Numerical Investigation of Non-Newtonian Fluid Rheology in a T-Shaped Microfluidics Channel Integrated with Complex Micropillar Structures Under Acoustic, Electric, and Magnetic Fields

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Methodology

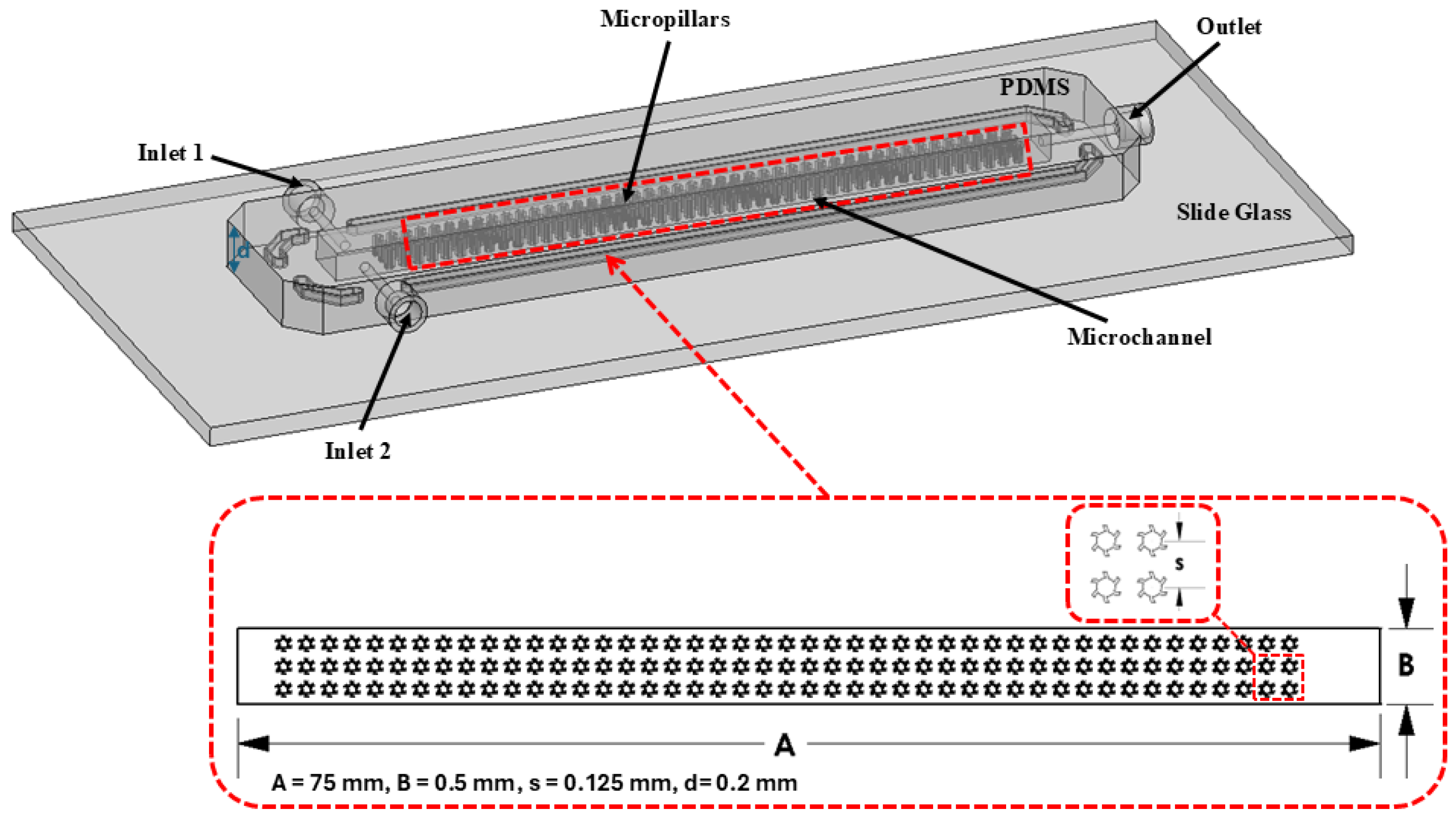

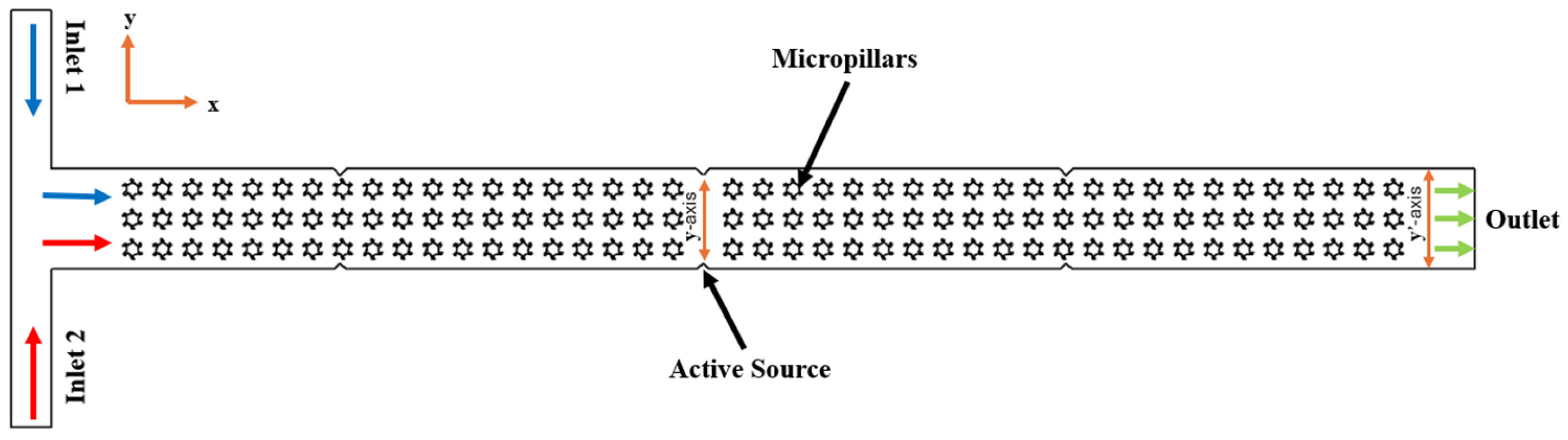

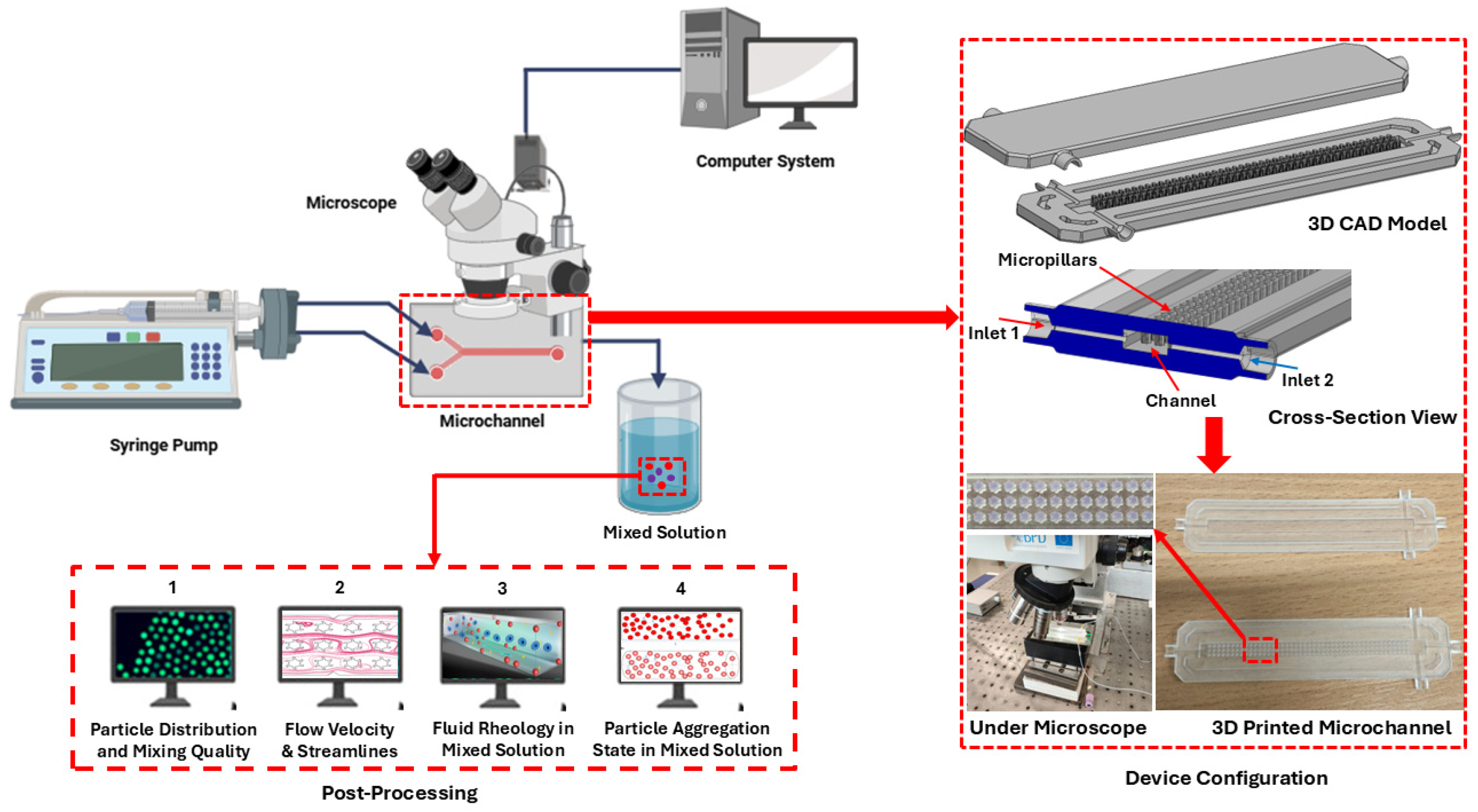

2.1. Device Configurations

2.2. Material

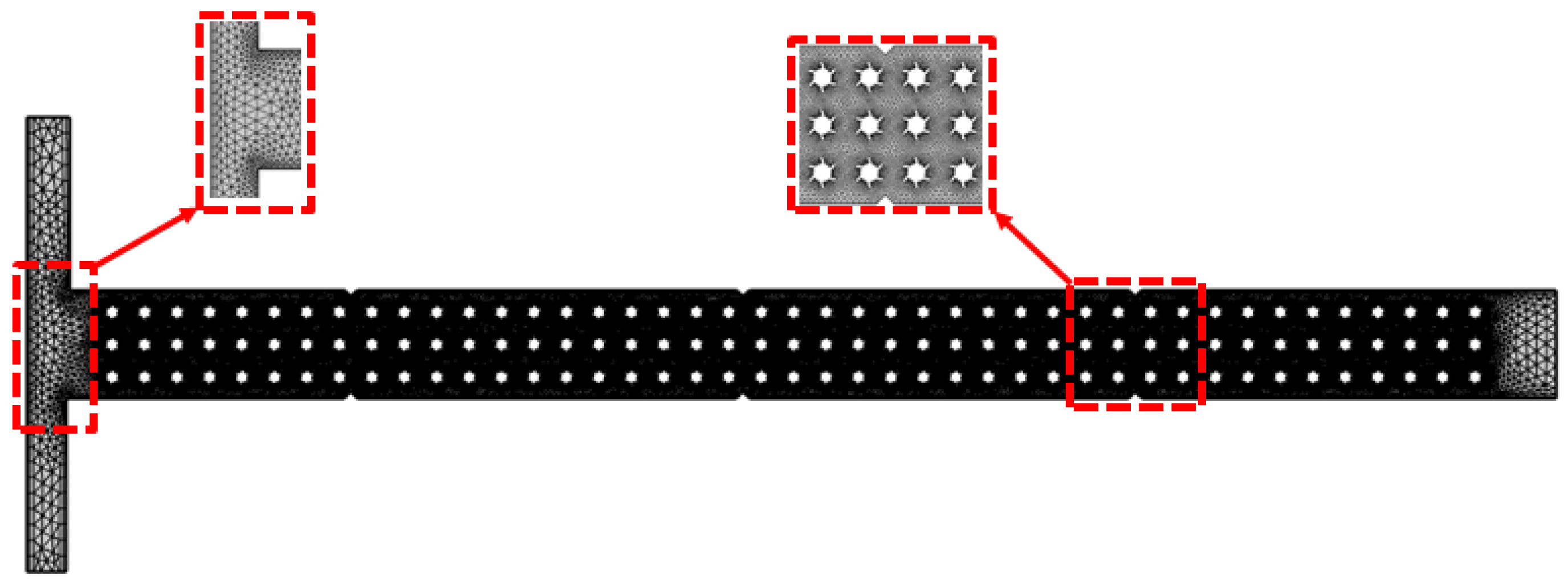

2.3. Fluid Domain and Meshing

2.4. Mathematical Formulation

2.4.1. Laminar Flow

2.4.2. Pressure Acoustics

2.4.3. Electric Current

2.4.4. Magnetic Field

2.5. Numerical Settings and Boundary Conditions

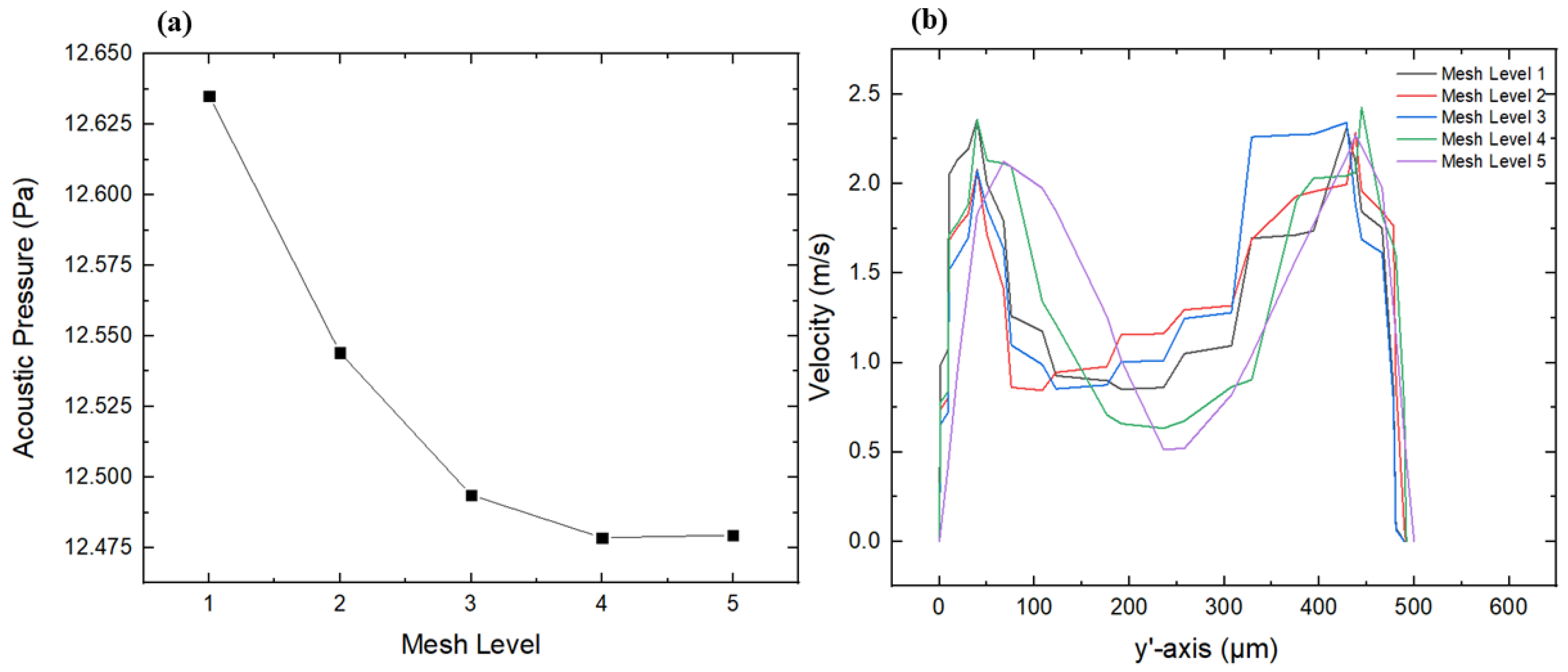

2.6. Mesh Sensitivity Analysis

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Flow Field

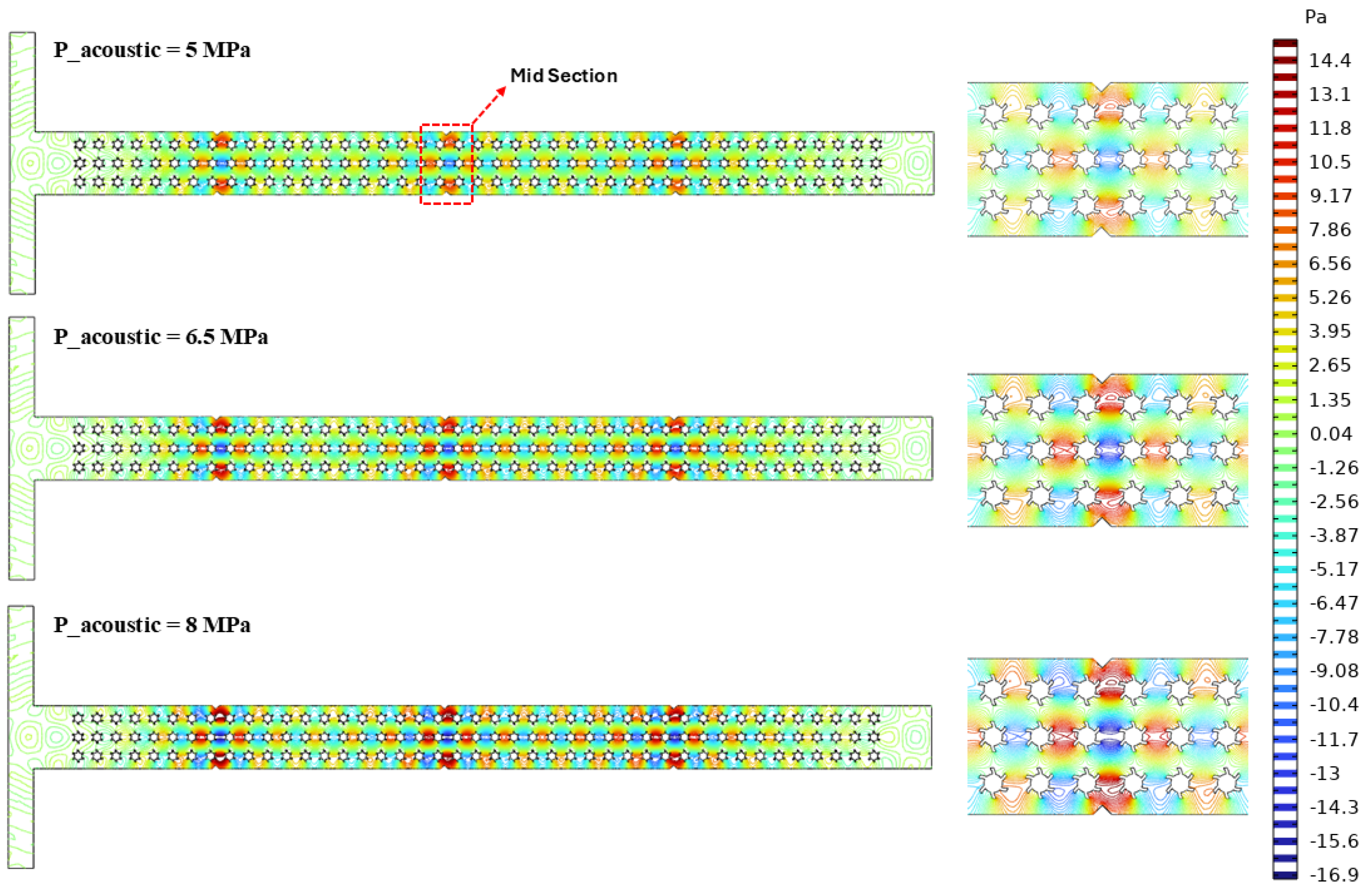

3.2. Acoustic Field

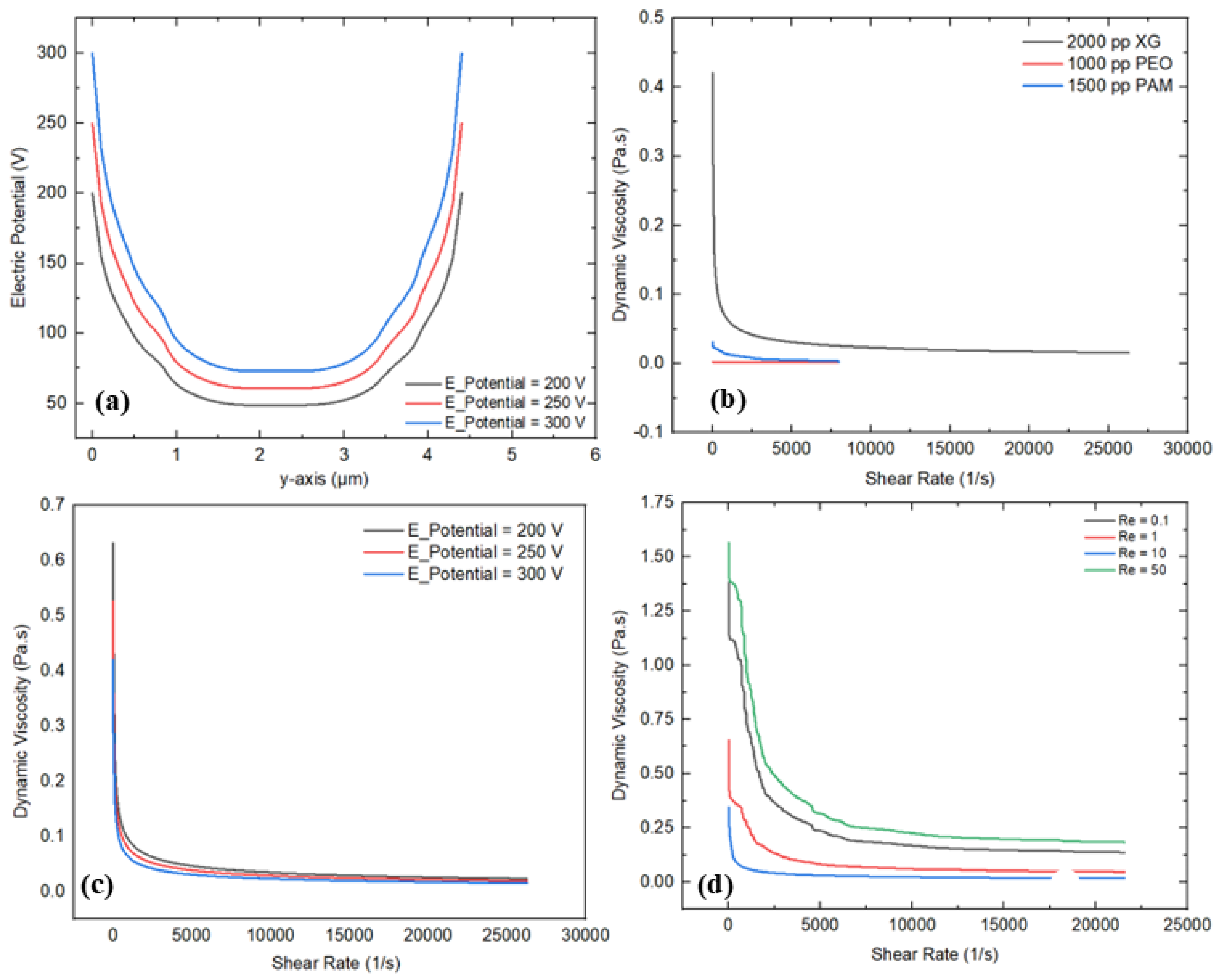

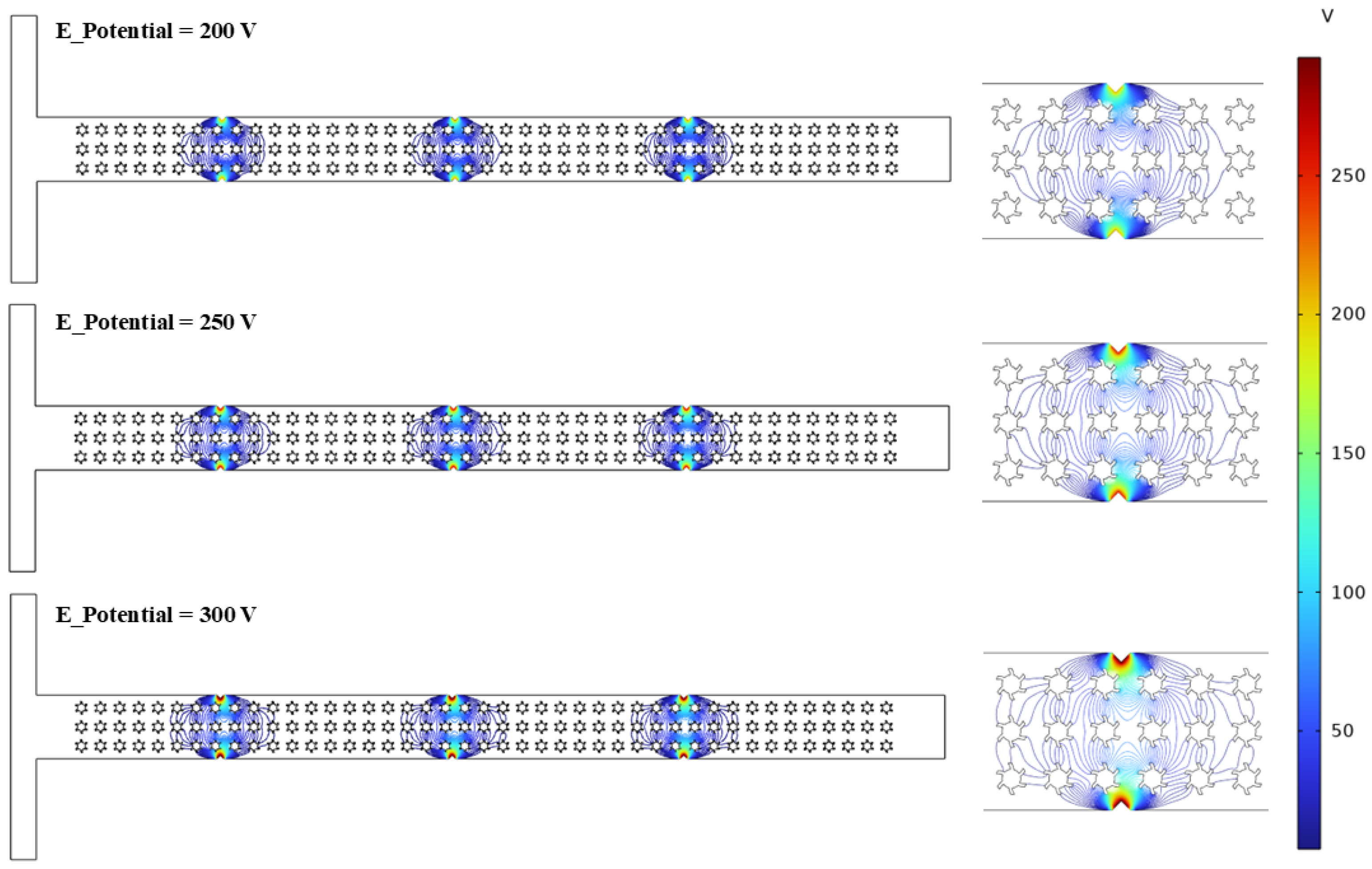

3.3. Electric Field

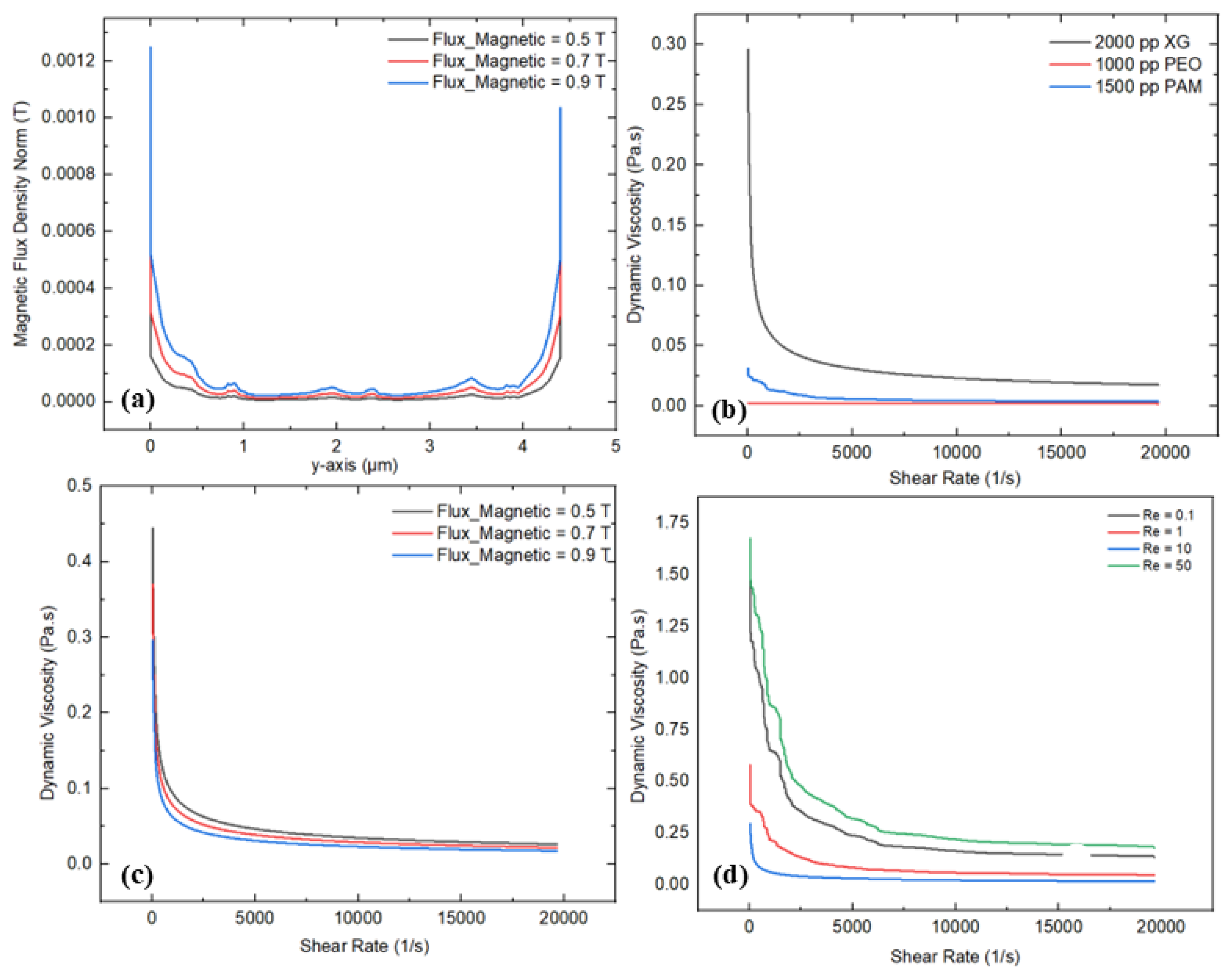

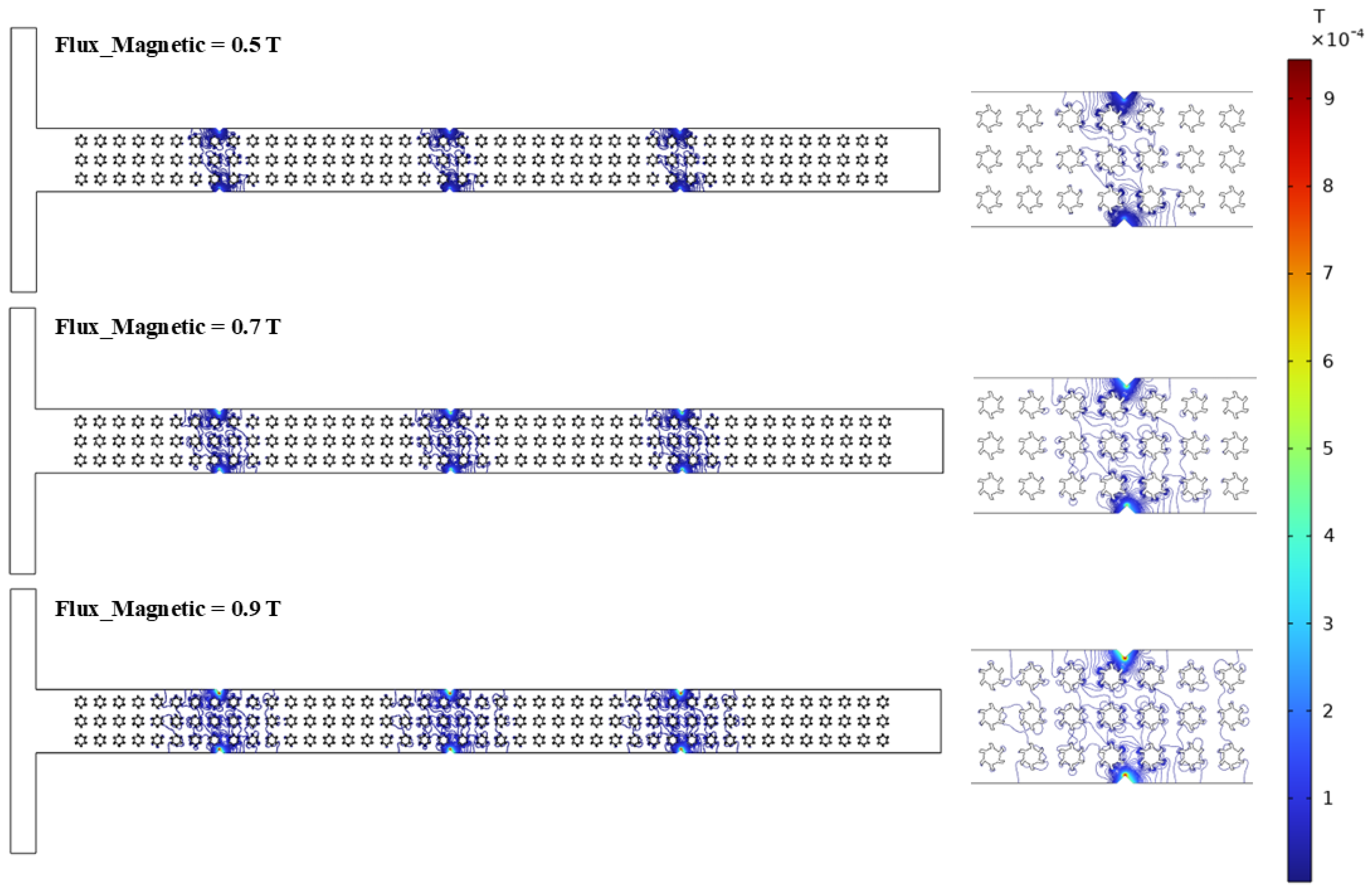

3.4. Magnetic Field

4. Experimental Framework

5. Conclusions

- The integration of external active fields (acoustic, electric, and magnetic) and the incorporation of complex micropillar structures significantly influences the rheological behavior and fluid dynamics of non-Newtonian fluids while flowing through the microchannel. The combination of these factors can significantly help to modify fluid behavior and rheological characteristics and provide better shear control in a microfluidics channels.

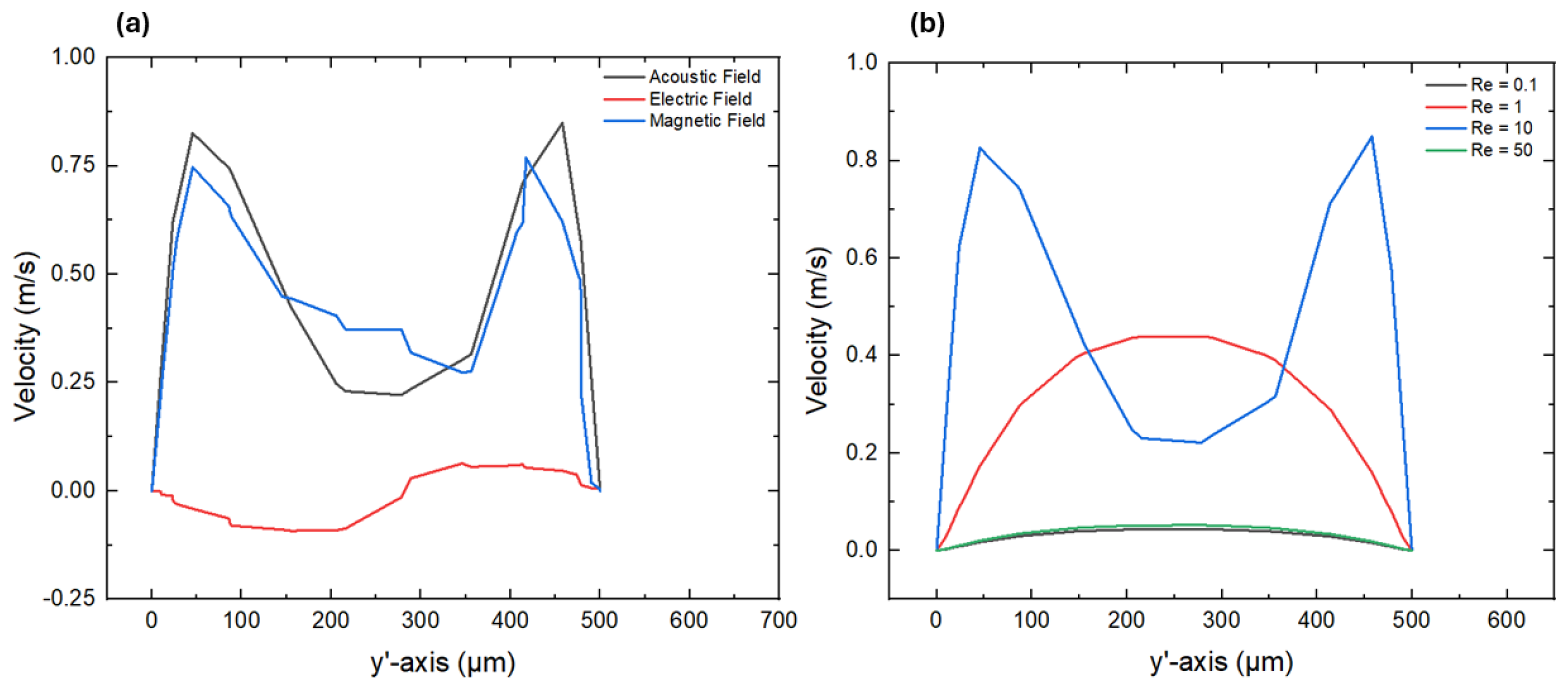

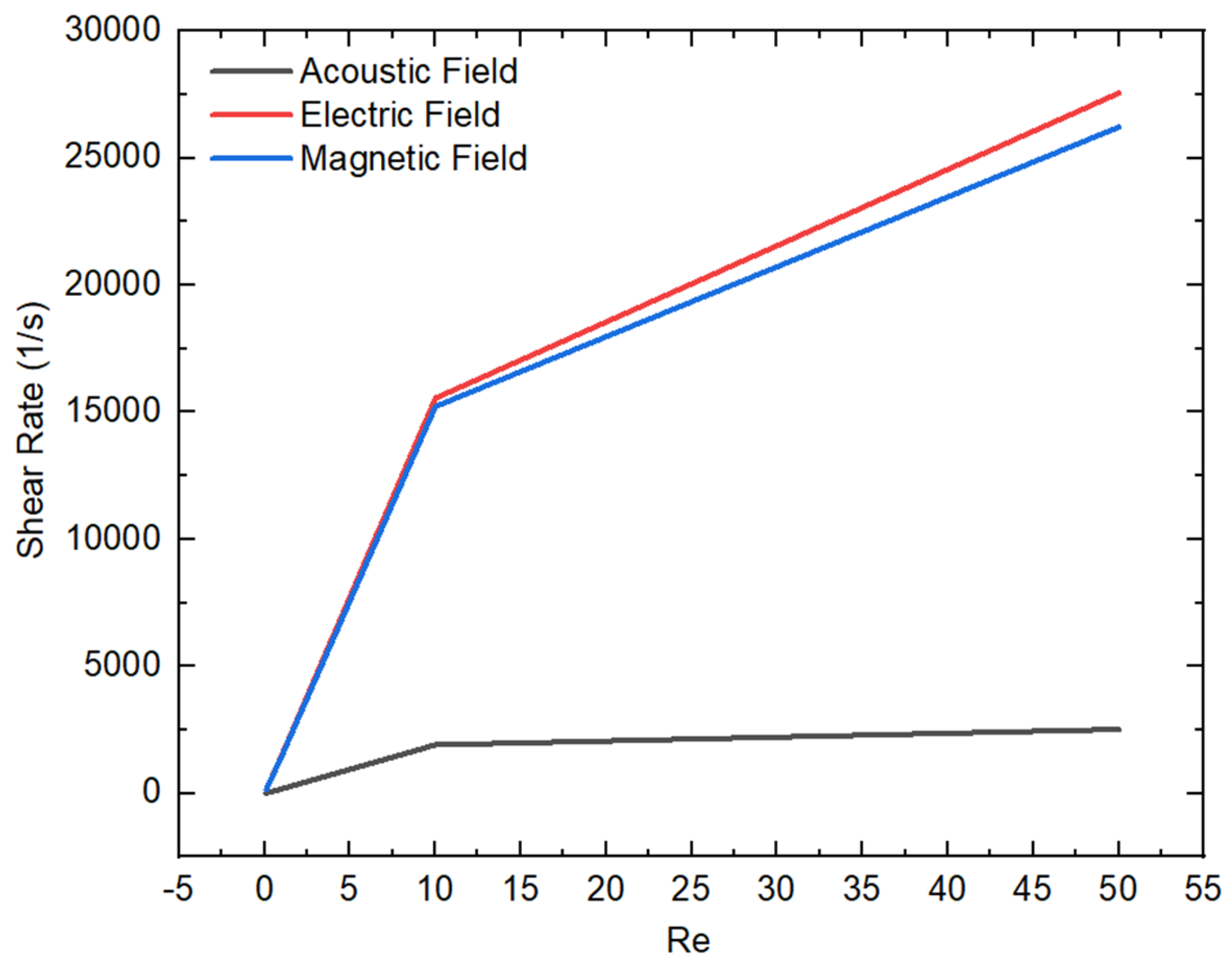

- The flow field demonstrates that the external active fields and complex micropillar structures significantly influence the flow behavior and velocity profiles of non-Newtonian fluids within the microfluidics channel. The maximum velocity magnitude of 0.84 m/s is observed under an acoustic field, followed by a magnetic field, with 0.76 m/s, and an electric field, with 0.06 m/s. These findings reveal the substantial role of active fields and Re in the design and modification of microfluidics channels.

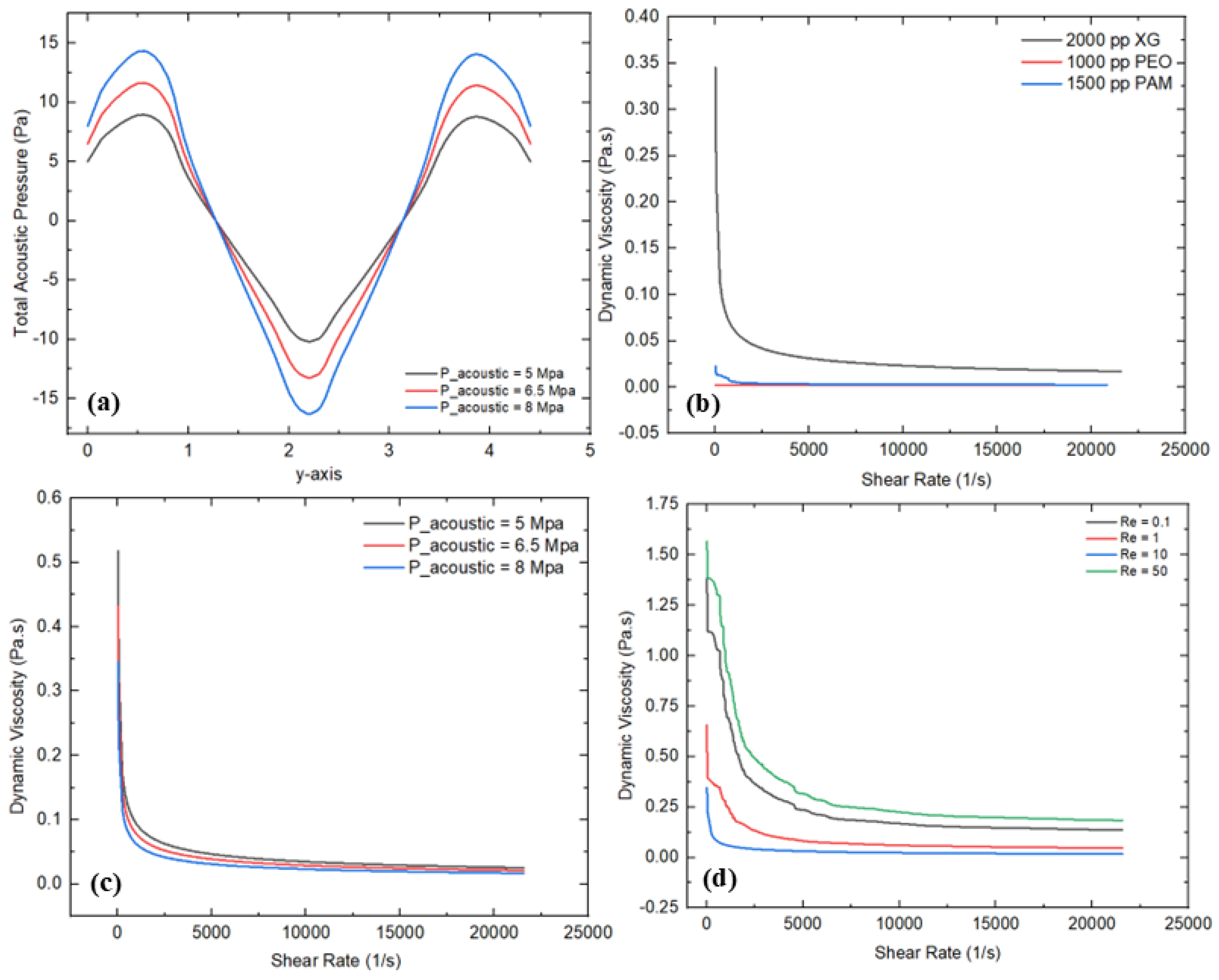

- The acoustic field reveals that the acoustic pressure and complex micropillar structures significantly influence the fluid rheology. As the acoustic pressure rises from 5 Mpa to 8 Mpa, the total acoustic pressure increases by 1.6 times the minimum values at 5 Mpa. This may cause a reduction in dynamic viscosity from 0.51 Pa·s at 8 Mpa to 0.34 Pa·s at 5 Mpa. In addition, the rheological behavior is also influenced by different polymer solutions, as XG exhibiting 17 times reduction in viscosity compared to the other polymer solutions. The findings demonstrate that an acoustic field can be beneficial to stabilize laminar flow conditions and improve the rheological behavior where uniform flow is needed.

- The electric field induces a higher shear rate compared to the other external active fields, resulting in more chaotic flow patterns within the microchannel and an evident reduction in dynamic viscosity, indicating convincing shear-thinning behavior. As the applied voltage increases from 200 V to 300 V, the dynamic viscosity reduces from 0.63 Pa·s to 0.42 Pa·s. In addition, XG also demonstrates substantial shear-thinning behavior, with a dynamic viscosity of 0.42 Pa·s, which is nearly 10 and 15 times higher than PAM and PEO, respectively. Moreover, higher voltages produce strong electric field intensities and micro-vortex formation, resulting in significant variation in velocity profiles at the outlet section (y’-axis) compared to the other external active fields. This electric field behavior can be leveraged to design and optimize microfluidics devices by modifying rheological properties and controlling shear rates.

- Similarly, the magnetic field also generates moderate shear rate changes and made secondary flow patterns within the microchannel, indicating a clear shear-thinning behavior. The maximum magnetic flux densities recorded are 0.0012 T at 0.9 T and 0.00038 T at 0.5, with a subsequent reduction in dynamic viscosity from 0.44 Pa·s at 0.5 T to 0.29 Pa·s at 0.9 T. In addition, XG demonstrates significant shear-thinning behavior; as the shear rate increases, the dynamic viscosity decreases from 0.29 Pa·s to 0.0023 Pa·s. These findings can be beneficial to control the flow characteristics and for shear control for specified applications such as enhancing mixing with complex fluids.

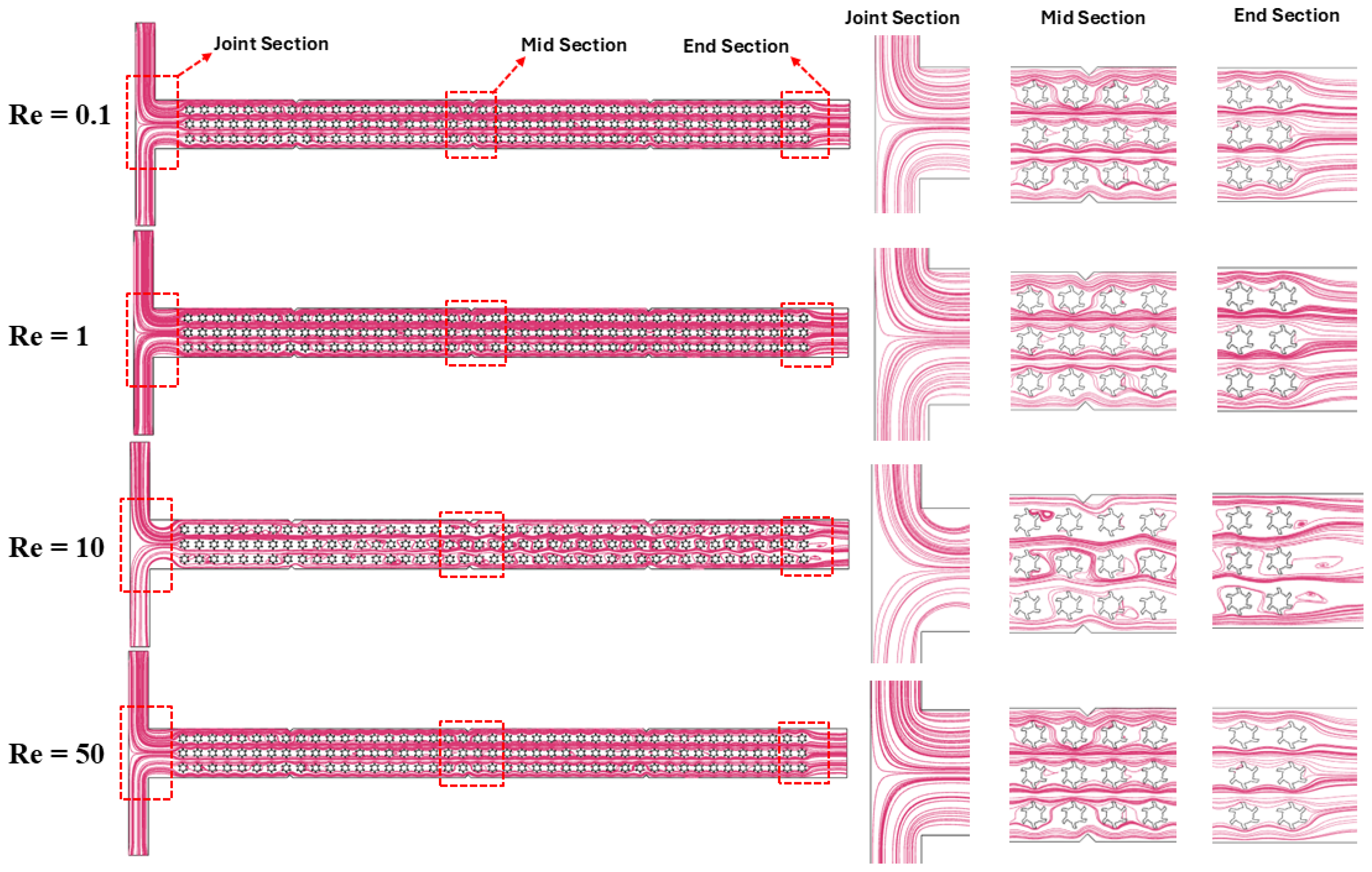

- Moreover, the influence of varying the Reynold number on the fluid rheology was also studied. As Re increases from 0.1 to 50, the flow transitions from laminar to more chaotic, resulting in a higher shear rate. In addition, more chaotic flow is observed under electric and magnetic fields, while less chaotic flow is examined in case of an acoustic field, which maintains a more uniform flow within the microchannel.

- Based on the current findings, an experimental framework is proposed to study non-Newtonian fluid mixing in a T-shaped microfluidics channel under external active fields. An experimental framework comprises a syringe pump, optical microscope, microchannel, and computer system. The microchannel device is fabricated using a high-resolution SLA printer with clear photopolymer resin material. The post-processing will include examining the particle distribution, mixing quality, fluid rheology, and particle aggregation. Overall, the proposed setup offers a vigorous framework for validating numerical models and studying complex non-Newtonian fluids under different external active fields.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Faradonbeh, V.R.; Rabiei, S.; Rabiei, H.; Goodarzi, M.; Safaei, M.R.; Lin, C.X. Power-law fluid micromixing enhancement using surface acoustic waves. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 347, 117978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, B. Thermofluidic characteristics of electrokinetic flow in a rotating microchannel in presence of ion slip and Hall currents. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2021, 126, 105350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, M.; Palevicius, A.; Jurenas, V.; Pilkauskas, K.; Janusas, G. Design and Investigation of a Passive-Type Microfluidics Micromixer Integrated with an Archimedes Screw for Enhanced Mixing Performance. Micromachines 2025, 16, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, S.; Jin, Y.; Lin, Y.; He, Y.; Zhang, P.; Ge, Z.; Yang, W. Micromixing within microfluidic devices: Fundamentals, design, and fabrication. Biomicrofluidics 2023, 17, 061503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, A.K.; Kumar, M.; Dayal, R.; Suman, S. Effects of geometry and electric field on non-Newtonian fluid mixing in induced charge electrokinetic micromixers. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 159, 108191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, T.; Lin, X.; Yuan, S.; Zhou, M.; Jiang, B.; Jia, Y. Mixing enhancement in a straight microchannel with ultrasonically activated attached bubbles. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 217, 124635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Wang, B.; Cai, Y.; Song, Q. An overview on state-of-art of micromixer designs, characteristics and applications. Anal. Chim. Acta 2023, 1279, 341685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raihan, M.K.; Jagdale, P.P.; Wu, S.; Shao, X.; Bostwick, J.B.; Pan, X.; Xuan, X. Flow of Non-Newtonian Fluids in a Single-Cavity Microchannel. Micromachines 2021, 12, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagdale, P.P.; Li, D.; Shao, X.; Bostwick, J.B.; Xuan, X. Fluid rheological effects on the flow of polymer solutions in a contraction–expansion microchannel. Micromachines 2020, 11, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, C.-S.; Baldeck, P.L.; Nie, Y.-M.; Lee, Y.-H.; Lin, Z.-D.; Chiang, C.-C.; Lin, C.-L. Design and evaluation of a 3D multi-manifold micromixer realized by a double-Archimedes-screw for rapid mixing within a short distance. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2021, 120, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juraeva, M.; Kang, D.J. Mixing Performance of a cross-channel split-and-recombine micro-mixer combined with mixing cell. Micromachines 2020, 11, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Cheng, X. Numerical investigation of electroosmotic mixing in a contraction–expansion microchannel. Chem. Eng. Process.—Process Intensif. 2023, 192, 109492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endaylalu, S.A.; Tien, W.-H. A Numerical Investigation of the Mixing Performance in a Y-Junction Microchannel Induced by Acoustic Streaming. Micromachines 2022, 13, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, M.; Janusas, G.; Naginevičius, V.; Palevicius, A. The Design and Investigation of Hybrid a Microfluidic Micromixer. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.-Y.; Sivan, V.; Petersen, P.; Zhang, W.; Morrison, P.D.; Kalantar-zadeh, K.; Mitchell, A.; Khoshmanesh, K. Liquid Metal Actuator for Inducing Chaotic Advection. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2014, 24, 5851–5858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, D.; Zabihi-Hesari, A.; Passandideh-Fard, M. Rapid mixing in micromixers using magnetic field. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2017, 255, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Sun, C.P.; Fields, M.; Li, Y.; Haake, D.A.; Churchill, B.M.; Ho, C.M. An unsteady microfluidic T-form mixer perturbed by hydrodynamic pressure. J. Micromechanics Microengineering 2008, 18, 045015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Tsou, C. The implementation of a thermal bubble actuated microfluidic chip with microvalve, micropump and micromixer. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2014, 210, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayareh, M.; Ashani, M.N.; Usefian, A. Active and passive micromixers: A comprehensive review. Chem. Eng. Process.—Process Intensif. 2020, 147, 107771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, P.K.; Narayanan, S. Acoustic effects on micro-channel flow of Newtonian and non-Newtonian fluids. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 052006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsalam, S.I.; Vafai, K. Combined effects of magnetic field and rheological properties on the peristaltic flow of a compressible fluid in a microfluidic channel. Eur. J. Mech. B/Fluids 2017, 65, 398–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharib, G.; Bütün, I.; Muganlı, Z.; Kozalak, G.; Namlı, İ.; Sarraf, S.S.; Ahmadi, V.E.; Toyran, E.; van Wijnen, A.J.; Koşar, A. Biomedical Applications of Microfluidic Devices: A Review. Biosensors 2022, 12, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, H.; Chen, X.; Zeng, X. Optimization of micromixer with Cantor fractal baffle based on simulated annealing algorithm. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2021, 148, 111048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouadri, A.; Douroum, E.; Lasbet, Y.; Naas, T.T.; Khelladi, S.; Makhlouf, M. Comparative study of mixing behaviors using non-Newtonian fluid flows in passive micromixers. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2021, 201, 106472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Zhou, M.; Peng, T.; Li, Q.; Jiang, F. An investigation of chaotic mixing behavior in a planar microfluidic mixer. Phys. Fluids 2022, 34, 032007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaikwad, H.S.; Mondal, P.K. Rheology modulated high electrochemomechanical energy conversion in soft narrow-fluidic channel. J. Non-Newton. Fluid Mech. 2020, 285, 104381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, F.; Tao, W. Experimental investigation of non-Newtonian liquid flow in microchannels. J. Non-Newton. Fluid Mech. 2012, 173–174, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Zhan, X.; Yu, L.; Ye, B. Acoustic vibration-induced stress dynamics in high viscosity non-Newtonian fluids within a wedge flow channel. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2025, 23, 100807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Zeng, Y.; Li, M.; Liang, C. Electroosmotic flow of non-newtonian fluid in porous polymer membrane at high zeta potentials. Micromachines 2020, 11, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khashan, S.; Odhah, A.A.; Taha, M.; Alazzam, A.; Al-Fandi, M. Enhanced microfluidic multi-target separation by positive and negative magnetophoresis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslam, H.M.; Hataminia, F.; Asadi-Saghandi, H.; Fayazbakhsh, F.; Tabatabaei, N.; Ghanbari, H. Characterization and numerical simulation of a new microfluidic device for studying cells-nanofibers interactions based on collagen/PET/PDMS composite. Front. Lab Chip Technol. 2024, 3, 1411171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.L.; Raihan, M.K.; Tabarhoseini, S.M.; Gabbard, C.T.; Islam, M.; Lee, Y.-H.; Bostwick, J.B.; Fu, L.-M.; Xuan, X. Electrokinetic flow instabilities in shear thinning fluids with conductivity gradients. Soft Matter 2024, 21, 699–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Cai, C.; Sun, H.; Jia, N.; Liu, J.; Xie, Z. Flexible concentration control of Newtonian and non-Newtonian fluids in a microfluidic device via AC electrothermal flow. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2024, 380, 116043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magesh, A.; Tamizharasi, P.; Vijayaragavan, R. Non-Newtonian fluid flow with the influence of induced magnetic field through a curved channel under peristalsis. Heat Transf. 2023, 52, 4946–4961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Raihan, M.K.; Yu, L.; Wu, S.; Kim, N.; Till, S.R.; Song, Y.; Xuan, X. An experimental study of the merging flow of polymer solutions in a T-shaped microchannel. Soft Matter 2023, 19, 3207–3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llamas, C.G.; Durubal, M.P.; Huijgen, A.; Buist, K.; Kuipers, H.; Baltussen, M. Numerical investigation of Non-Newtonian droplet-droplet collisions using VOF and LFRM. In Proceedings of the ILASS Europe 2023, 32nd Conference on Liquid Atomization & Spray Systems, Napoli, Italy, 4–7 September 2023; pp. 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Poole, R.J.; Escudier, M.P.; Afonso, A.; Pinho, F.T. Laminar flow of a viscoelastic shear-thinning liquid over a backward-facing step preceded by a gradual contraction. Phys. Fluids 2007, 19, 093101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, C.; Campos-Silva, I.; Méndez, F.; Arcos, J.; Bautista, O. Acoustic streaming in Maxwell fluids generated by standing waves in two-dimensional microchannels. J. Fluid Mech. 2022, 933, A59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Brunet, P.; Liu, S.; Guo, X.; Royon, L.; Qin, X.; Wei, X. Acoustofluidics at Audible Frequencies—A Review. Engineering 2024, 44, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barman, C.; Bandopadhyay, A. Mixing intensification in Carreau–Yasuda fluid promoted by magnetohydrodynamic flow manipulation—A numerical study. Flow 2025, 5, E11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, L.; Cui, D.; Shen, J.; Dutta, D.; Brown, W.; Zhang, L.; Dabipi, I.K. Electroosmotic Mixing of Non-Newtonian Fluid in a Microchannel with Obstacles and Zeta Potential Heterogeneity. Micromachines 2021, 12, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Qian, S.; Liu, Z. Electroosmotic Flow of Viscoelastic Fluid through a Constriction Microchannel. Micromachines 2021, 12, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, S.; Rashid, A.I.; Waghmare, P.R.; Nobes, D.S. Measurement of the flow behavior index of Newtonian and shear-thinning fluids via analysis of the flow velocity characteristics in a mini-channel. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, B.; Shankar, V.; Das, D. Onset of transition in the flow of polymer solutions through deformable tubes. Phys. Fluids 2019, 31, 114103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yonemoto, Y.; Yamahata, Y.; Kawahara, A. Rheological Property Changes in Polyacrylamide Aqueous Solution Flowed Through Microchannel Under Low Reynolds Number and High Shear Rate Conditions. Micromachines 2025, 16, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedayati, N.; Ramiar, A.; Sedighi, K. Investigation of Visco-rheological Properties of Polymeric Fluid on Electrothermal Pumping. J. Appl. Comput. Mech. 2024, 10, 164–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kausar, A. Electrorheological Fluids with Polymers/Polymeric Nanocomposites—Retrospective and Prospective. Polym. Technol. Mater. 2025, 64, 1475–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrepally, S.; Jouenne, S.; Olmsted, P.D.; Lequeux, F. Scission of flexible polymers in contraction flow: Predicting the effects of multiple passages. J. Rheol. 2020, 64, 601–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Polymer | (mPa·s) | (mPa·s) | n | (ms) | EI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 ppm xanthan gum (XG) | 1740 | 1.8 | 0.33 | ≈0 | ≈0 |

| 1000 ppm polyethylene oxide (PEO) | 2.4 | 1.5 | 0.85 | 1.5 | 0.37 |

| 1500 ppm polyacrylamide (PAM) | 1200 | 1.6 | 0.5 | 800 | 0.45 |

| Mesh Refinement Level | Number of Elements | Number of Nodes | Maximum Acoustic Pressure (Pa) | Relative Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 50,193 | 31,678 | 12.6350 | 1.246 |

| 2 | 50,198 | 31,781 | 12.5440 | 0.517 |

| 3 | 79,300 | 49,981 | 12.4936 | 0.113 |

| 4 | 83,666 | 52,256 | 12.4785 | 0.008 |

| 5 | 130,283 | 76,157 | 12.4795 | -- |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Waqas, M.; Palevicius, A.; Senol, C.O.; Janusas, G. Numerical Investigation of Non-Newtonian Fluid Rheology in a T-Shaped Microfluidics Channel Integrated with Complex Micropillar Structures Under Acoustic, Electric, and Magnetic Fields. Micromachines 2025, 16, 1390. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121390

Waqas M, Palevicius A, Senol CO, Janusas G. Numerical Investigation of Non-Newtonian Fluid Rheology in a T-Shaped Microfluidics Channel Integrated with Complex Micropillar Structures Under Acoustic, Electric, and Magnetic Fields. Micromachines. 2025; 16(12):1390. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121390

Chicago/Turabian StyleWaqas, Muhammad, Arvydas Palevicius, Cengizhan Omer Senol, and Giedrius Janusas. 2025. "Numerical Investigation of Non-Newtonian Fluid Rheology in a T-Shaped Microfluidics Channel Integrated with Complex Micropillar Structures Under Acoustic, Electric, and Magnetic Fields" Micromachines 16, no. 12: 1390. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121390

APA StyleWaqas, M., Palevicius, A., Senol, C. O., & Janusas, G. (2025). Numerical Investigation of Non-Newtonian Fluid Rheology in a T-Shaped Microfluidics Channel Integrated with Complex Micropillar Structures Under Acoustic, Electric, and Magnetic Fields. Micromachines, 16(12), 1390. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121390