1. Introduction

Religious beliefs and practices are among the most salient person-level determinants of health behaviors worldwide [

1]. Religiosity and religious affiliation can shape norms related to self-regulation, social support, and health responsibility, while also embedding individuals in communities that transmit dietary expectations, fasting traditions, and food taboos [

2]. Evidence linking religiosity to diet quality and weight-related behaviors is mixed across contexts, and appears to vary by the specific religious tradition, the dimension of religiosity assessed, and the outcome under study. Importantly, much of the existing evidence is correlational in nature, limiting causal inferences regarding the direction or mechanisms of these associations. Moreover, prior research has rarely examined how religious influences on nutrition attitudes operate alongside modifiable digital competencies, leaving an important gap in understanding the joint role of values and information-processing skills [

3]. In adult majority-Muslim settings, where religious identity is widely shared yet heterogeneously practiced, examining religiosity and affiliation together with modifiable psychological skills may help clarify variability in positive nutrition attitudes—that is, favorable orientations toward adopting healthy eating behaviors [

4].

Positive nutrition attitudes refer to favorable orientations toward adopting and maintaining healthy eating behaviors, including intentions to consume nutritious foods, attention to balanced dietary practices, and receptiveness to evidence-based dietary guidance [

5]. One such modifiable skill is e-nutrition literacy, a nutrition-specific extension of e-health literacy, defined as the ability to find, appraise, and apply nutrition information encountered in digital environments [

6]. As nutrition information ecosystems have migrated to social media and influencer-driven channels, higher e-nutrition literacy may buffer against misinformation, support evidence-seeking, and facilitate favorable attitudes toward dietary guidance [

7]. In this respect, e-nutrition literacy represents a potentially critical mechanism through which individuals translate abstract health values into concrete nutrition attitudes. In religious contexts, stronger e-nutrition literacy may further enable individuals to critically evaluate nutrition messages encountered through faith-based networks or religiously framed online content, thereby amplifying value-consistent health behaviors while filtering misleading claims, particularly among those embedded in religious affiliations. Conversely, limited e-nutrition literacy can heighten susceptibility to sensational claims, potentially undermining trust in professional advice and weakening attitudes toward prudent nutrition practices [

8]. Prior research has shown that higher e-healthy diet/e-nutrition literacy is associated with healthier eating behaviours and related health outcomes in non-Muslim-majority settings, supporting its role as a central predictor in our model [

9]. However, whether this association is strengthened, weakened, or reshaped by religiosity or religious affiliation remains largely unexplored, particularly in adult majority-Muslim populations [

10]. Addressing this gap is essential to disentangle whether positive nutrition attitudes arise primarily from digital information skills, from value-based motivations, or from their interaction within specific cultural milieus [

11].

Türkiye provides a timely and informative setting for this inquiry. Rapid digitalization has expanded access to nutrition content, while food price volatility and positive healthy nutrition debates keep diet choices salient in daily life [

12]. At the same time, the population is predominantly Muslim, yet marked by diverse patterns of religious practice and identity. In such a setting, digital literacy may either reinforce religiously grounded dietary motivations through credible information or exacerbate confusion when misinformation circulates within value-laden contexts. Thus, Türkiye offers a natural context to examine threshold and interaction effects between religiosity, affiliation, and e-nutrition literacy on nutrition attitudes. Mapping how religiosity and affiliation relate to attitudes when e-nutrition literacy is high versus low can reveal leverage points for interventions that respect religious values while upgrading information-navigation skills [

13]. More broadly, insights into how digital nutrition literacy interacts with value-based motivations may be transferable to other cultural or religious contexts where beliefs, norms, and social frameworks shape nutrition attitudes. In such settings, integrating information-navigation skills with culturally or faith-informed perspectives may support the development of more contextually responsive nutrition interventions. This integrative perspective—examining religiosity, affiliation, and e-nutrition literacy simultaneously through both classical regression and machine learning approaches—represents a key novelty of the present study.

Accordingly, the primary objective of the current study was to examine both the independent and interactive associations of religiosity, religious affiliation, and e-nutrition literacy with positive nutrition attitudes among adults in Türkiye. Specifically, we tested three hypotheses. First, we hypothesized that higher e-nutrition literacy would be positively associated with positive nutrition attitudes (H1). Second, we hypothesized that religiosity would demonstrate an independent positive association with nutrition attitudes, net of digital literacy skills (H2). Third, we hypothesized that e-nutrition literacy would moderate the associations of religiosity and religious affiliation with nutrition attitudes (H3). By explicitly considering these interaction mechanisms through both traditional regression and machine learning approaches (Random Forest with SHAP interpretation), the study aims to clarify whether interventions should prioritize enhancing e-nutrition literacy, engaging religiously grounded motivations, or strategically combining both approaches to foster durable, positive nutrition attitudes in an adult majority-Muslim context.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

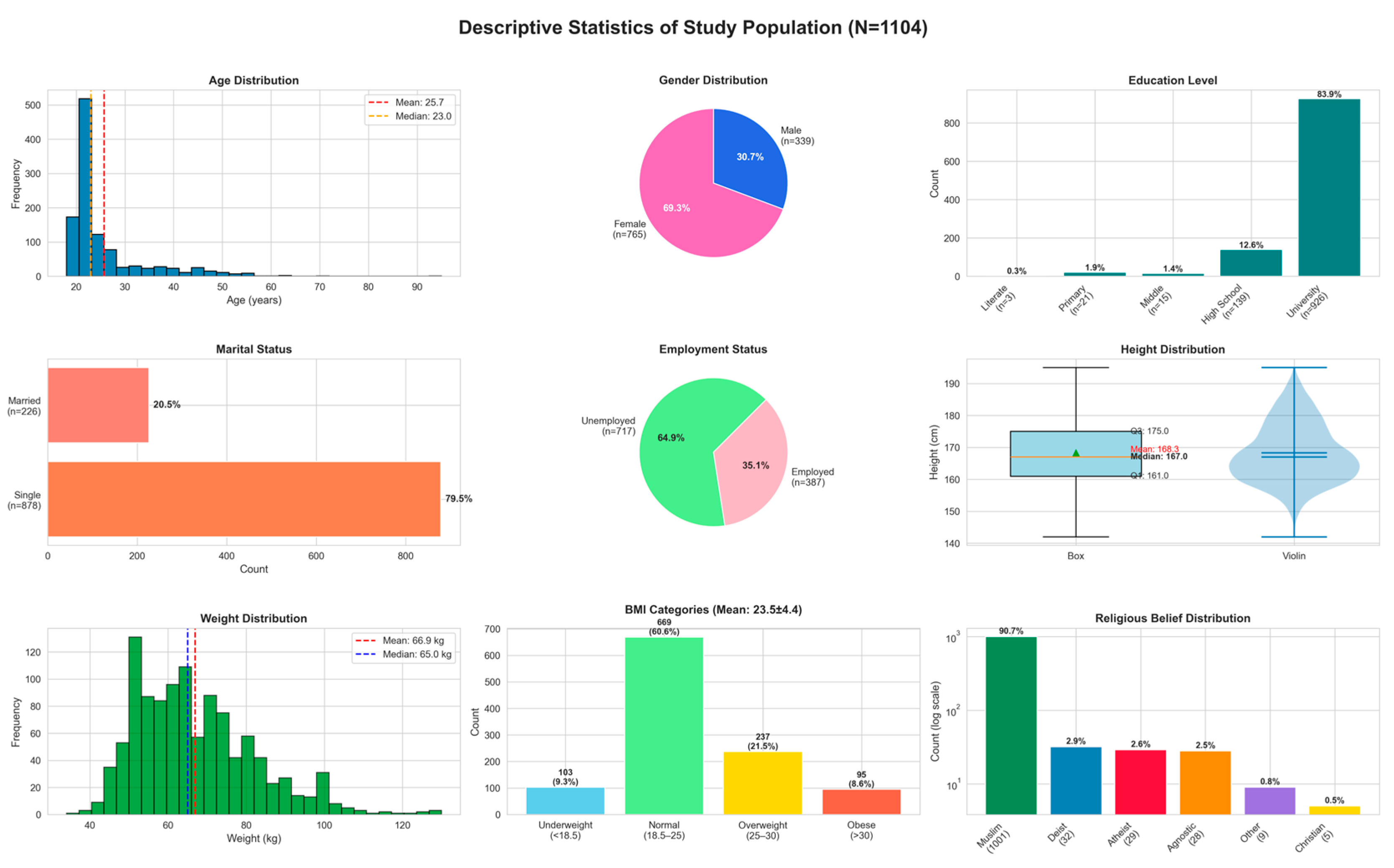

The study included 1104 participants with a mean age of 25.7 ± 8.4 years (median: 23.0, Q1–Q3: 21.0–26.0; range: 18–95). The average height was 168.3 ± 9.2 cm (median: 167.0, Q1–Q3: 161.0–175.0; range: 142–195), mean weight 66.9 ± 15.4 kg (median: 65.0, Q1–Q3: 55.0–75.2; range: 34–130), and mean BMI 23.5 ± 4.4 kg/m

2 (median: 22.8, Q1–Q3: 20.3–25.8; range: 14.4–45.7). Based on BMI categories, 9.3% were underweight, 60.6% were within the normal range, 21.5% overweight, and 8.6% obese (

Figure 1); however, subsequent analyses were conducted using BMI as a continuous variable to capture more detailed variation.

In terms of sociodemographic characteristics, the majority of participants were female (69.3%, n = 765) and single (79.5%, n = 878). Employment status indicated that 64.9% (n = 717) were unemployed. Regarding education, most had a university degree (n = 926, 83.9%), followed by high school graduates (n = 139, 12.6%) and a smaller group with middle school or below (n = 39, 3.5%) (

Figure 1).

Descriptive scores for key study variables were as follows: the total religiosity score averaged 16.4 ± 5.1 (range 5–27), positive nutrition attitude averaged 17.2 ± 5.0 (range 5–25), and electronic nutrition literacy averaged 29.9 ± 6.5 (range 15–51). Tests of distributional properties indicated that religiosity (skew = −0.16, kurtosis = −0.52), positive nutrition attitudes (skew = −0.55, kurtosis = −0.26), and e-nutrition literacy (skew = 0.28, kurtosis = −0.24) all demonstrated near-normal distributions. Therefore, no additional transformation of these variables was deemed necessary.

For analysis, these were categorized as University, High School, and Middle or below. With respect to religious belief, 90.7% (n = 1001) identified as Muslim, while 9.3% (n = 103) were classified as Non-Muslim by combining smaller categories (deist, atheist, agnostic, Christian, and other).

3.2. Linear Regression Analysis

E-nutrition literacy was the strongest predictor (

β = 0.155, 95% CI: 0.10–0.21,

p < 0.001), and high school graduates scored lower than university graduates (

β = −1.126, 95% CI: −2.17 to −0.08,

p = 0.034). In contrast, religiosity (

β = 0.031,

p = 0.413), religious affiliation (

β = 0.014,

p = 0.983), age (

β = 0.038,

p = 0.244), and BMI (

β = 0.002,

p = 0.955) were not significantly associated with nutrition attitudes. Full coefficient estimates with 95% confidence intervals are provided in the

Supplementary Material.

Diagnostic checks identified heteroskedasticity (Breusch–Pagan

p < 0.05) and non-normal residuals (Anderson–Darling statistic = 6.79, exceeding the 1% critical value), as well as a subset of observations exceeding Cook’s D (6%) and leverage thresholds (7%). Accordingly, HC1 robust standard errors were applied, and substantive conclusions for key predictors remained unchanged. The limited explanatory power of the linear specification, together with assumption violations, motivated the use of Random Forest models with SHAP analyses to explore potential non-linear effects and interactions (see

Supplementary Material for full statistical output and diagnostics).

3.3. Random Forest and SHAP Analysis

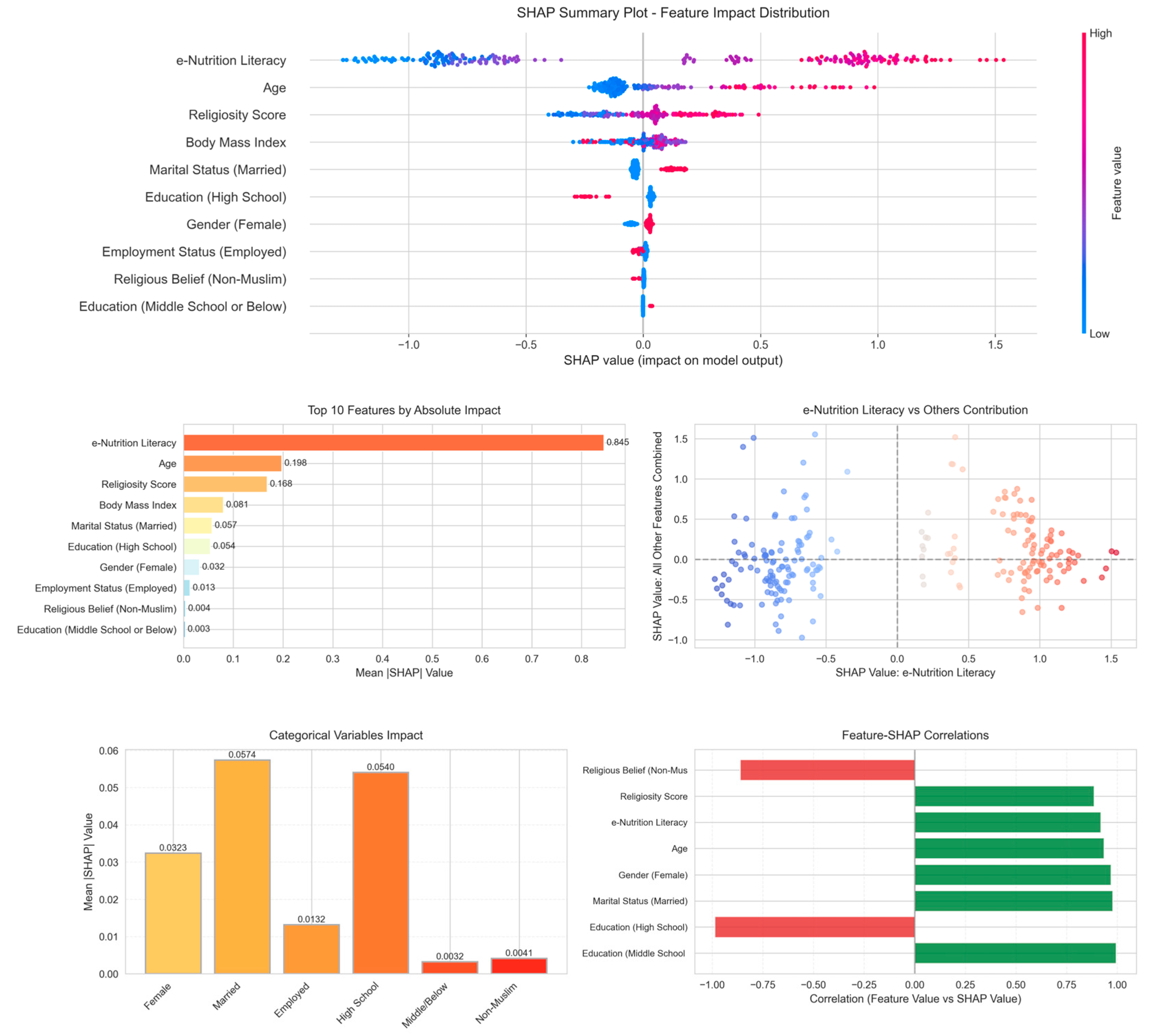

An optimized Random Forest model, tuned through extensive hyperparameter search (150 random combinations with 5-fold cross-validation), achieved only marginal improvement over linear regression (test R2 = 0.064, RMSE = 5.01) while maintaining minimal overfitting (train R2 = 0.098, test R2 = 0.064, OOB score = 0.038). The modest train-test gap (0.034) and the close alignment between OOB and test performance suggest adequate generalization despite the ensemble’s complexity. Feature importance analysis revealed a highly concentrated predictive structure, with e-nutrition literacy accounting for 49.6% of total importance, followed by age (14.6%), religiosity (13.5%), and BMI (13.3%). Permutation importance on the test set confirmed this hierarchy, showing that shuffling e-nutrition literacy led to a substantial performance drop (ΔR2 = 0.088), whereas all other predictors had negligible effects (all ΔR2 < 0.006). The concentration of predictive power in a single variable motivated the use of SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis to examine individual-level heterogeneity, assess how features contribute to single predictions, and identify potential—albeit limited—non-linear patterns across the data.

The analysis revealed that e-nutrition literacy’s contribution varied substantially across individuals (SHAP values: −1.28 to 1.54), though with an unexpected bimodal pattern—only 48.9% of observations showed positive SHAP values despite the feature’s overall positive association. The mean absolute SHAP value for e-nutrition literacy (0.845) was 2.63 times larger than the combined contribution of all other predictors (0.322), confirming its dominant but heterogeneous role. Notably, demographic variables demonstrated minimal predictive utility despite their theoretical importance. Gender showed the highest positive rate (71.0% positive SHAP) among categorical variables but with negligible magnitude (mean |SHAP| = 0.032). Educational categories displayed paradoxical patterns, with high school education showing predominantly positive SHAP values (89.6%) despite negative linear coefficients, suggesting complex interactions not captured by main effects. The feature-SHAP correlations revealed strong monotonic relationships for structural variables (education categories showing correlations > 0.98) but weaker associations for continuous predictors, indicating that the Random Forest model primarily used categorical variables for partitioning rather than prediction (

Figure 2).

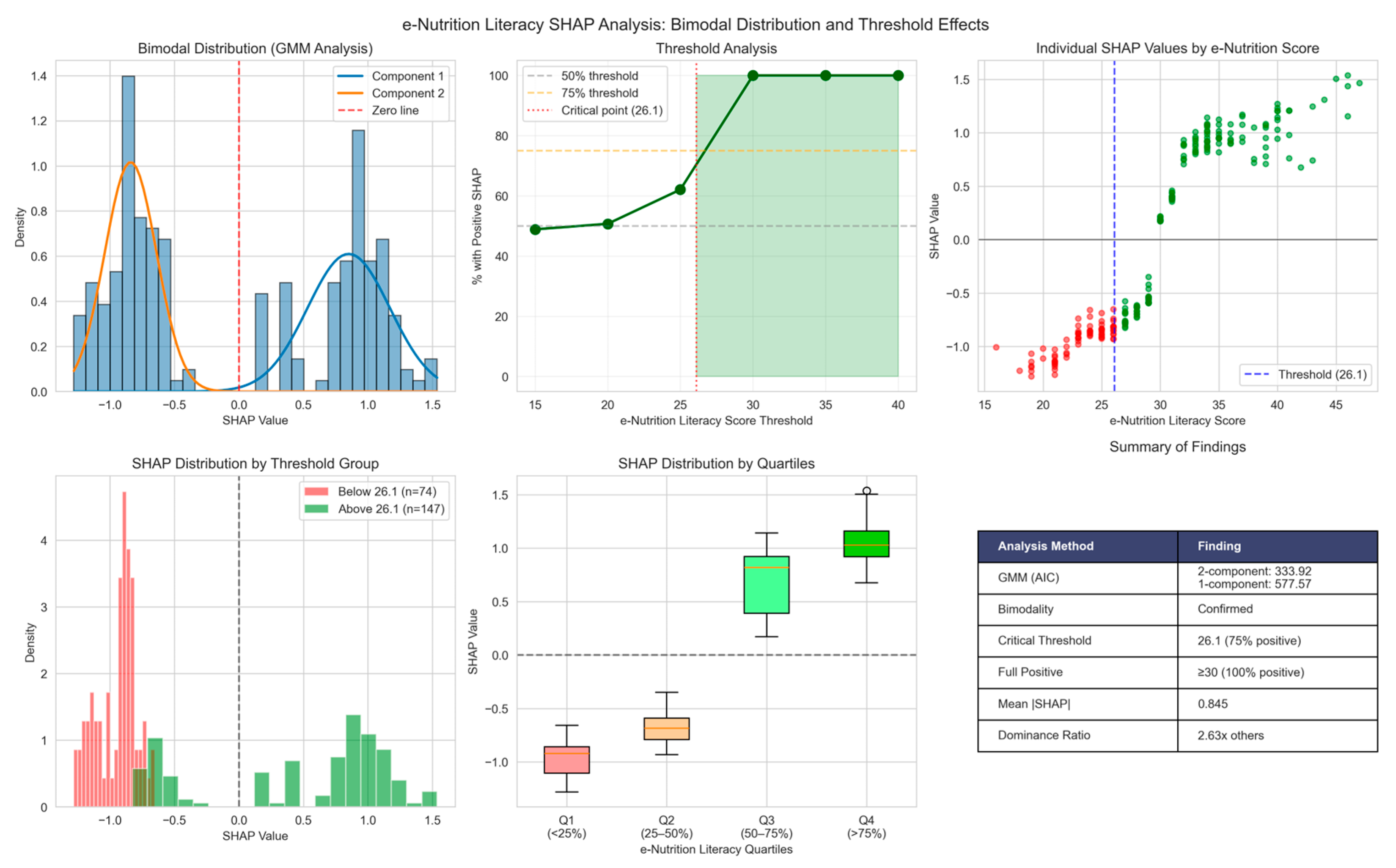

3.4. Threshold Effects

To investigate the distributional properties and threshold effects of e-nutrition literacy’s impact, we performed Gaussian Mixture Modeling and threshold analysis on SHAP values. The analysis revealed that e-nutrition literacy’s contribution followed a bimodal distribution, confirmed through Gaussian Mixture Modeling (2-component GMM: AIC = 333.92 vs. 1-component: AIC = 577.57), with distinct clusters around negative and positive SHAP values.

As noted before, only 48.9% of observations showed positive SHAP values. Threshold analysis revealed critical cut-points at e-nutrition literacy ≥ 26.1 (75% positive SHAP) and ≥30 (100% positive SHAP). These results suggest that e-nutrition literacy operates through a threshold mechanism rather than linear association, with meaningful benefits emerging only above a score of 26 (

Figure 3).

The apparent paradox of high school education showing positive SHAP values (89.6%) was resolved through subgroup analysis: high school graduates actually had lower e-nutrition literacy (28.83 vs. 30.14), older age (30.3 vs. 25.8 years), and negative mean SHAP values (−0.019 vs. 0.006) compared to university graduates, indicating that the tree-based model used education primarily for partitioning rather than direct prediction. This result illustrates an important limitation of tree-based models: variables with high SHAP importance may serve as splitting criteria rather than genuine causal predictors. Education level appears to function as a proxy variable that helps the model partition the feature space to capture complex interactions between age, digital literacy, and nutrition attitudes, rather than directly influencing the outcome. This distinction is crucial for intervention design—improving education levels alone may not enhance nutrition attitudes unless accompanied by improvements in e-nutrition literacy.

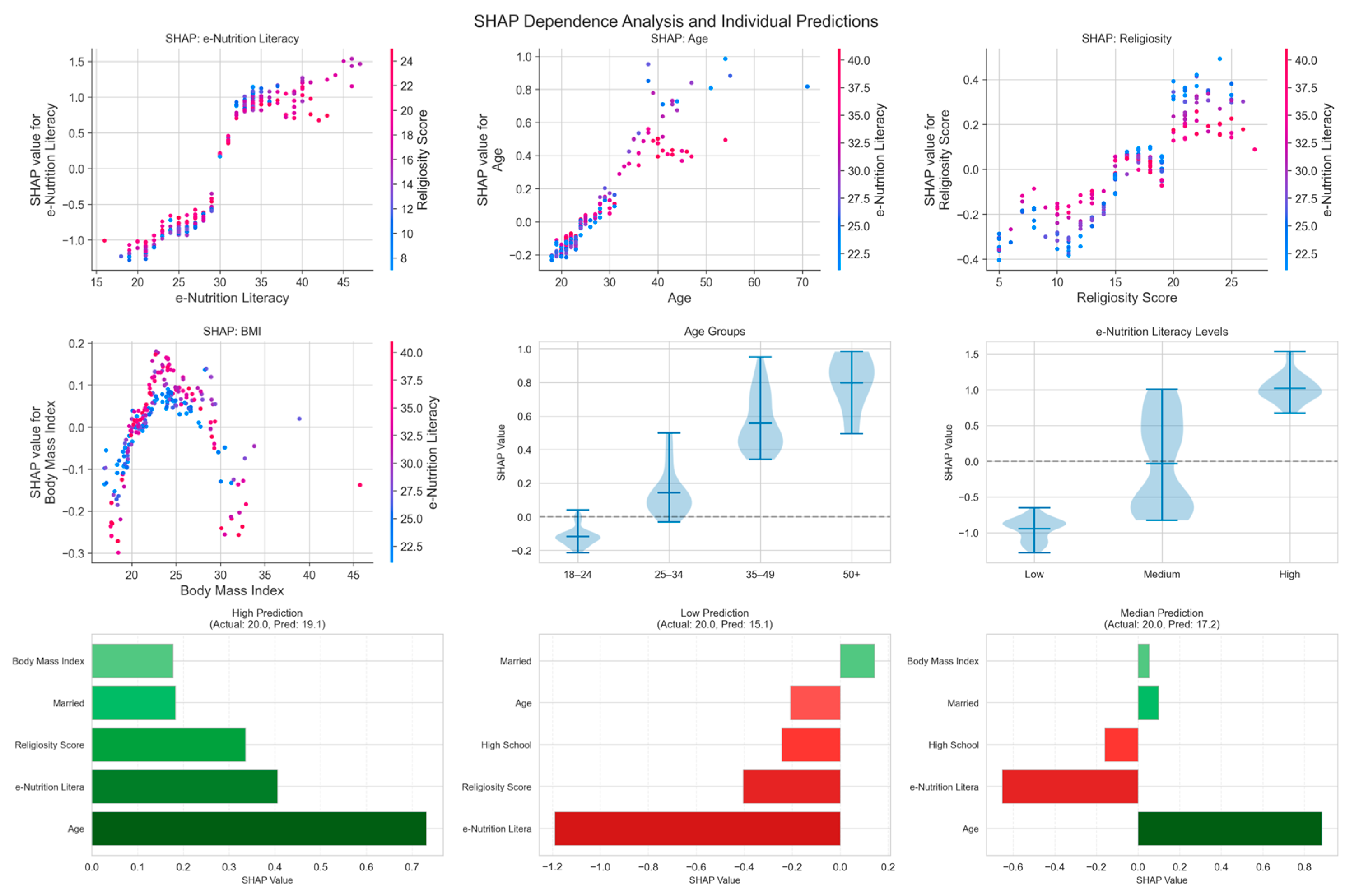

Age demonstrated a clear threshold effect in SHAP values. Younger individuals (under 25 years) had negative SHAP values (mean = −0.127), indicating that being young was associated with lower nutrition attitude scores. In contrast, middle-aged (25–35 years: mean SHAP = 0.098) and particularly older adults showed progressively positive contributions, with those over 50 years having the highest positive impact (mean SHAP = 0.798). This suggests that nutrition awareness and positive attitudes develop with age, possibly due to increased health consciousness, life experience, or health-related concerns that emerge later in life. This non-linear age relationship, which the linear model failed to capture, indicates that nutrition attitudes are influenced by life-stage transitions rather than simply increasing linearly with age. Religiosity and BMI showed mixed effects across individuals. While 54.8% of participants showed positive SHAP values for religiosity and 63.8% for BMI, the remaining participants showed negative values, meaning these variables improved nutrition attitudes for some individuals but worsened them for others. This bidirectional pattern suggests that the relationship between religiosity/BMI and nutrition attitudes depends on unmeasured personal or contextual factors—for instance, religiosity might promote positive nutrition attitudes in some cultural contexts but not others, and BMI’s effect might vary based on individual health awareness or body image concerns (

Figure 4).

In the SHAP analysis of the Random Forest model, the observed bimodal distribution and threshold effects indicated that different dynamics may operate below and above the identified cut-off value of 26.1 for e-nutrition literacy. Based on these results, a detailed regression modeling approach was undertaken to systematically examine the differential effects of religion and religiosity on nutrition attitudes within the low and high e-nutrition literacy groups.

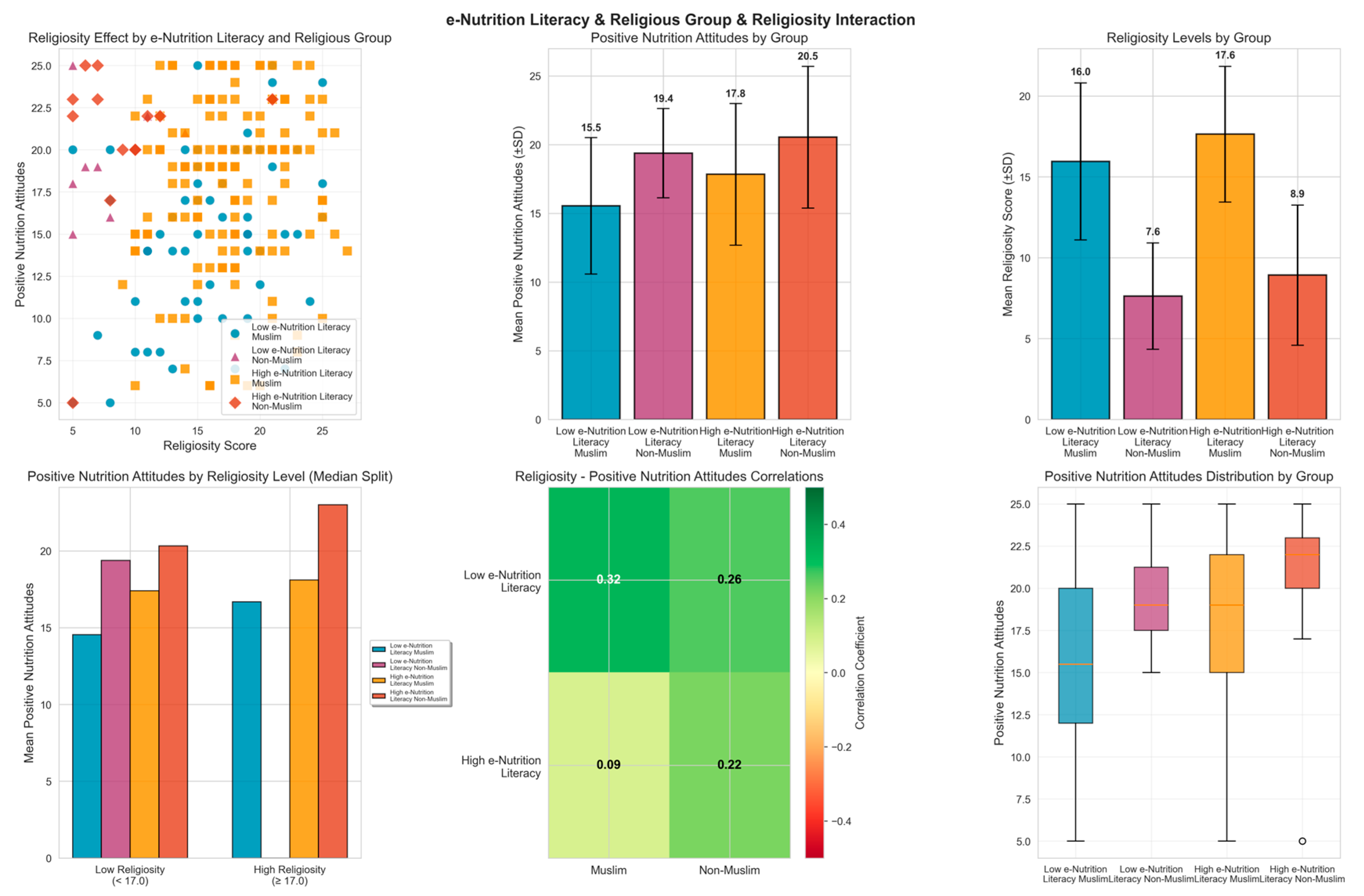

Panel A (top-left scatter plot) illustrates the relationship between religiosity scores and positive nutrition attitudes across four subgroups (Muslims with low e-nutrition literacy: blue circles; non-Muslims with low e-nutrition literacy: purple triangles; Muslims with high e-nutrition literacy: orange squares; non-Muslims with high e-nutrition literacy: red diamonds), highlighting differences in distribution between groups. Panels B and C (top-middle and top-right) present bar charts with standard deviation bars for group means of positive nutrition attitudes and religiosity, respectively, showing that the Muslim group with low e-nutrition literacy had the lowest mean positive nutrition attitudes (15.5 ± 4.96), whereas the non-Muslim group with high e-nutrition literacy exhibited the highest values (20.5 ± 5.16). Panel D (bottom-left) compares subgroup means of positive nutrition attitudes using a binary classification of religiosity based on the median value (17.0), revealing that groups with higher religiosity generally demonstrated more favorable nutrition attitudes. Panel E (bottom-middle) visualizes correlation coefficients between religiosity and positive nutrition attitudes in a color-coded heatmap, indicating the strongest correlation in the Muslim group with low e-nutrition literacy (r = 0.32) and the weakest in the Muslim group with high e-nutrition literacy (r = 0.09). Finally, Panel F (bottom-right) displays the distribution of positive nutrition attitudes within each subgroup using box plots, illustrating median values, interquartile ranges, and outliers, thereby highlighting differences in within-group variability (

Figure 5).

3.5. GLM Interaction Analysis

Based on the identified threshold, participants were stratified into low and high e-nutrition literacy groups using the cut-off score of 26.1. A Generalized Linear Model examined the interactions of religious affiliation (Muslim vs. Non-Muslim) and religiosity with positive nutrition attitudes (

Figure 5,

Table 1).

Using the cut-off score of 26.1 for e-nutrition literacy, identified as the threshold for achieving positive nutrition, participants were classified into low and high e-nutrition literacy groups. Within this framework, the interactions of religious affiliation (Muslim vs. non-Muslim) and religiosity levels were examined with respect to the dependent variable of positive nutrition attitudes. The GLM results indicated that e-nutrition literacy had a strong and borderline significant main effect on positive nutrition attitudes (β = 5.588,

p = 0.050), suggesting that individuals with high e-nutrition literacy scored on average 5.59 points higher in positive nutrition attitudes compared to those with lower levels. Similarly, religiosity showed a statistically significant and consistent effect (β = 0.332,

p = 0.010), indicating that each one-point increase in religiosity score was associated with a 0.33-point improvement in positive nutrition attitudes. However, the interactions between e-nutrition literacy and religious affiliation (

p = 0.494), e-nutrition literacy and religiosity (

p = 0.201), religious affiliation and religiosity (

p = 0.968), as well as the three-way interaction (

p = 0.774), did not reach statistical significance (

Table 1).

Group-based comparisons showed that while Muslims with low e-nutrition literacy had a mean positive nutrition attitude score of 15.55 ± 4.96, non-Muslims at the same literacy level scored higher at 19.38 ± 3.25. In the high e-nutrition literacy group, Muslims had a mean of 17.84 ± 5.15, whereas non-Muslims scored 20.54 ± 5.16. These results indicate that the effects of e-nutrition literacy and religiosity on positive nutrition attitudes are independent rather than synergistic, with both factors contributing significantly on their own. The model explained 11.6% of the total variance (Pseudo R

2 = 0.116), and given that control variables such as age and BMI did not show significant effects (

p = 0.957 and

p = 0.176, respectively), it can be concluded that e-nutrition literacy and religious values play independent yet nearly equally important roles in shaping nutrition attitudes (

Table 1).

3.6. Summary of Key Results

In plain terms, our analyses revealed three main results. First, e-nutrition literacy was by far the strongest predictor of positive nutrition attitudes—individuals who scored above the threshold of 26 on the e-nutrition literacy scale (approximately the 33rd percentile; roughly one-third of the sample fell below this threshold) scored, on average, 5.6 points higher in positive nutrition attitudes compared to those below. Given that the scale ranges from 5 to 25, this difference represents approximately 28% of the total scale range, indicating a substantial practical effect. Second, religiosity independently contributed to more favorable nutrition attitudes: each one-point increase in religiosity was associated with a 0.33-point increase in positive nutrition attitudes, regardless of e-nutrition literacy level or religious affiliation. Third, contrary to our expectations, we found no evidence that religiosity and e-nutrition literacy work together synergistically; rather, their effects appear to be independent and additive. These results suggest that interventions aimed at improving nutrition attitudes could target e-nutrition literacy skills (particularly raising individuals above the ~26 threshold) and engage religious values separately, without needing to tailor one approach based on the other.

4. Discussion

This study shows that e-nutrition literacy is the dominant determinant of positive nutrition attitudes, with clear threshold behavior rather than a purely linear pattern. Across specifications, e-nutrition literacy was the strongest OLS predictor and concentrated nearly half of the Random Forest importance. To enhance interpretability of the Random Forest model, we employed SHAP, a method that decomposes each prediction into feature-level contributions—positive SHAP values indicate that a feature increases the predicted outcome, while negative values indicate a decrease.

SHAP analyses revealed cut-points near 26.1 and 30.0, above which the contribution of e-nutrition literacy was predominantly or entirely positive. Below the functional threshold, individuals can access nutrition information without the appraisal and application skills needed to translate it into favorable attitudes. Once the threshold is crossed, the ability to identify trustworthy sources, reject myths, and plan actions likely accelerates attitudinal gains, consistent with digital health literacy theory linking search, appraisal, and application skills to behaviorally relevant cognitions [

18,

19,

20]. In practical terms, this suggests that merely increasing exposure to nutrition information is insufficient; individuals must reach a minimum competency level before digital content yields meaningful attitudinal benefits. In online ecosystems characterized by variable quality and misinformation, this skill gradient is to be expected [

21,

22]. Religiosity may operate partly through internalised norms that shape health-related goals and self-regulation; however, the strength and direction of this influence may differ across individuals. For example, individuals with higher intrinsic religiosity (i.e., faith as an internalised commitment) may be more likely to translate value-consistent motivations into stable nutrition attitudes, whereas extrinsic religiosity (i.e., faith motivated primarily by social approval or external demands) may be less consistently related to health-oriented attitudes. In addition, socio-cultural support (e.g., family and community norms, supportive peer networks, and access to trusted health information sources within religious communities) may amplify or buffer the association between religiosity and nutrition attitudes. The heterogeneity observed in SHAP dependence plots underscores this variability, showing that the same level of religiosity can correspond to different attitudinal outcomes depending on individuals’ digital skills and contextual constraints. Consistent with this individual-level variability, the observed SHAP heterogeneity may reflect psychological and environmental moderators such as digital access and skills, exposure to nutrition misinformation, trust in professional guidance, perceived social norms, and broader socio-economic constraints. Future longitudinal and intervention studies are needed to test these moderation hypotheses directly.

Our results are broadly consistent with evidence suggesting that higher digital nutrition literacy is linked to more favorable nutrition-related attitudes and behaviors across settings. For example, population evidence from Taiwan has linked e-healthy diet literacy to health-related behaviors and outcomes [

9], supporting the relevance of this construct beyond a single cultural milieu. In Türkiye, studies have supported the reliability and validity of Turkish adaptations of the e-Healthy Diet Literacy Scale and documented meaningful associations with related literacy constructs and participant characteristics [

23]. Moreover, Turkish empirical work examining e-nutrition literacy alongside food label reading and positive nutrition attitudes has reported systematic variation across age groups, reinforcing the practical relevance of digital nutrition literacy for adult nutrition attitudes [

24]. By leveraging SHAP to visualize non-linear and threshold-like effects, the present study extends this literature by revealing how digital nutrition literacy may function less as a gradual continuum and more as a foundational prerequisite skill that enables other motivational factors to exert influence. Within a majority-Muslim adult sample, our study extends this literature by jointly modeling e-nutrition literacy and religiosity in the same explanatory framework. At the same time, the threshold-like pattern suggested by SHAP should be interpreted cautiously: prior studies typically treat literacy effects as continuous gradients rather than discrete cut-points, so the cut-points observed here are best viewed as exploratory and hypothesis-generating, pending replication and external validation.

Religiosity demonstrated a consistent and independent association with positive attitudes, while neither religious affiliation nor its interactions with e-nutrition literacy or religiosity reached significance in GLMs. This pattern suggests that religiosity may operate through internalized health norms and self-regulatory practices rather than through affiliation-based social boundaries. It aligns with value-congruent health behavior models in which intrinsic religious motivation supports self-care without requiring synergistic effects with information skills [

25,

26]. Importantly, SHAP results reinforce this interpretation by showing relatively stable, modest contributions of religiosity across the distribution of e-nutrition literacy, indicating additive rather than multiplicative effects at the attitudinal level.

The lack of support for H3—that e-nutrition literacy would moderate the associations of religiosity and affiliation with nutrition attitudes—warrants further consideration. Several factors may explain this null result. First, e-nutrition literacy and religiosity may operate through distinct and parallel pathways: e-nutrition literacy likely influences attitudes through cognitive mechanisms (information appraisal, critical evaluation, and application skills), whereas religiosity may operate through value-based motivations and internalized health norms. These independent pathways would produce additive rather than synergistic effects [

27]. Second, the sample’s religious homogeneity (90.7% Muslim) may have limited statistical power to detect interaction effects involving religious affiliation; with only 103 non-Muslim participants, detecting nuanced moderating patterns was likely underpowered Third, ceiling effects may have constrained the detection of interactions: among individuals with high e-nutrition literacy, positive nutrition attitudes were already elevated (mean = 18.1), potentially leaving limited room for religiosity to exert additional moderating influence. Fourth, the threshold-based relationship between e-nutrition literacy and attitudes—rather than a continuous gradient—may have reduced the likelihood of detecting traditional multiplicative interactions. From a theoretical perspective, the independence of these predictors aligns with dual-process models suggesting that skill-based and value-based determinants of health attitudes can function autonomously [

28]. Practically, the absence of interaction effects simplifies intervention design: programs can target e-nutrition literacy and engage religious values separately, without needing to tailor literacy interventions based on religiosity levels or vice versa.

Model behavior around education warrants caution. High-school education appeared as a useful splitter in trees despite a negative linear coefficient and only small mean SHAP differences, indicating proxy partitioning of correlated characteristics, such as age, digital skills, and access. This result underscores that feature importance does not equate to causal importance in tree ensembles and that importance can partly reflect partition utility [

29]. For policy, the target should be skills rather than credentials: lift e-nutrition literacy directly.

Age exhibited a life-stage pattern: SHAP values were negative under ~25 years and then turned positive, increasing with age. The null linear coefficient in OLS likely reflects this nonlinearity. Younger adults juggle competing priorities and face higher exposure to online misinformation, which can blunt favorable attitudes unless corrected with targeted content and efficacy cues [

30]. Accordingly, age-tailored messaging that combines myth debunking with actionable guidance may be particularly important for the under-25 segment.

BMI and most sociodemographic factors had limited predictive utility. BMI showed bidirectional, weak contributions, plausibly reflecting heterogeneity in body image, weight concern, comorbidities, and prior counseling. Small, inconsistent effects are common when distal anthropometrics are linked to proximal attitudes that are more tightly governed by cognitive and behavioral skills such as information appraisal and self-efficacy [

31]. Collectively, modest R

2 and weak demographic effects indicate that a larger share of attitudinal variance likely resides in unmeasured psychosocial and environmental constructs such as norms, media diet, self-efficacy, and food environment.

From a methods standpoint, linearity tests did not reject the multiple-regression specification, yet heteroskedasticity, non-normal residuals, and influential observations were present. Robust HC1 errors mitigated inference issues, and tree models yielded only marginal out-of-sample improvement, indicating limited exploitable nonlinearity in available predictors. These diagnostics support a skills-first intervention logic: rather than searching for complex demographic interactions, move the population above the functional e-nutrition literacy threshold with micro-learning, guided practice, and simple decision aids [

19,

32,

33].

The data support two practical levers. First, set a program target to lift low-literacy individuals above ~26 and, where feasible, closer to 30, since returns appear steeper beyond these points. Second, integrate faith-respectful framing to engage intrinsic motivations associated with religiosity while keeping the curriculum focused on actionable information skills. For youth, add myth-busting modules and low-friction planning prompts.

This study has several limitations that should be taken into account when interpreting the results. This cross-sectional design precludes causal inference, and effect sizes were modest, suggesting that important psychosocial or environmental determinants were unmeasured [

19]. In addition, the sample was predominantly female (69%) and highly educated (84% with a university degree), which may have influenced the observed associations and limits the generalisability of the results to more gender-balanced or less-educated adult populations. The sample was young, university-weighted, female-skewed, and predominantly Muslim, reflecting voluntary online recruitment; generalizability is limited beyond similar populations. All constructs were self-reported, raising the possibility of common-method bias and measurement error. The proposed e-nutrition literacy thresholds are data-driven; they require prospective validation before adoption in screening or program targeting. Model diagnostics indicated heteroskedasticity, non-normal residuals, and the presence of influential observations; while robust errors and cross-validation were used, residual model dependence cannot be ruled out [

32,

33]. Finally, Positive Nutrition Attitudes were operationalized with a brief composite; richer measures of norms, self-efficacy, and media exposure would likely explain additional variance [

31]. The modest explained variance across models (R

2 ≈ 0.04–0.06) suggests that important psychosocial and environmental determinants of nutrition attitudes—such as social norms, media exposure, self-efficacy, and food environment characteristics—remain unmeasured. While this limits predictive utility, the primary aim was to identify relative predictor importance rather than maximize prediction. The proposed e-nutrition literacy thresholds (26.1 and 30.0) are entirely data-driven and exploratory; they require prospective validation in independent samples before any clinical or programmatic application.

In summary, the results indicate that e-nutrition literacy operates with a functional threshold around ~26, above which its contribution to positive nutrition attitudes becomes consistently positive. Religiosity independently supports favorable attitudes, whereas most demographic factors play a comparatively minor role. Together, these results suggest that effective interventions should prioritize strengthening actionable nutrition information skills, complemented by value-aligned messaging to enhance engagement and relevance.

Future research should prospectively validate the data-driven e-nutrition literacy thresholds identified in this study to determine their stability and predictive utility across populations and settings. Experimental or longitudinal designs are also warranted to clarify causal pathways between e-nutrition literacy and positive nutrition attitudes, and to assess whether improvements in literacy translate into sustained attitudinal or behavioral change over time. In addition, incorporating psychosocial and environmental factors—such as self-efficacy, social norms, media exposure, and food environment characteristics—may help explain additional variance and refine intervention targets. From an applied perspective, these results suggest that nutrition policies and programmes could benefit from threshold-informed screening and evaluation approaches, focusing on lifting individuals above functional e-nutrition literacy levels and assessing programme effectiveness not only by exposure but by demonstrated gains in information appraisal and application skills.

Practical implications of the present results suggest several actionable directions for nutrition practice and public health, particularly in digital information environments. First, e-nutrition literacy appears to be a modifiable skill that can be targeted through brief, structured micro-learning modules (e.g., how to verify sources, interpret nutrition claims, and differentiate evidence-based guidance from sensational content) delivered via mobile-friendly formats. Second, in settings where faith-based communities shape health norms, partnering with trusted religious networks and community institutions may help disseminate evidence-informed nutrition messages in value-congruent ways while discouraging misinformation. Third, public health and professional bodies could strengthen “infodemic” mitigation strategies by providing shareable, plain-language content, rapid myth-correction resources, and guidance for influencers/community leaders who communicate nutrition information online. Fourth, given potential disparities in digital access and skills, interventions should prioritize groups that may be at higher risk of low e-nutrition literacy (e.g., older adults, individuals with lower educational attainment, and those with limited digital access), using tailored delivery channels beyond social media when needed. Finally, in clinical and counseling contexts, brief screening of e-nutrition literacy could help identify individuals who may benefit most from targeted education and guided digital navigation support, thereby potentially improving receptivity to dietary guidance and reducing vulnerability to misleading online claims.