APC Mutations Are Not Confined to Hotspot Regions in Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

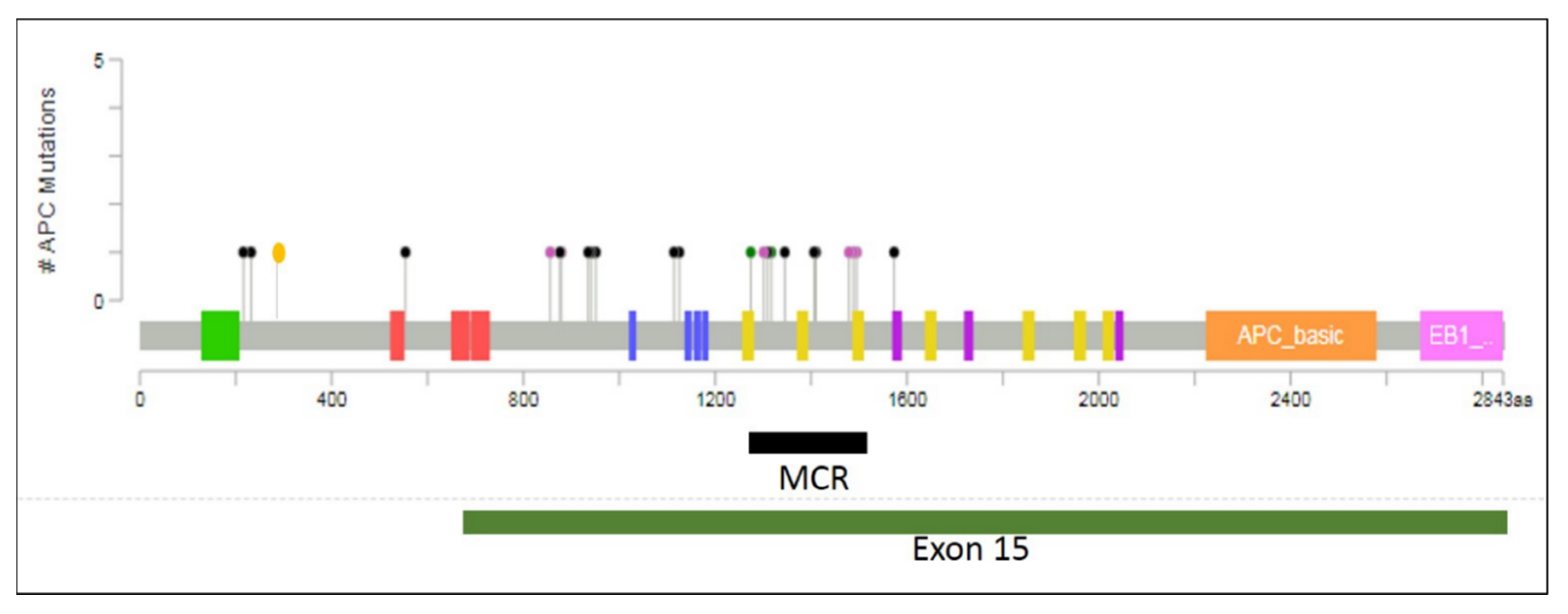

3. Distribution of APC Mutations

4. Microsatellite Instability

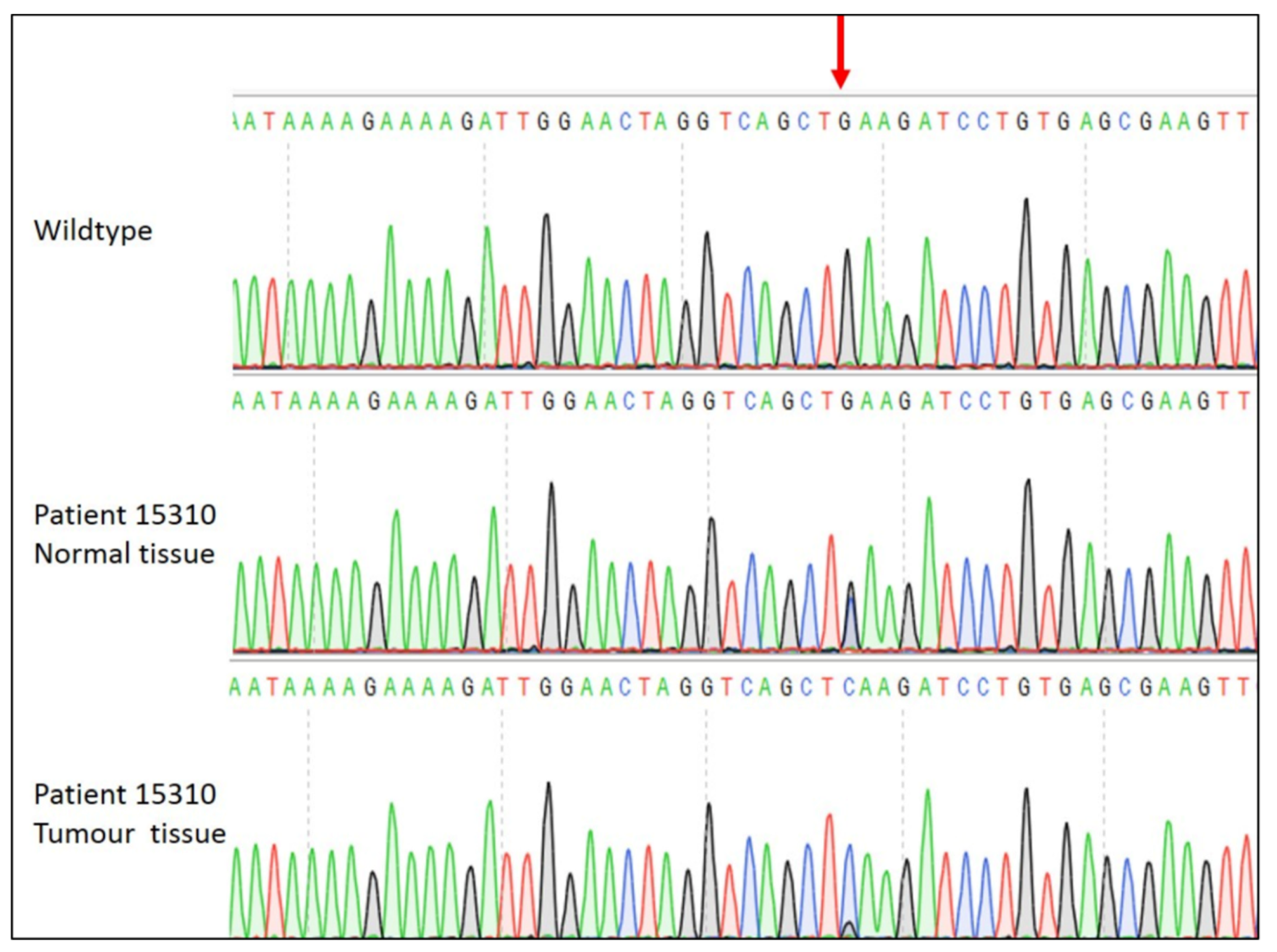

5. Loss of Heterozygosity is Associated with APC Mutation Near Codon 1300

6. Methylation of the APC Promoter

7. Discussion

8. Methods

8.1. Cohort

8.2. DNA Extraction

8.3. Sequencing Library Preparation

8.4. Sequence Analysis and Annotation

8.5. LOH at APC Locus

Sanger Sequencing

8.6. Microsatellite Instability

8.7. Bisulphite Treatment and Methylation Analysis

9. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Dikshit, R.; Eser, S.; Mathers, C.; Rebelo, M.; Parkin, D.M.; Forman, D.; Bray, F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 136, E359–E386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, J.; Xin, L.; Ma, Y.F.; Hu, L.H.; Li, Z.S. Colonoscopy Reduces Colorectal Cancer Incidence and Mortality in Patients with Non-Malignant Findings: A Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 111, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bailey, C.E.; Hu, C.Y.; You, Y.N.; Bednarski, B.K.; Rodriguez-Bigas, M.A.; Skibber, J.M.; Cantor, S.B.; Chang, G.J. Increasing disparities in the age-related incidences of colon and rectal cancers in the United States, 1975–010. JAMA Surg. 2015, 150, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hessami Arani, S.; Kerachian, M.A. Rising rates of colorectal cancer among younger Iranians: Is diet to blame? Curr. Oncol. 2017, 24, e131–e137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, H.T.; Lanspa, S.; Smyrk, T.; Boman, B.; Watson, P.; Lynch, J. Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndromes I & II). Genetics, pathology, natural history, and cancer control, Part I. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 1991, 53, 143–160. [Google Scholar]

- Groden, J.; Thliveris, A.; Samowitz, W.; Carlson, M.; Gelbert, L.; Albertsen, H.; Joslyn, G.; Stevens, J.; Spirio, L.; Robertson, M.; et al. Identification and characterization of the familial adenomatous polyposis coli gene. Cell 1991, 66, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearon, E.R. Molecular genetics of colorectal cancer. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2011, 6, 479–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasry, A.; Zinger, A.; Ben-Neriah, Y. Inflammatory networks underlying colorectal cancer. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, L.C.; Mota, J.M.; Braghiroli, M.I.; Hoff, P.M. The Rising Incidence of Younger Patients with Colorectal Cancer: Questions About Screening, Biology, and Treatment. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2017, 18, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirzin, S.; Marisa, L.; Guimbaud, R.; De Reynies, A.; Legrain, M.; Laurent-Puig, P.; Cordelier, P.; Pradère, B.; Bonnet, D.; Meggetto, F.; et al. Sporadic early-onset colorectal cancer is a specific sub-type of cancer: A morphological, molecular and genetics study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e103159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kinzler, K.W.; Vogelstein, B. Lessons from hereditary colorectal cancer. Cell 1996, 87, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Polakis, P. The many ways of Wnt in cancer. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2007, 17, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boman, B.M.; Fields, J.Z. An APC: WNT Counter-Current-Like Mechanism Regulates Cell Division Along the Human Colonic Crypt Axis: A Mechanism That Explains How APC Mutations Induce Proliferative Abnormalities That Drive Colon Cancer Development. Front. Oncol. 2013, 3, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Munemitsu, S.; Souza, B.; Muller, O.; Albert, I.; Rubinfeld, B.; Polakis, P. The APC gene product associates with microtubules in vivo and promotes their assembly in vitro. Cancer Res. 1994, 54, 3676–3681. [Google Scholar]

- Bellis, J.; Duluc, I.; Romagnolo, B.; Perret, C.; Faux, M.C.; Dujardin, D.; Formstone, C.; Lightowler, S.; Ramsay, R.G.; Freund, J.N.; et al. The tumor suppressor Apc controls planar cell polarities central to gut homeostasis. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 198, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cristofaro, M.; Contursi, A.; D’Amore, S.; Martelli, N.; Spaziante, A.F.; Moschetta, A.; Villani, G. Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC)-induced apoptosis of HT29 colorectal cancer cells depends on mitochondrial oxidative metabolism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1852, 1719–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lamlum, H.; Ilyas, M.; Rowan, A.; Clark, S.; Johnson, V.; Bell, J.; Frayling, I.; Efstathiou, J.; Pack, K.; Payne, S.; et al. The type of somatic mutation at APC in familial adenomatous polyposis is determined by the site of the germline mutation: A new facet to Knudson’s ‘two-hit’ hypothesis. Nat. Med. 1999, 5, 1071–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flood, D.M.; Weiss, N.S.; Cook, L.S.; Emerson, J.C.; Schwartz, S.M.; Potter, J.D. Colorectal cancer incidence in Asian migrants to the United States and their descendants. Cancer Causes Control 2000, 11, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Grimm, S.A.; Chrysovergis, K.; Kosak, J.; Wang, X.; Du, Y.; Burkholder, A.; Janardhan, K.; Mav, D.; Shah, R.; et al. Obesity, rather than diet, drives epigenomic alterations in colonic epithelium resembling cancer progression. Cell Metab. 2014, 19, 702–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kothari, N.; Teer, J.K.; Abbott, A.M.; Srikumar, T.; Zhang, Y.; Yoder, S.J.; Brohl, A.S.; Kim, R.D.; Reed, D.R.; Shibata, D. Increased incidence of FBXW7 and POLE proofreading domain mutations in young adult colorectal cancers. Cancer 2016, 122, 2828–2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Willauer, A.N.; Liu, Y.; Pereira, A.A.; Lam, M.; Morris, J.S.; Raghav, K.P.; Morris, V.K.; Menter, D.; Broaddus, R.; Meric-Bernstam, F.; et al. Clinical and molecular characterization of early-onset colorectal cancer. Cancer 2019, 125, 2002–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perea, J.; Rueda, D.; Canal, A.; Rodríguez, Y.; Álvaro, E.; Osorio, I.; Alegre, C.; Rivera, B.; Martínez, J.; Benítez, J.; et al. Age at onset should be a major criterion for subclassification of colorectal cancer. J. Mol. Diagn. 2014, 16, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raman, R.; Kotapalli, V.; Adduri, R.; Gowrishankar, S.; Bashyam, L.; Chaudhary, A.; Vamsy, M.; Patnaik, S.; Srinivasulu, M.; Sastry, R.; et al. Evidence for possible non-canonical pathway(s) driven early-onset colorectal cancer in India. Mol. Carcinog. 2014, 53 (Suppl. 1), E181–E186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bettington, M.; Walker, N.; Clouston, A.; Brown, I.; Leggett, B.; Whitehall, V. The serrated pathway to colorectal carcinoma: Current concepts and challenges. Histopathology 2013, 62, 367–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Palma, F.D.E.; D’Argenio, V.; Pol, J.; Kroemer, G.; Maiuri, M.C.; Salvatore, F. The Molecular Hallmarks of the Serrated Pathway in Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mori, Y.; Nagse, H.; Ando, H.; Horii, A.; Ichii, S.; Nakatsuru, S.; Aoki, T.; Miki, Y.; Mori, T.; Nakamura, Y. Somatic mutations of the APC gene in colorectal tumors: Mutation cluster region in the APC gene. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1992, 1, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lüchtenborg, M.; Weijenberg, M.P.; Roemen, G.M.; de Bruïne, A.P.; van den Brandt, P.A.; Lentjes, M.H.; Brink, M.; van Engeland, M.; Goldbohm, R.A.; de Goeij, A.F. APC mutations in sporadic colorectal carcinomas from The Netherlands Cohort Study. Carcinogenesis 2004, 25, 1219–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Poncin, J.; Mulkens, J.; Arends, J.W.; de Goeij, A. Optimizing the APC gene mutation analysis in archival colorectal tumor tissue. Diagn. Mol. Pathol. 1999, 8, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.-M.; Qian, J.-C.; Cai, Z.; Tang, T.; Wang, P.; Zhang, K.-H.; Deng, Z.-L.; Cai, J.-P. DNA alterations of microsatellite DNA, p53, APC and K-ras in Chinese colorectal cancer patients. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 42, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmaksoud-Damak, R.; Miladi-Abdennadher, I.; Triki, M.; Khabir, A.; Charfi, S.; Ayadi, L.; Frikha, M.; Sellami-Boudawara, T.; Mokdad-Gargouri, R. Expression and mutation pattern of beta-catenin and adenomatous polyposis coli in colorectal cancer patients. Arch. Med. Res. 2015, 46, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteller, M.; Sparks, A.; Toyota, M.; Sanchez-Cespedes, M.; Capella, G.; Peinado, M.A.; Gonzalez, S.; Tarafa, G.; Sidransky, D.; Meltzer, S.J.; et al. Analysis of adenomatous polyposis coli promoter hypermethylation in human cancer. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 4366–4371. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Powell, S.M.; Zilz, N.; Beazer-Barclay, Y.; Bryan, T.M.; Hamilton, S.R.; Thibodeau, S.N.; Vogelstein, B.; Kinzler, K.W. APC mutations occur early during colorectal tumorigenesis. Nature 1992, 359, 235–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fostira, F.; Yannoukakos, D. A distinct mutation on the alternative splice site of APC exon 9 results in attenuated familial adenomatous polyposis phenotype. Fam. Cancer 2010, 9, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedl, W.; Aretz, S. Familial adenomatous polyposis: Experience from a study of 1164 unrelated german polyposis patients. Hered. Cancer Clin. Pract. 2005, 3, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Simbolo, M.; Mafficini, A.; Agostini, M.; Pedrazzani, C.; Bedin, C.; Urso, E.D.; Nitti, N.; Turri, G.; Scardoni, M.; Fassan, M.; et al. Next-generation sequencing for genetic testing of familial colorectal cancer syndromes. Hered. Cancer Clin. Pract. 2015, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gómez-Fernández, N.; Castellví-Bel, S.; Fernández-Rozadilla, C.; Balaguer, F.; Muñoz, J.; Madrigal, I.; Milà, M.; Graña, B.; Vega, A.; Castells, A.; et al. Molecular analysis of the APC and MUTYH genes in Galician and Catalonian FAP families: A different spectrum of mutations? BMC Med. Genet. 2009, 10, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miyaki, M.; Konishi, M.; Kikuchi-Yanoshita, R.; Enomoto, M.; Igari, T.; Tanaka, K.; Muraoka, M.; Takahashi, H.; Amada, Y.; Fukayama, M. Characteristics of somatic mutation of the adenomatous polyposis coli gene in colorectal tumors. Cancer Res. 1994, 54, 3011–3020. [Google Scholar]

- Lagarde, A.; Rouleau, E.; Ferrari, A.; Noguchi, T.; Qiu, J.; Briaux, A.; Bourdon, V.; Remy, V.; Gaildrat, P.; Adélaïde, J.; et al. Germline APC mutation spectrum derived from 863 genomic variations identified through a 15-year medical genetics service to French patients with FAP. J. Med. Genet. 2010, 47, 721–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- White, S.; Bubb, V.J.; Wyllie, A.H. Germline APC mutation (Gln1317) in a cancer-prone family that does not result in familial adenomatous polyposis. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 1996, 15, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceto, G.; Curia, M.C.; Veschi, S.; De Lellis, L.; Mammarella, S.; Catalano, T.; Stuppia, L.; Palka, G.; Valanzano, R.; Tonelli, F.; et al. Mutations of APC and MYH in unrelated Italian patients with adenomatous polyposis coli. Hum. Mutat. 2005, 26, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.-F.; Liu, Z.; Yan, P.; Shao, X.; Deng, X.; Sam, C.; Chen, Y.-G.; Xu, Y.-P.; Wang, X.; Wang, G.-Y.; et al. Identification of a novel mutation associated with familial adenomatous polyposis and colorectal cancer. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2015, 36, 1049–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ishida, H.; Yamaguchi, T.; Chiba, K.; Iijima, T.; Horiguchi, S.I. A case report of ascending colon adenosquamous carcinoma with BRAF V600E mutation. Int. Cancer Conf. J. 2017, 6, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowan, A.J.; Lamlum, H.; Ilyas, M.; Wheeler, J.; Straub, J.; Papadopoulou, A.; Bicknell, D.; Bodmer, W.F.; Tomlinson, I.P.M. APC mutations in sporadic colorectal tumors: A mutational “hotspot” and interdependence of the “two hits”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 3352–3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, B.Q.; Liu, P.P.; Zhang, C.H. Correlation between the methylation of APC gene promoter and colon cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 14, 2315–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fearnhead, N.S.; Britton, M.P.; Bodmer, W.F. The ABC of APC. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001, 10, 721–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leoz, M.L.; Carballal, S.; Moreira, L.; Ocana, T.; Balaguer, F. The genetic basis of familial adenomatous polyposis and its implications for clinical practice and risk management. Appl. Clin. Genet. 2015, 8, 95–107. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, S.H.; Wacker, I.; Appelt, U.K.; Behrens, J.; Schneikert, J. A common role for various human truncated adenomatous polyposis coli isoforms in the control of beta-catenin activity and cell proliferation. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Christie, M.; Jorissen, R.N.; Mouradov, D.; Sakthianandeswaren, A.; Li, S.; Day, F.; Tsui, C.; Lipton, L.; Desai, J.; Jones, I.T.; et al. Different APC genotypes in proximal and distal sporadic colorectal cancers suggest distinct WNT/beta-catenin signalling thresholds for tumourigenesis. Oncogene 2013, 32, 4675–4682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohler, E.M.; Derungs, A.; Daum, G.; Behrens, J.; Schneikert, J. Functional definition of the mutation cluster region of adenomatous polyposis coli in colorectal tumours. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008, 17, 1978–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bufill, J.A. Colorectal cancer: Evidence for distinct genetic categories based on proximal or distal tumor location. Ann. Intern. Med. 1990, 113, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.M.; Marcet, J.E.; Frattini, J.C.; Prather, A.D.; Mateka, J.J.; Nfonsam, V.N. Is it time to lower the recommended screening age for colorectal cancer? J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2011, 213, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perea, J.; Cano, J.M.; Rueda, D.; García, J.L.; Inglada, L.; Osorio, I.; Arriba, M.; Pérez, J.; Gaspar, M.; Fernández-Miguel, T.; et al. Classifying early-onset colorectal cancer according to tumor location: New potential subcategories to explore. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2015, 5, 2308–2313. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ballester, V.; Rashtak, S.; Boardman, L. Clinical and molecular features of young-onset colorectal cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 1736–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salovaara, R.; Loukola, A.; Kristo, P.; Kääriäinen, H.; Ahtola, H.; Eskelinen, M.; Härkönen, N.; Julkunen, R.; Kangas, E.; Ojala, S.; et al. Population-based molecular detection of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000, 18, 2193–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, W.K.; To, K.-F.; Man, E.P.S.; Chan, M.W.Y.; Hui, A.J.; Ng, S.S.M.; Lau, J.Y.W.; Sung, J.J.Y. Detection of hypermethylated DNA or cyclooxygenase-2 messenger RNA in fecal samples of patients with colorectal cancer or polyps. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 102, 1070–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nystrom, M.; Mutanen, M. Diet and epigenetics in colon cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 15, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakkaart, C.; Ellison-Loschmann, L.; Day, R.; Sporle, A.; Koea, J.; Harawira, P.; Cheng, S.; Gray, M.; Whaanga, T.; Pearce, N.; et al. Germline CDH1 mutations are a significant contributor to the high frequency of early-onset diffuse gastric cancer cases in New Zealand Maori. Fam. Cancer. 2019, 18, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McKenna, A.; Hanna, M.; Banks, E.; Sivachenko, A.; Cibulskis, K.; Kernytsky, A.; Garimella, K.; Altshuler, D.; Gabriel, S.B.; Daly, M.J.; et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: A MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 1297–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cingolani, P.; Platts, A.; Wang, L.L.; Coon, M.; Nguyen, T.; Wang, L.; Land, S.J.; Lu, X.; Ruden, D.M. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118, iso-2; iso-3. Fly 2012, 6, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Robinson, J.T.; Thorvaldsdóttir, H.; Winckler, W.; Guttman, M.; Lander, E.S.; Getz, G.; Mesirov, J.P. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 24–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kumar, P.; Henikoff, S.; Ng, P.C. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.; Sims, G.E.; Murphy, S.; Miller, J.R.; Chan, A.P. Predicting the functional effect of amino acid substitutions and indels. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e46688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reva, B.; Antipin, Y.; Sander, C. Predicting the functional impact of protein mutations: Application to cancer genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, e118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adzhubei, I.; Jordan, D.M.; Sunyaev, S.R. Predicting functional effect of human missense mutations using PolyPhen-2. Curr. Protoc. Hum. Genet. 2013, 76, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- South, C.D.; Yearsley, M.; Martin, E.; Arnold, M.; Frankel, W.; Hampel, H. Immunohistochemistry staining for the mismatch repair proteins in the clinical care of patients with colorectal cancer. Genet. Med. 2009, 11, 812–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Number | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 25 | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 11 | 44 |

| Female | 14 | 56 |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | ||

| <30 | 1 | 4 |

| 31–40 | 6 | 24 |

| 41–50 | 18 | 72 |

| Tumour site | ||

| Caecum | 1 | 4 |

| Ascending colon | 6 | 24 |

| Hepatic flexure | 1 | 4 |

| Splenic flexure | 1 | 4 |

| Descending colon | 3 | 12 |

| Sigmoid colon | 12 | 48 |

| Rectosigmoid | 1 | 4 |

| Pathology | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 23 | 92 |

| Adenosquamous carcinoma | 1 | 4 |

| Signet-ring cell carcinoma | 1 | 4 |

| Patient Number | Microsatellite Instability | Mutation | Mutational Outcome | Mutational Assessment 1 | APC Methylation | LOH | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA | rsID | Protein | |||||||

| 10006 | MSI | c.2626C>T | rs121913333 | p.R876X | Nonsense | Damaging | U | - | [32] |

| 10765 | MSS | c.835-8A>G | rs1064793022 | Splice variant | Truncation 2 | Damaging | U | - | [33] |

| 12294 | MSS | c.1660C>T | rs137854573 | p.R554X | Nonsense | Damaging | M | - | [34] |

| 12961 | MSS | c.2853T>G | rs575406600 | p.Y951X | Nonsense | Damaging | M | - | [34] |

| 13046 | MSS | c.4488delT | n/a | p.P1497fsX | Frameshift | Damaging | U | - | This Study |

| c.2805C>A | rs137854575 | p.Y935X | Nonsense | Damaging | [35] | ||||

| 13501 | MSS | c.2636delA | n/a | p.Q879fsX | Frameshift | Damaging | U | - | This Study |

| 13564 | MSS | c.4033G>T | rs1211642532 | P.E1345X | Nonsense | Damaging | U | LOH | [36] |

| 14459 | MSS | c.4463delT | rs1114167577 | p.L1488fsX | Frameshift | Damaging | M | - | [37] |

| c.3826delT | n/a | p.S1276fsX | Frameshift | Damaging | This Study | ||||

| 15052 | MSS | - | - | - | - | - | M | - | - |

| 15296 | MSS | - | - | - | - | - | U | - | - |

| 15310 | MSS | c.4216C>T | rs587782518 | p.Q1406X | Nonsense | Damaging | U | LOH | [38] |

| c.3949G>C | rs1801166 | p.E1317Q | Missense | Benign | [39] | ||||

| 15471 | MSS | - | - | - | - | - | M | - | - |

| 16872 | MSS | - | - | - | - | - | U | - | - |

| 16993 | MSS | c.4717G>T | rs878853217 | p.E1573X | Nonsense | Damaging | U | - | [40] |

| c.2821G>T | n/a | p.E941X | Nonsense | Damaging | [37] | ||||

| 17068 | MSS | - | - | - | - | - | M | - | - |

| 17871 | MSS | c.4485delT | n/a | p.S1459fsX | Frameshift | Damaging | U | - | This Study |

| c.2626C>T | rs121913333 | p.R876X | Nonsense | Damaging | [32] | ||||

| 18090 | MSS | c.3925G>T | n/a | p.E1309X | Nonsense | Damaging | M | LOH | [27] |

| 19199 | MSS | c.646C>T | rs62619935 | p.R216X | Nonsense | Damaging | U | - | [36] |

| 19513 | MSS | c.3740C>T | n/a | p.A1247V | Missense | Benign | M | - | This Study |

| c.3340C>T | rs121913331 | p.R1114X | Nonsense | Damaging | [40] | ||||

| 19906 | MSS | - | - | - | - | - | U | - | - |

| 20039 | MSS | c.4230C>A | n/a | p.C1410X | Nonsense | Damaging | U | - | This Study |

| 20085 | MSI | c.694C>T | rs397515734 | p.R232X | Nonsense | Damaging | M | - | [35] |

| 20187 | MSS | c.3374T>C | rs377278397 | p.V1125A | Missense | Benign | U | - | [41] |

| 21025 | MSI | c.2563_2564dupGA | n/a | p.R856fsX | Frameshift | Damaging | M | - | This Study |

| 21082 | MSS | - | - | - | - | - | U | - | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aitchison, A.; Hakkaart, C.; Day, R.C.; Morrin, H.R.; Frizelle, F.A.; Keenan, J.I. APC Mutations Are Not Confined to Hotspot Regions in Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2020, 12, 3829. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12123829

Aitchison A, Hakkaart C, Day RC, Morrin HR, Frizelle FA, Keenan JI. APC Mutations Are Not Confined to Hotspot Regions in Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer. Cancers. 2020; 12(12):3829. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12123829

Chicago/Turabian StyleAitchison, Alan, Christopher Hakkaart, Robert C. Day, Helen R. Morrin, Frank A. Frizelle, and Jacqueline I. Keenan. 2020. "APC Mutations Are Not Confined to Hotspot Regions in Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer" Cancers 12, no. 12: 3829. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12123829

APA StyleAitchison, A., Hakkaart, C., Day, R. C., Morrin, H. R., Frizelle, F. A., & Keenan, J. I. (2020). APC Mutations Are Not Confined to Hotspot Regions in Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer. Cancers, 12(12), 3829. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12123829