Effects of Popular Diets without Specific Calorie Targets on Weight Loss Outcomes: Systematic Review of Findings from Clinical Trials

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

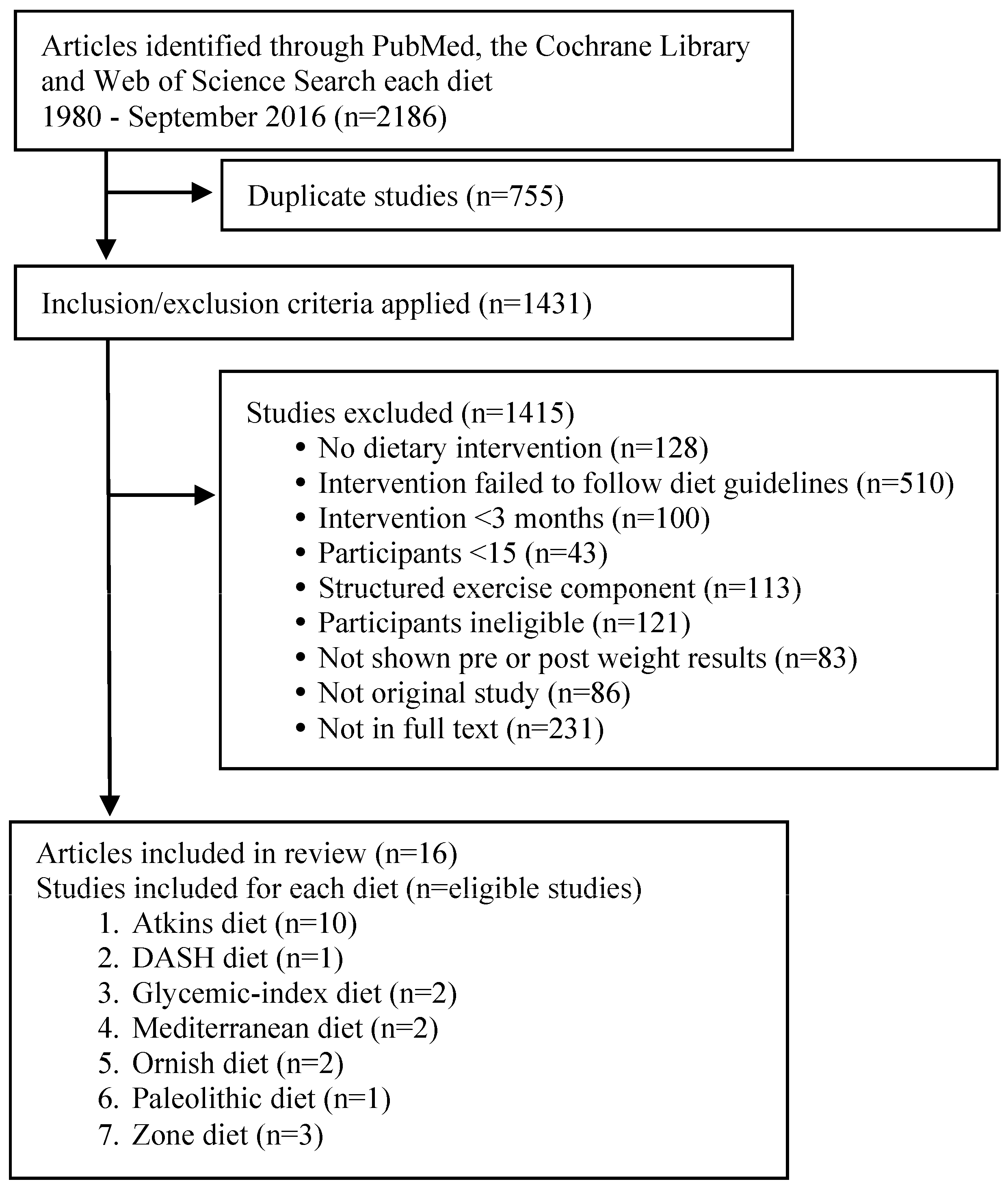

2.4. PubMed Search and Study Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Assessing Risk of Bias

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Risk of Bias

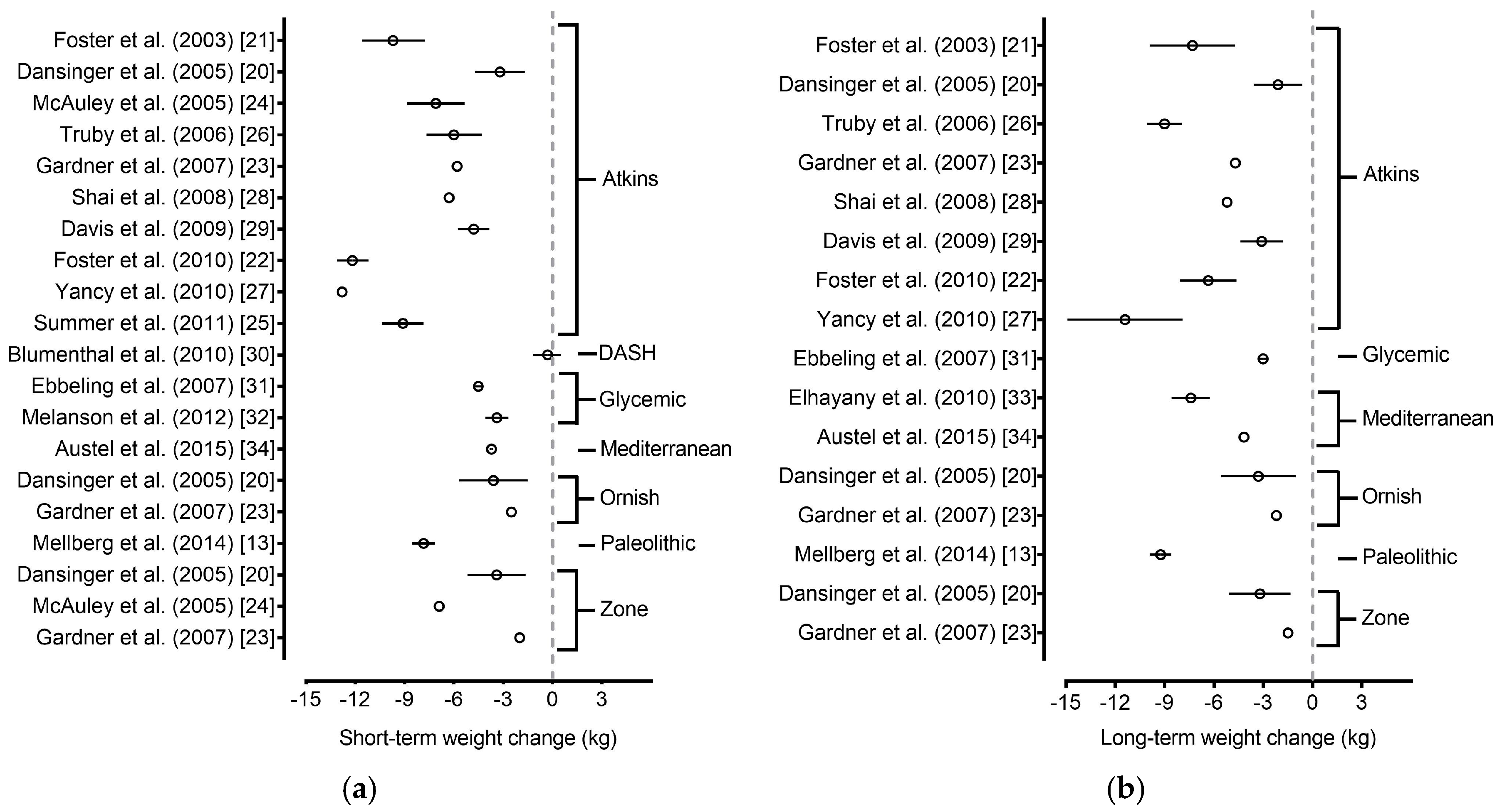

3.4. Main Findings

3.4.1. Atkins Diet

3.4.2. Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) Diet

3.4.3. Glycemic-Index Diet

3.4.4. Mediterranean Diet

3.4.5. Ornish Diet

3.4.6. Paleolithic Diet

3.4.7. Zone Diet

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mann, T.; Tomiyama, A.J.; Westling, E.; Lew, A.M.; Samuels, B.; Chatman, J. Medicare’s search for effective obesity treatments: Diets are not the answer. Am. Psychol. 2007, 62, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, B.C.; Kanters, S.; Bandayrel, K.; Wu, P.; Naji, F.; Siemieniuk, R.A.; Ball, G.D.; Busse, J.W.; Thorlund, K.; Guyatt, G.; et al. Comparison of weight loss among named diet programs in overweight and obese adults: A meta-analysis. JAMA 2014, 312, 923–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 7th ed.; Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2010.

- Cohen, E.; Cragg, M.; deFonseka, J.; Hite, A.; Rosenberg, M.; Zhou, B. Statistical review of US macronutrient consumption data, 1965–2011: Americans have been following dietary guidelines, coincident with the rise in obesity. Nutrition 2015, 31, 727–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makris, A.; Foster, G.D. Dietary approaches to the treatment of obesity. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2011, 34, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, R.E. Popular weight loss diets. Clin. Sports Med. 1999, 18, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, S.L. Popular weight reduction diets. J. Cardiovasc. Nurses 2006, 21, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, R. Dr. Atkins’ New Diet Revolution; Harper Collins: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Appel, L.J.; Moore, T.J.; Obarzanek, E.; Vollmer, W.M.; Svetkey, L.P.; Sacks, F.M.; Bray, G.A.; Vogt, T.M.; Cutler, J.A.; Windhauser, M.M.; et al. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997, 336, 1117–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, D.J.; Wong, J.M.; Kendall, C.W.; Esfahani, A.; Ng, V.W.; Leong, T.C.; Faulkner, D.A.; Vidgen, E.; Paul, G.; Mukherjea, R.; et al. Effect of a 6-month vegan low-carbohydrate (‘Eco-Atkins’) diet on cardiovascular risk factors and body weight in hyperlipidaemic adults: A randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e003505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebbeling, C.B.; Ludwig, D.S. Dietary approaches for obesity treatment and prevention in children and adolescents. In Handbook of Pediatric Obesity: Epidemiology, Etiology and Prevention; Goran, M.I., Sothern, M.S., Eds.; Marcel Dekker Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ornish, D. Eat More, Weigh Less; Harper Collins: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mellberg, C.; Sandberg, S.; Ryberg, M.; Eriksson, M.; Brage, S.; Larsson, C.; Olsson, T.; Lindahl, B. Long-term effects of a Palaeolithic-type diet in obese postmenopausal women: A 2-year randomized trial. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 68, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner-McGrievy, G.M.; Davidson, C.R.; Wingard, E.E.; Wilcox, S.; Frongillo, E.A. Comparative effectiveness of plant-based diets for weight loss: A randomized controlled trial of five different diets. Nutrition 2015, 31, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sears, B.; Lawren, W. Enter the Zone; Harper Collins: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- The Best Diet Rankings 2016—The Best Weight-Loss Diets, U.S. News & World Report L.P. Available online: http://health.usnews.com/best-diet/best-weight-loss-diets (accessed on 1 June 2016).

- Donnelly, J.E.; Blair, S.N.; Jakicic, J.M.; Manore, M.M.; Rankin, J.W.; Smith, B.K. Appropriate physical activity intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2009, 41, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, J.; Truesdale, K.P.; McClain, J.E.; Cai, J. The definition of weight maintenance. Int. J. Obes. 2006, 30, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Green, S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 5.1.0; The Cochrane Collaboration: London, UK, 2007; Available online: http://handbook.cochrane.org/ (accessed on 11 July 2016).

- Dansinger, M.L.; Gleason, J.A.; Griffith, J.L.; Selker, H.P.; Schaefer, E.J. Comparison of the atkins, ornish, weight watchers, and zone diets for weight loss and heart disease risk reduction: A randomized trial. JAMA 2005, 293, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, G.D.; Wyatt, H.R.; Hill, J.O.; McGuckin, B.G.; Brill, C.; Mohammed, B.S.; Szapary, P.O.; Rader, D.J.; Edman, J.S.; Klein, S. A randomized trial of a low-carbohydrate diet for obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 2082–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, G.D.; Wyatt, H.R.; Hill, J.O.; Makris, A.P.; Rosenbaum, D.L.; Brill, C.; Stein, R.I.; Mohammed, B.S.; Miller, B.; Rader, D.J.; et al. Weight and metabolic outcomes after 2 years on a low-carbohydrate versus low-fat diet: A randomized trial. Ann. Int. Med. 2010, 153, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, C.D.; Kiazand, A.; Alhassan, S.; Kim, S.; Stafford, R.S.; Balise, R.R.; Kraemer, H.C.; King, A.C. Comparison of the Atkins, Zone, Ornish, and LEARN diets for change in weight and related risk factors among overweight premenopausal women: The A TO Z Weight Loss Study: A randomized trial. JAMA 2007, 297, 969–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAuley, K.A.; Hopkins, C.M.; Smith, K.J.; McLay, R.T.; Williams, S.M.; Taylor, R.W.; Mann, J.I. Comparison of high-fat and high-protein diets with a high-carbohydrate diet in insulin-resistant obese women. Diabetologia 2005, 48, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Summer, S.S.; Brehm, B.J.; Benoit, S.C.; D’Alessio, D.A. Adiponectin changes in relation to the macronutrient composition of a weight-loss diet. Obesity 2011, 19, 2198–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truby, H.; Baic, S.; de Looy, A.; Fox, K.R.; Livingstone, M.B.; Logan, C.M.; Macdonald, I.A.; Morgan, L.M.; Taylor, M.A.; Millward, D.J. Randomised controlled trial of four commercial weight loss programmes in the UK: Initial findings from the BBC “diet trials”. BMJ 2006, 332, 1309–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yancy, W.S., Jr.; Westman, E.C.; McDuffie, J.R.; Grambow, S.C.; Jeffreys, A.S.; Bolton, J.; Chalecki, A.; Oddone, E.Z. A randomized trial of a low-carbohydrate diet vs. orlistat plus a low-fat diet for weight loss. Arch. Int. Med. 2010, 170, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shai, I.; Schwarzfuchs, D.; Henkin, Y.; Shahar, D.R.; Witkow, S.; Greenberg, I.; Golan, R.; Fraser, D.; Bolotin, A.; Vardi, H.; et al. Weight loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, N.J.; Tomuta, N.; Schechter, C.; Isasi, C.R.; Segal-Isaacson, C.J.; Stein, D.; Zonszein, J.; Wylie-Rosett, J. Comparative study of the effects of a 1-year dietary intervention of a low-carbohydrate diet versus a low-fat diet on weight and glycemic control in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 1147–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blumenthal, J.A.; Babyak, M.A.; Sherwood, A.; Craighead, L.; Lin, P.H.; Johnson, J.; Watkins, L.L.; Wang, J.T.; Kuhn, C.; Feinglos, M.; et al. Effects of the dietary approaches to stop hypertension diet alone and in combination with exercise and caloric restriction on insulin sensitivity and lipids. Hypertension 2010, 55, 1199–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebbeling, C.B.; Leidig, M.M.; Feldman, H.A.; Lovesky, M.M.; Ludwig, D.S. Effects of a low-glycemic load vs low-fat diet in obese young adults: A randomized trial. JAMA 2007, 297, 2092–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melanson, K.J.; Summers, A.; Nguyen, V.; Brosnahan, J.; Lowndes, J.; Angelopoulos, T.J.; Rippe, J.M. Body composition, dietary composition, and components of metabolic syndrome in overweight and obese adults after a 12-week trial on dietary treatments focused on portion control, energy density, or glycemic index. Nutr. J. 2012, 11, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhayany, A.; Lustman, A.; Abel, R.; Attal-Singer, J.; Vinker, S. A low carbohydrate Mediterranean diet improves cardiovascular risk factors and diabetes control among overweight patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A 1-year prospective randomized intervention study. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2010, 12, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austel, A.; Ranke, C.; Wagner, N.; Gorge, J.; Ellrott, T. Weight loss with a modified Mediterranean-type diet using fat modification: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 69, 878–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee: Advisory Report to the Secretary of Health and Human Services and the Secretary of Agriculture; Department of Health and Human Services DoA: Madison, WI, USA, 2015. Available online: https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015-scientific-report/pdfs/scientific-report-of-the-2015-dietary-guidelines-advisory-committee.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2016).

- Chen, T.Y.; Smith, W.; Rosenstock, J.L.; Lessnau, K.D. A life-threatening complication of Atkins diet. Lancet 2006, 367, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expert Panel on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight in Adults. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: Executive summary. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998, 68, 899–917. [Google Scholar]

- Pi-Sunyer, F.X. A review of long-term studies evaluating the efficacy of weight loss in ameliorating disorders associated with obesity. Clin. Ther. 1996, 18, 1006–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, S.D.; Foreyt, J.; Perri, M.G. Preventing Weight Regain after Weight Loss. In Handbook of Obesity Treatment: Clinical Applications, 4th ed.; Informa Healthcare: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Scheen, A.J. The future of obesity: New drugs versus lifestyle interventions. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2008, 17, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noakes, T.D.; Windt, J. Evidence that supports the prescription of low-carbohydrate high-fat diets: A narrative review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2017, 51, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebbeling, C.B.; Swain, J.F.; Feldman, H.A.; Wong, W.W.; Hachey, D.L.; Garcia-Lago, E.; Ludwig, D.S. Effects of dietary composition on energy expenditure during weight-loss maintenance. JAMA 2012, 307, 2627–2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolland, Y.; Czerwinski, S.; van Abellan, K.G.; Morley, J.E.; Cesari, M.; Onder, G.; Woo, J.; Baumgartner, R.; Pillard, F.; Boirie, Y.; et al. Sarcopenia: Its assessment, etiology, pathogenesis, consequences and future perspectives. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2008, 12, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamboni, M.; Rossi, A.P.; Fantin, F.; Zamboni, G.; Chirumbolo, S.; Zoico, E.; Mazzali, G. Adipose tissue, diet and aging. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2014, 136–137, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Corral, A.; Somers, V.K.; Sierra-Johnson, J.; Korenfeld, Y.; Boarin, S.; Korinek, J.; Jensen, M.D.; Parati, G.; Lopez-Jimenez, F. Normal weight obesity: A risk factor for cardiometabolic dysregulation and cardiovascular mortality. Eur. Heart J. 2010, 31, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveros, E.; Somers, V.K.; Sochor, O.; Goel, K.; Lopez-Jimenez, F. The concept of normal weight obesity. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2014, 56, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques-Vidal, P.; Pecoud, A.; Hayoz, D.; Paccaud, F.; Mooser, V.; Waeber, G.; Vollenweider, P. Normal weight obesity: Relationship with lipids, glycaemic status, liver enzymes and inflammation. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2010, 20, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosmala, W.; Jedrzejuk, D.; Derzhko, R.; Przewlocka-Kosmala, M.; Mysiak, A.; Bednarek-Tupikowska, G. Left ventricular function impairment in patients with normal-weight obesity: Contribution of abdominal fat deposition, profibrotic state, reduced insulin sensitivity, and proinflammatory activation. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2012, 5, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batsis, J.A.; Sahakyan, K.R.; Rodriguez-Escudero, J.P.; Bartels, S.J.; Somers, V.K.; Lopez-Jimenez, F. Normal weight obesity and mortality in United States subjects ≥60 years of age (from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey). Am. J. Cardiol. 2013, 112, 1592–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Diet Name | Diet Type (Macronutrient Composition) | Calorie-Specific Recommendation | Exercise Component |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abs Diet | 6 meals/day, emphasis on protein | None | Required |

| Acid Alkaline Diet | 80% high pH (7–14) foods, 20% low pH (0–7) foods | None | Not Specified |

| Anti-Inflammatory Diet | Healthy fats d, complex carbs and limited animal protein | 2000–3000 kcal/day c | Encouraged |

| Atkins Diet [8] | During the first 2 weeks, less than 20 g of carbohydrate daily, with a gradual increase to 50 g daily | None | Encouraged |

| Biggest Loser Diet | Emphasis on complex carbs, lean proteins, few saturated fats and sugars | None | Required |

| Body Reset Diet a | Low-calorie, plant-based diet, mostly smoothies for 2 weeks | None | Required |

| DASH Diet b [3,9] | Emphasis on complex carbs, lean protein, low-fat dairy, fruits and vegetables | Monitored c | Encouraged |

| Dukan Diet | High-Protein, low-fat, low-carb | None | Required |

| Eco-Atkins Diet [10] | Low-Carb & exclusion of animal proteins | None | Not Specified |

| Engine 2 Diet | Vegan diet with no vegetable oils | None | Encouraged |

| Flat Belly Diet | Plant-based fats in every meal; complex carbs, lean protein and healthy fats d | 1600 kcal/day c | Encouraged |

| Flexitarian Diet | Mostly vegetarian, utilizing animal proteins sparingly | 1500 kcal/day | Encouraged |

| Glycemic-Index Diet [11] | Mostly low GI (≤55), some medium GI (56–69) and few high GI (≥70) foods | None | Not Specified |

| HMR Diet a | Meal Replacement | None | Encouraged |

| Jenny Craig Diet a | Meal Replacement | 1200–2300 kcal/day c | Required |

| Macrobiotic Diet | Emphasis on whole “living” foods: vegetarian and organic | None | Encouraged |

| Mayo Clinic Diet | Emphasis on complex carbs, low in saturated fat and salt | None | Required |

| Medifast Diet a | Meal Replacement | 800–1000 kcal/day | Encouraged |

| Mediterranean Diet [3] | Complex carbs and healthy fats d; few red meats, sugars and saturated fats | None | Required |

| MIND Diet | Emphasis on vegetables, nuts, berries, beans, whole grains, fish, poultry and olive oil (DASH + Mediterranean Diet) | None | Not Specified |

| Nutrisystem Diet a | Meal Replacement | None | Encouraged |

| Ornish Diet [12] | A vegetarian diet containing 10% of calories from fat | None | Encouraged |

| Paleolithic Diet [13] | Focus on meats, fruits and vegetables; cuts out refined sugar, diary and grains | None | Encouraged |

| Raw Food Die t a | 75–80% plant based foods; all food is never heated over 115 °F | None | Not Specified |

| Slim-Fast a | Meal Replacement | 1200 kcal/day | Encouraged |

| South Beach Diet | Low-carb, high-protein and healthy fats d | None | Required |

| Spark Solution Diet | Balanced (45–65% carbs, 20–35% fats and 16–35% proteins) | ≤1500 kcal/day | Required |

| Supercharged Hormone Diet | 2-week detox to identify and remove allergenic/inflammatory food | None | Required |

| The Fast Diet a | 5 days of normal meals, 2 non-consecutive days of fasting | M, 600 kcal/day; F, 500 kcal/day (2 day/week) | Not Specified |

| The Fertility Diet | Emphasis on plant proteins, whole grains | None | Encouraged |

| TLC Diet | Low-Fat; no more than 200 mg dietary cholesterol daily, red meat discouraged | M, 1600–2500 kcal/day; F, 1200–1600 kcal/day | Required |

| Traditional Asian Diet | Low-fat, emphasis on rice, vegetables, fresh fruit, fish; red meat sparingly | None | Not Specified |

| Vegan Diet [14] | Exclusion of all animal products and bi-products | None | Not Specified |

| Vegetarian Diet [3] | Exclusion of animal proteins | None | Not Specified |

| Volumetrics Diet | Emphasis on low calorie, high volume foods | None | Encouraged |

| Weight Watchers® | Point values based on macronutrient composition, personalized point cap/day | None | Encouraged |

| Whole30 Diet | Avoid sugar, alcohol, grains, dairy, and legumes for 30 days | None | Not Specified |

| Zone Diet b [15] | Balanced (40% carbs, 30% protein, and 30% fat) | M, 1500 kcal/day; F, 1200 kcal/day | Encouraged |

| Diet Reference | N | Age (Years) | Baseline BMI (kg/m2) | Short-Term | Long-Term | Macronutrients Protein:Fat:Carbohydrate (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period (Mo) | Weight Change | Period (Mo) | Weight Change | |||||||

| (kg) | (%) | (kg) | (%) | |||||||

| Atkins | ||||||||||

| Foster et al. [21] | 33 | 44 ± 9.4 | 33.9 ± 3.8 | 3 | −8.0 | −8.1 | 12 | −7.2 | −7.3 | |

| 6 | −9.6 | −9.7 | ||||||||

| Dansinger et al. [20] | 40 | 47 ± 12 | 35 ± 3.5 | 6 | −3.2 ± 4.9 | −3.5 | 12 | −2.1 ± 4.8 | −2.1 | 18:37:50 (Base) |

| 26:50:16 (1 Mo) | ||||||||||

| 18:39:41 (6 Mo) | ||||||||||

| 18:38:40 (12 Mo) | ||||||||||

| McAuley et al. [24] | 31 | 45 ± 7.4 | 36.0 ± 3.9 | 4 | −6.9 | −7.2 | No data | 18:34:44 (Base) | ||

| 29:57:11 (2 Mo) | ||||||||||

| 6 | −7.1 | −7.4 | 24:47:26 (6 Mo) | |||||||

| Truby et al. [26] | 57 | 40.9 ± 9.7 | 31.9 ± 2.2 | 6 | −6.0 ± 6.4 | −6.6 | 12 * | −9.0 ± 4.1 * | −10.0 | |

| Gardner et al. [23] | 77 | 42 ± 6 | 32 ± 4 | 6 | −5.8 | −6.7 | 12 | −4.7 | −5.5 | 17:36:46 (Base) |

| 28:55:18 (2 Mo) | ||||||||||

| 22:47:30 (6 Mo) | ||||||||||

| 21:44:35 (12 Mo) | ||||||||||

| Shai et al. [28] | 109 | 52 ± 7 | 30.8 ± 3.5 | 6 | −6.3 | −6.9 | 12 | −5.2 | −5.7 | 19:31:51 (Base) |

| 22:39:41 (6 Mo) | ||||||||||

| 24 | −4.7 | −5.1 | 22:39:42 (12 Mo) | |||||||

| 22:39:40 (24 Mo) | ||||||||||

| Davis et al. [29] | 55 | 54 ± 6 | 35 ± 6 | 3 | −5.2 | −5.6 | 12 | −3.1 | −3.3 | 20:36:44 (Base) |

| 23:43:34 (6 Mo) | ||||||||||

| 6 | −4.8 | −5.1 | 23:44:33 (12 Mo) | |||||||

| Foster et al. [22] | 153 | 46.2 ± 9.2 | 36.1 ± 3.6 | 6 | −12.2 | −11.8 | 12 | −10.9 | −10.5 | |

| 24 | −6.3 | −6.1 | ||||||||

| Yancy et al. [27] | 72 | 52.9 ± 10.2 | 39.9 ± 6.9 | 3 | −9.7 | −7.9 | 12 | −11.4 | −9.2 | 16:40:44 (Base) |

| 30:59:10 (2 w) | ||||||||||

| 29:57:12 (3 Mo) | ||||||||||

| 6 | −12.8 | −10.4 | 28:57:13 (6 Mo) | |||||||

| 26:57:15 (12 Mo) | ||||||||||

| Summer et al. [25] † | 42 | 44.5 ± 9.2 | 33.2 ± 2.6 | 4/6 | −9.1 | −10.1 | No data | 16:36:48 (Base) | ||

| 24:49:27 (Post-intervention) | ||||||||||

| DASH | ||||||||||

| Blumenthal et al. [30] | 46 | 51.8 ± 10 | 32.8 ± 3.4 | 4 | −0.3 | −0.3 | No data | |||

| Glycemic Index | ||||||||||

| Ebbling et al. [31] | 36 | 28.2 ± 3.8 | >30 | 6 | −4.5 | −4.4 | 12 | −3.0 | −2.9 | Emphasis to 25:35:40 from low–glycemic index sources |

| Melanson et al. [32] | 59 | 39.1 ± 7.1 | 31.1 ± 2.5 | 3 | −3.4 ± 2.8 | −4.0 | No data | 17:36:47 (Base) | ||

| 22:33:47 (3 Mo) | ||||||||||

| Mediterranean | ||||||||||

| Elhayany et al. [33] | 89 | 56.0 ± 6.1 | 27–34 | No data | 12 | −7.4 | −8.7 | Recommend to 20:30:50 | ||

| Auster et al. [34] | 100 | 52.4 ± 0.9 | 30.1 ± 0.3 | 3 | −6.1 | −7.2 | No data | |||

| Ornish | ||||||||||

| Dansinger et al. [20] | 40 | 49 ± 12 | 35 ± 3.9 | 6 | −3.6 ± 6.7 | −3.5 | 12 | −3.3 ± 7.3 | −3.2 | 18:35:49 (Base) |

| 17:29:55 (6 Mo) | ||||||||||

| 17:32:48 (12 Mo) | ||||||||||

| Gardner et al. [23] | 76 | 42 ± 6 | 32 ± 3 | 6 | −2.5 | −2.9 | 12 | −2.2 | −2.6 | 16:35:48 (Base) |

| 18:28:53 (6 Mo) | ||||||||||

| 18:30:52 (12 Mo) | ||||||||||

| Paleolithic | ||||||||||

| Mellberg et al. [13] | 35 | 59.5 ± 5.5 | 32.7 ± 3.6 | 6 | −7.85 | −9.0 | 24 | −9.2 | −10.6 | 17:33:46 (Base) |

| 23:44:29 (6 Mo) | ||||||||||

| 22:40:34 (24 Mo) | ||||||||||

| Zone | ||||||||||

| Dansinger et al. [20] | 40 | 51 ± 9 | 34 ± 4.5 | 6 | −3.4 ± 5.7 | −3.4 | 12 | −3.2 ± 6.0 | −3.2 | 18:35:46 (Base) |

| 19:32:42 (6 Mo) | ||||||||||

| 21:37:39 (12 Mo) | ||||||||||

| McAuley et al. [24] | 30 | 30–70 | 34.5 ± 5.3 | 6 | −6.9 | −7.4 | 17:31:47 (Base) | |||

| 26:35:35 (6 Mo) | ||||||||||

| Gardner et al. [23] | 79 | 40 ± 6 | 31 ± 3 | 6 | −2.0 | −2.4 | 12 | −1.5 | −1.8 | 17:37:47 (Base) |

| 20:36:44 (6 Mo) | ||||||||||

| 20:35:45 (12 Mo) | ||||||||||

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anton, S.D.; Hida, A.; Heekin, K.; Sowalsky, K.; Karabetian, C.; Mutchie, H.; Leeuwenburgh, C.; Manini, T.M.; Barnett, T.E. Effects of Popular Diets without Specific Calorie Targets on Weight Loss Outcomes: Systematic Review of Findings from Clinical Trials. Nutrients 2017, 9, 822. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9080822

Anton SD, Hida A, Heekin K, Sowalsky K, Karabetian C, Mutchie H, Leeuwenburgh C, Manini TM, Barnett TE. Effects of Popular Diets without Specific Calorie Targets on Weight Loss Outcomes: Systematic Review of Findings from Clinical Trials. Nutrients. 2017; 9(8):822. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9080822

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnton, Stephen D., Azumi Hida, Kacey Heekin, Kristen Sowalsky, Christy Karabetian, Heather Mutchie, Christiaan Leeuwenburgh, Todd M. Manini, and Tracey E. Barnett. 2017. "Effects of Popular Diets without Specific Calorie Targets on Weight Loss Outcomes: Systematic Review of Findings from Clinical Trials" Nutrients 9, no. 8: 822. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9080822

APA StyleAnton, S. D., Hida, A., Heekin, K., Sowalsky, K., Karabetian, C., Mutchie, H., Leeuwenburgh, C., Manini, T. M., & Barnett, T. E. (2017). Effects of Popular Diets without Specific Calorie Targets on Weight Loss Outcomes: Systematic Review of Findings from Clinical Trials. Nutrients, 9(8), 822. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9080822