Optimization Method for the Synergistic Control of DRIE Process Parameters on Sidewall Steepness and Aspect Ratio

Abstract

1. Introduction

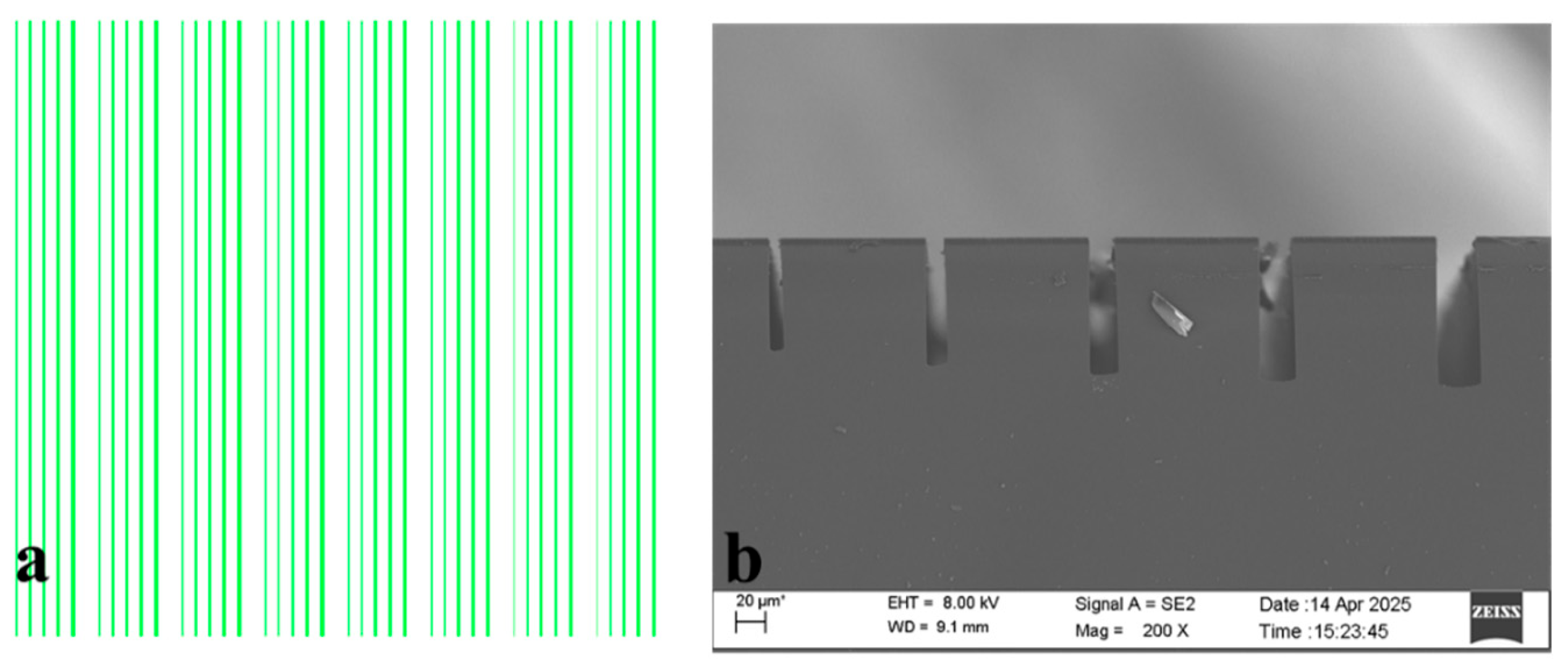

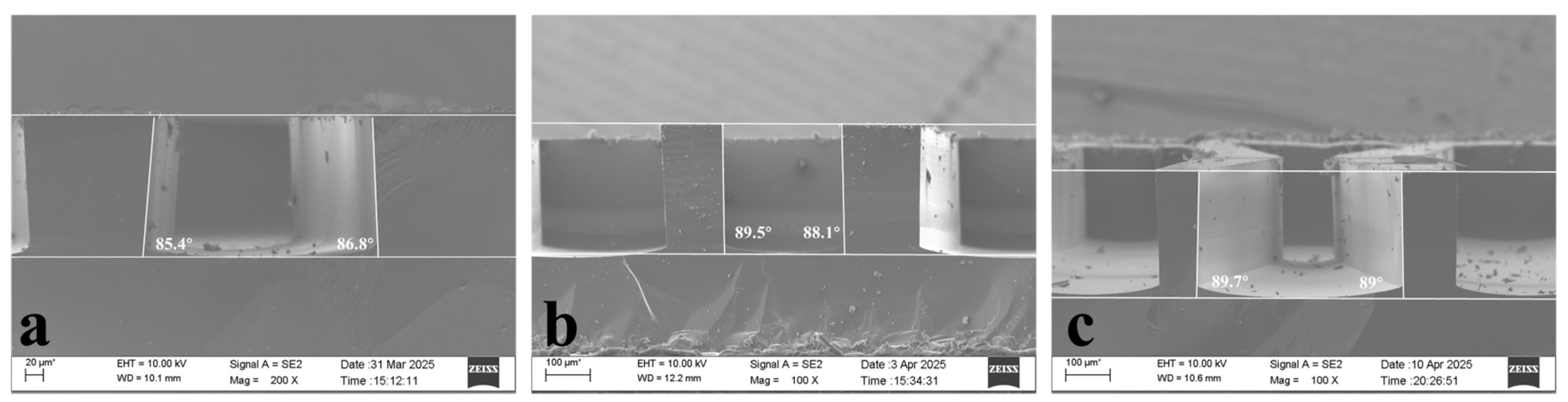

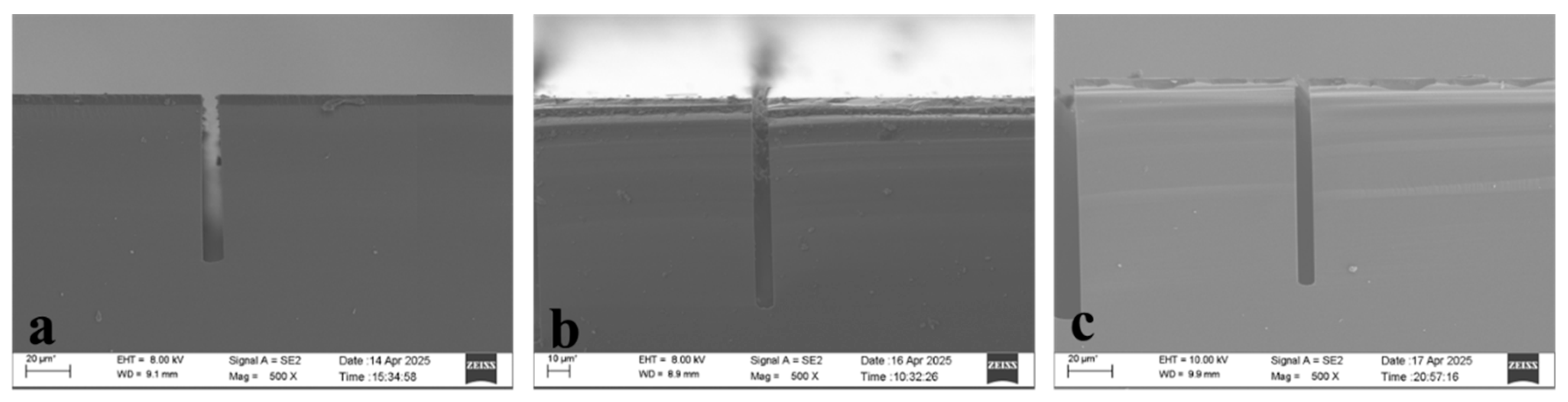

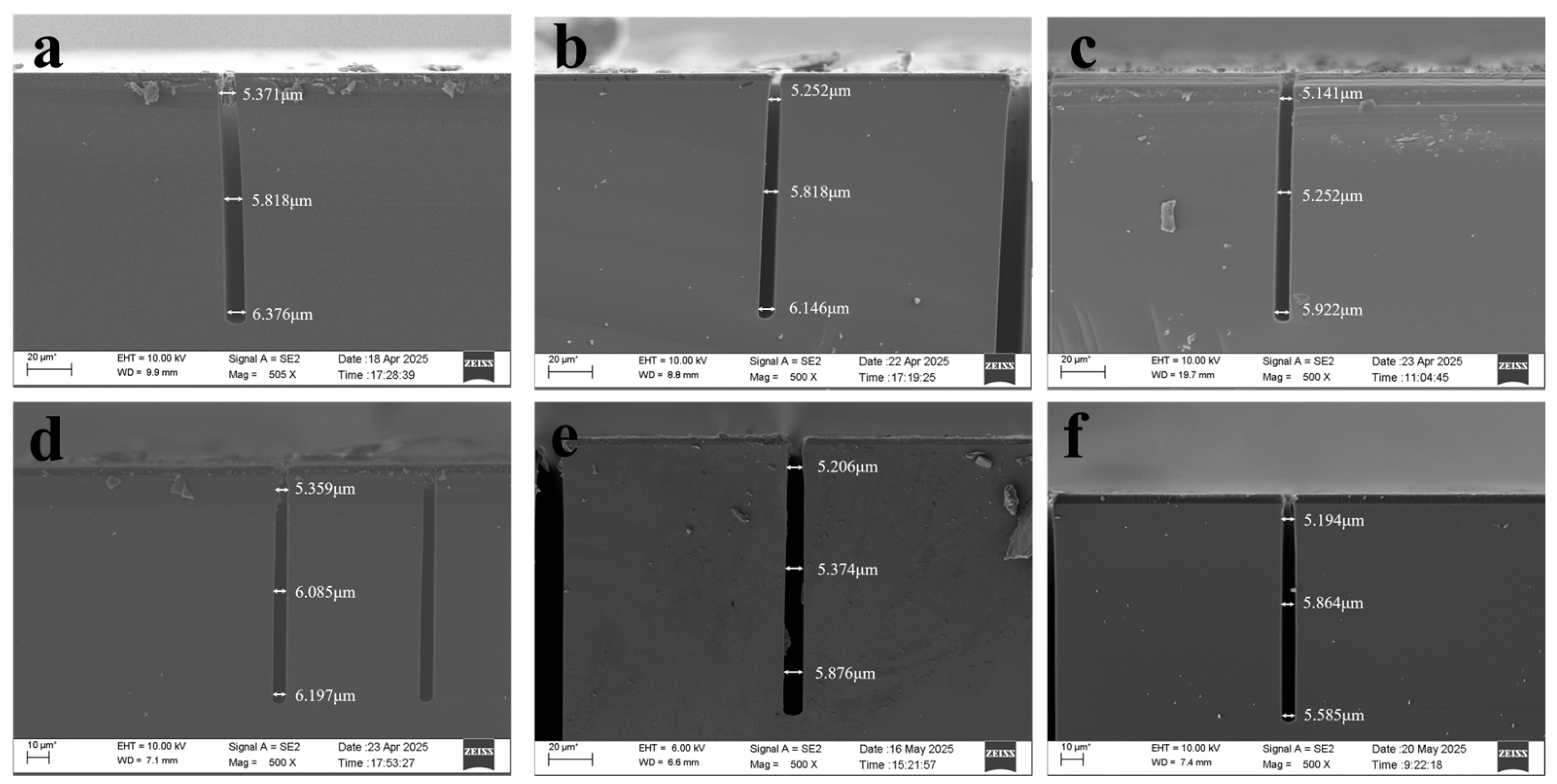

2. Materials and Methods

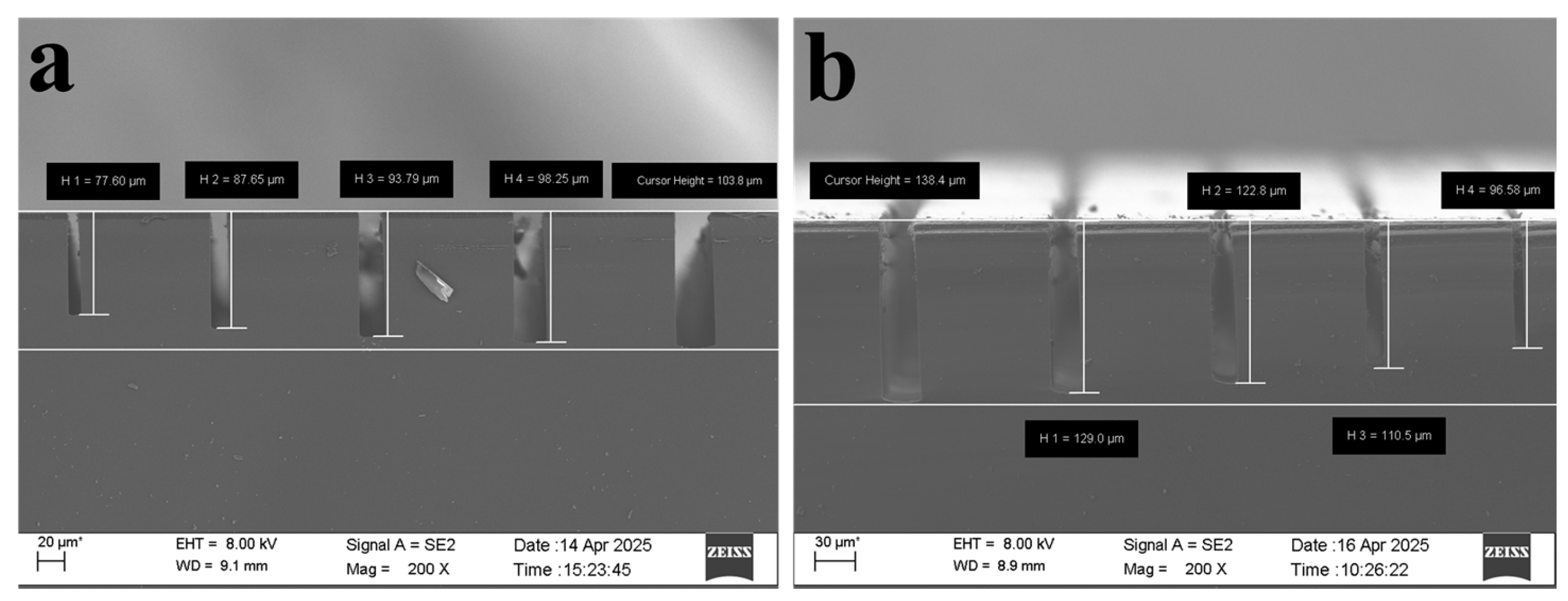

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Park, J.S.; Kang, D.H.; Kwak, S.M.; Kim, T.S.; Park, J.H.; Kim, T.G.; Baek, S.-H.; Lee, B.C. Low-temperature smoothing method of scalloped DRIE trench by post-dry etching process based on SF6 plasma. Micro Nano Syst. Lett. 2020, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, D.; Hong, S.; Lee, M.; Kim, T. A review of silicon microfabricated ion traps for quantum information processing. Micro Nano Syst. Lett. 2015, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H. Formation mechanism of multi-functional black silicon based on optimized deep reactive ion etching technique with SF6/C4F8. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2015, 58, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Lee, J. Optimization of deep reactive ion etching for microscale silicon hole arrays with high aspect ratio. Micro Nano Syst. Lett. 2022, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Yi, R.; Ding, X.; Chiu, T.; He, Q.; Deng, H. Surface evolution mechanism for atomic-scale smoothing of Si via atmospheric pressure plasma etching. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 132, 132353–132362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhu, C.; Lin, G.; Lin, Y. Deep silicon etching technology and applications: A review. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2025, 35, 083001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Ylinen, S.; Kainlauri, M.; Kapulainen, M. Smooth silicon sidewall etching for waveguide structures using a modified Bosch process. J. Micro/Nanolithogr. MEMS MOEMS 2014, 13, 013010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugaya, T.; Yoon, D.H.; Yamazaki, H.; Nakanishi, K.; Sekiguchi, T.; Shoji, S. Simple and Rapid Fabrication Process of Porous Silicon Surface Using Inductively Coupled Plasma Reactive Ion Etching. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 2020, 29, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golishnikov, A.A.; Dyuzhev, N.A.; Paramonov, V.V.; Potapenko, I.V.; Putrya, M.G.; Somov, N.M.; Chaplygin, Y.A. Research and Development of a Deep Anisotropic Silicon Plasma Etching Process with Reduced Sidewall Roughness of the Structures. Russ. Microelectron. 2025, 53, 676–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Guo, J.; Fan, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, J.; Ye, S. Sub-200-nm-diameter cylindrical silicon nanopillars with high aspect ratio (40:1) fabricated by SF6/C4F8-modulated ICP-RIE. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2025, 198, 198109817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakrathok, A.; Supadech, J.; Leepattarapongpan, C.; Paosangthong, W.; Atthi, N.; Jeamsaksiri, W.; Kobdaj, C. Design of the comb-drive structure to reduce asymmetry lateral plasma etching on the cavity SOI substrate for MEMS fabrication. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2025, 2934, 012027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Gao, Z.; Fang, Y.; Cen, D.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, C.; Zhao, E.; Zhu, W.; Wu, W.; et al. Research on the difference in etching rates of SiO2 at the top and bottom of a high-aspect-ratio trench in C4F8/Ar/O2 plasma etching. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2025, 43, 033003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Jefimovs, K.; Romano, L.; Stampanoni, M. Towards the Fabrication of High-Aspect-Ratio Silicon Gratings by Deep Reactive Ion Etching. Micromachines 2020, 11, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Sandoughsaz, A.; Owen, K.J.; Najafi, K. Ultra Deep Reactive Ion Etching of High Aspect-Ratio and Thick Silicon Using a Ramped-Parameter Process. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 2018, 27, 686–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Cao, S.; Li, L.; Zhang, X. A review on the mainstream through-silicon via etching methods. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2022, 137, 106182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrantes, A.A.J.; Mastrangeli, M.; Thoen, D.J.; Visser, S.; Bueno, J.; Baselmans, J.J.A.; Sarro, P.M. Superconducting High-Aspect Ratio Through-Silicon Vias with DC-Sputtered Al for Quantum 3D integration. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2020, 41, 1114–1117. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Z.; Ma, Z.; Gao, L.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Hao, Y.; Deng, Y. Etching mechanism of high-aspect-ratio array structure. Microelectron. Eng. 2023, 279, 112060. [Google Scholar]

- Alfaro-Barrantes, J.A.; Mastrangeli, M.; Thoen, D.J.; Bueno, J.; Baselmans, J.J.; Sarro, P.M. Fabrication of Al-Based Superconducting High-Aspect Ratio TSVS for Quantum 3D Integration. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 January 2020; pp. 932–935. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, Z.-H.; Xia, Y.; Hu, C.; Xu, Q.; Qiu, L.-N.; Qu, X.-P. Metallization filling and electrical performance of high-aspect-ratio through silicon via with electroless deposited Co liner. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2025, 14, 054003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Smith, D.; Kumarapuram, G.; Giridharan, R.; Kakita, S.; Rabie, M.A.; Feng, P.; Edmundson, H.; England, L. Process development and optimization for 3 μm high aspect ratio via-middle through-silicon vias at wafer level. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2015, 28, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, A.; Samaan, M.; Yan, Z.; Hu, W.; Cui, B. Fabrication of ultrahigh aspect ratio Si nanopillar and nanocone arrays. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 2023, 41, 023001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, T.; Takahashi, K.; Uchida, A.; Tsuji, O. Morphology of films deposited on the sidewall during the Bosch process using C4F8 plasmas. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2024, 34, 085014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, T.; Takahashi, K.; Uchida, A.; Lundgaard, S.; Tsuji, O. Effects of C4F8 plasma polymerization film on etching profiles in the Bosch process. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2023, 41, 063004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, R.L.; Stephan Thamban, P.L.; Goeckner, M.J.; Overzet, L. Silicon etch using SF6/C4F8/Ar gas mixtures. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A Vac. Surf. Film. 2014, 32, 041302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nos, J.; Iséni, S.; Kogelschatz, M.; Cunge, G.; Lefaucheux, P.; Dussart, R.; Tillocher, T.; Despiau-Pujo, É. Cryogenic cyclical etching of Si using CF4 plasma passivation steps: The role of CF radicals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2025, 126, 031602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, S.; Belen, R.J.; Kiehlbauch, M.; Aydil, E.S. Etching of high aspect ratio structures in Si using SF6/O2 plasma. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A. Vac. Surf. Film. 2004, 22, 606–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-P.; Kim, K.-S.; Jeong, J.-C. Effects of RF Power Source and PR Pattern Size on Sidewall Surface of Deep Silicon Via during DRIE Process. Trans. Korean Inst. Electr. Eng. 2021, 71, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishchuk, V.; Volland, B.E.; Hauguth, M.; Cooke, M.; Rangelow, I.W. Charging effect simulation model used in simulations of plasma etching of silicon. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 112, 084308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

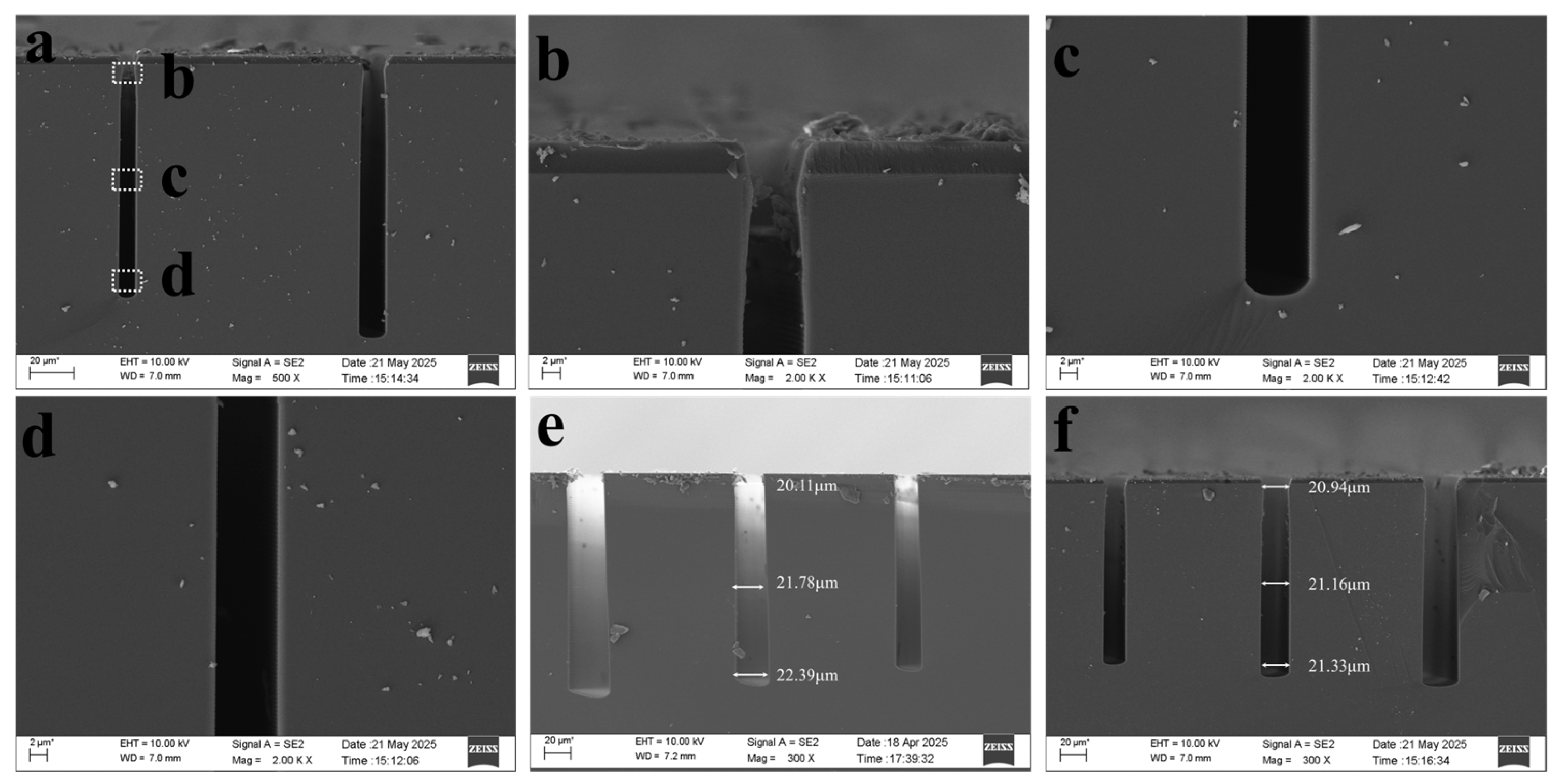

| Parameters | Cycles | Time/s | Center C4F8/sccm | Edge C4F8/sccm | Center SF6/sccm | Edge SF6/sccm | LFPower/W |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dep | 100 | 1.5 | 180 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Etch1 | 100 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 300 | 300 | 100 |

| Etch2 | 100 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 300 | 300 | 40 |

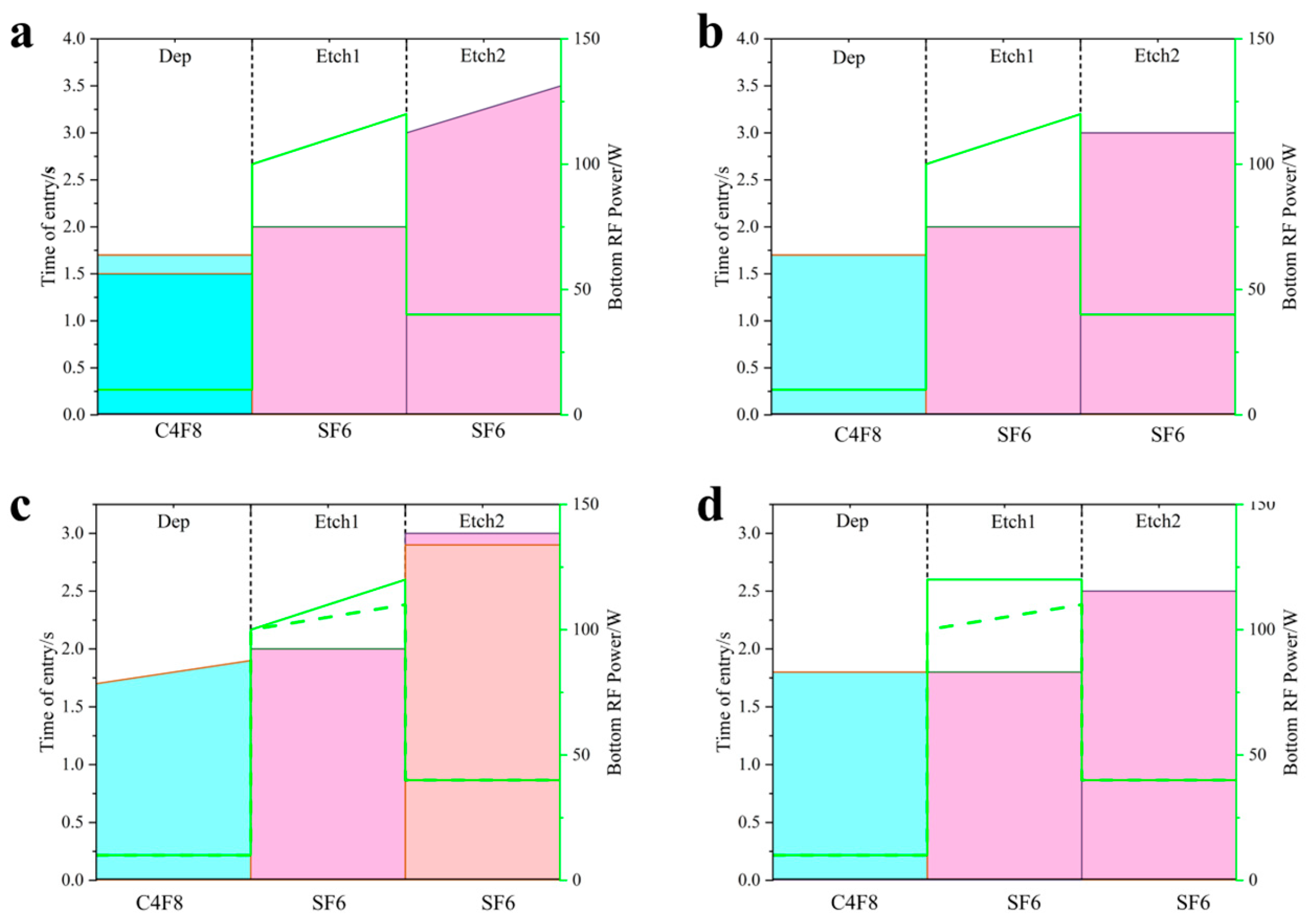

| Parameters | Cycles | Time (s) | Center C4F8/sccm | Edge C4F8/sccm | LFPower | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Dep | 100→150→180 | 1.5 | 180 | 0 | 10 |

| Etch1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 100 | ||

| Etch2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 40 | ||

| B | Dep | 180 | 1.5/1.5→1.7 | 180 | 0 | 10 |

| Etch1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 100–120/100–110 | ||

| Etch2 | 3–3.5/3–3.2 | 0 | 0 | 40 | ||

| C | Dep | 180 | 1.7/1.7–1.9 | 180 | 50 | 10 |

| Etch1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 100–110→100–120 | ||

| Etch2 | 2.9→3 | 0 | 0 | 40 | ||

| D | Dep | 200 | 1.8 | 180 | 50 | 10 |

| Etch1 | 1.8 | 0 | 0 | 100–100→120 | ||

| Etch2 | 2.5 | 0 | 0 | 40 |

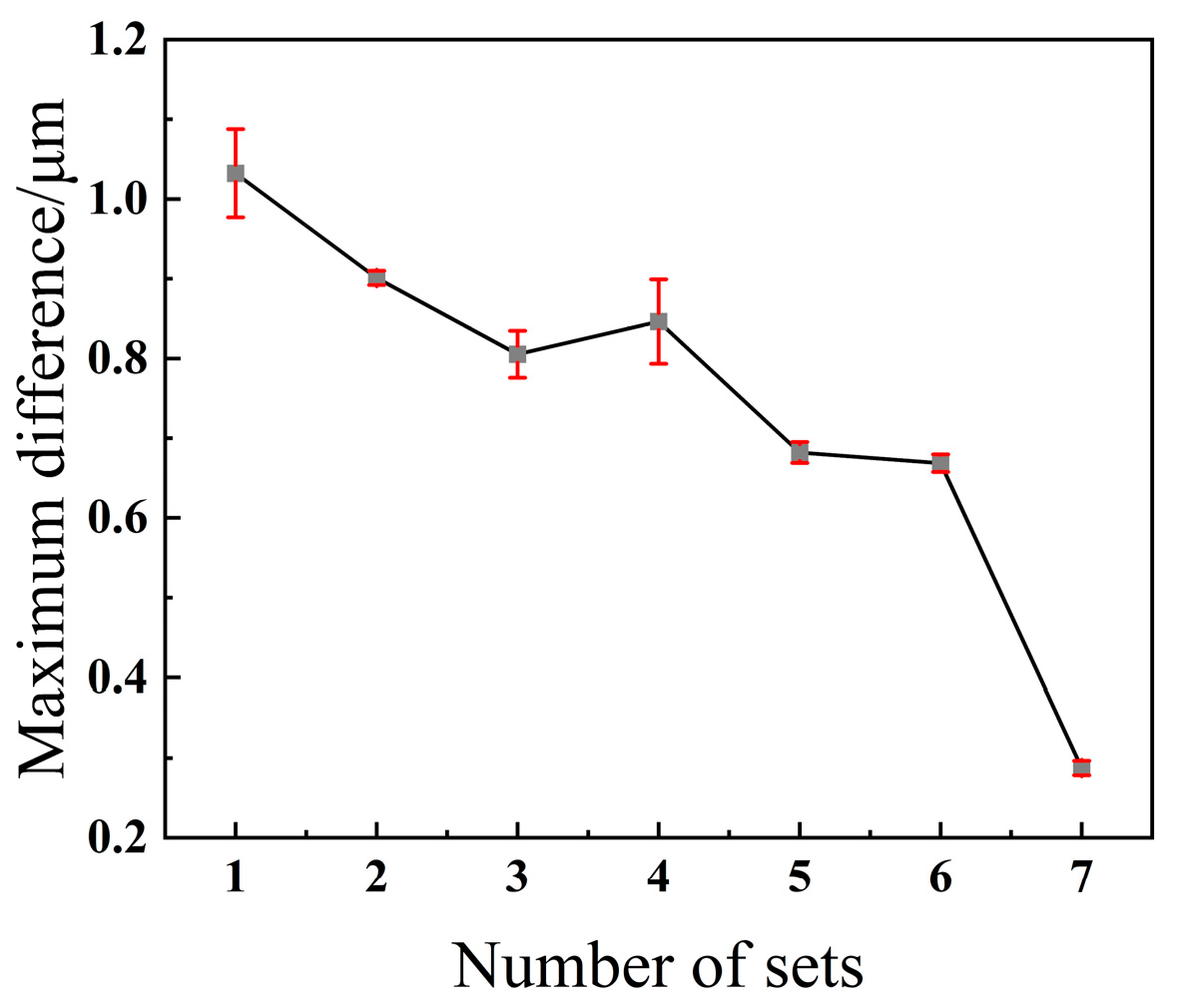

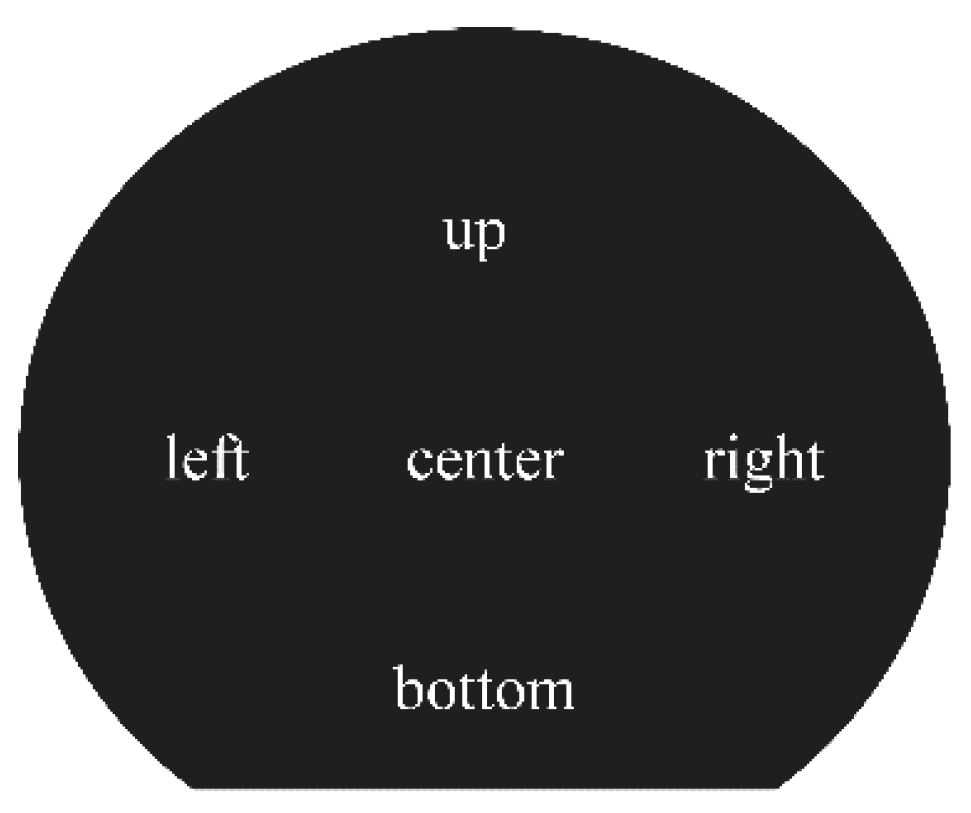

| Position | Etch Depth/μm | Opening Size Difference/μm |

|---|---|---|

| center | 106.662 | 0.279 |

| up | 106.1 | 0.279 |

| bottom | 108.3 | 0.335 |

| left | 109.427 | 0.340 |

| right | 108.3 | 0.340 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, D.; Lei, C.; Ji, P.; Li, Z.; Yuan, R.; Yu, J.; Liang, T.; Yao, Z.; Li, J. Optimization Method for the Synergistic Control of DRIE Process Parameters on Sidewall Steepness and Aspect Ratio. Micromachines 2026, 17, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010013

Wang D, Lei C, Ji P, Li Z, Yuan R, Yu J, Liang T, Yao Z, Li J. Optimization Method for the Synergistic Control of DRIE Process Parameters on Sidewall Steepness and Aspect Ratio. Micromachines. 2026; 17(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Dandan, Cheng Lei, Pengfei Ji, Zhiqiang Li, Renzhi Yuan, Jiangang Yu, Ting Liang, Zong Yao, and Jialong Li. 2026. "Optimization Method for the Synergistic Control of DRIE Process Parameters on Sidewall Steepness and Aspect Ratio" Micromachines 17, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010013

APA StyleWang, D., Lei, C., Ji, P., Li, Z., Yuan, R., Yu, J., Liang, T., Yao, Z., & Li, J. (2026). Optimization Method for the Synergistic Control of DRIE Process Parameters on Sidewall Steepness and Aspect Ratio. Micromachines, 17(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010013