Vitamin D Status and Efficacy of Vitamin D Supplementation in Atopic Dermatitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

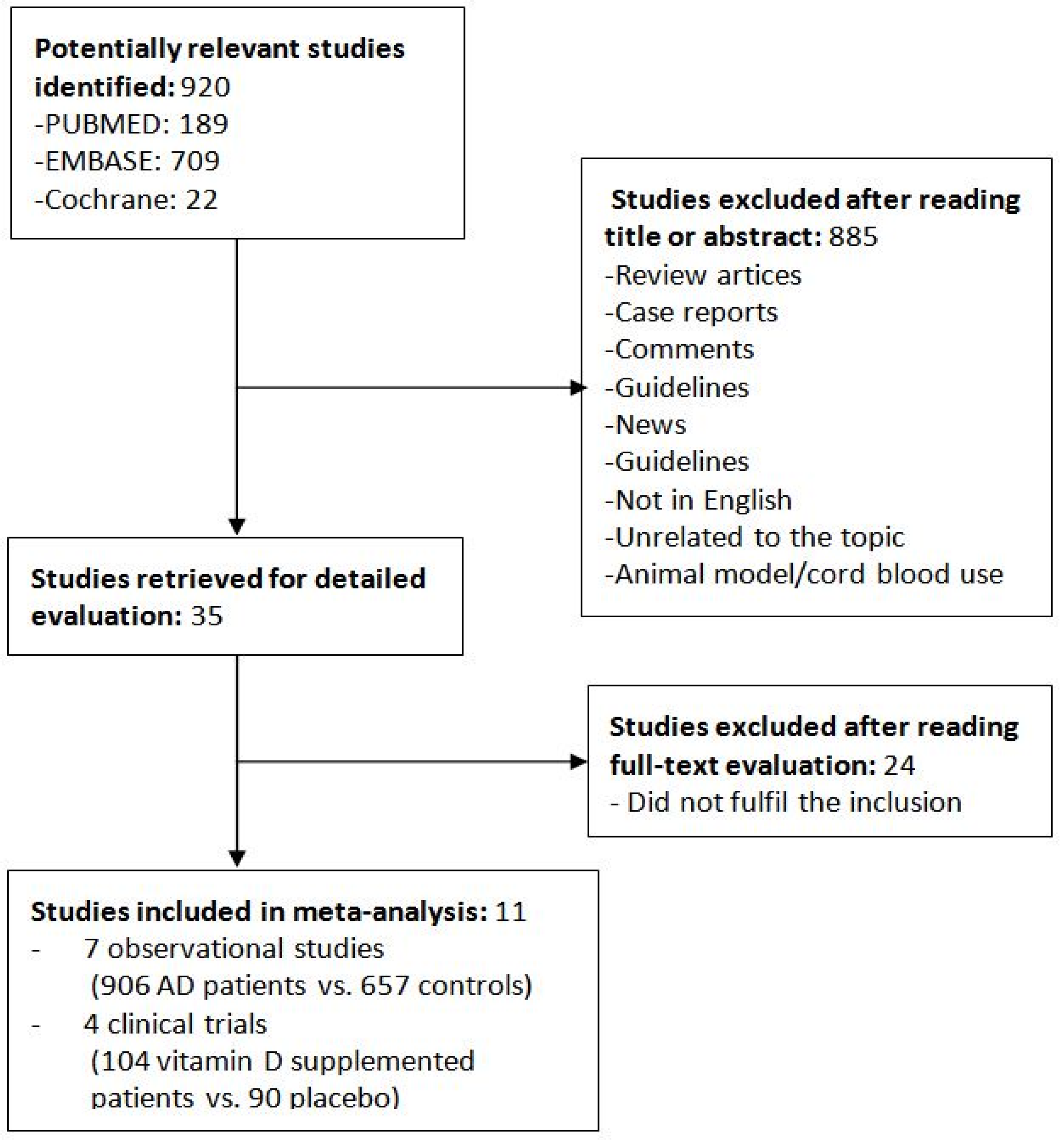

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Data Collection

2.2. Study Selection and Data Extraction

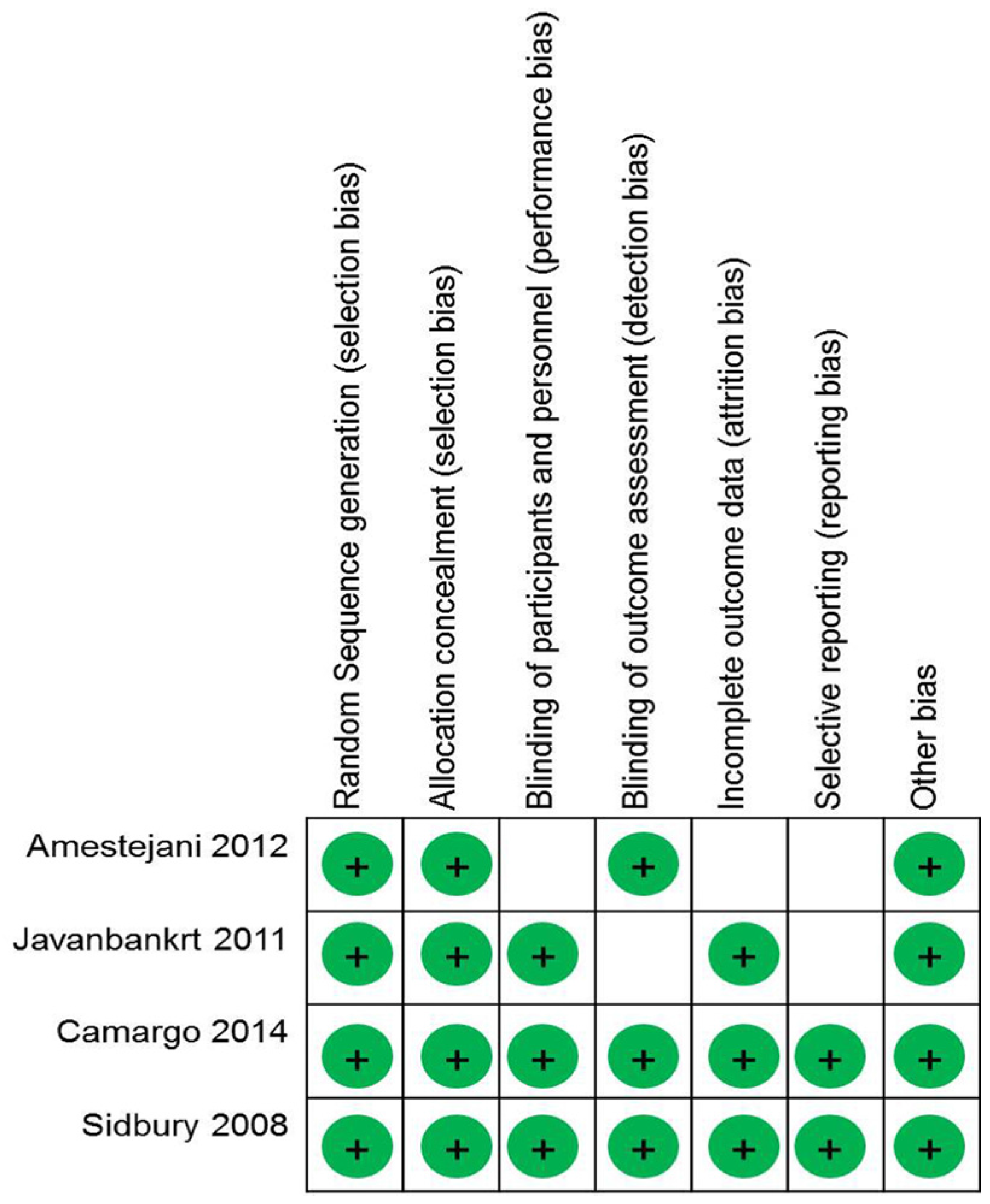

2.3. Quality of Assessment

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

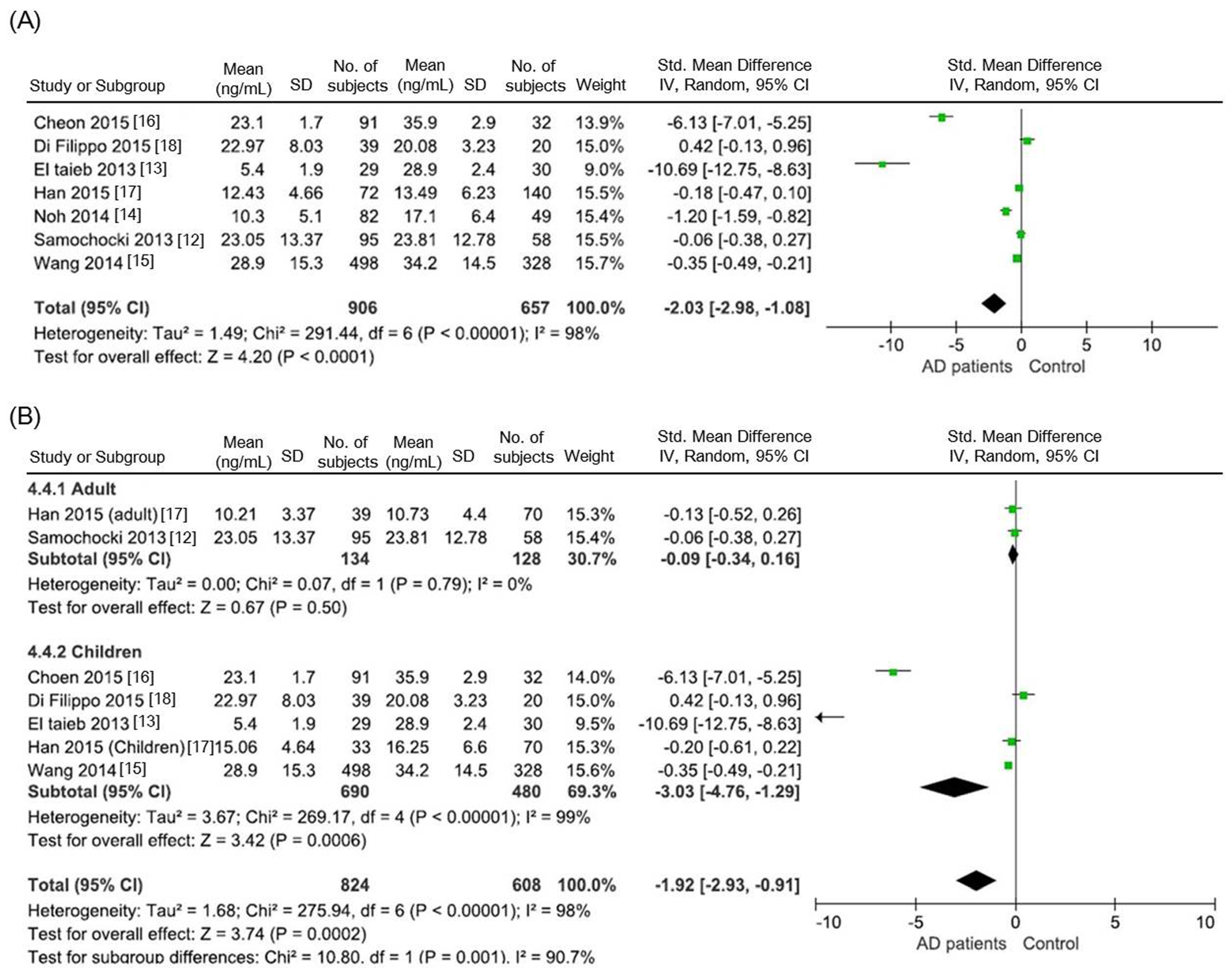

3.1. Comparison of Serum 25(OH)D Levels between AD Patients and Healthy Controls

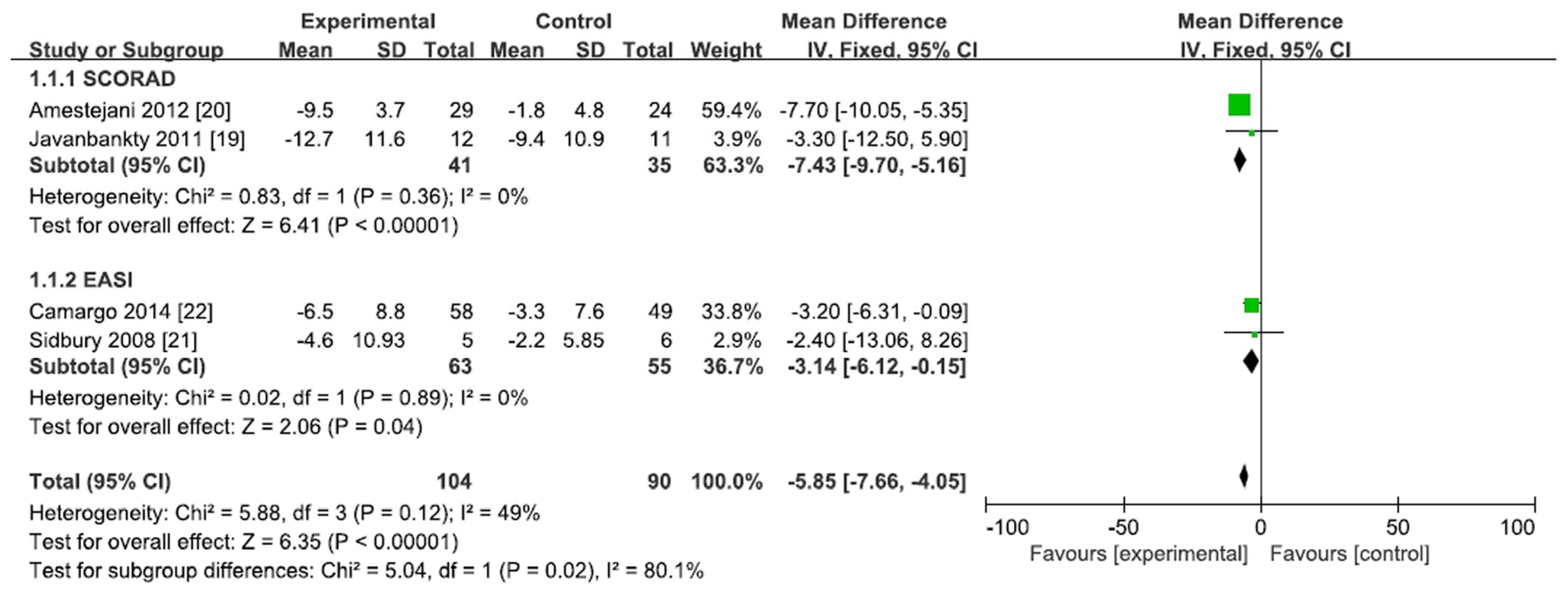

3.2. Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation in AD Patients

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bieber, T. Atopic dermatitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 1483–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, H.; Robertson, C.; Stewart, A.; Ait-Khaled, N.; Anabwani, G.; Anderson, R.; Asher, I.; Beasley, R.; Bjorksten, B.; Burr, M.; et al. Worldwide variations in the prevalence of symptoms of atopic eczema in the international study of asthma and allergies in childhood. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1999, 103, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, D.Y.; Bieber, T. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet 2003, 361, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichenfield, L.F.; Tom, W.L.; Berger, T.G.; Krol, A.; Paller, A.S.; Schwarzenberger, K.; Bergman, J.N.; Chamlin, S.L.; Cohen, D.E.; Cooper, K.D.; et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: Section 2. Management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2014, 71, 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bath-Hextall, F.J.; Jenkinson, C.; Humphreys, R.; Williams, H.C. Dietary supplements for established atopic eczema. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 2, CD005205. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The prisma statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, G.; Shea, B.; O’Connel, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses; Department of Epidemiology and Community Medicine, University of Ottawa: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Review of Interventions. 2011. Available online: www.handbook.cochrane.org (accessed on 1 July 2015).

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egger, M.; Smith, G.; Altman, D.G. Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-Analysis in Context, 2nd ed.; BMJ Publishing Group: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne, J.A.; Egger, M. Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: Guidelines on choice of axis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2001, 54, 1046–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samochocki, Z.; Bogaczewicz, J.; Jeziorkowska, R.; Sysa-Jedrzejowska, A.; Glinska, O.; Karczmarewicz, E.; McCauliffe, D.P.; Wozniacka, A. Vitamin D effects in atopic dermatitis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2013, 69, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Taieb, M.A.; Fayed, H.M.; Aly, S.S.; Ibrahim, A.K. Assessment of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels in children with atopic dermatitis: Correlation with scorad index. Dermatitis 2013, 24, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noh, S.; Park, C.O.; Bae, J.M.; Lee, J.; Shin, J.U.; Hong, C.S.; Lee, K.H. Lower vitamin D status is closely correlated with eczema of the head and neck. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 133, 1767.e6–1770.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.S.; Hon, K.L.; Kong, A.P.; Pong, H.N.; Wong, G.W.; Leung, T.F. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with diagnosis and severity of childhood atopic dermatitis. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2014, 25, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheon, B.R.; Shin, J.E.; Kim, Y.J.; Shim, J.W.; Kim, D.S.; Jung, H.L.; Park, M.S.; Shim, J.Y. Relationship between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and interleukin-31 levels, and the severity of atopic dermatitis in children. Korean J. Pediatr. 2015, 58, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, T.Y.; Kong, T.S.; Kim, M.H.; Chae, J.D.; Lee, J.H.; Son, S.J. Vitamin D status and its association with the scorad score and serum LL-37 level in korean adults and children with atopic dermatitis. Ann. Dermatol. 2015, 27, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Filippo, P.; Scaparrotta, A.; Rapino, D.; Cingolani, A.; Attanasi, M.; Petrosino, M.I.; Chuang, K.; Di Pillo, S.; Chiarelli, F. Vitamin D supplementation modulates the immune system and improves atopic dermatitis in children. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2015, 166, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javanbakht, M.H.; Keshavarz, S.A.; Djalali, M.; Siassi, F.; Eshraghian, M.R.; Firooz, A.; Seirafi, H.; Ehsani, A.H.; Chamari, M.; Mirshafiey, A. Randomized controlled trial using vitamins E and D supplementation in atopic dermatitis. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2011, 22, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amestejani, M.; Salehi, B.S.; Vasigh, M.; Sobhkhiz, A.; Karami, M.; Alinia, H.; Kamrava, S.K.; Shamspour, N.; Ghalehbaghi, B.; Behzadi, A.H. Vitamin D supplementation in the treatment of atopic dermatitis: A clinical trial study. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2012, 11, 327–330. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sidbury, R.; Sullivan, A.F.; Thadhani, R.I.; Camargo, C.A., Jr. Randomized controlled trial of vitamin D supplementation for winter-related atopic dermatitis in Boston: A pilot study. Br. J. Dermatol. 2008, 159, 245–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camargo, C.A., Jr.; Ganmaa, D.; Sidbury, R.; Erdenedelger, K.; Radnaakhand, N.; Khandsuren, B. Randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation for winter-related atopic dermatitis in children. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 134, 831.e1–835.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elias, P.M.; Hatano, Y.; Williams, M.L. Basis for the barrier abnormality in atopic dermatitis: Outside-inside-outside pathogenic mechanisms. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2008, 121, 1337–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Searing, D.A.; Leung, D.Y. Vitamin D in atopic dermatitis, asthma and allergic diseases. Immunol. Allergy Clin. N. Am. 2010, 30, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.T.; Nestel, F.P.; Bourdeau, V.; Nagai, Y.; Wang, Q.; Liao, J.; Tavera-Mendoza, L.; Lin, R.; Hanrahan, J.W.; Mader, S.; et al. Cutting edge: 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 is a direct inducer of antimicrobial peptide gene expression. J. Immunol. 2004, 173, 2909–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.T.; Stenger, S.; Li, H.; Wenzel, L.; Tan, B.H.; Krutzik, S.R.; Ochoa, M.T.; Schauber, J.; Wu, K.; Meinken, C.; et al. Toll-like receptor triggering of a vitamin D-mediated human antimicrobial response. Science 2006, 311, 1770–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, D.Y.; Boguniewicz, M.; Howell, M.D.; Nomura, I.; Hamid, Q.A. New insights into atopic dermatitis. J. Clin. Investig. 2004, 113, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.M.; Kim, S.; Park, G.H.; Chang, S.E.; Bang, S.; Won, C.H.; Lee, M.W.; Choi, J.H.; Moon, K.C. Low vitamin D levels are associated with atopic dermatitis, but not allergic rhinitis, asthma, or ige sensitization, in the adult Korean population. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 133, 1048–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thuesen, B.H.; Heede, N.G.; Tang, L.; Skaaby, T.; Thyssen, J.P.; Friedrich, N.; Linneberg, A. No association between vitamin D and atopy, asthma, lung function or atopic dermatitis: A prospective study in adults. Allergy 2015, 70, 1501–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norizoe, C.; Akiyama, N.; Segawa, T.; Tachimoto, H.; Mezawa, H.; Ida, H.; Urashima, M. Increased food allergy and vitamin D: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatr. Int. 2014, 56, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Back, O.; Blomquist, H.K.; Hernell, O.; Stenberg, B. Does vitamin D intake during infancy promote the development of atopic allergy? Acta Derm. Venereol. 2009, 89, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, J.M.; Oh, S.H.; Shin, M.Y. The relationships among birth season, sunlight exposure during infancy, and allergic disease. Korean J. Pediatr. 2016, 59, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, T.H.; Clark, S.M.; Turner, D.; Goulden, V. The treatment of severe atopic dermatitis in childhood with narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2007, 32, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walters, I.B.; Ozawa, M.; Cardinale, I.; Gilleaudeau, P.; Trepicchio, W.L.; Bliss, J.; Krueger, J.G. Narrowband (312-nm) UV-B suppresses interferon gamma and interleukin (IL) 12 and increases IL-4 transcripts: Differential regulation of cytokines at the single-cell level. Arch. Dermatol. 2003, 139, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heaney, R.P. Guidelines for optimizing design and analysis of clinical studies of nutrient effects. Nutr. Rev. 2014, 72, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, C.; Yang, J.; Yu, W.; Li, D.; Xiang, Z.; Lin, Y.; Yu, C. Association between 25(OH)D level, ultraviolet exposure, geographical location, and inflammatory bowel disease activity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Year | Criterion Scores | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selection | Comparability | Exposure | ||

| Samochocki et al. [12] | 2013 | ★★★★ | ★★ | ★ |

| El Taieb et al. [13] | 2013 | ★★★★ | ★★ | ★ |

| Noh et al. [14] | 2014 | ★★★★ | ★★ | ★ |

| Wang et al. [15] | 2014 | ★★★ | ★★ | ★ |

| Cheon et al. [16] | 2015 | ★★★ | ★ | |

| Han et al. [17] | 2015 | ★★ | ★★ | ★ |

| Di Filippo et al. [18] | 2015 | ★★★ | ★★ | ★ |

| Study | Year | Study Population | Study Size | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samochocki et al. [12] | 2013 | Adults aged 18–50 years (mean age: 29.9 years) | 95 cases, 58 control subjects | Poland |

| El Taieb et al. [13] | 2013 | Children aged 2–12 years (mean age, AD group: 6.2 years, control group: 6.5 years) | 29 cases, 30 control subjects | Egypt |

| Noh et al. [14] | 2014 | All ages (mean age, AD group: 20.8 years, control group: 29.5 years) | 82 cases, 49 control subjects | Korea |

| Wang et al. [15] | 2014 | Children (mean age: 15.5 years, control group: 12.3 years) | 498 cases, 328 control subjects | Hong Kong |

| Cheon et al. [16] | 2015 | Children (median age, AD group: 6 years, control group: 6 years) | 91 cases, 32 control subjects | Korea |

| Han et al. [17] | 2015 | All ages (adult group aged 18–51 years, pediatric group aged 12 months–16 years) | 72 cases, 140 control subjects | Korea |

| Di Filippo et al. [18] | 2015 | Children (mean age, AD and control groups: 4 years) | 39 cases, 20 control subjects | Italy |

| Study | Year | Study Design | Study Population | Study Size | Dose and Frequency | Supplemented Vitamin D | Duration | Location | AD Severity Assessment | Changes in Severity Index (Experimental, Control) | SCORAD or EASI Index (Experimental (before→after), Control (before→after)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Javanbakht et al. [19] | 2011 | Randomized double-blind placebo controlled | All aged, 13–45 years | 12 cases, 11 placebo | 1600 IU, daily | Cholecalciferol (Vitamin D3) | 60 days | Iran, Tehran | SCORAD * | −12.7 ± 11.6, −9.4 ± 10.9 | 36.0 ± 3.7→23.3 ± 2.8, 31.7 ± 3.5→22.3 ± 3.0 |

| Amestejani et al. [20] | 2012 | Randomized double-blind placebo controlled | >14 years | 29 cases, 24 placebo | 1600 IU, NR | Cholecalciferol (Vitamin D3) | 2 months | Iran | SCORAD | −9.5 ± 3.7, −1.8 ± 4.8 | 24.8 ± 4.1→15.3 ± 3.1, 25.3 ± 5.2→23.46 ± 4.2 |

| Sidbury et al. [21] | 2008 | Randomized double-blind placebo controlled | Children, median: 7 years | 5 cases, 6 placebo | 1000 IU, NR | Ergocalciferol (Vitamin D2) | 1 month | USA | EASI * | −4.6 ± NR, −2.2 ± NR | NR * |

| Camargo et al. [22] | 2014 | Randomized double-blind placebo controlled | Children, mean: 9 years | 58 cases, 49 placebo | 1000 IU, daily | Cholecalciferol (Vitamin D3) | 1 month | Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia | EASI | −6.5 ± 8.8, −3.3 ± 7.6 | NR |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, M.J.; Kim, S.-N.; Lee, Y.W.; Choe, Y.B.; Ahn, K.J. Vitamin D Status and Efficacy of Vitamin D Supplementation in Atopic Dermatitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2016, 8, 789. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8120789

Kim MJ, Kim S-N, Lee YW, Choe YB, Ahn KJ. Vitamin D Status and Efficacy of Vitamin D Supplementation in Atopic Dermatitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2016; 8(12):789. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8120789

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Min Jung, Soo-Nyung Kim, Yang Won Lee, Yong Beom Choe, and Kyu Joong Ahn. 2016. "Vitamin D Status and Efficacy of Vitamin D Supplementation in Atopic Dermatitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Nutrients 8, no. 12: 789. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8120789

APA StyleKim, M. J., Kim, S.-N., Lee, Y. W., Choe, Y. B., & Ahn, K. J. (2016). Vitamin D Status and Efficacy of Vitamin D Supplementation in Atopic Dermatitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 8(12), 789. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8120789