The Hedgehog Signaling Pathway: A Viable Target in Breast Cancer?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Hedgehog Signaling in Mammary Gland Development and Cancer

3. Hedgehog Pathway in Hormone Receptor Positive Breast Cancer

4. Hedgehog Pathway in Triple Negative Breast Cancer

5. Hedgehog Pathway Inhibitors

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howlader, N.; Altekruse, S.F.; Li, C.I.; Chen, V.W.; Clarke, C.A.; Ries, L.A.; Cronin, K.A. US incidence of breast cancer subtypes defined by joint hormone receptor and HER2 status. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.C.; Ro, J.; Andre, F.; Loi, S.; Verma, S.; Iwata, H.; Harbeck, N.; Loibl, S.; Huang Bartlett, C.; Zhang, K.; et al. Palbociclib in Hormone-Receptor-Positive Advanced Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, N.C.; Slamon, D.J.; Ro, J.; Bondarenko, I.; Im, S.A.; Masuda, N.; Colleoni, M.; DeMichele, A.; Loi, S.; Verma, S.; et al. Overall Survival with Palbociclib and Fulvestrant in Advanced Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 1926–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hortobagyi, G.N.; Stemmer, S.M.; Burris, H.A.; Yap, Y.S.; Sonke, G.S.; Paluch-Shimon, S.; Campone, M.; Blackwell, K.L.; Andre, F.; Winer, E.P.; et al. Ribociclib as First-Line Therapy for HR-Positive, Advanced Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1738–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denkert, C.; Liedtke, C.; Tutt, A.; von Minckwitz, G. Molecular alterations in triple-negative breast cancer-the road to new treatment strategies. Lancet 2017, 389, 2430–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadi, V.K.; Davidson, N.E. Practical Approach to Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. J. Oncol. Pract. 2017, 13, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Erkner, A.; Gong, R.; Yao, S.; Taipale, J.; Basler, K.; Beachy, P.A. Hedgehog-mediated patterning of the mammalian embryo requires transporter-like function of dispatched. Cell 2002, 111, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

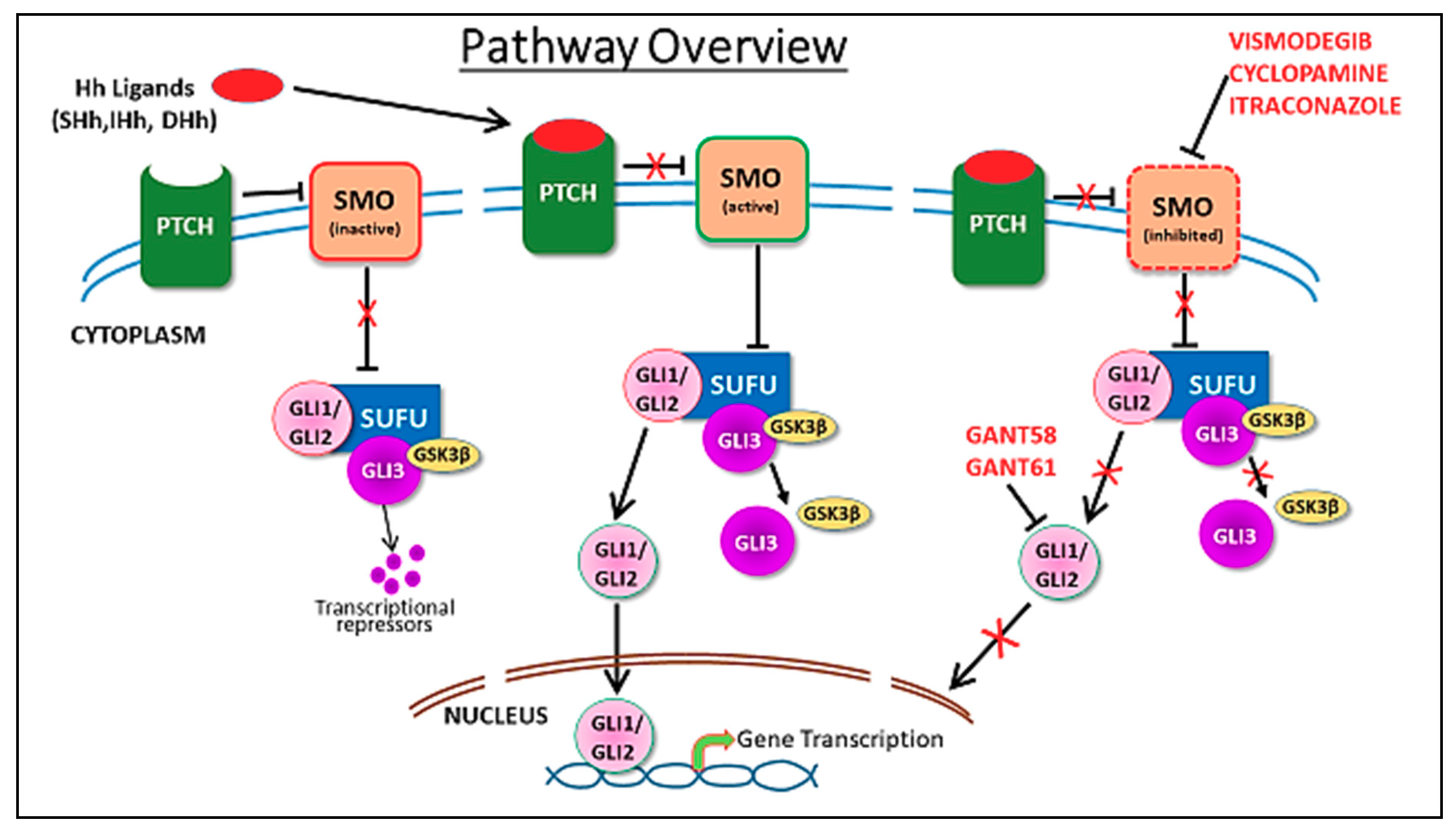

- Sari, I.N.; Phi, L.T.H.; Jun, N.; Wijaya, Y.T.; Lee, S.; Kwon, H.Y. Hedgehog Signaling in Cancer: A Prospective Therapeutic Target for Eradicating Cancer Stem Cells. Cells 2018, 7, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M.T.; Veltmaat, J.M. Next stop, the twilight zone: Hedgehog network regulation of mammary gland development. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 2004, 9, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatsell, S.; Frost, A.R. Hedgehog signaling in mammary gland development and breast cancer. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 2007, 12, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatsell, S.J.; Cowin, P. Gli3-mediated repression of Hedgehog targets is required for normal mammary development. Development 2006, 133, 3661–3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, H.; Nishizaki, Y.; Hui, C.; Nakafuku, M.; Kondoh, H. Regulation of Gli2 and Gli3 activities by an amino-terminal repression domain: Implication of Gli2 and Gli3 as primary mediators of Shh signaling. Development 1999, 126, 3915–3924. [Google Scholar]

- Sekulic, A.; Migden, M.R.; Oro, A.E.; Dirix, L.; Lewis, K.D.; Hainsworth, J.D.; Solomon, J.A.; Yoo, S.; Arron, S.T.; Friedlander, P.A.; et al. Efficacy and safety of vismodegib in advanced basal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 2171–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

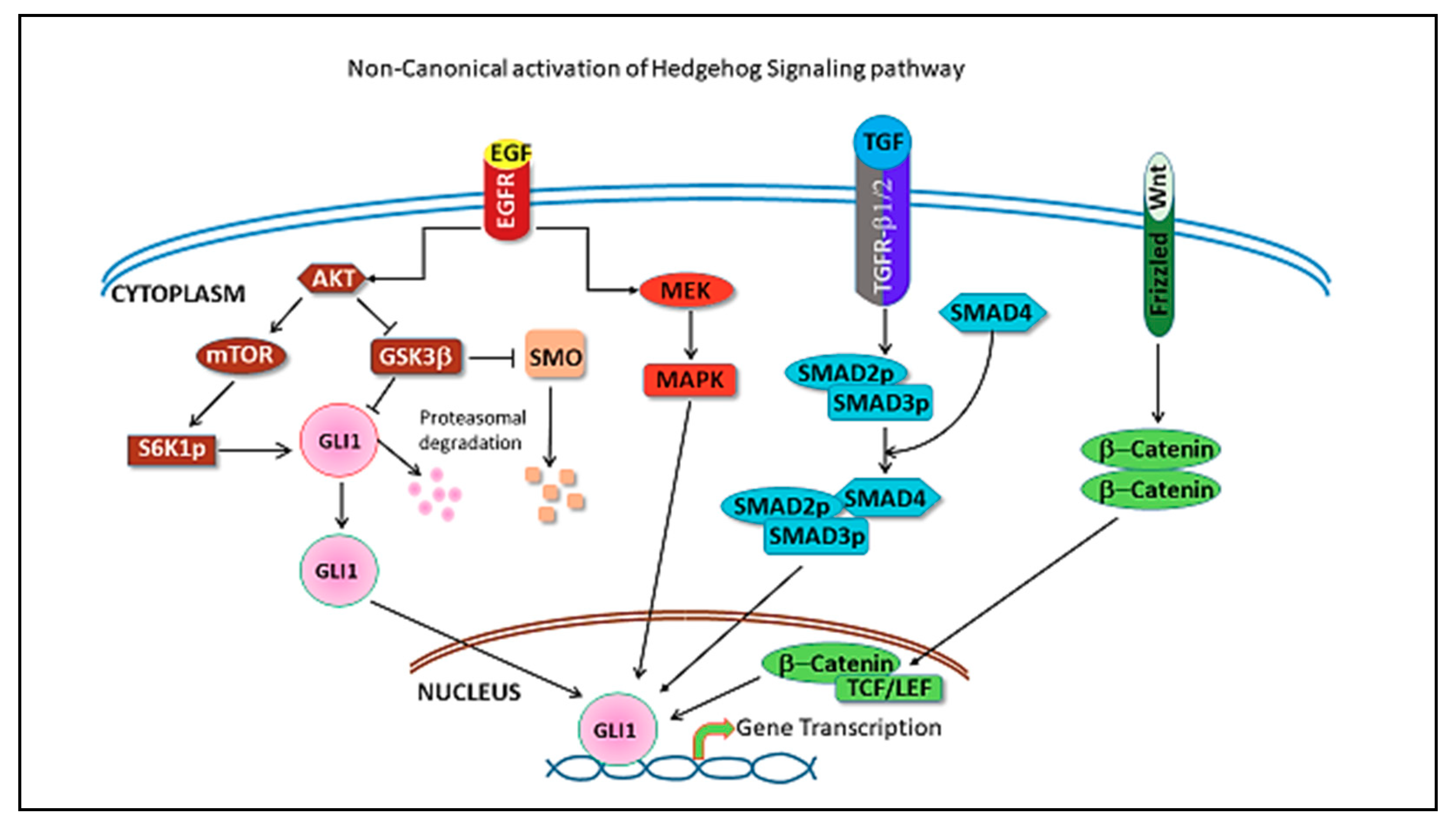

- Aberger, F.; Ruiz, I.A.A. Context-dependent signal integration by the GLI code: The oncogenic load, pathways, modifiers and implications for cancer therapy. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2014, 33, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasper, M.; Schnidar, H.; Neill, G.W.; Hanneder, M.; Klingler, S.; Blaas, L.; Schmid, C.; Hauser-Kronberger, C.; Regl, G.; Philpott, M.P.; et al. Selective modulation of Hedgehog/GLI target gene expression by epidermal growth factor signaling in human keratinocytes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006, 26, 6283–6298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, M.; Rashid, A.; Churi, C.; Vauthey, J.N.; Chang, P.; Li, Y.; Hung, M.C.; Li, D.; Javle, M. Novel therapeutic strategy targeting the Hedgehog signalling and mTOR pathways in biliary tract cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 112, 1042–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regl, G.; Kasper, M.; Schnidar, H.; Eichberger, T.; Neill, G.W.; Philpott, M.P.; Esterbauer, H.; Hauser-Kronberger, C.; Frischauf, A.M.; Aberger, F. Activation of the BCL2 promoter in response to Hedgehog/GLI signal transduction is predominantly mediated by GLI2. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 7724–7731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Po, A.; Silvano, M.; Miele, E.; Capalbo, C.; Eramo, A.; Salvati, V.; Todaro, M.; Besharat, Z.M.; Catanzaro, G.; Cucchi, D.; et al. Noncanonical GLI1 signaling promotes stemness features and in vivo growth in lung adenocarcinoma. Oncogene 2017, 36, 4641–4652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Corte, C.M.; Bellevicine, C.; Vicidomini, G.; Vitagliano, D.; Malapelle, U.; Accardo, M.; Fabozzi, A.; Fiorelli, A.; Fasano, M.; Papaccio, F.; et al. SMO Gene Amplification and Activation of the Hedgehog Pathway as Novel Mechanisms of Resistance to Anti-Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Drugs in Human Lung Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 4686–4697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fan, C.; Gao, P.; Wang, X.; Wei, G.; Wei, J. Estrogen promotes stemness and invasiveness of ER-positive breast cancer cells through Gli1 activation. Mol. Cancer 2014, 13, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merchant, A.A.; Matsui, W. Targeting Hedgehog—A cancer stem cell pathway. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 3130–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- i Altaba, A.R. Therapeutic inhibition of Hedgehog-GLI signaling in cancer: Epithelial, stromal, or stem cell targets? Cancer Cell 2008, 14, 281–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, C.; Park, D.J.; Schmidt, B.; Thomas, N.J.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, T.S.; Janjigian, Y.Y.; Cohen, D.J.; Yoon, S.S. CD44 expression denotes a subpopulation of gastric cancer cells in which Hedgehog signaling promotes chemotherapy resistance. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 3974–3988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, M.; Cazet, A.; Nair, R.; Watkins, D.N.; O’Toole, S.A.; Swarbrick, A. The Hedgehog signalling pathway in breast development, carcinogenesis and cancer therapy. Breast Cancer Res. 2013, 15, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallego, M.I.; Beachy, P.A.; Hennighausen, L.; Robinson, G.W. Differential requirements for shh in mammary tissue and hair follicle morphogenesis. Dev. Biol. 2002, 249, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michno, K.; Boras-Granic, K.; Mill, P.; Hui, C.C.; Hamel, P.A. Shh expression is required for embryonic hair follicle but not mammary gland development. Dev. Biol. 2003, 264, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandramouli, A.; Hatsell, S.J.; Pinderhughes, A.; Koetz, L.; Cowin, P. Gli activity is critical at multiple stages of embryonic mammary and nipple development. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e79845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Lewis, M.T.; Ross, S.; Strickland, P.A.; Sugnet, C.W.; Jimenez, E.; Scott, M.P.; Daniel, C.W. Defects in mouse mammary gland development caused by conditional haploinsufficiency of Patched-1. Development 1999, 126, 5181–5193. [Google Scholar]

- Fiaschi, M.; Rozell, B.; Bergstrom, A.; Toftgard, R.; Kleman, M.I. Targeted expression of GLI1 in the mammary gland disrupts pregnancy-induced maturation and causes lactation failure. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 36090–36101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiaschi, M.; Rozell, B.; Bergstrom, A.; Toftgard, R. Development of mammary tumors by conditional expression of GLI1. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 4810–4817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Dontu, G.; Mantle, I.D.; Patel, S.; Ahn, N.S.; Jackson, K.W.; Suri, P.; Wicha, M.S. Hedgehog signaling and Bmi-1 regulate self-renewal of normal and malignant human mammary stem cells. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 6063–6071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colavito, S.A.; Zou, M.R.; Yan, Q.; Nguyen, D.X.; Stern, D.F. Significance of glioma-associated oncogene homolog 1 (GLI1) expression in claudin-low breast cancer and crosstalk with the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NFkappaB) pathway. Breast Cancer Res. 2014, 16, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javelaud, D.; Alexaki, V.I.; Dennler, S.; Mohammad, K.S.; Guise, T.A.; Mauviel, A. TGF-beta/SMAD/GLI2 signaling axis in cancer progression and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 5606–5610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnidar, H.; Eberl, M.; Klingler, S.; Mangelberger, D.; Kasper, M.; Hauser-Kronberger, C.; Regl, G.; Kroismayr, R.; Moriggl, R.; Sibilia, M.; et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor signaling synergizes with Hedgehog/GLI in oncogenic transformation via activation of the MEK/ERK/JUN pathway. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 1284–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Ma, Q.; Xu, Q.; Liu, H.; Duan, W.; Lei, J.; Ma, J.; Wang, X.; Lv, S.; et al. Sonic hedgehog paracrine signaling activates stromal cells to promote perineural invasion in pancreatic cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 4326–4338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Toole, S.A.; Machalek, D.A.; Shearer, R.F.; Millar, E.K.; Nair, R.; Schofield, P.; McLeod, D.; Cooper, C.L.; McNeil, C.M.; McFarland, A.; et al. Hedgehog overexpression is associated with stromal interactions and predicts for poor outcome in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 4002–4014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.E.; Ghoshal, K.; Ramaswamy, B.; Roy, S.; Datta, J.; Shapiro, C.L.; Jacob, S.; Majumder, S. MicroRNA-221/222 confers tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer by targeting p27Kip1. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 29897–29903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szostakowska, M.; Trebinska-Stryjewska, A.; Grzybowska, E.A.; Fabisiewicz, A. Resistance to endocrine therapy in breast cancer: Molecular mechanisms and future goals. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2019, 173, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, B.; Lu, Y.; Teng, K.Y.; Nuovo, G.; Li, X.; Shapiro, C.L.; Majumder, S. Hedgehog signaling is a novel therapeutic target in tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer aberrantly activated by PI3K/AKT pathway. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 5048–5059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamouille, S.; Xu, J.; Derynck, R. Molecular mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 178–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, M.; Sizemore, S.T.; Lu, Y.; Teng, K.Y.; Basree, M.M.; Reinbolt, R.; Timmers, C.D.; Leone, G.; Ostrowski, M.C.; Majumder, S.; et al. A hedgehog pathway-dependent gene signature is associated with poor clinical outcomes in Luminal A breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 169, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Qi, W.; Cui, Y.; Xuan, Y. GLI1 promotes cancer stemness through intracellular signaling pathway PI3K/Akt/NFkappaB in colorectal adenocarcinoma. Exp. Cell Res. 2018, 373, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, L.; Jiao, M.; Wu, D.; Wu, K.; Li, X.; Zhu, G.; Yang, L.; Wang, X.; Hsieh, J.T.; et al. Genistein inhibits the stemness properties of prostate cancer cells through targeting Hedgehog-Gli1 pathway. Cancer Lett. 2012, 323, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, C.S.; Farnie, G.; Howell, S.J.; Clarke, R.B. Breast cancer stem cells and their role in resistance to endocrine therapy. Horm. Cancer 2011, 2, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souzaki, M.; Kubo, M.; Kai, M.; Kameda, C.; Tanaka, H.; Taguchi, T.; Tanaka, M.; Onishi, H.; Katano, M. Hedgehog signaling pathway mediates the progression of non-invasive breast cancer to invasive breast cancer. Cancer Sci. 2011, 102, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jitariu, A.A.; Cimpean, A.M.; Ribatti, D.; Raica, M. Triple negative breast cancer: The kiss of death. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 46652–46662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, J.; Peng, L.; Sahin, A.A.; Huo, L.; Ward, K.C.; O’Regan, R.; Torres, M.A.; Meisel, J.L. Triple-negative breast cancer has worse overall survival and cause-specific survival than non-triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2017, 161, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, P.; Adams, S.; Rugo, H.S.; Schneeweiss, A.; Barrios, C.H.; Iwata, H.; Dieras, V.; Hegg, R.; Im, S.A.; Shaw Wright, G.; et al. Atezolizumab and Nab-Paclitaxel in Advanced Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2108–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, M.; Im, S.A.; Senkus, E.; Xu, B.; Domchek, S.M.; Masuda, N.; Delaloge, S.; Li, W.; Tung, N.; Armstrong, A.; et al. Olaparib for Metastatic Breast Cancer in Patients with a Germline BRCA Mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litton, J.K.; Rugo, H.S.; Ettl, J.; Hurvitz, S.A.; Goncalves, A.; Lee, K.H.; Fehrenbacher, L.; Yerushalmi, R.; Mina, L.A.; Martin, M.; et al. Talazoparib in Patients with Advanced Breast Cancer and a Germline BRCA Mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 753–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noman, A.S.; Uddin, M.; Rahman, M.Z.; Nayeem, M.J.; Alam, S.S.; Khatun, Z.; Wahiduzzaman, M.; Sultana, A.; Rahman, M.L.; Ali, M.Y.; et al. Overexpression of sonic hedgehog in the triple negative breast cancer: Clinicopathological characteristics of high burden breast cancer patients from Bangladesh. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 18830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, Y.; Ohta, Y.; Saitoh, W.; Yamashita, T.; Kanomata, N.; Moriya, T.; Kurebayashi, J. Anti-cell growth and anti-cancer stem cell activities of the non-canonical hedgehog inhibitor GANT61 in triple-negative breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer 2017, 24, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Kwon, Y.J.; Frolova, N.; Steg, A.D.; Yuan, K.; Johnson, M.R.; Grizzle, W.E.; Desmond, R.A.; Frost, A.R. Gli1 promotes cell survival and is predictive of a poor outcome in ERalpha-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2010, 123, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorechovsky, I.; Benediktsson, K.; Toftgard, R. The patched/hedgehog/smoothened signalling pathway in human breast cancer: No evidence for H133Y SHH, PTCH and SMO mutations. Eur. J. Cancer 1999, 35, 711–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicking, C.; Evans, T.; Henk, B.; Hayward, N.; Simms, L.A.; Chenevix-Trench, G.; Pietsch, T.; Wainwright, B. No evidence for the H133Y mutation in SONIC HEDGEHOG in a collection of common tumour types. Oncogene 1998, 16, 1091–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palle, K.; Mani, C.; Tripathi, K.; Athar, M. Aberrant GLI1 Activation in DNA Damage Response, Carcinogenesis and Chemoresistance. Cancers (Basel) 2015, 7, 2330–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Qu, Y.; Jin, Y.; Yu, Y.; Deng, N.; Wawrowsky, K.; Zhang, X.; Li, N.; Bose, S.; Wang, Q.; et al. FOXC1 Activates Smoothened-Independent Hedgehog Signaling in Basal-like Breast Cancer. Cell Rep. 2015, 13, 1046–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.; Jin, Y.; Han, B.; Qu, Y.; Gao, B.; Giuliano, A.E.; Cui, X. Identification of EGF-NF-kappaB-FOXC1 signaling axis in basal-like breast cancer. Cell Commun. Signal. 2017, 15, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschmann-Jax, C.; Foster, A.E.; Wulf, G.G.; Nuchtern, J.G.; Jax, T.W.; Gobel, U.; Goodell, M.A.; Brenner, M.K. A distinct "side population" of cells with high drug efflux capacity in human tumor cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 14228–14233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims-Mourtada, J.; Opdenaker, L.M.; Davis, J.; Arnold, K.M.; Flynn, D. Taxane-induced hedgehog signaling is linked to expansion of breast cancer stem-like populations after chemotherapy. Mol. Carcinog. 2015, 54, 1480–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crum, C.P.; McKeon, F.D. p63 in epithelial survival, germ cell surveillance, and neoplasia. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2010, 5, 349–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memmi, E.M.; Sanarico, A.G.; Giacobbe, A.; Peschiaroli, A.; Frezza, V.; Cicalese, A.; Pisati, F.; Tosoni, D.; Zhou, H.; Tonon, G.; et al. p63 Sustains self-renewal of mammary cancer stem cells through regulation of Sonic Hedgehog signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 3499–3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Zhou, T.C.; Lei, X.X.; Wang, C.; Yan, M.; Wang, Z.F.; Liu, W.; Wang, J.; Ming, K.H.; Wang, B.C.; et al. Inhibition of Sonic Hedgehog Signaling Pathway by Thiazole Antibiotic Thiostrepton Attenuates the CD44+/CD24-Stem-Like Population and Sphere-Forming Capacity in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 38, 1157–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazet, A.S.; Hui, M.N.; Elsworth, B.L.; Wu, S.Z.; Roden, D.; Chan, C.L.; Skhinas, J.N.; Collot, R.; Yang, J.; Harvey, K.; et al. Targeting stromal remodeling and cancer stem cell plasticity overcomes chemoresistance in triple negative breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenti, G.; Quinn, H.M.; Heynen, G.; Lan, L.; Holland, J.D.; Vogel, R.; Wulf-Goldenberg, A.; Birchmeier, W.; et al. Cancer Stem Cells Regulate Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts via Activation of Hedgehog Signaling in Mammary Gland Tumors. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 2134–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.J.; Hurst, D.R.; Steg, A.D.; Yuan, K.; Vaidya, K.S.; Welch, D.R.; Frost, A.R. Gli1 enhances migration and invasion via up-regulation of MMP-11 and promotes metastasis in ERalpha negative breast cancer cell lines. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2011, 28, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Geradts, J.; Dewhirst, M.W.; Lo, H.W. Upregulation of VEGF-A and CD24 gene expression by the tGLI1 transcription factor contributes to the aggressive behavior of breast cancer cells. Oncogene 2012, 31, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Mauro, C.; Rosa, R.; D’Amato, V.; Ciciola, P.; Servetto, A.; Marciano, R.; Orsini, R.C.; Formisano, L.; De Falco, S.; Cicatiello, V.; et al. Hedgehog signalling pathway orchestrates angiogenesis in triple-negative breast cancers. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 116, 1425–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, H.L.; Pursell, B.; Chang, C.; Shaw, L.M.; Mao, J.; Simin, K.; Kumar, P.; Vander Kooi, C.W.; Shultz, L.D.; Greiner, D.L.; et al. GLI1 regulates a novel neuropilin-2/alpha6beta1 integrin based autocrine pathway that contributes to breast cancer initiation. EMBO Mol. Med. 2013, 5, 488–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Samant, R.S.; Shevde, L.A. Nonclassical activation of Hedgehog signaling enhances multidrug resistance and makes cancer cells refractory to Smoothened-targeting Hedgehog inhibition. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 11824–11833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonnissen, A.; Isebaert, S.; Haustermans, K. Targeting the Hedgehog signaling pathway in cancer: Beyond Smoothened. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 13899–13913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruch, J.M.; Kim, E.J. Hedgehog signaling pathway and cancer therapeutics: Progress to date. Drugs 2013, 73, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Frolova, N.; Sadlonova, A.; Novak, Z.; Steg, A.; Page, G.P.; Welch, D.R.; Lobo-Ruppert, S.M.; Ruppert, J.M.; Johnson, M.R.; et al. Hedgehog signaling and response to cyclopamine differ in epithelial and stromal cells in benign breast and breast cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2006, 5, 674–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, D.; Demko, S.; Shord, S.; Zhao, H.; Chen, H.; He, K.; Putman, A.; Helms, W.; Keegan, P.; Pazdur, R. FDA Approval Summary: Sonidegib for Locally Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 2377–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.J.; Hatton, B.A.; Villavicencio, E.H.; Khanna, P.C.; Friedman, S.D.; Ditzler, S.; Pullar, B.; Robison, K.; White, K.F.; Tunkey, C.; et al. Hedgehog pathway inhibitor saridegib (IPI-926) increases lifespan in a mouse medulloblastoma model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 7859–7864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, G.; Sivaraman, A.; Lee, K. Development of taladegib as a sonic hedgehog signaling pathway inhibitor. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2017, 40, 1390–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, H.; Kondo, S.; Yoshikawa, S.; Inoue, K.; Andre, V.; Tajimi, M.; Murakami, H. A phase I and pharmacokinetic study of taladegib, a Smoothened inhibitor, in Japanese patients with advanced solid tumors. Investig. New Drugs 2018, 36, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savona, M.R.; Pollyea, D.A.; Stock, W.; Oehler, V.G.; Schroeder, M.A.; Lancet, J.; McCloskey, J.; Kantarjian, H.M.; Ma, W.W.; Shaik, M.N.; et al. Phase Ib Study of Glasdegib, a Hedgehog Pathway Inhibitor, in Combination with Standard Chemotherapy in Patients with AML or High-Risk MDS. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 2294–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atwood, S.X.; Sarin, K.Y.; Whitson, R.J.; Li, J.R.; Kim, G.; Rezaee, M.; Ally, M.S.; Kim, J.; Yao, C.; Chang, A.L.; et al. Smoothened variants explain the majority of drug resistance in basal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell 2015, 27, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Aftab, B.T.; Tang, J.Y.; Kim, D.; Lee, A.H.; Rezaee, M.; Kim, J.; Chen, B.; King, E.M.; Borodovsky, A.; et al. Itraconazole and arsenic trioxide inhibit Hedgehog pathway activation and tumor growth associated with acquired resistance to smoothened antagonists. Cancer Cell 2013, 23, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Tang, J.Y.; Gong, R.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.J.; Clemons, K.V.; Chong, C.R.; Chang, K.S.; Fereshteh, M.; Gardner, D.; et al. Itraconazole, a commonly used antifungal that inhibits Hedgehog pathway activity and cancer growth. Cancer Cell 2010, 17, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, J.J.; Kim, J.; Gardner, D.; Beachy, P.A. Arsenic antagonizes the Hedgehog pathway by preventing ciliary accumulation and reducing stability of the Gli2 transcriptional effector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 13432–13437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, E.M.; Ringer, L.; Bulut, G.; Sajwan, K.P.; Hall, M.D.; Lee, Y.C.; Peaceman, D.; Ozdemirli, M.; Rodriguez, O.; Macdonald, T.J.; et al. Arsenic trioxide inhibits human cancer cell growth and tumor development in mice by blocking Hedgehog/GLI pathway. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, G.N.; Jimeno, A. Emerging from their burrow: Hedgehog pathway inhibitors for cancer. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2016, 25, 1153–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelakantan, D.; Zhou, H.; Oliphant, M.U.J.; Zhang, X.; Simon, L.M.; Henke, D.M.; Shaw, C.A.; Wu, M.F.; Hilsenbeck, S.G.; White, L.D.; et al. EMT cells increase breast cancer metastasis via paracrine GLI activation in neighbouring tumour cells. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenuto, M.; Masuelli, L.; De Smaele, E.; Fantini, M.; Mattera, R.; Cucchi, D.; Bonanno, E.; Di Stefano, E.; Frajese, G.V.; Orlandi, A.; et al. In vitro and in vivo inhibition of breast cancer cell growth by targeting the Hedgehog/GLI pathway with SMO (GDC-0449) or GLI (GANT-61) inhibitors. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 9250–9270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, S.K.; Khan, J.S.; Shah, S.T.A.; Wang, F.; Ye, L.; Jiang, W.G.; Malik, M.F.A. Involvement of hedgehog pathway in early onset, aggressive molecular subtypes and metastatic potential of breast cancer. Cell Commun. Signal. 2018, 16, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Q.S.; Mahipal, A.; Schuler, M.; De Braud, F.G.M.; Dirix, L.; Rampersad, A.; Zhou, J.; Wu, Y.; Kalambakas, S.; Wen, P.Y. Dose-escalation study of sonidegib (LDE225) plus buparlisib (BKM120) in patients with advanced solid tumors. Ann. Oncol. 2014, 25, iv147–iv148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Li, Z.Y.; Liu, W.P.; Zhao, M.R. Crosstalk between Wnt/beta-catenin and Hedgehog/Gli signaling pathways in colon cancer and implications for therapy. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2015, 16, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, O.; Kondo, M.; Fujita, T.; Usami, N.; Fukui, T.; Shimokata, K.; Ando, T.; Goto, H.; Sekido, Y. Enhancement of GLI1-transcriptional activity by beta-catenin in human cancer cells. Oncol. Rep. 2006, 16, 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Lin, P.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, M.; Pang, L. Wnt3a-regulated TCF4/beta-catenin complex directly activates the key Hedgehog signalling genes Smo and Gli1. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018, 16, 2101–2107. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, L.P.; DaSilva, K.A.; Mitchell, J. Regulation of Indian hedgehog mRNA levels in chondrocytic cells by ERK1/2 and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases. J. Cell. Physiol. 2005, 203, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirkisoon, S.R.; Carpenter, R.L.; Rimkus, T.; Anderson, A.; Harrison, A.; Lange, A.M.; Jin, G.; Watabe, K.; Lo, H.W. Interaction between STAT3 and GLI1/tGLI1 oncogenic transcription factors promotes the aggressiveness of triple-negative breast cancers and HER2-enriched breast cancer. Oncogene 2018, 37, 2502–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, W.; Hutzinger, M.; Elmer, D.P.; Parigger, T.; Sternberg, C.; Cegielkowski, L.; Zaja, M.; Leban, J.; Michel, S.; Hamm, S.; et al. DYRK1B as therapeutic target in Hedgehog/GLI-dependent cancer cells with Smoothened inhibitor resistance. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 7134–7148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, W.; Peer, E.; Elmer, D.P.; Sternberg, C.; Tesanovic, S.; Del Burgo, P.; Coni, S.; Canettieri, G.; Neureiter, D.; Bartz, R.; et al. Targeting class I histone deacetylases by the novel small molecule inhibitor 4SC-202 blocks oncogenic hedgehog-GLI signaling and overcomes smoothened inhibitor resistance. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 142, 968–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coni, S.; Di Magno, L.; Serrao, S.M.; Kanamori, Y.; Agostinelli, E.; Canettieri, G. Polyamine Metabolism as a Therapeutic Target inHedgehog-Driven Basal Cell Carcinomaand Medulloblastoma. Cells 2019, 8, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Magno, L.; Manzi, D.; D’Amico, D.; Coni, S.; Macone, A.; Infante, P.; Di Marcotullio, L.; De Smaele, E.; Ferretti, E.; Screpanti, I.; et al. Druggable glycolytic requirement for Hedgehog-dependent neuronal and medulloblastoma growth. Cell Cycle 2014, 13, 3404–3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, A.; Metge, B.J.; Bailey, S.K.; Chen, D.; Chandrashekar, D.S.; Varambally, S.; Samant, R.S.; Shevde, L.A. Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling reprograms the dysfunctional immune microenvironment in breast cancer. Oncoimmunology 2019, 8, 1548241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Borrego, M.; Jimenez, B.; Antolin, S.; Garcia-Saenz, J.A.; Corral, J.; Jerez, Y.; Trigo, J.; Urruticoechea, A.; Colom, H.; Gonzalo, N.; et al. A phase Ib study of sonidegib (LDE225), an oral small molecule inhibitor of smoothened or Hedgehog pathway, in combination with docetaxel in triple negative advanced breast cancer patients: GEICAM/2012-12 (EDALINE) study. Investig. New Drugs 2019, 37, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bhateja, P.; Cherian, M.; Majumder, S.; Ramaswamy, B. The Hedgehog Signaling Pathway: A Viable Target in Breast Cancer? Cancers 2019, 11, 1126. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11081126

Bhateja P, Cherian M, Majumder S, Ramaswamy B. The Hedgehog Signaling Pathway: A Viable Target in Breast Cancer? Cancers. 2019; 11(8):1126. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11081126

Chicago/Turabian StyleBhateja, Priyanka, Mathew Cherian, Sarmila Majumder, and Bhuvaneswari Ramaswamy. 2019. "The Hedgehog Signaling Pathway: A Viable Target in Breast Cancer?" Cancers 11, no. 8: 1126. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11081126

APA StyleBhateja, P., Cherian, M., Majumder, S., & Ramaswamy, B. (2019). The Hedgehog Signaling Pathway: A Viable Target in Breast Cancer? Cancers, 11(8), 1126. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11081126