Contribution of Organic Food to the Diet in a Large Sample of French Adults (the NutriNet-Santé Cohort Study)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Ethics

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.3.1. Assessment of Individual Characteristics

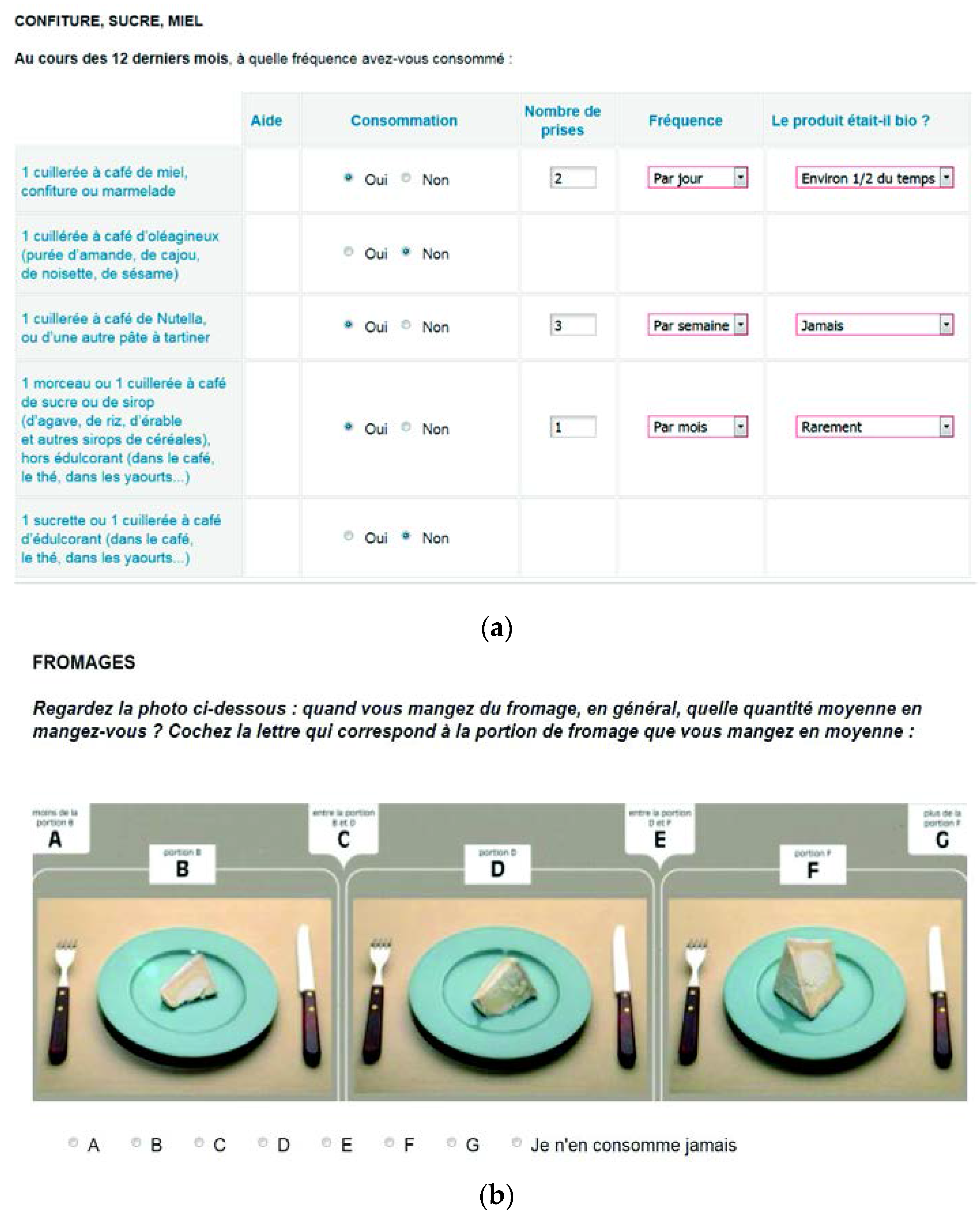

2.3.2. Organic Food Frequency Questionnaire: Org-FFQ

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Study Population

| Women | Men | p * | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean or % | SD | Mean or % | SD | ||

| N—not weighted % | 20,980 (74.28) | 7265 (25.72) | |||

| N—weighted % | 14,788.40 (47.64) | 13,456.60 (52.36) | |||

| Age (years) | 48.65 | 13.88 | 47.39 | 21.92 | <0.0001 |

| Educational level | <0.0001 | ||||

| <High school diploma | 58.39 | 61.25 | |||

| High school | 16.07 | 14.56 | |||

| Post-secondary graduate | 25.54 | 24.19 | |||

| Income per household unit † | <0.0001 | ||||

| <1.200 euros | 24.68 | 23.85 | |||

| 1.200–1800 euros | 25.50 | 24.17 | |||

| 1.800–2.700 euros | 22.04 | 24.72 | |||

| >2700 euros | 10.66 | 15.83 | |||

| Missing | 17.12 | 11.43 | |||

| Socio-professional categories | <0.0001 | ||||

| Farmer | 0.55 | 1.53 | |||

| Craftsman, shopkeeper, business owner | 1.87 | 5.14 | |||

| Non employed | 7.74 | 1.32 | |||

| Employee | 25.31 | 8.41 | |||

| Student | 4.60 | 4.40 | |||

| Manual worker | 5.22 | 23.49 | |||

| Intermediate profession | 14.47 | 14.53 | |||

| Retired | 28.61 | 26.12 | |||

| Managerial staff | 4.89 | 3.37 | |||

| Location | <0.0001 | ||||

| Rural community | 24.60 | 26.23 | |||

| Urban unit with a population smaller than 20,000 inhabitants | 15.32 | 15.13 | |||

| Urban unit with a population between 20,000 and 200,000 inhabitants | 16.22 | 16.85 | |||

| Urban unit with a population higher than 200,000 inhabitants | 43.86 | 41.79 | |||

| Smoking status | <0.0001 | ||||

| Never smoker | 52.66 | 41.56 | |||

| Former smoker | 33.78 | 42.94 | |||

| Current smoker | 13.56 | 15.50 | |||

| Physical activity | <0.0001 | ||||

| High | 20.92 | 16.83 | |||

| Medium | 34.02 | 29.20 | |||

| Low | 31.58 | 37.87 | |||

| Missing | 13.48 | 16.10 | |||

| Vegetarian diet | 2.88 | 1.53 | <0.0001 | ||

| Vegan diet | 3.25 | 2.93 | 0.12 | ||

| Location | <0.0001 | ||||

| Rural community | 24.60 | 26.23 | |||

| Urban unit with a population smaller than 20,000 inhabitants | 15.32 | 15.13 | |||

| Urban unit with a population between 20,000 and 200,000 inhabitants | 16.22 | 16.85 | |||

| Urban unit with a population higher than 200,000 inhabitants | 43.86 | 41.79 | |||

3.2. Percentage of Organic Food Consumers by Food Group

3.3. Contribution of Organic Food to the Whole Diet by Gender

3.4. Contribution of Organic Food to Food Groups

3.5. Top 10 Organic Food Items

3.6. Contribution of Organic Food to the Whole Diet According to Several Sociodemographic and Lifestyle Factors

| Women | Men | p * | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 20,980 | n = 7265 | ||||||||||||

| Total | Organic | Ratio | Total | Organic | Ratio | ||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Total Intake (g/day) | 3408.34 | 949.91 | 695.62 | 673.35 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 3497.16 | 1666.2 | 621.79 | 1002.10 | 0.18 | 0.28 | <0.0001 |

| Liquid intake (g/day) † | 1108.00 | 461.83 | 290.20 | 328.16 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 1130.69 | 825.85 | 255.77 | 499.49 | 0.23 | 0.40 | <0.0001 |

| Solid intake (g/day) ‡ | 1360.44 | 478.29 | 405.42 | 425.18 | 0.28 | 0.23 | 1396.72 | 812.46 | 366.02 | 624.75 | 0.25 | 0.38 | <0.0001 |

| Water intake (g/day) | 939.90 | 44.34 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 969.75 | 982.85 | NA | NA | NA | NA | / |

| Total intake (kcal/day) | 1979.06 | 539.19 | 537.74 | 502.91 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 2280.27 | 1016.5 | 546.54 | 852.48 | 0.24 | 0.36 | <0.0001 |

| Liquid intake (kcal/day) † | 198.16 | 121.83 | 53.17 | 70.74 | 0.27 | 0.25 | 246.58 | 248.59 | 56.71 | 125.54 | 0.23 | 0.39 | <0.0001 |

| Solid intake (kcal/day) ‡ | 1780.90 | 05.72 | 484.57 | 460.07 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 2033.69 | 955.08 | 489.83 | 776.98 | 0.24 | 0.36 | <0.0001 |

| Food groups | Women | Men | p § | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 20,980 | n = 7265 | ||||||||||||||||

| N * | N † | Total | Organic | Ratio ‡ | N * | N † | Total | Organic | Ratio ‡ | ||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||||

| Vegetables | 20962 | 14778.38 | 277.93 | 187.84 | 107.36 | 158.41 | 0.31 | 0.27 | 7253 | 13443.91 | 254.34 | 260.31 | 83.43 | 185.50 | 0.28 | 0.44 | <0.0001 |

| Soup | 19697 | 13327.17 | 84.52 | 89.28 | 34.12 | 58.14 | 0.34 | 0.30 | 6426 | 10818.15 | 54.22 | 123.81 | 19.24 | 71.63 | 0.33 | 0.46 | 0.0017 |

| Fruits | 20925 | 14710.15 | 320.03 | 274.75 | 99.73 | 148.55 | 0.29 | 0.26 | 7241 | 13212.14 | 249.30 | 389.33 | 75.42 | 228.72 | 0.28 | 0.44 | 0.0102 |

| Fruit juice | 16865 | 11268.17 | 84.66 | 95.29 | 27.53 | 49.92 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 5803 | 10418.84 | 87.40 | 161.38 | 28.78 | 95.16 | 0.29 | 0.46 | <0.0001 |

| Nuts | 15781 | 10032.06 | 3.59 | 6.54 | 1.78 | 4.44 | 0.35 | 0.30 | 5178 | 8248.876 | 2.42 | 8.35 | 1.15 | 5.88 | 0.33 | 0.48 | 0.0007 |

| Meat | 19801 | 13404.12 | 57.16 | 48.26 | 9.49 | 16.72 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 7013 | 12613.52 | 88.87 | 143.19 | 14.25 | 39.64 | 0.18 | 0.35 | 0.9520 |

| Processed meat | 19694 | 13236.63 | 29.48 | 24.09 | 4.06 | 7.60 | 0.15 | 0.19 | 6973 | 12375.27 | 40.05 | 48.38 | 6.48 | 19.82 | 0.16 | 0.32 | 0.0074 |

| Fish | 20161 | 13622.62 | 41.56 | 36.46 | 6.32 | 12.24 | 0.15 | 0.19 | 6994 | 11930.79 | 40.75 | 63.88 | 7.44 | 27.53 | 0.16 | 0.33 | 0.0015 |

| Poultry | 19849 | 13437.17 | 23.44 | 22.41 | 5.50 | 8.72 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 6964 | 12537.7 | 27.95 | 43.61 | 6.35 | 15.22 | 0.26 | 0.42 | 0.0006 |

| Eggs | 20095 | 13743.7 | 11.40 | 10.11 | 6.17 | 7.83 | 0.52 | 0.34 | 6972 | 12698.54 | 14.17 | 40.41 | 5.14 | 14.58 | 0.40 | 0.54 | <0.0001 |

| Milk | 6895 | 5038.406 | 63.76 | 117.71 | 15.32 | 53.17 | 0.29 | 0.32 | 2276 | 5015.25 | 67.56 | 196.43 | 17.29 | 94.05 | 0.28 | 0.56 | 0.3421 |

| Dairy products | 19444 | 13286.39 | 162.75 | 129.79 | 33.94 | 56.95 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 6551 | 11963.28 | 134.93 | 173.31 | 25.89 | 72.39 | 0.23 | 0.44 | 0.0015 |

| Cheese | 20283 | 13936.1 | 36.81 | 35.31 | 5.15 | 10.53 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 7009 | 12699.95 | 46.03 | 65.88 | 7.63 | 23.52 | 0.17 | 0.33 | <0.0001 |

| Milky desserts | 15110 | 9678.505 | 12.02 | 23.16 | 1.56 | 7.47 | 0.14 | 0.21 | 4994 | 8301.999 | 11.99 | 31.79 | 1.10 | 6.20 | 0.12 | 0.30 | <0.0001 |

| Potatoes | 20773 | 14660.22 | 21.32 | 18.13 | 6.15 | 11.12 | 0.28 | 0.30 | 7216 | 13266.06 | 35.44 | 65.71 | 8.36 | 19.84 | 0.26 | 0.46 | 0.0001 |

| Bread | 17942 | 12361.84 | 46.53 | 44.39 | 6.00 | 13.22 | 0.16 | 0.21 | 6118 | 11568.34 | 67.80 | 86.71 | 9.23 | 31.26 | 0.16 | 0.34 | 0.1516 |

| Cereals || | 20844 | 14673.23 | 77.51 | 59.03 | 20.58 | 34.06 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 7184 | 13386.24 | 112.95 | 140.97 | 25.73 | 70.35 | 0.24 | 0.45 | <0.0001 |

| Wholegrain products ¶ | 17489 | 11521.01 | 58.28 | 73.68 | 28.03 | 52.53 | 0.37 | 0.30 | 5521 | 9193.965 | 52.27 | 113.79 | 28.01 | 95.61 | 0.37 | 0.48 | 0.7229 |

| Oil | 20744 | 14489.61 | 19.86 | 14.22 | 7.99 | 10.91 | 0.36 | 0.32 | 7146 | 12882.69 | 17.21 | 26.80 | 6.42 | 14.90 | 0.33 | 0.51 | <0.0001 |

| Cookies | 19032 | 13175.31 | 11.11 | 17.47 | 1.24 | 3.73 | 0.15 | 0.22 | 6512 | 11538.17 | 14.10 | 28.95 | 1.46 | 6.58 | 0.13 | 0.31 | <0.0001 |

| Nonalcoholic drinks ** | 20978 | 14786.7 | 1680.03 | 708.18 | 182.76 | 256.34 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 7262 | 13454.84 | 1668.14 | 1220.4 | 143.17 | 358.47 | 0.09 | 0.20 | <0.0001 |

| Sweet | 20925 | 14743.73 | 46.51 | 35.03 | 11.66 | 19.98 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 7241 | 13229.96 | 54.53 | 59.74 | 12.38 | 25.75 | 0.24 | 0.38 | 0.0238 |

| Fast food | 20371 | 14204.8 | 31.03 | 25.10 | 5.05 | 9.42 | 0.17 | 0.22 | 7050 | 12767.22 | 65.60 | 311.61 | 11.65 | 78.03 | 0.15 | 0.32 | <0.0001 |

| Meat substitutes | 6796 | 4428.214 | 7.94 | 21.50 | 7.02 | 19.74 | 0.81 | 0.26 | 1654 | 3306.038 | 6.24 | 35.34 | 5.17 | 32.39 | 0.76 | 0.52 | <0.0001 |

| Dressing | 20489 | 14275.82 | 7.15 | 6.92 | 1.50 | 3.57 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 7088 | 12758.5 | 7.69 | 11.97 | 1.42 | 5.09 | 0.20 | 0.39 | <0.0001 |

| Alcohol | 19069 | 12420.19 | 60.02 | 81.41 | 9.16 | 25.87 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 6892 | 12177.21 | 136.47 | 256.24 | 20.95 | 72.25 | 0.16 | 0.31 | <0.0001 |

| Snacks | 19666 | 13358.92 | 9.91 | 11.92 | 3.13 | 7.96 | 0.19 | 0.25 | 6798 | 12325.1 | 10.00 | 24.07 | 2.47 | 11.48 | 0.17 | 0.37 | <0.0001 |

| Grains | 9325 | 5780.877 | 3.70 | 8.19 | 2.90 | 7.03 | 0.70 | 0.31 | 2279 | 4429.612 | 2.12 | 9.56 | 1.63 | 8.19 | 0.64 | 0.55 | <0.0001 |

| Other fats †† | 19798 | 13777.13 | 4.01 | 5.48 | 1.00 | 2.38 | 0.25 | 0.29 | 6521 | 11510.38 | 2.79 | 5.70 | 0.83 | 3.49 | 0.23 | 0.43 | <0.0001 |

| Dairy substitutes ‡‡ | 6170 | 3992.64 | 30.90 | 81.47 | 25.10 | 73.05 | 0.63 | 0.33 | 1487 | 2864.714 | 30.40 | 157.46 | 25.40 | 146.82 | 0.65 | 0.58 | 0.1721 |

| Legumes | 18809 | 12558.85 | 20.21 | 42.80 | 12.18 | 41.06 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 6521 | 11104 | 20.53 | 48.81 | 9.04 | 41.63 | 0.28 | 0.47 | <0.0001 |

| Soda | 14716 | 10210.88 | 56.59 | 117.15 | 4.72 | 23.04 | 0.11 | 0.20 | 4919 | 10124.65 | 66.25 | 206.90 | 7.44 | 42.63 | 0.13 | 0.36 | <0.0001 |

| In Terms of Number of Consumers | N * | In Terms of Weight †,‡ | g/day | In Terms of Contribution in the Intake § | % | N * | In Terms of Frequency per day † | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women n = 20,980 | |||||||||

| 1 | fried eggs | 9192 | apple | 23.31 | linseed oil | 92 | 573 | honey, jam | 0.35 |

| 2 | hard boiled eggs | 8754 | green salad | 20.02 | kombucha | 91 | 179 | olive oil | 0.33 |

| 3 | tomato | 8655 | tomato | 17.08 | vegan chorizo | 90 | 626 | tea | 0.27 |

| 4 | honey, jam | 8328 | whole bread | 13.91 | soy milk | 90 | 1979 | whole bread | 0.25 |

| 5 | cucumber | 8096 | legumes | 12.18 | vegan pâté | 89 | 1111 | herbal tea | 0.20 |

| 6 | olive oil | 7949 | citrus fruit | 11.51 | vegan fresh cheese | 89 | 14089 | green salad | 0.20 |

| 7 | green salad | 7948 | full fat yoghurt | 11.01 | seitan | 89 | 831 | chocolate | 0.17 |

| 8 | strawberry | 7775 | cucumber | 10.3 | vegan galette | 88 | 2636 | black coffee | 0.16 |

| 9 | peas | 7719 | peach | 9.71 | sprouted seeds | 87 | 1332 | tomato | 0.16 |

| 10 | apple | 7715 | whole rice | 9.46 | safflower oil | 87 | 134 | spreadable butter | 0.15 |

| Men n = 7265 | |||||||||

| 1 | fried eggs | 7367 | apple | 21.16 | seitan | 98 | 695 | honey, jam | 0.39 |

| 2 | tomato | 7215 | green salad | 15.28 | vegan fresh cheese | 98 | 341 | whole bread | 0.28 |

| 3 | honey, jam | 6889 | whole bread | 15.14 | coconut oil | 97 | 360 | olive oil | 0.27 |

| 4 | olive oil | 6788 | tomato | 13.96 | vegan pâté | 96 | 981 | black coffee | 0.22 |

| 5 | apple | 6570 | banana | 9.99 | vegetal-based cheese | 95 | 254 | chocolate | 0.19 |

| 6 | green salad | 6500 | legumes | 9.04 | kombucha | 94 | 369 | tea | 0.18 |

| 7 | strawberry | 6477 | white bread | 8.74 | linseed oil | 93 | 427 | white bread | 0.16 |

| 8 | peas | 6452 | pasta | 8.32 | soy-based cheese | 92 | 225 | green salad | 0.14 |

| 9 | cucumber | 6429 | full fat yoghurt | 8.25 | vegan chorizo | 91 | 408 | spreadable butter | 0.14 |

| 10 | carrot | 6216 | carrot | 7.98 | vegan galette | 89 | 1349 | apple | 0.13 |

| Weighted % | Ratio | p * | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Median | |||

| Gender | <0.0001 | ||||

| Women | 47.64 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.14 | |

| Men | 52.36 | 0.18 | 0.28 | 0.10 | |

| Age | <0.0001 | ||||

| ≤Median age (48 years old) | 50.10 | 0.18 | 0.25 | 0.11 | |

| >Median age (48 years old) | 49.90 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.13 | |

| Education | <0.0001 | ||||

| <High school diploma | 75.11 | 0.18 | 0.30 | 0.10 | |

| ≥High school diploma | 24.89 | 0.21 | 0.13 | 0.16 | |

| Income | <0.0001 | ||||

| <1800 euros | 57.43 | 0.17 | 0.25 | 0.09 | |

| ≥1800 euros | 42.57 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.16 | |

| Location | <0.0001 | ||||

| Rural area | 25.44 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.13 | |

| Urban area (community ≥ 5000 inhabitants) | 74.56 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.12 | |

| Physical activity | <0.0001 | ||||

| <30 min brisk walking/day | 22.25 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.07 | |

| ≥30 min brisk walking/day | 77.75 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.16 | |

| Type of diet | <0.0001 | ||||

| Meat eaters | 94.67 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.11 | |

| Vegetarians and vegans | 5.33 | 0.47 | 0.29 | 0.48 | |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Foley, J.A.; DeFries, R.; Asner, G.P.; Barford, C.; Bonan, G.; Carpenter, S.R.; Chapin, F.S.; Coe, M.T.; Daily, G.C.; Gibbs, H.K.; et al. Global consequences of land use. Science 2005, 309, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases. Available online: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/publications/trs916/en/gsfao_introduction.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2015).

- Gomiero, T.; Pimentel, D.; Paoletti, M.G. Environmental impact of different agricultural management practices: conventional vs. organic agriculture. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2011, 30, 95–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, D.; Hepperly, P.; Hanson, J.; Douds, D.; Seidel, R. Environmental, energetic, and economic comparisons of organic and conventional farming systems. BioScience 2005, 55, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomisto, H.L.; Hodge, I.D.; Riordan, P.; Macdonald, D.W. Does organic farming reduce environmental impacts?—A meta-analysis of European research. J. Environ. Manage. 2012, 112, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agriculture Biologique et Environnement: Des Enjeux Convergents. Available online: http://www.synabio.com/doc/synabio-doc-359.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2015).

- Bengtsson, J.; Ahnström, J.; Weibull, A.-C. The effects of organic agriculture on biodiversity and abundance: A meta-analysis: Organic agriculture, biodiversity and abundance. J. Appl. Ecol. 2005, 42, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughner, R.S.; McDonagh, P.; Prothero, A.; Shultz, C.J.; Stanton, J. Who are organic food consumers? A compilation and review of why people purchase organic food. J. Consum. Behav. 2007, 6, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjelmar, U. Consumers’ purchase of organic food products. A matter of convenience and reflexive practices. Appetite 2011, 56, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baromètre de Consommation et de Perception des Produits Biologiques en France. Available online: http://www.agencebio.org/sites/default/files/upload/documents/4_Chiffres/BarometreConso/barometre_agence_bio_public.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2015).

- Barański, M.; Średnicka-Tober, D.; Volakakis, N.; Seal, C.; Sanderson, R.; Stewart, G.B.; Benbrook, C.; Biavati, B.; Markellou, E.; Giotis, C.; et al. Higher antioxidant and lower cadmium concentrations and lower incidence of pesticide residues in organically grown crops: A systematic literature review and meta-analyses. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 112, 794–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lairon, D.; Huber, M. Food Quality and Possible Positive Health Effects of Organic Products. In Organic Farming, Prototype for Sustainable Agricultures; Bellon, S., Penvern, S., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 295–312. [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Spangler, C.; Brandeau, M.L.; Hunter, G.E.; Bavinger, J.C.; Pearson, M.; Eschbach, P.J.; Sundaram, V.; Liu, H.; Schirmer, P.; Stave, C.; et al. Are organic foods safer or healthier than conventional alternatives? A systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2012, 157, 348–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, M.; Rembiałkowska, E.; Średnicka, D.; Bügel, S.; van de Vijver, L.P.L. Organic food and impact on human health: Assessing the status quo and prospects of research. NJAS—Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2011, 58, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comparison of composition (nutrients and other substances) of organically and conventionally produced foodstuffs: A systematic review of the available literature. Available online: https://www.schweine.net/services/files/7_org.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2014).

- Alfvén, T.; Braun-Fahrländer, C.; Brunekreef, B.; von Mutius, E.; Riedler, J.; Scheynius, A.; van Hage, M.; Wickman, M.; Benz, M.R.; Budde, J.; et al. Allergic diseases and atopic sensitization in children related to farming and anthroposophic lifestyle—the PARSIFAL study. Allergy 2006, 61, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradbury, K.E.; Balkwill, A.; Spencer, E.A.; Roddam, A.W.; Reeves, G.K.; Green, J.; Key, T.J.; Beral, V.; Pirie, K.; Banks, E.; et al. Organic food consumption and the incidence of cancer in a large prospective study of women in the United Kingdom. Br. J. Cancer 2014, 110, 2321–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oates, L.; Cohen, M.; Braun, L.; Schembri, A.; Taskova, R. Reduction in urinary organophosphate pesticide metabolites in adults after a week-long organic diet. Environ. Res. 2014, 132, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torjusen, H.; Brantsæter, A.L.; Haugen, M.; Alexander, J.; Bakketeig, L.S.; Lieblein, G.; Stigum, H.; Næs, T.; Swartz, J.; Holmboe-Ottesen, G.; et al. Reduced risk of pre-eclampsia with organic vegetable consumption: Results from the prospective Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e006143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curl, C.L.; Beresford, S.A.A.; Fenske, R.A.; Fitzpatrick, A.L.; Lu, C.; Nettleton, J.A.; Kaufman, J.D. Estimating pesticide exposure from dietary intake and organic food choices: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Environ. Health Perspect. 2015, 123, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The World of Organic Agriculture. Available online: https://www.fibl.org/fileadmin/documents/shop/1663-organic-world-2015.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2015).

- La Bio Poursuit Son Développement et Accroît Son Rayonnement Aupres Des Francais. Available online: http://www.agencebio.org/sites/default/files/upload/dp_conf_de_presse_18_02_2015_val.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2015).

- OrganicDataNetwork—Organic Crops: Area and Production Data for Selected Crops. Available online: http://www.organicdatanetwork.net/odn-statistics/odn-statistics-data/odn-statistics-data-crops.html?L=0 (accessed on 15 September 2015).

- Agence Bio La Bio en France: De la Production à la Consommation. Available online: http://www.agencebio.org/sites/default/files/upload/documents/4_Chiffres/BrochureCC/CC2013_chap4_France.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2015).

- Kesse-Guyot, E.; Péneau, S.; Méjean, C.; Szabo de Edelenyi, F.; Galan, P.; Hercberg, S.; Lairon, D. Profiles of organic food consumers in a large sample of French adults: Results from the Nutrinet-santé cohort study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torjusen, H.; Lieblein, G.; Naes, T.; Haugen, M.; Meltzer, H.M.; Brantsaeter, A.L. Food patterns and dietary quality associated with organic food consumption during pregnancy; data from a large cohort of pregnant women in Norway. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, S.B.; Rasmussen, M.A.; Strøm, M.; Halldorsson, T.I.; Olsen, S.F. Sociodemographic characteristics and food habits of organic consumers—A study from the Danish National Birth Cohort. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 1810–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisinger-Watzl, M.; Wittig, F.; Heuer, T.; Hoffmann, I. Customers purchasing organic food—Do they live healthier? Results of the German national nutrition survey II. Eur. J. Nutr. Food Saf. 2015, 5, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oates, L.; Cohen, M.; Braun, L. Characteristics and consumption patterns of Australian organic consumers. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2012, 92, 2782–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockie, S.; Lyons, K.; Lawrence, G.; Grice, J. Choosing organics: A path analysis of factors underlying the selection of organic food among Australian consumers. Appetite 2004, 43, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivas, R.; Bernabéu, R. Men’s and women’s attitudes toward organic food consumption. A Spanish case study. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2012, 10, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hercberg, S.; Castetbon, K.; Czernichow, S.; Malon, A.; Mejean, C.; Kesse, E.; Touvier, M.; Galan, P. The Nutrinet-Santé Study: A web-based prospective study on the relationship between nutrition and health and determinants of dietary patterns and nutritional status. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touvier, M.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Méjean, C.; Pollet, C.; Malon, A.; Castetbon, K.; Hercberg, S. Comparison between an interactive web-based self-administered 24 h dietary record and an interview by a dietitian for large-scale epidemiological studies. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 105, 1055–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touvier, M.; Méjean, C.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Pollet, C.; Malon, A.; Castetbon, K.; Hercberg, S. Comparison between web-based and paper versions of a self-administered anthropometric questionnaire. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 25, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagströmer, M.; Oja, P.; Sjöström, M. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ): A study of concurrent and construct validity. Public Health Nutr. 2006, 9, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- INSEE (Institut National de la Statistique et des Etudes Economiques) Website. Available online: http://www.insee.fr/en/methodes/ (accessed on 23 February 2015).

- Le Moullec, N.; Deheeger, M.; Preziosi, P.; Monteiro, P.; Valeix, P.; Rolland-Cachera, M.-F.; de Courcy, P.G.; Christides, J.-P.; Cherouvrier, F.; Galan, P.; et al. Validation du manuel-photos utilisé pour l’enquête alimentaire de l’étude SU.VI.MAX. Cah. Nutr. Diététique 1996, 31, 158–164. [Google Scholar]

- Kesse-Guyot, E.; Castetbon, K.; Touvier, M.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P. Relative validity and reproducibility of a food frequency questionnaire designed for French adults. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2010, 57, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubinstein, R.Y.; Kroese, D.P. Simulation and the Monte Carlo Method, Student Solutions Manual; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schofield, W.N. Predicting basal metabolic rate, new standards and review of previous work. Hum. Nutr. Clin. Nutr. 1985, 39, 5–41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- INSEE (Institut National de la Statistique et des Etudes Economiques) French National Census Data. Available online: http://www.insee.fr/fr/ppp/bases-de-donnees/recensement/populations-legales/default.asp?annee=2009 (accessed on 6 June 2013).

- Isenhour, C.; Ardenfors, M. Gender and sustainable consumption: Policy implications. Int. J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 4, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schifferstein, H.N.J.; Oude Ophuis, P.A.M. Health-related determinants of organic food consumption in The Netherlands. Food Qual. Prefer. 1998, 9, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eating “Green”: Motivations behind organic food consumption in Australia. Available online: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.gate2.inist.fr/doi/10.1111/1467–9523.00200/abstract (accessed on 15 September 2015).

- Torjusen, H.; Brantsæter, A.L.; Haugen, M.; Lieblein, G.; Stigum, H.; Roos, G.; Holmboe-Ottesen, G.; Meltzer, H.M. Characteristics associated with organic food consumption during pregnancy; data from a large cohort of pregnant women in Norway. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, D.; Henryks, J.; Jones, H. Organic food: What we know (and do not know) about consumers. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2011, 26, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Observatoire Viandes BIO 2014: Une Dynamique Toujours Positive (Interbev). Available online: http://www.revenuagricole.fr/focus-technique/conduite-et-gestion-du-troupeau/89-focus-marches/eleveur-viande/eleveur-viande-memos-debouches-filiere/14977-observatoire-viandes-bio-2014-une-dynamique-toujours-positive-interbev (accessed on 7 April 2015).

- Centre National Interprofessionnel de l’Economie Laitière Rapport annuel 2013–2014. Available online: http://infos.cniel.com/uploads/tx_hpoindexbdd/4p_bio_2014__2_.pdf (accessed on 7 April 2015).

- Andreeva, V.A.; Salanave, B.; Castetbon, K.; Deschamps, V.; Vernay, M.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Hercberg, S. Comparison of the sociodemographic characteristics of the large NutriNet-Santé e-cohort with French Census data: The issue of volunteer bias revisited. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2015, 69, 893–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebert, J.R.; Hurley, T.G.; Peterson, K.E.; Resnicow, K.; Thompson, F.E.; Yaroch, A.L.; Ehlers, M.; Midthune, D.; Williams, G.C.; Greene, G.W.; et al. Social desirability trait influences on self-reported dietary measures among diverse participants in a multicenter multiple risk factor trial. J. Nutr. 2008, 138, 226S–234S. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baudry, J.; Méjean, C.; Allès, B.; Péneau, S.; Touvier, M.; Hercberg, S.; Lairon, D.; Galan, P.; Kesse-Guyot, E. Contribution of Organic Food to the Diet in a Large Sample of French Adults (the NutriNet-Santé Cohort Study). Nutrients 2015, 7, 8615-8632. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu7105417

Baudry J, Méjean C, Allès B, Péneau S, Touvier M, Hercberg S, Lairon D, Galan P, Kesse-Guyot E. Contribution of Organic Food to the Diet in a Large Sample of French Adults (the NutriNet-Santé Cohort Study). Nutrients. 2015; 7(10):8615-8632. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu7105417

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaudry, Julia, Caroline Méjean, Benjamin Allès, Sandrine Péneau, Mathilde Touvier, Serge Hercberg, Denis Lairon, Pilar Galan, and Emmanuelle Kesse-Guyot. 2015. "Contribution of Organic Food to the Diet in a Large Sample of French Adults (the NutriNet-Santé Cohort Study)" Nutrients 7, no. 10: 8615-8632. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu7105417

APA StyleBaudry, J., Méjean, C., Allès, B., Péneau, S., Touvier, M., Hercberg, S., Lairon, D., Galan, P., & Kesse-Guyot, E. (2015). Contribution of Organic Food to the Diet in a Large Sample of French Adults (the NutriNet-Santé Cohort Study). Nutrients, 7(10), 8615-8632. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu7105417