Vitamin E Isoforms as Modulators of Lung Inflammation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

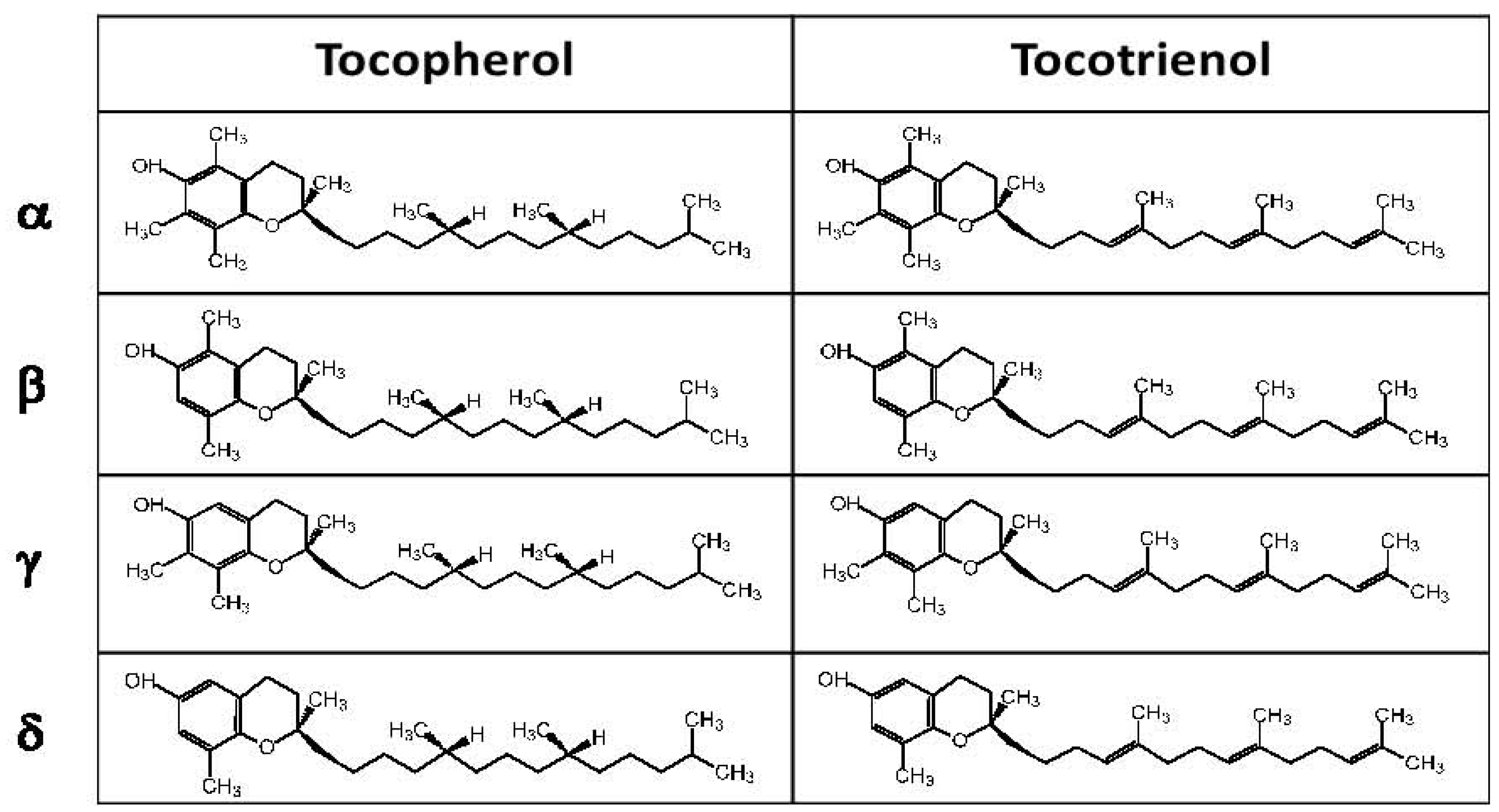

2. Versatile Nature of Vitamin E

3. Experimental Evidence for Modulation of Lung Function by Vitamin E Isoforms

| A. Animal | |||||||

| Line | Airway Inflammation/Model | αT and γT Isoforms in the Studies | Major Outcome in Airway [reference] | ||||

| Tocopherol Isoform (dose) | Tocopherol Isoform (Figure 2 and [36]) in Reported Oil Vehicle | ||||||

| 1 | Eosinophil inflammation/mouse, OVA | αT (0.2 mg/20 g mouse/day × 8 days) | no tocopherolin ethoxylated castor oil | Beneficial, Eosinophil decrease [4,5] | |||

| 2 | Eosinophil inflammation/mouse, OVA | αT (500 mg/kg diet × 45 days) | tocopherol-stripped corn oil | Beneficial, Eosinophil decrease [34] | |||

| 3 | Eosinophil inflammation/mouse, OVA | αT (10 mg/kg mouse × twice/day × 14 days) | no tocopherol in ethanol | Beneficial, Eosinophil decrease [35] | |||

| 4 | Eosinophil inflammation/mouse, OVA | γT (0.2 mg/20 g mouse/day × 8 days) | no tocopherol in ethoxylated castor oil | Detrimental, Eosinophil increase [4,5] | |||

| 5 | Eosinophil inflammation/mouse, OVA | αT and γT (0.2 mg αT + 0.2 mg γT/20 g mouse/day × 8 days) | no tocopherol in ethoxylated castor oil | No effect [4,5] | |||

| 6 | Eosinophil inflammation/rat, OVA | αT (400 mg/kg/day × 10 days) | γT in soy oil | No effect [28] | |||

| 7 | Resolution of nasal eosinophilia/rat, OVA then tocopherol then Ozone | γT (100 mg/kg rat × 4 days) | tocopherol-stripped corn oil | Beneficial, Ozone-induced nasal inflammation [37] | |||

| 8 | Resolution of lung eosinophilia/rat, OVA then tocopherol & Ozone | γT (100 mg/kg rat × 4 days) | tocopherol-stripped corn oil | Beneficial, resolution of eosinophil inflammation [38] | |||

| 9 | Neutrophil inflammation/mouse, LPS | αT (50 mg/kg mouse × 1 day) | Beneficial, Neutrophil decrease [39] | ||||

| 10 | Neutrophil inflammation/rat, LPS | αT (inhaled 30 µg/rat × 1 day) | Beneficial, Neutrophil decrease [40] | ||||

| 11 | Neutrophil inflammation/rat, LPS | γT (30 mg/kg rat × 4 days) | tocopherol-stripped corn oil | Beneficial, Neutrophil decrease [41] | |||

| 12 | Neutrophil inflammation/rat, IL-1 | αT (inhaled 30 µg/rat × 1 day) | Beneficial, Neutrophil decrease [42] | ||||

| 13 | Neutrophil inflammation/rat, OVA | γT (100 mg/ kg rat × 2 days before OVA and 2 days after OVA) | tocopherol-stripped corn oil | Beneficial, Neutrophil decrease [43] | |||

| 14 | Neutrophil inflammation/sheep, burn & smoke | γT and αT (inhaled 1220 mg γT + 182 mg αT in 48 h) | γT in flaxseed oil | Beneficial, Neutrophil decrease [44] | |||

| B. Human | |||||||

| Line | Airway Clinical Condition | αT and γT Isoforms in the Studies | Major Outcome [reference] | ||||

| Tocopherol Isoform (Intake or Supplement Dose) | Isoforms (Figure 2) in Reported Oil Vehicle | Plasma Tocopherol [10,45,46,47] | |||||

| Country | αT (μM) | γT (μM) | |||||

| 1 | Asthma/lung function | αT intake (9.9 mg/day) | Italy | 24 | 1.2 | Beneficial [47,48] | |

| 2 | Asthma/lung function | αT intake (6.7 mg/day) | Finland | 24 or 41 | 0.5 or 1.8 | Beneficial [48,49] | |

| 3 | Asthma/lung function | αT intake (17.9 mg/day) | Netherlands | 25 | 2.3 | No effect [48] | |

| 4 | Asthma | αT intake (3.3 to 17.1 or 209.8 mg/day) | USA | 22 or 27 | 5 or 7 | No effect [50] | |

| 5 | Asthma | αT intake (1.1 to 15.7 mg/day) | UK | 24 or 27 | 1.9 or 2.0 | No effect [51] | |

| 6 | Asthma/lung function | αT supplement (500 mg/day × 6 weeks) | γT in soy oil | UK | 24 or 27 | 1.9 or 2.0 | No effect [52] |

| 7 | Asthma | αT-acetate supplement (1000 mg/day × 16 weeks) | USA | 22 or 27 | 5 or 7 | Beneficial [53] | |

| 8 | Asthma | αT supplement (500 mg/day) +Vitamin C supplement (2000 mg/day) × 12 weeks | USA | 22 or 27 | 5 or 7 | No effect [29] | |

| 9 | Ozone/Asthma | Unknown isoforms in tocopherol supplement (50 mg/day) + Vitamin C (250 mg/day) × 12 weeks | Mexico | 23 or 28 | 2.2 or 2.7 | Beneficial [27] | |

| 10 | Endotoxin (LPS)-induced neutrophil airway inflammation | isoform mixture in supplement (50 mg αT, 250 mg βT and δT, 540 mg γT)/day × 7 days | αT in sunflower oil | USA | 22 or 27 | 5 or 7 | Beneficial [41] |

4. Tocopherol Isoforms and Their Clinical Relevance

5. Conclusions

Abbreviations

| CEHC | carboxyethyl-hydroxychroman |

| FEV1 | forced expiratory volume in one second |

| ICAM-1 | intercellular adhesion molecule-1 |

| OVA | chicken egg ovalbumin |

| PKCα | protein kinase Cα |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| VCAM-1 | vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 |

| αTTP | α-tocopherol transfer protein |

| VCAM-1 | vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 |

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bousquet, J.; Bousquet, P.J.; Godard, P.; Daures, J.P. The public health implications of asthma. Bull. World Health Org. 2005, 83, 548–554. [Google Scholar]

- Riccioni, G.; Barbara, M.; Bucciarelli, T.; di Ilio, C.; D’Orazio, N. Antioxidant vitamin supplementation in asthma. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2007, 37, 96–101. [Google Scholar]

- Mannino, D.M.; Homa, D.M.; Akinbami, L.J.; Moorman, J.E.; Gwynn, C.; Redd, S.C. Surveillance for asthma—United States, 1980–1999. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2002, 51, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- McCary, C.A.; Abdala-Valencia, H.; Berdnikovs, S.; Cook-Mills, J.M. Supplemental and highly elevated tocopherol doses differentially regulate allergic inflammation: Reversibility of α-tocopherol and γ-tocopherol’s effects. J. Immunol. 2011, 186, 3674–3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdnikovs, S.; Abdala-Valencia, H.; McCary, C.; Somand, M.; Cole, R.; Garcia, A.; Bryce, P.; Cook-Mills, J.M. Isoforms of vitamin E have opposing immunoregulatory funcitons during inflammation by regulating leukocyte recruitment. J. Immunol. 2009, 182, 4395–4405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook-Mills, J.M.; McCary, C.A. Isoforms of vitamin E differentially regulate inflammation. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 2010, 10, 348–366. [Google Scholar]

- McCary, C.A.; Yoon, Y.; Panagabko, C.; Cho, W.; Atkinson, J.; Cook-Mills, J.M. Vitamin E isoforms directly bind PKCalpha and differentially regulate activation of PKCalpha. Biochem. J. 2012, 441, 189–198. [Google Scholar]

- Cook-Mills, J.M. Eosinophil-Endothelial Cell Interactions. Eosinophils in Health and Disease. In Eosinophils in Health and Disease; Lee, J.J., Rosenberg, H.F., Eds.; Elsevier: Waltham, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 139–153. [Google Scholar]

- Cook-Mills, J.M.; Marchese, M.E.; Abdala-Valencia, H. Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 expression and signaling during disease: Regulation by reactive oxygen species and antioxidants. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011, 15, 1607–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook-Mills, J.M.; Abdala-Valencia, H.; Hartert, T. Two faces of vitamin E in the lung. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 188, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingg, J.M.; Azzi, A. Non-antioxidant activities of vitamin E. Curr. Med. Chem. 2004, 11, 1113–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigelius-Flohe, R.; Traber, M.G. Vitamin E: Function and metabolism. FASEB J. 1999, 13, 1145–1155. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Q.; Christen, S.; Shigenaga, M.K.; Ames, B.N. Gamma-tocopherol, the major form of vitamin E in the US diet, deserves more attention. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 74, 714–722. [Google Scholar]

- Grammas, P.; Hamdheydari, L.; Benaksas, E.J.; Mou, S.; Pye, Q.N.; Wechter, W.J.; Floyd, R.A.; Stewart, C.; Hensley, K. Anti-inflammatory effects of tocopherol metabolites. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 319, 1047–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, G. How an increased intake of α-tocopherol can suppress the bioavailability of γ-tocopherol. Nutr. Rev. 2006, 64, 295–299. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Y.; Vasu, V.T.; Valacchi, G.; Leonard, S.; Aung, H.H.; Schock, B.C.; Kenyon, N.J.; Li., C.S.; Traber, M.G.; Cross, C.E. Severe vitamin E deficiency modulates airway allergic inflammatory responses in the murine asthma model. Free Radic. Res. 2008, 42, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, Y.; Saito, Y.; Jones, L.S.; Shigeri, Y. Chemical reactivities and physical effects in comparison between tocopherols and tocotrienols: Physiological significance and prospects as antioxidants. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2007, 104, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, J.; Epand, R.F.; Epand, R.M. Tocopherols and tocotrienols in membranes: A critical review. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 44, 739–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; May, J.M. Ascorbic acid spares α-tocopherol and prevents lipid peroxidation in cultured H4IIE liver cells. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2003, 247, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpner, A.D.; Handelman, G.J.; Harris, J.M.; Belmont, C.A.; Blumberg, J.B. Protection by vitamin C of loss of vitamin E in cultured rat hepatocytes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1998, 359, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buettner, G.R. The pecking order of free radicals and antioxidants: Lipid peroxidation, α-tocopherol, and ascorbate. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1993, 300, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.C.; Zhu, B.Z.; Frei, B. Potential antiatherogenic mechanisms of ascorbate (vitamin C) and α-tocopherol (vitamin E). Circ. Res. 2000, 87, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christen, S.; Woodall, A.A.; Shigenaga, M.K.; Southwell-Keely, P.T.; Duncan, M.W.; Ames, B.N. γ-Tocopherol traps mutagenic electrophiles such as NO(X) and complements α-tocopherol: Physiological implications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 3217–3222. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, A.; Liebner, F.; Netscher, T.; Mereiter, K.; Rosenau, T. Vitamin E chemistry. Nitration of non-α-tocopherols: Products and mechanistic considerations. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 6504–6512. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, G. γ-Tocopherol: An efficient protector of lipids against nitric oxide-initiated peroxidative damage. Nutr. Rev. 1997, 55, 376–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, C.S.; Young, M. Enzymatic formation of ascorbic acid in liver homogenate of mice fed dietary ascorbic acid. In Vivo 1990, 4, 167–169. [Google Scholar]

- Sienra-Monge, J.J.; Ramirez-Aguilar, M.; Moreno-Macias, H.; Reyes-Ruiz, N.I.; del Rio-Navarro, B.E.; Ruiz-Navarro, M.X.; Hatch, G.; Crissman, K.; Slade, R.; Devlin, R.B.; et al. Antioxidant supplementation and nasal inflammatory responses among young asthmatics exposed to high levels of ozone. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2004, 138, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchankova, J.; Voprsalova, M.; Kottova, M.; Semecky, V.; Visnovsky, P. Effects of oral α-tocopherol on lung response in rat model of allergic asthma. Respirology 2006, 11, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, M.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, B.; Robinette, C.; Crissman, K.; Hatch, G.; Alexis, N.E.; Peden, D. Combination treatment with high-dose vitamin C and alpha-tocopherol does not enhance respiratory-tract lining fluid vitamin C levels in asthmatics. Inhal. Toxicol. 2009, 21, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, I.; de Serna, D.G.; Gutierrez, A.; Schade, D.S. Vitamin E in humans: An explanation of clinical trial failure. Endocr. Pract. 2006, 12, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzi, A.; Stocker, A. Vitamin E: Non-antioxidant roles. Prog. Lipid Res. 2000, 39, 231–255. [Google Scholar]

- Allan, K.; Devereux, G. Diet and asthma: Nutrition implications from prevention to treatment. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2011, 111, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shvedova, A.A.; Kisin, E.R.; Kagan, V.E.; Karol, M.H. Increased lipid peroxidation and decreased antioxidants in lungs of guinea pigs following an allergic pulmonary response. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1995, 132, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, N.; Murata, T.; Tamai, H.; Tanaka, H.; Nagai, H. Effects of alpha tocopherol and probucol supplements on allergen-induced airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness in a mouse model of allergic asthma. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2006, 141, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabalirajan, U.; Aich, J.; Leishangthem, G.D.; Sharma, S.K.; Dinda, A.K.; Ghosh, B. Effects of vitamin E on mitochondrial dysfunction and asthma features in an experimental allergic murine model. J. Appl. Physiol. 2009, 107, 1285–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdala-Valencia, H.; Berdnikovs, S.; Cook-Mills, J.M. Vitamin E isoforms differentially regulate intercellular adhesion molecule-1 activation of PKCα in human microvascular endothelial cells. PLoS One 2012, 7, e41054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdala-Valencia, H.; Earwood, J.; Bansal, S.; Jansen, M.; Babcock, G.; Garvy, B.; Wills-Karp, M.; Cook-Mills, J.M. Nonhematopoietic NADPH oxidase regulation of lung eosinophilia and airway hyperresponsiveness in experimentally induced asthma. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2007, 292, L1111–L1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavan, P.; Deem, T.L.; Schwemberger, S.J.; Babcock, G.F.; Cook-Mills, J.M.; Zucker, S.D. Unconjugated bilirubin inhibits VCAM-1-mediated transendothelial leukocyte migration. J. Immunol. 2005, 174, 3709–3718. [Google Scholar]

- Pero, R.S.; Borchers, M.T.; Spicher, K.; Ochkur, S.I.; Sikora, L.; Rao, S.P.; Abdala-Valencia, H.; O’Neill, K.R.; Shen, H.; McGarry, M.P.; et al. Galphai2-mediated signaling events in the endothelium are involved in controlling leukocyte extravasation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 4371–4376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saremi, A.; Arora, R. Vitamin E and cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Ther. 2010, 17, e56–e65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppala, J.M.; Virtamo, J.; Fogelholm, R.; Huttunen, J.K.; Albanes, D.; Taylor, P.R.; Heinonen, O.P. Controlled trial of α-tocopherol and β-carotene supplements on stroke incidence and mortality in male smokers. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2000, 20, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.R., III; Pastor-Barriuso, R.; Dalal, D.; Riemersma, R.A.; Appel, L.J.; Guallar, E. Meta-analysis: High-dosage vitamin E supplementation may increase all-cause mortality. Ann. Intern. Med. 2005, 142, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinonen, O.P.; Albanes, D.; The α-Tocopherol, β Carotene Cancer Prevention Study Group. The effect of vitamin E and β carotene on the incidence of lung cancer and other cancers in male smokers. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994, 330, 1029–1035. [Google Scholar]

- Tornwall, M.E.; Virtamo, J.; Korhonenm, P.A.; Virtanen, M.J.; Albanes, D.; Huttunen, J.K. Postintervention effect of α tocopherol and β carotene on different strokes: A 6-year follow-up of the α Tocopherol, β Carotene Cancer Prevention Study. Stroke 2004, 35, 1908–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzi, A.; Brigelius-Flohe, R.; Kelly, F.; Lodge, J.K.; Ozer, N.; Packer, L.; Sies, H. On the opinion of the European Commission “Scientific Committee on Food” regarding the tolerable upper intake level of vitamin E (2003). Eur. J. Nutr. 2005, 44, 60–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abner, E.L.; Schmitt, F.A.; Mendiondo, M.S.; Marcum, J.L.; Kryscio, R.J. Vitamin E and all-cause mortality: A meta-analysis. Curr. Aging Sci. 2011, 4, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, K.H.; Kamal-Eldin, A.; Elmadfa, I. Gamma-tocopherol—An underestimated vitamin? Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2004, 48, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Franchi, L.; Nunez, G. The protein kinase PKR is critical for LPS-induced iNOS production but dispensable for inflammasome activation in macrophages. Eur. J. Immunol. 2013, 43, 1147–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhrzadeh, L.; Laskin, J.D.; Laskin, D.L. Ozone-induced production of nitric oxide and TNF-α and tissue injury are dependent on NF-kappaB p50. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2004, 287, L279–L285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J.G.; Jiang, Q.; Harkema, J.R.; Illek, B.; Patel, D.D.; Ames, B.N.; Peden, D.B. Ozone enhancement of lower airway allergic inflammation is prevented by γ-tocopherol. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2007, 43, 1176–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J.G.; Harkema, J.R.; Jiang, Q.; Illek, B.; Ames, B.N.; Peden, D.B. γ-Tocopherol attenuates ozone-induced exacerbation of allergic rhinosinusitis in rats. Toxicol. Pathol. 2009, 37, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J.G.; Jiang, Q.; Harkema, J.R.; Ames, B.N.; Illek, B.; Roubey, R.A.; Peden, D.B. γ-Tocopherol prevents airway eosinophilia and mucous cell hyperplasia in experimentally induced allergic rhinitis and asthma. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2008, 38, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hybertson, B.M.; Chung, J.H.; Fini, M.A.; Lee, Y.M.; Allard, J.D.; Hansen, B.N.; Cho, O.J.; Shibao, G.N.; Repine, J.E. Aerosol-administered α-tocopherol attenuates lung inflammation in rats given lipopolysaccharide intratracheally. Exp. Lung Res. 2005, 31, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hybertson, B.M.; Leff, J.A.; Beehler, C.J.; Barry, P.C.; Repine, J.E. Effect of vitamin E deficiency and supercritical fluid aerosolized vitamin E supplementation on interleukin-1-induced oxidative lung injury in rats. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1995, 18, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocksen, D.; Ekstrand-Hammarstrom, B.; Johansson, L.; Bucht, A. Vitamin E reduces transendothelial migration of neutrophils and prevents lung injury in endotoxin-induced airway inflammation. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2003, 28, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, K.; Ikeda, S.; Obayashi, M. Comparative effects of flaxseed and sesame seed on vitamin E and cholesterol levels in rats. Lipids 2003, 38, 1249–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamahata, A.; Enkhbaatar, P.; Kraft, E.R.; Lange, M.; Leonard, S.W.; Traber, M.G.; Cox, R.A.; Schmalstieg, F.C.; Hawkins, H.K.; Whorton, E.B.; et al. γ-Tocopherol nebulization by a lipid aerosolization device improves pulmonary function in sheep with burn and smoke inhalation injury. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 45, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, M.L.; Wagner, J.G.; Kala, A.; Mills, K.; Wells, H.B.; Alexis, N.E.; Lay, J.C.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, H.; et al. Vitamin E, γ-tocopherol, reduces airway neutrophil recruitment after inhaled endotoxin challenge in rats and in healthy volunteers. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 60, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdala-Valencia, H.; Cook-Mills, J.M. VCAM-1 signals activate endothelial cell protein kinase Cα via oxidation. J. Immunol. 2006, 177, 6379–6387. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney, C.W.; Azzi, A. Vitamin E inhibits protein kinase C activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1988, 154, 694–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, F.J.; Mudway, I.; Blomberg, A.; Frew, A.; Sandstrom, T. Altered lung antioxidant status in patients with mild asthma. Lancet 1999, 354, 482–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalayci, O.; Besler, T.; Kilinc, K.; Sekerel, B.E.; Saraclar, Y. Serum levels of antioxidant vitamins (α tocopherol, β carotene, and ascorbic acid) in children with bronchial asthm. Turk. J. Pediatr. 2000, 42, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sohemy, A.; Baylin, A.; Ascherio, A.; Kabagambe, E.; Spiegelman, D.; Campos, H. Population-based study of α- and γ-tocopherol in plasma and adipose tissue as biomarkers of intake in Costa Rican adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 74, 356–363. [Google Scholar]

- Retana-Ugalde, R.; Vargas, L.A.; Altamirano-Lozano, M.; Mendoza-Nunez, V.M. Influence of the placebo effect on oxidative stress in healthy older adults of Mexico City. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2009, 34, 665–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, G.; Galvan, M. Relation of total cholesterol in serum tocopherols, probabilistic study in Mexican children. Arch. Latinoam. Nutr. 2011, 61, 127–134. [Google Scholar]

- Devereux, G.; Seaton, A. Diet as a risk factor for atopy and asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2005, 115, 1109–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieri, J.G.; Evarts, R.P. Tocopherols and fatty acids in American diets. The recommended allowance for vitamin E. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1973, 62, 147–151. [Google Scholar]

- Bieri, J.G.; Evarts, R.P. Vitamin E adequacy of vegetable oils. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1975, 66, 134–139. [Google Scholar]

- Meydani, S.N.; Shapiro, A.C.; Meydani, M.; Macauley, J.B.; Blumberg, J.B. Effect of age and dietary fat (fish, corn and coconut oils) on tocopherol status of C57BL/6Nia mice. Lipids 1987, 22, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Moreno, C.; Dorfman, S.E.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Martin, A. Dietary fat type affects vitamins C and E and biomarkers of oxidative status in peripheral and brain tissues of golden Syrian hamsters. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 655–660. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, S.T. Diet as a risk factor for asthma. Ciba Found. Symp. 1997, 206, 244–257. [Google Scholar]

- Troisi, R.J.; Willett, W.C.; Weiss, S.T.; Trichopoulos, D.; Rosner, B.; Speizer, F.E. A prospective study of diet and adult-onset asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1995, 151, 1401–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dow, L.; Tracey, M.; Villar, A.; Coggon, D.; Margetts, B.M.; Campbell, M.J.; Holgate, S.T. Does dietary intake of vitamins C and E influence lung function in older people? Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1996, 154, 1401–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, H.A.; Grievink, L.; Tabak, C. Dietary influences on chronic obstructive lung disease and asthma: A review of the epidemiological evidence. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 1999, 58, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabak, C.; Smit, H.A.; Rasanen, L.; Fidanza, F.; Menotti, A.; Nissinen, A.; Feskens, E.J.; Heederik, D.; Kromhout, D. Dietary factors and pulmonary function: A cross sectional study in middle aged men from three European countries. Thorax 1999, 54, 1021–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.; Britton, J.R.; Leonardi-Bee, J.A. Association between antioxidant vitamins and asthma outcome measures: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax 2009, 64, 610–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoskins, A.; Roberts, J.L., II; Milne, G.; Choi, L.; Dworski, R. Natural-source d-α-tocopheryl acetate inhibits oxidant stress and modulates atopic asthma in humans in vivo. Allergy 2012, 67, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devereux, G. Early life events in asthma—Diet. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2007, 42, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martindale, S.; McNeill, G.; Devereux, G.; Campbell, D.; Russell, G.; Seaton, A. Antioxidant intake in pregnancy in relation to wheeze and eczema in the first two years of life. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2005, 171, 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, P.J.; Lewis, S.A.; Britton, J.; Fogarty, A. Vitamin E supplements in asthma: A parallel group randomised placebo controlled trial. Thorax 2004, 59, 652–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiser, M.; Lay, J.C.; Bennett, W.D.; Zhou, H.; Wang, X.; Peden, D.B.; Alexis, N.E. Effects of ex vivo γ-tocopherol on airway macrophage function in healthy and mild allergic asthmatics. J. Innate Immun. 2013, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misso, N.L.; Brooks-Wildhaber, J.; Ray, S.; Vally, H.; Thompson, P.J. Plasma concentrations of dietary and nondietary antioxidants are low in severe asthma. Eur. Respir. J. 2005, 26, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunemann, H.J.; Grant, B.J.; Freudenheim, J.L.; Muti, P.; Browne, R.W.; Drake, J.A.; Klocke, R.A.; Trevisan, M. The relation of serum levels of antioxidant vitamins C and E, retinol and carotenoids with pulmonary function in the general population. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2001, 163, 1246–1255. [Google Scholar]

- Gazdik, F.; Gvozdjakova, A.; Nadvornikova, R.; Repicka, L.; Jahnova, E.; Kucharská, J.; Piják, M.R.; Gazdíková, K. Decreased levels of coenzyme Q10 in patients with bronchial asthma. Allergy 2002, 57, 811–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, J.M.; de Roos, A.J.; Renner, J.B.; Luta, G.; Cohen, A.; Craft, N.; Helmick, C.G.; Hochberg, M.C.; Arab, L. A case-control study of serum tocopherol levels and the α- to γ-tocopherol ratio in radiographic knee osteoarthritis: The Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2004, 159, 968–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, M.; Traber, M.G.; Jacques, P.F.; Cross, C.E.; Hu, Y.; Block, G. Does γ-tocopherol play a role in the primary prevention of heart disease and cancer? A review. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2006, 25, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, A.; Zingg, J.M. Cellular, molecular and clinical aspects of vitamin E on atherosclerosis prevention. Mol. Aspects Med. 2007, 28, 538–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siekmeier, R.; Steffen, C.; Marz, W. Role of oxidants and antioxidants in atherosclerosis: Results of in vitro and in vivo investigations. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007, 12, 265–282. [Google Scholar]

- Meydani, M. Vitamin E modulation of cardiovascular disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2004, 1031, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, A.; Dutta, S.K. Vitamin E and its role in the prevention of atherosclerosis and carcinogenesis: A review. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2003, 22, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Abdala-Valencia, H.; Berdnikovs, S.; Cook-Mills, J.M. Vitamin E Isoforms as Modulators of Lung Inflammation. Nutrients 2013, 5, 4347-4363. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu5114347

Abdala-Valencia H, Berdnikovs S, Cook-Mills JM. Vitamin E Isoforms as Modulators of Lung Inflammation. Nutrients. 2013; 5(11):4347-4363. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu5114347

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdala-Valencia, Hiam, Sergejs Berdnikovs, and Joan M. Cook-Mills. 2013. "Vitamin E Isoforms as Modulators of Lung Inflammation" Nutrients 5, no. 11: 4347-4363. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu5114347

APA StyleAbdala-Valencia, H., Berdnikovs, S., & Cook-Mills, J. M. (2013). Vitamin E Isoforms as Modulators of Lung Inflammation. Nutrients, 5(11), 4347-4363. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu5114347