High-Performance and Thermally Robust A1-Mode Lamb Wave Resonators on Bonded LiNbO3/SiC Membranes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Analysis

2.1. Analysis Models

2.2. Effect of Rotated Y-Cut LN Angle in LN/SiC Membrane Resonator

- (1)

- LN-single: hLN/2p = 0.10; hAl/2p = 4%; MR = 0.50,

- (2)

- LN/SiC: hLN/2p = 0.10; hSiC/2p = 0.10; hAl/2p = 4%; MR = 0.50.

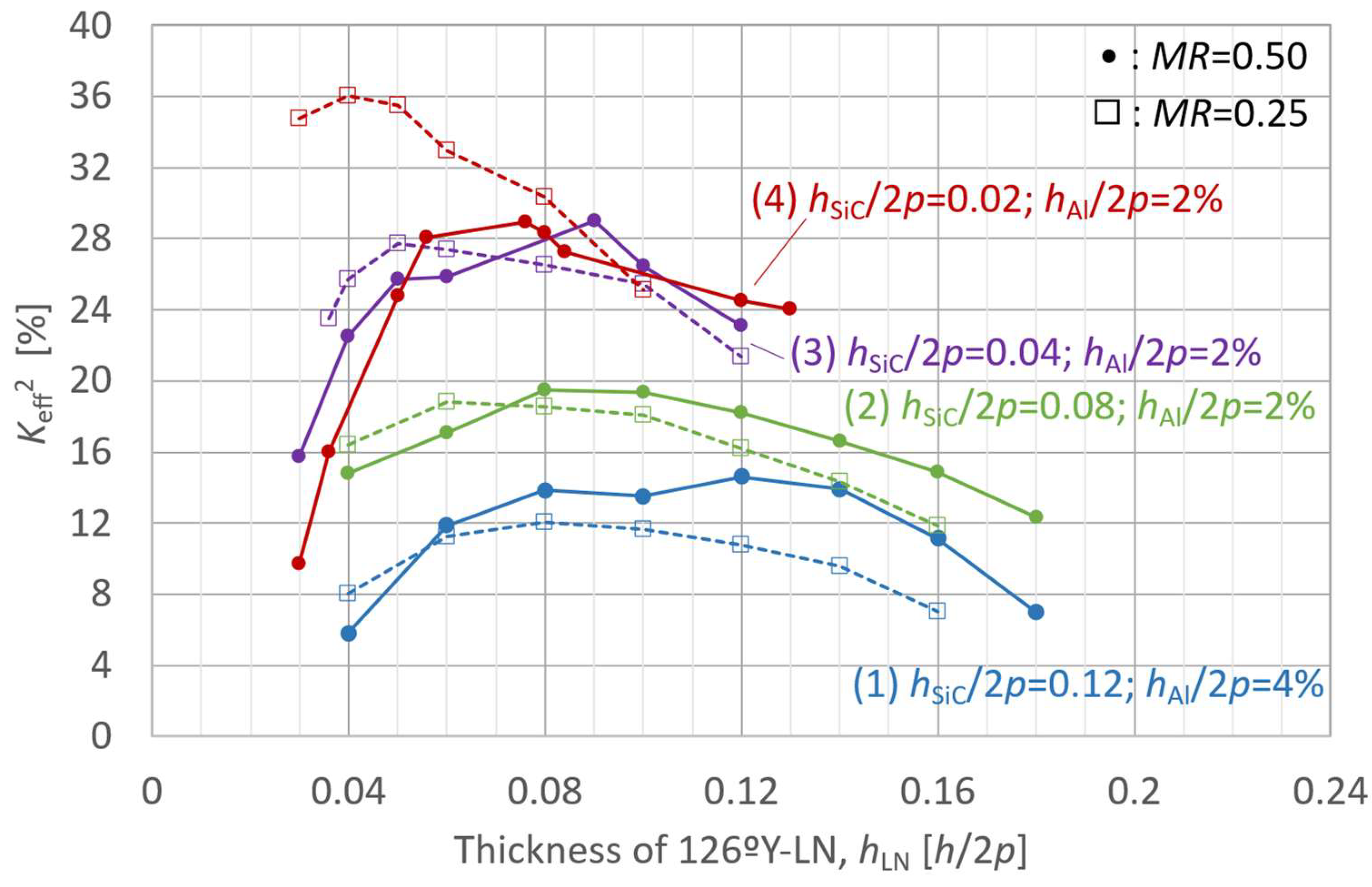

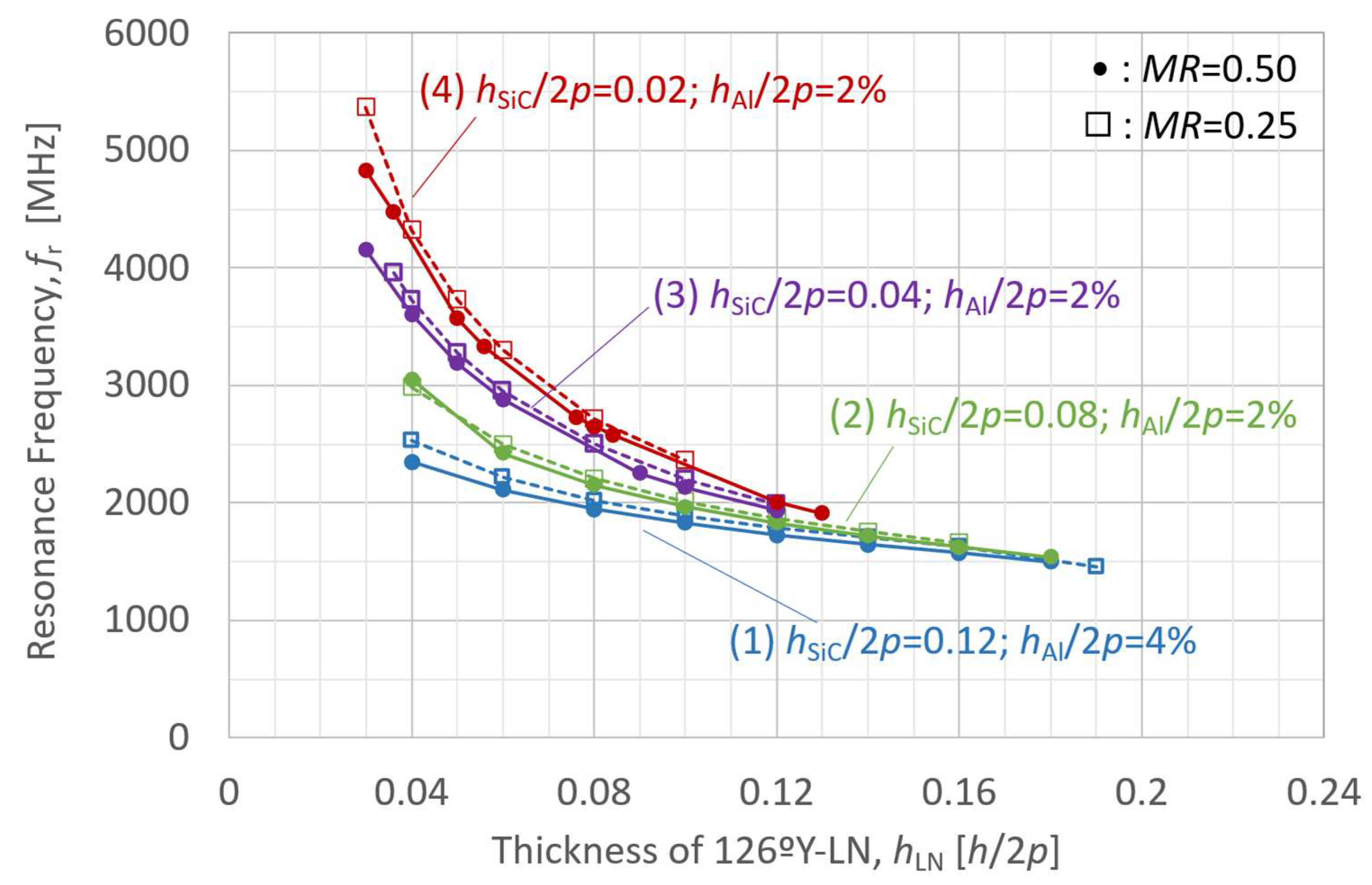

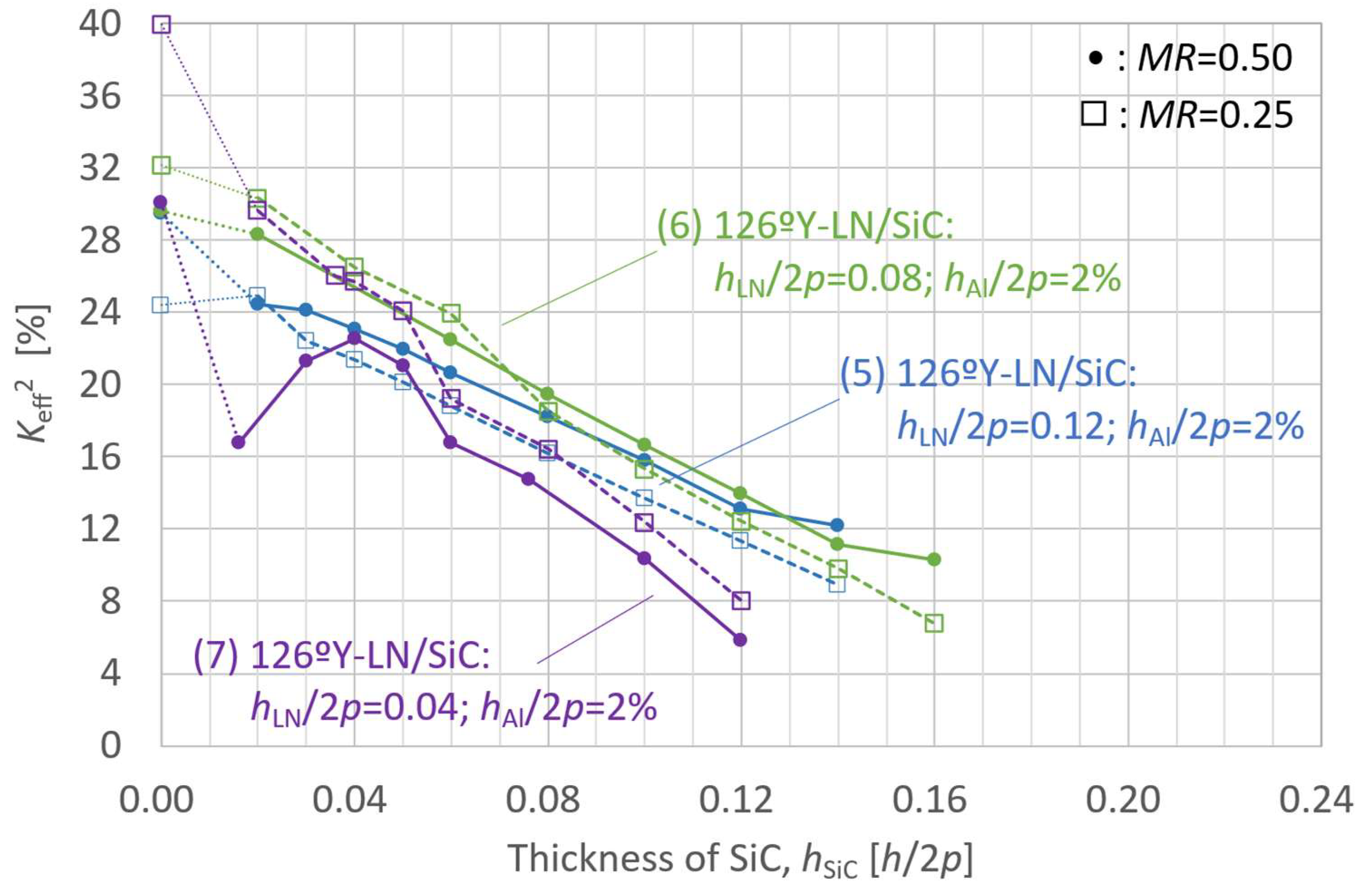

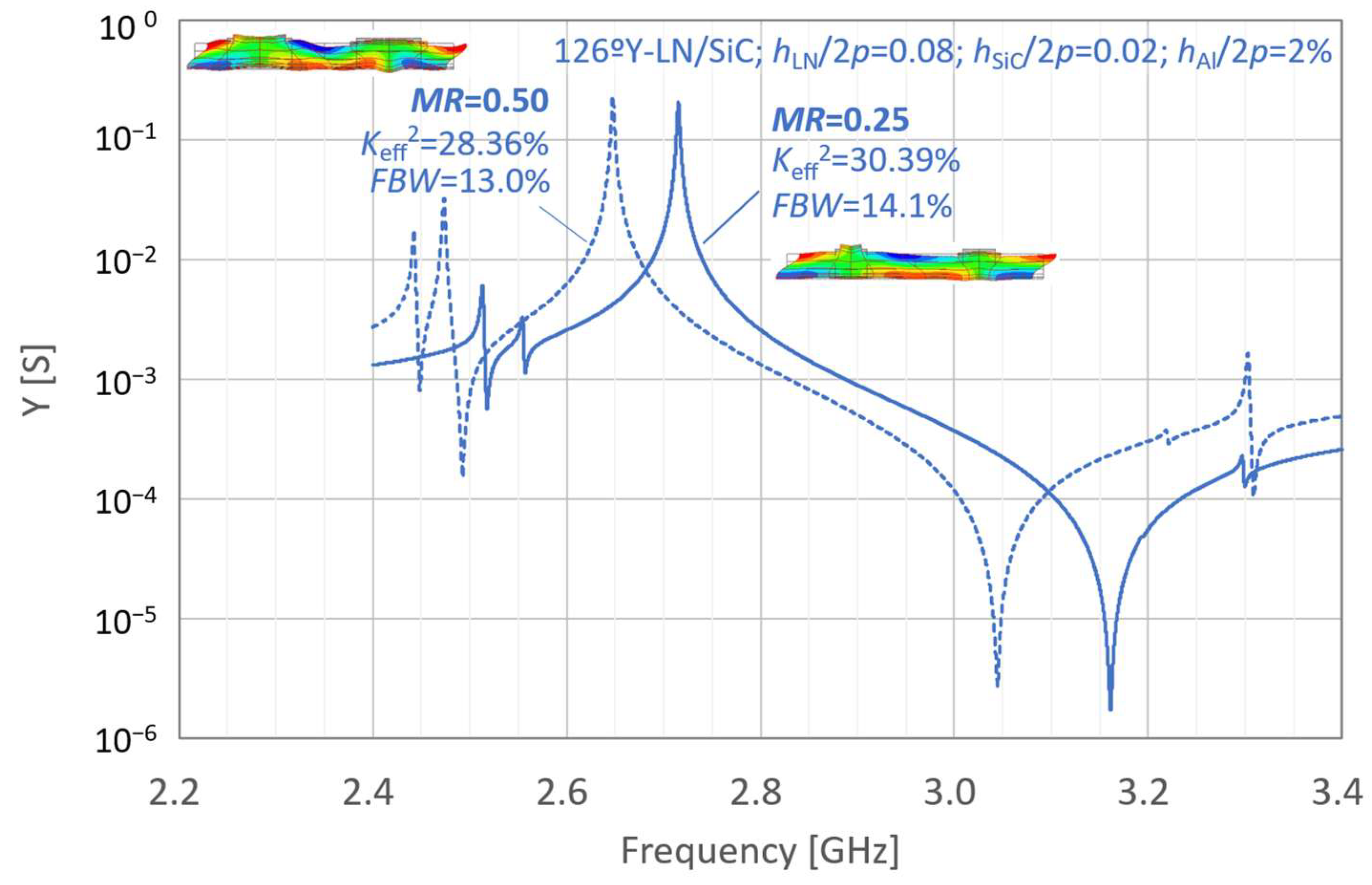

2.3. Effect of Layer Thickness in the LN/SiC Membrane Resonator

- (1)

- 126ºY-LN/SiC: hSiC/2p = 0.12; hAl/2p = 4%;

- (2)

- 126ºY-LN/SiC: hSiC/2p = 0.08; hAl/2p = 2%;

- (3)

- 126ºY-LN/SiC: hSiC/2p = 0.04; hAl/2p = 2%;

- (4)

- 126ºY-LN/SiC: hSiC/2p = 0.02; hAl/2p = 2%.

- (5)

- 126ºY-LN/SiC: hLN/2p = 0.12; hAl/2p = 2%;

- (6)

- 126ºY-LN/SiC: hLN/2p = 0.08; hAl/2p = 2%;

- (7)

- 126ºY-LN/SiC: hLN/2p = 0.04; hAl/2p = 2%.

2.4. Heat Conduction Analysis for the LN/SiC Membrane Structure

- 1—LN-single: hLN/2p = 0.10; hSiO2/2p = 0.10; hAl/2p = 4%; MR = 0.50

- 2—LN-single: hLN/2p = 0.10; hSiO2/2p = 0.10; hAl/2p = 4%; MR = 0.25

- 3—LN-single: hLN/2p = 0.16; hSiO2/2p = 0.10; hAl/2p = 4%; MR = 0.50

- 4—LN/SiC: hLN/2p = 0.10; hSiC/2p = 0.04; hAl/2p = 4%; MR = 0.50

- 5—LN/SiC: hLN/2p = 0.10; hSiC/2p = 0.04; hAl/2p = 4%; MR = 0.25

- 6—LN/SiC: hLN/2p = 0.10; hSiC/2p = 0.10; hAl/2p = 4%; MR = 0.50

- 7—LN/SiC: hLN/2p = 0.16; hSiC/2p = 0.10; hAl/2p = 4%; MR = 0.50

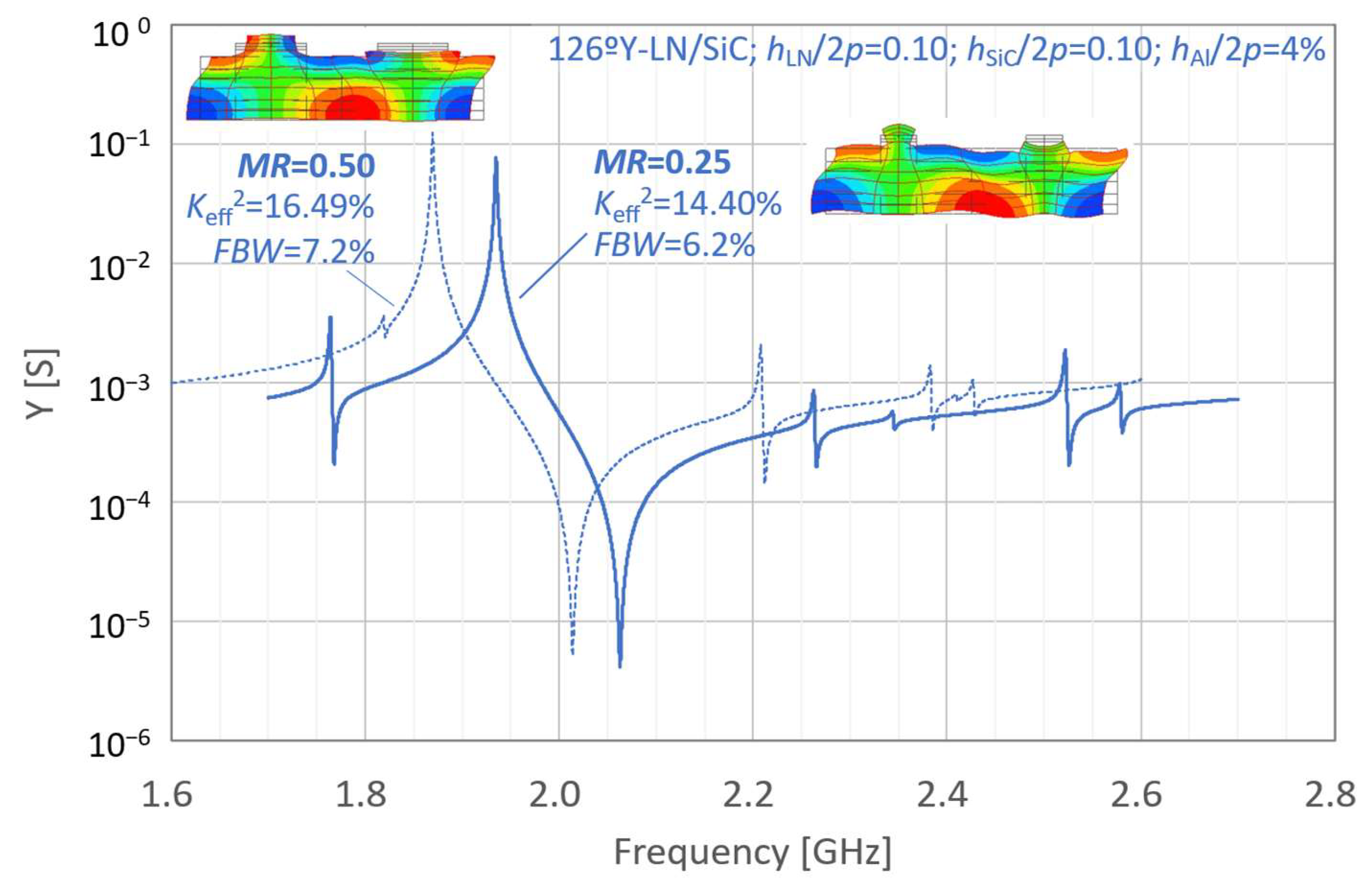

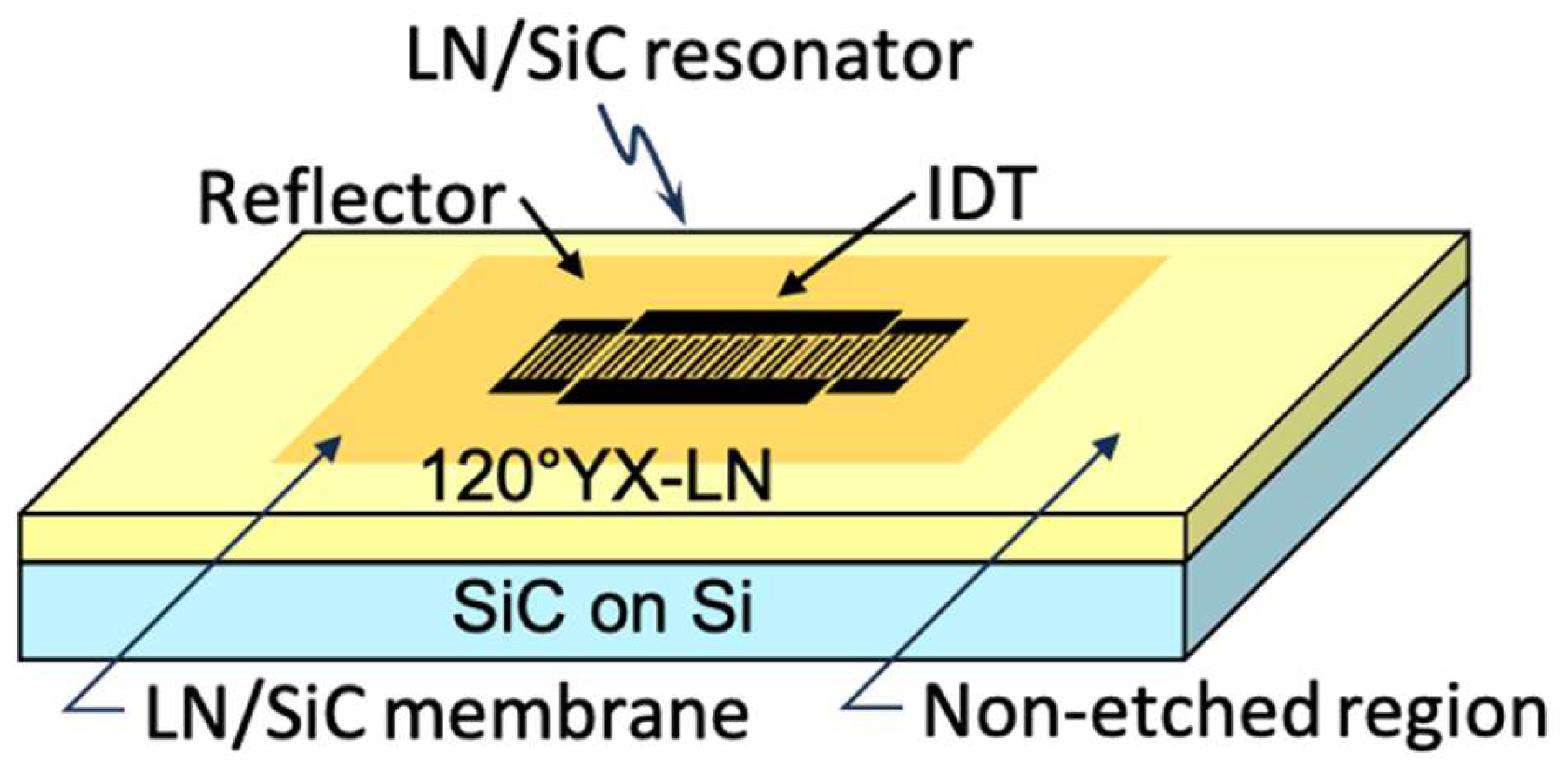

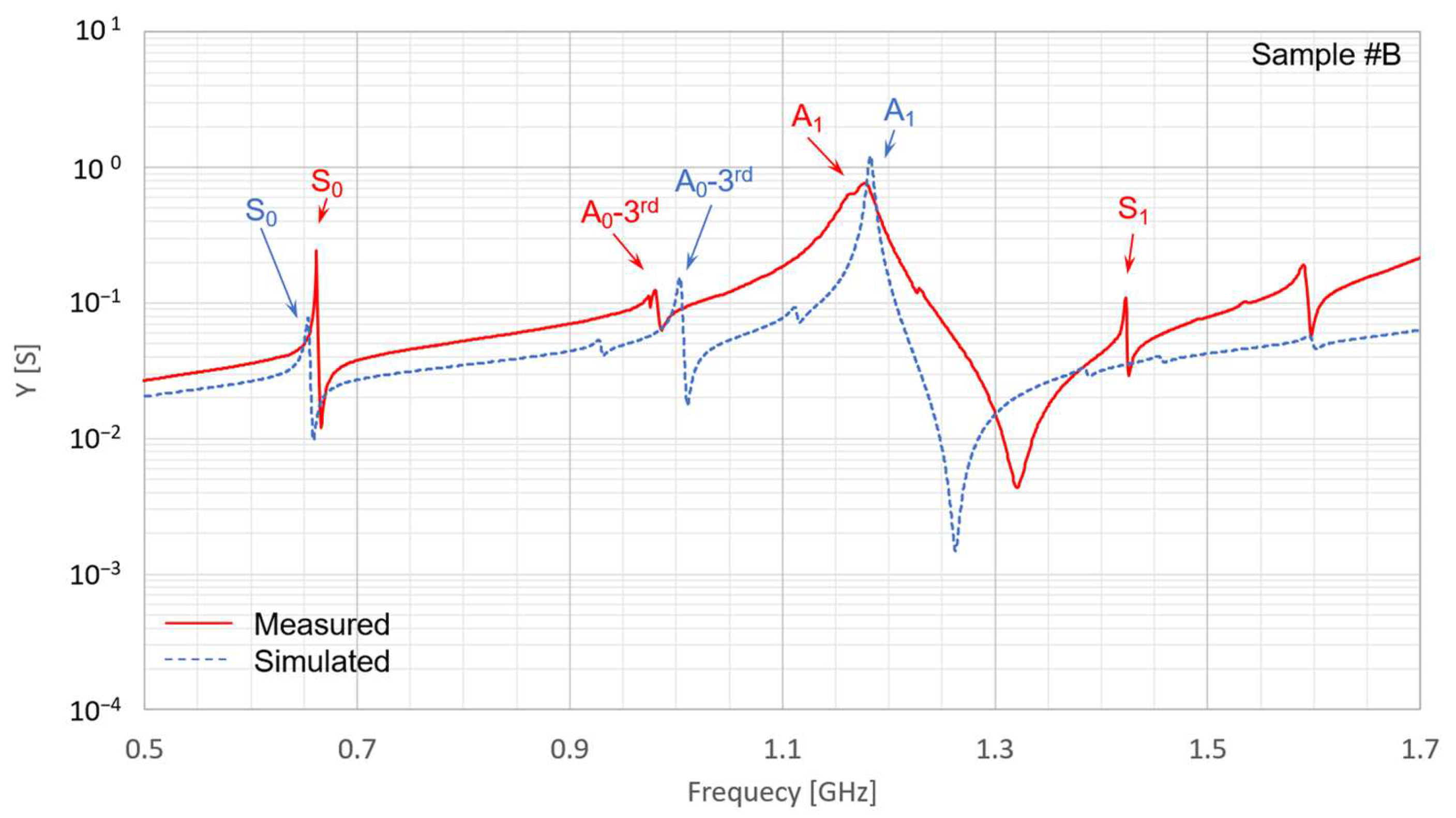

3. Experiments of LN/SiC Membrane Resonators

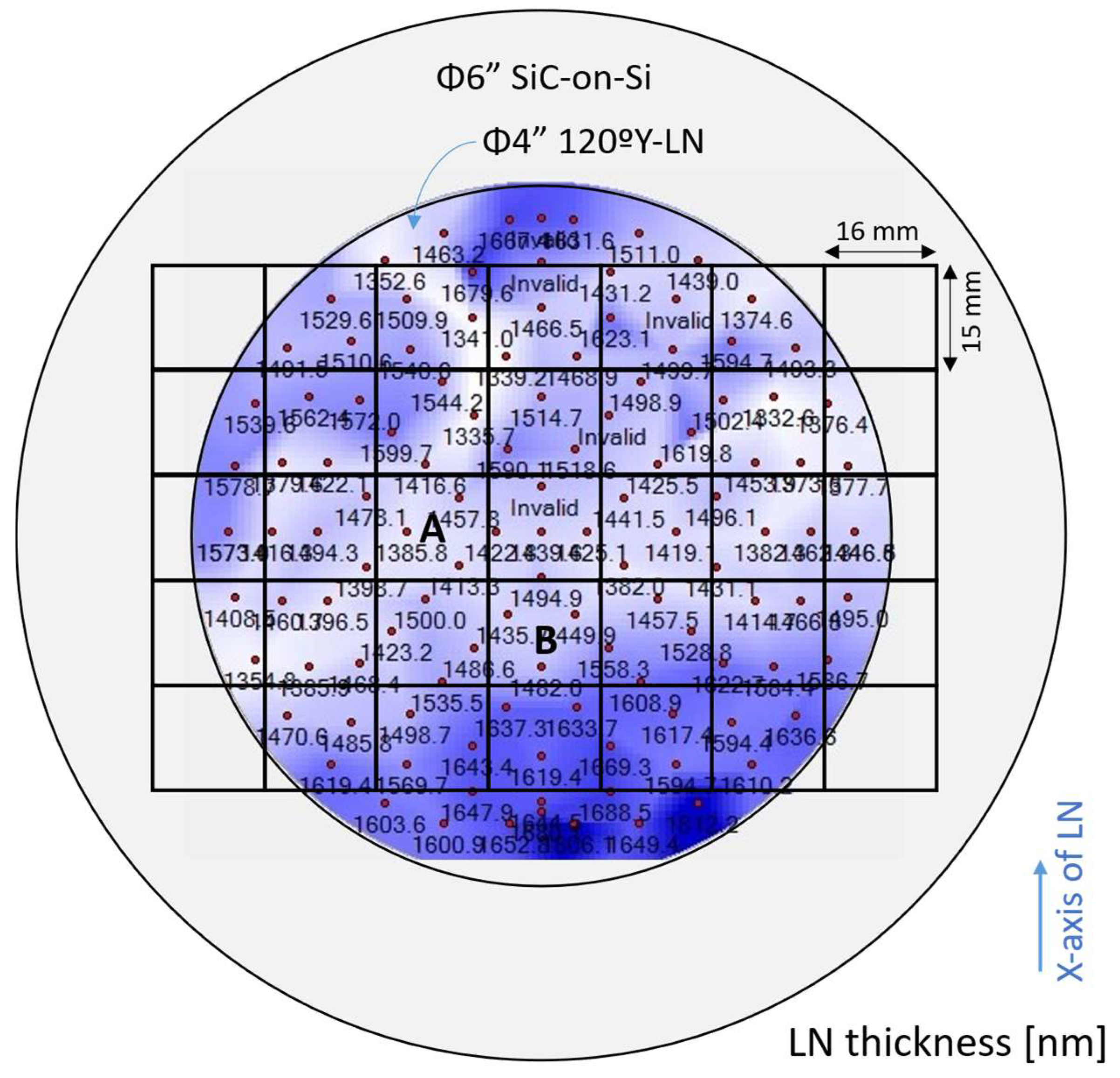

3.1. Prototype of LN/SiC-on-Si Substrate

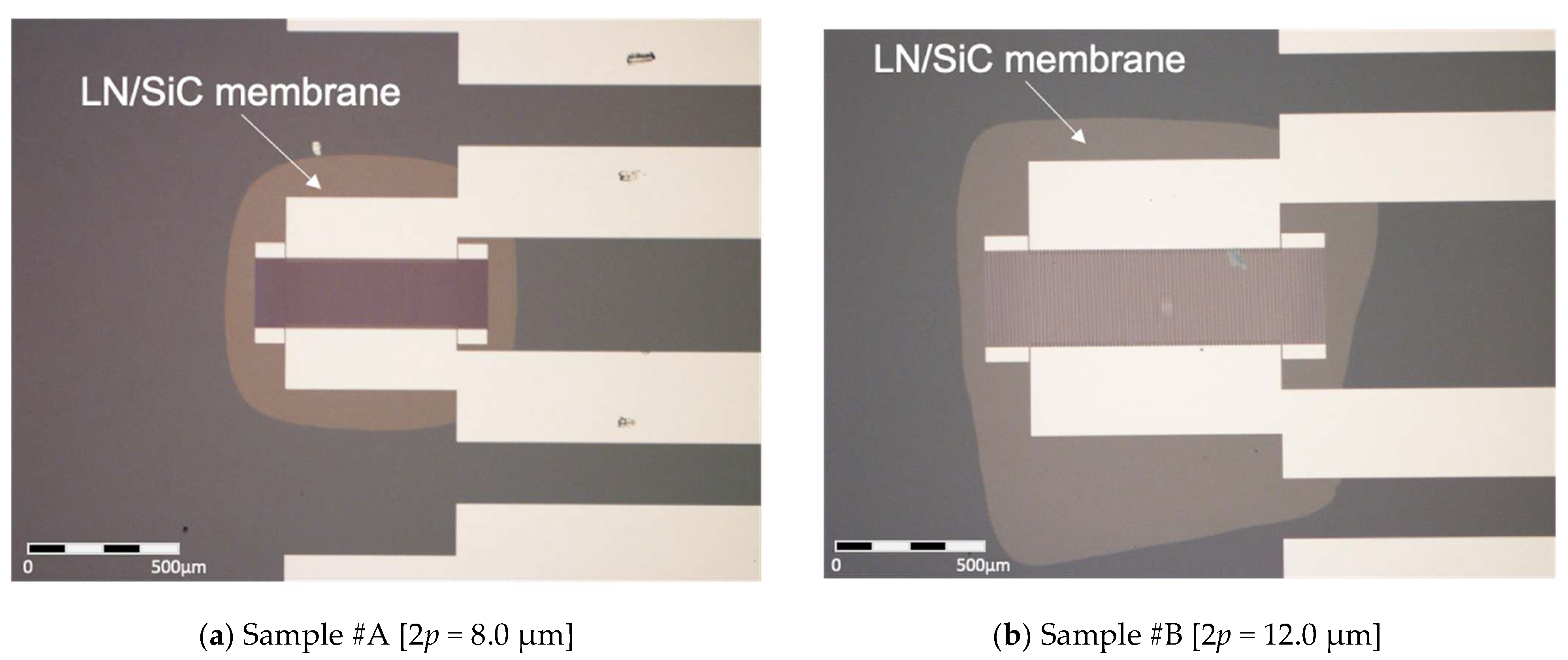

3.2. Fabrication of LN/SiC Membrane Resonators

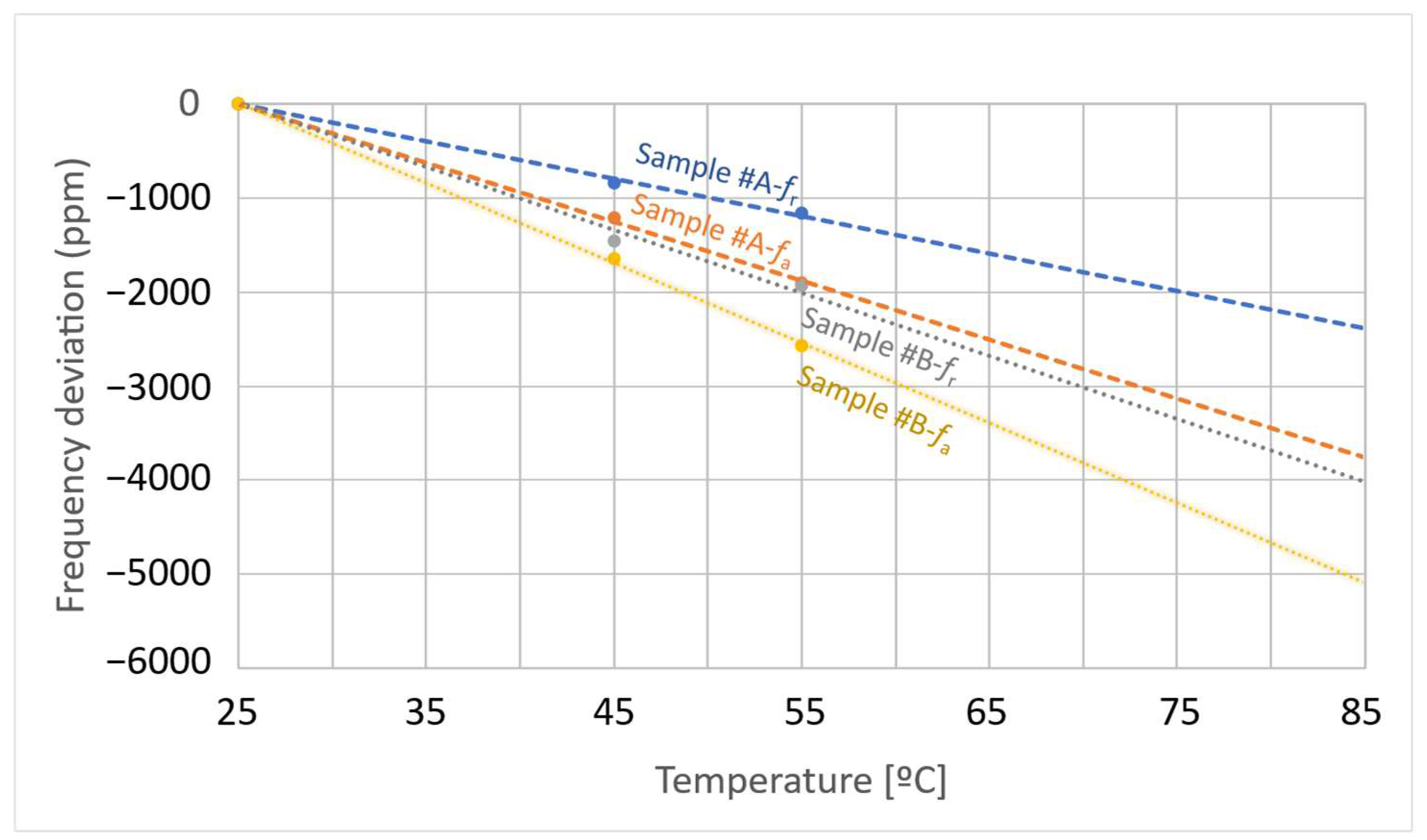

3.3. Measurements for the LN/SiC Membrane Resonators

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- FEM analysis revealed that the A1 mode in LN/SiC membrane resonators can achieve an extremely high Keff2 value up to approximately 30%, depending on design conditions. Experimental measurements yielded values of approximately 20%.

- (2)

- With the experimental layer configuration, a phase velocity Vp exceeding 14,000 m/s was obtained. The A1 mode in the LN/SiC membrane structure enables frequency tuning through the IDT pitch; for example, resonance frequencies of 1.76 GHz and 1.18 GHz were obtained for pitches of 2p = 8.0 µm and 2p = 12.0 µm, respectively.

- (3)

- Thermal conduction analysis demonstrated the effectiveness of the high thermal conductivity of SiC in the LN/SiC thin-membrane structure, significantly suppressing temperature rise within the resonator. Notably, even in the very thin-membrane configuration, the peak temperature increase remained as low as only 30–40 °C, in stark contrast to the nearly 300 °C rise observed in the LN-single structure, highlighting its promising potential for high-power durability.

- (4)

- During fabrication and handling of the LN/SiC membrane prototypes, no structural damage was observed, indicating that bonding with the SiC layer contributes to mechanical reinforcement.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ARIB 2020 and Beyond Ad Hoc Group. Mobile Communications Systems for 2020 and Beyond; White Paper Version 1.0.0; Association of Radio Industries and Businesses (ARIB): Tokyo, Japan, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3GPP. Available online: https://www.3gpp.org (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- White, R.M.; Voltmer, F.W. Direct piezoelectric coupling to surface elastic waves. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1965, 7, 314–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanouchi, K.; Shibayama, K. Elastic surface-wave excitation, using parallel-line electrodes above piezoelectric plates. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1967, 41, 222–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Sasaki, H.; Shimizu, H. A piezoelectric composite resonator consisting of a ZnO film on an anisotropically etched silicon substrate. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1981, 20, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakin, K.M.; Wang, J.S. UHF Composite Bulk Wave Resonators. In Proceedings of the 1980 Ultrasonics Symposium, Boston, MA, USA, 5–7 November 1980; pp. 834–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grudkowski, T.W.; Black, J.F.; Reeder, T.M.; Cullen, D.E.; Wagner, R.A. Fundamental-mode VHF/UHF miniature acoustic resonators and filters on silicon. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1980, 37, 993–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, M.; Nishihara, T.; Tsutsumi, J.; Taniguchi, S.; Yokoyama, T.; Inoue, S. High-Q Resonators Using FBAR/SAW Technology and Their Applications. In Proceedings of the IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Symposium Diges, Long Beach, CA, USA, 17 June 2005; pp. 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aigner, R. SAW and BAW Technologies for RF Filter Applications. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE Ultrasonics Symposium, Beijing, China, 2–5 November 2008; pp. 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Lu, R.; Zhou, H.; Link, S.; Yang, Y.; Li, Z. Surface Acoustic Wave Devices Using Lithium Niobate on Silicon Car-bide. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2020, 68, 3653–3666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, T.; Kishimoto, Y.; Omura, M.; Hashimoto, K. 3.5GHz longitudinal leaky surface acoustic wave resonator using a multilayered waveguide structure for high acoustic energy confinement. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2018, 57, 07LD15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, T.; Omura, M.; Kishimoto, Y.; Kyoya, H.; Mimura, M.; Okunaga, H.; Hashimoto, K. A High Velocity and Wideband SAW on a Thin LiNbO3 Plate Bonded on a Si Substrate in the SHF Range. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS), Glasgow, UK, 6–9 October 2019; Volume 9, pp. 1239–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Fu, S.; Su, R.; Liu, P.; Zhang, S.; Lu, Z.; Xiao, B.; Wang, R.; Song, X.; Zeng, F.; et al. SAW filters on LiNbO3/SiC heterostructure for 5G n77 and n78 band applications. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2023, 70, 1157–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Fu, S.; Xu, H.; Liu, P.; Xu, Q.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, R.; Song, C.; Zeng, F.; et al. High frequency LLSAW filters with higher order modes elimination based on LiNbO3/SiO2/Sapphire substrate. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control Joint Symposium (UFFC-JS), Taipei, Taiwan, 22–26 September 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Zhang, S.; Wu, J.; Zhang, L.; Yao, H.; Fang, X. Near 5-GHz Longitudinal Leaky Surface Acoustic Wave Devices on LiNbO3/SiC Substrates. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2023, 72, 1480–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadota, M.; Kojima, T.; Tanaka, S. 2-8 GHz range high harmonic SAW resonator with grooved electrodes in LiNbO3. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS), Xi’an, China, 11–16 September 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, H.; Suzuki, M.; Kakio, S.; Mizuno, J. Resonance properties of leaky surface acoustic wave harmonics on LiNbO3/quartz bonded structures. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2025, 64, 057005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.; Sekimoto, J.; Fukunaga, K.; Kakio, S.; Yanagitani, T. High overtone mode bulk acoustic wave resonators with polarization inverted ScAlN or SiAlN/AlN films for next-generation high frequency communication systems. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2025, 64, 040803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Barrera, O.; Kramer, J.; Chulukhadze, V.; Hsu, T.-H.; Campbell, J.; Anderson, I.; Lu, R. 23.8-GHz acoustic filter in periodically poled piezoelectric film lithium niobate with 1.52-dB IL and 19.4% FBW. IEEE Microw. Wirel. Tech. Lett. 2024, 34, 391–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, Y.; Tanaka, S.; Kakio, S. Lamb-wave-type high frequency resonator. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2003, 42, 3086–3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadota, M.; Ogami, T.; Yamamoto, K.; Negoro, Y.; Tochishita, H. High-frequency Lamb wave device composed of LiNbO3 thin film. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 48, 07GG08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadota, M.; Ogami, T.; Yamamoto, K.; Tochishita, H.; Negoro, Y. High-frequency Lamb wave device composed of MEMS structure using LiNbO3 thin film and air gap. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2010, 57, 2564–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadota, M.; Ogami, T. 5.4GHz Lamb wave resonator on LiNbO3 thin crystal plate and its application. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 50, 07HD11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadota, M.; Ogami, T.; Kimura, T. Ultrawide-band resonators using shear horizontal-type plate wave and their application. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2013, 52, 07HD04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Gao, A.; Lu, R.; Gong, S. 5 GHZ lithium niobate MEMS resonators with high FoM of 153. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 30th International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 22–26 January 2017; Volume 26, pp. 942–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plessky, V.; Yandrapalli, S.; Turner, P.J.; Villanueva, L.G.; Koskela, J.; Hammond, R.B. 5 GHz laterally-excited bulk-wave resonators (XBARs) based on thin platelets of lithium niobate. Electron. Lett. 2019, 55, 98–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yandrapalli, S.; Plessky, V.; Koskela, J.; Yantchev, V.; Turner, P.; Villanueva, L.G. Analysis of XBAR resonance and higher order spurious modes. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS), Glasgow, UK, 6–9 October 2019; Volume 9, pp. 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Yang, Y.; Link, S.; Gong, S. A1 resonators in 128ºY-cut lithium niobate with electromechanical coupling of 46.4%. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 2020, 29, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Yantchev, V.; Iliev, F.; Plessky, V.; Samadian, S.; Hammond, R.B.; Turner, P.J. Ultra-large-coupling and spurious-free SH0 plate acoustic wave resonators based on thin LiNbO3. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2020, 67, 374–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumenko, N.F. Plate modes in LiTaO3 for application in wide band resonator filters with improved temperature characteristics. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS), Chicago, IL, USA, 3–6 September 2014; pp. 471–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumenko, N.F. Optimal orientations of LiTaO3 for application in plate mode resonators. J. Appl. Phys. 2015, 118, 034505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assila, N.; Kadota, M.; Tanaka, S. High-frequency resonator using A1 Lamb wave mode in LiTaO3 plate. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2019, 66, 1529–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, T.; Daimon, K.; Ogami, T.; Kadota, M. S0 mode Lamb wave resonators using LiNbO3 thin plate on acoustic multilayer reflector. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2013, 52, 07HD03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Shi, B.; Li, Y.; Bailie, W.T.; Wong, Y.; Bao, J.; Hashimoto, K. Use of heavy dielectric materials in solidly mounted A1 mode resonators based on lithium niobate. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2022, 61, SG1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Tang, C.; Deng, C.; Du, F.; He, J.; Hu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Yu, H.; Wang, Z. Lithium niobate MEMS antisymmetric Lamb wave resonators with support structures. Micromachines 2024, 15, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Bao, J.; Hashimoto, K. Use of periodic trenches in SMR-type XBAR for suppression of transverse mode resonances and lateral leakage. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2024, 63, 02SP95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Suzuki, M.; Kakio, S. Analysis of surface acoustic wave resonance properties on piezoelectric substrates with periodic voids. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2023, 62, SJ1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, S.; Suzuki, M.; Kakio, S. Analysis of A0- and A1-mode Lamb waves and SH1-mode plate wave resonance properties on piezoelectric substrate with periodic voids. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2025, 64, 05SP18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Liang, J.; Kawamura, K.; Zhou, H.; Asamura, H.; Uratani, H.; Tiwari, J.; Graham, S.; Ohno, Y.; Nagai, Y.; et al. High thermal conductivity in wafer-scale cubic silicon carbide crystals. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, N.; Kakio, S. Resonance properties of leaky surface acoustic waves and plate waves on LiTaO3 thin plate bonded to SiC-on-Si substrate. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2025, 64, 04SP09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Figures | Structure | LN Angle | hLN/2p 1 | hSiN/2p 1 | hAl/2p 1 | MR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Figure 2 | LN single | 126ºY | 0.10 | – | 4.0% | 050, 0.25 | |

| Figure 3 | LN/SiC | 126ºY | 0.10 | 0.10 | 4.0% | 050, 0.25 | |

| Figure 4 | LN/SiC | 126ºY | 0.08 | 0.02 | 2.0% | 050, 0.25 | |

| Figure 6 and Figure 7 | LN single | 126ºY | 0.04–0.18 | – | 4.0% | 050, 0.25 | |

| 0.04–0.18 | – | 2.0% | 050, 0.25 | ||||

| Figure 8 and Figure 9 | (1) | LN/SiC | 126ºY | 0.03–0.18 | 0.12 | 4.0% | 050, 0.25 |

| (2) | 0.03–0.18 | 0.08 | 2.0% | 050, 0.25 | |||

| (3) | 0.03–0.12 | 0.04 | 2.0% | 050, 0.25 | |||

| (4) | 0.03–0.12 | 0.02 | 2.0% | 050, 0.25 | |||

| Figure 10 and Figure 11 | (5) | LN/SiC | 126ºY | 0.12 | 0.0–0.14 | 2.0% | 050, 0.25 |

| (6) | 0.08 | 0.0–0.16 | 2.0% | 050, 0.25 | |||

| (7) | 0.04 | 0.0–0.12 | 2.0% | 050, 0.25 | |||

| Materials | Items/Process | Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Si substrate | Growth method | MCZ |

| Plane | (111) | |

| Resistivity | >5000 Ωcm | |

| Wafer size | Φ6”, t875 µm | |

| SiC Deposit | Pre-process | Carbonization of Si substrate surface |

| Deposition | 3C-SiC epitaxial growth by CVD | |

| Pressure | Low vacuum (1 × 10−2 Pa) | |

| Temperature | Around 1000 °C | |

| Material gas | Organosilane gas | |

| CMP | Ra < 0.7 nm |

| Sample #A [2p = 8 µm] | Sample #B [2p = 12 µm] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| LiNbO3 (LN) | Cut-angle | 120ºYX (30ºX) | |

| Thickness | 1.43 µm (0.179 1) | 1.48 µm (0.123 1) | |

| SiC | Thickness | 0.9 µm (0.1125 1) | 0.9 µm (0.075 1) |

| Electrode | Film material | Al | |

| Underlying film | Ti | ||

| Al thickness | 400 nm (5% 1) | 400 nm (3.3% 1) | |

| Resonator | Length of 2p | 8.0 µm | 12.0 µm |

| IDT finger | 70.5 pairs | ||

| Aperture width | 25 of 2p | ||

| Metallization ratio | 0.28 | 0.36 | |

| Number of reflectors | 25 (both sides) | ||

| Items | Sample #A [2p = 8.0 µm] | Sample #B [2p = 12.0 µm] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured | Simulated | Measured | Simulated | |

| fr [GHz] | 1.7565 | 1.7370 | 1.1764 | 1.1828 |

| fa [GHz] | 1.9007 | 1.8324 | 1.3207 | 1.2626 |

| FBW (%) | 7.59 | 5.21 | 10.92 | 6.32 |

| Keff2 (%) | 17.39 | 12.20 | 24.24 | 14.56 |

| Qfr | 68.3 | 222.7 | 39.7 | 219.0 |

| Qfa | 174.1 | 241.1 | 89.1 | 242.8 |

| AR (dB) | 46.3 | 54.8 | 44.9 | 58.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Watanabe, N.; Kakio, S.; Sakaida, Y.; Oku, H.; Hishiki, S. High-Performance and Thermally Robust A1-Mode Lamb Wave Resonators on Bonded LiNbO3/SiC Membranes. Micromachines 2025, 16, 1413. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121413

Watanabe N, Kakio S, Sakaida Y, Oku H, Hishiki S. High-Performance and Thermally Robust A1-Mode Lamb Wave Resonators on Bonded LiNbO3/SiC Membranes. Micromachines. 2025; 16(12):1413. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121413

Chicago/Turabian StyleWatanabe, Noriyuki, Shoji Kakio, Yoshiki Sakaida, Hidehiko Oku, and Shigeomi Hishiki. 2025. "High-Performance and Thermally Robust A1-Mode Lamb Wave Resonators on Bonded LiNbO3/SiC Membranes" Micromachines 16, no. 12: 1413. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121413

APA StyleWatanabe, N., Kakio, S., Sakaida, Y., Oku, H., & Hishiki, S. (2025). High-Performance and Thermally Robust A1-Mode Lamb Wave Resonators on Bonded LiNbO3/SiC Membranes. Micromachines, 16(12), 1413. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121413