Investigation of III-Nitride MEMS Pressure Sensor for High-Temperature Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

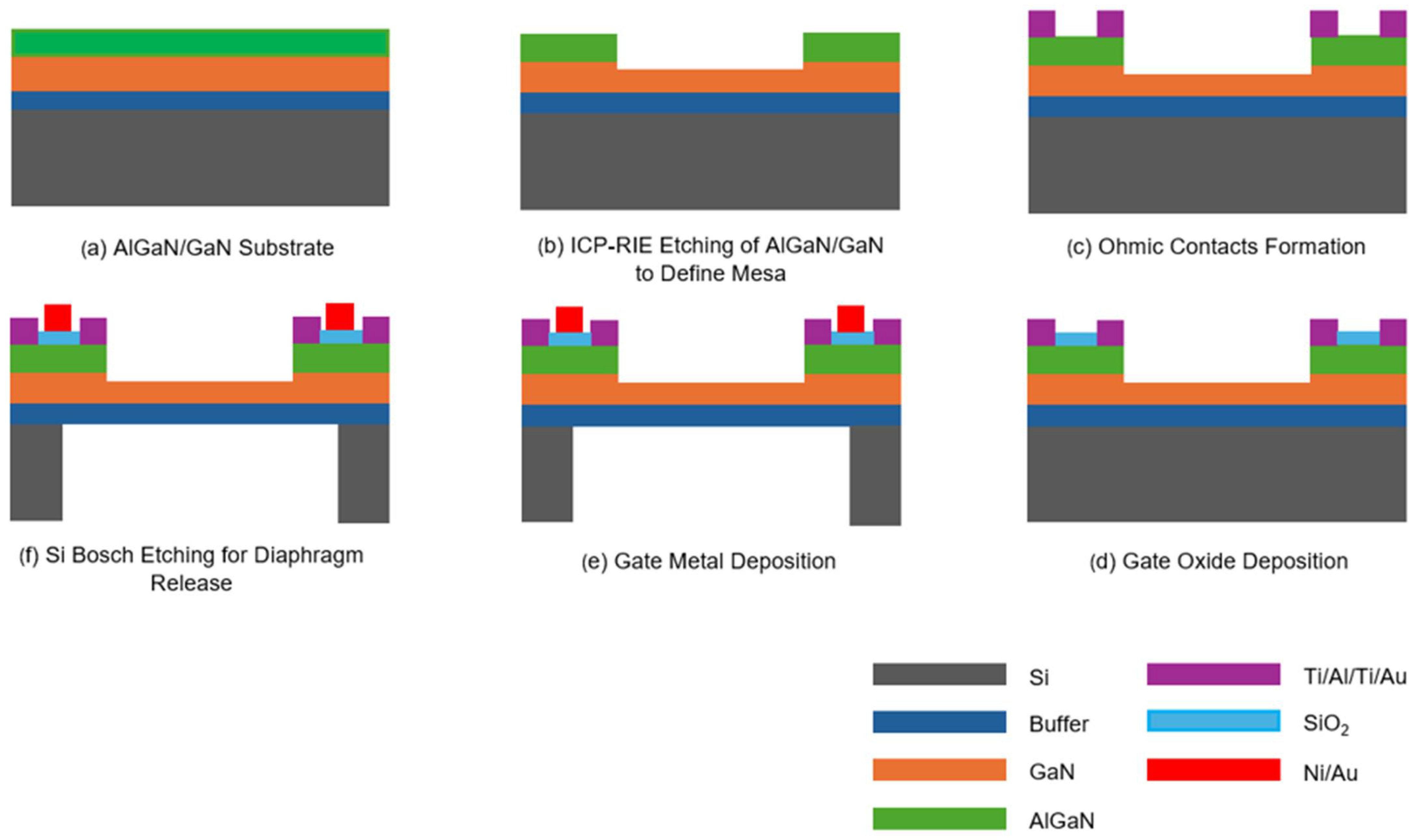

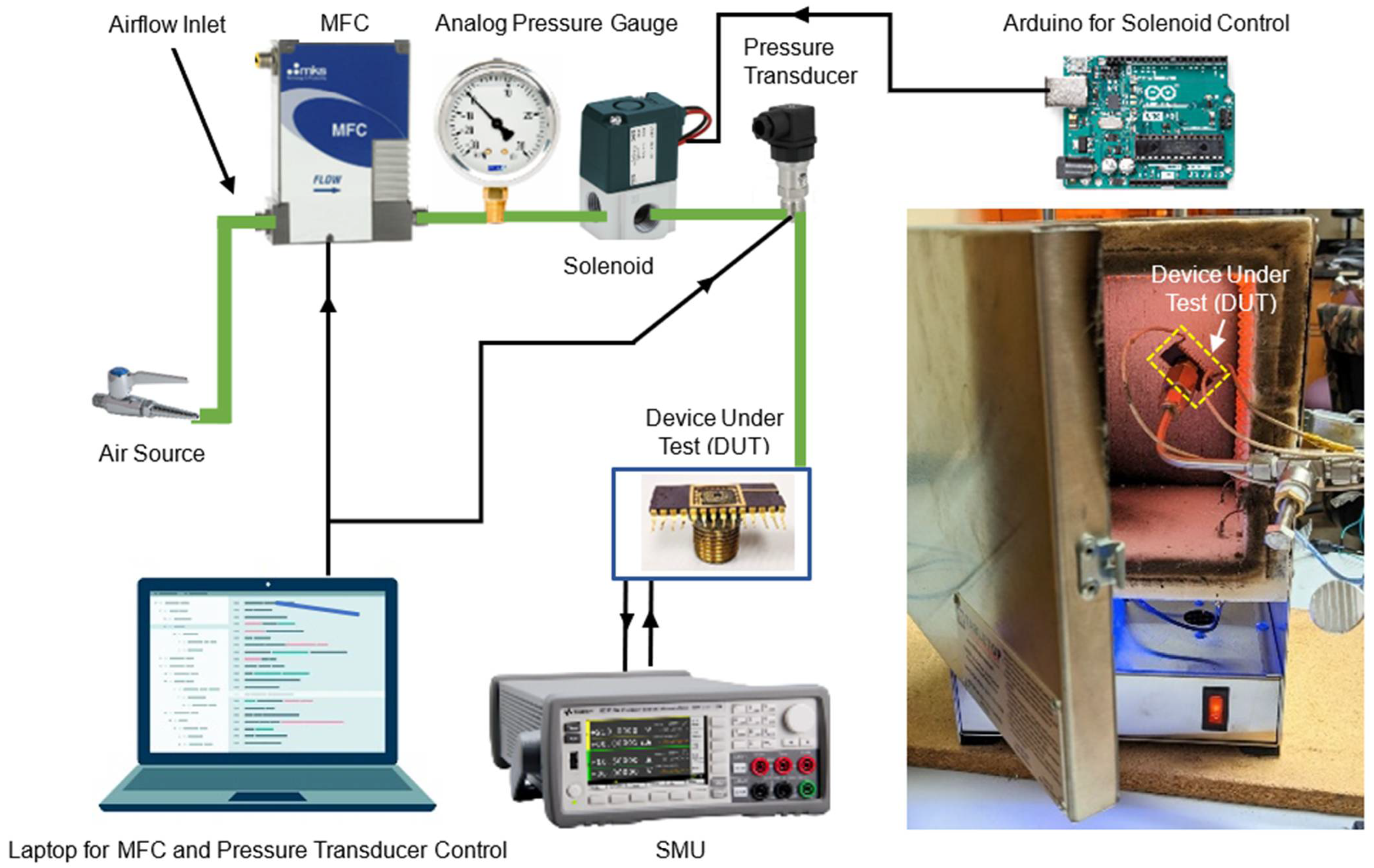

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussions

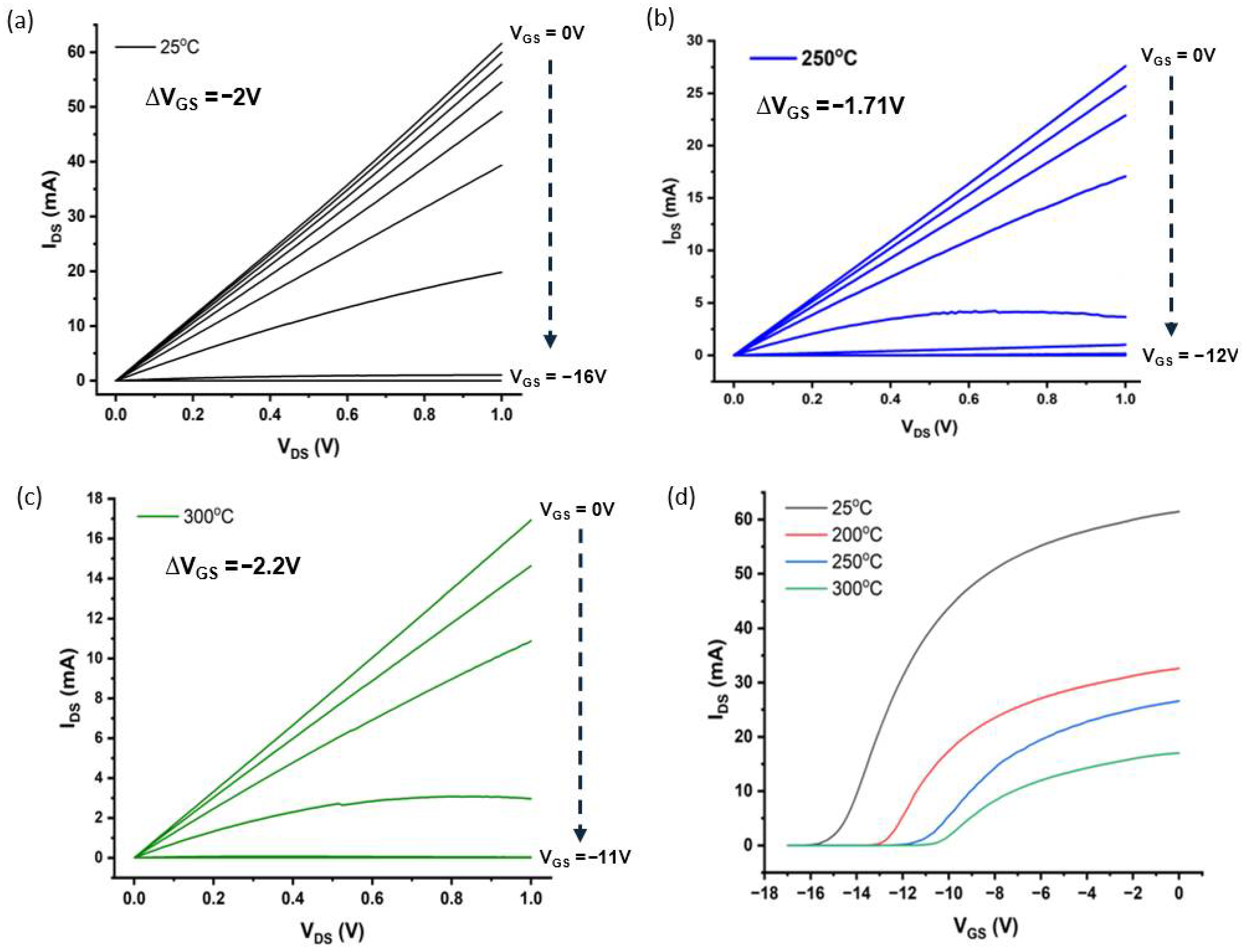

3.1. Temperature-Dependent I-V Characteristics

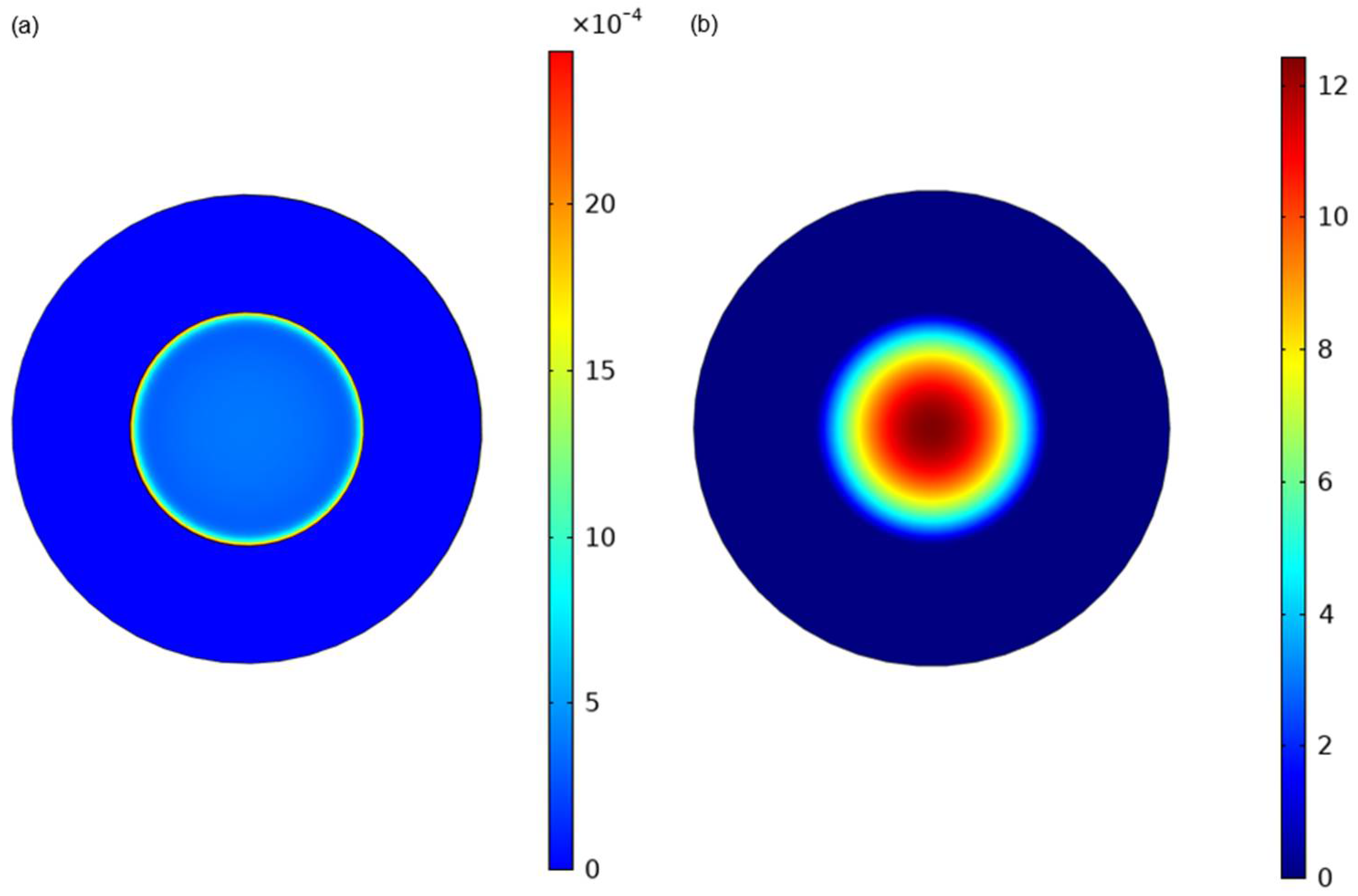

3.2. Theoretical Modeling for 2DEG Formation and Relationship with Strain

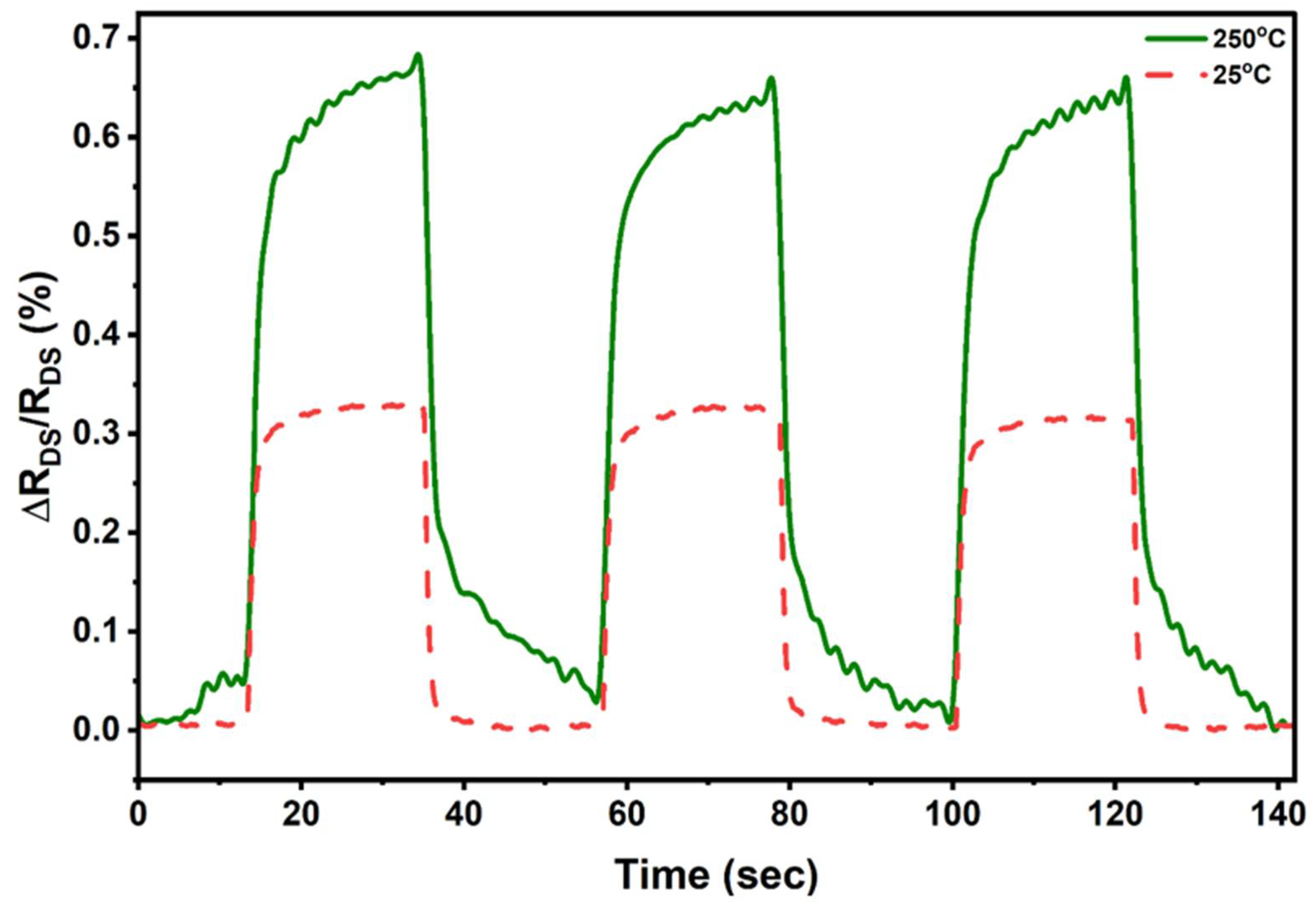

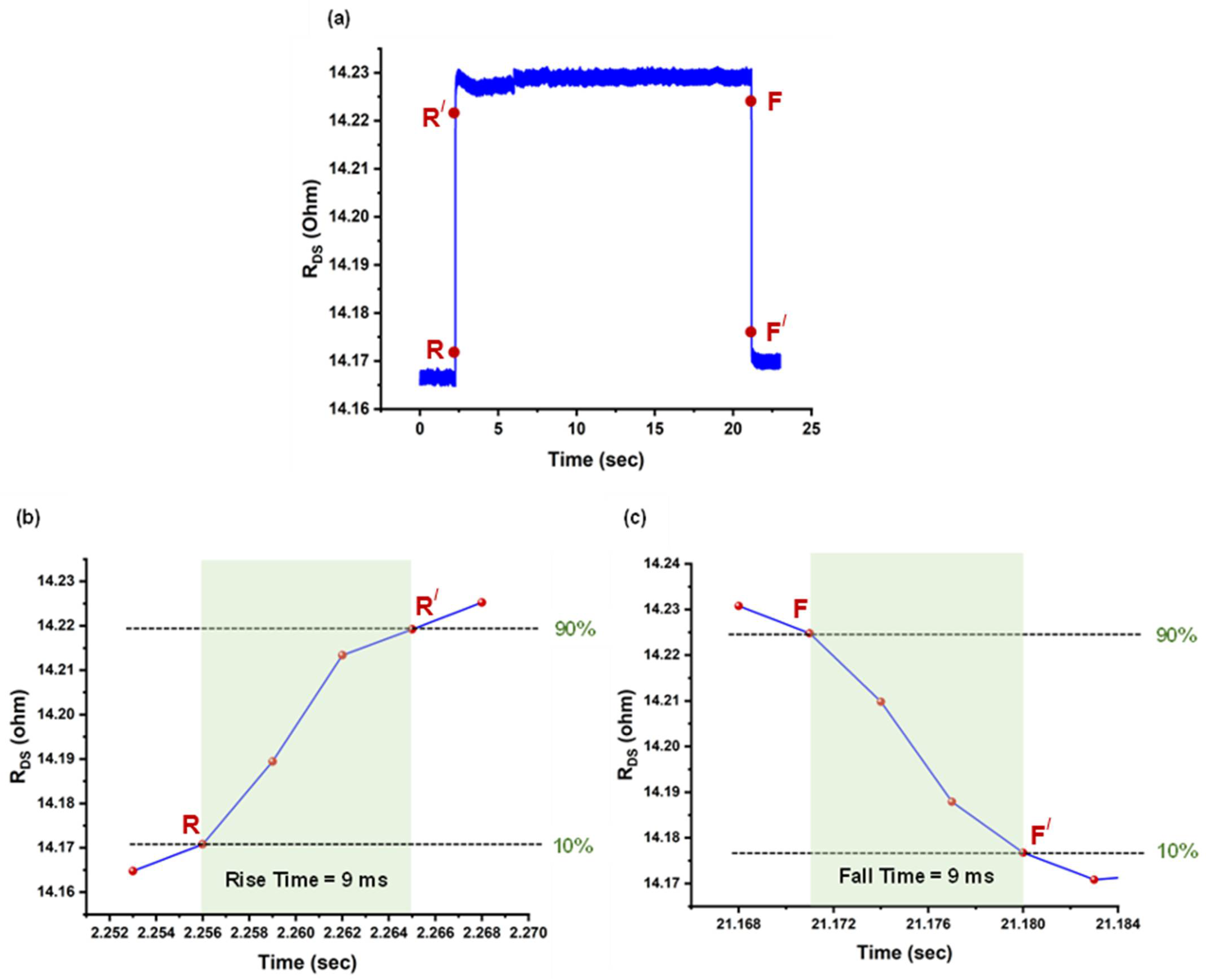

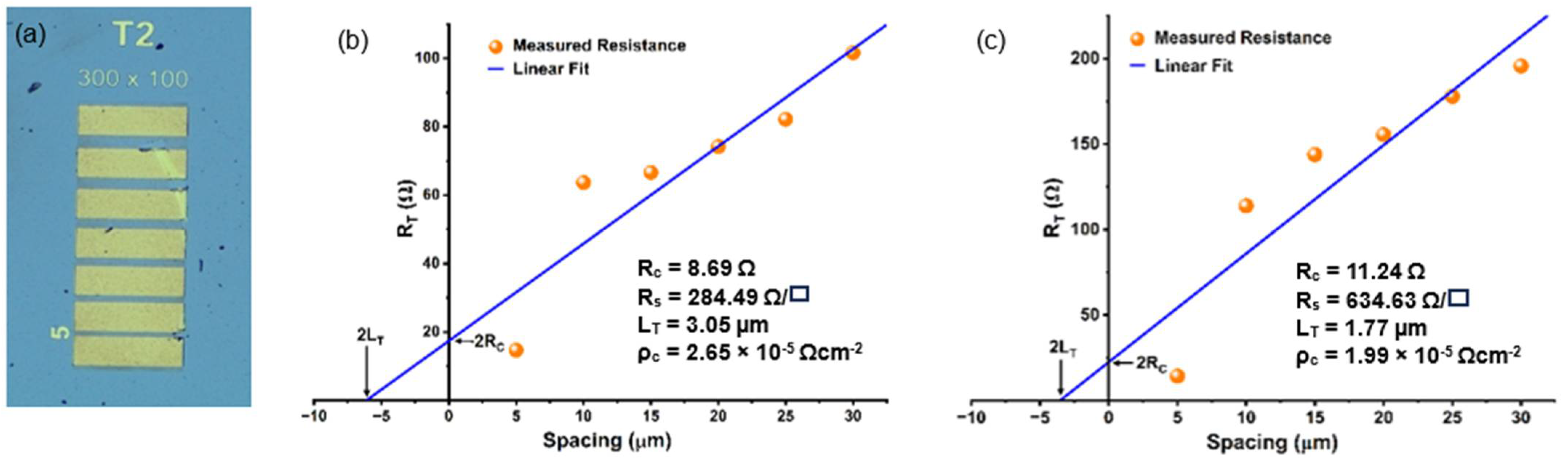

3.3. Sensor Characterization at Room Temperature

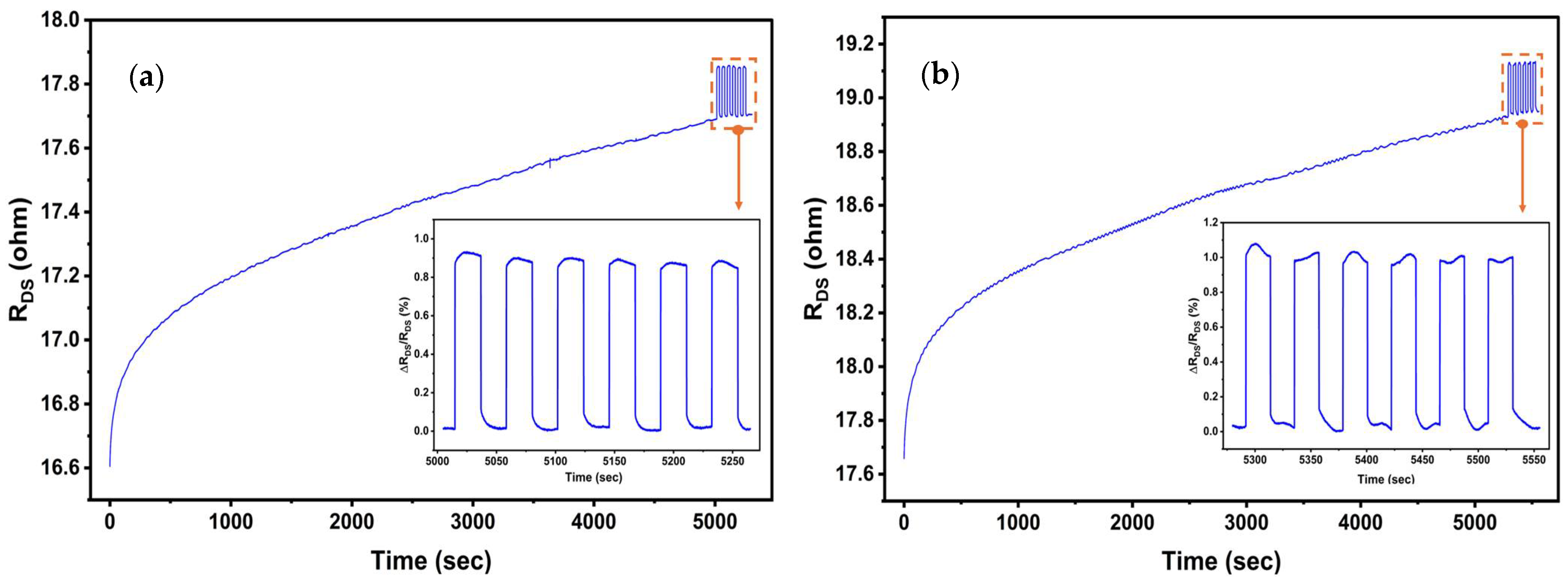

3.4. Sensor Characterization at Elevated Temperatures

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, Y.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Kuang, M. Materials and Sensing Mechanisms for High-Temperature Pressure Sensors: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 26910–26924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Ma, Z.; Ma, J.; Yang, L.; Wei, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yang, F.; Wang, X. Recent Progress of Miniature MEMS Pressure Sensors. Micromachines 2020, 11, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prio, M.H.; Morshed, M.; Muthusamy, L.; Gajula, D.; Koley, G. High Temperature Characterization of III-Nitride Pressure Sensors. In Proceedings of the 2025 Device Research Conference (DRC), Durham, NC, USA, 22–25 June 2025; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Gajula, D.; Jahangir, I.; Koley, G. High Temperature AlGaN/GaN Membrane Based Pressure Sensors. Micromachines 2018, 9, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aref, S.H.; Zibaii, M.I.; Latifi, H. An improved fiber optic pressure and temperature sensor for downhole application. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2009, 20, 034009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusiek, G.; Niewczas, P.; McDonald, J.R. Design of a highly accurate optical sensor system for pressure and temperature monitoring in oil wells. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference, Singapore, 5–7 May 2009; pp. 574–578. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, B.; Pickrell, G.R.; Zhang, P.; Duan, Y.; Peng, W.; Xu, J.; Huang, Z.; Deng, J.; Xiao, H.; Wang, Z.; et al. Fiber optic pressure and temperature sensors for oil down hole application. In Proceedings of the SPIE Fiber Optic Sensor Technology and Applications, Prague, Czech Republic, 14 February 2002; p. 4578. [Google Scholar]

- Chapin, C.A.; Miller, R.A.; Dowling, K.M.; Chen, R.; Senesky, D.G. InAlN/GaN high electron mobility micro-pressure sensors for high-temperature environments. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2017, 263, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayerdi, I.; Castaño, E.; García-Alonso, A.; Gracia, J. High-temperature ceramic pressure sensor. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 1997, 60, 72–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, K.-H.; Huh, H.; Li, Z.; Lu, N. Soft Capacitive Pressure Sensors: Trends, Challenges, and Perspectives. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 3442–3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Liu, K.; Xu, J.; Ye, M.; Yang, T.; Qi, T.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhang, H. High-performance multifunctional piezoresistive/piezoelectric pressure sensor with thermochromic function for wearable monitoring. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 459, 141648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Lin, L.; Wang, Z.L. Triboelectric nanogenerators as self-powered active sensors. Nano Energy 2015, 11, 436–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, Z.; Haneef, I.; Udrea, F. Material selection for optimum design of MEMS pressure sensors. Microsyst. Technol. 2020, 26, 2751–2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Huang, M.; Wu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Xia, Y.; Yang, P.; Fan, S.; Lu, X.; Yang, X.; Liang, L.; et al. Advances in high-performance MEMS pressure sensors: Design, fabrication, and packaging. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2023, 9, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belwanshi, V.; Philip, S.; Topkar, A. Performance Study of MEMS Piezoresistive Pressure Sensors at Elevated Temperatures. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 9313–9320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uppalapati, B.; Gajula, D.; Bava, M.; Muthusamy, L.; Koley, G. Low-Power AlGaN/GaN Triangular Microcantilever for Air Flow Detection. Sensors 2023, 23, 7465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Chen, H.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, Y.; Ji, Z.; Li, L.; Yang, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhou, J.; Fu, Y. Advances in Silicon Carbides and Their MEMS Pressure Sensors for High Temperature and Pressure Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 26117–26155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroetz, G.H.; Eickhoff, M.H.; Moeller, H. Silicon compatible materials for harsh environment sensors. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 1999, 74, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclaire, P.; Frayssient, E.; Morelle, C.; Cordier, Y.; Theron, D.; Faucher, M. Piezoelectric MEMS resonators based on ultrathin epitaxial GaN heterostructures on Si. J. Micomechanics Microengineering 2016, 26, 105015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uppalapati, B.; Kota, A.; Azad, S.; Muthusamy, L.; Tran, B.T.; Leach, J.H.; Splawn, H.; Gajula, D.; Chodavarapu, V.P.; Koley, G. Indium Tin Oxide (ITO) based Ohmic Contacts on Bulk n-GaN Substrate. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2022, 11, 115008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eickhoff, M.; Ambacher, O.; Krotz, G.; Stutzmann, M. Piezoresistivity of AlxGa1-xN layers and AlxGa1-xN/GaN heterostructures. J. Appl. Phys. 2001, 90, 3383–3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.S.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.; Ren, F.; Baik, K.; Pearton, S.J. Effect of external strain on the conductivity of AlGaN/GaN high-electron-mobility transistors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2003, 83, 4845–4847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, A.D.; Gupta, A.; Chu, M.; Parthasarathy, S.; Linthicum, K.J.; Johnson, J.W.; Thompson, S.E. Extraction of AlGaN/GaN HEMT Gauge Factor in the Presence of Traps. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2010, 31, 665–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, K.; Khandelwal, S.; Sammoura, F.; Kazama, A.; Hu, C.; Lin, L. Piezoelectricity-Induced Schottky Barrier Height Variations in AlGaN/GaN High Electron Mobility Transistors. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2015, 36, 902–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.N.G.; Ren, F.; Pearton, S.; Kang, B.; Kim, S.; Gila, B.; Abernathy, C.; Chyi, J.-I.; Johnson, W.; Lin, J. Piezoelectric polarization-induced two dimensional electron gases in AlGaN/GaN heteroepitaxial structures: Application for micro-pressure sensors. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2005, 409, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalamarthy, A.S.; Senesky, D.G. Strain- and temperature-induced effects in AlGaN/GaN high electron mobility transistors. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2016, 31, 035024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.S.; Kim, S.; Ren, F.; Johnson, J.W.; Therrien, R.J.; Rajagopal, P.; Roberts, J.C.; Pinker, E.L.; Linthicum, K.J.; Chu, S.N.G.; et al. Pressure-induced changes in the conductivity of AlGaN/GaN high-electron mobility-transistor membranes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2004, 85, 2962–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulbar, L.; Edwards, M.J.; Vittoz, S.; Vanko, G.; Brinkfeldt, K.; Rufer, L.; Johander, P.; Lalinsky, T.; Bowen, C.R.; Allsopp, D.W.E. Effect of bias conditions on pressure sensors based on AlGaN/GaN High Electron Mobility Transistor. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2013, 194, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, M.J.; Le Boulbar, E.D.; Vittoz, S.; Vanko, G.; Brinkfeldt, K.; Rufer, L.; Johander, P.; Lalinský, T.; Bowen, C.R.; Allsopp, D.W.E. Pressure and temperature dependence of GaN/AlGaN high electron mobility transistor based sensors on a sapphire membrane. Phys. Status Solidi C 2012, 9, 960–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Hu, D.; Liu, Z.; Middelburg, L.M.; Vollebregt, S.; Sarro, P.M.; Zhang, G. Low power AlGaN/GaN MEMS pressure sensor for high vacuum application. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2020, 314, 112217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toure, A.; Halidou, I.; Benzarti, Z.; Fouzri, A.; Bchetnia, A.; Jani, B.E. Characterization of low Al content AlxGa1-xN epitaxial films grown by atmospheric-pressure MOVPE. Phys. Status Solidi A 2012, 209, 977–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsvetkov, D.; Vaudo, R.P.; Wang, X.Q.; Preble, E.A.; Molnar, R.J. Growth of Submicron AlGaN/GaN/AlGaN Heterostructures by Hydride Vapor Phase Epitaxy. Phys. Status Solidi A 2001, 188, 429–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, J.B.; Tang, H.; Bardwell, J.A.; Coleridge, P. Growth of High Mobility AlGaN/GaN Heterostructuresby Ammonia-Molecular Beam Epitaxy. Phys. Status Solidi A 1999, 176, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Eriksen, H.; Childress, K.; Fink, A.; Hoffman, M. High temperature smart-cut SOI pressure sensor. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2009, 154, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorman, C.A.; Parro, R.J. Micro- and nanomechanical structures for silicon carbide MEMS and NEMS. Phys. Status Solidi B 2008, 245, 1404–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Li, C.; Xiong, J.; Jia, P.; Zhang, W.; Liu, J.; Xue, C.; Hong, Y.; Ren, Z.; Luo, T. A High Temperature Capacitive Pressure Sensor Based on Alumina Ceramic for in Situ Measurement at 600 °C. Sensors 2014, 14, 2417–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Mehregany, M. A silicon carbide capacitive pressure sensor for in-cylinder pressure measurement. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2008, 145–146, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.S.; Kim, J.; Jang, S.; Ren, F.; Johnson, J.W.; Therrien, R.J.; Rajagopal, P.; Roberts, J.C.; Piner, E.L.; Linthicum, K.J.; et al. Capacitance pressure sensor based on GaN high-electron-mobility transistor-on-Si membrane. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2005, 86, 253502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, U.K.; Shen, L.; Kazior, T.E.; Wu, Y.F. GaN-Based RF Power Devices and Amplifiers. Proc. IEEE 2008, 96, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suria, A.J.; Yalamarthy, A.S.; Heuser, T.A.; Bruefach, A.; Chapin, C.A.; So, H.; Senesky, D.G. Thickness Engineering of Atomic Layer Deposited Al2O3 Films to Suppress Interfacial Reaction and Diffusion of Ni/Au Gate Metal in AlGaN/GaN HEMTs up to 600 °C in Air. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 110, 253505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, D.J.; Jiangang, D.; Zorman, C.A.; Ko, W.H. High-temperature single-crystal 3C-SiC capacitive pressure sensor. IEEE Sens. J. 2004, 4, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziermann, R.; Berg, J.v.; Reichert, W.; Obermeier, E.; Eickhoff, M.; Krotz, G. A high temperature pressure sensor with /spl beta/-SiC piezoresistors on SOI substrates. In Proceedings of the International Solid State Sensors and Actuators Conference (Transducers ‘97), Chicago, IL, USA, 16–19 June 1997; Volume 1412, pp. 1411–1414. [Google Scholar]

- Okojie, R.S.; Ned, A.A.; Kurtz, A.D. Operation of α(6H)-SiC pressure sensor at 500 °C. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 1998, 66, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koley, G.; Prio, M.H.; Bayram, F.; Gajula, D. III-Nitrides for sensing at high temperatures. In Proceedings of the NAECON 2024—IEEE National Aerospace and Electronics Conference, Dayton, OH, USA, 15–18 July 2024; pp. 301–305. [Google Scholar]

- Lalinský, T.; Hudek, P.; Vanko, G.; Dzuba, J.; Kutiš, V.; Srnánek, R.; Kostič, I. Micromachined membrane structures for pressure sensors based on AlGaN/GaN circular HEMT sensing device. Microelectron. Eng. 2012, 98, 578–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Chen, Y.Q.; Liu, C.; He, Z.; Chen, Y.; Geng, K.W. Temperature-Dependent Electrical Characteristics and Low-Frequency Noise Analysis of AlGaN/GaN HEMTs. IEEE J. Electron Devices Soc. 2024, 12, 698–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambacher, O.; Smart, J.; Shealy, J.R.; Weimann, N.G.; Chu, K.; Murphy, M.; Schaff, W.J.; Eastman, L.F.; Dimitory, R.; Wittmer, L.; et al. Two-dimensional electron gases induced by spontaneous and piezoelectric polarization charges in N-and Ga-face AlGaN/GaN heterostructures. J. Appl. Phys. 1999, 85, 3222–3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambacher, O. Growth and applications of group III-nitrides. J. Phys. D 1998, 31, 2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardini, F.; Fiorentini, V.; Vanderbilt, D. Spontaneous polarization and piezoelectric constants of III-V nitrides. Phys. Rev. B 1997, 56, R10024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koley, G.; Cha, H.-Y.; Hwang, J.; Schaff, W.J.; Eastman, L.F.; Spencer, M.G. Perturbation of charges in AlGaN/GaN heterostructures by ultraviolet laser illumination. J. Appl. Phys. 2004, 96, 4253–4262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koley, G.; Spencer, M. On the origin of the two-dimensional electron gas at the AlGaN/GaN heterostructure interface. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2005, 86, 042107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambacher, O.; Foutz, B.; Smart, J.; Shealy, J.R.; Weimann, N.G.; Chu, K.; Murphy, M.; Sierakowski, A.J.; Schaff, W.J.; Eastman, L.F.; et al. Two-dimensional electron gases induced by spontaneous and piezoelectric polarization in undoped and doped AlGaN/GaN heterostructures. J. Appl. Phys. 2000, 87, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazi, M.; DeRoller, N.; Talukdar, A.; Koley, G. III-V Nitride based piezoresistive microcantilever for sensing applications. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 99, 193508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casans, S.; Munoz, D.R.; Navarro, A.E.; Salazar, A. ISFET drawbacks minimization using a novel electronic compensation. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2004, 99, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casans, S.; Navarro, A.E.; Ramirez, D.; Pelegri, D.; Baldi, A.; Abramova, N. Novel constant current driver for ISFET/MEMFETs characterization. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2001, 76, 629–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, F.; Montealegre, E.; Aranel, J.; Paredes, D.; Ramirez, G.; Chung, W.-Y. ISFET Bridge Type Readout Circuit with Programmable Voltage and Current. In Proceedings of the TENCON 2018—2018 IEEE Region 10 Conference, Jeju, Republic of Korea, 28–31 October 2018; pp. 2362–2365. [Google Scholar]

- Talukdar, A.; Khan, M.F.; Lee, D.; Kim, S.; Thundt, T.; Koley, G. Piezotransistive transduction of femtoscale displacement for photoacoustic spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzuba, J.; Kordoš, P.; Gregušová, D.; Kováč, J.; Donoval, D.; Vanko, G. Stress Investigation of the AlGaN/GaN Micromachined Circular Diaphragms of a Pressure Sensor. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2015, 25, 015001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furqan, C.M.; Khan, M.U.; Awais, M.; Jiang, F.; Bae, J.; Hassan, A.; Kwok, H.-S. Humidity Sensor Based on Gallium Nitride for Real Time Monitoring Applications. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, M.; Pradhan, M.; Alomari, M.; Burghartz, J.N. Model and Simulation of GaN-Based Pressure Sensors for High Temperature Applications—Part II: Sensor Design and Simulation. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 20176–20183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koley, G.; Tilak, V.; Eastman, L.F.; Spencer, M.G. Slow Transients Observed in AlGaN/GaN HFETs: Effects of SiNx Passivation and UV Illumination. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2003, 50, 886–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omega High Accuracy PX409 Series Pressure Transducers. Available online: https://sea.omega.com/ph/pptst/PX409_Series.html (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- PCB Piezotronics Model 121A45 Intrinsic Safe ICP Pressure Sensor. Available online: https://www.pcb.com/products?m=121a45 (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Gunn, A.W.; Prio, M.H.; Gajula, D.; Koley, G. Sub-bandgap photon-assisted electron trapping and detrapping in AlGaN/GaN heterostructure field-effect transistors. Phys. Scr. 2023, 98, 065808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SMC Solenoid Valve Model VT307 Series. Available online: https://www.smcpneumatics.com/pdfs/VT307.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Tao, Y.Q.; Chen, D.J.; Kong, Y.C.; Shen, B.; Xie, Z.L.; Han, P.; Zhang, R.; Zheng, Y.D. High-temperature transport properties of 2DEG in AlGaN/GaN heterostructures. J. Electron. Mater. 2006, 35, 722–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Simulation Parameter (Unit) | GaN | AlGaN |

|---|---|---|

| Young’s Modulus (GPa) | 265 | 285 |

| Poisson’s Ratio | 0.183 | 0.3225 |

| Density (kg/m3) | 6095 | 3000 |

| Parameter | Calculated Value |

|---|---|

| 2DEG Density (ns) | 1.11 × 1013 cm−2 |

| Change in 2DEG Density (∆ns) | −4.6708 × 1010 cm−2 |

| ∆PPE(bending) | −5.89 × 10−9 cm−2 |

| Simulation Parameter (Unit) | RT | 300 °C |

|---|---|---|

| Contact Resistance, Rc | 8.69 Ω | 11.24 Ω |

| Sheet Resistance, RS | 284.49 Ω/□ | 634.63 Ω/□ |

| Transfer Length, LT | 3.05 µm | 1.77 µm |

| Specific Contact Resistivity, ρc | 2.65 × 10−5 Ωcm−2 | 1.99 × 10−5 Ωcm−2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Prio, M.H.; Morshed, M.; Muthusamy, L.; Raju, M.S.E.H.; Towfeeq, I.; Gajula, D.; Koley, G. Investigation of III-Nitride MEMS Pressure Sensor for High-Temperature Applications. Micromachines 2026, 17, 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17020177

Prio MH, Morshed M, Muthusamy L, Raju MSEH, Towfeeq I, Gajula D, Koley G. Investigation of III-Nitride MEMS Pressure Sensor for High-Temperature Applications. Micromachines. 2026; 17(2):177. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17020177

Chicago/Turabian StylePrio, Makhluk Hossain, Maruf Morshed, Lavanya Muthusamy, Md Sohanur E. Hijrat Raju, Itmenon Towfeeq, Durga Gajula, and Goutam Koley. 2026. "Investigation of III-Nitride MEMS Pressure Sensor for High-Temperature Applications" Micromachines 17, no. 2: 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17020177

APA StylePrio, M. H., Morshed, M., Muthusamy, L., Raju, M. S. E. H., Towfeeq, I., Gajula, D., & Koley, G. (2026). Investigation of III-Nitride MEMS Pressure Sensor for High-Temperature Applications. Micromachines, 17(2), 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17020177