Midline Skull Base Meningiomas: Transcranial and Endonasal Perspectives

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Definition of Surgical Corridors

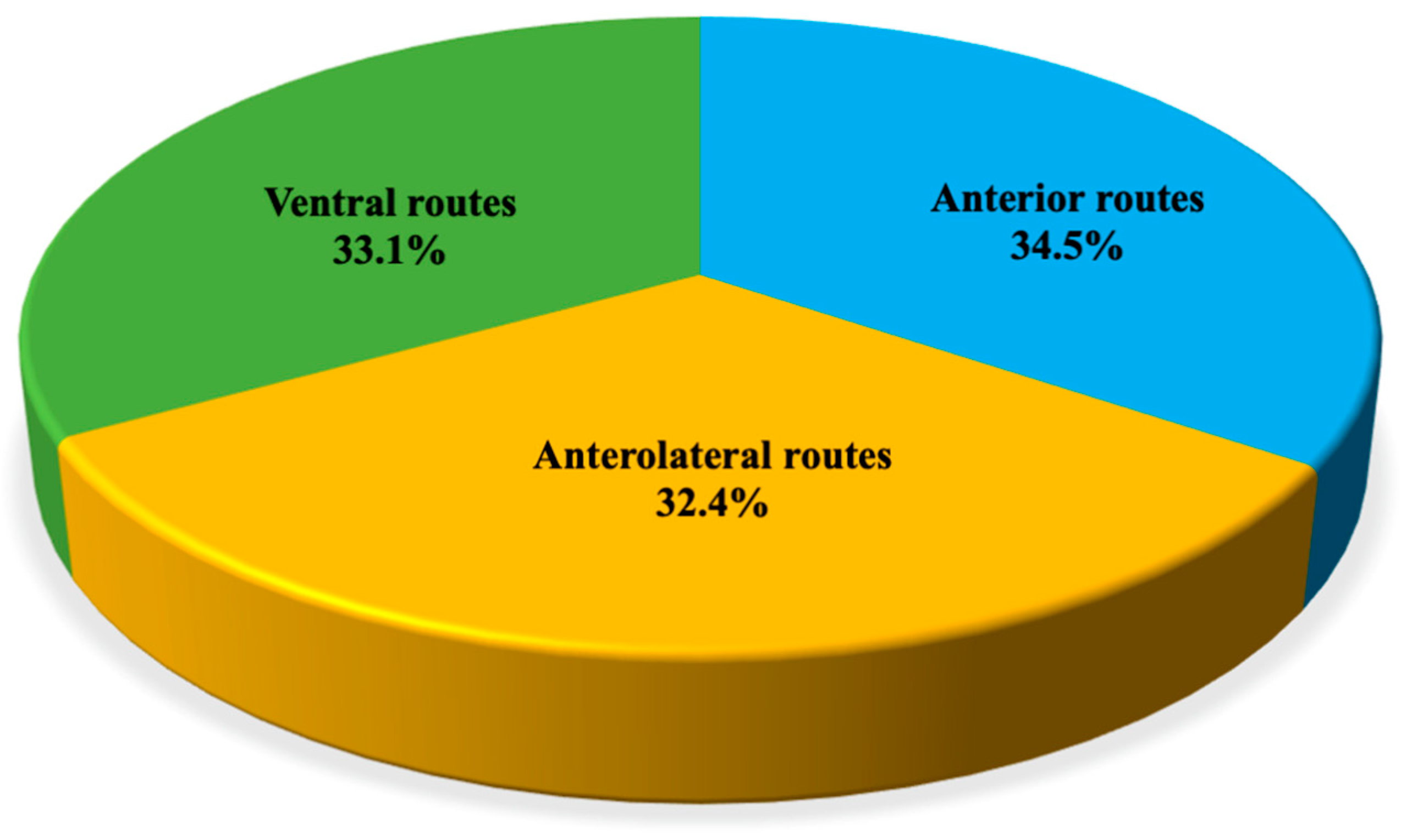

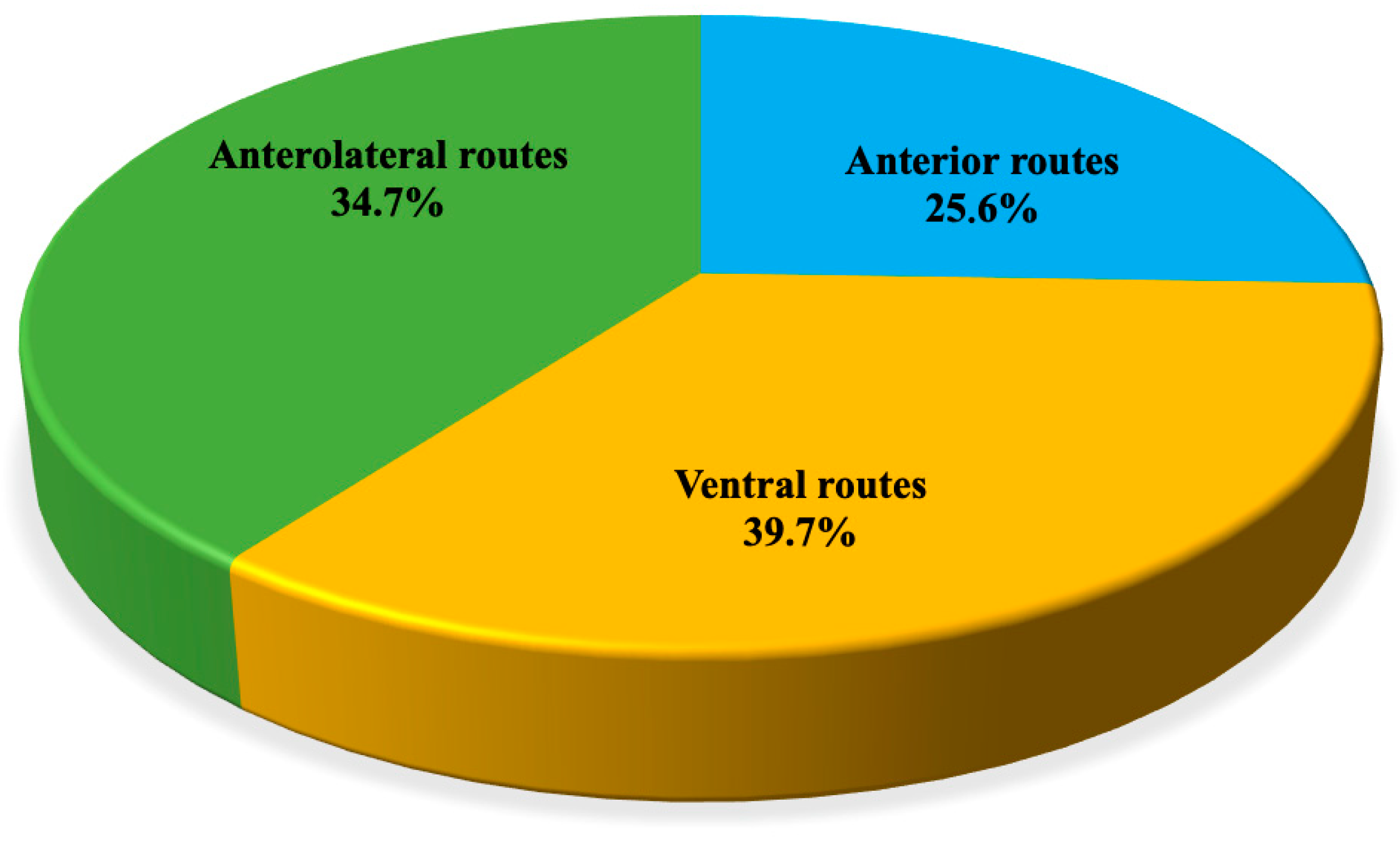

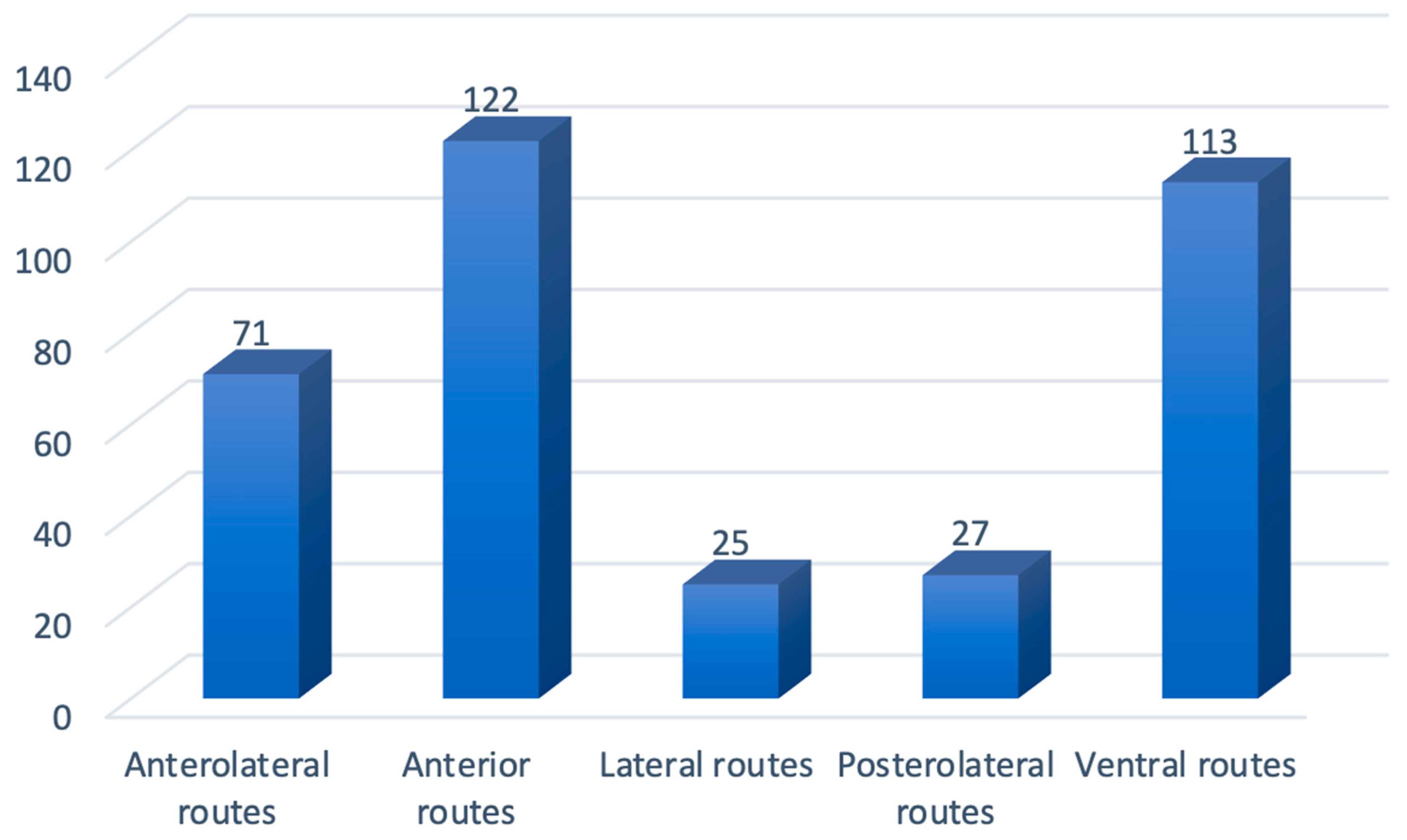

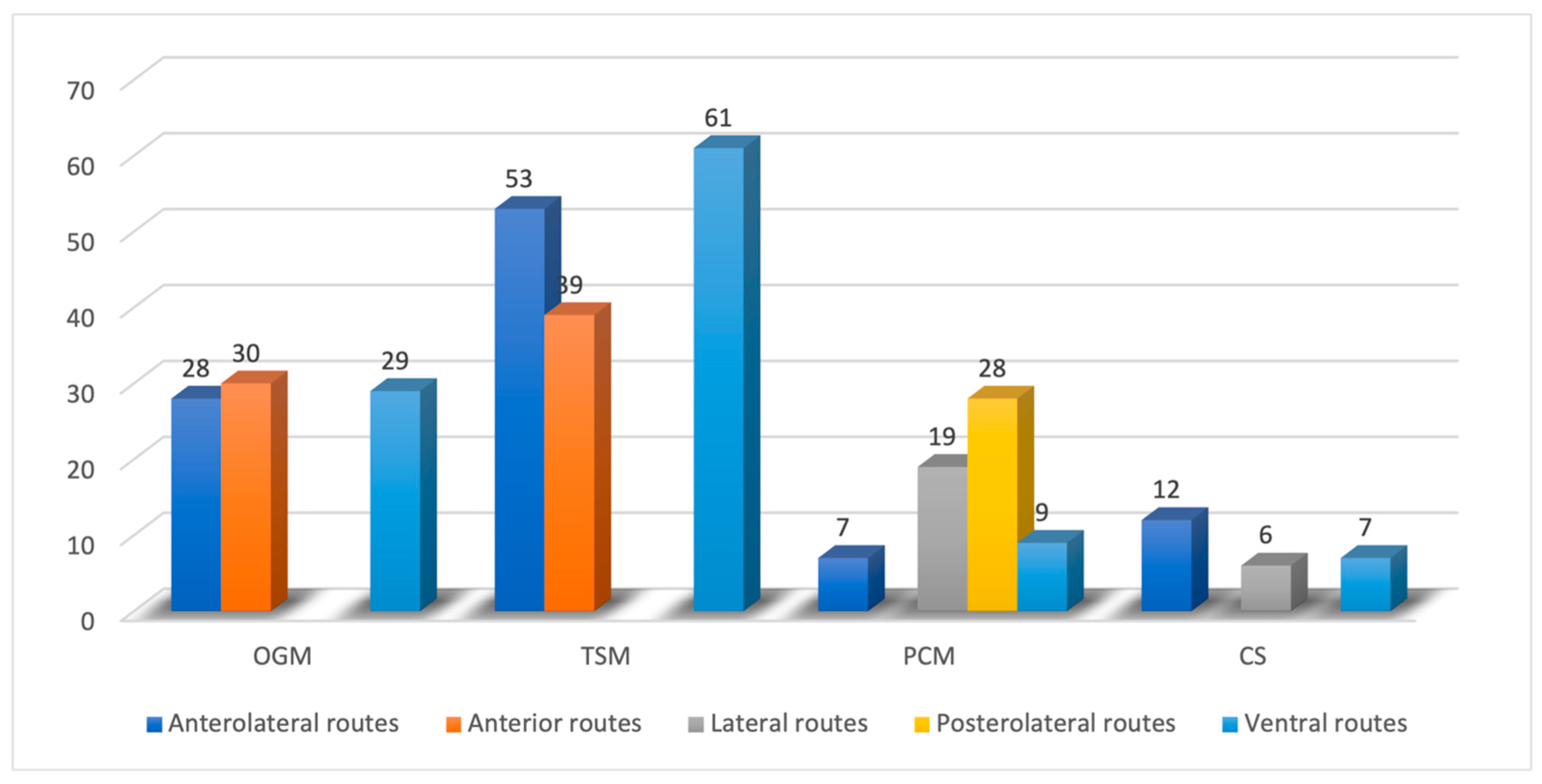

3. Results

4. Discussion

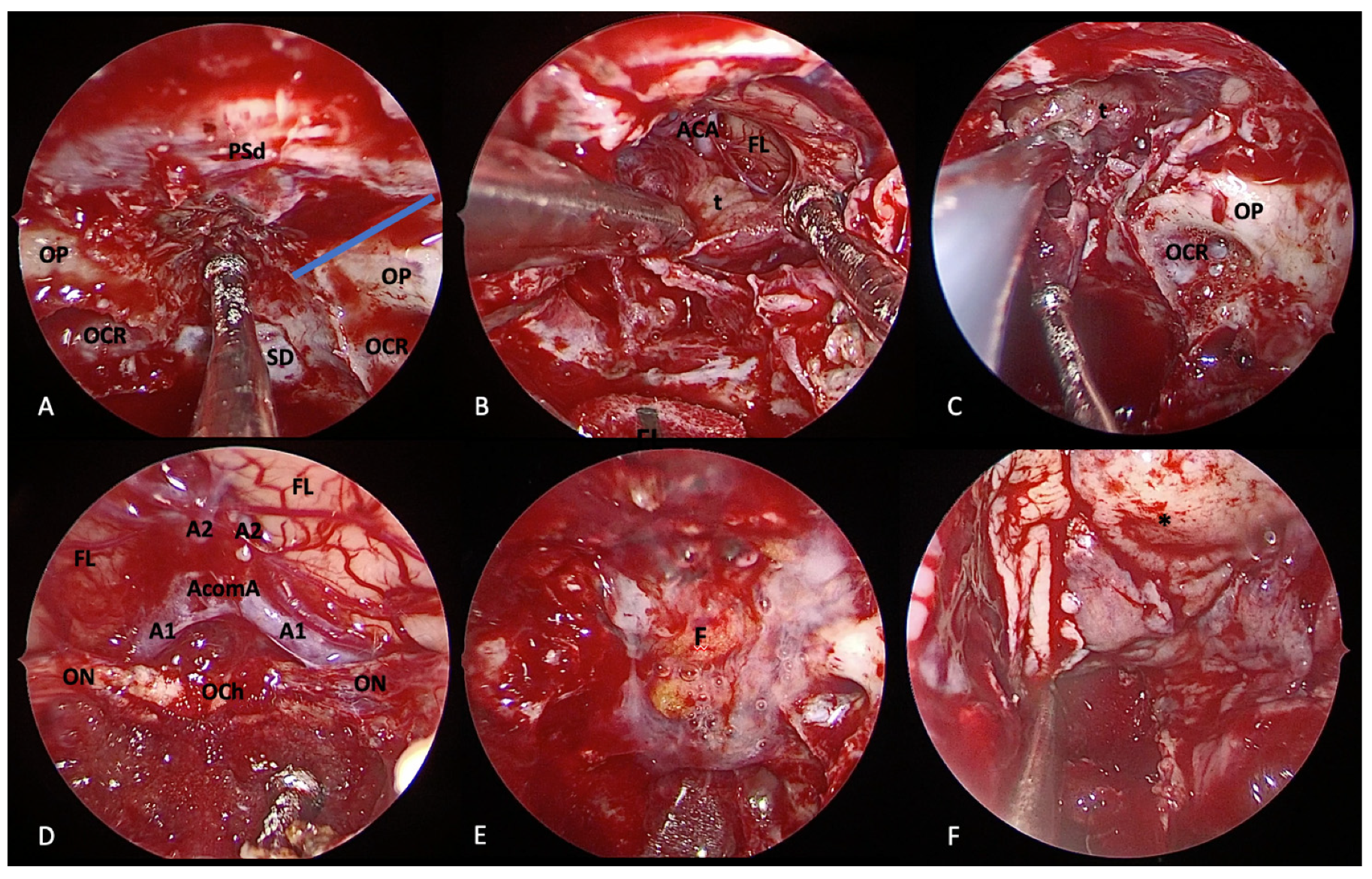

4.1. Olfactory Groove Meningiomas

4.1.1. Transcranial Perspective

4.1.2. Endoscopic Endonasal Perspective

4.1.3. EEA vs. Transcranial

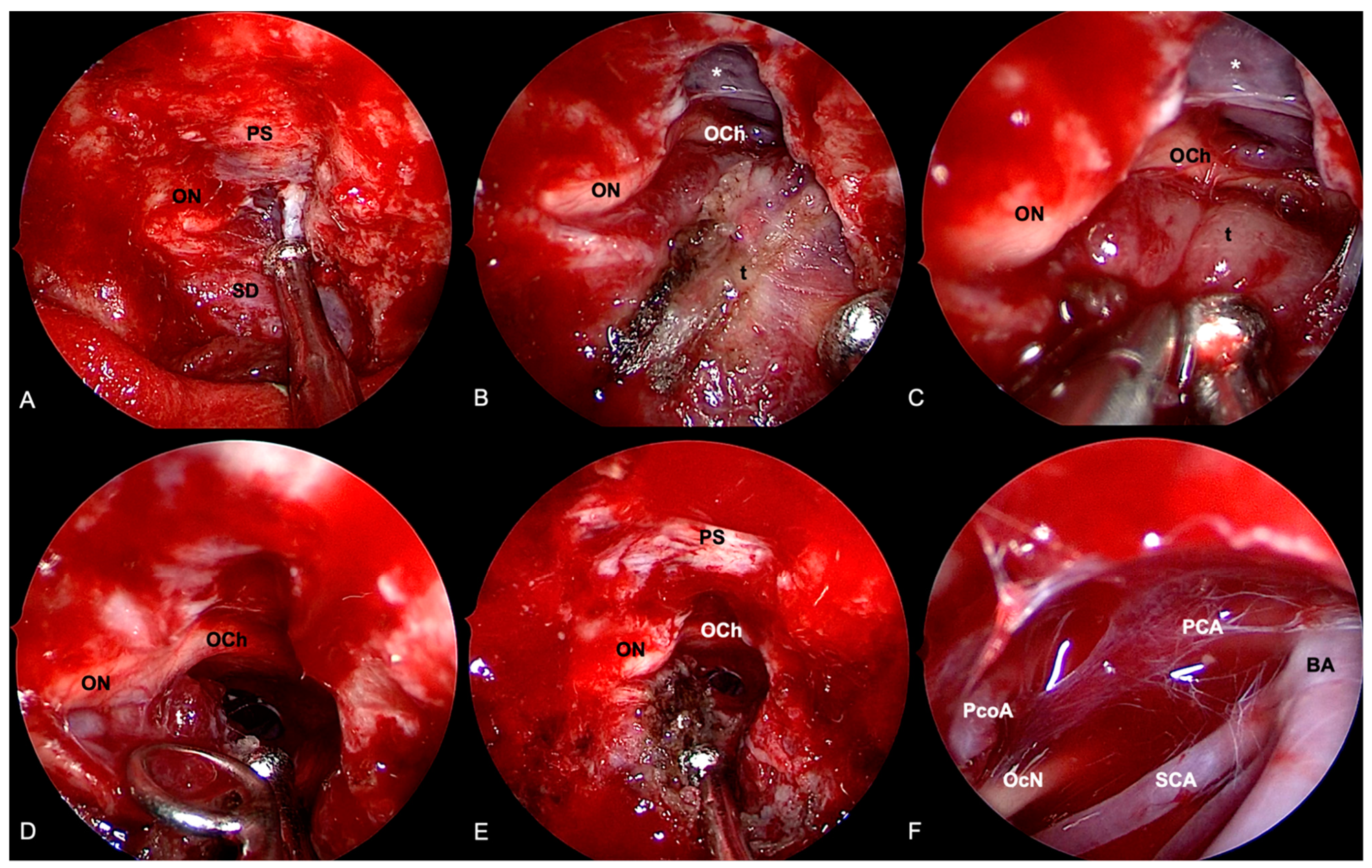

4.2. Tuberculum Sellae/Planum Sphenoidale Meningiomas

4.2.1. Transcranial Perspective

4.2.2. Endoscopic Endonasal Perspective

4.2.3. EEA vs. Transcranial

4.3. Clival and Petroclival Meningiomas

4.3.1. Transcranial Perspective

4.3.2. Endoscopic Endonasal Perspective

4.3.3. EEA vs. Transcranial

4.4. Cavernous Sinus Meningiomas

4.4.1. Transcranial Perspective

4.4.2. Endoscopic Endonasal Perspective

4.4.3. EEA vs. Transcranial

4.5. Management Evolution

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- de Divitiis, E.; Cavallo, L.M.; Esposito, F.; Stella, L.; Messina, A. Extended Endoscopic Transsphenoidal Approach for Tuberculum Sellae Meningiomas. Neurosurgery 2008, 62, SHC1192–SHC1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adappa, N.D.; Lee, J.Y.; Chiu, A.G.; Palmer, J.N. Olfactory Groove Meningioma. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2011, 44, 965–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aftahy, A.; Barz, M.; Krauss, P.; Wagner, A.; Lange, N.; Hijazi, A.; Wiestler, B.; Meyer, B.; Negwer, C.; Gempt, J. Midline Meningiomas of the Anterior Skull Base: Surgical Outcomes and a Decision-Making Algorithm for Classic Skull Base Approaches. Cancers 2020, 12, 3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Aguiar, P.H.P.; Tahara, A.; Almeida, A.N.; Simm, R.; da Silva, A.N.; Maldaun, M.V.C.; Panagopoulos, A.T.; Zicarelli, C.A.; Silva, P.G. Olfactory groove meningiomas: Approaches and complications. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2009, 16, 1168–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayad, T.; Khoueir, P.; Saliba, I.; Moumdjian, R. Cacosmia secondary to an olfactory groove meningioma. J. Otolaryngol. Suppl. 2007, 36, E21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Fiki, M. Surgical Anatomy for Control of Ethmoidal Arteries During Extended Endoscopic Endonasal or Microsurgical Resection of Vascular Anterior Skull Base Meningiomas. World Neurosurg. 2015, 84, 1532–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, A.Y.; Wong, S.; Saluja, S.; Jin, M.C.; Thai, A.; Pendharkar, A.V.; Ho, A.L.; Reddy, P.; Efron, A.D. Resection of Olfactory Groove Meningiomas Through Unilateral vs. Bilateral Approaches: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 560706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiramatsu, M.; Sugiu, K.; Hishikawa, T.; Haruma, J.; Takahashi, Y.; Murai, S.; Nishi, K.; Yamaoka, Y.; Shimazu, Y.; Fujii, K.; et al. Detailed Arterial Anatomy and Its Anastomoses of the Sphenoid Ridge and Olfactory Groove Meningiomas with Special Reference to the Recurrent Branches from the Ophthalmic Artery. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2020, 41, 2082–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banu, M.A.; Mehta, A.; Ottenhausen, M.; Fraser, J.F.; Patel, K.S.; Szentirmai, O.; Anand, V.K.; Tsiouris, A.J.; Schwartz, T.H. Endoscope-assisted endonasal versus supraorbital keyhole resection of olfactory groove meningiomas: Comparison and combination of 2 minimally invasive approaches. J. Neurosurg. 2016, 124, 605–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngerman, B.E.; Shtayer, L.; Gerges, M.M.; Larsen, A.G.; Tomasiewicz, H.C.; Schwartz, T.H. Eyebrow supraorbital keyhole craniotomy for olfactory groove meningiomas with endoscope assistance: Case series and systematic review of extent of resection, quantification of postoperative frontal lobe injury, anosmia, and recurrence. Acta Neurochir. 2020, 163, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downes, A.E.; Freeman, J.L.; Ormond, D.R.; Lillehei, K.O.; Youssef, A.S. Unilateral Tailored Fronto-Orbital Approach for Giant Olfactory Groove Meningiomas: Technical Nuances. World Neurosurg. 2015, 84, 1166–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eroglu, U.; Shah, K.; Bozkurt, M.; Kahilogullari, G.; Yakar, F.; Doğan, I.; Ozgural, O.; Attar, A.; Unlu, A.; Caglar, S.; et al. Supraorbital Keyhole Approach: Lessons Learned from 106 Operative Cases. World Neurosurg. 2019, 124, e667–e674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, D.Z.; Muskens, I.S.; Mekary, R.A.; Najafabadi, A.H.Z.; Helmy, A.E.; Reisch, R.; Broekman, M.L.D.; Marcus, H.J. The endoscope-assisted supraorbital “keyhole” approach for anterior skull base meningiomas: An updated meta-analysis. Acta Neurochir. 2020, 163, 661–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cecchini, G. Anterior and Posterior Ethmoidal Artery Ligation in Anterior Skull Base Meningiomas: A Review on Microsurgical Approaches. World Neurosurg. 2015, 84, 1161–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pallini, R.; Fernandez, E.; Lauretti, L.; Doglietto, F.; D’Alessandris, Q.G.; Montano, N.; Capo, G.; Meglio, M.; Maira, G. Olfactory Groove Meningioma: Report of 99 Cases Surgically Treated at the Catholic University School of Medicine, Rome. World Neurosurg. 2015, 83, 219–231.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachinger, W.; Grau, S.; Tonn, J.-C. Different microsurgical approaches to meningiomas of the anterior cranial base. Acta Neurochir. 2010, 152, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefini, R.; Zenga, F.; Giacomo, E.; Bolzoni, A.; Tartara, F.; Spena, G.; Ambrosi, C.; Fontanella, M.M. Following the canyon to reach and remove olfactory groove meningiomas. J. Neurosurg. Sci. 2016, 61, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenga, F.; Penner, F.; Cofano, F.; Lavorato, A.; Tardivo, V.; Fontanella, M.; Garbossa, D.; Stefini, R. Trans-Frontal Sinus Approach For Olfactory Groove Meningiomas: A 19 Year Experience. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2020, 196, 106041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Divitiis, O.; Di Somma, A.; Cavallo, L.M.; Cappabianca, P. Tips and Tricks for Anterior Cranial Base Reconstruction. Acta Neurochir. Suppl. 2017, 124, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasello, F.; Angileri, F.F.; Grasso, G.; Granata, F.; De Ponte, F.S.; Alafaci, C. Giant Olfactory Groove Meningiomas: Extent of Frontal Lobes Damage and Long-Term Outcome After the Pterional Approach. World Neurosurg. 2011, 76, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spektor, S.; Valarezo, J.; Fliss, D.M.; Gil, Z.; Cohen, J.; Goldman, J.; Umansky, F. Olfactory Groove Meningiomas from Neurosurgical and Ear, Nose, and Throat Perspectives: Approaches, Techniques, and Outcomes. Oper. Neurosurg. 2005, 57, ONS-268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Bahy, K. Validity of the frontolateral approach as a minimally invasive corridor for olfactory groove meningiomas. Acta Neurochir. 2009, 151, 1197–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Valero, S.F.; Van Gompel, J.J.; Loumiotis, I.; Lanzino, G. Craniotomy for anterior cranial fossa meningiomas: Historical overview. Neurosurg. Focus 2014, 36, E14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, J.C.; Gonçalves, M.B.; Pereira, C.E.; Melo, W.; Temponi, G.F. The extended pterional approach allows excellent results for removal of anterior cranial fossa meningiomas. Arq. Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2016, 74, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendricks, B.K.; Cohen-Gadol, A.A. The Extended Pterional Craniotomy: A Contemporary and Balanced Approach. Oper. Neurosurg. 2019, 18, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitter, A.D.; Stavrinou, L.C.; Ntoulias, G.; Dukagjin, M.; Scholz, M.; Hassler, W.; Petridis, A.K. The Role of the Pterional Approach in the Surgical Treatment of Olfactory Groove Meningiomas: A 20-year Experience. J. Neurol. Surg. Part B Skull Base 2013, 74, 097–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeciusova, M.; Svoboda, N.; Benes, V.; Astl, J.; Netuka, D. Olfaction in Olfactory Groove Meningiomas. J. Neurol. Surg. Part A Cent. Eur. Neurosurg. 2020, 81, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Thakur, B.; Corns, R.; Connor, S.; Bhangoo, R.; Ashkan, K.; Gullan, R. Resection of olfactory groove meningioma—A review of complications and prognostic factors. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2015, 29, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colli, B.O.; Junior, C.C.; Junior, J.A.A.; Dos Santos, M.B.M.; Neder, L.; Dos Santos, A.C.; Batagini, N.C. Olfactory groove meningiomas: Surgical technique and follow-up review. Arq. Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2007, 65, 795–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, G.; Ben David, U.; Gornish, M.; Rappaport, Z.H. Meningiomas of the anterior cranial fossa floor. Acta Neurochir. 1994, 129, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbassy, M.; Woodard, T.D.; Sindwani, R.; Recinos, P.F. An Overview of Anterior Skull Base Meningiomas and the Endoscopic Endonasal Approach. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 49, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.K.; Christiano, L.D.; Patel, S.K.; Tubbs, R.S.; Eloy, J.A. Surgical nuances for removal of olfactory groove meningiomas using the endoscopic endonasal transcribriform approach. Neurosurg. Focus 2011, 30, E3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroeder, H.W. Indications and Limitations of the Endoscopic Endonasal Approach for Anterior Cranial Base Meningiomas. World Neurosurg. 2014, 82, S81–S85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ocak, P.E.; Yilmazlar, S. Retrosigmoid Transtentorial Resection of a Petroclival Meningioma: 2-Dimensional Operative Video. Oper. Neurosurg. 2019, 18, E80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, P.A.; Kassam, A.B.; Thomas, A.; Snyderman, C.H.; Carrau, R.L.; Mintz, A.H.; Prevedello, D.M. ENDOSCOPIC ENDONASAL RESECTION OF ANTERIOR CRANIAL BASE MENINGIOMAS. Neurosurgery 2008, 63, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komotar, R.J.; Starke, R.M.; Raper, D.M.S.; Anand, V.K.; Schwartz, T.H. Endoscopic skull base surgery: A comprehensive comparison with open transcranial approaches. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2012, 26, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majmundar, N.; Naveed, H.K.; Reddy, K.R.; Eloy, J.A.; James, K. Liulimitations of the endoscopic endonasal transcribriform approach. J. Neurosurg. Sci. 2018, 62, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunworth, J.; Padhye, V.; Bassiouni, A.; Psaltis, A.; Floreani, S.; Robinson, S.; Santoreneos, S.; Vrodos, N.; Parker, A.; Wickremesekera, A.; et al. Update on endoscopic endonasal resection of skull base meningiomas. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2014, 5, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhye, V.; Naidoo, Y.; Alexander, H.; Floreani, S.; Robinson, S.; Santoreneos, S.; Wickremesekera, A.; Brophy, B.; Harding, M.; Vrodos, N.; et al. Endoscopic Endonasal Resection of Anterior Skull Base Meningiomas. Otolaryngol. Neck Surg. 2012, 147, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutourousiou, M.; Fernandez-Miranda, J.C.; Wang, E.; Snyderman, C.H.; Gardner, P.A. Endoscopic endonasal surgery for olfactory groove meningiomas: Outcomes and limitations in 50 patients. Neurosurg. Focus 2014, 37, E8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Miranda, J.C.; Gardner, P.A.; Prevedello, D.M.; Kassam, A.B. Expanded endonasal approach for olfactory groove meningioma. Acta Neurochir. 2009, 151, 287–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sughrue, M.; Bonney, P.; Burks, J.; Hayhurst, C.; Gore, P.; Teo, C. Results with expanded endonasal resection of skull base meningiomas: Technical nuances and approach selection based on an early experience. Turk. Neurosurg. 2016, 26, 662–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Khan, O.H.; Krischek, B.; Holliman, D.; Klironomos, G.; Kucharczyk, W.; Vescan, A.; Gentili, F.; Zadeh, G. Pure endoscopic expanded endonasal approach for olfactory groove and tuberculum sellae meningiomas. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2014, 21, 927–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prosser, J.D.; Vender, J.R.; Alleyne, C.H.; Solares, C.A. Expanded Endoscopic Endonasal Approaches to Skull Base Meningiomas. J. Neurol. Surg. Part B Skull Base 2012, 73, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Najafabadi, A.H.Z.; Khan, D.Z.; Muskens, I.S.; Broekman, M.L.D.; Dorward, N.L.; van Furth, W.R.; Marcus, H.J. Trends in cerebrospinal fluid leak rates following the extended endoscopic endonasal approach for anterior skull base meningioma: A meta-analysis over the last 20 years. Acta Neurochir. 2020, 163, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Algattas, H.N.; Wang, E.W.; Zenonos, G.A.; Snyderman, C.H.; Gardner, P.A. Endoscopic endonasal surgery for anterior cranial fossa meningiomas. J. Neurosurg. Sci. 2021, 65, 118–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsikoudas, A.; Martin-Hirsch, D.P. Olfactory groove meningiomas. Clin. Otolaryngol. 1999, 24, 507–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welge-Luessen, A.; Temmel, A.; Quint, C.; Moll, B.; Wolf, S.; Hummel, T. Olfactory function in patients with olfactory groove meningioma. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2001, 70, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappabianca, P.; Cavallo, L.M.; Esposito, F.; de Divitiis, O.; Messina, A. Extended endoscopic endonasal approach to the midline skull base: The evolving role of transsphenoidal surgery. Adv. Tech. Stand. Neurosurg. 2008, 33, 151–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, L.M.; Messina, A.; Esposito, F.; De Divitiis, O.; Fabbro, M.D.; De Divitiis, E.; Cappabianca, P. Skull base reconstruction in the extended endoscopic transsphenoidal approach for suprasellar lesions. J. Neurosurg. 2007, 107, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, L.M.; Solari, D.; Somma, T.; Savic, D.; Cappabianca, P. The Awake Endoscope-Guided Sealant Technique with Fibrin Glue in the Treatment of Postoperative Cerebrospinal Fluid Leak After Extended Transsphenoidal Surgery: Technical Note. World Neurosurg. 2014, 82, e479–e485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavallo, L.M.; Somma, T.; Solari, D.; Iannuzzo, G.; Frio, F.; Baiano, C.; Cappabianca, P. Endoscopic Endonasal Transsphenoidal Surgery: History and Evolution. World Neurosurg. 2019, 127, 686–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavallo, L.M.; Solari, D.; Somma, T.; Cappabianca, P. The 3F (Fat, Flap, and Flash) Technique For Skull Base Reconstruction After Endoscopic Endonasal Suprasellar Approach. World Neurosurg. 2019, 126, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottenhausen, M.; Rumalla, K.; Alalade, A.F.; Nair, P.; La Corte, E.; Younus, I.; Forbes, J.A.; Ben Nsir, A.; Banu, M.A.; Tsiouris, A.J.; et al. Decision-making algorithm for minimally invasive approaches to anterior skull base meningiomas. Neurosurg. Focus 2018, 44, E7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orgain, C.A.; Kuan, E.C.; Alvarado, R.; Adappa, N.D.; Jonker, B.P.; Lee, J.Y.K.; Palmer, J.N.; Winder, M.; Harvey, R.J. Smell Preservation following Unilateral Endoscopic Transnasal Approach to Resection of Olfactory Groove Meningioma: A Multi-institutional Experience. J. Neurol. Surg. Part B Skull Base 2019, 81, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purohit, A.; Jha, R.; Khalafallah, A.M.; Price, C.; Rowan, N.R.; Mukherjee, D. Endoscopic endonasal versus transcranial approach to resection of olfactory groove meningiomas: A systematic review. Neurosurg. Rev. 2019, 43, 1465–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, S.R.; Treviño, A.S.R.; Omay, S.B.; Almeida, J.P.; Liang, B.; Chen, Y.-N.; Singh, H.; Schwartz, T.H. Limitations of the endonasal endoscopic approach in treating olfactory groove meningiomas. A systematic review. Acta Neurochir. 2017, 159, 1875–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortazavi, M.M.; da Silva, H.B.; Ferreira, M.; Barber, J.K.; Pridgeon, J.S.; Sekhar, L.N. Planum Sphenoidale and Tuberculum Sellae Meningiomas: Operative Nuances of a Modern Surgical Technique with Outcome and Proposal of a New Classification System. World Neurosurg. 2015, 86, 270–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.-K.; Jung, H.-W.; Yang, S.-Y.; Seol, H.J.; Paek, S.H.; Kim, D.G. Surgically Treated Tuberculum Sellae and Diaphragm Sellae Meningiomas: The Importance of Short-term Visual Outcome. Neurosurgery 2006, 59, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, A.; Muzumdar, D.; Desai, K.I. Tuberculum sellae meningioma: A report on management on the basis of a surgical expe-rience with 70 patients. Neurosurgery 2002, 51, 1358–1363; discussion 1363–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magill, S.; Morshed, R.A.; Lucas, C.-H.G.; Aghi, M.K.; Theodosopoulos, P.V.; Berger, M.S.; De Divitiis, O.; Solari, D.; Cappabianca, P.; Cavallo, L.M.; et al. Tuberculum sellae meningiomas: Grading scale to assess surgical outcomes using the transcranial versus transsphenoidal approach. Neurosurg. Focus 2018, 44, E9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youngerman, B.E.; Banu, M.A.; Gerges, M.M.; Odigie, E.; Tabaee, A.; Kacker, A.; Anand, V.K.; Schwartz, T.H. Endoscopic endonasal approach for suprasellar meningiomas: Introduction of a new scoring system to predict extent of resection and assist in case selection with long-term outcome data. J. Neurosurg. 2020, 135, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borghei-Razavi, H.; Lee, J.; Ibrahim, B.; Muhsen, B.A.; Raghavan, A.; Wu, I.; Poturalski, M.; Stock, S.; Karakasis, C.; Adada, B.; et al. Accuracy and Interrater Reliability of CISS Versus Contrast-Enhanced T1-Weighted VIBE for the Presence of Optic Canal Invasion in Tuberculum Sellae Meningiomas. World Neurosurg. 2021, 148, e502–e507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Divitiis, E.; Esposito, F.; Cappabianca, P.; Cavallo, L.M.; de Divitiis, O. TUBERCULUM SELLAE MENINGIOMAS. Neurosurgery 2008, 62, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karsy, M.; Raheja, A.; Eli, I.; Guan, J.; Couldwell, W.T. Clinical Outcomes with Transcranial Resection of the Tuberculum Sellae Meningioma. World Neurosurg. 2017, 108, 748–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chokyu, I.; Goto, T.; Ishibashi, K.; Nagata, T.; Ohata, K. Bilateral subfrontal approach for tuberculum sellae meningiomas in long-term postoperative visual outcome. J. Neurosurg. 2011, 115, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, M.; Roser, F.; Struck, M.; Vorkapic, P.; Samii, M. TUBERCULUM SELLAE MENINGIOMAS. Neurosurgery 2006, 59, 1019–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, W.-Y.; Jung, S.; Jung, T.-Y.; Moon, K.-S.; Kim, I.-Y. The contralateral subfrontal approach can simplify surgery and provide favorable visual outcome in tuberculum sellae meningiomas. Neurosurg. Rev. 2012, 35, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Shen, J.; Zhang, L.; Yang, J.; Weng, Y.; Fang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Ye, H.; Zhan, R.; Zheng, X. Unilateral Subfrontal Approach for Giant Tuberculum Sellae Meningioma: Single Center Experience and Review of the Literature. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 708235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igressa, A.; Pechlivanis, I.; Weber, F.; Mahvash, M.; Ayyad, A.; Boutarbouch, M.; Charalampaki, P. Endoscope-assisted keyhole surgery via an eyebrow incision for removal of large meningiomas of the anterior and middle cranial fossa. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2015, 129, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisch, R.; Perneczky, A.; Filippi, R. Surgical technique of the supraorbital key-hole craniotomy. Surg. Neurol. 2003, 59, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallari, R.J.; Thakur, J.D.; Rhee, J.H.; Eisenberg, A.; Krauss, H.; Griffiths, C.; Sivakumar, W.; Barkhoudarian, G.; Kelly, D.F. Endoscopic Endonasal and Supraorbital Removal of Tuberculum Sellae Meningiomas: Anatomic Guides and Operative Nuances for Keyhole Approach Selection. Oper. Neurosurg. 2021, 21, E71–E81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, M.; Nader, R.; Al-Mefty, O. Optic Canal Involvement in Tuberculum Sellae Meningiomas. Neurosurg. 2010, 67, ons108–ons119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attia, M.; Umansky, F.; Paldor, I.; Dotan, S.; Shoshan, Y.; Spektor, S. Giant anterior clinoidal meningiomas: Surgical technique and outcomes. J. Neurosurg. 2012, 117, 654–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneau, M.; Grenier-Chantrand, F.; Riva, M. How I do it: Anterior interhemispheric approach to tuberculum sellae meningiomas. Acta Neurochir. 2021, 163, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.K.; Kramer, D.E.; Wong, R.H. Keyhole superior interhemispheric transfalcine approach for tuberculum sellae meningioma: Technical nuances and visual outcomes. World Neurosurg. 2020, 145, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curey, S.; Derrey, S.; Hannequin, P.; Hannequin, D.; Fréger, P.; Muraine, M.; Castel, H.; Proust, F. Validation of the superior interhemispheric approach for tuberculum sellae meningioma. J. Neurosurg. 2012, 117, 1013–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévêque, S.; Derrey, S.; Martinaud, O.; Gérardin, E.; Langlois, O.; Fréger, P.; Hannequin, D.; Castel, H.; Proust, F. Superior interhemispheric approach for midline meningioma from the anterior cranial base. Neurochirurgie 2011, 57, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terasaka, S.; Asaoka, K.; Kobayashi, H.; Yamaguchi, S. Anterior Interhemispheric Approach for Tuberculum Sellae Meningioma. Neurosurg. 2011, 68, ons84–ons89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganna, A.; Dehdashti, A.R.; Karabatsou, K.; Gentili, F. Fronto-basal interhemispheric approach for tuberculum sellae meningiomas; long-term visual outcome. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2009, 23, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, V.; Russell, S.M. The Microsurgical Nuances of Resecting Tuberculum Sellae Meningiomas. Oper. Neurosurg. 2005, 56, ONS-411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- I Jallo, G.; Benjamin, V. Tuberculum sellae meningiomas: Microsurgical anatomy and surgical technique. Neurosurgery 2002, 51, 1432–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Liu, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, S. Surgical management of Tuberculum sellae meningiomas. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2007, 14, 1150–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mardjono, I.; Faried, A.; Sidabutar, R.; Wirjomartani, B.A.; Arifin, M.Z. Pterional approach versus unilateral frontal approach on tuberculum sellae meningioma: Single centre experiences. Asian J. Neurosurg. 2012, 7, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Romani, R.; Laakso, A.; Kangasniemi, M.; Niemelä, M.; Hernesniemi, J. Lateral Supraorbital Approach Applied to Tuberculum Sellae Meningiomas. Neurosurgery 2012, 70, 1504–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troude, L.; Boucekine, M.; Baucher, G.; Farah, K.; Boissonneau, S.; Fuentes, S.; Graillon, T.; Dufour, H. Ipsilateral vs controlateral approach in tuberculum sellae meningiomas surgery: A retrospective comparative study. Neurosurg. Rev. 2021, 44, 3581–3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bander, E.D.; Singh, H.; Ogilvie, C.B.; Cusic, R.C.; Pisapia, D.J.; Tsiouris, A.J.; Anand, V.K.; Schwartz, T.H. Endoscopic endonasal versus transcranial approach to tuberculum sellae and planum sphenoidale meningiomas in a similar cohort of patients. J. Neurosurg. 2018, 128, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Xu, T.; Wu, X.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. The expanded endoscopic endonasal approach for treatment of tuberculum sellae meningiomas in a series of 40 consecutive cases. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, L.M.; de Divitiis, O.; Aydin, S.; Messina, A.; Esposito, F.; Iaconetta, G.; Talat, K.; Cappabianca, P.; Tschabitscher, M. Extended endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal approach to the suprasellar area. Neurosurgery 2007, 61, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Somma, A.; Torales, J.; Cavallo, L.M.; Pineda, J.; Solari, D.; Gerardi, R.M.; Frio, F.; Enseñat, J.; Prats-Galino, A.; Cappabianca, P. Defining the lateral limits of the endoscopic endonasal transtuberculum transplanum approach: Anatomical study with pertinent quantitative analysis. J. Neurosurg. 2019, 130, 848–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Notaris, M.; Solari, D.; Cavallo, L.M.; D’Enza, A.I.; Enseñat, J.; Berenguer, J.; Ferrer, E.; Prats-Galino, A.; Cappabianca, P. The “suprasellar notch,” or the tuberculum sellae as seen from below: Definition, features, and clinical implications from an endoscopic endonasal perspective. J. Neurosurg. 2012, 116, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deopujari, C. Endoscopic Endonasal Excision of Craniopharyngiomas. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mTXsV1Nxw2M (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Hadad, G.; Bassagasteguy, L.; Carrau, R.L.; Mataza, J.C.; Kassam, A.; Snyderman, C.H.; Mintz, A. A Novel Reconstructive Technique After Endoscopic Expanded Endonasal Approaches: Vascular Pedicle Nasoseptal Flap. Laryngoscope 2006, 116, 1882–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadad, G.; Rivera-Serrano, C.M.; Bassagaisteguy, L.H.; Carrau, R.L.; Fernandez-Miranda, J.; Prevedello, D.M.; Kassam, A.B. Anterior pedicle lateral nasal wall flap: A novel technique for the reconstruction of anterior skull base defects. Laryngoscope 2011, 121, 1606–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guaraldi, F.; Pasquini, E.; Frank, G.; Mazzatenta, D.; Zoli, M. The Endoscopic Endonasal Management of Anterior Skull Base Meningiomas. J. Neurol. Surg. Part B Skull Base 2018, 79, S300–S310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Fan, Y.; Shen, Z.; Wang, R.; Bao, X. Transsphenoidal versus Transcranial Approach for Treatment of Tuberculum Sellae Meningiomas: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Comparative Studies. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowers, C.A.; Altay, T.; Couldwell, W.T. Surgical decision-making strategies in tuberculum sellae meningioma resection. Neurosurg. Focus 2011, 30, E1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setty, P.; Fernandez-Miranda, J.C.; Wang, E.W.; Snyderman, C.H.; Gardner, P.A. Residual and Recurrent Disease Following Endoscopic Endonasal Approach as a Reflection of Anatomic Limitation for the Resection of Midline Anterior Skull Base Meningiomas. Oper. Neurosurg. 2021, 21, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, G.; Pasquini, E. Tuberculum Sellae Meningioma: The Extended Transsphenoidal Approach—For the Virtuoso Only? World Neurosurg. 2010, 73, 625–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitano, M.; Taneda, M.; Nakao, Y. Postoperative improvement in visual function in patients with tuberculum sellae meningiomas: Results of the extended transsphenoidal and transcranial approaches. J. Neurosurg. 2007, 107, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graffeo, C.S.; Dietrich, A.R.; Grobelny, B.; Zhang, M.; Goldberg, J.D.; Golfinos, J.G.; Lebowitz, R.; Kleinberg, D.; Placantonakis, D.G. A panoramic view of the skull base: Systematic review of open and endoscopic endonasal approaches to four tumors. Pituitary 2013, 17, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muskens, I.S.; Briceno, V.; Ouwehand, T.L.; Castlen, J.P.; Gormley, W.B.; Aglio, L.S.; Najafabadi, A.H.Z.; van Furth, W.R.; Smith, T.R.; Mekary, R.A.; et al. The endoscopic endonasal approach is not superior to the microscopic transcranial approach for anterior skull base meningiomas—A meta-analysis. Acta Neurochir. 2017, 160, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almefty, R.; Dunn, I.F.; Pravdenkova, S.; Abolfotoh, M.; Al-Mefty, O. True petroclival meningiomas: Results of surgical management. J. Neurosurg. 2014, 120, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magill, S.T.; Rick, J.W.; Chen, W.C.; Haase, D.A.; Raleigh, D.R.; Aghi, M.K.; Theodosopoulos, P.V.; McDermott, M.W. Petrous Face Meningiomas: Classification, Clinical Syndromes, and Surgical Outcomes. World Neurosurg. 2018, 114, e1266–e1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Yuan, X.; Yuan, J.; Cai, L.; Jiang, W.; Xie, Y.; Wanggou, S.; Zhang, C.; Tang, G.; Li, H.; et al. Treatment Strategy for Petroclival Meningiomas Based on a Proposed Classification in a Study of 168 Cases. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sassun, T.E.; Ruggeri, A.G.; Delfini, R. True Petroclival Meningiomas: Proposal of Classification and Role of the Combined Supra-Infratentorial Presigmoid Retrolabyrinthine Approach. World Neurosurg. 2016, 96, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beniwal, M.; Bhat, D.I.; Rao, N.; Bhagavatula, I.D.; Somanna, S. Surgical management of petroclival meningiomas: Factors affecting early post-operative outcome. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2015, 29, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, F.; Troude, L.; Isnard, S.; Lemée, J.-M.; Terrier, L.; François, P.; Velut, S.; Gay, E.; Fournier, H.-D.; Roche, P.-H. Long term surgical results of 154 petroclival meningiomas: A retrospective multicenter study. Neurochirurgie 2019, 65, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannery, T.J.; Kano, H.; Lunsford, L.D.; Sirin, S.A.; Tormenti, M.; Niranjan, A.; Flickinger, J.; Kondziolka, D. Long-term control of petroclival meningiomas through radiosurgery. J. Neurosurg. 2010, 112, 957–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwai, Y.; Yamanaka, K.; Shimohonji, W.; Ishibashi, K. Staged Gamma Knife Radiosurgery for Large Skull Base Meningiomas. Cureus 2019, 11, e6001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; Kim, D.G.; Se, Y.-B.; Kim, S.K.; Chung, H.-T.; Paek, S.H.; Jung, H.-W. Gamma Knife Radiosurgery for Petroclival Meningioma: Long-Term Outcome and Failure Pattern. Ster. Funct. Neurosurg. 2017, 95, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; Jung, H.-W.; Kim, Y.H.; Park, C.-K.; Chung, H.-T.; Paek, S.H.; Kim, D.G.; Lee, S.H. Petroclival meningiomas: Long-term outcomes of multimodal treatments and management strategies based on 30 years of experience at a single institution. J. Neurosurg. 2020, 132, 1675–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patibandla, M.R.; Lee, C.-C.; Tata, A.; Addagada, G.C.; Sheehan, J.P. Stereotactic radiosurgery for WHO grade I posterior fossa meningiomas: Long-term outcomes with volumetric evaluation. J. Neurosurg. 2018, 129, 1249–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koutourousiou, M.; Fernandez-Miranda, J.C.; Filho, F.V.-G.; de Almeida, J.R.; Wang, E.W.; Snyderman, C.H.; Gardner, P.A. Outcomes of Endonasal and Lateral Approaches to Petroclival Meningiomas. World Neurosurg. 2017, 99, 500–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samii, M.; Tatagiba, M.; Carvalho, G.A. Resection of large petroclival meningiomas by the simple retrosigmoid route. J. Clin. Neurosci. 1999, 6, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Karampelas, I.; Megerian, C.A.; Selman, W.R.; Bambakidis, N.C. Petroclival meningiomas: An update on surgical approaches, decision making, and treatment results. Neurosurg. Focus 2013, 35, E11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samii, M.; Gerganov, V.M. Petroclival Meningiomas: Quo Vadis? World Neurosurg. 2011, 75, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Tang, J.; Ren, C.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, L.-W.; Zhang, J.-T. Surgical management of medium and large petroclival meningiomas: A single institution’s experience of 199 cases with long-term follow-up. Acta Neurochir. 2016, 158, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambakidis, N.C.; Kakarla, U.K.; Kim, L.J.; Nakaji, P.; Porter, R.W.; Daspit, C.P.; Spetzler, R.F. Evolution of surgical approaches in the treatment of petroclival meningiomas. Neurosurg. 2007, 61, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambekar, S.; Amene, C.; Sonig, A.; Guthikonda, B.; Nanda, A. Quantitative Comparison of Retrosigmoid Intradural Suprameatal Approach and Retrosigmoid Transtentorial Approach: Implications for Tumors in the Petroclival Region. J. Neurol. Surg. Part B Skull Base 2013, 74, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostergard, T.A.; Glenn, C.A.; Dekker, S.E.; Pace, J.R.; Bambakidis, N.C. Retrosigmoid Transtentorial Approach: Technical Nuances and Quantification of Benefit From Tentorial Incision. World Neurosurg. 2018, 119, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T.; Katayama, Y.; Fukushima, T.; Kawamata, T. Lateral supracerebellar transtentorial approach for petroclival meningiomas: Operative technique and outcome. J. Neurosurg. 2011, 115, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samii, M.; Tatagiba, M.; Carvalho, G.A. Retrosigmoid intradural suprameatal approach to Meckel’s cave and the middle fossa: Surgical technique and outcome. J. Neurosurg. 2000, 92, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, F.P.K.; Anderson, G.J.; Dogan, A.; Finizio, J.; Noguchi, A.; Liu, K.C.; McMenomey, S.O.; Delashaw, J.B. Extended middle fossa approach: Quantitative analysis of petroclival exposure and surgical freedom as a function of successive temporal bone removal by using frameless stereotaxy. J. Neurosurg. 2004, 100, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horgan, M.A.; Anderson, G.J.; Kellogg, J.X.; Schwartz, M.S.; Spektor, S.; McMenomey, S.O.; Delashaw, J.B. Classification and quantification of the petrosal approach to the petroclival region. J. Neurosurg. 2000, 93, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.W.; Al-Mefty, O. Combined petrosal approach to petroclival meningiomas. Neurosurgery 2002, 51, 708–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essayed, W.I.B.N.; Mooney, M.A.; Al-Mefty, O. Venous Anatomy Influence on the Approach Selection of a Petroclival Clear Cell Meningioma With Associated Multiple Spinal Meningiomas: 2-Dimensional Operative Video. Oper. Neurosurg. 2021, 20, E426–E427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, V.T.G.; Gomes, M.Q.T.; da Roz, L.M.; Yamaki, V.N.; Santo, M.P.D.E.; Teixeira, M.J.; Figueiredo, E.G. Petroclival Meningioma Leading to Trigeminal Neuralgia: A Kawase Approach Application. World Neurosurg. 2021, 151, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, J.D.; Fukushima, T.; Giannotta, S.L. Microanatomical Study of the Extradural Middle Fossa Approach to the Petroclival and Posterior Cavernous Sinus Region. Neurosurgery 1994, 34, 1009–10016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, I.-H.; Yoo, J.; Roh, T.H.; Park, H.H.; Hong, C.-K. Importance of Sufficient Petrosectomy in an Anterior Petrosal Approach: Relightening of the Kawase Pyramid. World Neurosurg. 2021, 153, e11–e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiger, H.-J.; Hänggi, D.; Stummer, W.; Winkler, P.A. Custom-tailored transdural anterior transpetrosal approach to ventral pons and retroclival regions. J. Neurosurg. 2006, 104, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Zhang, L.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Jia, G.; Tang, J.; Meng, G. Surgical resection of large and giant petroclival meningiomas via a modified anterior transpetrous approach. Neurosurg. Rev. 2013, 36, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.; Zhang, X.-H.; Han, D.-H.; Jin, Y.-C. Intradural Transpetrosectomy for Petrous Apex Meningiomas. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc. 2019, 62, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.K.; Salunke, P. Intradural anterior petrosectomy for petroclival meningiomas: A new surgical technique and results in 5 patients. J. Neurosurg. 2012, 117, 1007–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M.; Shastri, S. Single piece fronto-temporo-orbito-zygomatic craniotomy: A personal experience and review of surgical technique. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2018, 32, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mefty, O.; Fox, J.L.; Smith, R.R. Petrosal Approach for Petroclival Meningiomas. Neurosurgery 1988, 22, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almefty, O.; Ayoubi, S.; Smith, R.R. The Petrosal Approach: Indications, Technique, and Results. In Processes of the Cranial Midline; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 1991; Volume 53, pp. 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aum, D.; Rassi, M.S.; Al-Mefty, O. Petroclival meningiomas and the petrosal approach. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 170, pp. 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behari, S.; Tyagi, I.; Banerji, D.; Kumar, V.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Phadke, R.V.; Jain, V.K. Postauricular, transpetrous, presigmoid approach for extensive skull base tumors in the petroclival region: The successes and the travails. Acta Neurochir. 2010, 152, 1633–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junior, J.d.M.; Junior, J.; Nunes, C.; Cabral, G.A.S.; Lapenta, M.; Landeiro, J. Predicting the presigmoid retrolabyrinthine space using a sigmoid sinus tomography classification: A cadaveric study. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2014, 5, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekha, L.N.; Schessel, D.A.; Bucur, S.D.; Raso, J.L.; Wright, D.C. Partial Labyrinthectomy Petrous Apicectomy Approach to Neoplastic and Vascular Lesions of the Petroclival Area. Neurosurgery 1999, 44, 537–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calbucci, F. Treatment Strategy for Sphenopetroclival Meningiomas. World Neurosurg. 2011, 75, 419–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Pérez, R.; Silveira-Bertazzo, G.; Rangel, G.G.; Albiña, P.; Hardesty, D.; Carrau, R.L.; Prevedello, D.M. The historical perspective in approaches to the spheno-petro-clival meningiomas. Neurosurg. Rev. 2019, 44, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Aziz, K.M.; Sanan, A.; van Loveren, H.R.; Tew, J.M.; Keller, J.T.; Pensak, M.L. Petroclival meningiomas: Predictive parameters for transpetrosal approaches. Neurosurgery 2000, 47, 139–150; discussion 150–152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dolenc, V.V. Frontotemporal epidural approach to trigeminal neurinomas. Acta Neurochir. 1994, 130, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meybodi, A.T.; Liu, J.K. Combined Petrosal Approach for Resection of a Large Trigeminal Schwannoma With Meckel’s Cave Involvement—Part II: Microsurgical Approach and Tumor Resection: 2-Dimensional Operative Video. Oper. Neurosurg. 2020, 20, E226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Pérez, R.; Hernández-Álvarez, V.; Maturana, R.; Mura, J.M. The extradural minipterional pretemporal approach for the treatment of spheno-petro-clival meningiomas. Acta Neurochir. 2019, 161, 2577–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couldwell, W.T.; MacDonald, J.D.; Taussky, P. Complete Resection of the Cavernous Sinus—Indications and Technique. World Neurosurg. 2014, 82, 1264–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, C.-H.; Wang, J.-T.; Lin, C.-F.; Chen, S.-C.; Lin, C.-J.; Hsu, S.P.C.; Chen, M.-H. Pretemporal trans–Meckel’s cave transtentorial approach for large petroclival meningiomas. Neurosurg. Focus 2018, 44, E10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Pérez, R.; Tsimpas, A.; Marin-Contreras, F.; Maturana, R.; Hernandez-Alvarez, V.; Labib, M.A.; Poblete, T.; Rubino, P.; Mura, J. The Minimally Invasive Posterolateral Transcavernous-Transtentorial Approach. Technical Nuances, Proof of Feasibility, and Surgical Outcomes Throughout a Case Series of Sphenopetroclival Meningiomas. World Neurosurg. 2021, 155, e564–e575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, J.L.; Sampath, R.; Quattlebaum, S.C.; Casey, M.A.; Folzenlogen, Z.A.; Ramakrishnan, V.R.; Youssef, A.S. Expanding the endoscopic transpterygoid corridor to the petroclival region: Anatomical study and volumetric comparative analysis. J. Neurosurg. 2018, 128, 1855–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquesson, T.; Simon, E.; Berhouma, M.; Jouanneau, E. Anatomic comparison of anterior petrosectomy versus the expanded endoscopic endonasal approach: Interest in petroclival tumors surgery. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2015, 37, 1199–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Notaris, M.; Cavallo, L.M.; Prats-Galino, A.; Esposito, I.; Benet, A.; Poblete, J.; Valente, V.; Gonzalez, J.B.; Ferrer, E.; Cappabianca, P. Endoscopic endonasal transclival approach and retrosigmoid approach to the clival and petroclival regions. Neurosurgery 2009, 65, ons42–ons52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muto, J.; Prevedello, D.M.; Filho, L.F.S.D.; Tang, I.P.; Oyama, K.; Kerr, E.E.; Otto, B.A.; Kawase, T.; Yoshida, K.; Carrau, R.L. Comparative analysis of the anterior transpetrosal approach with the endoscopic endonasal approach to the petroclival region. J. Neurosurg. 2016, 125, 1171–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassam, A.B.; Gardner, P.; Snyderman, C.; Mintz, A.; Carrau, R. Expanded endonasal approach: Fully endoscopic, completely transnasal approach to the middle third of the clivus, petrous bone, middle cranial fossa, and infratemporal fossa. Neurosurg. Focus 2005, 19, E6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassam, A.B.; Mintz, A.H.; Gardner, P.A.; Horowitz, M.B.; Carrau, R.L.; Snyderman, C.H. The Expanded Endonasal Approach for an Endoscopic Transnasal Clipping and Aneurysmorrhaphy of a Large Vertebral Artery Aneurysm: Technical Case Report. Oper. Neurosurg. 2006, 59, ONSE162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Rivera-Serrano, C.M.; Snyderman, C.H.; Gardner, P.; Prevedello, D.; Bs, S.W.; Kassam, A.B.; Carrau, R.L.; Germanwala, A.; Zanation, A. Nasoseptal “Rescue” flap: A novel modification of the nasoseptal flap technique for pituitary surgery. Laryngoscope 2011, 121, 990–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morera, V.A.; Fernandez-Miranda, J.C.; Prevedello, D.M.; Madhok, R.; Barges-Coll, J.; Gardner, P.; Carrau, R.; Snyderman, C.H.; Rhoton, A.L.; Kassam, A.B. “Far-Medial” Expanded Endonasal Approach to the Inferior Third of the Clivus. Neurosurgery 2010, 66, ons211–ons220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadag, A.; Kirgiz, P.G.; Bozkurt, B.; Kucukyuruk, B.; ReFaey, K.; Middlebrooks, E.H.; Senoglu, M.; Tanriover, N. The benefits of inferolateral transtubercular route on intradural surgical exposure using the endoscopic endonasal transclival approach. Acta Neurochir. 2021, 163, 2141–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbero, J.M.R.; Noiphithak, R.; Yanez-Siller, J.C.; Subramaniam, S.; Calha, M.S.; Otto, B.A.; Carrau, R.L.; Prevedello, D.M. Expanded Endoscopic Endonasal Approach to the Inframeatal Area: Anatomic Nuances with Surgical Implications. World Neurosurg. 2018, 120, e1234–e1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Miranda, J.C.; Morera, V.A.; Snyderman, C.H.; Gardner, P. Endoscopic Endonasal Transclival Approach to the Jugular Tubercle. Neurosurgery 2012, 71, ons146–ons159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghei-Razavi, H.; Truong, H.Q.; Cabral, D.T.F.; Sun, X.; Celtikci, E.; Wang, E.; Snyderman, C.; Gardner, P.A.; Fernandez-Miranda, J.C. Endoscopic Endonasal Petrosectomy: Anatomical Investigation, Limitations, and Surgical Relevance. Oper. Neurosurg. 2018, 16, 557–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, J.D.; Marsh, R.; Turner, M.T. Contralateral Transmaxillary Approach for Resection of Chondrosarcoma of the Petrous Apex: A Case Report. Ear Nose Throat J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyderman, C.H.; Gardner, P.A.; Wang, E.W.; Fernandez-Miranda, J.C.; Valappil, B. Experience With the Endoscopic Contralateral Transmaxillary Approach to the Petroclival Skull Base. Laryngoscope 2020, 131, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Gompel, J.J.; Alikhani, P.; Tabor, M.H.; Van Loveren, H.R.; Agazzi, S.; Froelich, S.; Youssef, A.S. Anterior inferior petrosectomy: Defining the role of endonasal endoscopic techniques for petrous apex approaches. J. Neurosurg. 2014, 120, 1321–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassam, A.B.; Prevedello, D.M.; Thomas, A.; Gardner, P.; Mintz, A.; Snyderman, C.; Carrau, R. Endoscopic endonasal pituitary transposition for a transdorsum sellae approach to the interpeduncular cistern. Neurosurgery 2008, 62, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohata, H.; Goto, T.; Nagm, A.; Kannepalli, N.R.; Nakajo, K.; Morisako, H.; Goto, H.; Uda, T.; Kawahara, S.; Ohata, K. Surgical implementation and efficacy of endoscopic endonasal extradural posterior clinoidectomy. J. Neurosurg. 2020, 133, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kano, H.; Park, K.-J.; Kondziolka, D.; Iyer, A.; Liu, X.; Tonetti, D.; Flickinger, J.C.; Lunsford, L.D. Does Prior Microsurgery Improve or Worsen the Outcomes of Stereotactic Radiosurgery for Cavernous Sinus Meningiomas? Neurosurgery 2013, 73, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Miranda, J.C.; Gardner, P.A.; Rastelli, M.M.; Peris-Celda, M.; Koutourousiou, M.; Peace, D.; Snyderman, C.H.; Rhoton, A.L. Endoscopic endonasal transcavernous posterior clinoidectomy with interdural pituitary transposition. J. Neurosurg. 2014, 121, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, H.Q.; Borghei-Razavi, H.; Najera, E.; Nakassa, A.C.I.; Wang, E.W.; Snyderman, C.H.; Gardner, P.A.; Fernandez-Miranda, J.C. Bilateral coagulation of inferior hypophyseal artery and pituitary transposition during endoscopic endonasal interdural posterior clinoidectomy: Do they affect pituitary function? J. Neurosurg. 2019, 131, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.; Kondo, K.; Hanakita, S.; Hasegawa, H.; Yoshino, M.; Teranishi, Y.; Kin, T.; Saito, N. Endoscopic transsphenoidal anterior petrosal approach for locally aggressive tumors involving the internal auditory canal, jugular fossa, and cavernous sinus. J. Neurosurg. 2017, 126, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer-Furlan, A.; Abi-Hachem, R.; Jamshidi, A.O.; Carrau, R.L.; Prevedello, D.M. Endoscopic trans-sphenoidal surgery for petroclival and clival meningiomas. J. Neurosurg. Sci. 2016, 60, 495–502. [Google Scholar]

- Beer-Furlan, A.; Vellutini, E.A.; Balsalobre, L.; Stamm, A.C. Endoscopic Endonasal Approach to Ventral Posterior Fossa Meningiomas. Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 26, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simal-Julian, J.A.; Román-Mena, L.P.D.S.; Sanchis-Martín, M.R.; Quiroz-Tejada, A.; Miranda-Lloret, P.; Botella-Asunción, C. Septal rhinopharyngeal flap: A novel technique for skull base reconstruction after endoscopic endonasal clivectomies. J. Neurosurg. 2021, 136, 1601–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adachi, K.; Hasegawa, M.; Tateyama, S.; Kawazoe, Y.; Hirose, Y. Surgical Strategy for and Anatomic Locations of Petroapex and Petroclival Meningiomas Based on Evaluation of the Feeding Artery. World Neurosurg. 2018, 116, e611–e623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, T.; Zhu, H.; Yan, R.; Yang, J.; Xing, J.; Li, Y. RETRACTED: Ten years of experience with microsurgical treatment of large and giant petroclival meningiomas. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2013, 20, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, A.; Muzumdar, D. Conventional posterior fossa approach for surgery on petroclival meningiomas: A report on an experience with 28 cases. Surg. Neurol. 2004, 62, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomio, R.; Toda, M.; Sutiono, A.B.; Horiguchi, T.; Aiso, S.; Yoshida, K. Grüber’s ligament as a useful landmark for the abducens nerve in the transnasal approach. J. Neurosurg. 2015, 122, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couldwell, W.T.; Fukushima, T.; Giannotta, S.L.; Weiss, M.H. Petroclival meningiomas: Surgical experience in 109 cases. J. Neurosurg. 1996, 84, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, I.-H.; Yoo, J.; Park, H.H.; Hong, C.-K. Differences in surgical outcome between petroclival meningioma and anterior petrous meningioma. Acta Neurochir. 2021, 163, 1697–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, A.; Javalkar, V.; Banerjee, A.D. Petroclival meningiomas: Study on outcomes, complications and recurrence rates. J. Neurosurg. 2011, 114, 1268–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, A.; Kothari, M. Editorial. J. Neurosurg. 2010, 113, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinpeter, G. Invasion of the cavernous sinus by medial sphenoid meningioma—“Radical” surgery and recurrence. Acta Neurochir. 1990, 103, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindou, M.; Nebbal, M.; Guclu, B. Cavernous Sinus Meningiomas: Imaging and Surgical Strategy. Neurosurgery 2014, 42, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fariselli, L.; Biroli, A.; Signorelli, A.; Broggi, M.; Marchetti, M.; Biroli, F. The cavernous sinus meningiomas’ dilemma: Surgery or stereotactic radiosurgery? Rep. Pract. Oncol. Radiother. 2016, 21, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raheja, A.; Couldwell, W.T. Cavernous Sinus Meningioma with Orbital Involvement: Algorithmic Decision-Making and Treatment Strategy. J. Neurol. Surg. Part B Skull Base 2020, 81, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer-Furlan, A.; Priddy, B.H.; Jamshidi, A.O.; Shaikhouni, A.; Prevedello, L.M.; Filho, L.D.; Otto, B.A.; Carrau, R.L.; Prevedello, D.M. Improving Function in Cavernous Sinus Meningiomas: A Modern Treatment Algorithm. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gozal, Y.M.; Alzhrani, G.; Abou-Al-Shaar, H.; Azab, M.A.; Walsh, M.T.; Couldwell, W.T. Outcomes of decompressive surgery for cavernous sinus meningiomas: Long-term follow-up in 50 patients. J. Neurosurg. 2020, 132, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talacchi, A.; Hasanbelliu, A.; D’Amico, A.; Gianas, N.R.; Locatelli, F.; Pasqualin, A.; Longhi, M.; Nicolato, A. Long-term follow-up after surgical removal of meningioma of the inner third of the sphenoidal wing: Outcome determinants and different strategies. Neurosurg. Rev. 2018, 43, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couldwell, W.T.; Kan, P.; Liu, J.K.; Apfelbaum, R.I. Decompression of cavernous sinus meningioma for preservation and improvement of cranial nerve function. J. Neurosurg. 2006, 105, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggert, H.R. Extradural and intradural microsurgical approaches to lesions of the optic canal and the superior orbital fissure. Acta Neurochir. 1985, 74, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesoin, F.; Jomin, M.; Bouchez, B.; Duret, M.; Clarisse, J.; Arnott, G.; Pellerin, P.; Francois, P. Management of cavernous sinus meningiomas. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 1985, 28, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioffi, F.; Bernini, F.; Punzo, A.; Natale, M.; Muras, I. Cavernous sinus meningiomas. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 1987, 30, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mickey, B.; Close, L.; Schaefer, S.; Samson, D. A combined frontotemporal and lateral infratemporal fossa approach to the skull base. J. Neurosurg. 1988, 68, 678–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Mefty, O. Clinoidal meningiomas. J. Neurosurg. 1990, 73, 840–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekhar, L.N.; Pomeranz, S.; Sen, C.N. Management of Tumours Involving the Cavernous Sinus. In Processes of the Cranial Midline; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 1991; Volume 53, pp. 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzino, G.; Hirsch, W.L.; Pomonis, S.; Sen, C.N.; Sekhar, L.N. Cavernous sinus tumors: Neuroradiologic and neurosurgical considerations on 150 operated cases. J. Neurosurg. Sci. 1992, 36, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Demonte, F.; Smith, H.K.; Al-Mefty, O. Outcome of aggressive removal of cavernous sinus meningiomas. J. Neurosurg. 1994, 81, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, P.Y.; Miller, N.R.; Long, D.M. Treatment of Cavernous Sinus Meningiomas. J. Neurosurg. 1995, 82, 702–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhar, L.N.; Patel, S.; Cusimano, M.; Wright, D.C.; Sen, C.N.; Bank, W.O. Surgical Treatment of Meningiomas Involving the Cavernous Sinus: Evolving Ideas Based on a Ten Year Experience. In Modern Neurosurgery of Meningiomas and Pituitary Adenomas; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 1996; pp. 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, M.G.; van Loveren, H.R.; Tew, J.M. The Surgical Resectability of Meningiomas of the Cavernous Sinus. Neurosurgery 1997, 40, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendl, G.; Schröttner, O.; Eustacchio, S.; Ganz, J.; Feichtinger, K. Cavernous sinus meningiomas--what is the strategy: Upfront or adjuvant gamma knife surgery? Ster. Funct. Neurosurg. 1998, 70, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, S.; Hide, T.; Shinojima, N.; Hasegawa, Y.; Kawano, T.; Kuratsu, J.-I. Endoscopic endonasal skull base approach for parasellar lesions: Initial experiences, results, efficacy, and complications. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2014, 5, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, F.H.; Haque, M.R. Microsurgical management of benign lesions interior to the cavernous sinus: A case series. Asian J. Neurosurg. 2017, 12, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Inbar, O.; Tata, A.; Moosa, S.; Lee, C.-C.; Sheehan, J.P. Stereotactic radiosurgery in the treatment of parasellar meningiomas: Long-term volumetric evaluation. J. Neurosurg. 2018, 128, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graillon, T.; Regis, J.; Barlier, A.; Brue, T.; Dufour, H.; Buchfelder, M. Parasellar Meningiomas. Neuroendocrinology 2020, 110, 780–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najera, E.; Muhsen, B.A.; Borghei-Razavi, H.; Adada, B. Cavernous Sinus Meningioma Resection Through Orbitozygomatic Craniotomy. World Neurosurg. 2021, 148, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiegelmann, R.; Cohen, Z.R.; Nissim, O.; Alezra, D.; Pfeffer, R. Cavernous sinus meningiomas: A large LINAC radiosurgery series. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2010, 98, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanda, A.; Thakur, J.D.; Sonig, A.; Missios, S. Microsurgical resectability, outcomes, and tumor control in meningiomas occupying the cavernous sinus. J. Neurosurg. 2016, 125, 378–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, W.L.; Sekhar, L.N.; Lanzino, G.; Pomonis, S.; Sen, C.N. Meningiomas involving the cavernous sinus: Value of imaging for predicting surgical complications. Am. J. Roentgenol. 1993, 160, 1083–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S.; Chotai, S.; Liu, Y. Review of surgical anatomy of the tumors involving cavernous sinus. Asian J. Neurosurg. 2018, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akutsu, H.; Kreutzer, J.; Fahlbusch, R.; Buchfelder, M. Transsphenoidal decompression of the sellar floor for cavernous sinus meningiomas. Neurosurgery 2009, 65, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graillon, T.; Fuentes, S.; Metellus, P.; Adetchessi, T.; Gras, R.; Dufour, H. Limited endoscopic transsphenoidal approach for cavernous sinus biopsy: Illustration of 3 cases and discussion. Neurochirurgie 2014, 60, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, B.; Zhang, X.; Barkhoudarian, G.; Griffiths, C.F.; Kelly, D.F. Endonasal Endoscopic Management of Parasellar and Cavernous Sinus Meningiomas. Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 26, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amelot, A.; Van Effenterre, R.; Kalamarides, M.; Cornu, P.; Boch, A.-L. Natural history of cavernous sinus meningiomas. J. Neurosurg. 2019, 130, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, C.G.; Schnurman, Z.; Ashayeri, K.; Kazi, E.; Mullen, R.; Gurewitz, J.; Golfinos, J.G.; Sen, C.; Placantonakis, D.G.; Pacione, D.; et al. Volumetric growth rates of untreated cavernous sinus meningiomas. J. Neurosurg. 2022, 136, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathiesen, T.; Lindquist, C.; Kihlström, L.; Karlsson, B. Recurrence of Cranial Base Meningiomas. Neurosurgery 1996, 39, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heth, J.A.; Al-Mefty, O. Cavernous sinus meningiomas. Neurosurg. Focus 2003, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolenc, V. Microsurgical removal of large sphenoidal bone meningiomas. Acta Neurochir. Suppl. 1979, 28, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aad, G.; Abbott, B.; Abdallah, J.; Abdelalim, A.A.; Abdesselam, A.; Abdinov, O.; Abi, B.; Abolins, M.; Abramowicz, H.; Abreu, H.; et al. Observation of a Centrality-Dependent Dijet Asymmetry in Lead-Lead Collisions atsNN=2.76 TeVwith the ATLAS Detector at the LHC. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 252303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolenc, V.V. A combined epi- and subdural direct approach to carotid-ophthalmic artery aneurysms. J. Neurosurg. 1985, 62, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolenc, V.V.; Škrap, M.; Šušteršič, J.; Škrbec, M.; Morina, A. A Transcavernous-transsellar Approach to the Basilar Tip Aneurysms. Br. J. Neurosurg. 1987, 1, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolenc, V.V. Surgery of vascular lesions of the cavernous sinus. Clin. Neurosurg. 1990, 36, 240–255. [Google Scholar]

- Dolenc, V.V. Transcranial Epidural Approach to Pituitary Tumors Extending beyond the Sella. Neurosurgery 1997, 41, 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolenc, V.V. A Combined Transorbital-Transclinoid and Transsylvian Approach to Carotid-Ophthalmic Aneurysms without Retraction of the Brain. In Neurosurgical Management of Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Haemorrhage; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 1999; Volume 72, pp. 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolenc, V.V. Extradural Approach to Intracavernous ICA Aneurysms. In Neurosurgical Management of Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Haemorrhage; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 1999; Volume 72, pp. 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ambrosio, A.L.; Mocco, J.; Hankinson, T.C.; Bruce, J.N.; van Loveren, H.R. Quantification of the frontotemporal orbitozygomatic approach using a three-dimensional visualization and modeling appli-cation. Neurosurgery 2008, 62, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knosp, E.; Perneczky, A.; Koos, W.T.; Fries, G.; Matula, C. Meningiomas of the Space of the Cavernous Sinus. Neurosurgery 1996, 38, 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seçkin, H.; Avci, E.; Uluç, K.; Niemann, D.; Başkaya, M.K. The work horse of skull base surgery: Orbitozygomatic approach. Technique, modifications, and applications. Neurosurg. Focus 2008, 25, E4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanriover, N.; Ulm, A.J.; Rhoton, A.L.; Kawashima, M.; Yoshioka, N.; Lewis, S.B. One-Piece Versus Two-Piece Orbitozygomatic Craniotomy:Quantitative And Qualitative Considerations. Oper. Neurosurg. 2006, 58, ONS-229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziz, K.M.A.; Froelich, S.C.; Dagnew, E.; Jean, W.; Breneman, J.C.; Zuccarello, M.; van Loveren, H.R.; Tew, J.M. Large sphenoid wing meningiomas involving the cavernous sinus: Conservative surgical strategies for better functional out-comes. Neurosurgery 2004, 54, 1375–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakuba, A.; Tanaka, K.; Suzuki, T.; Nishimura, S. A combined orbitozygomatic infratemporal epidural and subdural approach for lesions involving the entire cavernous sinus. J. Neurosurg. 1989, 71, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-C.; Lin, C.-F.; Liao, C.-H.; Quilis-Quesada, V.; Wang, J.-T.; Wang, W.-H.; Hsu, S.P.C. The pretemporal trans-cavernous trans-Meckel’s trans-tentorial trans-petrosal approach: A combo skill in treating skull base meningiomas. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2020, 146, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morisako, H.; Goto, T.; Ohata, H.; Goudihalli, S.R.; Shirosaka, K.; Ohata, K. Safe maximal resection of primary cavernous sinus meningiomas via a minimal anterior and posterior combined transpetrosal approach. Neurosurg. Focus 2018, 44, E11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sughrue, M.E.; Rutkowski, M.J.; Aranda, D.; Barani, I.J.; McDermott, M.W.; Parsa, A.T. Factors affecting outcome following treatment of patients with cavernous sinus meningiomas. J. Neurosurg. 2010, 113, 1087–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufour, H.; Muracciole, X.; Métellus, P.; Régis, J.; Chinot, O.; Grisoli, F. Long-term Tumor Control and Functional Outcome in Patients with Cavernous Sinus Meningiomas Treated by Radiotherapy with or without Previous Surgery: Is There an Alternative to Aggressive Tumor Removal? Neurosurgery 2001, 48, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, M.; Wydh, E.; Vighetto, A.; Sindou, M. Visual outcome after surgery for cavernous sinus meningioma. Acta Neurochir. 2008, 150, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, J.H.; Norris, J.S.; Akinwunmi, J.; Malhotra, R. Optic Canal Decompression With Dural Sheath Release; A Combined Orbito-Cranial Approach To Preserving Sight From Tumours Invading The Optic Canal. Orbit 2011, 31, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najera, E.; Ibrahim, B.; Muhsen, B.A.; Ali, A.; Sanchez, C.; Obrzut, M.; Borghei-Razavi, H.; Adada, B. Blood Supply of Cranial Nerves Passing Through the Cavernous Sinus: An Anatomical Study and Its Implications for Microsurgical and Endoscopic Cavernous Sinus Surgery. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 4413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavallo, L.M.; Cappabianca, P.; Galzio, R.; Iaconetta, G.; de Divitiis, E.; Tschabitscher, M. Endoscopic Transnasal Approach to the Cavernous Sinus versus Transcranial Route: Anatomic Study. Oper. Neurosurg. 2005, 56, ONS-379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfieri, A.; Jho, H.-D. Endoscopic Endonasal Approaches to the Cavernous Sinus: Surgical Approaches. Neurosurgery 2001, 49, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfieri, A.; Jho, H.D. Endoscopic endonasal cavernous sinus surgery: An anatomic study. Neurosurgery 2001, 48, 827–836. [Google Scholar]

- Rhoton, A.L.; Hardy, D.G.; Chambers, S.M. Microsurgical anatomy and dissection of the sphenoid bone, cavernous sinus and sellar region. Surg. Neurol. 1979, 12, 63–104. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, G.; Pasquini, E. Endoscopic Endonasal Cavernous Sinus Surgery, with Special Reference to Pituitary Adenomas. Front. Horm. Res. 2006, 34, 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappabianca, P.; de Divitiis, E.; Tschabitscher, M. Atlas of Endoscopic Anatomy for Endonasal Intracranial Surgery; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 6 December 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, G.; Calbucci, F. Endoscopic approach to the cavernous sinus via an ethmoido-pterygo-sphenoidal route. In Proceedings of the 5th European Skull Base Society Congress, Copenhagen, Denmark, 15–17 June 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda, A.; Campero, A.; Martins, C.; Rhoton, A.L.; Ribas, G.C. The Medial Wall of the Cavernous Sinus: Microsurgical Anatomy. Neurosurgery 2004, 55, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietemann, J.L.; Kehrli, P.; Maillot, C.; Diniz, R.; Reis, M., Jr.; Neugroschl, C.; Vinclair, L. Is there a dural wall between the cavernous sinus and the pituitary fossa? Anatomical and MRI findings. Neuroradiology 1998, 40, 627–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, W.; Barkhoudarian, G.; Lobo, B.M.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, F.; Eisenberg, A.; Kesari, S.; Krauss, H.; Cohan, P.; Griffiths, C.; et al. Strategy and Technique of Endonasal Endoscopic Bony Decompression and Selective Tumor Removal in Symptomatic Skull Base Meningiomas of the Cavernous Sinus and Meckel’s Cave. World Neurosurg. 2019, 131, e12–e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Guo, H.; Yan, B.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, H.; Sahyouni, R.; Kuan, E.C. Direct Transcavernous Sinus Approach for Endoscopic Endonasal Resection of Intracavernous Sinus Tumors. World Neurosurg. 2019, 128, e478–e487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Wesseling, P.; Brat, D.J.; Cree, I.A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Hawkins, C.; Ng, H.K.; Pfister, S.M.; Reifenberger, G.; et al. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: A summary. Neuro-Oncology 2021, 23, 1231–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen-Gadol, A.A.; Laws, E.R.; Spencer, D.D.; De Salles, A.A.F. The evolution of Harvey Cushing’s surgical approach to pituitary tumors from transsphenoidal to transfrontal. J. Neurosurg. 2005, 103, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.K.; Cohen-Gadol, A.; Laws, E.R.; Cole, C.D.; Kan, P.; Couldwell, W.T. Harvey Cushing and Oskar Hirsch: Early forefathers of modern transsphenoidal surgery. J. Neurosurg. 2005, 103, 1096–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.J.; Zaidi, H.A.; Laws, E.D. History of endonasal skull base surgery. J. Neurosurg. Sci. 2016, 60, 441–453. [Google Scholar]

- Welbourn, R.B. The evolution of transsphenoidal pituitary microsurgery. Surgery 1986, 100, 1185–1190. [Google Scholar]

- Cappabianca, P.; de Divitiis, E. Endoscopy and Transsphenoidal Surgery. Neurosurgery 2004, 54, 1043–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.K.; Das, K.; Weiss, M.H.; Laws, E.R.; Couldwell, W.T. The history and evolution of transsphenoidal surgery. J. Neurosurg. 2001, 95, 1083–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiot, G. Transsphenoidal approach in surgical treatment of pituitary adenomas: General principles and indications in non-functioning adenomas. In Diagnosis and Treatment of Pituitary Adenomas; Kohler, P.O., Ross, G.T., Eds.; Excerpta Medica: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1973; pp. 159–178. [Google Scholar]

- Krisht, K.M.; Sorour, M.; Cote, M.; Hardy, J.; Couldwell, W.T. Marching beyond the sella: Gerard Guiot and his contributions to neurosurgery. J. Neurosurg. 2015, 122, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laws, E.R.; Dunn, I.F. The evolution of surgeryethe soul of neurosurgery. In Meningiomas of the Skull Base; Thieme: Stuttgart, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Koutourousiou, M.; Fernandez-Miranda, J.C.; Stefko, S.T.; Wang, E.; Snyderman, C.H.; Gardner, P.A. Endoscopic endonasal surgery for suprasellar meningiomas: Experience with 75 patients. J. Neurosurg. 2014, 120, 1326–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, R.S.; Patel, S.K.; Husain, Q.; Dahodwala, M.Q.; Eloy, J.A.; Liu, J.K. From above or below: The controversy and historical evolution of tuberculum sellae meningioma resection from open to endoscopic skull base approaches. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2014, 21, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavallo, L.M.; Cappabianca, P. Craniopharyngiomas: Infradiaphragmatic and Supradiaphragmatic Type and Their Management in Modern Times. World Neurosurg. 2014, 81, 683–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavallo, L.M.; Frank, G.; Cappabianca, P.; Solari, D.; Mazzatenta, D.; Villa, A.; Zoli, M.; D’Enza, A.I.; Esposito, F.; Pasquini, E. The endoscopic endonasal approach for the management of craniopharyngiomas: A series of 103 patients. J. Neurosurg. 2014, 121, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juraschka, K.; Khan, O.H.; Godoy, B.L.; Monsalves, E.; Kilian, A.; Krischek, B.; Ghare, A.; Vescan, A.; Gentili, F.; Zadeh, G. Endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal approach to large and giant pituitary adenomas: Institutional experience and predictors of extent of resection. J. Neurosurg. 2014, 121, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeswani, S.; Nuño, M.; Wu, A.; Bonert, V.; Carmichael, J.D.; Black, K.L.; Chu, R.; King, W.; Mamelak, A.N. Comparative analysis of outcomes following craniotomy and expanded endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal resection of craniopharyngioma and related tumors: A single-institution study. J. Neurosurg. 2016, 124, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhandapani, S.; Singh, H.; Negm, H.M.; Cohen, S.; Souweidane, M.M.; Greenfield, J.P.; Anand, V.K.; Schwartz, T.H. Endonasal endoscopic reoperation for residual or recurrent craniopharyngiomas. J. Neurosurg. 2017, 126, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussazadeh, N.; Prabhu, V.; Bander, E.D.; Cusic, R.C.; Tsiouris, A.J.; Anand, V.K.; Schwartz, T.H. Endoscopic endonasal versus open transcranial resection of craniopharyngiomas: A case-matched single-institution analysis. Neurosurg. Focus 2016, 41, E7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anakwenze, C.P.; McGovern, S.; Taku, N.; Liao, K.; Boyce-Fappiano, D.R.; Kamiya-Matsuoka, C.; Ghia, A.; Chung, C.; Trifiletti, D.; Ferguson, S.D.; et al. Association Between Facility Volume and Overall Survival for Patients with Grade II Meningioma after Gross Total Resection. World Neurosurg. 2020, 141, e133–e144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magill, S.T.; Young, J.S.; Chae, R.; Aghi, M.K.; Theodosopoulos, P.V.; McDermott, M.W. Relationship between tumor location, size, and WHO grade in meningioma. Neurosurg. Focus 2018, 44, E4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunevicius, A.; Ahn, J.; Fribance, S.; Peker, S.; Hergunsel, B.; Sheehan, D.; Sheehan, K.; Nabeel, A.M.; Reda, W.A.; Tawadros, S.R.; et al. Stereotactic Radiosurgery for Olfactory Groove Meningiomas: An International, Multicenter Study. Neurosurgery 2021, 89, 784–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboukais, R.; Zairi, F.; Lejeune, J.P.; Le Rhun, E.; Vermandel, M.; Blond, S.; Devos, P.; Reyns, N. Grade 2 meningioma and radiosurgery. J. Neurosurg. 2015, 122, 1157–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardesty, D.A.; Wolf, A.B.; Brachman, D.G.; McBride, H.L.; Youssef, E.; Nakaji, P.; Porter, R.W.; Smith, K.A.; Spetzler, R.F.; Sanai, N. The impact of adjuvant stereotactic radiosurgery on atypical meningioma recurrence following aggressive micro-surgical resection. J. Neurosurg. 2013, 119, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Anterior Routes |

|

| Anterolateral Routes |

|

| Lateral Routes |

|

| Posterolateral Routes |

|

| Ventral Approach |

|

| Corridor | Pros | Cons |

| Anterior Route | ||

| Bilateral subfrontal approach |

|

|

| Unilateral subfrontal approach |

|

|

| Transbasal approach |

|

|

| Anterolateral Route | ||

| Pterional approach and its variants |

|

|

| Ventral Route | ||

| Endonasal transethmoidal transcribiform approach |

|

|

| Corridor | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior Route | ||

| Bilateral subfrontal approach |

|

|

| Unilateral subfrontal approach |

| |

| Anterior interhemispheric approach |

|

|

| Anterolateral Route | ||

| Pterional approach and its variants |

|

|

| Ventral Route | ||

| Endonasal transplanum-transtuberculum approach |

| |

| Corridor | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Lateral Route | ||

| Anterior petrosectomy |

|

|

| Posterior petrosectomy |

|

|

| Combined transpetrosal |

| - |

| Posterolateral Route | ||

| Retrosigmoid approach and its variant |

|

|

| Anterolateral Route | ||

| Pretemporal trancavernous anterior transpetrosal approach Extended pterional transtentorial approach |

|

|

| Ventral Route | ||

| Endonasal transclival transpterygoid approach |

|

|

| Corridor | Pros | Cons |

| Lateral Route | ||

| Anterior petrosectomy |

|

|

| Posterior petrosectomy |

|

|

| Combined transpetrosal |

| - |

| Anterolateral Route | ||

| Extended pterional + extradural anterior clinoidectomy |

|

|

| Fronto-temporo-orbito-zygomatic approach + extradural anterior clinoidectomy |

|

|

| Pretemporal trans-cavernous trans-Meckel’s trans-tentorial trans-petrosal |

| - |

| Ventral Route | ||

| Extended endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal Endonasal transethmoidal/transsphenoidal (far lateral) Contralateral endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal approach |

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mastantuoni, C.; Cavallo, L.M.; Esposito, F.; d’Avella, E.; de Divitiis, O.; Somma, T.; Bocchino, A.; Fabozzi, G.L.; Cappabianca, P.; Solari, D. Midline Skull Base Meningiomas: Transcranial and Endonasal Perspectives. Cancers 2022, 14, 2878. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14122878

Mastantuoni C, Cavallo LM, Esposito F, d’Avella E, de Divitiis O, Somma T, Bocchino A, Fabozzi GL, Cappabianca P, Solari D. Midline Skull Base Meningiomas: Transcranial and Endonasal Perspectives. Cancers. 2022; 14(12):2878. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14122878

Chicago/Turabian StyleMastantuoni, Ciro, Luigi Maria Cavallo, Felice Esposito, Elena d’Avella, Oreste de Divitiis, Teresa Somma, Andrea Bocchino, Gianluca Lorenzo Fabozzi, Paolo Cappabianca, and Domenico Solari. 2022. "Midline Skull Base Meningiomas: Transcranial and Endonasal Perspectives" Cancers 14, no. 12: 2878. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14122878

APA StyleMastantuoni, C., Cavallo, L. M., Esposito, F., d’Avella, E., de Divitiis, O., Somma, T., Bocchino, A., Fabozzi, G. L., Cappabianca, P., & Solari, D. (2022). Midline Skull Base Meningiomas: Transcranial and Endonasal Perspectives. Cancers, 14(12), 2878. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14122878