Effect of Glycemic Index of Breakfast on Energy Intake at Subsequent Meal among Healthy People: A Meta-Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Search

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Collection Process and Items

2.5. Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

2.6. Synthesis of Results

3. Results

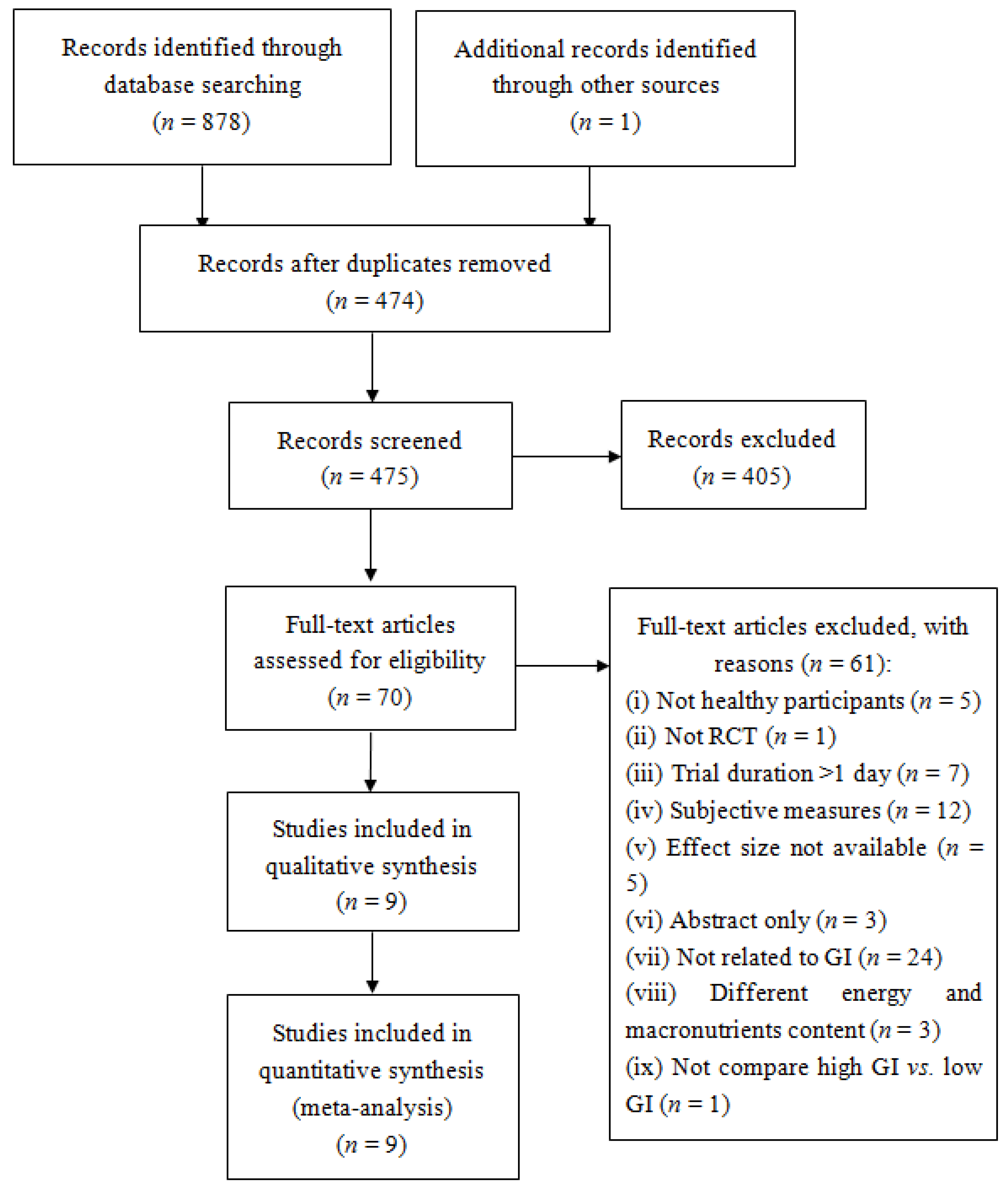

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Risk of Bias within Studies

| First Author and Year | Participants | Design | Criteria for GI Level (Duration) | Test Meal | Subsequent Food Intake | Key Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-GI | High-GI | ||||||

| Anderson (2002) [28], Trial 2 | n = 18 Age: 20–30 Gender: 18 M | RCT | AUC (60 min) | Amylose (75 g aCHO, 0 g protein, 0 g fat, 0 g fiber, 300 kcal) beverage | Amylopectin (75 g aCHO, 0 g protein, 0 g fat, 0 g fiber, 300 kcal); Sucrose (75 g aCHO, 0 g protein, 0 g fat, 0 g fiber, 300 kcal); Polycose (75 g aCHO, 0 g protein, 0 g fat, 0 g fiber, 300 kcal) beverage | Pizza meal according to one’s preference served at 60 min | Polycose resulted in significantly less food intake than did amylopectin |

| Anderson (2002) [28], Trial 3 | n = 18 Age: 18–35 Gender: 18 M | RCT | AUC (60 min) | Fructose-glucose (75 g aCHO, 0 g protein, 0 g fat, 0 g fiber, 300 kcal) beverage | Sucrose (75 g aCHO, 0 g protein, 0 g fat, 0 g fiber, 300 kcal); Polycose (75 g aCHO, 0 g protein, 0 g fat, 0 g fiber, 300 kcal); Glucose (75 g aCHO, 0 g protein, 0 g fat, 0 g fiber, 300 kcal) beverage | Pizza meal according to one’s preference served at 60 min | No difference |

| Anderson (2010) [29], Trial 1 | n = 17 Age: 20–30 Gender: 17 M | RCT | AUC (30 min) | Regular cornstarch with tomato soup (a high-amylopectin granular starch, 46.5 g aCHO, 1 g protein, 0 g fat, <1.5 g fiber, 190 kcal) | Malto-dextrin with tomato soup (a highly processed, non-granular starch, 47 g aCHO, 1 g protein, 0 g fat, 1 g fiber, 192 kcal) | Pizza meal according to one’s preference served at 30 min | No difference |

| Anderson (2010) [29], Trial 2 | n = 16 Age: 20–30 Gender: 16 M | RCT | AUC (120 min) | Regular cornstarch with tomato soup (46.5 g aCHO, 1 g protein, 0 g fat, <1.5 g fiber, 190 kcal) | Malto-dextrin with tomato soup (47 aCHO, 1 g protein, 0 g fat, 1 g fiber, 192 kcal) | Pizza meal according to one’s preference served at 120 min | No difference |

| Flint (2006) [30] | n = 28 Age: 24.8 (0.5) Gender: 28 M | RCT | iAUC (180 min) | Reference bread (50 g aCHO, 12 g protein, 7 g fat, 5 g fiber, 319 kcal); Frosties + milk (50 g aCHO, 9 g protein, 3 g fat, 1 g fiber, 270 kcal) | Porridge + rolled oats + water + applesauce (50 g aCHO, 8 g protein, 5 g fat, 6 g fiber, 289 kcal) | A pasta salad served at 180 min | No difference |

| Furchner-Evanson (2010) [31] | n = 21 Age: 20–30 Gender: 21 F | RCT | AUC (120 min) | Dried plums (48 g aCHO, 3 g protein, 0 g fat, 6 g fiber, 238 kcal) | Low-fat cookies (54 g aCHO, 4 g protein, 0 g fat, 0 g fiber, 238 kcal); White bread (42 g aCHO, 6 g protein, 3 g fat, 3 g fiber, 238 kcal) | A meal (strawberry flavored low-fat yogurt and granola) served at 120 min | No difference |

| Holt (1995) [33] | n = 9 Age: 19.3–29.0 Gender: 4 M, 5 F | RCT | AUC (120 min) | Ordinary boilded rice (50 g aCHO, 4.2 g protein, 0.4 g fat, 1.5 g fiber, 218 kcal); High amylose puffed rice cakes (50 g aCHO, 6.3 g protein, 2.1 g fat, fiber 2.7 g, 235 kcal) | Quick-cooking rice (50 g aCHO, 5.4 g protein, 0.6 g fat, 1.1 g fiber, 214 kcal); Low amylose puffed rice cakes (50 g aCHO, 4.8 g protein, 2.0 g fat, 2.6 g fiber, 228 kcal) | Eat freely from a limited range of food items served at 120 min | No difference |

| Kaplan (2002) [34] | n = 20 Age: 60–82 Gender: 10 M, 10 F | RCT | AUC (105 min) + GI value (white bread as the reference) | Pearled barley (46.6 aCHO, 5.9 g protein, 2.7 g fat, 9.4 g fiber, GI = 36, 228 kcal) | Instant mashed potato (49.5 g aCHO, 5.1 g protein, 2.2 g fat, 3.1 g fiber, GI = 118, 233 kcal) | Lunch (sandwiches, muffins, cookies) served at 120 min | No difference |

| Kristensen (2010) [35] | n = 16 Age: 24.1 (3.8) Gender: 6 M, 10 F | RCT | GI value (white bread as the reference) | Refined wheat pasta (50 g aCHO, 24 g protein, 17 g fat, 2.2 g fiber, 454 kcal, GI = 38) | Refined wheat bread (50 g aCHO, 23 g protein, 17 g fat, 3.6 g fiber, 444 kcal, GI = 100) | Pizza meal served at 180 min | No difference |

| Lumaga (2012) [36] | n = 14 Age: 24–39 Gender: 8 M, 6 F | RCT | AUC (180 min) | Control beverage (37.3 g aCHO, 0 g Protein, 0 g fat, 0 g fiber, 149 kcal) | Fruit-based beverage (34.3 g aCHO, 1.0 g protein, 0.3 g fat, 2.5 g fiber, 149 kcal) | Compose lunch tray based on one’s own desire to eat served at 180 min | No difference |

| Rodin (1991) [37] | n = 6 Age: 35.6 (2.4) Gender: 3 M, 3 F | RCT | AUC value (135 min) | Pudding sweetened with fructose (50 g aCHO, 24% protein, 41% fat, 530 kcal) | Pudding sweetened with glucose (50 g aCHO, 24% protein, 41% fat, 520 kcal) | Buffet lunch served at 135 min | Lower energy intake after low-GI food intake |

| First Author and Year | Randomization | Double Blinding | Withdrawals | Appropriate Randomization | Appropriate Double Blinding | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson (2002) [28], Trial 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Anderson (2002) 28], Trial 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Anderson (2010) [29], Trial 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Anderson (2010) [29], Trial 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Flint (2006) [30] | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Furchner-Evanson (2010) [31] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Holt (1995) [33] | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Kaplan (2002) [34] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Kristensen (2010) [35] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Lumaga (2012) [36] | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Rodin (1991) [37] | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

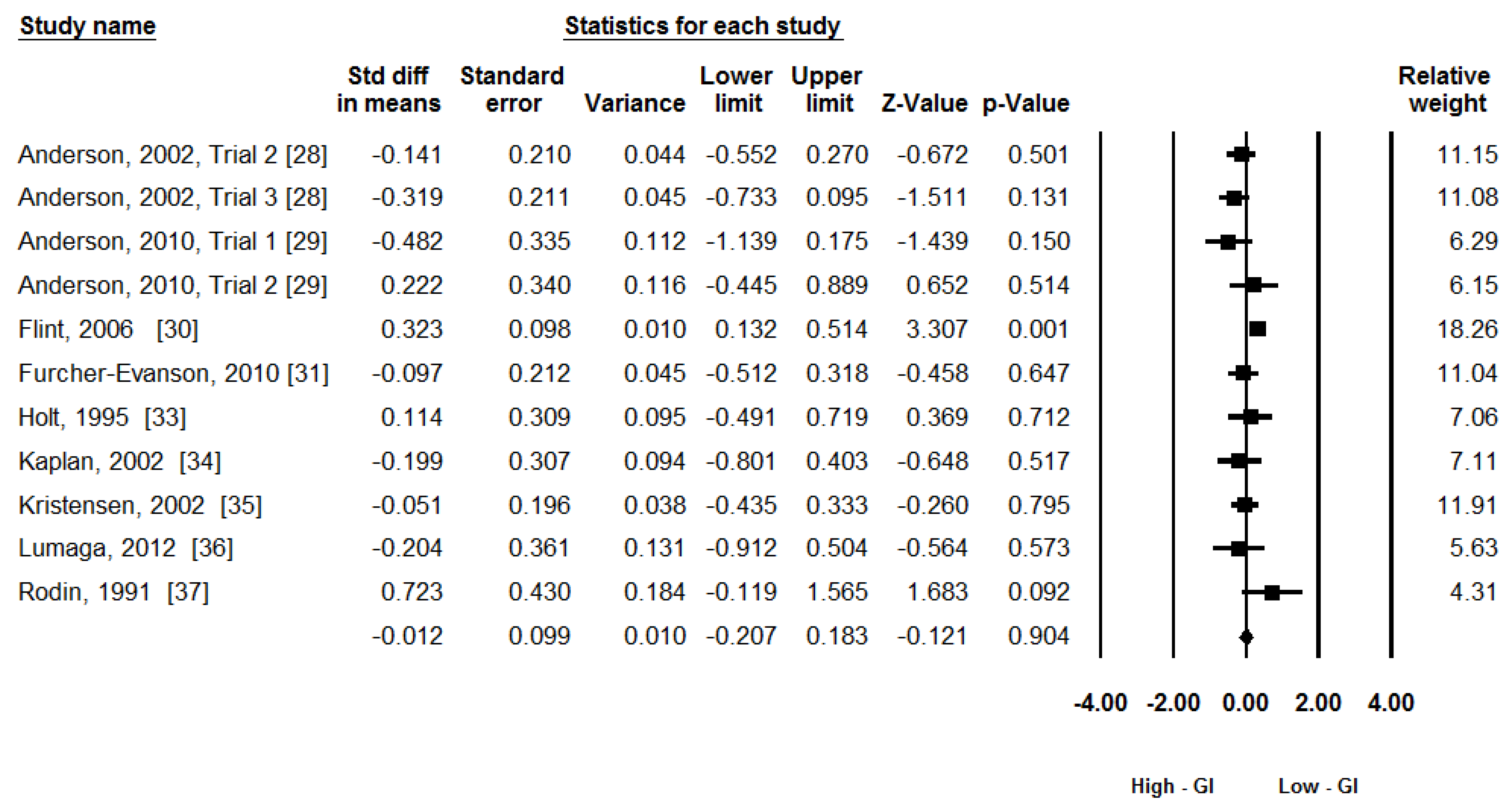

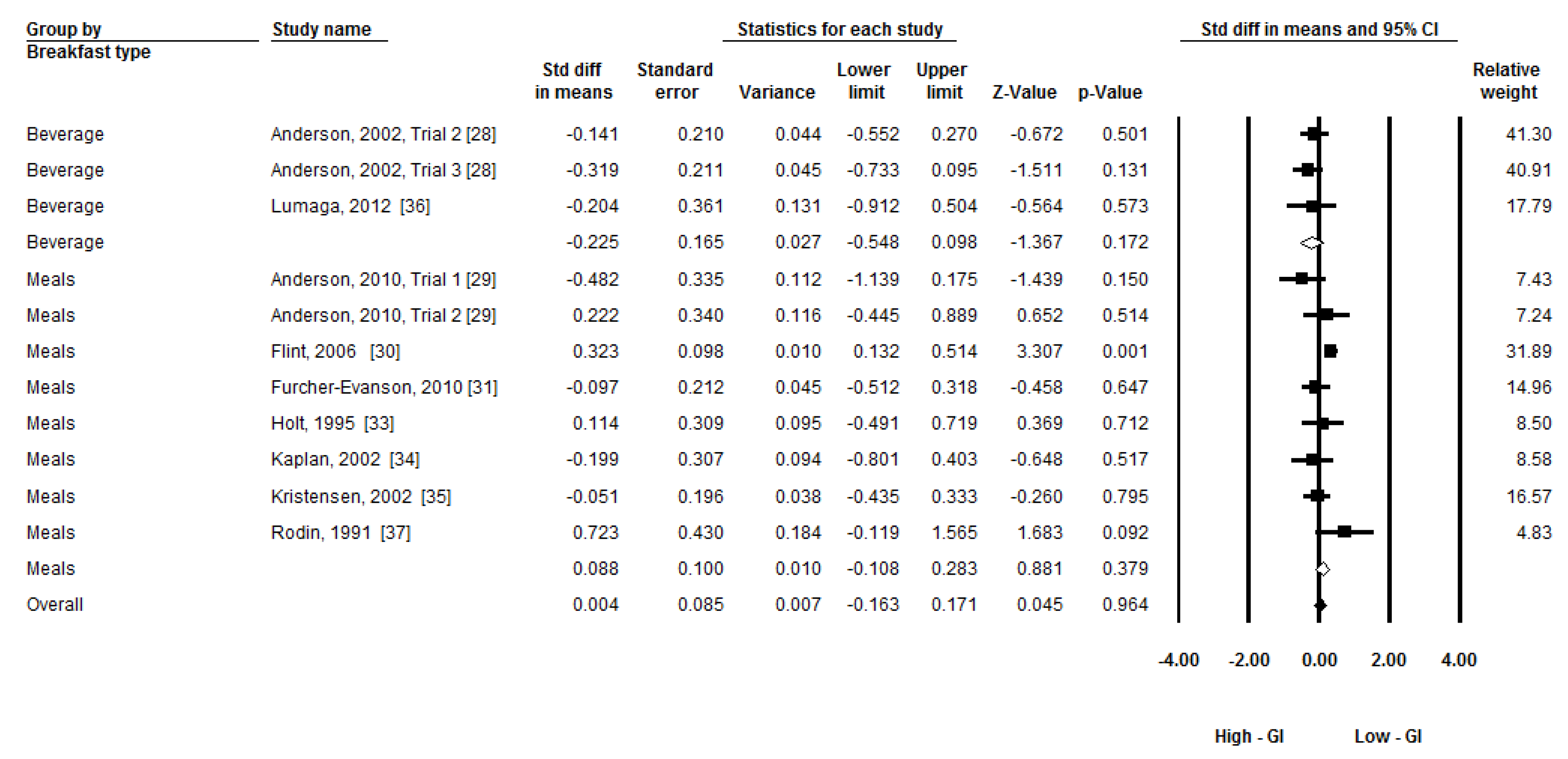

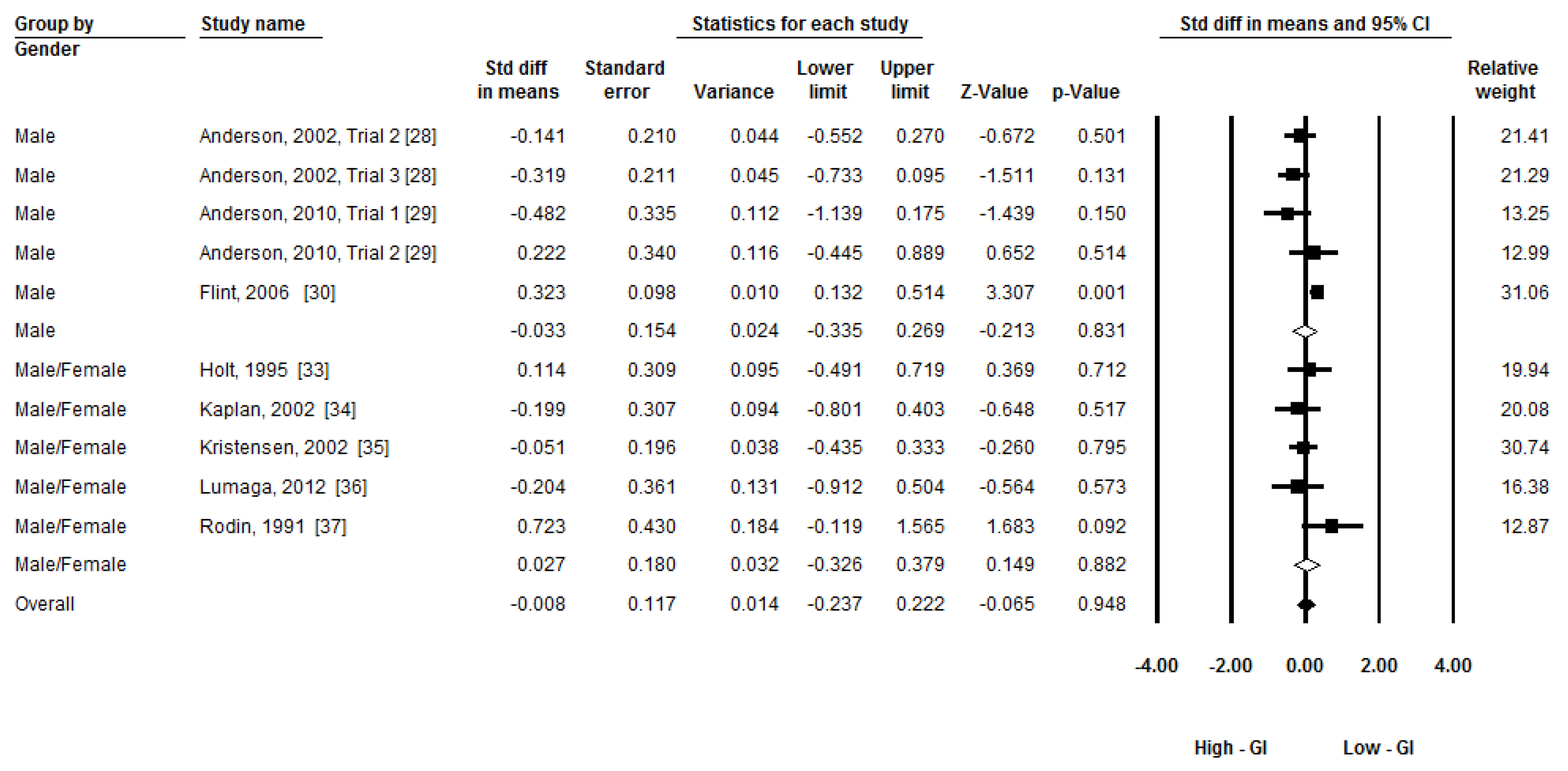

3.4. Synthesis of Results

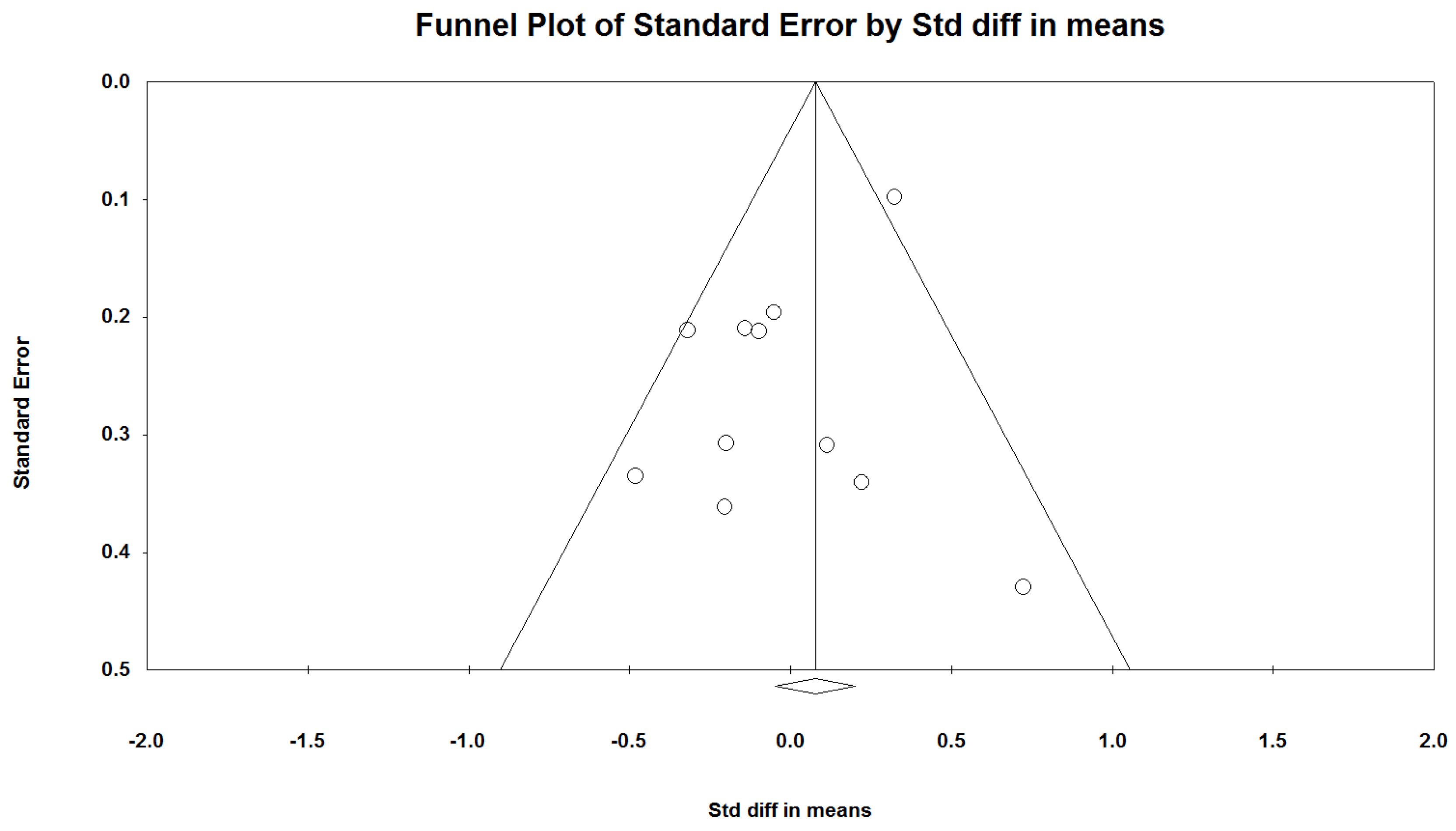

3.5. Publication Bias

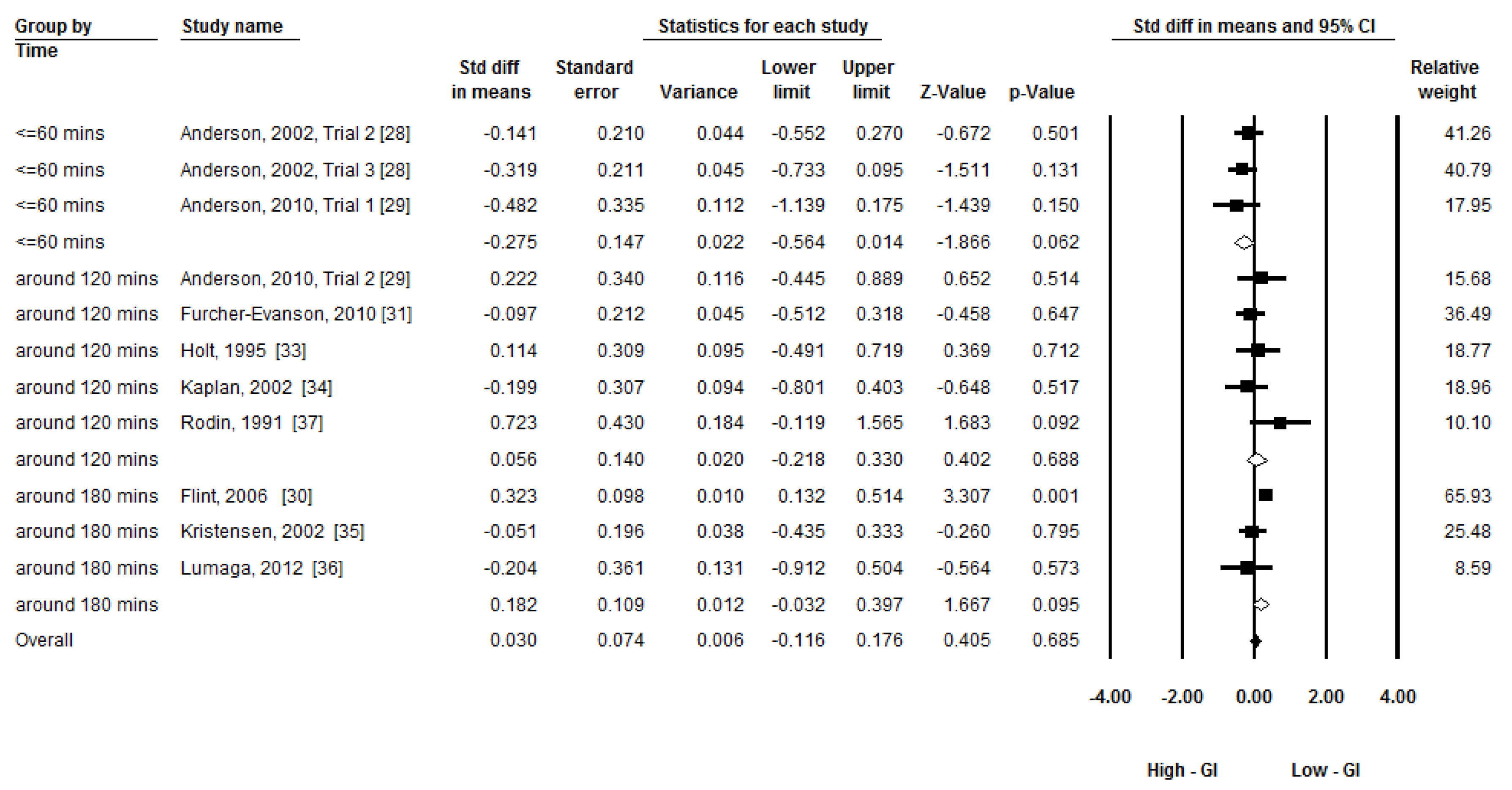

3.6. Additional Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jenkins, D.J.A.; Wolever, T.M.S.; Taylor, R.H.; Barker, H.; Fielden, H.; Baldwin, J.M.; Bowling, A.C.; Newman, H.C.; Jenkins, A.L.; Goff, D.V. Glycemic index of foods: A physiological basis for carbohydrate exchange. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1981, 34, 362–366. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brand-Miller, J.C.; Foster-Powell, K.; Colagiuri, S.; Leeds, A. The Gi Factor; Hodder Headline: Rydalmere, Australia, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Brouns, F.; Bjorck, I.; Frayn, K.N.; Gibbs, A.L.; Lang, V.; Slama, G.; Wolever, T.M.S. Glycaemic index methodology. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2005, 18, 145–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand-Miller, J.C.; Stockmann, K.; Atkinson, F.; Petocz, P.; Denyer, G.S. Glycemic index, postprandial glycemia, and the shape of the curve in healthy subjects: Analysis of a database of more than 1000 foods. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, D.E.; Elliott, E.J. Low glycaemic index, or low glycaemic load, diets for diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnagnarella, P.; Gandini, S.; la Vecchia, C.; Maisonneuve, P. Glycemic index, glycemic load, and cancer risk: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 1793–1801. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- O’Reilly, J.; Wong, S.H.S.; Chen, Y.J. Glycaemic index, glycaemic load and exercise performance. Sports Med. 2010, 40, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barclay, A.W.; Petocz, P.; McMillan-Price, J.; Flood, V.M.; Prvan, T.; Mitchell, P.; Brand-Miller, J.C. Glycemic index, glycemic load, and chronic disease risk—A meta-analysis of observational studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bornet, F.R.J.; Jardy-Gennetier, A.E.; Jacquet, N.; Stowell, J. Glycaemic response to foods: Impact on satiety and long-term weight regulation. Appetite 2007, 49, 535–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livesey, G. Low-glycaemic diets and health: Implications for obesity. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2005, 64, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, D.E.; Elliott, E.J.; Baur, L. Low glycaemic index or low glycaemic load diets for overweight and obesity. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J. Glucostatic mechanism of regulation of food intake. N. Engl. J. Med. 1953, 249, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaput, J.P.; Tremblay, A. The glucostatic theory of appetite control and the risk of obesity and diabetes. Int. J. Obes. 2009, 33, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arumugam, V.; Lee, J.S.; Nowak, J.K.; Pohle, R.J.; Nyrop, J.E.; Leddy, J.J.; Pelkman, C.L. A high-glycemic meal pattern elicited increased subjective appetite sensations in overweight and obese women. Appetite 2008, 50, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, F.J.; Campfield, L.A. Meal initiation occurs after experimental induction of transient declines in blood glucose. Am. J. Physiol. 1993, 265, R1423–R1429. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pawlak, D.B.; Ebbeling, C.B.; Ludwig, D.S. Should obese patients be counselled to follow a low-glycaemic index diet? Yes. Obes. Rev. 2002, 3, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raben, A. Should obese patients be counselled to follow a low-glycaemic index diet? No. Obes. Rev. 2002, 3, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmeron, J.; Manson, J.E.; Stampfer, M.J.; Colditz, G.A.; Wing, A.L.; Willett, W.C. Dietary fiber, glycemic load, and risk of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in women. JAMA 1997, 277, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmeron, J.; Ascherio, A.; Rimm, E.B.; Colditz, G.A.; Spiegelman, D.; Jenkins, D.J.; Stampfer, M.J.; Wing, A.L.; Willett, W.C. Dietary fiber, glycemic load, and risk of NIDDM in men. Diabetes Care 1997, 20, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, D.J.A.; Wolever, T.M.S.; Taylor, R.H.; Griffiths, C.; Krzeminska, K.; Lawrie, J.A.; Bennett, C.M.; Goff, D.V.; Sarson, D.L.; Bloom, S.R. Slow release dietary carbohydrate improves second meal tolerance. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1982, 35, 1339–1346. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The prisma statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, S.B. Glycemic index and satiety. Nutr. Clin. Care 2002, 6, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Jadad, A.R.; Moore, A.R.; Carroll, D.; Jenkinson, C.; Reynolds, J.D.M.; Gavaghan, D.J.; McQuay, H.J. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary? Controll. Clin. Trials 1996, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Li, Q.; Chu, J.; Zeng, W.; Yang, M.; Zhu, S. Effect of n−3 PUFA supplementation on cognitive function throughout the life span from infancy to old age: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 1422–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.H.; Myung, S.K.; Jeon, Y.J.; Kim, Y.; Chang, Y.J.; Ju, W.; Seo, H.G.; Huh, B.Y. Effects of selenium supplements on cancer prevention: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr. Cancer 2011, 63, 1185–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Green, S.; Collaboration, C. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, G.H.; Catherine, N.L.A.; Woodend, D.M.; Wolever, T.M.S. Inverse association between the effect of carbohydrates on blood glucose and subsequent short-term food intake in young men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 76, 1023–1030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Anderson, G.H.; Cho, C.E.; Akhavan, T.; Mollard, R.C.; Luhovyy, B.L.; Finocchiaro, E.T. Relation between estimates of cornstarch digestibility by the englyst in vitro method and glycemic response, subjective appetite, and short-term food intake in young men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 932–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flint, A.; Moller, B.K.; Raben, A.; Sloth, B.; Pedersen, D.; Tetens, I.; Holst, J.J.; Astrup, A. Glycemic and insulinemic responses as determinants of appetite in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 84, 1365–1373. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Furchner-Evanson, A.; Petrisko, Y.; Howarth, L.; Nemoseck, T.; Kern, M. Type of snack influences satiety responses in adult women. Appetite 2010, 54, 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, R.S.; Thomas, S.J.; Johns, S.K. Australian sweet lupin flour addition reduces the glycaemic index of a white bread breakfast without affecting palatability in healthy human volunteers. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 14, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Holt, S.H.A.; Miller, J.B. Increased insulin responses to ingested foods are associated with lessened satiety. Appetite 1995, 24, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.J.; Greenwood, C.E. Influence of dietary carbohydrates and glycaemic response on subjective appetite and food intake in healthy elderly persons. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2002, 53, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristensen, M.; Jensen, M.G.; Riboldi, G.; Petronio, M.; Bugel, S.; Toubro, S.; Tetens, I.; Astrup, A. Wholegrain vs. Refined wheat bread and pasta: Effect on postprandial glycemia, appetite, and subsequent ad libitum energy intake in young healthy adults. Appetite 2010, 54, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lumaga, R.B.; Azzali, D.; Fogliano, V.; Scalfi, L.; Vitaglione, P. Sugar and dietary fibre composition influence, by different hormonal response, the satiating capacity of a fruit-based and a β-glucan-enriched beverage. Food Funct. 2012, 3, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodin, J. Effects of pure sugar vs. mixed starch fructose loads on food-intake. Appetite 1991, 17, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvonen, K.R.; Purhonen, A.K.; Salmenkallio-Marttila, M.; Lahteenmaki, L.; Laaksonen, D.E.; Herzig, K.H.; Uusitupa, M.I.J.; Poutanen, K.S.; Karhunen, L.J. Viscosity of oat bran-enriched beverages influences gastrointestinal hormonal responses in healthy humans. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, I.M.; Goble, E.A.; Wittert, G.A.; Morley, J.E.; Horowitz, M. Effect of intravenous glucose and euglycemic insulin infusions on short-term appetite and food intake. Am. J. Physiol. 1998, 274, R596–R603. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eelderink, C.; Schepers, M.; Preston, T.; Vonk, R.J.; Oudhuis, L.; Priebe, M.G. Slowly and rapidly digestible starchy foods can elicit a similar glycemic response because of differential tissue glucose uptake in healthy men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 96, 1017–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornier, M.A.; Grunwald, G.K.; Johnson, S.L.; Bessesen, D.H. Effects of short-term overfeeding on hunger, satiety, and energy intake in thin and reduced-obese individuals. Appetite 2004, 43, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Westerterp-Plantenga, M.S.; Lejeune, M.P.G.M.; Smeets, A.J.P.G.; Luscombe-Marsh, N.D. Sex differences in energy homeostatis following a diet relatively high in protein exchanged with carbohydrate, assessed in a respiration chamber in humans. Physiol. Behav. 2009, 97, 414–419. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Asarian, L.; Geary, N. Modulation of appetite by gonadal steroid hormones. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2006, 361, 1251–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafar, T.A.; Kabir, Y.; Ghazaii, C. Low glycemic index foods suppress glycemic responses, appetite and food intake in young Kuwaiti females. Kuwait J. Sci. Eng. 2011, 38, 111–123. [Google Scholar]

- Zafar, T.A.; Waslien, C.; AlRaefaei, A.; Alrashidi, N.; AlMahmoud, E. Whey protein sweetened beverages reduce glycemic and appetite responses and food intake in young females. Nutr. Res. 2013, 33, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhri, O.B.; Salem, V.; Murphy, K.G.; Bloom, S.R. Gastrointestinal satiety signals. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2008, 70, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, S.C. Gastrointestinal satiety signals I.—An overview of gastrointestinal signals that influence food intake. Am. J. Physiol. 2004, 286, G7–G13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, G.H.; Woodend, D. Effect of glycemic carbohydrates on short-term satiety and food intake. Nutr. Rev. 2003, 61, S17–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolever, T.M.S.; Cohen, Z.; Thompson, L.U.; Thorne, M.J.; Jenkins, M.J.; Prokipchuk, E.J.; Jenkins, D.J.A. Ileal loss of available carbohydrate in man: Comparison of a breath hydrogen method with direct measurement using a human ileostomy model. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1986, 81, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, D.J.A.; Cuff, D.; Wolever, T.M.S.; Knowland, D.; Thompson, L.; Cohen, Z.; Prokipchuk, E. Digestibility of carbohydrate foods in an ileostomate: Relationship to dietary fiber, in vitro digestibility, and glycemic response. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1987, 82, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, D.J.A.; Wolever, T.M.S.; Collier, G.R.; Ocana, A.; Rao, A.V.; Buckley, G.; Lam, Y.; Mayer, A.; Thompson, L.U. Metabolic effects of a low-glycemic-index diet. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1987, 46, 968–975. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wolever, T.M.S.; Jenkins, D.J.A.; Vuksan, V.; Jenkins, A.L.; Buckley, G.C.; Wong, G.S.; Josse, R.G. Beneficial effect of a low glycaemic index diet in type 2 diabetes. Diabet. Med. 1992, 9, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Champ, M.; Langkilde, A.M.; Brouns, F.; Kettlitz, B.; le Bail-Collet, Y. Advances in dietary fibre characterisation. 2. Consumption, chemistry, physiology and measurement of resistant starch; implications for health and food labelling. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2003, 16, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, H.; Frost, G. Glycaemic index, appetite and body weight. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2010, 69, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lennerz, B.S.; Alsop, D.C.; Holsen, L.M.; Stern, E.; Rojas, R.; Ebbeling, C.B.; Goldstein, J.M.; Ludwig, D.S. Effects of dietary glycemic index on brain regions related to reward and craving in men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 98, 641–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sloth, B.; Astrup, A. Low glycemic index diets and body weight. Int. J. Obes. 2006, 30, S47–S51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niwano, Y.; Adachi, T.; Kashimura, J.; Sakata, T.; Sasaki, H.; Sekine, K.; Yamamoto, S.; Yonekubo, A.; Kimura, S. Is glycemic index of food a feasible predictor of appetite, hunger, and satiety? J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2009, 55, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dansinger, M.L.; Tatsioni, A.; Wong, J.B.; Chung, M.; Balk, E.M. Meta-analysis: The effect of dietary counseling for weight loss. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007, 147, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, S.C.; Seeley, R.J.; Porte, D.; Schwartz, M.W. Signals that regulate food intake and energy homeostasis. Science 1998, 280, 1378–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, F.-H.; Li, C.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Wong, S.H.-S.; Wang, L. Effect of Glycemic Index of Breakfast on Energy Intake at Subsequent Meal among Healthy People: A Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2016, 8, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8010037

Sun F-H, Li C, Zhang Y-J, Wong SH-S, Wang L. Effect of Glycemic Index of Breakfast on Energy Intake at Subsequent Meal among Healthy People: A Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2016; 8(1):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8010037

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Feng-Hua, Chunxiao Li, Yan-Jie Zhang, Stephen Heung-Sang Wong, and Lin Wang. 2016. "Effect of Glycemic Index of Breakfast on Energy Intake at Subsequent Meal among Healthy People: A Meta-Analysis" Nutrients 8, no. 1: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8010037

APA StyleSun, F.-H., Li, C., Zhang, Y.-J., Wong, S. H.-S., & Wang, L. (2016). Effect of Glycemic Index of Breakfast on Energy Intake at Subsequent Meal among Healthy People: A Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 8(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8010037