Abstract

Paralytic shellfish toxins (PSTs) are an increasingly important source of pollution. Bivalves, as the main transmission medium, accumulate and metabolize PSTs while protecting themselves from damage. At present, the resistance mechanism of bivalves to PSTs is unclear. In this study, Mytilus galloprovincialis and Argopecten irradians were used as experimental shellfish species for in situ monitoring. We compared the inflammatory-related gene responses of the two shellfish during PSTs exposure by using transcriptomes. The results showed that the accumulation and metabolism rate of PSTs in M. galloprovincialis was five-fold higher than that in A. irradians. The inflammatory balance mechanism of M. galloprovincialis involved the co-regulation of the MAPK-based and AMPK-based anti-inflammatory pathways. A. irradians bore a higher risk of death because it did not have the balance system, and the regulation of apoptosis-related pathways such as the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway were upregulated. Taken together, the regulation of the inflammatory balance coincides with the ability of bivalves to cope with PSTs. Inflammation is an important factor that affects the metabolic pattern of PSTs in bivalves. This study provides new evidence to support the studies on the resistance mechanism of bivalves to PSTs.

Keywords:

paralytic shellfish toxin; oxidative stress; inflammatory balance; Mytilus galloprovincialis; Argopecten irradians Key Contribution:

The differences in the detoxification of PSTs in M. galloprovincialis and A. irradians were evaluated and the significant changes involved MAPK and AMPK signaling pathways. JNK activation is consistent with the metabolism of PSTs and MAPK-mediated responses. Activation of the AMPK anti-inflammatory pathway results in stronger tolerance in M. galloprovincialis.

1. Introduction

Saxitoxin and its analogues (paralytic shellfish toxins, PSTs) are a type of shellfish toxin produced by dinoflagellates such as Alexandrium, Gymnodinium, and Pyrodinium in the marine environment. Among these, the Alexandrium species, which are known to produce paralytic shellfish toxins (PSTs), are the most widespread shellfish-contaminating biotoxins and have a worldwide distribution [1]. In China, toxic dinoflagellates that produce PSTs, such as A. catenella, A. tamarense and G. catenatum, etc., have been identified [2,3,4]. An outbreak of PSP occurred in April 2016 in Qinhuangdao, a city along the coast of the Bohai Sea, and the causative species of the poisoning incident was suspected to be a species of Alexandrium [5]. During a cruise in 2019 in Qinhuangdao, three isolates of Alexandrium were established by cyst germination, and all three strains had the same toxin profile consisting of gonyautoxins 1, 3, 4 (GTX1, 3, 4) and neosaxitoxin (NEO) [6].

Alexandrium exposure has a negative impact on survival and growth in some bivalve populations, by interfering with feeding activities and shell valve closure [7]. Alexandrium exposure can also produce histopathological lesions, inflammatory responses and impair immune responses in bivalves exposed to them [8,9]. Studies have demonstrated significant differences in the accumulation and elimination of PSTs among different bivalves [10,11]. Generally, mussels can accumulate high levels of toxins in a short time period but can also eliminate them rapidly [12]. The use of mussels as bioindicators has been well documented in monitoring due to their ability to accumulate high levels of environmental pollutants [13,14]. In contrast, relatively lower accumulation and long-term residues were observed in scallops [15]. Recent studies have demonstrated that toxin-triggered processes have dominant effects in shellfish compared with warming and acidification conditions [16]. Transcriptomics has become an important tool for studying the molecular mechanisms of bivalve resistance to toxins, and mussels are one of the more ideal experimental animals because of their high resistance characteristics [17,18], and the digestive tissue is proposed to be better for monitoring compared to the gill tissue [19]. The complexity of the transcriptome and the high degree of individual variability in characteristics were suggested by Gerdol et al. in their search for molecular markers of Alexandrium minutum in M. galloprovincialis [20]. However, there is a gap in our knowledge of the imbalance between hosts and PSTs in different bivalves. A cross-sectional comparison of growth, clearance rates and immunity of different shellfish exposed to PSTs-producing algae has been carried out [21,22,23]. In recent years, some studies have also conducted comparative transcriptome analyses for different shellfish species [24,25]. However, there is still a lack of data on the comparative transcriptomes of different shellfish species after exposure to PSTs.

Bivalves as invertebrates lack adaptive immunity and rely primarily on the innate immune system for their defense [26,27]. Inflammation is a form of innate immune response by living organisms to harmful stimuli. In marine bivalves, inflammation is a common defense mechanism [28]. Progress has been made in the study of bivalve immunity mechanisms via transcriptome analysis. Several pathways have been identified as being involved in the tolerance to various heterologous substances; these pathways include MAPK [29], CYP450 [30] and NF-κB [31], etc. Mitogen-activated protein kinases, as initiators of innate immunity by stress and inflammation [32], have been extensively connected with resistance to Vibrio infection [33] and PFOA exposure [34] in Mytilus edulis. Moreover, a successful acute inflammatory response results in the elimination of the infectious agents followed by a resolution and repair phase, indicating that anti-inflammatory factors are crucial for the transition from inflammation to resolution [35]. Mussel extracts (Perna viridis) have potential anti-inflammatory properties and have been marketed as nutraceuticals against arthritis [36]. As is well-known, acute stress typically decreases the function of the immune system, while prolonged stress causes an inflammatory response [37]. Our understanding of the roles of such processes in response to PST challenge is limited. Also, bottlenecks in transcriptomics applications that lack genomic databases for commercial bivalve species are gradually being overcome.

Since 2016, a recurring Alexandrium catenella bloom has occurred in Qinhuangdao [6], a city along the coast of the Bohai Sea. M. galloprovincialis was the cause of PST poisoning at a relatively high level of over 4.9 × 104 μg STX eq/kg in 2016. M. galloprovincialis and A. irradians are the main cultured species in this area. However, a previous study found that the exposure to PSTs caused large-scale mortality of bay scallops, while mussels were relatively unaffected (unpublished data). In order to examine the difference in resistance, we focused on inflammatory reactions. We exposed two shellfish species to PSTs during natural blooms from April to May and monitored the resulting content of PSTs. Samples from the elimination processes were collected for transcriptome analysis. The key pathways were revealed by comparing the stress differences between the two species from the same environment. The outcomes of this study will increase our understanding of bivalve–PSTs interactions and interspecific differences in the resistance to PSTs.

2. Results

2.1. Analysis of PSTs Accumulation and Metabolism

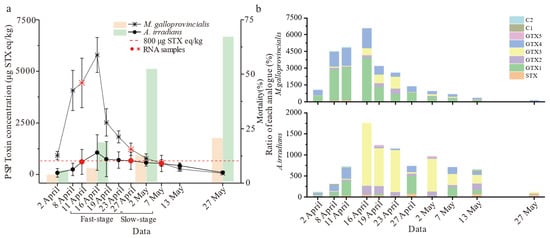

The shellfish collected from Qinhuangdao waters exposed to an Alexandrium catenatum red tide were examined by using the LC-MS/MS technique. During the experiment, the algal density of A. catenella was monitored as shown in Supplementary Materials, Table S1. The accumulation and elimination dynamics of PSTs were significantly different between M. galloprovincialis and A. irradians (p < 0.01) after toxigenic algae blooms (Figure 1a). PSTs accumulated at the highest level on 16 April and exceeded the safety limit (800 μg STX eq/kg), while toxin distributed in M. galloprovincialis was five times higher than in A. irradians, reaching 5604.8 μg STX eq/kg. The average accumulation and elimination rates of M. galloprovincialis reached 319.2 μg STX eq/kg/day and 129.2 μg STX eq/kg/day, respectively, which were up to five times higher than those of A. irradians (60.8 μg STX eq/kg/day and 22.8 μg STX eq/kg/day) during the same period. Indeed, the accumulation of toxins in the scallop was low, and there was no rapid metabolism of the toxins. There were also significant differences in the accumulation ratio of each analogue (Figure 1b). GTX1 was the main component in M. galloprovincialis, while GTX3 was dominant in A. irradians. For both species, the ratio of STX increased significantly with time. However, A. irradians showed abnormally high mortality (>50%) from the beginning of May. M. galloprovincialis displayed strong survivability and insensitivity to PSTs compared to A. irradians. According to the toxin elimination rate, we divided progress into fast (“Fast-stage”) and slow (“Slow-stage”) stages for transcriptome analysis.

Figure 1.

Results of PSTs accumulation in M. galloprovincialis and A. irradians. (a) The line graph represents the PSTs concentrations in M. galloprovincialis and A. irradians from 2 April to 27 May and the bar graphs characterize the mortality of M. galloprovincialis and A. irradians during the experiment. (b) Ratio of different PST analogues over time (the units for analogues content were converted to μg STX eq/kg). Notes: values are expressed as means ± SD of three replicate samples.

2.2. De Novo Assembly of Transcripts, Enrichment, and Annotation of Differential Genes

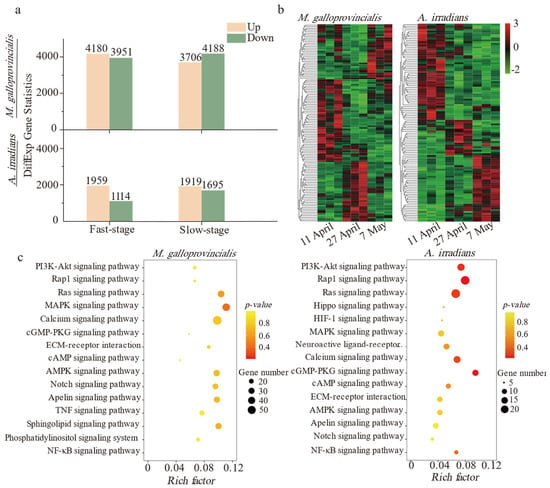

Trinity software was applied to complete the de novo assembly, and the assembled unigene sequences were compared to KEGG and GO databases by blastx for functional annotation. The results showed that 95,515 and 70,009 unigenes were assembled from 58,694,915 and 51,135,489 Illumina paired-end clean reads of all samples in M. galloprovincialis and A. irradians, respectively. The Q30 values in the samples were greater than 95% (Table S2). Over 42.2% of the unigenes were annotated by GO and KEGG functional classification (Table S3). The number of DEGs in M. galloprovincialis was about twice as many as those in A. irradians (Figure 2a). A number of differentially expressed genes were detected at three sampling points (Figure 2b). The top hits were in signal transduction pathways followed by metabolic and immune defense pathways in both bivalve species. Notably, up to 85% of the genes were related to inflammation-related signal transduction (Figure 2c) of immune defense pathways and that enrichment of RAS and MAPK signaling pathway was very significant. More KEGG enrichment pathways are shown in Table S4. Compared with M. galloprovincialis, the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, apoptosis, and phagosome-related pathways were only significantly enriched in A. irradians.

Figure 2.

Difference and enrichment analysis based on the KEGG database after PSTs exposure. (a) Histogram of differentially expressed genes of M. galloprovincialis and A. irradians in the Fast-stage and Slow-stage (DEGs are filtered by fold change ≥ 2 and p-value ≤ 0.05). (b) Thermogram of differentially expressed genes in M. galloprovincialis and A. irradians. Color intensities on the heatmap indicate relative expression levels (RPKM), with log-transformed (log2) expression values ranging from −2 to 3 (3 biological replicates were available for each time point). (c) Bubble diagram of significant enrichment pathways (fold change ≥ 2 and p-value ≤ 0.05) in the Fast-stage.

2.3. Mechanism of Inflammatory Responses Correlates with Elimination of PSTs

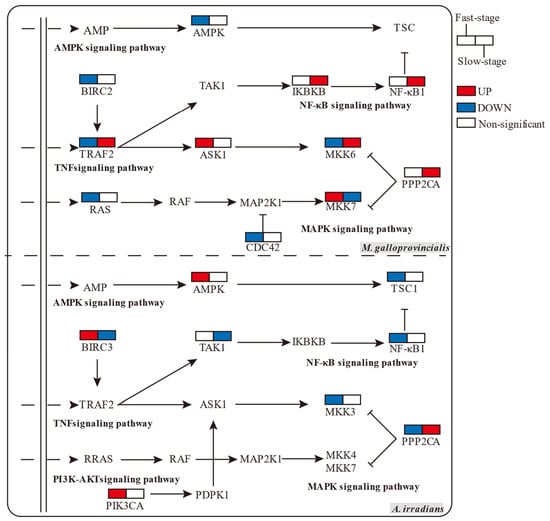

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA analysis) can successfully compensate for the lack of effective information mining of micro-effective genes by traditional enrichment analysis, and it can explain the regulatory role of a functional unit (KEGG pathway or others) more comprehensively. In this study, GSEA analysis identified MAPK as the core conjunction module with interspecific and temporal differences. The RAS, TNF, and NF-κB signaling pathways also acted in coordination with MAPK, as shown in Table 1. In M. galloprovincialis, MAPK-based pathways were significantly increased in the Slow-stage, but in A. irradians, TNF and NF-κB pathway was significantly up-regulated in the Fast-stage, while MAPK and TNF were significantly down-regulated in the Slow-stage. The analysis of specific genes showed that the high content of toxins led to more efficient expression of core genes. Relevant research has shown that MEK1/2, MKK4/7, and MKK3/6 are the core activators of JNK and p38 pathways (Figure 3). In M. galloprovincialis, upregulation of the JNK pathway appeared in the Fast-stage (MKK7) and down-regulation in the Slow-stage, which is consistent with the rule of toxin metabolism. The p38 pathway, in contrast, was complementary to JNK (MKK6). Genes related to the NF-κB pathway (NF-κB1 and IKBKB) were significantly upregulated in the Slow-stage of M. galloprovincialis; conversely, NF-κB1 was significantly down-regulated in the Fast-stage in A. irradians.

Table 1.

GSEA analysis parameters of the target pathways.

Figure 3.

Comparison of expression of core genes in inflammation-related enrichment signal pathways in M. galloprovincialis and A. irradians at the Fast-stage and Slow-stage (colored boxes represent genes significantly up- or down-regulated, p-value < 0.05).

Anti-inflammatory effects prevent the body from being excessively damaged by inflammation. In this study, we found that anti-inflammatory effects were present in two forms to maintain the balance of the host, i.e., internal inhibition regulation of the MAPK pathway and specialized genes in AMPK. Among them, the expression of AMPK pathway genes was down-regulated in the Fast-stage, significantly up-regulated in the Slow-stage in M. galloprovincialis, and not significantly down-regulated in A. irridians (Table 1). Analysis of related genes showed that the MAPK suppressor genes, such as CDC42 to JNK, were significantly down-regulated in M. galloprovincialis (Figure 3), and the AMPK pathway gene PPP2CA, which exerts anti-inflammatory effects, was significantly down-regulated in the Fast-stage in A. irradians, while in the Slow-stage we observed a consistent, significant upregulation in both species. In addition, the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway was related to the specific enrichment in A. irradians, showing a non-significant upregulation, and the gene PIK3CA was significantly upregulated in the Fast-stage.

2.4. Validation of Important DEGs Related to the Inflammatory Reaction Using qRT-PCR

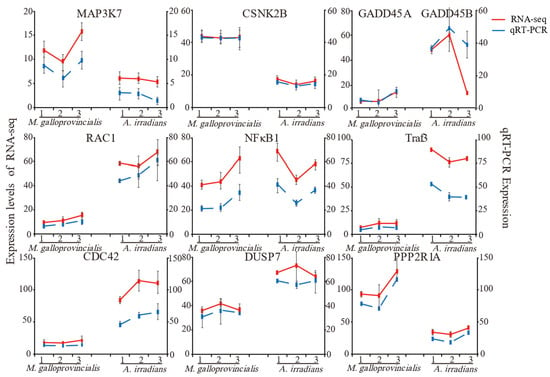

To confirm the results of RNA-Seq in this study, 10 common genes of M. galloprovincialis and A. irradians involved in MAPK, TNF, NF-κB, and AMPK signaling pathways were selected, and qRT-PCR was applied to examine the expression levels of these genes (Figure 4). Although these genes exhibited different expression patterns, the qPCR results were consistent with the RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) results at different timepoints, confirming the accuracy and reliability of the transcriptome sequencing data.

Figure 4.

Comparison of differentially expressed genes and qRT-PCR. Notes: The data are presented as mean ± SD of three parallel measurements.

3. Discussion

3.1. Differences in Physiological Characteristics between M. galloprovincialis and A. irradians under PSTs Stress

A limited number of studies have shown that the ability to accumulate PSTs between M. galloprovincialis and A. irradians was significantly different. Some studies have shown that after exposure to A. catenella at a density of 5.6 × 106 cells/mL, the concentration of PSTs in Mytilus coruscus was 1864 μg/kg (the regular standard is 800 μg/kg) [38]. After exposure to A. tamarense at a density of 1.26 × 104 cells/mL, the concentration in A. irradians was 49.4 MU/g (the regular standard is 4 MU/g) [39]. It seemed that A. irradians had stronger accumulation ability, but this could not be determined due to different environmental conditions. Therefore, M. galloprovincialis and A. irradians were placed in the same environment for experiments in this study. The opposite result appeared in our study, i.e., M. galloprovincialis exhibited higher PSTs tolerance as well as a stronger ability to accumulate and metabolize PSTs. In contrast, the slow metabolism and high mortality rate of A. irradians indicated weaker adaptability to the stress.

In this study, PSTs distributed in M. galloprovincialis were five times higher than in A. irradians, reaching 5604.8 μg STX eq/kg. This may be caused by the individual specificity of the PSTs exposure of the two shellfish, and some studies support this conjecture. Studies have shown that the axons of M. galloprovincialis neurons were insensitive to STX [40], so they can accumulate toxins more quickly and in higher amounts than other species. Limited studies have shown that A. irradians is very sensitive to PSTs, leading to shell closure and reduced food intake [41].

PSTs induce oxidative stress, paralysis, and immune impairment of bivalves [40]. In this study, the two showed different physiological stress responses. As shown by KEGG pathway analysis, the bivalves presented both innate immune and inflammatory responses against PSTs exposure. However, there were differences in the pathways and genes between the two. The number of differential genes in M. galloprovincialis was two times higher than in A. irradians, which may be related to their pan-genome [42]. This implies that the large number of differential genes includes many dispensable genes in addition to the core genes. Due to the extreme intraspecific genetic diversity within M. galloprovincialis, it is expected that some of the differential genes were not related to the response to PSTs accumulation, but constitute background noise. However, it has also been proposed that accessory functions provided by the large number of dispensable genes may underpin the improved ability to adapt to challenging and varying environmental conditions [42]. The published data indicate that M. galloprovincialis displays adaptive traits to maintain immune capacity upon prolonged PSTs exposure, including a selective evolutionary advantage [43] and the enhancement of detoxification and antioxidant defense systems [44]. In contrast, the immune system of A. irradians displayed negative effects when faced with the same stress [45], as immuno-depleted, chronic [46], and uncontrolled inflammation caused persistent tissue damage [47]. In summary, accumulative metabolism and mortality reflect differences in external physiological characteristics, and M. galloprovincialis present stronger immune responses to PSTs exposure.

3.2. Interference-Specific Differences in Inflammation between M. galloprovincialis and A. irradians under PSTs Stress

Available data on bivalve immunity through the omics approach have only been obtained in the last few years. The inflammatory response is likely to be involved in repairing damaged tissues [48] and in detoxification [9]. These responses are time-, species-, and concentration-dependent [49]. Our results showed that there was a relatively complete inflammatory regulation system involving MAPK pathways in M. galloprovincialis but not in A. irradians. This is related to the stronger antioxidant capacity of mussels in the early stages [50]. In the Slow-stage, the extraordinary contribution of JNK/P38 revealed a dramatic inflammatory response in M. galloprovincialis. JNK activation is a key determinant in the cellular response. The activation of the JNK pathway was consistent with the metabolic rule of PSTs. Some researchers have suggested that JNK plays an active role in toxin stress [51].

In contrast, A. irradians displayed immunosuppression after exposure to shellfish toxins such as okadaic acid [52], domoic acid [53], and micropolystyrene [54]. In this study, the expression of inflammation-related genes of A. irradians showed non-significant and significant inhibition, which may indicate the immunosuppression of A. irradians against PSTs as well, but the immunosuppression indicators still need to be measured. Continuous upregulation of signal transduction activated the NF-κB1 in the Slow-stage of M. galloprovincialis, while this pathway was significantly down-regulated in the Fast-stage in A. irradians. Therefore, the two species are diametrically opposite in terms of cell survival and apoptosis regulation. Therefore, an unexpected finding was that the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway was significantly upregulated in the transcriptome of A. irradians at the Slow-stage. Additionally, the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway has previously been shown to have a synergistic effect with MAPK in promoting the inflammatory reaction [55]. To summarize, PST-induced metabolic disorders are likely to increase susceptibility to pathogens by physiologically weakening bivalves and interfering with immune functions for tissue repair [1].

3.3. Importance of Adjusting the Immune Balance between Inflammation and Anti-Inflammatory Effects

In model organisms such as shellfish, the inflammatory balance reaction [56,57] is one of the main pathways affecting metabolism and autophagy. In this study, factors such as PPP2R1A were significantly expressed in M. galloprovincialis, suggesting that AMPK could inhibit MAPK. The metabolic regulation process of mussels for toxins is more diversified. As a result of the self-limitation of the p38 MAPK signaling pathway and activation of the AMPK signaling pathway to inhibit the MAPK/NF-κB pathway, damage to the body of the mussel is significantly reduced through a dynamic balance. Studies have also confirmed the presence of stress-memory in M. galloprovincialis involving different responses at different times and eventual survival, such as from inflammation to control and resolve the inflammatory response and avoid subsequent cellular death and DNA damage after infection with Vibrio splendidus. The combination of a complex genome with the adaptation of the mussel immune system to a changing environment could explain this high variability [42,43]. The internal regulation of the MAPK pathway and the exogenous resistance regulation of AMPK can reflect the fatigue in the stress response of mussels. This includes the slowing of toxin metabolism and the adaptive down-regulation of the inflammatory response.

Novel insights into the specificity of AMPK signaling complexes have been gained [58]. Studies have confirmed the inhibitory effect of AMPK on inflammatory pathways such as JAK-STAT [59] and NF-κB [60]. The role of AMPK linked with various anti-inflammatory signals to limit the inflammatory response has been widely confirmed [61]. In M. galloprovincialis, this signaling pathway forms a perfect balance with MAPK to control damage to the body. In contrast, the stress response of MAPK was relatively weak in A. irradians, and its balance regulation was self-limited, not via AMPK. We believe that this inflammatory balance system was closely related to the dominant physiological characteristics and immune advantages of M. galloprovincialis. However, A. irradians experienced higher mortality without such balanced regulation. In contrast, this unbalanced regulation simultaneously enables cells to overcome metabolic stress by inhibiting AMPK signaling [61], a key singular node of cellular metabolism in A. irradians. AMPK and PI3K-AKT are involved in the regulation of metabolites such as glucose. Therefore, we believe that the detoxifying system of A. irradians is more inclined to cellular metabolizing and apoptosis than toward inflammation regulation and self-protection.

This is the first study to evaluate the differences in detoxification mechanisms for paralytic shellfish toxin in M. galloprovincialis and A. irradians under natural algal bloom conditions. In order to explain the stress response difference between the two shellfish in the process of toxin metabolism, we divided the process into two metabolic stages. However, due to the long time span of the sampling, we could not accurately determine the activation time of AMPK, and thus further detailed research is needed. A. irradians exhibited high mortality, and although we were able to ensure that the experiments were conducted in sufficient numbers, A. irradians were taken alive and did not accurately reflect the condition of the large number of dead scallops. We mainly used the KEGG database for data analysis, which is strongly biased towards model organisms. The vast majority of bivalve genes only show limited sequence homology with sequences with a known function, which can often lead to incorrect annotations, and the signaling pathways in bivalves are not necessarily identical to those found in other organisms. In addition, autophagy and tissue damage are also common features in shellfish exposed to PSTs, although no relevant experiments were performed in this study.

4. Conclusions

An effective immune response is indispensable for growth, reproduction, and survival. In this study, we comprehensively compared transcription and physiological responses to examine the inflammatory–anti-inflammatory balance mechanisms in M. galloprovincialis and A. irradians under PSTs exposure. The significant changes found involved MAPK and AMPK signaling pathways and the specific regulatory pathway, PI3K-AKT. JNK and p38 MAPK activate the MAPK pathway in M. galloprovincialis. Meanwhile, there was significant expression of inhibitor genes, including TNF, NF-κB, and AMPK, especially during the slow metabolic phase. Therefore, an intense inflammatory reaction and a corresponding anti-inflammatory reaction in M. galloprovincialis constituted a relatively effective mechanism for high-filtering activity and low-tissue damage after PSTs exposure. However, A. irradians focused on the regulation of downstream cell metabolism and apoptosis, and thus the immune imbalance resulted in serious tissue damage and high mortality. In summary, there were clear differences in the metabolic patterns related to PSTs in M. galloprovincialis and A. irradians. Inflammation is an important factor that affects the metabolic pattern of PSTs in bivalves.

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Sample Collection and Preparation

The exposure experiment was conducted in the Qinhuangdao coastal culture area (39.94211° N, 119.73559° E). One-year-old M. galloprovincialis (shell length: 46 mm ± 3.8 mm) and A. irradians (shell length: 65 ± 4.0 mm) were cultured in shell breeding cages under surface seawater (depth: 10 m) from January 2019. An Alexandrium catenella red tide was observed from 29 March until 13 May (<200 cells/L), with the highest density at 3.40 × 103 cells/L. From 2 April, sampling was performed every 3–6 days (depending on the sea conditions). Six biological replicates (PSTs accumulation × 3 and RNA-seq × 3) were collected each time, and each biological replicates contained 3–5 units. Three groups sampled on 11 April, 27 April, and 7 May were chosen for transcriptomics research. Shellfish hepatopancreas was collected on ice, washed with normal saline, and drained of surface water. All samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Samples for sequencing were stored at −80 °C, whereas the samples for PSTs concentration measurements were stored at −20 °C until further analysis.

5.2. Determination of PSTs Accumulation

Five grams of each sample was weighed into a 50 mL centrifuge tube after mixing with a homogenizer (T18, IKA, Staufen, Germany), and 5 mL of 1% acetic acid aqueous solution was added for extraction. After vortexing for 10 min, the mixture was heated using a boiling water bath for 5 min and allowed to cool to room temperature in flowing water. The samples were centrifuged at 10,000× g for 5 min, and 1 mL of the supernatant was removed and adjusted for pH by 5 µL ammonium hydroxide, then centrifugation for 10 min at 16,000× g for purification of solid-phase extraction (SPE). ENVI-Carb cartridges (250 mg, 3 mL, Supelco, Bellefonte, PA, USA) were activated with 3 mL acetonitrile, 3 mL 20% acetonitrile aqueous solution (containing 1% acetic acid), and 3 mL 0.1% ammonium hydroxide. After activation, 500 µL of the supernatant was added, and 700 µL ultrapure water was used for elution. Finally, 1 mL 75% acetonitrile solution (containing 0.25% formic acid) was used for elucidation. All samples were filtered through 0.22 μm syringe filters.

5.3. LC-MS/MS Analysis

LC-MS/MS analysis of the PSTs was performed using an HPLC system (LC-20ADXR, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) coupled to a hybrid triple quadrupole linear ion trap mass spectrometer (5500 QTRAP, AB Sciex, Boston, MA, USA). PSTs were screened using the multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) method for the separation of toxins using a hydrophilic column (TSK-Amide-80, 150 mm × 2.0 mm, 3 µm particle size) [62]. The PSTs standards, including C1 and 2, GTX2 and 3, GTX1 and 4, GTX5, and STX were purchased from the National Research Council of Canada. Thirteen PSTs standards diluted to 100 μg/mL were implemented as quality controls (QC) in the analytical runs (Tables S5–S7).

5.4. RNA Extraction, Library Construction, and Sequencing Analysis

The hepatopancreas of shellfish were used for RNA extraction. RNA extraction and transcriptomic sequencing were performed by Gene Denovo, Guangzhou. The mRNA was enriched by Oligo (dT) beads. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSeqTM 4000 platform. The paired-end sequencing with a 2 × 150 bp approach was applied. A total of 18 libraries were established (including 2 species × 3 time points × 3 biological replicates). Clean data were produced by removing adaptor sequences, unknown nucleotides (>10%), and low-quality sequences (Q-value ≤ 10) from the raw data for subsequent analyses. Then, transcriptome de novo assembly was carried out with the short reads assembling program Trinity. For each transcript, an FPKM value was calculated to quantify its expression abundance and variation using RSEM software. The unigene expression was calculated and normalized to RPKM (Reads Per kb per Million reads). Raw sequencing data has been uploaded to NCBI and the relevant accession numbers are PRJNA850029 and PRJNA850516.

5.5. Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) Analysis

Differential expression analysis was performed using DESeq2 software. The read count was first normalized, and then the probability of hypothesis testing (p-value) was calculated according to the model. Finally, multiple hypothesis tests were performed to correct the FDR values. We conducted two-by-two comparisons for the sampling groups 11 April, 27 April, and 7 May, respectively, where we set 11 April to 27 April as the Fast-stage and 27 April to 7 May as the Slow-stage. Based on the results of analysis of variance, genes with p-value < 0.05 and |log2FC| > 1 were screened as significantly different genes. GOseq software was used to annotate the GO functions in order to reveal the biological functions of the differentially expressed genes; KEGG was used to analyze the signal pathways involving the genes. A threshold-corrected p-value < 0.05 was used to determine the significance of differences in GO and KEGG annotations of DEGs. Moreover, we performed gene set enrichment analysis using the software GSEA and MSigDB to identify whether a set of genes in a specific KEGG pathway showed significant differences between the two groups. Significantly enriched gene sets were defined as those with normalized enrichment score (NES) > 1 and p-value < 0.05.

5.6. Validation of Gene Expression by qRT-PCR

To validate the reliability of our transcriptome sequencing data, 12 DEGs of M. galloprovincialis and A. irradians were selected and analyzed by qRT-PCR. We selected eight common primers, TRAF3, MAP3K7, NF-κB1, CDC42, RAC1, PPP2R1A, CSNK2B, DUSP7, and four characteristic primers, JUN and GADD45B in M. galloprovincialis and BIRC2 and GADD45A in A. irradians. The primers and reference genes are listed in Supplementary Table S8.

The total reaction volume of 20 μL contained 4 μL 4× gDNA wiper Mix, 2 μL of total RNA, 4 μL of 5× HiScript‖qRT SuperMix‖, and 10 μL of RNase-Free ddH2O. The amplification profile was as follows: denaturation at 95 °C for 90 s followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s, 60 °C for 15 s, and 72 °C for 20 s as described previously. The GAPDH gene was chosen as a reference gene. Relative mRNA expression was determined using the 2−ΔΔCT method.

5.7. Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS version 16.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Two-tailed Student’s t-tests were used to analyze differences among treatments. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05. All data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/toxins14080516/s1, Table S1: Distribution dynamics of Alexandrium catenella cells; Table S2: Summary of transcriptome sequencing; Table S3: Summary of reads annotation; Table S4: KEGG enrichment results of TOP30; Table S5: Results of toxin concentration (μg STX eq/kg); Table S6: Concentration of mixed standard solution; Table S7: Results of quality control; Table S8: PCR primer list.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.T.; Formal analysis, G.Z. and M.G.; funding acquisition, Z.T.; investigation, G.Z. and J.P.; methodology, H.W.; project administration, Z.T.; resources, M.G.; supervision, Z.T.; validation, J.P.; visualization, C.D.; writing—original draft, C.D. and H.W.; writing—review and editing, C.D. and H.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2017YFC1600701), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32072329, 31772075), and Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund, CAFS (No. 2020TD71). We thank LetPub (www.letpub.com) for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

RNA-seq raw sequencing data has been uploaded to NCBI’s Sequence Read Archive (SRA) and the relevant accession numbers are PRJNA850029 and PRJNA850516.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lassudrie, M.; Hégaret, H.; Wikfors, G.H.; Silva, P. Effects of marine harmful algal blooms on bivalve cellular immunity and infectious diseases: A review. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2020, 108, 103660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, C.; Ye, R.-M.; Zheng, J.-W.; Luo, Z.-H.; Gu, H.-F.; Yang, W.-D.; Li, H.-Y.; Liu, J.-S. Molecular phylogeny and PSP toxin profile of the Alexandrium tamarense species complex along the coast of China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 89, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, H.; Liu, T.; Vale, P.; Luo, Z. Morphology, phylogeny and toxin profiles of Gymnodinium inusitatum sp. nov., Gymnodinium catenatum and Gymnodinium microreticulatum (Dinophyceae) from the Yellow Sea, China. Harmful Algae 2013, 28, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.Z.; Lin, L.; Gu, H.F.; Chan, L.L.; Hong, H.S. Comparative studies on morphology, ITS sequence and protein profile of Alexandrium tamarense and A catenella isolated from the China Sea. Harmful Algae 2008, 7, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Qiu, J.; Li, A. Proposed biotransformation pathways for new metabolites of paralytic shellfish toxins based on field and experimental mussel samples. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 5494–5502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.C.; Zhang, Q.C.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Z.F.; Zhou, M.J. The dinoflagellate Alexandrium catenella producing only carbamate toxins may account for the seafood poisonings in Qinhuangdao, China. Harmful Algae 2021, 103, 101980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andres, J.K.; Yñiguez, A.T.; Maister, J.M.; Turner, A.D.; Olano, D.E.B.; Mendoza, J.; Salvador-Reyes, L.; Azanza, R.V. Paralytic shellfish toxin uptake, assimilation, depuration, and transformation in the southeast Asian green-lipped mussel (Perna viridis). Toxins 2019, 11, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, G.A.; Cmb, C.; Qi, L. Effects of toxic dinoflagellate Alexandrium catenella on sexual maturation and reproductive output in the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas. Aquat. Toxicol. 2021, 232, 105745. [Google Scholar]

- Galimany, E.; Sunila, I.; Hégaret, H.; Ramón, M.; Wikfors, G.H. Pathology and immune response of the blue mussel (Mytilus edulis L.) after an exposure to the harmful dinoflagellate Prorocentrum minimum. Harmful Algae 2008, 7, 630–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Kong, F.-Z.; Xun, X.-G.; Dai, L.; Geng, H.-X.; Hu, X.-L.; Yu, R.-C.; Bao, Z.-M.; Zhou, M.-J. Biokinetics and biotransformation of paralytic shellfish toxins in different tissues of Yesso scallops, Patinopecten yessoensis. Chemosphere 2020, 261, 128063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mjba, B.; Fm, A.; Rf, C.; Ap, C.; Ep, D.; Cv, B. Paralytic shellfish toxin profiles in mussel, cockle and razor shell under post-bloom natural conditions: Evidence of higher biotransformation in razor shells and cockles. Mar. Environ. Res. 2020, 154, 104839. [Google Scholar]

- Vale, P. Metabolites of saxitoxin analogues in bivalves contaminated by Gymnodinium catenatum. Toxicon 2010, 55, 162–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Sun, C.; He, C.; Li, J.; Ju, P.; Li, F. Microplastics in four bivalve species and basis for using bivalves as bioindicators of microplastic pollution. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 782, 146830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strehse, J.S.; Maser, E. Marine bivalves as bioindicators for environmental pollutants with focus on dumped munitions in the sea: A review. Mar. Environ. Res. 2020, 158, 105006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comeau, L.A.; Babarro, J.M.; Riobó, P.; Scarratt, M.; Starr, M.; Tremblay, R. PSP-producing dinoflagellate Alexandrium minutum induces valve microclosures in the mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis. Aquaculture 2019, 500, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, A.C.; Pereira, V.; Marçal, R.; Marques, A.; Guilherme, S.; Costa, P.R.; Pacheco, M. DNA damage and oxidative stress responses of mussels Mytilus galloprovincialis to paralytic shellfish toxins under warming and acidification conditions—Elucidation on the organ-specificity. Aquat. Toxicol. 2020, 228, 105619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prego-Faraldo, M.V.; Martínez, L.; Méndez, J. RNA-seq analysis for assessing the early response to DSP toxins in Mytilus galloprovincialis digestive gland and gill. Toxins 2018, 10, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pazos, A.J.; Ventoso, P.; Martínez-Escauriaza, R.; Pérez-Parallé, M.L.; Blanco, J.; Triviño, J.C.; Sánchez, J.L. Transcriptional response after exposure to domoic acid-producing Pseudo-nitzschia in the digestive gland of the mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis. Toxicon 2017, 140, 60–71. [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Ulloa, V.; Fernandez-Tajes, J.; Aguiar-Pulido, V.; Prego-Faraldo, M.V.; Eirin-Lopez, J.M. Unbiased high-throughput characterization of mussel transcriptomic responses to sublethal concentrations of the biotoxin okadaic acid. PeerJ 2015, 3, e1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gerdol, M.; De Moro, G.; Manfrin, C.; Milandri, A.; Riccardi, E.; Beran, A.; Venier, P.; Pallavicini, A. RNA sequencing and de novo assembly of the digestive gland transcriptome in Mytilus galloprovincialis fed with toxinogenic and non-toxic strains of Alexandrium minutum. BMC Res. Notes 2014, 7, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qiu, J.B. Metabolic Transformation and Physiological and Biochemical Response of Bivalves to Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning; Ocean University of China: Qingdao, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Leverone, J.R.; Shumway, S.E.; Blake, N.J. Comparative effects of the toxic dinoflagellate Karenia brevis on clearance rates in juveniles of four bivalve molluscs from Florida, USA. Toxicon 2007, 49, 634–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeveroneÃ, J.R.; Blake, N.J.; Pierce, R.H.; Shumway, S.E. Effects of the dinoflagellate Karenia brevis on larval development in three species of bivalve mollusc from Florida. Toxicon 2006, 48, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, W.; Rui, H.; Bao, Z.; Du, H.; He, Y.; Su, H.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, X.; Jiao, W.; Li, Y. Transcriptome sequencing of zhikong scallop (Chlamys farreri) and comparative transcriptomic analysis with yesso scallop (Patinopecten yessoensis). PLoS ONE 2013, 8, 63927. [Google Scholar]

- Lk, A.; Cbb, C.; Tb, C.; Vs, D.; Mhde, F.; Fm, B.; Hs, A. Comparative de novo assembly and annotation of mantle tissue transcriptomes from the Mytilus edulis species complex (M. edulis, M. galloprovincialis, M. trossulus). Mar. Genom. 2020, 51, 100700. [Google Scholar]

- Song, L.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Wang, M. The immune system and its modulation mechanism in scallop. Fish Shellfish. Immunol. 2015, 46, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, G.; Venier, P. An updated molecular basis for mussel immunity. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2015, 46, 17–38. [Google Scholar]

- Shk, A.; Kwn, A.; Ba, B.; Ksc, C.; Khp, A.; Kip, A. Quantification of the inflammatory responses to pro-and anti-Inflammatory agents in manila clam, Ruditapes philippinarum. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2021, 115, 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ugo, M.; Sergiy, K.; Baldur, S. The role of mitogen-activated protein kinase-activated protein kinases (MAPKAPKs) in inflammation. Genes 2013, 4, 101–133. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.; Lu, M.; Duan, G.; Li, H.; Liu, J.; Yang, W. Responses of CYP450 in the mussel Perna viridis after short-term exposure to the DSP toxins-producing dinoflagellate Prorocentrum lima. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 176, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.A.; Yu, Z.A.; Ht, A.; Zz, A.; Hz, B.; Fh, A.; Fy, A. Macrophage immunomodulatory effects of low molecular weight peptides from Mytilus coruscus via NF-κB/MAPK signaling pathways. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 83, 104562. [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakis, J.M.; Avruch, J. Mammalian MAPK signal transduction pathways activated by stress and inflammation: A 10-year update. Physiol. Rev. 2012, 92, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chovatiya, R.; Medzhitov, R. Stress, inflammation, and defense of homeostasis. Mol. Cell 2014, 54, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, F.; Yu, Y.; Guo, M.; Lin, Y.; Tan, Z. Integrated analysis of physiological, transcriptomics and metabolomics provides insights into detoxication disruption of PFOA exposure in Mytilus edulis. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 214, 112081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medzhitov, R. Review article origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature 2008, 454, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, K.; Joy, M. High-value compounds from the molluscs of marine and estuarine ecosystems as prospective functional food ingredients: An overview. Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, 109637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C. Stress, inflammation, and autoimmunity: The 3 modern erinyes. Clin. Ther. 2020, 42, 742–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Fan, C.; Shen, X. Combined effects of temperature and toxic algal abundance on paralytic shellfish toxic accumulation, tissue distribution and elimination dynamics in mussels Mytilus coruscus. Toxins 2021, 13, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, C.; Guo, H.; Jiao, X.; Zhao, W. Studies on the time of accumulation and elimination of Alexandrium tamarense toxins in Argopectens irradias. J. Earth. Sci.-China 2012, 2, 112–117. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, V.A.; Langeloh, H.; Tillmann, U.; Krock, B.; Müller, A.; Bickmeyer, U.; Abele, D. Separate and combined effects of neurotoxic and lytic compounds of Alexandrium strains on Mytilus edulis feeding activity and hemocyte function. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019, 84, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yan, T.; Zhou, M.; Fu, M.; Yu, R.; Wang, Y.; Li, J. Effects of the dinoflagellate Alexandrium tamarense on early development of the scallop Argopecten irradians concentricus. Aquaculture 2003, 217, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdol, M.; Moreira, R.; Cruz, F.; Gómez-Garrido, J.; Figueras, A. Massive gene presence-absence variation shapes an open pan-genome in the Mediterranean mussel. Genome Biol. 2020, 21, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueras, A.; Moreira, R.; Sendra, M.; Novoa, B. Genomics and immunity of the mediterranean mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis in a changing environment. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019, 90, 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappello, T.; Maisano, M.; D’Agata, A.; Natalotto, A.; Mauceri, A.; Fasulo, S. Effects of environmental pollution in caged mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis). Mar. Environ. Res. 2013, 91, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.; Giri, S.S.; Jun, J.W.; Yun, S.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, S.G.; Park, S.C. Immune response of the bay scallop, Argopecten irradians, after exposure to the algicide palmitoleic acid. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2016, 57, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.; Giri, S.S.; Jun, J.W.; Kim, H.J.; Yun, S.; Kim, S.G.; Park, S.C. Marine toxin okadaic acid affects the immune function of bay scallop (Argopecten irradians). Molecules 2016, 21, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chi, C.; Zhang, C.; Liu, J.; Zheng, X. Effects of marine toxin domoic acid on innate immune responses in bay scallop Argopecten irradians. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2019, 7, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hermabessiere, L.; Fabioux, C.; Lassudrie, M.; Boullot, F.; Long, M.; Lambert, C.; Le Goïc, N.; Gouriou, J.; Le Gac, M.; Chapelle, A.; et al. Influence of gametogenesis pattern and sex on paralytic shellfish toxin levels in triploid Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas exposed to a natural bloom of Alexandrium minutum. Aquaculture 2016, 455, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chi, C.; Giri, S.S.; Jun, J.W.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, S.W.; Yun, S.; Park, S.C. Effects of algal toxin okadaic acid on the non-specific immune and antioxidant response of bay scallo(Argopecten irradians. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2017, 65, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.B.; Ma, F.; Fan, H.; Li, A. Effects of feeding Alexandrium tamarense, a paralytic shellfish toxin producer, on antioxidant enzymes in scallops (Patinopecten yessoensis) and mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis). Aquaculture 2013, 396–399, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagahama, M.; Shibutani, M.; Seike, S.; Yonezaki, M.; Takagishi, T.; Oda, M.; Kobayashi, K.; Sakurai, J. The p38 MAPK and JNK pathways protect host cells against clostridium perfringens beta-toxin. Infect. Immun. 2013, 81, 3703–3708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chi, C.; Giri, S.S.; Jun, J.W.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, S.W.; Kang, J.W.; Park, S.C. Detoxification and immune transcriptomic response of the gill tissue of bay scallop (Argopecten irradians) following exposure to the algicide palmitoleic acid. Biomolecules 2018, 8, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chi, C.; Yun, S.; Giri, S.S.; Kim, H.J.; Kang, J.W.; Park, S.C. Effect of the algicide thiazolidinedione 49 on immune responses of bay scallop Argopecten Irradians. Molecules 2019, 24, 3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Song, J.A.; Choi, C.Y.; Park, H. Exposure of bay scallop Argopecten irradians to micro-polystyrene: Bioaccumulation and toxicity. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2020, 236, 108801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Lin, C.; Chen, H.; Lin, J.; Cheng, Y.; Kao, S. AMPK activation inhibits expression of proinflammatory mediators through downregulation of PI3K/p38 MAPK and NF-κB signaling in murine macrophages. DNA Cell Biol. 2015, 34, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouallegui, Y. Immunity in mussels: An overview of molecular components and mechanisms with a focus on the functional defenses. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019, 89, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, A.; Novoa, B.; Figueras, A. The complexity of apoptotic cell death in mollusks: An update. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2015, 46, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardie, D.G.; Schaffer, B.E.; Brunet, A. AMPK: An energy-sensing pathway with multiple inputs and outputs. Trends Cell Biol. 2015, 26, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rutherford, C.; Speirs, C.; Williams, J.J.L.; Ewart, M.-A.; Mancini, S.J.; Hawley, S.A.; Delles, C.; Viollet, B.; Costa-Pereira, A.P.; Baillie, G.S.; et al. Phosphorylation of Janus kinase 1 (JAK1) by AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) links energy sensing to anti-inflammatory signaling. Sci. Signal. 2016, 9, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Qiu, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, M. AMP-activated protein kinase suppresses endothelial cell inflammation through phosphorylation of transcriptional coactivator. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011, 31, 2897–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yuan, J.; Dong, X.; Yap, J.; Hu, J. The MAPK and AMPK signalings: Interplay and implication in targeted cancer therapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Guo, M.; Bing. X.; Zheng. G.; Peng. J.; Tan. Z.; Zhai. Y. Simultaneous identification and detection of paralytic shellfish toxin in bivalve mollusks by liquid chromatography coupled with quadrupole/linear ion trap tandem mass apectrometry. Oceanol. Limnol. Sin. 2017, 48, 623–632. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).