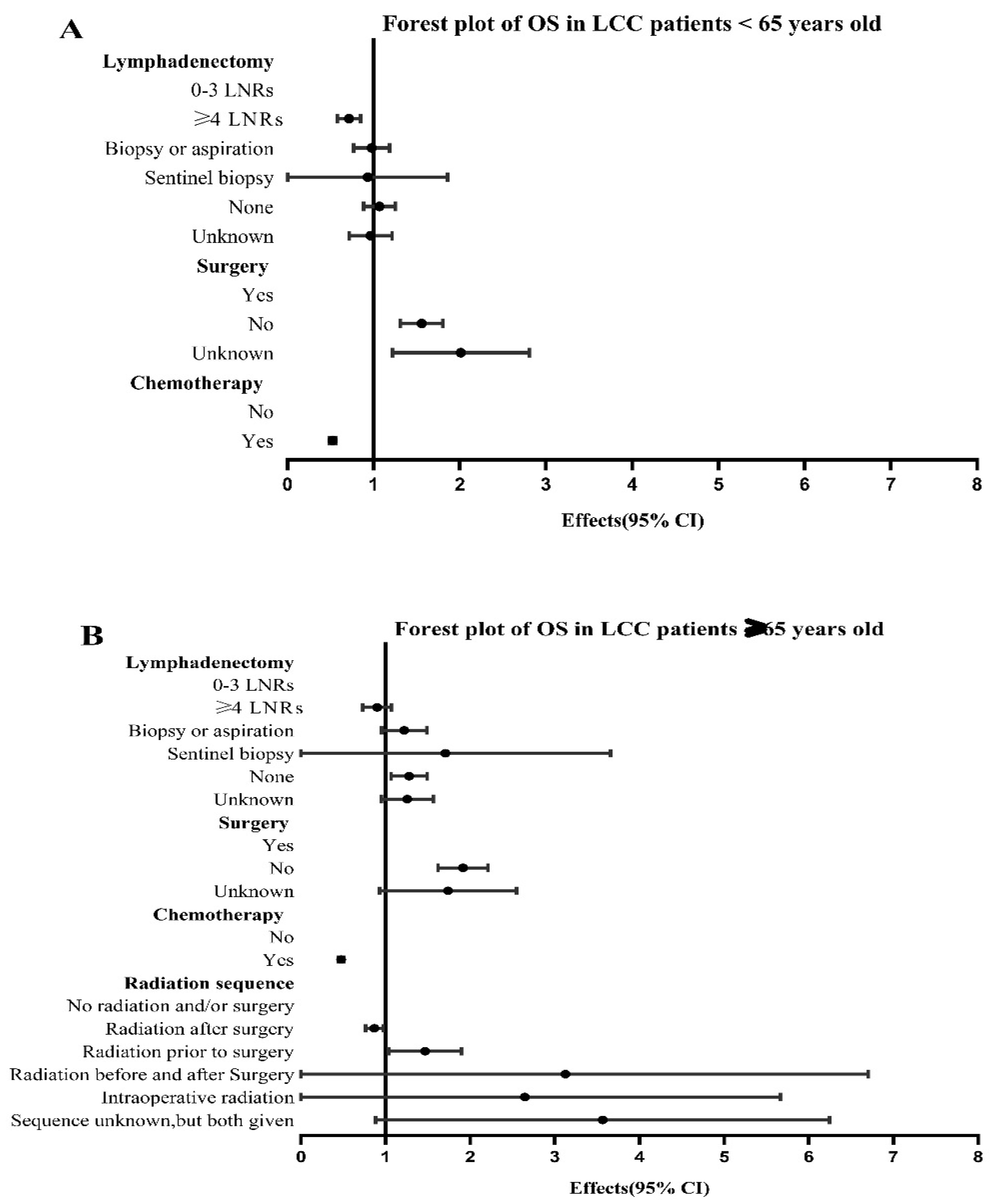

3.3. Univariate and Multivariate Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Fuchs, H.E.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholson, A.G.; Tsao, M.S.; Beasley, M.B.; Borczuk, A.C.; Brambilla, E.; Cooper, W.A.; Dacic, S.; Jain, D.; Kerr, K.M.; Lantuejoul, S.; et al. The 2021 WHO Classification of Lung Tumors: Impact of Advances Since 2015. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2021, 17, 362–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duma, N.; Santana-Davila, R.; Molina, J.R. Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Epidemiology, Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2019, 94, 1623–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rekhtman, N.; Travis, W.D. Large No More: The Journey of Pulmonary Large Cell Carcinoma from Common to Rare Entity. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2019, 14, 1125–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harms, A.; Endris, V.; Winter, H.; Kriegsmann, M.; Stenzinger, A.; Schirmacher, P.; Warth, A.; Kazdal, D. Molecular dissection of large cell carcinomas of the lung with null immunophenotype. Pathology 2018, 50, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donington, J.; Schumacher, L.; Yanagawa, J. Surgical Issues for Operable Early-Stage Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, K.A.; Puri, S.; Gray, J.E. Systemic and Radiation Therapy Approaches for Locally Advanced Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaft, J.E.; Shyr, Y.; Sepesi, B.; Forde, P.M. Preoperative and Postoperative Systemic Therapy for Operable Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 546–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.W.; Chau, S.L.; Tong, J.H.; Chow, C.; Kwan, J.S.; Chung, L.Y.; Lung, R.W.; Tong, C.Y.; Tin, E.K.; Law, P.P.; et al. The Landscape of Actionable Molecular Alterations in Immunomarker-Defined Large-Cell Carcinoma of the Lung. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2019, 14, 1213–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detterbeck, F.C.; Boffa, D.J.; Kim, A.W.; Tanoue, L.T. The Eighth Edition Lung Cancer Stage Classification. Chest 2017, 151, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Houtte, P.; Moretti, L.; Charlier, F.; Roelandts, M.; Van Gestel, D. Preoperative and postoperative radiotherapy (RT) for non-small cell lung cancer: Still an open question. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2021, 10, 1950–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ettinger, D.S.; Wood, D.E.; Aisner, D.L.; Akerley, W.; Bauman, J.R.; Bharat, A.; Bruno, D.S.; Chang, J.Y.; Chirieac, L.R.; D’Amico, T.A.; et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 2.2021. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2021, 19, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Expert Consensus on Adjuvant Therapy of Non-small Cell Lung Cancer from China Thoracic Surgeons (2018 Version). Chin. J. Lung Cancer 2018, 21, 731–737. [CrossRef]

- Tolwin, Y.; Gillis, R.; Peled, N. Gender and lung cancer—SEER-based analysis. Ann. Epidemiol. 2020, 46, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikh, M.; Mukeriya, A.; Shangina, O.; Brennan, P.; Zaridze, D. Postdiagnosis Smoking Cessation and Reduced Risk for Lung Cancer Progression and Mortality: A Prospective Cohort Study. Annals of internal medicine. Ann. Intern. Med. 2021, 174, 1232–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.-H.; Lin, S.-W.; Hsieh, C.-C.; Yeh, Y.-C.; Tu, C.-C.; Chen, K.-J. Treatment Outcomes of Patients With Different Subtypes of Large Cell Carcinoma of the Lung. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2014, 98, 1013–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, Y.; Qu, Y.; Liang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Liang, X.; Luo, Y.; Cao, J.; Zhang, H.; Feng, R. Clinicopathological analysis of Large Cell Lung Carcinomas definitely diagnosed according to the New World Health Organization Criteria. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2018, 214, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.C.; Jang, M.H.; Ahn, J.H. Metastatic large cell carcinoma of the lung: A rare cause of acute small bowel obstruction. Thorac. Cancer 2020, 11, 3379–3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Wei, C.; Zou, X.; Lu, B.; Wang, Z. Case Report: Long-Term Survival With Anlotinib in a Patient With Advanced Undifferentiated Large-Cell Lung Cancer and Rare Tonsillar Metastasis. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 680818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaochuan, L.; Jiangyong, Y.; Ping, Z.; Xiaonan, W.; Lin, L. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of pulmonary large cell carcinoma: A population-based retrospective study using SEER data. Thorac. Cancer 2020, 11, 1522–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zheng, H.; Chen, Q.; Bao, M.; Jiang, G.; Chen, C.; Gao, W. Triple Plasty of Bronchus, Pulmonary Artery, and Superior Vena Cava for Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2013, 95, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, W.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Q.; Liao, D.; Liu, Q.; Zhong, B.; Liang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, R.; Liu, G.; et al. Postoperative intensity-modulated radiation therapy reduces local recurrence and improves overall survival in III-N2 non-small-cell lung cancer: A single-center, retrospective study. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 2820–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Jiang, T.; Han, Y.; Zhu, A.; Xin, S.; Xue, M.; Xin, X.; Lu, Q. Effects of postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy on stage IIIA-N2 non-small cell lung cancer and prognostic analysis. Off. J. Balk. Union Oncol. 2021, 26, 328–335. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, W.-Y.; Ji, J.; Zuo, Y.-S.; Pu, J.; Xu, Y.-M.; Zong, C.-D.; Tao, G.-Z.; Chen, X.-F.; Ji, F.-Z.; Zhou, X.-L.; et al. Comparison of efficacy for postoperative chemotherapy and concurrent radiochemotherapy in patients with IIIA-pN2 non-small cell lung cancer: An early closed randomized controlled trial. Radiother. Oncol. 2013, 110, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Xie, H.; Chen, X.; Bi, N.; Qin, J.; Li, Y. Patient prognostic scores and association with survival improvement offered by postoperative radiotherapy for resected IIIA / N2 non-small cell lung cancer: A population-based study. Thorac. Cancer 2021, 12, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Pechoux, C.; Pourel, N.; Barlesi, F.; Lerouge, D.; Antoni, D.; Lamezec, B.; Nestle, U.; Boisselier, P.; Dansin, E.; Paumier, A.; et al. Postoperative radiotherapy versus no postoperative radiotherapy in patients with completely resected non-small-cell lung cancer and proven mediastinal N2 involvement (Lung ART, IFCT 0503): An open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 23, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAleese, J.; Baluch, S.; Drinkwater, K.; Bassett, P.; Hanna, G. The Elderly are Less Likely to Receive Recommended Radical Radiotherapy for Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 29, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driessen, E.J.; Schulkes, K.J.; Dingemans, A.-M.C.; van Loon, J.G.; Hamaker, M.E.; Aarts, M.J.; Janssen-Heijnen, M.L. Patterns of treatment and survival among older patients with stage III non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2018, 116, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, S.; Li, J.; Wu, N.; Yang, B.; Liu, S.; Ren, J.; Huang, Y.; et al. Trends of Postoperative Radiotherapy for Completely Resected Non-small Cell Lung Cancer in China: A Hospital-Based Multicenter 10–Year (2005–2014) Retrospective Clinical Epidemiological Study. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Xie, M.; Tian, J.; Song, X.; Wu, B.; Liu, L. Propensity score-matching analysis of postoperative radiotherapy for stage IIIA-N2 non-small cell lung cancer using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. Radiat. Oncol. 2017, 12, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Liang, L.; Xie, S.; Wang, C. The impact of order with radiation therapy in stage IIIA pathologic N2 NSCLC patients: A population-based study. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.-M.; Ku, H.-Y.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Wang, C.-L.; Chang, G.-C.; Chang, C.-S.; Liu, T.-W. Long-Term Survival Effect of the Interval between Postoperative Chemotherapy and Radiotherapy in Patients with Completely Resected Pathological N2 Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanagiri, T.; Oka, S.; Takenaka, S.; Baba, T.; Yasuda, M.; Ono, K.; So, T.; Uramoto, H.; Takenoyama, M.; Yasumoto, K. Results of surgical resection for patients with large cell carcinoma of the lung. Int. J. Surg. 2010, 8, 391–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Gulack, B.C.; Yang, C.-F.J.; Speicher, P.J.; Meza, J.M.; Gu, L.; Wang, X.; D’Amico, T.A.; Hartwig, M.G.; Berry, M.F. The impact of tumor size on the association of the extent of lymph node resection and survival in clinical stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2015, 90, 554–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziedzic, D.A.; Cackowski, M.M.; Zbytniewski, M.; Gryszko, G.M.; Woźnica, K.; Orłowski, T.M. The influence of the number of lymph nodes removed on the accuracy of a newly proposed N descriptor classification in patients with surgically-treated lung cancer. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 37, 101514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, X.; Dai, K.; Xu, B.; Liang, S.; Chen, M.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Z. The Prognostic Impact of Lymph Node Dissection on Primary Tumor Resection for Stage IV Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Population-Based Study. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 853257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Tai, Q.; Su, B.; Zhang, L. Adjuvant chemotherapy improves the prognosis of early stage resectable pulmonary large cell carcinoma: Analysis of SEER data. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2020, 9, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, Q.; Zhang, L.; Hu, X. Clinical characteristics and treatments of large cell lung carcinoma: A retrospective study using SEER data. Transl. Cancer Res. 2020, 9, 1455–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reck, M.; Remon, J.; Hellmann, M.D. First-Line Immunotherapy for Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.C.; Tan, D.S.W. Targeted Therapies for Lung Cancer Patients With Oncogenic Driver Molecular Alterations. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ruysscher, D.; van Baardwijk, A.; Wanders, R.; Hendriks, L.E.; Reymen, B.; van Empt, W.; Öllers, M.C.; Bootsma, G.; Pitz, C.; van Eijsden, L.; et al. Individualized accelerated isotoxic concurrent chemo-radiotherapy for stage III non-small cell lung cancer: 5-Year results of a prospective study. Radiother. Oncol. 2019, 135, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | LCC (n = 11,349) | Others (n = 129,118) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race | <0.001 | ||

| White | 9243(81.4%) | 106,372(82.4%) | |

| Black | 1568(13.8%) | 15,398(11.9%) | |

| Asian and others | 528(4.7%) | 7170(5.6%) | |

| Unknown | 10(0.1%) | 178(0.1%) | |

| Sex | <0.001 | ||

| Male | 6618(58.3%) | 78,075(60.5%) | |

| Female | 4731(41.7%) | 51,043(39.5%) | |

| Year of diagnosis | <0.001 | ||

| 2004–2007 | 5487(48.3%) | 39,869(30.9%) | |

| 2008–2011 | 3508(30.9%) | 43,981(34.1%) | |

| 2012–2015 | 2354(20.7%) | 45,268(35.1%) | |

| Region | <0.001 | ||

| East | 5979(52.7%) | 61,337(47.5%) | |

| Northern Plains | 1237(10.9%) | 14,743(11.4%) | |

| Southwest | 343(3.0%) | 3663(2.8%) | |

| Alaska and Pacific Coast | 3790(33.4%) | 49,375(38.2%) | |

| Tumor location | <0.001 | ||

| Upper lobe | 5857(51.6%) | 65,624(50.8%) | |

| Middle lobe | 465(4.1%) | 4843(3.8%) | |

| Lower lobe | 2573(22.7%) | 37,529(29.1%) | |

| NOS | 1761(15.5%) | 11,856(9.2%) | |

| Overlapping lesion | 137(1.2%) | 1817(1.4%) | |

| Main bronchus | 546(4.8%) | 7147(5.5%) | |

| Trachea | 10(0.1%) | 302(0.2%) | |

| Grade | <0.001 | ||

| Grade I | 28(0.2%) | 7401(5.7%) | |

| Grade II | 95(0.8%) | 33,817(26.2%) | |

| Grade III | 3368(29.7%) | 39,050(30.2%) | |

| Grade IV | 2781(24.5%) | 888(0.7%) | |

| Unknown | 5077(44.7%) | 47,961(37.1%) | |

| Stage | <0.001 | ||

| Stage I | 1269(11.2%) | 23,033(17.8%) | |

| Stage II | 668(5.9%) | 10,475(8.1%) | |

| Stage III | 2972(26.2%) | 40,502(31.4%) | |

| Stage IV | 5735(50.5%) | 45,210(35.0%) | |

| Unknown | 705(6.2%) | 9898(7.7%) | |

| Laterality | <0.001 | ||

| Right-origin of primary | 6282(55.4%) | 71,226(55.2%) | |

| Left—origin of primary | 4420(38.9%) | 53,577(41.5%) | |

| Bilateral, single primary | 172(1.5%) | 1401(1.1%) | |

| Paired, but no laterality | 401(3.5%) | 2184(1.7%) | |

| Others | 74(0.7%) | 730(0.6%) | |

| Lymphadenectomy | <0.001 | ||

| 0–3 LNRs | 585(5.2%) | 5949(4.6%) | |

| ≥4 LNRs | 1683(14.8%) | 25,491(19.7%) | |

| Biopsy or aspiration | 542(4.8%) | 5829(4.5%) | |

| Sentinel biopsy | 14(0.1%) | 246(0.2%) | |

| None | 8216(72.4%) | 88,610(68.6%) | |

| Unknown | 309(2.7%) | 2993(2.3%) | |

| Surgery record | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 2419(21.3%) | 35,272(27.3%) | |

| No | 8854(78.0%) | 124,529(71.9%) | |

| Unknown | 76(0.7%) | 1062(0.8%) | |

| Radiation sequence | <0.001 | ||

| No radiation and/or surgery | 9951(87.7%) | 115,975(89.8%) | |

| Radiation after surgery | 1218(10.7%) | 11,180(8.7%) | |

| Radiation prior to surgery | 156(1.4%) | 1611(1.2%) | |

| Radiation before and after surgery | 12(0.1%) | 197(0.2%) | |

| Intraoperative radiation | 3(0.0%) | 27(0.0%) | |

| Sequence unknown, but both given | 14(0.1%) | 88(0.1%) | |

| Surgery before and after radiation | 0(0.0%) | 28(0.0%) | |

| Radiation in and before/after surgery | 0(0.0%) | 12(0.0%) | |

| Radiation record | 0.002 | ||

| Beam radiation | 4680(41.2%) | 52,573(40.7%) | |

| Beam with implants or isotopes | 8(0.1%) | 204(0.2%) | |

| Implant or radioisotopes | 18(0.2%) | 269(0.2%) | |

| Radiation, but not specified | 58(0.5%) | 777(0.6%) | |

| No radiation | 6445(56.8%) | 74,095(57.4%) | |

| Unknown | 140(1.2%) | 1200(0.9%) | |

| Chemotherapy record | 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 5408(47.7%) | 57,335(44.4%) | |

| No/unknown | 5941(52.3%) | 71,783(55.6%) | |

| Tumor Size | <0.001 | ||

| ≤1 cm | 8567(75.5%) | 102,975(79.8%) | |

| >1, ≤2 cm | 7(0.1%) | 57(0.0%) | |

| >2, ≤3 cm | 9(0.1%) | 102(0.1%) | |

| >3, ≤4 cm | 9(0.1%) | 100(0.1%) | |

| >4 cm | 6(0.1%) | 62(0.0%) | |

| Unknown | 2751(24.2%) | 25,822(20.0%) | |

| Bone Metastasis | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 759(6.7%) | 8056(6.2%) | |

| No | 2937(25.9%) | 57,178(44.3%) | |

| Unknown | 7653(67.4%) | 63,884(49.5%) | |

| Brain Metastasis | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 668(5.9%) | 4139(3.2%) | |

| No | 3024(26.6%) | 61,029(47.3%) | |

| Unknown | 7657(67.5%) | 63,950(49.5%) | |

| Liver Metastasis | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 610(5.4%) | 4099(3.2%) | |

| No | 3086(27.2%) | 61,089(47.3%) | |

| Unknown | 7653(67.4%) | 63,930(49.5%) | |

| Lung Metastasis | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 551(4.9%) | 8226(6.4%) | |

| No | 3125(27.5%) | 56,758(44.0%) | |

| Unknown | 7673(67.6%) | 64,134(49.7%) | |

| First malignant primary indicator | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 9213(81.2%) | 98,320(76.1%) | |

| No | 2136(18.8%) | 30,798(23.9%) | |

| Age at diagnosis | <0.001 | ||

| <65 | 4300(37.9%) | 37,481(29.0%) | |

| ≥65 | 7049(62.1%) | 91,636(71.0%) | |

| Insurance status | <0.001 | ||

| Any Medicaid | 993(8.7%) | 13,440(10.4%) | |

| Insured or no specifics | 5655(49.8%) | 81,576(63.2%) | |

| Uninsured | 260(2.3%) | 2372(1.8%) | |

| Unknown | 4441(39.1%) | 31,730(24.6%) | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | ||

| Married or domestic partner | 5975(52.6%) | 66,147(51.2%) | |

| Divorced/separated/single/widowed | 4995(44.0%) | 57,548(44.6%) | |

| Unknown | 379(3.3%) | 5423(4.2%) | |

| High School education (%) | <0.001 | ||

| ≤10 | 2050(18.1%) | 26,234(20.3%) | |

| >10, ≤20 | 5984(52.7%) | 66,441(51.5%) | |

| >20, ≤30 | 2981(26.3%) | 32,302(25.0%) | |

| >30 | 332(2.9%) | 4128(3.2%) | |

| Unknown | 2(0.0%) | 13(0.0%) | |

| Median Family income (dollar, in tens) | <0.001 | ||

| ≤5000 | 1682(14.8%) | 16,744(13.0%) | |

| >5000, ≤7000 | 5745(50.6%) | 62,365(48.3%) | |

| >7000, ≤9000 | 2854(25.1%) | 34,034(26.4%) | |

| >9000 | 1066(9.4%) | 15,962(12.4%) | |

| Unknown | 2(0.0%) | 13(0.0%) |

| Median Survival Months | 1-Year of OS (%) | 3-Year of OS (%) | 5-Year of OS (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other types of NSCLC | 10 | 44.1 | 21.1 | 14.9 |

| LCC | 7 | 34.5 | 15.7 | 11.2 |

| LCC < 65 years old | 8 | 38.9 | 18.6 | 14.5 |

| Bone metastasis | 3 | 14.4 | 3.5 | 1.2 |

| Brain metastasis | 5 | 20.0 | 6.5 | 3.5 |

| Liver metastasis | 3 | 11.2 | 1.5 | 0.0 |

| Lung metastasis | 4 | 18.0 | 3.4 | 0.0 |

| LCC ≥ 65 years old | 7 | 35.1 | 15.3 | 10.3 |

| Bone metastasis | 3 | 11.3 | 0.8 | 0.0 |

| Brain metastasis | 4 | 13.8 | 2.0 | 0.0 |

| Liver metastasis | 3 | 13.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Lung metastasis | 4 | 18.4 | 3.4 | 2.6 |

| Variables | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | |

| Race | 0.049 | <0.001 | ||

| White | Reference | Reference | ||

| Black | 1.072(1.005–1.144) | 0.035 | 0.957(0.895–1.024) | 0.203 |

| Asian and others | 0.913(0.819–1.019) | 0.105 | 0.785(0.701–0.878) | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 0.935(0.389–2.247) | 0.880 | 1.177(0.489–2.836) | 0.716 |

| Sex | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Male | Reference | Reference | ||

| Female | 0.862(0.822–0.904) | <0.001 | 0.845(0.804–0.888) | <0.001 |

| Year of diagnosis | 0.760 | |||

| 2004–2007 | Reference | |||

| 2008–2011 | 0.980(0.929–1.034) | 0.459 | ||

| 2012–2015 | 0.992(0.929–1.060) | 0.808 | ||

| Region | 0.706 | |||

| East | Reference | |||

| Northern Plains | 1.036(0.959–1.119) | 0.367 | ||

| Southwest | 1.005(0.872–1.158) | 0.946 | ||

| Alaska and Pacific Coast | 0.986(0.935–1.040) | 0.605 | ||

| Tumor location | <0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| Upper lobe | Reference | Reference | ||

| Middle lobe | 1.113(0.989–1.251) | 0.075 | 1.085(0.962–1.223) | 0.186 |

| Lower lobe | 1.105(1.041–1.173) | 0.001 | 1.083(1.019–1.151) | 0.010 |

| NOS | 1.696(1.586–1.813) | <0.001 | 1.160(1.068–1.260) | <0.001 |

| Overlapping lesion | 1.717(0.942–1.455) | 0.156 | 1.157(0.929–1.440) | 0.193 |

| Main bronchus | 1.464(1.314–1.631) | <0.001 | 1.184(1.061–1.322) | 0.003 |

| Trachea | 1.161(0.521–2.587) | 0.714 | 1.779(0.749–4.277) | 0.192 |

| Grade | <0.001 | 0.049 | ||

| Grade I | Reference | Reference | ||

| Grade II | 0.898(0.492–1.640) | 0.726 | 1.011(0.549–1.861) | 0.972 |

| Grade III | 1.122(0.650–1.936) | 0.679 | 1.282(0.737–2.229) | 0.379 |

| Grade IV | 1.190(0.689–2.054) | 0.533 | 1.362(0.783–2.370) | 0.274 |

| Unknown | 1.548(0.898–2.669) | 0.166 | 1.272(0.732–2.211) | 0.394 |

| Stage | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Stage I | Reference | Reference | ||

| Stage II | 1.386(1.204–1.597) | <0.001 | 1.633(1.415–1.884) | <0.001 |

| Stage III | 2.497(2.257–2.764) | <0.001 | 2.088(1.791–2.251) | <0.001 |

| Stage IV | 4.764(4.321–5.252) | <0.001 | 3.115(2.775–3.496) | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 3.169(2.780–3.612) | <0.001 | 1.555(1.342–1.803) | <0.001 |

| Laterality | <0.001 | 0.004 | ||

| Right-origin of primary | Reference | Reference | ||

| Left-origin of primary | 1.018(0.970–1.070) | 0.468 | 1.033(0.982–1.087) | 0.206 |

| Bilateral, single primary | 1.906(1.593–2.280) | <0.001 | 0.949(0.783–1.150) | 0.592 |

| Paired, but no laterality | 1.434(1.261–1.630) | <0.001 | 0.781(0.675–0.904) | 0.001 |

| Others | 1.483(1.131–1.945) | 0.004 | 0.798(0.593–1.075) | 0.138 |

| Lymphadenectomy | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| 0–3 LNRs | Reference | Reference | ||

| ≥4 LNRs | 0.579(0.511–0.655) | <0.001 | 0.790(0.692–0.903) | 0.001 |

| Biopsy or aspiration | 1.597(1.384–1.844) | <0.001 | 1.079(0.926–1.257) | 0.333 |

| Sentinel biopsy | 0.556(0.230–1.343) | 0.192 | 0.779(0.321–1.890) | 0.581 |

| None | 2.013(1.811–2.239) | <0.001 | 1.162(1.031–1.309) | 0.014 |

| Unknown | 1.140(0.957–1.359) | 0.142 | 1.077(0.902–1.287) | 0.411 |

| Surgery record | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | ||

| No | 3.107(2.912–3.316) | <0.001 | 1.714(1.535–1.914) | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 3.142(2.346–4.208) | <0.001 | 1.798(1.323–2.444) | <0.001 |

| Radiation sequence | <0.001 | 0.009 | ||

| No radiation and/or surgery | Reference | Reference | ||

| Radiation after surgery | 0.747(0.695–0.802) | <0.001 | 0.913(0.840–0.992) | 0.032 |

| Radiation prior to surgery | 0.542(0.442–0.665) | <0.001 | 1.128(0.911–1.396) | 0.269 |

| Radiation before and after surgery | 1.232(0.512–2.960) | 0.641 | 1.778(0.736–4.298) | 0.201 |

| Intraoperative radiation | 0.802(0.259–2.487) | 0.702 | 1.040(0.334–3.236) | 0.946 |

| Sequence unknown, but both given | 1.811(0.863–3.801) | 0.116 | 2.711(1.284–5.724) | 0.009 |

| Radiation record | 0.766 | |||

| Beam radiation | Reference | |||

| Beam with implants or isotopes | 0.955(0.477–1.911) | 0.896 | ||

| Implant or radioisotopes | 0.905(0.501–1.635) | 0.740 | ||

| Radiation, but not specified | 1.127(0.840–1.512) | 0.426 | ||

| No radiation | 0.987(0.941–1.035) | 0.593 | ||

| Unknown | 1.135(0.914–1.410) | 0.251 | ||

| Chemotherapy record | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| No/unknown | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.639(0.610–0.670) | <0.001 | 0.501(0.477–0.528) | <0.001 |

| Tumor Size | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| ≤1 cm | Reference | Reference | ||

| >1, ≤2 cm | 1.530(0.493–4.747) | 0.461 | 1.678(0.539–5.230) | 0.372 |

| >2, ≤3 cm | 0.935(0.389–2.249) | 0.881 | 0.595(0.247–1.437) | 0.249 |

| >3, ≤4 cm | 1.378(0.689–2.757) | 0.365 | 1.334(0.663–2.682) | 0.419 |

| >4 cm | 1.306(0.490–3.483) | 0.593 | 0.637(0.238–1.703) | 0.369 |

| Unknown | 1.690(1.602–1.783) | <0.001 | 1.195(1.122–1.273) | <0.001 |

| Bone Metastasis | <0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 2.193(1.981–2.426) | <0.001 | 1.227(1.101–1.368) | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 1.184(1.118–1.254) | <0.001 | 1.305(0.908–1.877) | 0.151 |

| Brain Metastasis | <0.001 | 0.097 | ||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.777(1.601–1.974) | <0.001 | 1.110(0.995–1.239) | 0.062 |

| Unknown | 1.139(1.076–1.206) | <0.001 | 0.872(0.631–1.205) | 0.407 |

| Liver Metastasis | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 2.375(2.124–2.656) | <0.001 | 1.442(1.279–1.624) | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 1.149(1.086–1.215) | <0.001 | 1.082(0.737–1.588) | 0.688 |

| Lung Metastasis | <0.001 | 0.220 | ||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.880(1.673–2.113) | <0.001 | 1.095(0.969–1.237) | 0.147 |

| Unknown | 1.117(1.056–1.181) | <0.001 | 0.887(0.657–1.198) | 0.435 |

| First malignant primary indicator | 0.001 | 0.591 | ||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.132(1.053–1.217) | 0.001 | 1.020(0.948–1.098) | 0.591 |

| Age at diagnosis | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| <65 | Reference | Reference | ||

| ≥65 | 1.156(1.103–1.211) | <0.001 | 1.230(1.171–1.291) | <0.001 |

| Insurance status | <0.001 | 0.003 | ||

| Any Medicaid | Reference | Reference | ||

| Insured or no specifics | 0.817(0.752–0.888) | <0.001 | 0.881(0.808–0.961) | 0.004 |

| Uninsured | 1.063(0.910–1.242) | 0.441 | 1.083(0.925–1.268) | 0.321 |

| Unknown | 0.875(0.805–0.952) | 0.002 | 0.914(0.833–1.002) | 0.056 |

| Marital status | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Married or domestic partner | Reference | Reference | ||

| Divorced/separated/single/widowed | 1.187(1.132–1.245) | <0.001 | 1.121(1.065–1.179) | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 1.113(0.974–1.272) | 0.114 | 1.087(0.949–1.245) | 0.230 |

| High School education (%) | <0.001 | 0.681 | ||

| ≤10 | Reference | Reference | ||

| >10, ≤20 | 1.065(0.998–1.137) | 0.058 | 1.017(0.946–1.094) | 0.647 |

| >20, ≤30 | 1.200(1.116–1.290) | <0.001 | 1.063(0.970–1.165) | 0.190 |

| >30 | 1.195(1.035–1.381) | 0.015 | 1.065(0.900–1.260) | 0.463 |

| Unknown | 0.955(0.134–6.786) | 0.963 | 1.021(0.143–7.305) | 0.984 |

| Median family income (dollar, in tens) | <0.001 | 0.196 | ||

| ≤5000 | Reference | Reference | ||

| >5000, ≤7000 | 1.019(0.954–1.089) | 0.575 | 1.065(0.987–1.148) | 0.104 |

| >7000, ≤9000 | 0.877(0.814–0.946) | 0.001 | 1.060(0.964–1.165) | 0.232 |

| >9000 | 0.812(0.735–0.898) | <0.001 | 0.990(0.877–1.118) | 0.872 |

| Unknown | 0.840(0.118–5.972) | 0.862 | ||

| Variables | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | |

| Race | 0.146 | |||

| White | Reference | |||

| Black | 1.098(1.007–1.197) | 0.034 | ||

| Asian and others | 0.964(0.812–1.144) | 0.672 | ||

| Unknown | 0.501(0.071–3.599) | 0.490 | ||

| Sex | <0.001 | 0.003 | ||

| Male | Reference | Reference | ||

| Female | 0.824(0.769–0.882) | <0.001 | 0.898(0.837–0.963) | 0.003 |

| Year of diagnosis | 0.586 | |||

| 2004–2007 | Reference | |||

| 2008–2011 | 0.983(0.911–1.062) | 0.667 | ||

| 2012–2015 | 1.037(0.944–1.139) | 0.448 | ||

| Region | 0.976 | |||

| East | Reference | |||

| Northern Plains | 0.995(0.891–1.112) | 0.933 | ||

| Southwest | 0.970(0.791–1.189) | 0.767 | ||

| Alaska and Pacific Coast | 1.011(0.937–1.090) | 0.782 | ||

| Tumor location | <0.001 | 0.012 | ||

| Upper lobe | Reference | Reference | ||

| Middle lobe | 1.200(1.013–1.421) | 0.035 | 1.210(1.018–1.440) | 0.031 |

| Lower lobe | 1.196(1.092–1.309) | <0.001 | 1.117(1.019–1.225) | 0.018 |

| NOS | 1.754(1.596–1.929) | <0.001 | 1.129(0.999–1.276) | 0.051 |

| Overlapping lesion | 0.968(0.705–1.330) | 0.842 | 0.908(0.659–1.251) | 0.554 |

| Main bronchus | 1.540(1.332–1.781) | <0.001 | 1.232(1.062–1.429) | 0.006 |

| Trachea | 1.740(0.435–6.965) | 0.434 | 1.574(0.358–6.911) | 0.548 |

| Grade | <0.001 | 0.411 | ||

| Grade I | Reference | Reference | ||

| Grade II | 0.733(0.365–1.473) | 0.384 | 0.777(0.381–1.586) | 0.489 |

| Grade III | 0.858(0.473–1.554) | 0.612 | 1.024(0.556–1.885) | 0.941 |

| Grade IV | 0.940(0.518–1.703) | 0.837 | 1.083(0.588–1.994) | 0.799 |

| Unknown | 1.218(0.673–2.204) | 0.515 | 1.031(0.560–1.896) | 0.922 |

| Stage | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Stage I | Reference | Reference | ||

| Stage II | 1.467(1.187–1.812) | <0.001 | 1.803(1.455–2.234) | <0.001 |

| Stage III | 2.857(2.446–3.336) | <0.001 | 2.288(1.915–2.734) | <0.001 |

| Stage IV | 5.556(4.786–6.450) | <0.001 | 3.630(3.032–4.346) | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 3.584(2.892–4.442) | <0.001 | 1.836(1.443–2.337) | <0.001 |

| Laterality | <0.001 | 0.055 | ||

| Right-origin of primary | Reference | Reference | ||

| Left—origin of primary | 1.046(0.974–1.122) | 0.218 | 1.094(1.017–1.177) | 0.016 |

| Bilateral, single primary | 1.963(1.524–2.530) | <0.001 | 1.117(0.849–1.471) | 0.428 |

| Paired, but no laterality | 1.493(1.256–1.776) | <0.001 | 0.875(0.716–1.070) | 0.193 |

| Others | 1.747(1.186–2.574) | 0.005 | 0.997(0.657–1.511) | 0.988 |

| Lymphadenectomy | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| 0–3 LNRs | Reference | Reference | ||

| ≥4 LNRs | 0.523(0.437–0.625) | <0.001 | 0.707(0.584–0.855) | <0.001 |

| Biopsy or aspiration | 1.558(1.274–1.905) | <0.001 | 0.964(0.778–1.194) | 0.738 |

| Sentinel biopsy | 0.429(0.137–1.343) | 0.146 | 0.625(0.198–1.971) | 0.423 |

| None | 1.918(1.647–2.233) | <0.001 | 1.057(0.890–1.255) | 0.527 |

| Unknown | 0.987(0.766–1.272) | 0.919 | 0.945(0.729–1.225) | 0.670 |

| Surgery record | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | ||

| No | 3.267(2.974–3.588) | <0.001 | 1.544(1.317–1.811) | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 3.232(2.209–4.729) | <0.001 | 1.907(1.274–2.854) | 0.002 |

| Radiation sequence | <0.001 | 0.580 | ||

| No radiation and/or surgery | Reference | Reference | ||

| Radiation after surgery | 0.791(0.716–0.873) | <0.001 | 0.944(0.840–1.062) | 0.339 |

| Radiation prior to surgery | 0.481(0.358–0.646) | <0.001 | 0.929(0.680–1.270) | 0.646 |

| Radiation before and after surgery | 1.213(0.391–3.765) | 0.738 | 1.738(0.557–5.425) | 0.341 |

| Intraoperative radiation | 0.765(0.108–5.436) | 0.789 | 0.584(0.082–4.174) | 0.592 |

| Sequence unknown, but both given | 0.956(0.135–6.793) | 0.964 | 3.344(0.466–24.006) | 0.230 |

| Radiation record | 0.462 | |||

| Beam radiation | Reference | |||

| Beam with implants or isotopes | 0.854(0.383–1.903) | 0.699 | ||

| Implant or radioisotopes | 1.455(0.652–3.243) | 0.360 | ||

| Radiation, but not specified | 1.008(0.668–1.521) | 0.970 | ||

| No radiation | 0.947(0.885–1.014) | 0.120 | ||

| Unknown | 1.131(0.856–1.495) | 0.385 | ||

| Chemotherapy record | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| No/unknown | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.639(0.597–0.684) | <0.001 | 0.524(0.487–0.563) | <0.001 |

| Tumor Size | <0.001 | 0.011 | ||

| ≤1 cm | Reference | Reference | ||

| >1, ≤2 cm | 1.122(0.280–4.490) | 0.871 | 1.183(0.292–4.783) | 0.814 |

| >2, ≤3 cm | 6.627(0.932–47.124) | 0.059 | 2.749(0.383–19.751) | 0.315 |

| >3, ≤4 cm | 1.215(0.505–2.921) | 0.664 | 1.321(0.546–3.197) | 0.537 |

| Unknown | 1.705(1.579–1.841) | <0.001 | 1.172(1.071–1.284) | 0.001 |

| Bone Metastasis | <0.001 | 0.060 | ||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 2.247(1.955–2.584) | <0.001 | 1.189(1.023–1.382) | 0.024 |

| Unknown | 1.152(1.060–1.251) | 0.001 | 1.358(0.795–2.322) | 0.263 |

| Brain Metastasis | <0.001 | 0.759 | ||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.716(1.489–1.977) | <0.001 | 1.039(0.894–1.209) | 0.616 |

| Unknown | 1.095(1.009–1.189) | 0.030 | 0.883(0.522–1.495) | 0.644 |

| Liver Metastasis | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 2.579(2.217–3.001) | <0.001 | 1.582(1.342–1.866) | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 1.120(1.034–1.214) | 0.006 | 0.919(0.520–1.623) | 0.771 |

| Lung Metastasis | <0.001 | 0.579 | ||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 2.041(1.743–2.389) | <0.001 | 1.091(0.923–1.290) | 0.309 |

| Unknown | 1.085(1.002–1.175) | 0.044 | 0.965(0.589–1.581) | 0.889 |

| First malignant primary indicator | <0.001 | 0.085 | ||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.214(1.091–1.351) | <0.001 | 1.100(0.987–1.227) | 0.085 |

| Insurance status | <0.001 | 0.002 | ||

| Any Medicaid | Reference | Reference | ||

| Insured or no specifics | 0.746(0.671–0.829) | <0.001 | 0.851(0.762–0.950) | 0.004 |

| Uninsured | 1.079(0.913–1.276) | 0.372 | 1.072(0.904–1.272) | 0.421 |

| Unknown | 0.821(0.739–0.912) | <0.001 | 0.930(0.826–1.047) | 0.231 |

| Marital status | <0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| Married or domestic partner | Reference | Reference | ||

| Divorced/separated/single/widowed | 1.219(1.139–1.305) | <0.001 | 1.143(1.064–1.229) | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 1.132(0.924–1.386) | 0.230 | 1.040(0.844–1.282) | 0.711 |

| High School education (%) | <0.001 | 0.609 | ||

| ≤10 | Reference | Reference | ||

| >10, ≤20 | 1.085(0.988–1.192) | 0.089 | 1.014(0.914–1.126) | 0.790 |

| >20, ≤30 | 1.270(1.144–1.410) | <0.001 | 1.079(0.947–1.230) | 0.251 |

| >30 | 1.301(1.060–1.597) | 0.012 | 1.154(0.908–1.466) | 0.241 |

| Unknown | 1.024(1.144–7.286) | 0.981 | 1.036(0.143–7.487) | 0.972 |

| Median family income (dollar, in tens) | <0.001 | 0.520 | ||

| ≤5000 | Reference | Reference | ||

| >5000, ≤7000 | 1.014(0.922–1.115) | 0.773 | 1.051(0.944–1.171) | 0.364 |

| >7000, ≤9000 | 0.843(0.757–0.939) | 0.002 | 1.015(0.888–1.159) | 0.831 |

| >9000 | 0.748(0.647–0.865) | <0.001 | 0.959(0.806–1.141) | 0.636 |

| Unknown | 0.861(0.121–6.124) | 0.881 | ||

| Variables | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | |

| Race | 0.044 | 0.003 | ||

| White | Reference | Reference | ||

| Black | 1.079(0.978–1.191) | 0.128 | 0.948(0.856–1.050) | 0.307 |

| Asian and others | 0.850(0.738–0.980) | 0.025 | 0.765(0.661–0.885) | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 1.173(0.440–3.128) | 0.750 | 1.121(0.419–3.002) | 0.820 |

| Sex | 0.002 | <0.001 | ||

| Male | Reference | Reference | ||

| Female | 0.899(0.842–0.961) | 0.002 | 0.800(0.745–0.859) | <0.001 |

| Year of diagnosis | 0.535 | |||

| 2004–2007 | Reference | |||

| 2008–2011 | 0.977(0.907–1.052) | 0.540 | ||

| 2012–2015 | 0.950(0.866–1.043) | 0.280 | ||

| Region | 0.180 | |||

| East | Reference | |||

| Northern Plains | 1.082(0.973–1.204) | 0.147 | ||

| Southwest | 1.049(0.861–1.278) | 0.633 | ||

| Alaska and Pacific Coast | 0.957(0.889–1.030) | 0.238 | ||

| Tumor location | <0.001 | 0.003 | ||

| Upper lobe | Reference | Reference | ||

| Middle lobe | 1.018(0.865–1.199) | 0.826 | 0.970(0.820–1.148) | 0.723 |

| Lower lobe | 1.000(0.923–1.084) | 0.994 | 1.056(0.973–1.146) | 0.189 |

| NOS | 1.618(1.472–1.778) | <0.001 | 1.189(1.061–1.332) | 0.003 |

| Overlapping lesion | 1.533(1.136–2.067) | 0.005 | 1.585(1.173–2.142) | 0.003 |

| Main bronchus | 1.396(1.186–1.643) | <0.001 | 1.104(0.935–1.303) | 0.243 |

| Trachea | 0.908(0.340–2.423) | 0.848 | 2.204(0.744–6.529) | 0.154 |

| Grade | <0.001 | 0.136 | ||

| Grade I | Reference | Reference | ||

| Grade II | 1.884(0.449–7.908) | 0.387 | 1.719(0.406–7.278) | 0.462 |

| Grade III | 2.520(0.628–10.104) | 0.192 | 2.092(0.517–8.464) | 0.301 |

| Grade IV | 2.572(0.641–10.314) | 0.183 | 2.256(0.557–9.135) | 0.254 |

| Unknown | 3.376(0.842–13.532) | 0.186 | 2.053(0.508–8.304) | 0.313 |

| Stage | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Stage I | Reference | Reference | ||

| Stage II | 1.367(1.129–1.655) | 0.001 | 1.503(1.239–1.824) | <0.001 |

| Stage III | 2.243(1.961–2.565) | <0.001 | 1.863(1.604–2.164) | <0.001 |

| Stage IV | 4.262(3.743–4.852) | <0.001 | 2.866(2.462–3.336) | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 2.762(2.339–3.261) | <0.001 | 1.394(1.155–1.682) | 0.001 |

| Laterality | <0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| Right-origin of primary | Reference | Reference | ||

| Left-origin of primary | 0.981(0.917–1.050) | 0.584 | 0.970(0.904–1.040) | 0.393 |

| Bilateral, single primary | 1.840(1.428–2.369) | <0.001 | 0.810(0.618–1.061) | 0.126 |

| Paired, but no laterality | 1.376(1.136–1.668) | 0.001 | 0.669(0.539–0.830) | <0.001 |

| Others | 1.237(0.846–1.808) | 0.272 | 0.569(0.369–0.877) | 0.011 |

| Lymphadenectomy | <0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| 0–3 LNRs | Reference | Reference | ||

| ≥4 LNRs | 0.655(0.552–0.779) | <0.001 | 0.890(0.738–1.073) | 0.222 |

| Biopsy or aspiration | 1.686(1.373–2.072) | <0.001 | 1.201(0.962–1.499) | 0.106 |

| Sentinel biopsy | 1.036(0.257–4.173) | 0.960 | 0.965(0.238–3.921) | 0.961 |

| None | 2.162(1.864–2.507) | <0.001 | 1.267(1.071–1.498) | 0.006 |

| Unknown | 1.366(1.070–1.742) | 0.012 | 1.231(0.962–1.575) | 0.099 |

| Surgery record | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | ||

| No | 2.977(2.720–3.258) | <0.001 | 1.900(1.628–2.217) | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 3.244(2.052–5.128) | <0.001 | 1.612(0.998–2.604) | 0.051 |

| Radiation sequence | <0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| No radiation and/or surgery | Reference | Reference | ||

| Radiation after surgery | 0.706(0.636–0.784) | <0.001 | 0.863(0.765–0.973) | 0.016 |

| Radiation prior to surgery | 0.635(0.479–0.842) | 0.002 | 1.425(1.059–1.916) | 0.019 |

| Radiation before and after surgery | 1.306(0.326–5.225) | 0.706 | 1.759(0.431–7.183) | 0.431 |

| Intraoperative radiation | 0.803(0.201–3.213) | 0.757 | 1.498(0.370–6.068) | 0.571 |

| Sequence unknown, but both given | 2.039(0.915–4.545) | 0.081 | 2.892(1.283–6.520) | 0.010 |

| Radiation record | 0.560 | |||

| Beam radiation | Reference | |||

| Beam with implants or isotopes | 1.677(0.419–6.712) | 0.465 | ||

| Implant or radioisotopes | 0.612(0.254–1.472) | 0.273 | ||

| Radiation, but not specified | 1.280(0.840–1.950) | 0.250 | ||

| No radiation | 1.017(0.952–1.087) | 0.621 | ||

| Unknown | 1.166(0.826–1.646) | 0.383 | ||

| Chemotherapy record | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| No/unknown | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.645(0.604–0.689) | <0.001 | 0.474(0.441–0.509) | <0.001 |

| Tumor Size | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| ≤1 cm | Reference | Reference | ||

| >1, ≤2 cm | 11.188(1.572–79.621) | 0.016 | 4.162(0.583–29.731) | 0.155 |

| >2, ≤3 cm | 0.719(0.269–1.916) | 0.509 | 0.480(0.179–1.287) | 0.145 |

| >3, ≤4 cm | 2.107(0.679–6.540) | 0.197 | 1.147(0.357–3.690) | 0.818 |

| >4 cm | 1.236(0.464–3.297) | 0.672 | 0.631(0.236–1.691) | 0.360 |

| Unknown | 1.674(1.554–1.804) | <0.001 | 1.224(1.120–1.337) | <0.001 |

| Bone Metastasis | <0.001 | 0.015 | ||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 2.160(1.863–2.503) | <0.001 | 1.269(1.081–1.489) | 0.004 |

| Unknown | 1.217(1.123–1.319) | <0.001 | 1.199(0.729–1.973) | 0.475 |

| Brain Metastasis | <0.001 | 0.070 | ||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.903(1.627–2.225) | <0.001 | 1.193(1.013–1.406) | 0.035 |

| Unknown | 1.186(1.096–1.284) | <0.001 | 0.874(0.576–1.324) | 0.524 |

| Liver Metastasis | <0.001 | 0.010 | ||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 2.186(1.852–2.581) | <0.001 | 1.315(1.101–1.572) | 0.003 |

| Unknown | 1.178(1.089–1.274) | <0.001 | 1.225(0.718–2.090) | 0.457 |

| Lung Metastasis | <0.001 | 0.506 | ||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.721(1.446–2.049) | <0.001 | 1.076(0.895–1.293) | 0.436 |

| Unknown | 1.149(1.063–1.242) | <0.001 | 0.865(0.589–1.270) | 0.459 |

| First malignant primary indicator | 0.239 | |||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 1.061(0.961–1.171) | 0.239 | ||

| Insurance status | 0.063 | |||

| Any Medicaid | Reference | |||

| Insured or no specifics | 0.860(0.746–0.992) | 0.038 | ||

| Uninsured | 1.046(0.598–1.832) | 0.874 | ||

| Unknown | 0.924(0.799–1.067) | 0.281 | ||

| Marital status | <0.001 | 0.007 | ||

| Married or domestic partner | Reference | Reference | ||

| Divorced/separated/single/widowed | 1.154(1.079–1.234) | <0.001 | 1.121(1.042–1.205) | 0.002 |

| Unknown | 1.087(0.911–1.298) | 0.355 | 1.127(0.940–1.351) | 0.198 |

| High School education (%) | 0.089 | |||

| ≤10 | Reference | |||

| >10, ≤20 | 1.044(0.953–1.143) | 0.356 | ||

| >20, ≤30 | 1.128(1.021–1.248) | 0.018 | ||

| >30 | 1.089(0.888–1.335) | 0.413 | ||

| Unknown | ||||

| Median family income (dollar, in tens) | 0.012 | 0.360 | ||

| ≤5000 | Reference | Reference | ||

| >5000, ≤7000 | 1.026(0.934–1.126) | 0.591 | 1.077(0.979–1.184) | 0.127 |

| >7000, ≤9000 | 0.917(0.826–1.019) | 0.109 | 1.072(0.961–1.195) | 0.211 |

| >9000 | 0.886(0.771–1.018) | 0.087 | 1.006(0.874–1.159) | 0.932 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yao, A.; Liang, L.; Rao, H.; Shen, Y.; Wang, C.; Xie, S. The Clinical Characteristics and Treatments for Large Cell Carcinoma Patients Older than 65 Years Old: A Population-Based Study. Cancers 2022, 14, 5231. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14215231

Yao A, Liang L, Rao H, Shen Y, Wang C, Xie S. The Clinical Characteristics and Treatments for Large Cell Carcinoma Patients Older than 65 Years Old: A Population-Based Study. Cancers. 2022; 14(21):5231. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14215231

Chicago/Turabian StyleYao, Anjie, Long Liang, Hanyu Rao, Yilun Shen, Changhui Wang, and Shuanshuan Xie. 2022. "The Clinical Characteristics and Treatments for Large Cell Carcinoma Patients Older than 65 Years Old: A Population-Based Study" Cancers 14, no. 21: 5231. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14215231

APA StyleYao, A., Liang, L., Rao, H., Shen, Y., Wang, C., & Xie, S. (2022). The Clinical Characteristics and Treatments for Large Cell Carcinoma Patients Older than 65 Years Old: A Population-Based Study. Cancers, 14(21), 5231. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14215231