High-Precision Optical Angle Detection Method for Two-Dimensional MEMS Mirrors

Abstract

1. Introduction

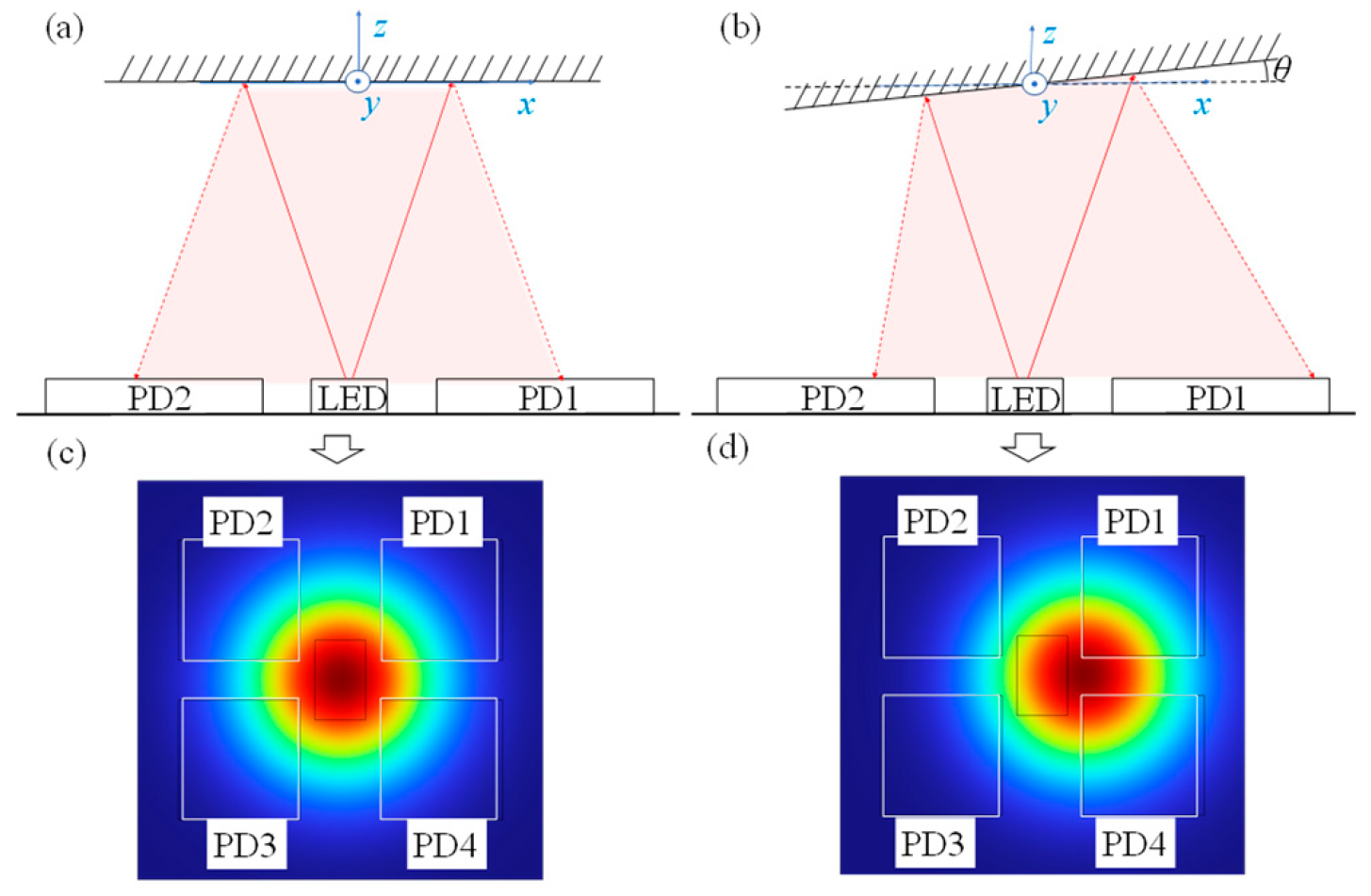

2. Design of Optical Detection

3. Detected Angle Calculation

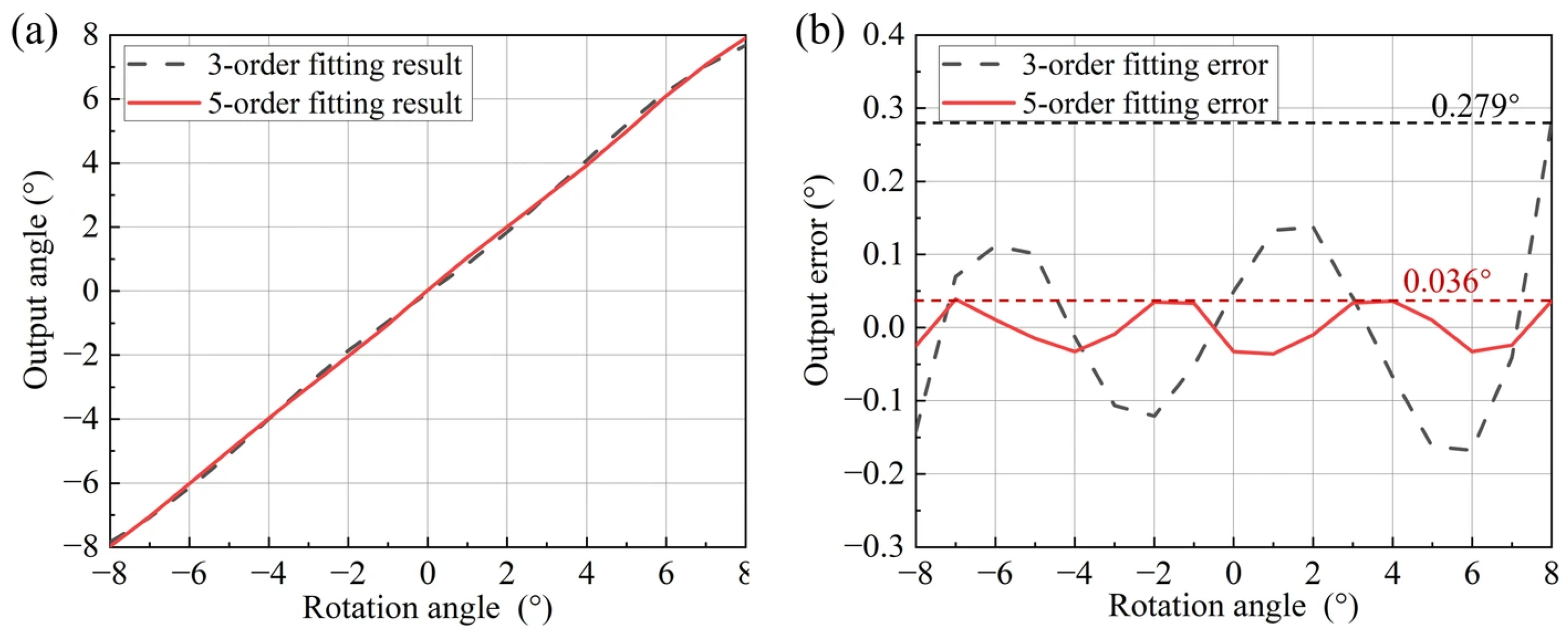

4. Simulation Analysis

5. Hardware Design

6. Experimental Verification

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abe, Y.; Akanuma, G.; Shinkawa, M.; Hashiguchi, T.; Sato, M.; Suzuki, S.; Sakai, A.; Ishimoto, Y. Piezoelectric MEMS Mirror with Cantilever-Type Actuator for Compact, Low-Voltage Drive, and Wide-Angle Deflection. In Proceedings of the IEEE 37th International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS), Austin, TX, USA, 21–25 January 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Solgaard, O.; Godil, A.A.; Howe, R.T.; Lee, L.P.; Peter, Y.-A.; Zappe, H. Optical MEMS: From micromirrors to complex systems. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 2014, 23, 517–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.Y.; Tseng, S.H.; Lu, M.S.C. Design and Characterization of a CMOS Electromagnetic Scanning Mirror for LiDAR Applications. IEEE Sens. Lett. 2022, 6, 5000504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.-Y.; Wysocki, L.; Yarar, E.; Wille, G.; Röhr, F.; Albers, J.; Gu-Stoppel, S. Low Power Compact 3D-Constructed AlScN Piezoelectric MEMS Mirrors for Various Scanning Strategies. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilchrist, K.H.; Dausch, D.E.; Grego, S. Electromechanical performance of piezoelectric scanning mirrors for medical endoscopy. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2012, 178, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozaki, T.; Ohta, N.; Fujiyoshi, M. Highly Linear and Wide Non-Resonant Two-Degree-of-Freedom Piezoelectric Laser Scanner. Sensors 2022, 22, 4215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Gong, M.; You, Z. A motion characteristics modeled angular position sensor by nonlinear transfer of differential capacitance for miniaturized scanning mirrors. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2023, 9, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y.; Xiong, J.; Dong, R.; Tan, Q. Scanning Angle Control of MEMS Micro-mirror Used in LIDAR. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Real-Time Computing and Robotics (RCAR), Guiyang, China, 17–22 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ran, L.; Ma, Z.; Li, T.; He, J.; Wu, J.; Zhou, W. Optical Sensor for Scanning Angle of Micromirror with Improved 2D Calibration Method. Micromachines 2025, 16, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grahmann, J.; Dreyhaupt, A.; Drabe, C.; Schrödter, R.; Kamenz, J.; Sandner, T. MEMS-mirror based trajectory resolution and precision enabled by two different piezoresistive sensor technologies. In Proceedings of the MOEMS and Miniaturized Systems XV, San Francisco, CA, USA, 15–17 February 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, A.C.-L.; Lai, H.Y.-H.; Lin, T.-W.; Fu, S.-G.; Lu, M.S.-C. An electrostatically driven 2D micro-scanning mirror with capacitive sensing for projection display. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2015, 222, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanović, V.; Siu, N.; Kasturi, A.; Radojičić, M.; Su, Y. MEMSEye for optical 3D position and orientation measurement. In Proceedings of the MOEMS and Miniaturized Systems X, San Francisco, CA, USA, 14 February 2011; Volume 7930. [Google Scholar]

- Ataman, Ç.; Lani, S.; Noell, W.; de Rooij, N.F. A dual-axis pointing mirror with moving magnet actuation. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2013, 23, 025002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, I.; Sawada, R.; Higurashi, E.; Sanada, S.; Chino, D. Integrated micro-displacement sensor that measures tilting angle and linear movement of an external mirror. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2007, 138, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inokuchi, M.; Ando, H.; Kinostia, M.; Akase, K.; Higurashi, E.; Sawada, R. Development of a micro displacement sensor with monolithic-integrated two-dimensionally distributed photodiodes. In Proceedings of the IEEE/LEOS International Conference on Optical MEMS and Nanophotonics, Clearwater, FL, USA, 17–20 August 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X.; Sun, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, L.; Xie, H. Integrated Optoelectronic Position Sensor for Scanning Micromirrors. Sensors 2018, 18, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, H.; Zhou, W.; Ran, L.; Yu, H.; Peng, B.; Hao, R. A high-resolution optical displacement detection method for piezoelectric micro vibratory stage. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 67, 10897–10904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeg, K.-J.; Binda, M.; Natali, D.; Caironi, M.; Noh, Y.-Y. Organic light detectors: Photodiodes and phototransistors. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 4267–4295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Performance Metric | Piezoresistive Scheme | Proposed Optical Scheme |

|---|---|---|

| Biaxial Coupling | ~1.5%/° | <1.37%/° |

| Measurement Range | ±7.5° | ±8° |

| Measurement Error | >0.08° @ ±7.5° | 0.03°~0.036° @ ±8° |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ran, L.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Li, T.; He, J.; Wu, J.; Zhou, W. High-Precision Optical Angle Detection Method for Two-Dimensional MEMS Mirrors. Micromachines 2025, 16, 1346. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121346

Ran L, Wang Y, Ma Z, Li T, He J, Wu J, Zhou W. High-Precision Optical Angle Detection Method for Two-Dimensional MEMS Mirrors. Micromachines. 2025; 16(12):1346. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121346

Chicago/Turabian StyleRan, Longqi, Yan Wang, Zhongrui Ma, Ting Li, Jiangbo He, Jiahao Wu, and Wu Zhou. 2025. "High-Precision Optical Angle Detection Method for Two-Dimensional MEMS Mirrors" Micromachines 16, no. 12: 1346. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121346

APA StyleRan, L., Wang, Y., Ma, Z., Li, T., He, J., Wu, J., & Zhou, W. (2025). High-Precision Optical Angle Detection Method for Two-Dimensional MEMS Mirrors. Micromachines, 16(12), 1346. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121346